Background

Achieving better outcomes for a population through preventive measures remains a major healthcare goal (Ockene et al., Reference Ockene, Edgerton, Teutsch, Marion, Miller, Genevro, Loveland-Cherry, Fielding and Briss2007). Despite preventive health successes such as the reduction in cardiovascular outcomes (Mozaffarian et al., Reference Mozaffarian, Benjamin, Go, Arnett, Blaha, Cushman, Das, de Ferranti, Després, Fullerton, Howard, Huffman, Isasi, Jiménez, Judd, Kissela, Lichtman, Lisabeth, Liu, Mackey, Magid, McGuire, Mohler, Moy, Muntner, Mussolino, Nasir, Neumar, Nichol, Palaniappan, Pandey, Reeves, Rodriguez, Rosamond, Sorlie, Stein, Towfighi, Turan, Virani, Woo, Yeh and Turner2016) and the decline in vaccine-preventable infectious diseases (Roush et al., Reference Roush and Murphy2007), opportunities for improvement remain. Among the top five causes of mortality in the United States, an estimated 20–40% of deaths are potentially preventable (Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Bastian, Anderson, Collins and Jaffe2014). While preventive health encompasses a broad range of activities, settings, and providers – including employer-based programs, direct appeals through mass marketing (Elder, Reference Elder2014), public health campaigns, and legislation such as tobacco taxes (Chaloupka et al., Reference Chaloupka, Yurekli and Fong2012) – much of this important work continues to take place at the clinician’s office. The optimal means to deliver preventive health within the primary care setting continues to be debated. Key questions include what services should be offered, in what type of office visit, and by whom.

The number of recommended preventive services issued is daunting. For example, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), which issues guidelines regarding preventive health, recommends 52 services at the grade ‘A’ or ‘B’ levels (moderate to high certainty of benefit) (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2017). Other organizations such as the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the Institute of Medicine, and subspecialty societies issue their own guidelines. The primary care provider (PCP) must review these recommendations and decide what preventive services to offer.

Even if a set of preventive services is agreed upon, the optimal time to offer them is uncertain. Office visits may generally be divided into two categories: separate, stand-alone preventive health appointments (‘preventive health visits’ or ‘wellness visits’) or visits for medical conditions. Preventive health may be delivered during either type of visit. As delivering preventive services takes considerable time (Medder et al., Reference Medder, Kahn and Susman1992; Yarnall et al., Reference Yarnall, Pollak, Ostbye, Krause and Michener2003) and real-world delivery is inefficient (Kottke et al., Reference Kottke, Brekke and Solberg1993; Ruffin et al., Reference Ruffin, Gorenflo and Woodman2000; Stange et al., Reference Stange, Flocke, Goodwin, Kelly and Zyzanski2000; Cosgrove, Reference Cosgrove2012), the dedicated preventive visit is one method for PCPs to ensure adequate attention to preventive health. The overall rate of preventive visits in the United States in 2012 was 61 per 100 persons, with variability by age, gender, and state (Hing and Albert, Reference Hing and Albert2016). PCPs report being more likely to provide patients preventive medicine during wellness visits than during acute visits (Snipelisky et al., Reference Snipelisky, Carter, Sundsted and Burton2016), and increased screening rates have been associated with health maintenance visits (Ruffin et al., Reference Ruffin, Gorenflo and Woodman2000). The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services accordingly has created the Annual Wellness Visit for Medicare beneficiaries. Yet there continues to be conflicting evidence and differences of opinion regarding the efficacy of preventive health visits, with critics citing insufficient evidence for mortality outcomes and proponents arguing for other benefits (Boulware et al., Reference Boulware, Marinopoulos, Phillips, Hwang, Maynor, Merenstein, Wilson, Barnes, Bass, Powe and Daumit2007; Krogsboll et al., Reference Krogsboll, Jorgensen, Gronhoj Larsen and Gotzsche2012; Society of General Internal Medicine, 2013; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Gaster and Dugdale2014).

