Introduction

Sexual health promotion can encompass any activity that promotes positive sexual health, reduces the incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV, reduces unintended pregnancies including teenage pregnancy, promotes sex and relationships education, brings about change in prejudice, stigma and discrimination, and general awareness-raising work. Many people in the UK are now taking on sexual health promotion roles and in a number of settings including home, care, community, youth, secure, school and other educational settings (SEF, 2005). The role of teachers with regard to the sexual health of young people was formally recognised by the introduction of guidelines for relationships and sexuality education (DfES, 2000; CCEA, 2001), and more recently promoting sexual health was flagged as a key activity within the primary care setting (DoH, 2003).

In recent years, sexual health has been emphasised in national, regional and local strategies as a target for health and social well-being. The UK government is committed to improving sexual health and reducing health inequalities, and recognises the direct links between sexual ill-health, poor housing, unemployment, discrimination and other forms of social exclusion. The government’s measures to improve sexual health were set out in their Strategy for Sexual Health and HIV (DoH, 2001). This national strategy for England focused on the reduction of STIs and unintended pregnancies and aimed to improve services, information and support, and reduce inequalities. The strategy acknowledged the unacceptable variations in the quality of sexual health services provided across the country and identified the need for local sexual health strategies to respond to the needs of local populations and recommended more sexual health provision in primary care.

In Northern Ireland (NI), the Teenage Pregnancy and Parenthood Strategy and Action Plan 2002–2007 (DHSSPS, 2002a) was developed, which sets a number of targets, including a reduction in the rate of births to teenage mothers and an increase in the age of first sexual intercourse. The strategy emphasised the fact that the problem could not be tackled in isolation but required a multi-agency approach of which primary care professionals formed a part.

Investing for health (DHSSPS, 2002b) moved the emphasis of health policy away from concentrating on the treatment of ill-health towards the prevention of ill-health and a holistic approach to the promotion of health and well-being of individuals and communities. Within this document, sexual health was highlighted as a key area for action and committed the DHSSPS to publish its own sexual health promotion strategy. The consultation document, Sexual Health Promotion Strategy and Action Plan (DHSSPS, 2003), aims to improve, protect and promote the sexual health and well-being of the population in NI. In particular, the strategy concentrates on reducing the incidence of STIs, reducing the number of unplanned births to teenage mothers, providing appropriate, effective and equitable sexual health information and facilitating access to sexual health services.

It is crucial to place these regional and local health strategies against a backdrop that portrays sexual health in NI as poor compared with the rest of Europe. The UK has one of the highest teenage pregnancy rates in Europe (WHO, 2001), where it is a major social and health concern. In NI, there has not been a notable increase or decrease in the rate of teenage pregnancies over the past 10 years and approximately 1400 live births were recorded in 2005 to young women less than 20 years of age (HPA, 2007a). The reported rate of STIs is increasing in NI (HPA, 2007b). Between 2001 and 2005, total diagnoses of uncomplicated chlamydial infection increased by 72% to approximately 1600 cases (HPA, 2007b).

The recent sexual health strategies have clearly placed sexual health on the agenda in primary care settings and these priorities, together with NI’s sexual health history, were central to this project. The main aim of the study was to assess the sexual health promotion activities within the primary care setting across the Northern Health and Social Services Board (NHSSB) in NI. More specifically, the study assessed the views of general practitioners (GPs) and practice nurses (PNs), identified training needs and any models of good practice relating to sexual health promotion in the primary care setting. The NHSSB is the second largest of the four boards established in NI. Just under half a million people live within the Board’s area, which covers 10 council areas.

Methodology

This study was conducted using both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. A series of semi-structured interviews with both GPs and PNs was conducted to assess the views of the health professionals on what they considered to be the key issues in relation to sexual health in primary care. These interviews also provided information to assist in the design of a questionnaire that was used to elicit information about sexual health promotion activities within primary care settings in the Board area.

