Background

Fibromyalgia (FM) is characterised by widespread pain, fatigue and cognitive dysfunction (Doebl et al., Reference Doebl, Hollick, Beasley, Choy and Macfarlane2021). FM has an estimated prevalence of 5.4% within the United Kingdom (UK) (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Atzeni, Beasley, Flüß, Sarzi-Puttini and Macfarlane2015) and places significant burden on patients, primary care and the wider National Health Service (NHS) (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Martinez, Myon, Taïeb and Wessely2006; Soni et al., Reference Soni, Santos-Paulo, Segerdahl, Javaid, Pinedo-Villanueva and Tracey2020).

FM is challenging in part due to the range of symptoms. These symptoms overlap with numerous other conditions, such as chronic fatigue syndrome (Åsbring and Närvänen, Reference Åsbring and Närvänen2003) and functional neurological disorder (FND) (van der Feltz-Cornelis et al., Reference van der Feltz-Cornelis, Brabyn, Ratcliff, Varley, Allgar, Gilbody, Clarke and Lagos2021). There is evidence of a correlation between FM and psychiatric disorders, with 13–80% of FM patients having comorbid anxiety or depression (Galvez-Sánchez et al., Reference Galvez-Sánchez, Duschek and Del Paso2019). Scepticism towards FM patients can be driven by invisible symptoms (e.g., pain) and the stigma of FM being a ‘womens’ illness’ (Sallinen et al., Reference Sallinen, Mengshoel and Solbrække2019). There are often inconsistencies between General Practitioners (GP) in diagnosis and treatment (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Gebke and Choy2016), and there is currently no objective diagnostic test to confirm FM. FM patients often undergo numerous medical tests that come back normal (Goldenberg, Reference Goldenberg2009), are frequently misdiagnosed or have a delay receiving a diagnosis (Baron et al., Reference Baron, Perrot, Guillemin, Alegre, Dias-Barbosa, Choy, Gilet, Cruccu, Desmeules, Margaux and Richards2014). Conflicting explanations for FM persist. For example, whilst FM is classified under chronic primary pain within the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics, 2022), it is also classified as a ‘medically unexplained symptom’ condition – in which thoughts, feelings and stressors may explain physical symptoms – by the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCPSYCH, 2023). A UK-based survey reported that whilst 66% of GPs felt they could do more to help FM patients, 41% felt that the criteria for FM is unclear and 30% were uncertain about treatments (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Myhal, Thornton, Camerlain, Jamison, Cytryn and Murray2010). Over 1 in 5 (23%) stated that FM patients are ‘malingerers’ and 76% found that FM patients are time consuming and frustrating (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Myhal, Thornton, Camerlain, Jamison, Cytryn and Murray2010).

Research with FM patients describes a long journey to validation, a diagnosis often taking years to obtain, featuring interactions with a ‘merry-go-round’ of clinicians – some of which questioned the legitimacy of their illness (Mengshoel et al., Reference Mengshoel, Sim, Ahlsen and Madden2018). Whilst patients emphasise the importance of trust and the patient–doctor relationship to their prognosis, 38% delay visiting their doctor because they fear not being taken seriously, and 59% report difficulties trying to communicate their symptoms (Choy et al., Reference Choy, Perrot, Leon, Kaplan, Petersel, Ginovker and Kramer2010; Doebl et al., Reference Doebl, Macfarlane and Hollick2020).

Despite these difficulties, there are recommendations that FM should be managed within primary care as GPs are patient’s first point of contact, particularly for early intervention (Endresen, Reference Endresen2007; Rheumatology GIRFT Programme National Speciality Report, 2021). In which case, there is an urgent need to improve the experience of consultations for both FM patients and GPs.

This review aimed to explore the perspectives and experiences of FM patients and primary health-care clinicians. It is hoped that by synthesising the evidence from both patients and clinicians, it will create a holistic view of what issues are experienced and how they may be overcome.

Methods

This qualitative evidence synthesis was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (registration record CRD42020201717) and followed the Cochrane Handbook for Qualitative Evidence Synthesis guidelines (Noyes et al., Reference Noyes, Booth, Cargo, Flemming, Harden, Harris, Garside, Hannes and Pantoja2022). Reporting has been guided by the ENTREQ checklist (Tong et al., Reference Tong, Flemming, McInnes, Oliver and Craig2012).

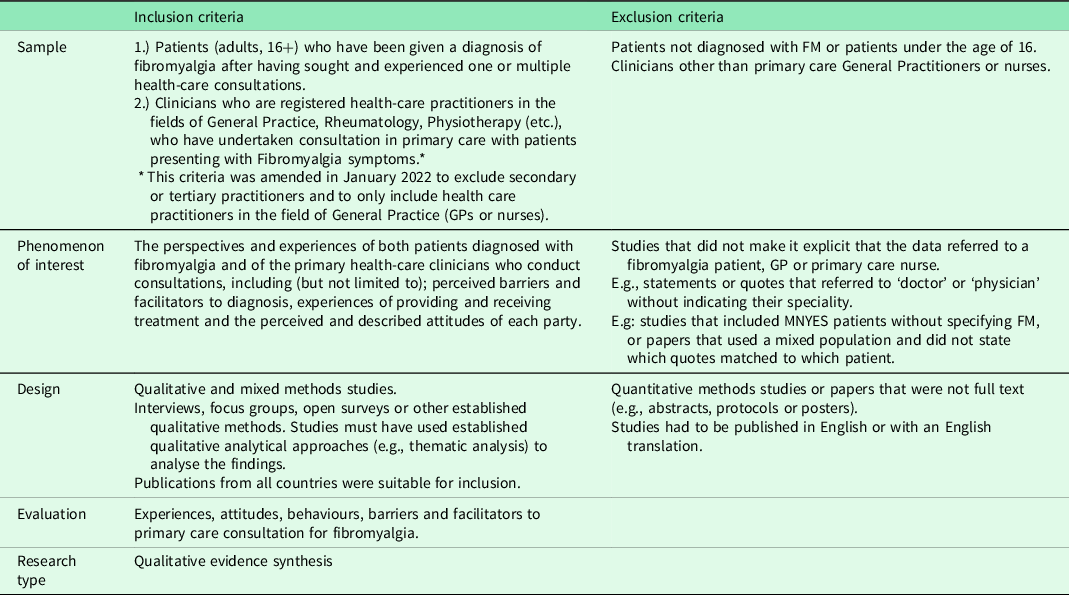

The criteria provided in Table 1, developed using the SPIDER framework (Cooke et al., Reference Cooke, Smith and Booth2012), were used to assess potentially eligible studies.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria (SPIDER)