In addition to these decisions of what preventive services to offer and when to offer them, there are evolving concepts as to which personnel should be involved in performing preventive healthcare. Enlisting other members of the healthcare team has been proposed as a means to improve preventive health delivery. ‘Share the Care’ (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Dubé and Bodenheimer2016) and Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) models (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016) use non-PCP staff to ensure that a patient’s preventive health recommendations are met. Despite ample literature addressing challenges to PCMH implementation (Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Giannitrapani, Stockdale, Hamilton, Yano and Rubenstein2014) and role assignment within teams (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Patrick, Topolski, Aspilnall, Mouradian and Speltz2015), there has been relatively less attention paid to exploring how PCPs wish their roles to be within healthcare teams when providing preventive healthcare.

This study sought to add to the current understanding of preventive health in the office-based setting by learning more about the perspective of PCPs in making decisions about what preventive health to offer, why they might choose to address preventive health during one visit but not another, and how they see their role in healthcare teams. Although previous qualitative studies have addressed perceived barriers and facilitators to specific preventive health topics (Simmons et al., Reference Simmons, Guerra-Reyes, Meyerson, Adams and Sanders2016; Abraham et al., Reference Abraham, Lewis, Drummond, Timko and Cucciare2017), few have directly asked PCPs how they act as agents of preventive health delivery. Given the open-ended nature of our questions, we determined that a qualitative approach was optimal.