Semi-structured interviews

Prior to conducting the interviews, a literature review was carried out to provide topics for discussion during the semi-structured interviews. It was considered that interviews with both GPs and PNs would not only help to identify the key issues in relation to sexual health in primary care but also highlight local issues that are unidentifiable from the literature.

The Board’s area consisted of 10 district council areas and one GP and one PN was randomly selected from each. All GPs and PNs working in the Board were eligible for selection. The selected GPs and PNs were telephoned, briefed about the study and their participation requested.

The interview schedule was structured under four separate categories: (1) demographic details; (2) sexual health policy and practice; (3) barriers to sexual health promotion; and (4) sexual health education. The semi-structured, face-to-face interviews lasted approximately half-an-hour and were tape-recorded, with the permission of participants. The tapes were subsequently transcribed verbatim and analysed manually using a content analytic approach. Members of the Research Team carried out inter-rater checks to minimise bias, thus ensuring an acceptable level of reliability was reached for the data analysis.

Questionnaire survey

A postal questionnaire survey was employed to collect data from all GPs and PNs working within the Board area. Contact details for all 255 GPs and 121 PNs were obtained from the Board’s Family Practitioner Unit. Information from the literature review and themes identified from the semi-structured interviews were used to inform the questionnaire design.

At the initial stage of the questionnaire design, the instrument was forwarded to the Research Advisory Group to check for clarity and suitability for the professional groups as well as the validity of the content. Following feedback, minor adjustments were made and the questionnaire piloted. As a result, some questions were rephrased and necessary adjustments were made to the instructions for completion. This process of development resulted in a questionnaire with content and face validity but no further validity or reliability tests were conducted.

The final questionnaire was divided into four sections. Section A included questions on sexual health policy and current practice in relation to sexual health promotional activities. Section B assessed what training participants had undertaken and what further training they considered important. Section C attempted to determine what primary care staff considered as barriers to sexual health promotion. The final section comprised questions about the use of generic education materials and materials in use to facilitate sexual health promotion. Questions in all sections contained a mixture of closed and open-ended questions. The same questionnaire was used for both the GP and PN cohort.

Those who had participated in the interview stage of the project were not asked to complete a questionnaire. Questionnaires, together with a covering letter and a prepaid envelope, were sent to 248 GPs and 111 PNs working in the Board area. All completed questionnaires were coded and descriptive statistics produced using the SPSS statistical package (Version 11; Chicago, IL, USA). No statistical testing was carried out at this stage.

Ethical approval to carry out the study was obtained from the University’s Research Ethical Committee. GPs and PNs were provided with an information sheet providing details about the study and were assured that all data provided would be confidential. All tapes were anonymised before transcription.

Results

A total of 120 GPs and 52 PNs returned the questionnaire, representing response rates of 48.4% and 47.3%, respectively. All 10 PNs who were asked to take part in a semi-structured interview agreed to participate but two GPs declined. Due to the limited time available and the situation that data saturation had been reached, only seven GP interviews were conducted. All PNs interviewed were female, whereas both male and female GPs were included. Results from both the questionnaire survey and the semi-structured interviews have been presented together and all quotes provided have been taken from the interview transcripts.

Sexual health policy and practice

Overall, health professionals interviewed were unaware of the existence of any formal practice policy for sexual health and most arrangements for sexual health management within the practices were on an informal basis. GPs who were interviewed felt the new GP contract, which came into effect just after this study was completed, would not make a substantial difference to the management of sexual health although it may encourage some to put in place formal practice protocols for dealing with specific sexual health issues.

At the minute, we do not have any formal protocols. The only real formal policy we have is that the practice nurses cannot prescribe anyone presenting with a sexual health problem but we have to refer them to the doctor.

(PN)

No formal policy as such. With new contracts coming in, we are getting some policies together on things like, eg, the morning after pill… we have not looked at all aspects of sexual health but there will be things we will be targeting with the new contract.