Data sources

A pre-planned search strategy for four databases (MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL and CINAHL) was developed through collaboration between three authors (AB, MB and CVDFC). The search strategy combined key terms for the populations and phenomenon of interest with terminology for qualitative methodology using the Boolean operator AND (Appendix 1). Publications from any country were eligible if they were in English or with an English translation. Databases were searched from inception to November 2020, with an updated search between November 2020 and 2021. Manual searches of reference and citation lists were completed for studies meeting the inclusion criteria.

Screening

Titles were screened by AB before abstract and full-texts were screened independently by two authors (AB and KJ/MB). The systematic review software Rayyan was used for screening and the blinded recording of decisions. Discrepancies were resolved by a third author (CVDFC). An inclusion/exclusion checklist was used to promote consistency.

A data extraction form was piloted by two authors (AB and MB). The Google form was designed to capture key characteristics of the included papers and participant characteristics (e.g., geographical location, study population and method of data collection). Data extraction was conducted by two authors independently (AB and MB/FR/EM).

Literature synthesis

PDF versions of all the included studies were downloaded for manual data extraction and synthesis. Coding was line-by-line and inductive, using quotes and interpretations provided within the ‘results’ and ‘discussion’ sections. Themes given by the authors were not coded and compared as the study aimed to provide a synthesis across patient and clinician data, rather than to review the consistency of themes across studies, and as we anticipated the inclusion of mixed-population studies. However, familiarisation with the included studies and wider literature may have influenced coding. Initial coding frameworks for patient and clinician data were developed by two authors (AB and KJ) independently coding three papers and reaching a consensus on initial second-order constructs. Thematic synthesis was used for analysis as a method useful for assessing intervention need, whilst its inclusion of line-by-line coding allows for the translation of concepts across studies (Thomas and Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008; Barnett-Page and Thomas, Reference Barnett-Page and Thomas2009). Coding frameworks were referred to throughout and expanded upon based on the emerging data. The final frameworks mapped out the translation of data from relevant first- and second-order constructs into codes, sub-themes and themes.

The coded data were re-read alongside the study aims to assist in the development of themes. Themes were considered as written interpretations, mapped onto data and visualised using diagrams. Twenty-nine codes were mapped onto three overarching themes by AB. Once themes had been developed, all authors reviewed the data coding, mapping and interpretations. AB and KJ were mindful throughout analysis of their biases as patients who have experienced difficult GP interactions and, in the case of AB, having family with FM. Discussions were had during analysis which allowed for biases to be acknowledged and checked. On one occasion was this notable enough to warrant discussion, after which a consensus was reached.

Themes were discussed with a patient advisor (JB, symptomatic since 2013, diagnosed with FM in 2015). JB reviewed the themes, providing detailed feedback to each and how they related to their experience. Themes were felt to resonate to their experience but were refined according to their feedback.

Quality Assessment (QA)

Quality assessment (QA) was conducted by two authors independently (AB and KJ/FR/EM) using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018) checklist. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Results