Methods

Research design

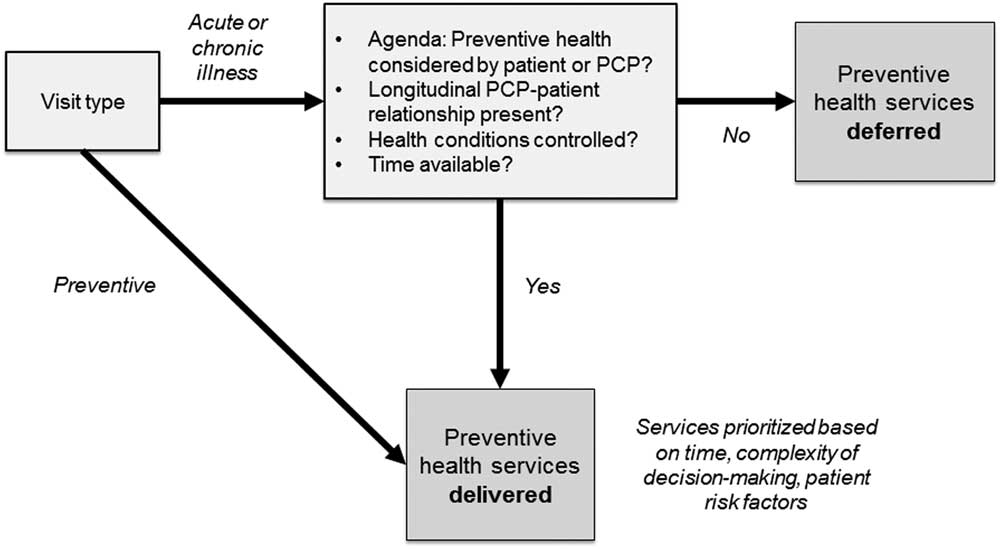

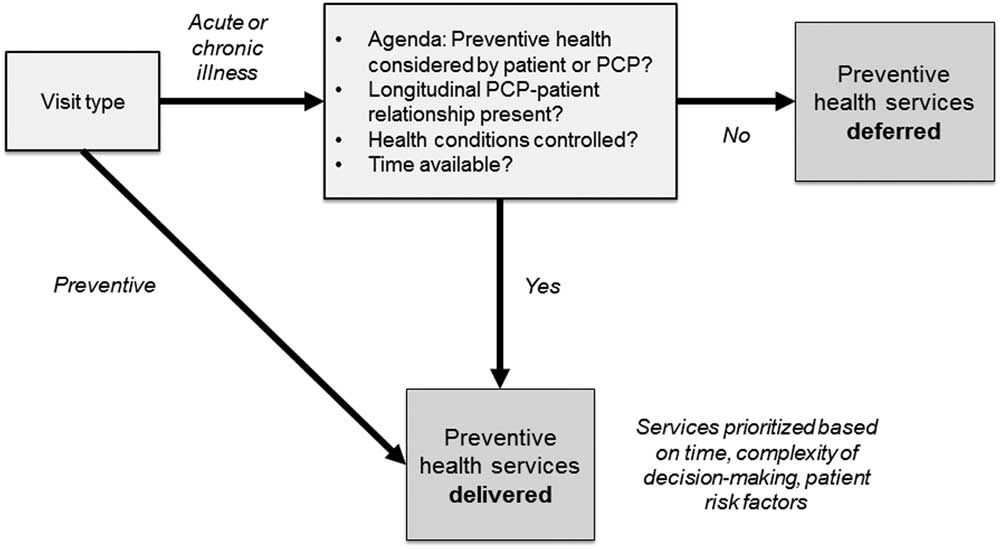

We aimed to explore the dynamics of preventive care delivery by PCPs using an approach procedurally informed by the principles of Grounded Theory (Creswell, Reference Creswell2007; Corbin and Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2015) with no theoretical assumptions. Earp and Ennett (Reference Earp and Ennett1991) point to how ‘conceptual diagrams are used to organize and synthesize knowledge, defined concepts, provide explanation for causal and associative linkages, generated hypotheses and specific research questions, plan and target interventions, designated variables to be operationalized, and anticipate analytical approaches.’ Our purpose was therefore to develop a conceptual model to help explain the decision-making process of preventive care delivery by primary care health providers.

Sample and recruitment

We defined PCPs as physicians, advanced registered nurse practitioners (ARNPs), or physician assistants who had a panel of patients for whom they were the responsible longitudinal care provider. We recruited PCPs from primary care clinics affiliated with the University of Washington, an academic medical center in Seattle, Washington, USA. These clinics were group practices in an urban setting. Subjects could work at any amount of clinical full-time equivalent (FTE). Upon receiving study approval from the Institutional Review Board, we approached primary care clinic directors to obtain permission to introduce the study at administrative meetings at those clinics and to invite PCPs to take part in the study. With the clinic director’s permission, we followed up with no more than three recruitment emails to PCPs. In total, 21 subjects from four academic clinics ultimately agreed to participate in our study.

Data collection

At the beginning of each face-to-face interview, we provided the subject with a brief overview of the study purpose, asked permission to audio-record the session, and obtained written consent. Basic demographics were gathered at the start of each session. The interview guide consisted of three topic areas related to prevention services performed during different types of visits and team-based healthcare (Table 1). The questions in the interview guide were developed based on literature review and designed to elicit answers to the research questions. Interviewers asked follow-up questions as needed for clarification and to probe for meaning. Additional questions pertained to the electronic medical record (EMR) and were not included as part of this analysis. All interviews were conducted by two of the authors between July 2015 and September 2015. Each interview session lasted ~20 min.

Table 1 Summary of key protocol questions for interviews

Data analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for content analysis of the transcripts (Creswell, Reference Creswell2007). Our analysis used the following iterative steps: (1) Three members of the research team independently read and re-read each transcript in order to achieve as broad an understanding of the content as possible. (2) Each member of the team independently conducted open coding and organized the data into subcategories. Given the sample size, all coding was done by hand. (3) All team members met face-to-face to discuss their reasons for assigning their codes, and to agree on a list of subcategories. (4) In an iterative process, a matrix was created to sort the codes into subcategories which were then grouped into clusters, out of which themes emerged.

Validation and saturation

Inter-rater reliability (Creswell, Reference Creswell2007) was reinforced by having the two physician members of the team independently code each transcript and a third qualitative research expert and non-physician code these same transcripts within a similar time for triangulation. Where there was disagreement between coders, discussion ensued until either consensus was reached or the code was discarded. Saturation was reached when no new information was forthcoming from the data.

RESULTS

Demographics

The 21 in-depth interviews included 17 physicians and four ARNPs. Subjects practiced at four different clinics affiliated with an academic medical center. These clinics included a women’s healthcare clinic, a university general internal medicine clinic, and teaching clinics at a county hospital. The average age of the primary care health providers was 48 years. In total, 71% of the participants were women and the average clinical FTE was half-time (Table 2).