(GP)

The lack of any formal practice protocol for dealing with sexual health issues was accentuated when health professionals were asked in the questionnaire which health professional group within their practice spends most time dealing with sexual health issues. The questionnaire responses provided by GPs would indicate that no specific health professional had been allocated a role of sexual health lead within their practice. Almost half of the GPs (n = 55, 48.7%) felt that a female GP spent the most time on sexual health promotion; 10% (n = 12) considered it was their PN and 13.3% (n = 15) felt that the role was shared between all health professionals within the practice. Three quarters of the female GPs surveyed (n = 31, 75.6%) considered they spent more time on sexual health issues than other health professionals. However, comments made by female GPs during the interviews would suggest that this assumed role was not always because of increased training or knowledge in the area but because of the perceived role of the female GP and the choice afforded to patients.

The responsibility has come about by default as female patients request me in relation to gynae problems as I am the only female doctor in the practice.

(GP)

I see a lot of young people, as I am the youngest in the practice. A lot of young people moving into the town are registering with me so I would have a younger population than other partners. Although I have a special interest I want to maintain general skills and not get off-loaded with sexual health promotion from other partners.

(GP)

Similarly, questionnaire responses by PNs also showed that they found it difficult to identify the person principally responsible for sexual health promotion. PNs also reported that a female GP spends more time on sexual health promotion than any other health professional (n = 18, 34.6%); a quarter felt that they spend the most time on sexual health promotion (n = 13, 25.0%) and a further 21.2% (n = 11) believed the responsibility of sexual health promotion was shared equally among all health professionals.

I wouldn’t say that I have any special interest in sexual health as I have no training in the area plus I consider my role is limited in this respect.

(PN)

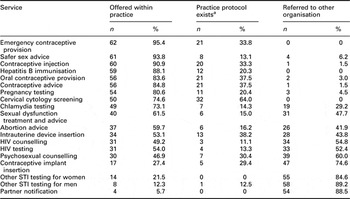

In addition to a general practice protocol for sexual health, GPs were also asked in the questionnaire whether a practice protocol existed for the specific sexual health services offered within their practice and whether clients are referred to other organisations. For this analysis, only one GP questionnaire per practice was used. At least one GP from 70 of the 82 practices returned a questionnaire.

Table 1 demonstrates that most GP practices do not have protocols for the specific sexual health services they provide; the exception being that two-thirds (64.0%) of practices offering cervical cytology screening have a protocol in place. Emergency contraception, while offered within most practices (95.4%), is provided without a practice protocol in 66.2% of cases. Although emergency contraception is offered within most practices, the interview data indicated that not all GPs in each practice provide this service, creating difficulties when certain GPs are not on duty.

Table 1 Sexual health service provision within practices

STI: sexually transmitted infection.

aPresented as the % of practices offering the service.

We can’t prescribe them so they would have to see the GP. Sometimes there isn’t a GP on duty who will prescribe it. There are three GPs here and only one will prescribe in which case they would be advised that they can buy it or they can go to Casualty and wait to be seen.

(PN)

Almost all practices offer safer-sex advice, contraceptive advice and a range of contraceptive services. More than half of the practices offer advice on abortion, although with no protocols in place it would seem that this advice was provided on a personal basis rather than following any practice policy.

This is a moral issue. I advise the patient that I am not in favour of termination for moral reasons and give them the name of another doctor in the practice who will discuss it with them … I don’t want to be judgemental but maybe when they see that I have moral objections they will reflect on it and think again.

(GP)

Apart from Chlamydia testing and HIV testing, the majority of practices refer both male and female patients to GUM clinic services for other STI testing. Partner notification was offered by very few practices and was generally regarded as the responsibility of GUM clinics. Interviews with GPs indicated their concerns with regard to the services provided by and referrals to the GUM clinics; in particular, lack of feedback about patients’ outcome and lack of information about access to GUM clinics.

We get no information back from the GUM clinic – they have to get permission from patients to send information to us.

(GP)

In contrast, some GPs considered this lack of feedback from the GUM clinic to be an advantage to the patient.