Study characteristics

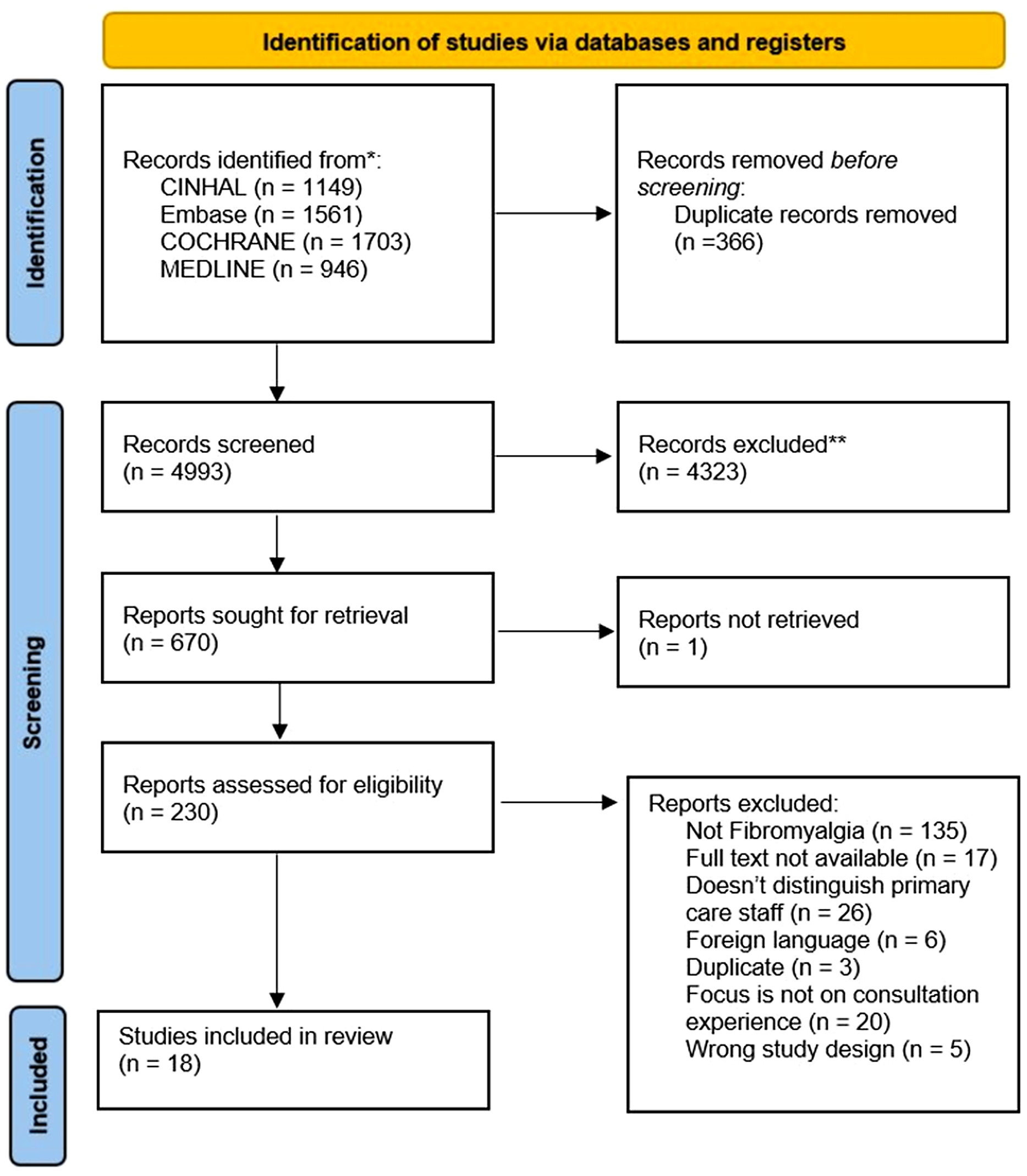

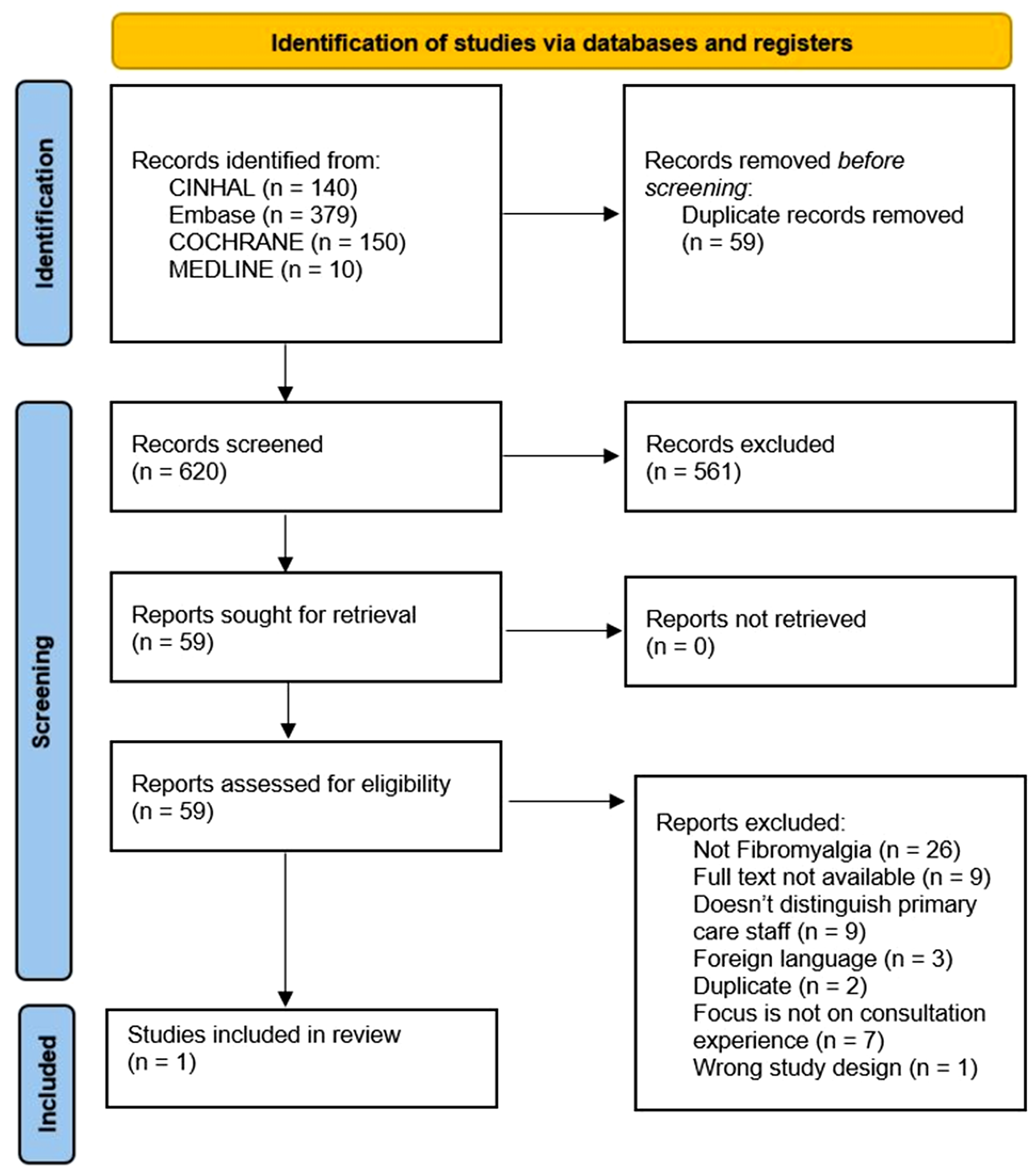

The search strategy returned 6038 studies. Altogether, 289 were full text screened, and 19 studies met the inclusion criteria (Figures 1 and 2). Reference and citation lists revealed another 11 papers, leading to 30 included papers.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow2021). Initial search (inception –November 2020).