Table 2 Characteristics of subjects

Theme: longitudinal care with an established PCP–patient relationship is perceived as integral to preventive care

All clinic sites in this study were group practices. Thus providers routinely saw not only their own patients but also patients assigned to other providers. When seeing another provider’s primary care patient in a clinic visit, subjects in this study strongly preferred that most preventive services be discussed between the patient and his or her own PCP, as reflected in these typical responses:

‘And for complicated preventive health … if the patient is not my primary care patient, then I usually don’t do [it]. I ask them to come back and talk with their doctor rather than I do it. Particularly for cancer screening, you need to evaluate the patient and assess whether he needs cancer screening or not.’ (Interviewee 15)

‘It’s a waste of my time to check, if a patient is not my primary patient.’ (Interviewee 6)

Subjects considered that involvement of the patient’s own PCP was essential to preventive health because of the need to understand the patient’s unique values and beliefs. They regarded that the PCP was in the best position to have this knowledge:

‘I typically don’t address preventive service if it is not my primary patient… I think it is harder to know [the] patient’s knowledge, philosophy and beliefs in that shorter conversation. I think it is harder to do that if you don’t have that relationship.’ (Interviewee 11)

‘If it’s another provider’s patient and you know they’re due for a colon cancer screening or it looks like they’ve declined multiple preventive things in the past … it seems like a conversation that they really need to have with their primary doctor…’ (Interviewee 5)

‘There’s something about the doctor-patient relationship that is better for somebody to have one doctor who knows them…’ (Interviewee 1)

This utmost respect for the longitudinal relationship drove clinicians to defer preventive health to another visit if that relationship was not present.

Theme: conflict and doubt accompany non-preventive visits

In contrast to a dedicated preventive health visit, during acute or chronic care visits providers must consider whether to address preventive health at all. We found that providers expressed a desire to accomplish some preventive health during non-preventive visits, but also felt discomfort at either falling short due to time constraints or being only able to focus on brief interventions. The following responses represent this theme:

‘But I’m not, I’ll be honest, I’m not consistent in what I do for preventive health in my non-preventive visits.’ (Interviewee 1)

‘…it’s one of those things I think I should do.’ (Interviewee 4)

In other words, providers felt that they should address preventive health in different types of non-preventive visits, but often felt that they did not or could not do so effectively.

Theme: PCPs defer preventive health for pragmatic reasons

We found that despite this conflict, PCPs nevertheless forged ahead and acted pragmatically to address more pressing concerns and often deferred preventive health to another time:

‘If you’re talking about 3 or 4 acute problems, there might be no time for anything else.’ (Interviewee 17)

‘If the patient has [an] acute problem basically I deal with that first and if I have enough time I will address preventive health during that visit.’ (Interviewee 15)

‘It is all based on time. I will have the health maintenance tab open. I do prep the night before and I write the things down to address. But if the patient comes in late, then I will skip it.’ (Interviewee 6)

‘With a patient … who has so many different problems, usually the preventive health is low priority. Or the last priority if there’s time at the end. I don’t attempt to really do more than one or two preventative interventions, and often just save it and chip away at it each visit if I can.’ (Interviewee 17)

While deference was the norm, for measures that were perceived as either low risk or relatively quick, such as immunizations, they would make exceptions:

‘So, if it’s flu season and a patient always gets a flu shot and says “Hey could I get my flu shot while I’m here?”—sure.’ (Interviewee 9)

‘The tests that are pretty easy to get, I don’t have to spend much time on, I will say “Hi, we’re going to check this, this, and this and I put those orders in.’ (Interviewee 19)

Providers who routinely conducted separate preventive visits valued the time these visits afforded to focus on prevention.

Theme: when preventive health is addressed, providers use multiple contextual factors to decide which interventions are discussed

Once the decision is made to address prevention, regardless of visit type, then providers must choose what services to address. While some providers simply reported providing a patient an entire list of what preventive health measures are ‘due’, in most cases PCPs attempted prioritization. Providers cited a number of factors, including patient preferences, the patient’s health conditions, prompts from the EMR, local quality improvement initiatives, and the perceived impact of a preventive service:

‘…I try to tailor the visit to be what the patient sort of wants and expects.’

