Introduction

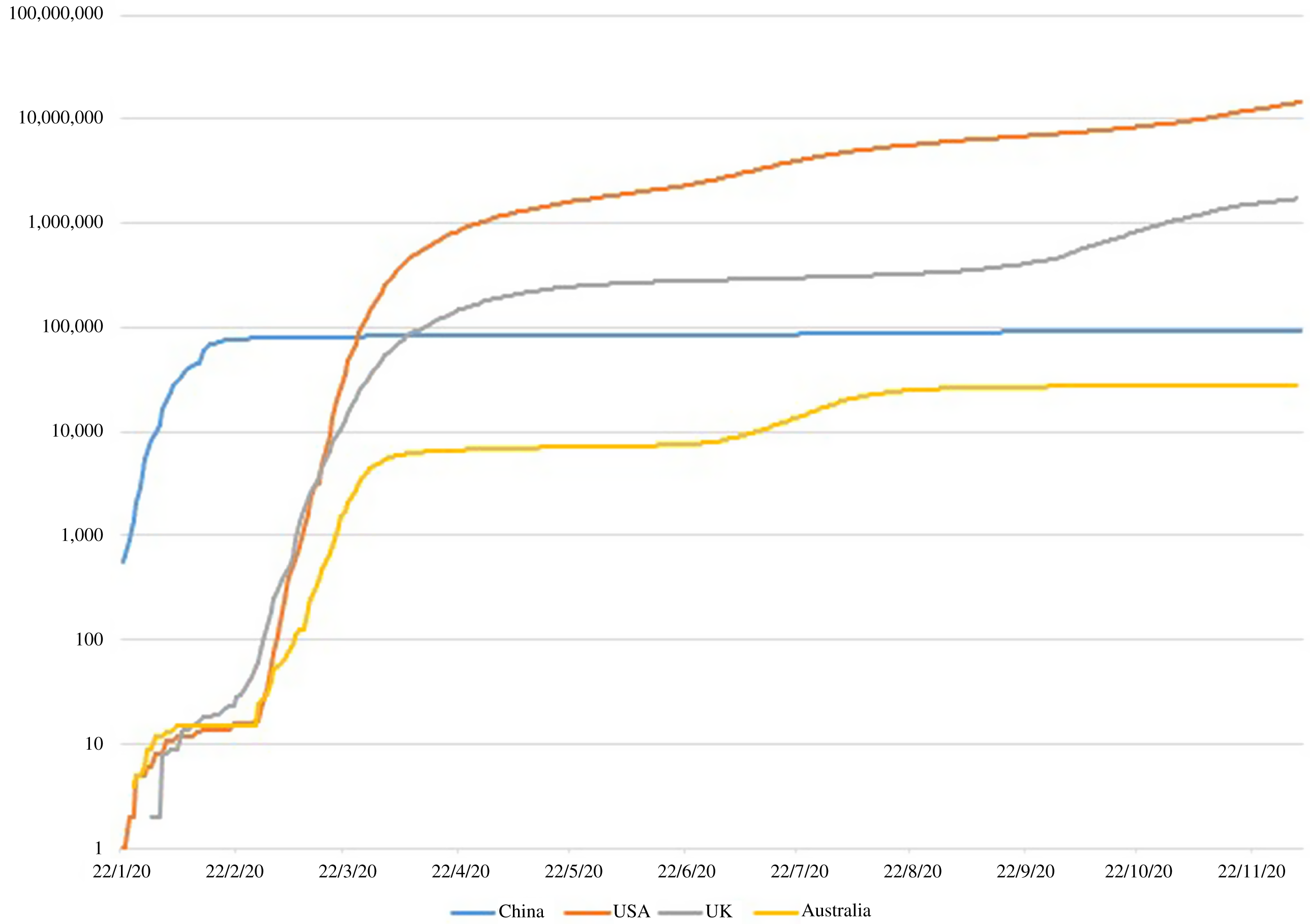

In December 2019, a new type of pneumonia – later named as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the WHO – was identified in Wuhan (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Horby, Hayden and Cao2020). In the face of this unprecedented public health crisis, China rolled out strict non-pharmacological interventions, including the lockdown of the epicentre Wuhan and subsequently its surrounding cities in Hubei province since late January 2020, when the reported cumulated number of confirmed COVID-19 cases surpassed 9,000 (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Wu, Li, Zhang, McGoogan, Li, Dong, Ren, Feng, Qi, Xi, Cui, Tan, Shi, Wu, Xu, Wang, Ma, Suu, Feng and Gao2020). The spread of the coronavirus in China began to plateau around mid-February (Figure 1). Since late March, daily new cases had been negligible and the lockdown measures were gradually relaxed until the Omicron variant hit China.

Figure 1. Cumulated number of confirmed COVID-19 cases (logarithmic scale), China and selected countries

Data source: COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at John Hopkins University

Notably, China’s response to the pandemic is characterised by strict community management. Communities were divided into smaller geographic clusters named ‘grids’ to minimise cross-grid population movements and facilitate rapid contact tracing. Each grid was placed under close surveillance and management of designated government officials, community workers, primary care workers and volunteers (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Ye, Cui and Wei2020). Despite some knowledge of China’s overall approach in controlling the spread of the infections (Zhang C. et al., Reference Zhang, Cao, Wang and Wu2020; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Wu, Li, Zhang, McGoogan, Li, Dong, Ren, Feng, Qi, Xi, Cui, Tan, Shi, Wu, Xu, Wang, Ma, Suu, Feng and Gao2020; Zhang P. & Gao, Reference Zhang and Gao2021), our understanding of the specific roles of primary care in response to COVID-19 is still limited. This study aims to fill this important gap by providing: (1) a descriptive account of how primary care responded and worked with other main stakeholders at the grassroots level during China’s fight against COVID-19; and (2) reflections on the limitations of China’s primary care and their implications in the COVID-19 context.

Methods