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow2021). Second search (November 2020–2021).

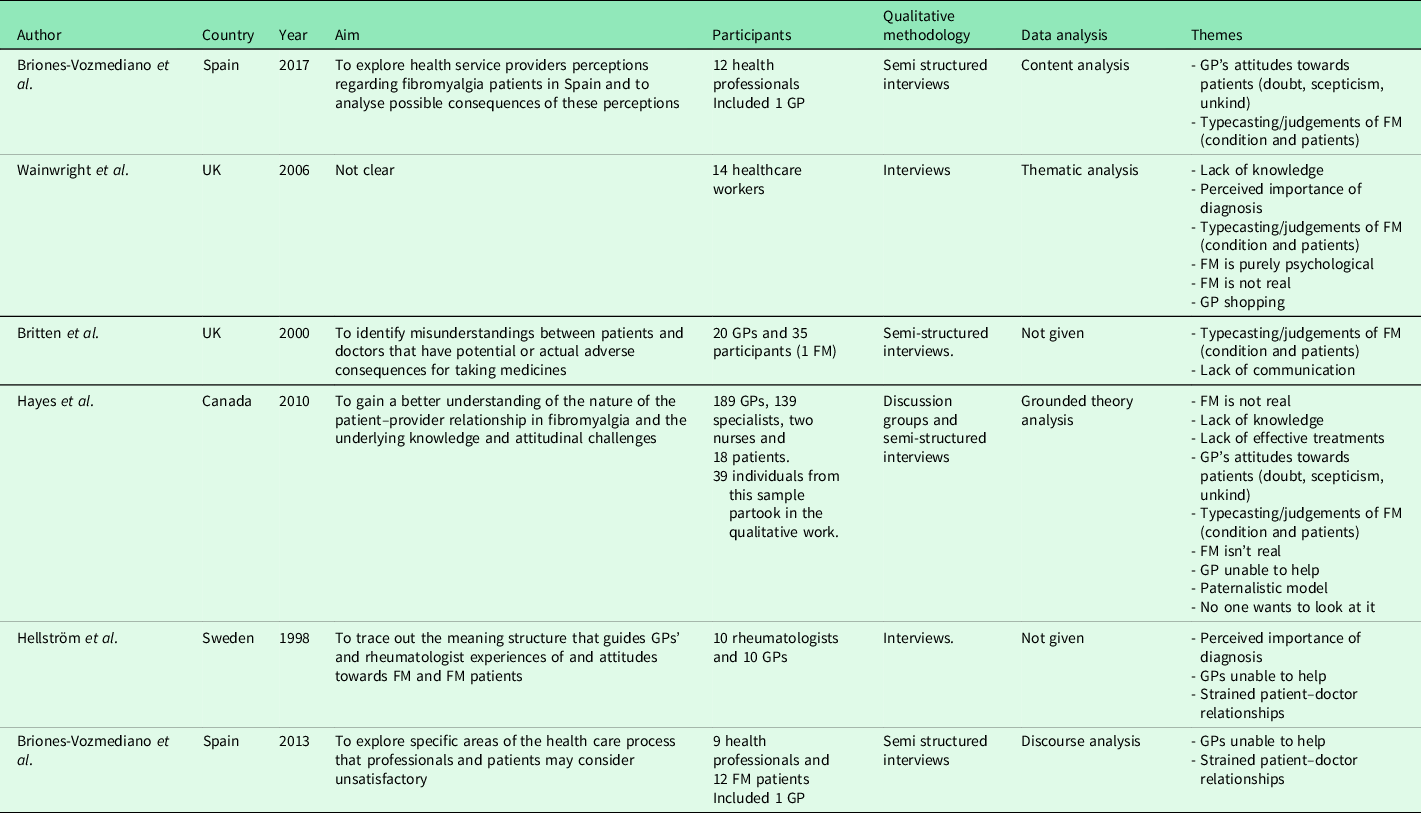

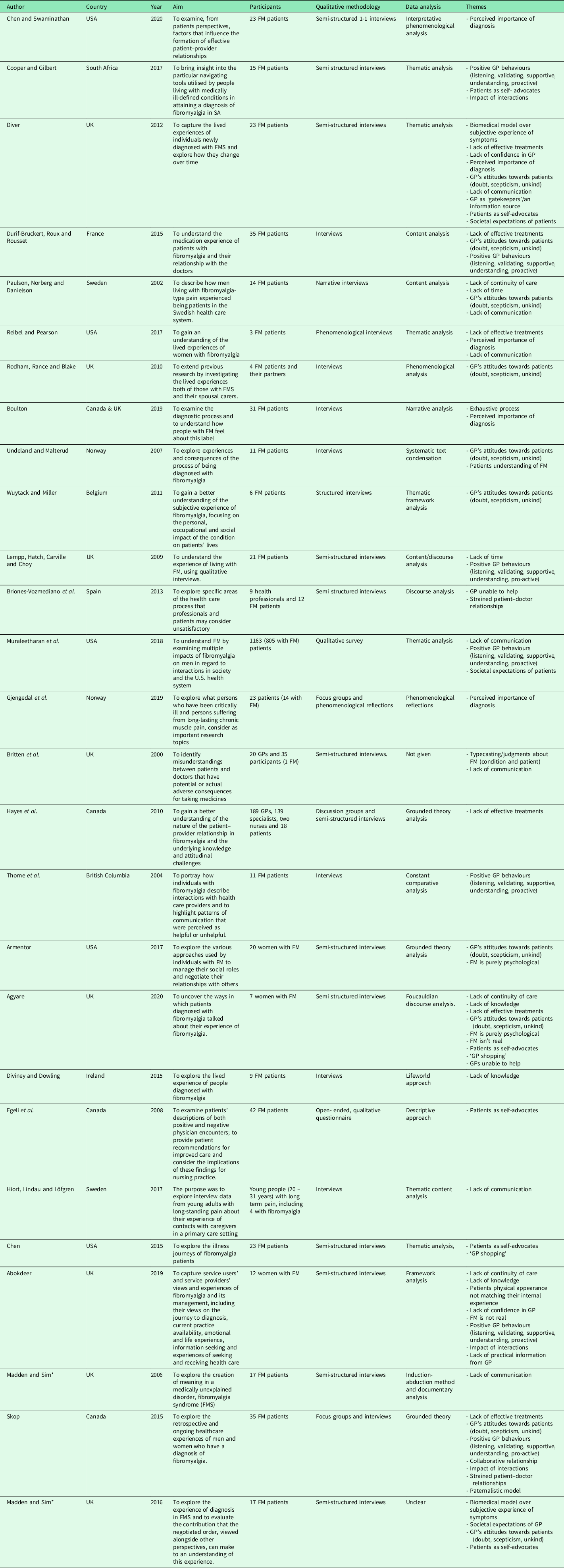

The characteristics and codes from the 30 studies are illustrated in Tables 2 and 3 and further in Appendix 2. Two papers appear to include different data from the same study (Madden and Sim, Reference Madden and Sim2006, Reference Madden and Sim2016), indicated with * within Table 3.

Table 2. Characteristics and codes from clinician studies.

FM = Fibromyalgia, GP = General Practitioner.

Table 3. Characteristics and themes from FM patients

* Associated papers.

FM = Fibromyalgia, GP = General Practitioner.

Six papers explored how primary care practitioners experience consultations for FM. All six studies included mixed healthcare populations (e.g., GPs and secondary/tertiary care doctors). None recruited primary care nurses. Totally, 28 studies explored FM patients’ experiences, with the majority exclusively including FM as their patient population. Studies were conducted across ten countries, predominantly used qualitative interviews, and reported a range of analyses (Tables 2 and 3).

Quality assessment

The studies ranged in quality. Whilst 7/30 were of high quality, 23 displayed at least one methodological limitation (Appendix 3). Limitations most commonly related to the relationship between the researcher and participant, as 22/30 papers reported this insufficiently. Other common limitations surrounded the rigour of data analysis (7/30), data collection (6/30), statement of study findings (6/30) and ethics (5/30).

Thematic synthesis

Three overarching themes were identified: life turned upside down, negative cycle and breaking the cycle.

Theme 1: Life turned upside down

This theme lends itself to sociological theories of chronic illness, including biographical disruption and legitimation (Bury, 1982, Reference Bury1991) and chaos narratives (Nettleton et al. Reference Nettleton, Watt, O’Malley and Duffey2005) by reflecting how once FM symptoms start patients may find themselves no longer meeting their own expectations and those of society (Supplementary material 2).

Western societal expectations dictate that if you feel sick you go to your GP (Diver, Reference Diver2012, p.192). The GP will identify the problem, offer treatment and resolve your illness. FM patients usually begin their journey by experiencing invisible symptoms that stop them from doing usual activities and actions that they previously could and would expect to be able to, do. Following the expected pathway, they seek help from their GP. Contrary to normal expectations, the studies highlighted how GPs were often unable to help their symptoms, identify what was causing their illness and sometimes did not believe their illness was real.

‘They considered themselves to be fulfilling social and cultural obligations by attending their GP and being compliant with tests and treatments offered and yet their situation remained the same or worsened’. Author quote. Diver (Reference Diver2012). p.224.