I always advise patients going to GUM clinics and tell them to say that they do not want their GP to know – because of becoming computerised there is a terrible lack of confidentiality. A one off indiscretion at an early age will now follow a patient their life time – insurance companies, etc.

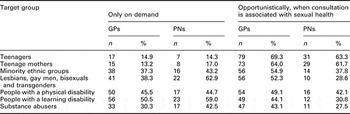

Results from the questionnaires indicated that the majority of GPs (77.2%, n = 88) and PNs (90.2%, n = 46) reported that they do not specifically target any groups ‘at risk’ of poor sexual health. Of those who did, most indicated that young sexually active females taking oral contraception would be specifically targeted for sexual health promotion. This fact was reiterated when GPs and PNs were asked in the questionnaire to indicate how they normally engage in sexual health promotion for a number of specific client groups. Teenagers and teenage mothers were the group that health professionals were most likely to engage in opportunistic health promotion as shown in Table 2.

Table 2 GPs and PNs engagement in sexual health promotion

GP: general practitioner; PN: practice nurse.

A key difference emerged between the sexual health promotion activities of GPs and PNs. Results from the questionnaires indicated that GPs were more likely to engage in sexual health promotion when the consultation was associated with sexual health, whereas PNs tended to discuss sexual health only when requested to do so (Table 2). This was particularly evident when health professionals were dealing with lesbians, gay men, bisexuals and transgenders (LGBTs); the majority of PNs would avoid the subject unless specifically asked. Both GPs and PNs engage in more opportunistic sexual health promotion with substance abusers during a consultation unrelated to sexual health than with any other ‘at-risk’ group. One PN illustrated her sexual health promotion activities by the following quotation provided during her interview.

We only give information when it is asked for and that tends to be in visits specifically related to sexual health, for example, someone attending for a smear test may raise the issue but it is generally not mentioned or raised in any other cases unless the consultation is related to sexual health. I don’t know if the GPs ever raise the issue but I don’t.

(PN)

The majority of GPs (85.5%, n = 94) and PNs (85.4%, n = 41) reported in the questionnaire that their practice did not provide any sexual health promotion activity that they would recommend to other practices. However, interviews with GPs and PNs indicated that some felt their practice provided activities that other practices could benefit from. One GP felt it commendable that their practice had a nurse available all day for sexual health discussions, whereas another considered that their protocol for emergency contraception should be recommended to other practices. Efforts to advertise their sexual health services by using appropriate posters and videos were also felt to be good practice as was forming formal links with external agencies.

I don’t know that we are doing anything particularly well. We don’t have any services that we would recommend to others. It would be fairly basic what we offer and it is very patchy so it just clarifies we need to set up a policy as to what to do.

(GP)

Training

The health professionals were asked in the questionnaire whether they had attended any educational activities in the previous three years to increase their knowledge and skills concerning sexual health promotion. Almost 60% of GPs (59.6%, n = 68) and over half the PNs (52.9%, n = 27) reported receiving no recent sexual health training although 70.8% of GPs (n = 80) and 86.3% of PNs (n = 44) reported that they would like the opportunity to undertake further training. Reasons for not attending included lack of time due to constraints of a heavy workload, other courses taking precedence, lack of awareness of available courses and courses being scheduled at unsuitable times.

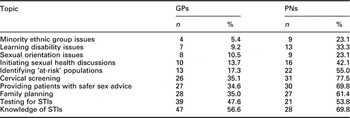

Table 3 indicates that GPs were more likely to prioritise training to increase their knowledge of and ability to test for STIs over other sexual health issues. Only a few GPs and PNs considered training in sexual orientation issues, learning disability issues or minority ethnic groups as important, even though this study has indicated their lack of sexual health promotion activity with these ‘at-risk’ groups.

Table 3 GPs and PNs indication of the importance of receiving training in specific areas of sexual health

GP: general practitioner; PN: practice nurse; STI: sexually transmitted infection.