‘I use age- and gender-based recommendations and then depending on the patient like how healthy they are or they are not.’ (Interviewee 18)

‘I individualize the guidelines depending on the overall health of the patient. If someone is extremely ill from serious multiple diseases and if the life expectancy is short then of course I will not be doing cancer screening.’ (Interviewee 16)

‘I’m also influenced some by what the quality measures are that the clinic is being graded on.’ (Interviewee 18)

For guidance, most of the providers in these clinics used the USPSTF, citing that ‘compared to other societies they are less biased’ and ‘they are the most evidence-based’. But, they also used multiple guidelines, often for topics not addressed by the USPSTF or if there were competing guidelines they felt the patient should be aware of.

Among preventive services, these providers in general prioritized cancer screening. Reasons for this included their perception of patient concerns:

‘I will say that I always, I pretty much always address cancer screening…the fear of cancer’s so huge in our society, and clearly I would not want to miss a cancer…’ (Interviewee 8)

In contrast, other screening services might be considered valuable but lower priority: ‘…missing things like a hearing problem – probably not the end of the world’. In addition, screening for depression was generally conducted less frequently because it was felt to be symptomatic if present:

‘If I know the patient, if they are my patients, if I know them for years, I probably don’t do any psychosocial screening for depression or anxiety during a preventive health visits because I know that person.’ (Interviewee 16)

‘I get into psychological screening and other issues secondarily. Usually… honestly when I think of it. I mean, but I would usually be triggered by other factors…’ (Interviewee 14)

Thus there was no single guiding principle for selecting preventive health services, but rather a mix of multiple considerations.

Theme: PCPs desired team-based preventive health delivery, but wish to maintain their role when shared decision-making is required

Nearly all providers expressed an interest that other members of the healthcare team such as nurses or medical assistants be involved in their patients’ preventive healthcare. They did not wish however to cede all preventive healthcare to other team members. The more controversial or complex the preventive health topic, the more the providers wanted to maintain primacy in discussion with the patient. For example, many providers supported a role for a medical assistant to independently address immunizations, but for cancer screening, they showed discomfort if the PCP was not involved:

‘For mammogram and colonoscopy, things are too nuanced for someone not specifically trained in it, so I would say someone being specifically trained is good.’ (Interviewee 10)

‘I think the mammogram discussion … it’s very nuanced and… the guidelines differ so much…I think I would want to have the initial discussion.’ (Interviewee 1)

‘I think for cancer screening it would be appropriate if it is addressed by a physician. For vaccines, it is okay if they [the medical assistants] are letting you know if it is pending.’ (Interviewee 19)

These providers were comfortable with a staff member checking and suggesting preventive health measures that required shared decision-making, as long as the PCP still worked directly with the patient to establish the appropriate screening measure and interval.

Discussion

This qualitative study adds to the existing literature by not only describing the barriers that PCPs face, but also presenting a model of PCPs as active decision-makers in their practice. We describe how they make decisions as to when to offer preventive services, which ones to address, and why, and how they view their role as part of a care team.

When addressing prevention, we uncovered a steadfast adherence to the longitudinal patient – PCP relationship regardless of other barriers or constraints. This modest but important distinction emerged in several contextual situations, such as when there were concerns about having limited knowledge of another PCP’s patient, and when there were concerns about conducting adequate shared decision-making. These clinics all had EMRs – the value of the longitudinal care relationship is therefore in information not always accessible in the chart, concordant with prior findings that interpersonal communication and coordination of care scale scores were associated with being more up-to-date on screening services and health habit counseling (Flocke et al., Reference Flocke, Stange and Zyaznaski1998).

Do providers place value in addressing prevention during illness visits? The issue of visit type – preventive visits versus those for acute or chronic illnesses – remains important. It may be easy to forget how much healthcare has changed – prior studies labeled the addressing of prevention during chronic care or illness visits as the ‘opportunistic method’, and in a previous era many physicians did not endorse this approach at all (Rebelsky et al., Reference Rebelsky, Sox, Dietrich, Schwab, Labaree and Brown-McKinney1996). In contrast, subjects in this study clearly valued addressing prevention, and felt that they should address it routinely. The theme of conflict and doubt arose accordingly in settings in which they felt they could not do so adequately.