Patients often reported receiving alternate explanations for their illness that were later proved wrong. These explanations did not fully fit their symptom experience, but patients were willing to accept them due to the trust they placed in their GP.

‘You go blindly on, you’re not really satisfied, but then I thought well there’s people a lot worse off than me. If that’s what she [GP] says it is, that’s what it must be’. Patient quote. Madden and Sim (Reference Madden and Sim2016). p.97.

Some patients found the consultation itself flipped upside down – from an interaction designed to help them to an interrogation about their credibility. Patients were questioned on the legitimacy of their illness, dismissed and encountered unsympathetic GPs. Patients’ credibility was an issue both prior and post-diagnosis.

‘They still didn’t want to believe it…I had to change GP. I err went through a very bad time with the GP, who just said I didn’t have anything wrong with me, still wouldn’t, you know, didn’t want to accept the diagnosis’. Patient quote. Rodham et al. (Reference Rodham, Rance and Blake2010). p.71.

The studies illustrated that some patients felt their credibility in question because they experienced invisible symptoms, received inconclusive diagnostic tests and because their physical experience often did not match their physical appearance.

‘Participants described how they were questioned at times about whether they genuinely had been ill and suffering with pain by people at work, and even by GPs, as the result of looking physically well’. Author quote. Abokdeer (Reference Abokdeer2019). p. 89.

Some patients reported experiencing scepticism, dismissal and no objective confirmation of their illness or its severity from their GP, despite pursuing the socially correct path to validation. This led patients to feel isolated, uncertain and to begin doubting themselves.

‘They were influenced by their inability to live their “normal” lives and began to lose confidence in their own explanations for their symptoms as well as those provided by their GP’. Author quote. Diver (Reference Diver2012). p.196.

In line with Nettleton et al. (Reference Nettleton, Watt, O’Malley and Duffey2005), across studies it appeared to be the uncertainty that was driving the ‘chaos’ patients felt. Diver (Reference Diver2012, p.223) reported that patients who received a diagnosis early experienced less ‘chaos’. This may be because diagnosis provided patients with a certainty in a period of extreme uncertainty – allowing them insight into the severity of their condition, the reality of what their illness meant for their lives, and a degree of legitimation (Bury, Reference Bury1991).

For patients filled with uncertainty and chaos, it led to actions such as ‘GP shopping’ – consulting multiple GPs – and self-advocacy. This dislike of uncertainty appears to clash with GP narratives, in which they appeared comfortable sitting in the uncertainty with the option to refer the patient on.

