Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is common and is defined as ‘the complaint of any involuntary leakage of urine’ (Botlero et al., Reference Botlero, Urquhurt, Davis and Bell2008) or by ‘the observation of the involuntary loss of urine leakage on examination’(Haylen et al., Reference Haylen, Ridder, Freeman, Swift, Berghmans, Lee, Monga, Petri, Rizk, Sand and Schaer2010). UI affects both sexes; however, it is more common among women (Brocklehurst, Reference Brocklehurst1993; Roe et al., Reference Roe, Flanagan, Jack, Barrett, Chung, Shaw and Williams2011). UI can be detrimental to the social, psychological and physical well-being of the sufferer (Largo-Janssen et al., Reference Largo-Janssen, Smits and Van Weel1992; Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network, 2004). The cost of UI in Sweden and the United States of America accounts for 2% of the healthcare budget (Milsom et al., Reference Milsom, Abrams, Cardozo, Roberts, Thuroff and Wein2002). With the UK healthcare budget for 2011–2012 of £102.7 billion (HM Treasury, 2011), this would equate to spending in the UK of £2.1 billion/year. In addition, many patients find themselves having to buy extra incontinence pads as 81% of primary care providers and 76% of care home services limit the maximum number of pads available per day (Wagg et al., Reference Wagg, Mian, Lowe, Potter and Pearson2005). UI will affect more individuals as the mean age of the population increases (Santiagu et al., Reference Santiagu, Arianayagam, Wang and Rashid2008). However, estimates of the prevalence of UI vary hugely (Roe et al., Reference Roe, Flanagan, Jack, Barrett, Chung, Shaw and Williams2011); this could be owing to differences in the definition and the assumption that people will openly declare their continence problems (Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network, 2004). We have carried out a questionnaire survey to establish the prevalence of UI in a sample of the female population in the United Kingdom.

Methods

Participants and setting

This was a population-based cross-sectional postal evaluation of all (2414) female patients over the age of 21 registered at a single community medical practice in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire (UK). This practice has a higher proportion of white British people than the UK average, in addition, North Staffordshire has higher levels of socio-economic deprivation than the UK average. Participants, who were allocated a unique number so remained anonymous to the research team, were sent a brief self-completion postal questionnaire. In the absence of a response to the original questionnaire within 4 weeks, the questionnaire was resent. Returned questionnaires were scanned at the clinical audit department of the local hospital. A random sample of 247 returned questionnaires was checked manually to ensure accurate scanning and accuracy of the entered data.

Questionnaire content

The questionnaire was designed to identify the most likely classification of UI, bladder obstruction, nocturia, treatments offered and the impact of UI on quality of life. Questions included allowed us to classify participants as having either urinary urge incontinence (UUI) or stress urinary incontinence (SUI). There were also questions relating to quality of life, seeking help and treatment success (a scale of four, from very good to no help). The questionnaire was not piloted but users were involved in its development. A copy of the questionnaire is available from the authors on request.

Analysis

Descriptive data are presented as numbers (raw data) and percentages of responders. This study was one of the several conducted as a collaboration between local primary and secondary care providers to evaluate local service provision. Advice from the local Research & Development Department determined that formal ethical review was not required as this was deemed a service evaluation.

Results

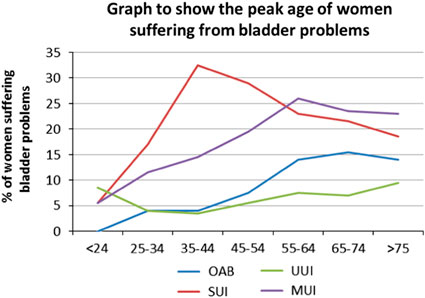

A total of 2414 questionnaires were sent of which 1415 responded (58.6%). The median age-range of responders was 55–64 years (Table 1). The prevalence of UI was 39.9%.Urinary symptoms were common with 7% reporting overactive bladder/UUI, 20% mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) and 24% SUI. A total of 49% were symptom free. Figure 1 presents the age related data for leakage. The peak age of women suffering from SUI was 35–44 years, MUI was 55–64 years and OAB was 65–74years, there were two peaks for UUI, one at 24 years or less, and one over 75 years of age. MUI increases with age until 55–64 years when it levels off, with OAB symptoms showing a similar pattern. Of those women who leaked urine, 84% leaked when ‘coughing, sneezing, exercising or laughing’. For individual symptoms of SUI, 32% had it with cough, 33% with sneeze, 14% with exercise, 17% with laughing and 3% with sex.