A retrospective, reflective approach was taken using data available to one of the authors who led China’s national community response to COVID-19. The co-author has decades of work experience in China’s primary care settings and led the National Health Commission’s expert team for community prevention and control of COVID-19, first in Wuhan (Hubei), and later in multiple cities in ten provinces/municipalities across the country, including Beijing, Kashgar (Xinjiang), Tianjin, Chengdu (Sichuan), Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Dongguan (Guangdong), Ruili (Yunnan), Yingkou (Liaoning), Xiamen, Putian (Fujian), Nanjing, Yangzhou (Jiangsu) and Shijiazhuang (Hebei). The precious first-hand experience enabled us to discuss the topic in depth from a national perspective. In preparing for writing this paper, the co-author looked back training materials (for both primary care providers and relevant stakeholders) and other documents used during their work. It was further supplemented by data extracted from relevant policy documents and academic literature, which provided contextual information and further details to validate the findings through triangulation.

A brief overview of China’s primary care network and functions

In China, primary care services are dominated by public community health institutions: township health centres and village health stations for rural and community health centres and outreach stations for urban (Figure 2). These facilities were established through top-down planning to ensure universal coverage and avoid duplications. Each rural township has one township health centre servicing on average 20 000 populations, supplemented by one health station for each village with approximately 1,000 residents (Figure 2). Due to higher population density in urban areas, each community health centre covers a neighbourhood (administratively called ‘street’) with 30 000 to 100 000 residents (General Office of the State Council, 2020).

Figure 2. China’s primary care network

Note: The average population given in brackets are estimated by dividing the total population by the corresponding administrative units number. We assume that the streets are urban, and townships are rural. All data in this figure are from 2018, collected from the National Bureau of Statistics, 2019).

Compared to their counterparts in many other countries, Chinese primary care facilities have a relatively comprehensive range of functions, including essential public health services, medical care for common diseases, prescription and dispense of medicines, and rehabilitation care for certain conditions (Table 1). Reporting of and emergence response to infectious diseases also falls within the responsibility of primary care facilities, as one of the twelve categories of essential public health services (Table 1).