Exploring the reasons for such doubt led to the theme of pragmatism. Several studies have examined delivery of preventive services during non-preventive visits with regard to how infrequently it occurs (Kottke et al., Reference Kottke, Brekke and Solberg1993; Stange et al., Reference Stange, Zyzanski, Smith, Kelly, Langa, Flocke and Jaen1998; Reference Stange, Flocke, Goodwin, Kelly and Zyzanski2000), what observed factors are associated with addressing prevention (Flocke et al., Reference Flocke, Stange and Zyaznaski1998), and what communication methods are used (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, DiCicco-Bloom, Strickland, Headley, Orzano, Levine, Scott and Crabtree2004). Most studies however did not address why providers choose to address preventive health in a given clinic visit, and what factors they perceive as being relevant. Our study explores this concept further by asking providers directly how they make decisions regarding when to address prevention in non-preventive visits. We found that PCPs consistently wrestled with prioritizing non-preventive versus preventative care during non-preventive visits. Similar to previous studies, time constraints continue to be a major factor in deciding whether to address preventive health (Burack, Reference Burack1989; Kottke et al., Reference Kottke, Brekke and Solberg1993; Cornuz et al., Reference Cornuz, Ghali, Di Carlantonio, Pecoud and Paccaud2000; Yarnall et al., Reference Yarnall, Pollak, Ostbye, Krause and Michener2003). While our subjects expressed feelings of exasperation and vexation in their desire to deliver preventive care, these providers were not overwhelmed by these constraints. Rather, their decision-making was characterized by an underlying pragmatism, grounded in the circumstances of the patient. These PCPs evaluate each clinic visit and prioritized and triaged care based on the particular or unique circumstances of the individual patient. Barriers to preventive care are realized in that the immediate circumstances of the patient may have to take priority, consequently hindering or giving less priority to preventive care. Such real-world conditions meant that these providers practiced a constant state of triage with regard to fitting in preventive health.

The decision to choose one preventive service over another is complex. For example, one could postulate that providers use ‘cost-effectiveness’, ‘institutional priorities’, or ‘patient-centeredness’ as a rubric to prioritize which screening tests or other preventive interventions to offer. An interesting finding in our study was that there was in fact no overriding priority system. Instead, providers typically started with a foundation based on recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and then prioritized based on the available time, the patient’s overall health, a preventive service’s perceived complexity, the patient’s agenda, and the general sense that cancer screening is expected on the part of patients.

Finally, who is the appropriate healthcare provider to deliver preventive health? This study revealed that PCPs continue to have a profound determination to maintain their role in providing preventive care to their patients. The use of team members engaging with the patient is an attractive approach to increase preventive service delivery (Pelak et al., Reference Pelak, Pettit, Terwiesch, Gutierrez and Marcus2015). PCPs readily acknowledged the effectiveness of other staff members such as medical assistants to help increase the flow of patients through the healthcare delivery process. Rose et al. (Reference Rose, Ferraro, Skelly, Badger, MacLean, Fazzino and Helzer2015) point to the effectiveness of pre-screening for patients who are registered for non-acute visit in an academic medical clinic similar to the sites in our study. However, as the ‘team’ approach proliferates, our study shows that PCPs strongly value that a patient’s PCP should be involved in complex preventive care decisions, especially for topics such as cancer screening, in which appropriate responses to patients’ questions would demand the time and expertise of the PCP.

Conceptual model

We undertook this exploratory study to unearth a conceptual framework or model of decision-marking around delivering preventive health recommendations in a clinic-based setting (Earp and Ennett, Reference Earp and Ennett1991). Squires et al. (Reference Squires, Chilcott, Akehurst, Burr and Kelly2016) employed a similar qualitative strategy and built their conceptual model for public health economic evaluation. Their study was informed by literature reviews of key challenges in public health economics. In our study, a framework emerged to illustrate how PCPs acted due to the realities the patients’ needs. This model can be described as ‘Pragmatic Deferral’. As shown in Figure 1, in a non-preventive visit, multiple factors tend to tilt the momentum of a visit away from including preventive care. While time continues to be a factor, time constraints emerged as part of a larger model of decision-making. These include the presence of uncontrolled health conditions, prevention not being part of the visit agenda, not being the patient’s primary longitudinal care provider, or simply not having time. If there is time, then the services delivered are more likely to be short and require less shared decision-making (eg, vaccinations instead of a cancer screening discussion). The barriers and facilitators described in this and prior studies modulate these factors.