Figure 1 Graph to show the peak age of women suffering from bladder problems

Table 1 Demographics of the female population in the study group

Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS)

Daytime frequency of LUTS were experienced by 31%. A total of 28% of women had to pass urine more than once at night; 29% had urge incontinence and 36% had urgency. A total of 10% of the participants had symptoms of bladder obstruction while 50% of responders felt their incontinence started after childbirth. Of those leaking urine, 38.5% leaked a drip, 53% a little, 8% a lot and 0.5% a flood.

Treatment

A total of 17% of participants sought professional help for their symptoms, the most common source being their family doctor; however, multiple sources of advice were often accessed (including nurse, continence advisor or hospital specialist) (Table 2). A total of 18% of women with UI thought there was no help available. Of those who sought help, the commonest treatments were advice/exercise followed by medication, surgery and then bladder retraining. Multiple treatment modalities may have been used by individual patients. Subjective success of treatments can be found in Table 2.

Table 2 Treatment sought by women with urinary incontinence symptoms and perceived success

Quality of life and UI

The majority of patients suffered with their problems for more than a year with 46% suffering symptoms for one to five years and 42% for more than five years. A total of 53% found their bladder problems affected their life ‘hardly at all’. However, 34% were affected ‘a bit’, 9% ‘a lot’ and 4% very much. The majority of people with bladder symptoms (68%) ‘accept it’; 16% are embarrassed; 12% are unhappy and 4% are very unhappy.

Help-seeking behaviour was commonest in women with OAB (42%) followed by 34% of women with MUI and 12.9% in those with SUI. Only 7.4% of women with SUI and 20% of women with MUI reported receiving supervised pelvic floor muscle retraining of at least three months duration. Bladder retraining was offered in only 5.2% of patients who reported UUI and 9.4% of patients who reported MUI.

Discussion

This study provides new insight into the prevalence of UI, which was 39.9% in this sample of UK primary care patients. The relatively high prevalence in this population may be owing to the survey being a postal questionnaire: people may have been less embarrassed and therefore more willing to discuss their problems as compared with telephone interviews or face-to-face contact, with the mode of administration of a questionnaire affecting data measurement and completeness (Bowling, Reference Bowling2005). Community-based populations and postal questionnaires of randomly selected participants have led to higher reported prevalence rates of UI 42% (Hunskaar et al., Reference Hunskaar, Lose, Sykes and Voss2004), 34% (McGrother et al., Reference McGrother, Donaldson, Shaw, Matthews, Hayward, Dallosso, Jagger, Clarke and Castleden2004) and 20% (Perry et al., Reference Perry, Shaw, Assassa, Dallosso, Williams, Brittain, Mensah, Smith, Clarke, Jagger, Mayne, Castleden, Jones and McGrother2000) than, for example, phone interviews (13%) (Irwin et al., Reference Irwin, Milsom, Hunskaar, Reilly, Kapp, Herschorn, Coyne, Kelleher, Hampel, Artibani and Abrams2006). It is, however, difficult to directly compare these prevalence estimates as different studies have used different definitions of leakage, including ‘ever leaked’, one episode in the last year or one episode in the last 30 days. We used the measure ‘do you suffer leakage at any time?’ These differences demonstrate the need for a standardised definition and a core set of questions to determine prevalence and other LUTS. The peak age for SUI in our study was in the 35–44 year age group, which is in keeping with other studies (Correia et al., Reference Correia, Dinis and Lunet2009). Reduction in symptoms after this age may be related to successful treatment, spontaneous resolution of symptoms or alteration in lifestyle, with a reduction in precipitating activities. In addition, pure SUI could change into MUI. The peak for OAB and UUI symptoms was similar, increasing with age, and perhaps should be categorised together (Figure 1). Clearly, the prevalence of OAB/UUI symptoms increases with age, a finding noted in other studies (Correia et al., Reference Correia, Dinis and Lunet2009; Schimpf et al., Reference Schimpf, Patel, O’Sullivan and Tulikangas2009). Rising rates in the elderly may be owing to the factors including a rise in the natural occurrence of idiopathic detrusor activity, changes in risk factors such as increasing body mass index, diabetes (Izci et al., Reference Izci, Topsever, Filiz, Cinar, Uludag and Lagro-Janssen2009; Roe et al., Reference Roe, Flanagan, Jack, Barrett, Chung, Shaw and Williams2011), drug therapies and poor mobility. In our population-based survey, our findings are limited to those participants who had the ability to return their questionnaire; it is likely that it may therefore underestimate the true prevalence of OAB/UUI as women unable to complete the questions may have been at the greatest risk of these symptoms, for example, dementia sufferers (Roe et al., Reference Roe, Flanagan, Jack, Barrett, Chung, Shaw and Williams2011). One way to address this in future studies would be to involve the carers of those unable to fill in or return their questionnaires.