Roles of primary care

Key responsibilities at the peak of the pandemic

At the national level, an overall framework for primary care under the COVID-19 outbreak was set out by the government through a series of central instructions issued in January 2020 (Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council, 2020a, 2020b; National Health Commission, 2020a, 2020b). Specifically, primary care facilities are supposed to shoulder the responsibilities including screening and triage, medical observations of quarantined people, follow-up care for hospital discharged patients, and health education (Table 2).

Table 2. Roles of primary care in response to COVID-19

Continuation of essential medical care is important during the outbreak of COVID-19. Although patients with fever were advised to go to designated hospitals directly, those in need of basic medical services were encouraged to visit community facilities to ease the loads of hospitals. Overall, primary care facilities experienced a significant decrease in outpatient visits: a drop of 25% between January and April 2020 compared with the same period in 2019 (National Health Commission, 2020c). On the demand side, many patients postponed their non-urgent visits out of fear of contacts with infectious patients in medical facilities. On the supply side, primary care providers were encouraged to provide repeated prescriptions for patients with well-controlled chronic conditions (Chinese Thoracic Society et al., 2020; Zhang D. et al., Reference Zhang, Yao, Wang, Ye, Chen, Guo, Zou, Lin, Lu, Huang, Zheng, Chi and Zhong2020). Meanwhile, telehealth consultations and health surveillance were increasingly adopted by health care providers (Liu, Reference Liu2020).

COVID-19 screening became an integral part of medical care services. All patients visiting primary care facilities were subject to the screening. The patients who purchased antipyretic, antibiotics, or common cold medicines from primary care facilities or community pharmacies were registered and were later on followed up by primary care workers through phone calls. All suspected cases were referred to designated hospitals and admitted upon confirmation of the diagnosis.

In practice, the fulfilment of these functions varied across localities due to unbalanced distributions of COVID-19 cases in China (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Lu, Yuan, Xu, Jia and Christakis2020). Different implementation models were developed, which were often constrained by the community resources available (Qin et al., Reference Qin, Huang, He, Zhang, Luo and Tang2021). However, there was a consensus among the primary care workers that their roles in reporting and referral of suspected cases, health education, and follow-up care for hospital discharged patients were fundamental in China’s battle against COVID-19 (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Li, Li, Yang, Ni, Lin, Wang, Xu and Song2021).

Working with other major stakeholders in local communities

A central leading group for COVID-19 prevention and control was established at the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in China as the top decision-making body. Local governments quickly followed suit by duplicating the central command structure staffed by local leaders and experts (He, Shi, & Liu, Reference He, Shi and Liu2020). Through this command chain, central policies were followed and implemented. The local level of emergency response was determined by the local leading groups in line with the prevalence of COVID-19. The local leading groups were authorised to coordinate efforts from different governmental agencies and stakeholders to facilitate contact tracing and information sharing (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Coordination of contact tracing in Beijing

Note: The district-level community health services management centre is responsible for supervising primary care facilities. It reports to the district-level health bureau. Prevention and control groups are set at all administrative levels, from the central level down to the county, street (or township) and community levels. They are responsible for leading and coordinating efforts in relation to the prevention and control of COVID-19.

Figure 4. Coordination of community activities in response to COVID-19

At the grassroot level, primary care workers worked closely with other major stakeholders, whether in the community-wide screening or more targeted services for those in quarantine and isolation (Figure 4). Although the community workers and volunteers mainly focused on traffic control, transportation arrangements, and supply of necessities, they received health advice from the primary care workers in relation to these activities. They also assisted with daily body temperature surveillance, contact tracing and environmental disinfection.