Figure 1 Conceptual framework: ‘Pragmatic Deferral’. PCP=primary care providers

This model echoes and builds upon prior work. A pilot study of prostate cancer screening found similar complex barriers and facilitators (Guerra et al., Reference Guerra, Jacobs, Holmes and Shea2007), and one theory pertaining to decision-making in cancer screening describes the process as ‘Making the Most of the Visit’ (Starks and Trinidad, Reference Starks and Trinidad2007). Our model addresses prevention as a whole, rather than focusing on a single topic such as cancer screening. Mirand et al. (Reference Mirand, Beehler, Kuo and Mahoney2003) similarly found that prioritizing ‘secondary’ care issues was a barrier to addressing prevention, and also uncovered the theme of providers’ self-perceived role as a ‘one-stop-shop’ or ‘savior’ as a barrier, a concept that did not arise in our analysis. Jaen et al. (Reference Jaén, Stange and Nutting1994) over 20 years ago developed a theoretical ‘Competing Demands’ model in which the factors influencing preventive health delivery are the patient, physician, and clinical setting. Our model identified similar factors, but because it arises from qualitative data rather than theoretical constructs, it provides detail and adds depth to the analysis of a PCP’s decision-making process. It is also addresses the issue of visit type, and is current to the model of care delivery as practiced today.

Limitations

The interviews we conducted were in an academic setting and providers may be different than those in other practice environments. However, even within this system, providers practiced in a variety of clinical settings, and we believe our efforts to ensure internal reliability made this study exportable to other clinic-based settings. Interviews are an effective way of identifying and exploring perceptions that cannot be discovered with surveys or observation, but can nonetheless be biased. Although we attempted to validate our semi-structured interview guide and scenarios by pilot-testing before implementation, salient topics may have been omitted. Each interviewer was trained to arrange and word each interview question in the same manner but some flexibility was allowed in order to achieve depth of responses, thus potentially resulting in a variation of responses and weakening comparability of answers. In the development of major themes, it is always possible that some meanings could have been lost. Prior studies have shown that providers tend to over-estimate their delivery of preventive services (Woo et al., Reference Woo, Woo, Cook, Weisberg and Goldman1985; Montano and Phillips, Reference Montano and Phillips1995), but as our purpose was to seek decision-making insights of providers, we did not address actual rates of preventive health delivery. As this was a study of providers and their decision-making, it was necessarily provider-centric and although PCPs did report occasions in which the patient initiated preventive care requests, in this research we did not seek to address the patient voice. Our conceptual model arose from the thematic analysis, but it has not been tested in other clinical settings.

Implications for practice

As healthcare systems work toward improving delivery rates of preventive care, they may consider the insights this model provides regarding how PCPs make their decisions. Efforts to increase whether preventive care is delivered in a given clinic visit may be viewed from this lens: PCPs act pragmatically and attempt to triage appropriately, with multiple factors tending to lead to deferral of preventive services. More research is needed to determine whether addressing the barriers and facilitators for these factors may then improve preventive service delivery. This conceptual model of Pragmatic Deferral could be used to guide further research in improving clinic-based rates of preventive health delivery if behavior change on the part of providers is required. Efforts to steer what preventive services are delivered may also be challenging. As we found that there was no single guiding rubric for how a PCP prioritizes which service to address, external efforts to increase certain services will likely need to include the input of PCPs. Finally, as the team-based model grows in popularity, care systems may wish to consider the shared decision-making role that PCPs wish to retain.

In Essential of the U.S. Health Care System, 4th edition, authors Shi and Singh (Reference Shi and Singh2017) pointed out: ‘The ideal role for primary care would include integrated healthcare in the form of comprehensive, coordinated and continuous services offered with a seamless delivery’. Our findings support and give additional substance to the PCP’s role as principal in healthcare. Future qualitative research is needed to continue to understand how new healthcare systems affect decision-making of PCPs.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Ben Thompson and Nieves A. Martinez for assistance with transcription.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. C.J.W. was partially supported internally from the Division of General Internal Medicine by the Stern Family Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

This research was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board HSD no. 49491.