The NICE guidelines in the United Kingdom (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2013) recommended that women with SUI and MUI are offered supervised pelvic floor muscle training of at least three months duration; only 7.4% of women with SUI and 20% of women who reported MUI reported receiving this treatment. NICE also recommends that for women with UUI or MUI that bladder retraining should be offered; only 5.2% of patients who reported UUI and 9.4% of patients who reported MUI recall receiving this therapy. This would therefore indicate that further education is required of healthcare professionals in conservative management of these condition.

Only 17% of women responding to this questionnaire had sought professional help. Of those participants who reported the amount of urine they leaked, the positive response level rises to 31%. This is similar to two other studies with 28% of women seeking advice (Legace et al., Reference Legace, Hansen and Hickner1993; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Hassel and Nicolaas1999). This is in keeping with research on illness behaviour where not seeking advice is regarded as the ‘norm’, rather than the exception (Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Hassel and Nicolaas1999). Research indicates that of people who experience symptoms on a regular basis, only a small percentage of these will seek help, this being the ‘illness or clinical iceberg’ (Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Hassel and Nicolaas1999). Owing to the low percentage of women in our study seeking help (17%), further analysis was conducted to determine who was most likely to seek help. As the amount of urine women leak increased, more women sought help. Women with OAB were the most likely to seek help and women with SUI least likely, a finding also noted by Seim et al. (Reference Seim, Sandvik, Hermstad and Hunskarr1995). This may be because SUI leaks are usually smaller and more predictable. In addition, OAB and UUI symptoms led to greater psychological stress, possibly owing to the unpredictable nature of the symptoms and the larger volume leaked (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Visco, Fantl and Bump2002), triggering help-seeking behaviour earlier. Triggers may include interference with personal relations; sanctioning that help is required from friends or family and interference with work or physical activity (Zola, Reference Zola1973). Of importance in recognising the unmet need of UI sufferers in the community is the fact that major depression is three times more common in those with UI (Melville et al., Reference Melville, Walker, Katon, Lentz, Miller and Fenner2002). Therefore, if we proactively recognise and treat UI, this burden in the community may be reduced as well as sexual and employment problems, and avoidance of healthy activities such as sport (Sinclair and Ramsey, Reference Sinclair and Ramsey2011).

This study has several strengths. It achieved a good response rate, from a large number of women and asked about a range of symptoms relevant to UI. It sampled from a single general practice, which may limit the generalisability of these findings although the source population is broadly similar to the nationally expected demographics.

Education is required for both patients and doctors, especially in the community where most treatments can occur (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Tansey, Jackson, Hyde and Allen2001; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006). Healthcare knowledge, experience, time and organisational constraints all play their part in forming a barrier to provision of first-line treatments in primary care (Roe et al., Reference Roe, Flanagan, Jack, Barrett, Chung, Shaw and Williams2011). This results in more referrals into the secondary care setting (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Tansey, Jackson, Hyde and Allen2001) and less pro-active questioning that would allow the elicitation of symptoms that the patient may be too embarrassed to mention spontaneously. The National Audit on Continence Care in the United Kingdom (Wagg et al., Reference Wagg, Harari, Husk, Lowe and Lourtie2010) summarised that the great majority of continence services are poorly integrated across acute, medical, surgical, primary, care home and community settings, resulting in disjointed care for patients and carers. Wagg et al. (Reference Wagg, Harari, Husk, Lowe and Lourtie2010) specifically mentions routine questioning of incontinence symptoms whenever healthcare givers encounter elderly people and others at high risk of incontinence.

Surprisingly, women seem to put up with bladder problems for a long time: 88% had bladder problems for more than one year and 42% problems for more than five years before seeking help. This is consistent with other studies with a duration of incontinence greater than five years in 49% women (Seim et al., Reference Seim, Erikson and Hunskaar1996) and may be owing to factors already mentioned, such as embarrassment, acceptance, the feeling that is it the norm, lack of education and knowledge of services available.

Conclusion

This primary care study confirms that UI and LUTS in women are a major problem in society. The unmet need in these women may be a major use of healthcare resource and planning around improving services should be considered with the information this study provides. It appears that the level of patient knowledge and health-seeking behaviour surrounding the nature of the problem and possible alternative treatments is very low. A significant effort from healthcare providers has to be made to improve patient information about the nature of UI and its effects on life both in the short and the long term, as well as about available treatments.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thanks the patients and staff of Kingsbridge Medical Practice, Staffordshire, UK for their help and participation in this project.