Introduction

In 2010, the US Department of Health and Human Services issued a Disparities Action Plan to achieve a ‘a nation free of disparities in health and health care’ (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Type 2 diabetes mellitus plays a major role in health disparities because of its high prevalence and disease burden that disproportionately affect racial/ethnic minorities. In the past two decades, type 2 diabetes mellitus tripled in prevalence and now affects more than 1 in 10 US adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014; Geiss et al., Reference Geiss, Wang, Cheng, Thompson, Barker, Li, Albright and Gregg2014). Non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics/Latinos have a 60–80% higher prevalence than non-Hispanic whites, and significantly higher rates of diabetes complications including kidney and heart disease, blindness, amputations, and premature death (Lanting et al., Reference Lanting, Joung, Mackenbach, Lamberts and Bootsma2005; Spanakis and Golden, Reference Spanakis and Golden2013). Modifiable environmental and social factors are major contributors to these disparities, including socioeconomic barriers to primary prevention and equitable health care (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Strom Williams and Egede2016). Their large population health impact is expected to increase further because of the ongoing diabetes epidemic and demographic trends for Hispanics/Latinos and other minority groups, who are projected to account for half the US population by 2050 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014).

Although diabetes-related disparities have been repeatedly described (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014), evidence-based knowledge about solutions remains limited. Prior studies have suggested that generalized quality improvement (QI) directed at all patients with diabetes has largely failed to reduce disparities in diabetes control (Peek et al., Reference Peek, Cargill and Huang2007; Wilkes et al., Reference Wilkes, Bordenave, Vinci and Peek2011). We hypothesized that more intensive interventions directed at highest-risk patients will not only improve diabetes control among all racial/ethnic groups, but reduce overall disparities, because the highest-risk patients disproportionately include racial/ethnic minorities. We sought to test this hypothesis in a highly diverse patient population in a large network of community health centers. To our knowledge, this approach has not previously been tested as a strategy for reducing racial/ethnic disparities in diabetes outcomes.

Methods

We conducted a cohort study in a large network of Federally Qualified Health Centers in New York State. The Institute for Family Health (IFH), affiliated with the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, provides comprehensive primary care to a historically underserved population of ~100 000 patients in New York City and the Hudson Valley. In 2006–2008, IFH implemented an intensive intervention program directed at patients with poorly controlled diabetes (latest hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] >9%). The interventions were multifaceted and included a system-wide electronic health record (EHR)-based registry, diabetes care managers, certified diabetes educator visits, group visits in English and Spanish to promote patient education and peer support, special outreach to patients with overdue or missed clinic appointments, EHR-based clinical decision supports for diabetes care standards, and on-site HbA1c testing to enable more rapid treatment changes when warranted. Implementation of these interventions has been described previously in more detail in the context of transitioning to a Patient Centered Medical Home (Calman et al., Reference Calman, Hauser, Weiss, Waltermaurer, Molina-Ortiz, Chantarat and Bozack2013).

We examined the effects of these interventions on racial/ethnic disparities in diabetes control among all adult patients (age >18 years) with a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus at baseline (2006–2008) and at least one HbA1c measurement each year during the follow-up period (2008–2012; n=4595). Diabetes mellitus was identified based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes in the EHR (ICD-9, 250; ICD-10, E11–E14). We used Poisson regression with robust standard errors to determine prevalence ratios and 95% confidence intervals for poorly controlled diabetes (HbA1c >9%) among non-Hispanic blacks or Hispanics/Latinos relative to non-Hispanic whites at baseline and after four years of follow-up. We performed difference-in-differences analyses to examine the change in disparity in the prevalence of poorly controlled diabetes among non-Hispanic blacks or Hispanics/Latinos versus non-Hispanic whites at the end of follow-up relative to baseline. All analyses were adjusted for age, sex, and type of health insurance (Medicaid, Medicare, private insurance, or uninsured).

In secondary analyses, we examined potential interactions between race/ethnicity and age, sex, or type of health insurance in relation to poorly controlled diabetes or the change in disparities in this outcome, using likelihood ratio tests. All statistical tests were two-sided and used an α-level of 0.05. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 14.1. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute for Family Health (#2241).

Results

In this cohort of 4595 patients with diabetes, 37.0% were Hispanic/Latino, 27.9% were non-Hispanic black, 23.9% were non-Hispanic white, 7.3% were other races, and 3.9% had missing race and ethnicity information. We focused on the three largest racial/ethnic groups (Hispanics/Latinos, non-Hispanic blacks, and non-Hispanic whites) because other groups had insufficient numbers for well-powered analyses. Nearly half (45.8%) of this cohort was enrolled in Medicaid. Other patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of patients with diabetes, 2008–2012 (n=4595)