Barriers to sexual health promotion

Table 4 indicates the issues considered to be major barriers to promoting sexual health by the health professionals who completed the questionnaire. Both GPs and PNs felt that one of the main barriers to sexual health promotion was ‘not enough time’ and this was also highlighted during the interviews.

Table 4 Potential barriers to sexual health promotion

GP: general practitioner; PN: practice nurse.

Girl in for pill and running a bit behind – quick blood pressure, run off prescription and off she goes. If I had more time I would sit down and ask her other things – time is probably the biggest barrier but you will never cure that one.

(GP)

I think time is the big thing… having protected time to do that … I don’t think we are geared enough as a practice, we don’t actually run a clinic for sexual health, so its getting the protected time in all the other clinics to do these things.

(PN)

The main barrier preventing PNs from initiating sexual health promotion was their perceived lack of knowledge/training, a barrier that was also ranked highly by GPs. While previous results indicated the health professionals desire to undergo more training in sexual health issues, most acknowledged the reality of the situation within primary care and the lack of resources that would make additional training a viable option.

Personally for me the biggest barrier is training and lack of knowledge. I would like to provide a better service but I don’t have the training which costs money both for my replacement and the course itself.

(PN)

I have had a man in with a male partner and its not something I know enough about. That would worry me that I haven’t enough education to deal with it. I might be the first person they have asked and I would feel bad if I couldn’t help them.

(PN)

Both GP and PN respondents identified other issues that could potentially obstruct sexual health promotion activities in primary care (Table 4). Getting high-risk groups to attend was seen as a major problem, although only a few of these practices had tried methods to improve attendance. GPs and PNs found it easier to discuss sexual health issues with patients of the same sex and of a similar age, although these findings were more pronounced in the PN cohort.

We are not seeing the people who need it the most – we are seeing those who are responsible.

(GP)

Yes it is a problem for some communities, for example, the gay community. They are not coming in here for protection or advice. I don’t know where they go but I know they are out there and don’t come in here.

(PN)

Issues relating to sexuality and language/ethnicity were also reported, as barriers to sexual health promotion by both GPs and PNs and their lack of opportunistic health promotion with LGBTs and minority ethnic groups would concur with these findings.

Over half the PNs considered cultural issues to be a barrier to promoting sexual health. GPs were less likely to hold this view although some still held the opinion that cultural issues presented a problem. In fact, within this Board area, cultural/religious concerns, together with issues relating to a small community and health professionals’ knowledge of the patient outside surgery were all confounding factors inhibiting sexual health promotion within the primary care setting. These issues were also highlighted during interviews with both GPs and PNs.

Some of the practices in this area have moral issues around sexual health and that can be a problem with the services they offer.

(GP)

This is a slightly rural practice and I think it is a barrier. I think people would tend to be more open in inner cities than the likes of here in discussing sexual matters again it is a cultural thing in which sex is a taboo subject and many people think it should not be talked about.

(PN)

Sexual health education materials

The final section of the questionnaire was designed to elicit information about the use of sexual health education material and whether clients were made aware of the sexual health services available. Leaving leaflets on display for open access was the most commonly used method of distributing educational and advertising materials, thus leaving the decision to obtain information entirely up to the individual clients. PNs were more likely to distribute leaflets during a consultation (67.3%, n = 33) than GPs (58.7%, n = 64).

While practices made use of generic educational materials such as leaflets and posters, many of those interviewed were unsure who was responsible for these educational materials and indeed many were unaware of their content.

Well we leave that to the receptionist or nurse if anything is needed or if we were running out. No-one specific checks up on the availability of leaflets or their content.

(GP)

I specify which ones I want and they are available on the counter at reception or I give them out. People would physically have to ask for them at reception which I suppose could be a barrier.

(PN)

Although many of the practices had the use of television and videos in their waiting room, few made use of this facility to promote sexual health or even to advertise their sexual health services. In many cases, the cultural issues associated with sexual health prevented open access to such material.

Well we have a TV and video but you wouldn’t put on anything that was in great detail. Most of the health promotion videos cover everything else but sexual health. There are obviously people who would be offended if you put on certain videos so you have to be careful that way too.