‘[…] the interviews gave the impression that the GPs were more accustomed to living with uncertainty and with a less structured practice than hospital clinicians’. Author quote. Hellström et al. (Reference Hellström, Bullington, Karlsson, Lindqvist and Mattsson1998). p.235.

The traditional paternalistic model assumes that the doctor knows all – including what your illness is, what decisions, actions and treatments should be given – and that an ‘unwavering trust’ should be given (Lee, Reference Lee2007; Murgic et al., Reference Murgic, Hébert, Sovic and Pavlekovic2015). We theorise that the expectation this model has set up presents a conflict for FM patients if their GP doesn’t have the knowledge and/or options to help – further driving the feeling that their lives had been turned upside down.

‘It’s very stressful because when you go to the GP I think you want them to know. You expect them to be able to pinpoint at what you’re suffering from’. Patient quote. Agyare (Reference Agyare2020). p.114.

Moreover, despite a diagnosis potentially reducing the experience of chaos there was a sense that patients were forced to assimilate their status as a FM patient into their identity and were disappointed with what that meant.

‘She was disappointed, because she knew the word ‘fibromyalgia’ would cling to her, even if she died of cancer or a heart attack’. Author quote. Undeland and Malterud (Reference Undeland and Malterud2007). p.252.

Theme 2: Negative cycle

Across the included studies, there was evidence of positive and negative interactions. Within the negative narratives, there emerged evidence of a cyclic relationship in which GP and patient factors fed into each other, worsening the consultation process over time (Supplementary material 3).

Lack of knowledge was predominant within this theme from both perspectives and fed into all aspects – from beliefs about the underlying mechanisms of FM and its existence, the knowledge held by GPs and patients, to the limited treatment options available.

‘It does have some criteria, and its complex, and we definitely don’t understand it as well as we need to’. GP quote. Hayes et al. (Reference Hayes, Myhal, Thornton, Camerlain, Jamison, Cytryn and Murray2010). p.387.

The challenges created by the lack of knowledge were further exacerbated by negative GP attitudes, including the belief that FM patients are ‘soft’ and need to ‘liven up’ (Briones-Vozmediano et al., Reference Briones-Vozmediano, Öhman, Goicolea and Vives-Cases2018, p.1682). Doubt over the validity of FM as a disease was also exhibited, particularly over the underlying cause (biomechanical or psychosocial).

‘They are patients that…towards them whom I feel rejection, I have to admit’. GP quote. Briones-Vozmediano et al. (Reference Briones-Vozmediano, Öhman, Goicolea and Vives-Cases2018). p.1682.

‘I’m not convinced […] That’s my problem with Fibromyalgia, I’m not convinced at all’. GP quote. Hayes et al. (Reference Hayes, Myhal, Thornton, Camerlain, Jamison, Cytryn and Murray2010). p.387.

Further difficulty and doubt arose due to a lack of objective markers of the disease, with patients frequently returning inconclusive medical tests and being unable to confirm their symptoms objectively.

‘I kept going back to the GP over and over again with the pain and he sent me for various tests but couldn’t find anything wrong’. Patient quote. Boulton (Reference Boulton2019). p.812.

Patient narratives demonstrated an expectation that the GP should have all the answers to their illness. GPs’ were viewed as gatekeepers to treatments and information. This is likely to be further driven by patients’ dependence on their doctor confirming their sickness to other authorities, for example; to claim benefits or receive sick leave. Conflict arose when patients did not receive the help they expected, gained no knowledge about their illness or were offered diagnoses that did not fit.

‘The GP, you know, didn’t have a clue about fibromyalgia, didn’t have a clue about what my pain was’. Patient quote. Abokdeer (Reference Abokdeer2019). p.81.

Whilst patients felt that they were fulfilling their expected role, they were faced with conflict when the GP did not appear to fulfil theirs. In an attempt to resolve this conflict, patients learnt to self-advocate, seeking out other GPs and asking for further tests, treatments and referrals.

‘Participants talked about experiencing resistance towards their doctors and GPs and talked about trying to convince them that they were ill, hence the multiple visits, long diagnostic journeys and insistence on referrals to other medical specialists’. Author quote. Agyare (Reference Agyare2020). p.102.

This self-advocacy clashes with the paternalistic model, in which patients are expected to take a passive role (Bissell et al., Reference Bissell, May and Noyce2004). Instead, it pushes a collaborative, patient-centred agenda in consultations where the GP may not always be willing to accept this model. GP narratives, in turn, illustrated a resistance towards patients and the development of an understanding that these are a difficult patient group, whose use of healthcare is reflective of attention-seeking behaviour. Concern was expressed that they could ‘fall in’ with patients’ agendas (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Myhal, Thornton, Camerlain, Jamison, Cytryn and Murray2010. p.389.). There was a sense that GPs began to typecast patients, wanting a test to assess how ‘worth it’ patients were to work with (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Myhal, Thornton, Camerlain, Jamison, Cytryn and Murray2010. p.389) and consciously placing limits on what they were happy to sign off on.

‘They feel mentally like no one understands them, and this is part I think, of the characteristics of the profile of fibromyalgia…that wherever they go no one pays attention’. GP quote. Briones-Vozmediano et al. (Reference Briones-Vozmediano, Öhman, Goicolea and Vives-Cases2018). p.1682.

The cycle rounds off with recognition of the limited treatment options. There is no cure for FM and the limited number of treatment options available are not always effective. Moreover, when prescribing pain medication, the available drugs often have significant side-effects and can cause dependency, leading GPs to be justifiably cautious. GPs are likely to feel a degree of helplessness and frustration when consulting with FM patients because they have limited – possibly ineffective – options.

‘No matter what you give them, the pain doesn’t go away’. GP quote. Briones-Vozmediano et al. (Reference Briones-Vozmediano, Vives-Cases, Ronda-Pérez and Gil-González2013). p.21.