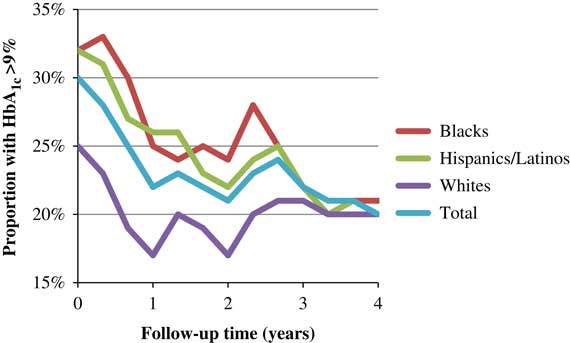

During four years of follow-up, the prevalence of poorly controlled diabetes (HbA1c >9%) not only declined in each of these racial/ethnic groups, but racial/ethnic disparities in this outcome were substantially reduced (Figure 1). At baseline, a higher percentage of either non-Hispanic blacks (32%) or Hispanics/Latinos (32%) had poorly controlled diabetes than non-Hispanic whites (25%) (prevalence ratio for each, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.14–1.43; P<0.001). After 4 years, this percentage was significantly reduced in all groups (non-Hispanic blacks, 21%; Hispanics/Latinos, 20%; non-Hispanic whites, 20%; P<0.001 for each relative to baseline). In addition, racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of poorly controlled diabetes were significantly reduced or eliminated (change in disparity relative to non-Hispanic whites: non-Hispanic blacks, P=0.03; Hispanics/Latinos, P=0.008). Figure 1 shows the change in this outcome across the study period, stratified by race/ethnicity.

Figure 1 Percentage of patients with diabetes who had HbA1c >9% during 2008–2012, stratified by race/ethnicity.

In secondary analyses, we found no significant interactions between race/ethnicity and age, sex, or health insurance type in relation to poorly controlled diabetes or disparities in this outcome (P>0.05 for each interaction). Among patients who were not included in the analyses because of insufficient follow-up (n=1228), HbA1c level did not vary significantly among racial/ethnic groups (P=0.27, Kruskal–Wallis test), thus there was no evidence that HbA1c differences among these patients accounted for the observed reduction in disparities.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to test whether more intensive clinical interventions directed at patients with poorly controlled diabetes can effectively reduce racial/ethnic disparities. In a highly diverse population, we found that this approach not only improved diabetes control in all racial/ethnic groups, but eliminated racial/ethnic disparities in this outcome. Additional follow-up will be needed to examine long-term sustainability of these effects and whether disparities in other outcomes including diabetes complications are also reduced.

Most studies of interventions to address diabetes-related disparities have focused on generalized QI in diabetes care, under the premise that ‘a rising tide floats all boats’ (Peek et al., Reference Peek, Cargill and Huang2007). Such studies have frequently reported overall improvements in diabetes care processes (eg, HbA1c test frequency) but mixed results for diabetes control (HbA1c levels), and have seldom examined other diabetes outcomes (Peek et al., Reference Peek, Cargill and Huang2007; Wilkes et al., Reference Wilkes, Bordenave, Vinci and Peek2011). Remarkably, few studies have included a comparison group of non-Hispanic whites to enable direct testing of changes in racial/ethnic disparities, and the few that have done so have found that QI interventions had no effect on disparities in diabetes control. Even when diabetes control improved among different racial/ethnic groups, racial/ethnic disparities persisted unchanged (Peek et al., Reference Peek, Cargill and Huang2007; Sequist et al., Reference Sequist, Adams, Zhang, Ross-Degnan and Ayanian2006).

Although QI interventions play an important role in improving overall care, new strategies are clearly needed for reducing diabetes-related disparities. The present study examined more intensive interventions directed at patients with the poorest prognosis based on disease control. This ‘risk-based affirmative health care action’ approach essentially weights the allocation of clinical resources toward any racial/ethnic groups that are disproportionately represented among the highest-risk patients. This strategy has the potential not only to improve diabetes outcomes among all patients irrespective of race/ethnicity, but simultaneously to reduce racial/ethnic disparities.

The present study has several strengths, including a racially diverse cohort of patients with diabetes that was sufficiently large to examine disparities with high statistical power. Our analyses included not only racial/ethnic minorities but non-Hispanic whites as a comparison group to enable direct testing of changes in disparities in diabetes control. We examined a multifaceted intervention program that targeted patients, providers, and the health delivery system, which is likely to be more effective than those targeting only one of these domains (Peek et al., Reference Peek, Cargill and Huang2007).

Certain limitations should also be acknowledged. First, this study examined a multifaceted intervention program as a whole, rather than the effects of different interventions separately. Mediation analyses in future studies may be useful to delineate which intervention components are most effective at reducing racial/ethnic disparities. The present study also focused on only one outcome, racial/ethnic disparities in HbA1c control, which was assessed during four years of follow-up. Longer follow-up will be needed to examine effects on disparities in other diabetes outcomes that take longer to manifest, such as cardiovascular and renal complications. In addition, this study included a historically underserved patient population that has a high overall prevalence and severity of diabetes and comorbidities. Additional studies will be needed to replicate this approach and assess its generalizability in other health-care settings and populations.

The immense societal costs of health disparities are well-documented, including higher health care expenditures, total disease burden, and premature mortality (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Reducing disparities is important not only for social justice, but would benefit everyone by enhancing the overall quality of health-care delivery, lowering costs, and improving population health (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Prior efforts to reduce diabetes-related disparities through generalized QI have had limited success. In a highly diverse, historically underserved population, we found for the first time that a risk-based intervention strategy effectively reduced racial/ethnic disparities in diabetes control. This approach warrants further replication and testing in other settings, which may help advance our knowledge beyond describing disparities toward developing more effective and scalable solutions.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guidelines on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.