(PN)

Discussion

The overall aim of this study was to assess the sexual health promotion activities of primary care staff and was conducted using both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. Although it is becoming more and more difficult to encourage GPs and other health professionals to participate in surveys (Templeton et al., Reference Templeton, Deehan, Taylor, Drummond and Strang1997), it still remains an important tool for assessing these populations. In this study, questionnaires were used to gain information from the whole population of GPs and PNs across the Board area and a very acceptable response rate of almost 50% was achieved from both cohorts. Historically, it has proved very difficult to engage with these professional groups in questionnaire surveys and thus a number of steps were taken to encourage responses from the health professionals; PNs and GPs from across the Board area formed part of the research team; the local Primary Care Nurse Facilitator endorsed the letter accompanying the PN questionnaire and a letter signed by the Board’s Medical Advisor encouraged GPs to complete their questionnaire. Despite these strategies, 50% of GPs and PNs did not respond and this is a limitation of this study. It could be argued that the response rate achieved is a reflection of the importance placed on the topic of sexual health promotion within primary care although it must also be acknowledged that those who took part in the study were probably more interested in sexual health issues than non-participants. Another limitation of this study is that no other data were collected to ensure that the self-reports of GPs and PNs reflected reliably what took place in practice.

The World Health Organization defines sexual health as ‘a state of physical, emotional, mental and sexual well-being related to sexuality’ (WHO, 2004: 3). This broad definition clearly links sexual health with physical and mental health and given this link health professionals are increasingly recognising the importance of sexual health promotion in primary care (Sadovsky and Nusbaum, Reference Sadovsky and Nusbaum2006). Health professionals within primary care are often the first contact people have with the healthcare system and potentially these contacts offer the opportunity to promote or discuss sexual health issues alongside other problems with high morbidity and mortality. In fact, primary care services are seen as ideally placed to manage the sexual health of the population, and indeed, promoting sexual health is now seen as a key activity within primary care. However, the reality of promoting sexual health in primary care settings is ad hoc and often does not target the ‘at-risk’ population as the results of this study have demonstrated.

Sexual health is often seen as a topic that GPs and other health professionals have difficulty discussing with their patients. Similar to other findings (Stein and Bonuck, Reference Stein and Bonuck2001; Hinchliff et al., Reference Hinchliff, Gott and Galena2005), this study found a high percentage of GPs tend to discuss sexual health issues with lesbians and gay patients only when specifically asked by their clients. Hinchliff et al. (Reference Hinchliff, Gott and Galena2005) reported that GPs were not equipped to deal with the sexual health needs of their gay and lesbian patients. This was due to a lack of awareness of non-heterosexual lifestyles and sexual practices and an identified lack of training in the area. In this study, sexual orientation issues were not considered by GPs or PNs to be an important area for additional training, even though sexual health promotion was rarely targeted at this client group.

Results from this study indicated that sexual health was most likely to be discussed with people with learning disabilities only if specifically requested. Adequate education is considered ‘the key to dealing sensitively with the sexuality of clients with learning disabilities’ (Savarimuthu and Bunnell, Reference Savarimuthu and Bunnell2003) and yet very few of these health professionals felt it was an important area for further training. The results of this study would thus suggest that primary care health professionals such as GPs and PNs are not ideally placed or adequately trained to support clients with learning disability to express their sexuality.

While the questionnaire results from this study indicated that GPs and PNs were most likely to engage in opportunistic sexual health promotion with teenagers and teenage mothers, this study did not specifically assess sexual health promotional activities with young men or young fathers. In general, young men are least likely to access primary care services (Perry and Thurston, Reference Perry and Thurston2007), particularly in relation to sexual health and thus more research is needed to explore how sexual health promotion in primary care can target this understudied and underserved population.