Evidence is emerging that the knowledge, attitudes, actions and options of GPs and patients can negatively feed into each other, interacting with medical models to produce a detrimental cycle that effects both parties. The cycle teaches patients that their GP is nolt interested in their symptoms, and as a result they may withhold information, experience isolation and a worsening of their symptoms. GPs learn that FM patients are unrewarding, difficult, frustrating and perceive that they will never be able to do enough to help. Factors within the cycle are likely to be exacerbated by practical barriers, including lack of time and continuity of care.

‘I think that the bottom line is no one really wants to look at it’. GP quote. Hayes et al. (Reference Hayes, Myhal, Thornton, Camerlain, Jamison, Cytryn and Murray2010). p.388.

Theme 3: Breaking the cycle

However, by no means was the only narrative chaos and conflict. Whilst the data were relatively thin and lacked data from the GP perspective, studies did provide evidence of supportive, facilitating patient–doctor relationships, with a clear goal to help patients (Supplementary material 4). In these narratives, neither the patient nor GP appeared to fall into the negative cycle illustrated in Theme 2.

Positive patient narratives described the importance of legitimisation, validation and being taken seriously. Legitimisation of FM led some patients to a better healthcare experience and outcomes.

‘She expressed that finding a GP who accepted her condition proved to be a crucial element in shaping her illness experience and outcomes positively’. Author quote. Cooper and Gilbert (Reference Cooper and Gilbert2017). p.347.

Diagnosis appeared to be used by some GPs as a tool to provide patients with legitimacy, confirming that their condition was real whilst also allowing the GPs a natural transition to progress with their care plan. Diagnosis acted as a bridge between the GP and patient, allowing them both to meet a need. This is an interesting contrast to the narratives of those who appeared sceptical and were against providing the diagnosis, believing the label misleading, detrimental or of little value.

‘As well as reassuring the patient, the ascription of a diagnosis of Fibromyalgia may also mark a transition in the consultation, effectively bringing the “work up” to a close and leading to the deployment of treatment options’. Author quote. Wainwright et al. (Reference Wainwright, Calnan, O’Neil, Winterbottom and Watkins2006). p.82.

Legitimisation was also facilitated through effective communication and reciprocal patient–doctor relationships. Patients who described their GP as engaging in active listening, being supportive and accepting and giving clear guidance were more satisfied and had better outcomes. One quote noted how the GP saying, ‘I understand how you feel’ provided the patient with a ‘sense of validation and legitimacy’ (Skop, Reference Skop2015, p.180). This contrasts with negative accounts, in which GPs were described as ‘sympathy not there, empathy not there’ (Agyare, Reference Agyare2020, p.100), not providing ‘proper conversation’ (Paulson et al., Reference Paulson, Norberg and Danielson2002, p.91) and not giving ‘straight answers’ (Hiort et al., Reference Hiort, Lindau and Löfgren2017, p.91). The need for clear, open and effective communication was consistently highlighted, as the studies described encounters with misaligned priorities, miscommunication and assumptions about the other party.

Medication presented an interesting example of miscommunication. Britten et al. (Reference Britten, Stevenson, Barry, Barber and Bradley2000, p.486) described a FM patient wanting to stop their painkillers whilst their GP described the patient as someone who ‘loves taking medicines’. This disparity was evident in other narratives, with patients describing how they felt ‘fobbed off’ through their GPs use of medication, believing them to be an out used if they didn’t know what the problem was. ‘They all prescribe different medication because they don’t really know what it is’. Patient quote. Hayes et al. (Reference Hayes, Myhal, Thornton, Camerlain, Jamison, Cytryn and Murray2010). p.388.

Another overarching finding was the need to improve knowledge. Whilst GPs acknowledged FM as an uncertain condition that required better understanding, patients expressed that the overall lack of knowledge made it difficult for them to manage their FM, and that improvements would result in better patient outcomes.

‘If General Practitioners understood it yes, it would be a lot better for everybody and it would help I think more and more people with fibromyalgia to – not get better but of course feel better at least’. Patient quote. Diviney and Dowling (Reference Diviney and Dowling2015). p.5.

Discussion

This review synthesised the experiences of GPs and FM patients from 30 qualitative studies published across 10 countries. The studies provide an in-depth understanding of how patients and GP’s experience primary care consultations for FM. The studies varied in quality, with 7 being assessed as high quality and 23 displaying at least one weakness. Findings from this review indicate that conflict between GPs and FM patients can exist within primary care, but that clear, effective communication and reciprocal patient–doctor relationships could help overcome these difficulties. A start would be to acknowledge the difficulties faced by each party. It needs to be acknowledged that when FM patients visit primary care, they are likely to be in a state of uncertainty and chaos. The experience of invalidation and inability to receive answers exacerbates this and can have a negative impact on their outcomes (e.g., anxiety/depression, Supplementary Material 1). GPs appeared to be more comfortable sitting in uncertainty than patients because they have the option to refer on. Considering the argument that GPs are best placed to manage FM (Endresen, Reference Endresen2007), the uncertainty may need to be addressed.

Whilst the NHS transitions into a more patient-centred model of healthcare, the authors speculate whether FM experiences greater resistance to this change than conditions with a recognised pathophysiology. Whilst the paternalistic model has constructed the doctor as a superior figure of knowledge, the transition to patient–doctor collaboration would require an admission that medicine knows very little about FM. GPs cannot have endless knowledge, and there should be an understanding from patients that they cannot know everything. Encouraging better communication and transparency about what GPs do know and can offer may ultimately improve both patient outcomes and GP satisfaction.

It is also important to consider these findings in relation to context. FM is controversial, having been considered psychogenic throughout the 19th–20th century (Pikoff, Reference Pikoff2010), before being classified as a somatic symptom disorder by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Walitt, Katz and Häuser2014). FM is currently classified as a condition caused by stress and emotional distress by the RCPSYCH; however, there has been an increasing shift through the 21st century towards a physical explanation.