Primary care in a ‘COVID-normal’ phase

China managed to bring the spread of COVID-19 under control fairly quickly and transitioned to a ‘COVID-normal’ phase with either no community transmissions or confined sporadic outbreaks. In June 2020, the central government released guidelines for health care facilities to manage the risks in a COVID-normal phase (Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council, 2020c). Primary care facilities are required to play a ‘sentinel’/surveillance role and take ‘first-contact responsibility’: reporting all patients with fever to the local health authority within 1 h, referring them to a fever clinic for further assessment and making follow-up calls until a formal diagnosis becomes available. In rural areas where township health centres typically provide inpatient services, designated quarantine wards are required to be set up for on-site medical observations.

Limitations of primary care and implications

The lack of gatekeeping, limited capacity and implications for China’s COVID-19 response

Similar to many other countries, China’s COVID-19 response was much driven by fears of overwhelming hospitals. This was particularly an issue in Wuhan because China has not established a tiered medical system – despite the comprehensive network of primary care facilities, gatekeeping is not compulsory so that patients may directly visit a specialist in tertiary hospitals without any referral (Li et al., Reference Li, Lu, Hu, Cheng, de Maeseneer, Meng, Mossialos, Xu, Yip, Zhang, Krumholz, Jiang and Hu2017). In large cities like Wuhan, many patients are used to bypassing primary care facilities and visiting tertiary hospitals for any health problem. Chinese tertiary hospitals tend to have very high volumes of outpatient visits for all kinds of diseases. Patients may experience very long waiting times for their visits. Within such a system, cross-infection can easily happen, which initially significantly exacerbated the COVID-19 infections in Wuhan. For these reasons, the key priority at the peak of the pandemic in Wuhan was to quickly establish a new tiered system in response to COVID-19. This included fangcang (makeshift) hospitals for mild to moderate cases and designated hospitals for serious cases. Critically, however, during the COVID-normal phase and in the longer term, the ‘sentinel’/surveillance role of primary care facilities will likely be still constrained by the lack of gatekeeping.

Relatedly, one key contributor to the lack of gatekeeping in China has been the weak capacity of primary care. Unlike in many other countries, in China, the distinction between primary care facilities and hospitals is more in capacity (in terms of space, equipment and human resources). Compared to their counterparts in hospitals, primary care doctors are typically less academically qualified, skilled and poorly paid. Establishing a general practice workforce to better separate primary care from hospitals has been a long-standing theme of China’s health care reforms, but the progress has been slow for interlocked institutional and incentive reasons. Increasing the capacity of primary care for infectious diseases thus also became a key priority for the Chinese Government, notably by building more fever clinics within primary care facilities, to separate the treatment of people with infectious diseases.

Weak integration between medical care and public health

The pandemic also highlights that more work is needed to integrate primary care and public health. Within the Chinese primary care facilities, public health and medical services are provided by different professionals, funded by different sources of income and payment mechanisms. Despite the increase in government funding for public health services, relevant positions at primary care facilities remain unattractive in terms of salary, benefits and career prospects. During the pandemic, it became evident that there was a serious shortage of public health professionals at primary care facilities and many doctors who are routinely responsible for treating diseases have limited knowledge about infectious diseases. These issues all point to the need to further integrate medical care and public health, potentially through allocating more resources for public health, reforming the current capitation-based payments for public health services to provide better incentives, and a team-based approach to facilitate multidisciplinary collaborations. Learning experiences from other countries may also be particularly fruitful (Kinder et al., Reference Kinder, Bazemore, Taylor, Mannie, Strydom, George and Goodyear-Smith2021).

Concluding remarks

China offers a rather unique experience in its response to COVID-19, characterised by strict community management to pursue a zero-COVID strategy. The surge in workforce capacity was enabled by the Chinese Government mobilising a range of stakeholders to work collaboratively. Primary care was an integral part of this massive community response and provided various functions. China’s model proved effective in quickly controlling the spread of COVID-19, but some key weaknesses of primary care have been once again exposed, notably the lack of gatekeeping, limited capacity and weak integration between medical care and public health. The applicability of China’s model to other countries may be limited due to significant differences in socio-political, economic and health care system contexts. However, within the country, case studies of where the model worked well or less well would have great educational value and would be a productive next step in considering the Chinese experience in more detail.