The government’s strategy to increase the role of primary care in sexual health management, coupled with the new GP contract, altering how some GP practices deliver sexual health provision, would suggest that additional training to improve the skills and knowledge of both GPs and PNs would be vital. The results from this study provide evidence that primary care health professionals feel inadequately trained to engage in effective sexual health promotion activities with specific clients and to provide enhanced sexual health services. There are a number of gaps in generic sexual health training at both undergraduate and postgraduate level, leaving many health professionals inexperienced in dealing with the complex and sensitive issues in this area (Adler, Reference Adler1998; DHSSPS, 2003). The RCN recognises that some doctors may expect nurses to undertake additional sexual health services that they are not trained in (RCN, 2004), and emphasises that nurses should not extend their role without the appropriate training. In fact the RCN (2004) recommends that ‘all nurses working in primary care should attend a competency-based programme, such as a sexual health skills distance learning course’. In addition, Jolley (Reference Jolley2001), following a study to investigate knowledge and activities of gynaecology nurses, recommended that the preregistration curriculum should include sexual health and all nurses should ‘understand the importance of individual sexuality and are able to take a full sexual history’.

Providing a more holistic and effective sexual health service within primary care may be part of the national strategy for sexual health and the new GP contract should apparently reward such services provided in GP surgeries but barriers to an effective sexual health service within primary care still remain. In this study, GPs and PNs identified lack of knowledge, lack of time and personal embarrassment among the long list of factors. Other questionnaire surveys of both GPs and PNs have identified similar barriers (Stokes and Mears, Reference Stokes and Mears2000; Humphrey and Nazareth, Reference Humphrey and Nazareth2001; Gott et al., Reference Gott, Galena, Hinchliff and Elford2004).

A study of GPs and PNs in the North of England, not only identified barriers to sexual health management in primary care but also discussed strategies to help overcome the perceived barriers (Gott et al., Reference Gott, Galena, Hinchliff and Elford2004). While lack of skills and awareness training for health professionals was identified, Gott et al. (Reference Gott, Galena, Hinchliff and Elford2004) felt that some health professionals also had to challenge their own beliefs and attitudes before talking about sexual issues with particular patient groups. While this study did not specifically explore the beliefs and attitudes of the health professionals, it was clear from the interviews conducted that personal views did effect the provision of sexual health services, for example, the provision of emergency contraception and advice on terminations. Gott et al. (Reference Gott, Galena, Hinchliff and Elford2004) also considered that empowering patients through the provision of information was helpful in enabling patients to raise sexual health concerns during a consultation. Results from this study would indicate that the use of generic information leaflets within primary care was limited and health centre staff often controlled their distribution, limiting their value to those who actively seek information.

The cumulative effect of lack of time and lack of resources on the additional training of primary care health professionals will negate the potential for the provision of an effective sexual health service within primary care. One of the key elements of the DoH’s national strategy for sexual health is the setting up of a training plan that would equip all health professionals with the necessary skills and attitudes to deliver effective sexual health services and delivery. In NI, the consultation document for sexual health promotion acknowledges that education and training of health professionals is needed to help people work more effectively in this area (DHSSPS, 2003). Their proposed action plans include general training in sexual health skills and ‘specialised training for health and social care professionals including primary care professionals to enable them to deal effectively with sexual health issues facing lesbian, gay and bisexual men and women, and all of the other Section 75 groups’ (DHSSPS, 2003). Until health care professionals undertake such training, sexual health services and promotion will continue to be provided in a fragmented and an ad hoc basis within the primary care setting. It is not only enough to provide basic training in sexual health but also imperative that health professionals such as GPs and PNs update their own knowledge to provide successful sexual health promotion activities within their practices. Management, while acknowledging the need for specialised training, must make available the necessary resources and time to allow this to happen.

Since the research was conducted, the Board have addressed a number of issues highlighted by the study. Sexual health leaflets providing details of local sexual health services were developed and disseminated and further sexual health training and development opportunities were offered to GP practices. These initiatives may contribute to the promotion and improvement of the population’s sexual health.

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to the GPs and PNs from across the Board area, who participated in the research. The study was funded by Homefirst Community Trust.