To guide clinicians, classification criteria for FM have been produced (Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Smythe, Yunus, Bennett, Bombardier, Goldenberg, Tugwell, Campbell, Abeles, Clark and Fam1990; Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Clauw, Fitzcharles, Goldenberg, Katz, Mease, Russell, Russell, Winfield and Yunus2010; Macfarlane et al., Reference Macfarlane, Kronisch, Dean, Atzeni, Häuser, Fluß, Choy, Kosek, Amris, Branco and Dincer2017). Whilst this review highlights that there is still much work required to improve consultations, as four out of six studies including GPs were conducted on or before 2010 perhaps their data simply does not reflect updated knowledge, criteria and the attitudinal shift seen over the last ten years. New guidance on the diagnosis of FM has been produced by the Royal College of Physicians (2022). It will be interesting to see how their implementation changes experiences going forward.

This review is supported by the wide breadth of studies included. Whilst the authors cannot state they achieved theoretical saturation as further studies could have provided novel information (Booth, Reference Booth2016), the majority of data fit into existing codes. This review was developed following the Cochrane guidelines (Noyes et al., Reference Noyes, Booth, Cargo, Flemming, Harden, Harris, Garside, Hannes and Pantoja2022) and ENTREQ checklist (Tong et al., Reference Tong, Flemming, McInnes, Oliver and Craig2012). Clear attempts to reduce bias were made through double abstract/full-text screening, data extraction, quality assessment and the development of coding frameworks. The review may be limited in that title screening and coding were done by a single author. Some relevant studies could have been missed, or different themes could have been derived if multiple authors had coded. However, we have mitigated against this due to the broad criteria applied at title screening, and as all authors – each with a range of perspectives and backgrounds (Appendix 4) – were required to check coding made logical sense to the data.

Another limitation was the inclusion of studies written in English or with an English translation. A more comprehensive search strategy would have included international databases, such as LILACS, improving the generalisability of this review and reducing the risk of language bias. However, as this review has framed the issue in the context of the UK NHS the inclusion of cross-cultural studies may limit the findings. As the NHS has a unique infrastructure, some data may not relate or be feasible. For example, ‘GP shopping’ may occur less within the NHS as there will be a limit to how many different GPs patients can see within their registered practice.

As AB and KJ identified personal experiences that could have biased interpretations, possibly causing patient narratives to be read more sympathetically, there is the potential for author bias. Efforts were made to minimise this through open conversation that allowed for biases to be checked.

Future research should include greater GP input, to understand if and how updated guidance has influenced modern practice and to explore which patient behaviours frustrate GPs and why. Research should also explore what causes a good consultation from the GP perspective – including if any patient actions could improve consultations. Moreover, this review cannot give an accurate estimate of how common these issues are. Considering the publication of later guidance, attitudes amongst GPs may have evolved since the survey by Hayes et al. (Reference Hayes, Myhal, Thornton, Camerlain, Jamison, Cytryn and Murray2010).

Research may wish to explore the implementation of an intervention to improve FM consultations within the NHS. Previous clinical trials have developed enhanced care interventions and have shown some initial, albeit limited, promise (Byrne et al. Reference Byrne, Scantlebury, Jones, Doherty and Torgerson2022). The MSS3 trial (Mooney et al. Reference Mooney, White, Dawson, Deary, Fryer and Greco2022) will soon provide data on the impact of symptom clinics within primary care, and future research may also wish to explore if other interventions could benefit patient outcomes and/or GP satisfaction within the context of the NHS.

Conclusion

The findings from this review suggest that the chaos and uncertainty experienced by FM patients can clash with the attitudes and actions of GPs to produce a negative cycle that can undermine primary care consultations. Legitimisation, clear communication and effective patient–doctor relationships have been evidenced to break this cycle and may also improve patient outcomes and GP satisfaction. Future research should conduct further qualitative investigation into the GPs experience and focus on developing an enhanced care intervention that could be implemented within primary care to improve consultations for FM. However, to truly improve FM consultations the wider context needs to be considered, such as reaching a consensus between professions on the terminology, legitimacy, classification and likely aetiology of FM.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423623000506

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our patient advisor (JB) for their time and invaluable help discussing the results.

Funding information

Ailish Byrne (Pre-Doctoral Research Fellow, NIHR301986) is funded by the NIHR for this research project. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, NHS or the UK Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests

CVDFC has received honoraries for lectures from the Lloyds Register Foundation and Janssen UK. They have received funding from the EU Horizon programme, NIHR, the BMA and the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development.

Appendix 1 Search strategy

-

1. Family practice

-

2. GP*

-

3. General Practitioner*

-

4. Primary care

-

5. Clinician*

-

6. Doctor*

-

7. Physician*

-

8. Health professional

-

9. Healthcare

-

10. Physio*

-

11. Rheum*

-

12. Medical specialist

-

13. First contact practitioners

-

14. First contact

-

15. First contact physiotherapist

-

16. Musculoskeletal

-

17. Pain clinic

-

18. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17

-

19. Fibromyalgia

-

20. Fibro

-

21. Chronic pain

-

22. 19 or 20 or 21 23.

-

23. Patient

-

24. Patient–doctor relationship

-

25. 23 or 24

-

26. Qualitative

-

27. Mixed Method

-

28. 26 or 27

-

29. Diagnosis

-

30. Treatment*

-

31. Therapy

-

32. Management

-

33. Confidence

-

34. Barrier*

-

35. Facilitator*

-

36. Experience*

-

37. Perspective*

-

38. Opinion*

-

39. 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38

-

40. 18 or 25

-

41. 40 and 22

-

42. 41 and 39

-

43. 42 and 28

Appendix 2 Further study characteristics

Appendix 3 CASP quality assessment

Appendix 4 Author career backgrounds