Introduction

In the last 15 years, several screening routines have been developed worldwide for monitoring metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes among persons with psychosis (De Hert et al., Reference De Hert, Van Winkel, Silic, Van Eyck and Peuskens2010; National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW), 2010; Oud et al., Reference Oud, Schuling, Groenier, Verhaak, Slooff, Deker and Meyboom-de Jong2010; International Diabetes Federation (IDF), 2011). In addition, guidelines have been developed in order to provide interventions to promote healthy lifestyles in the group (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Avripas, Neal and Marcus2005; Lowe and Lubos, Reference Lowe and Lubos2008; Bell et al., Reference Bell, McKenna and Roscoe2009; Porsdal et al., 2010). Persons with psychosis still lack adequate diabetes care (Goldenberg et al., Reference Goldenberg, Kreyenbuhl, Medoff, Dickerson, Wohlheiter, Fang, Brown and Dixon2007), have lower diabetes medication adherence and have difficulties managing diabetes self-care (El-Mallakh, Reference El-Mallakh2006), with increased risk of diabetes complications (Das-Munshi et al., Reference Das-Munshi, Stewart, Ismail, Bebbington, Jenkins and Prince2007) and impaired quality of life (Dickerson et al., Reference Dickerson, Brown, Fang, Goldberg, Kreyenbuhl, Wohlheiter and Dixon2008). Persons with psychosis are nevertheless found to have more contacts with general practitioners than persons with no mental illness (Krein et al., Reference Krein, Bingham and McCarty2006; Oud et al., Reference Oud, Schuling, Groenier, Verhaak, Slooff, Deker and Meyboom-de Jong2010). Some of the explanations for the above-mentioned data are related to loss of contact with reality, inaccurate ideas affecting self-care capability and fear of visiting unknown healthcare staff (Adams, Reference Adams2008). Further difficulties related to the cognitive impairment from which many of these patients often suffer include remembering appointments, adapting lifestyle interventions (Brar et al., Reference Brar, Ganguli, Pandina, Tukoz, Berry and Mahmoud2005; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Avripas, Neal and Marcus2005) and restricted capacity to take responsibility for their own health. In Sweden, specialised treatment for psychosis is given at the county hospital and support in everyday life is provided at home by community psychiatric teams (NBHW, 2003). Diabetes care is performed in primary health care (NBHW, 2010). Thus, diabetes care directed at persons with psychosis is a complex challenge for all healthcare staff, as persons with psychosis and diabetes are managed in different healthcare systems (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The organisation of psychosis care and diabetes care in Sweden. The thick arrows illustrate how information in practice is exchanged according to participants in this study. The thin arrows show information exchange needed in order to achieve optimal diabetes care for persons with psychosis (see SFS, 1982; 1991; 1993; 2001).

Previous research shows that a holistic approach to the person's health, with close follow-ups by psychiatric care in cooperation with diabetes care, may have benefits (Hultsjö and Hjelm, Reference Hultsjö and Hjelm2012). The importance of screening for metabolic risks (Edward et al., Reference Edward, Rasmussen and Munro2010) and performing lifestyle interventions is also highlighted (Chiverton, Reference Chiverton, Lindley, Torteretti and Plum2007; Lowe and Lubos, Reference Lowe and Lubos2008; Forsberg et al., Reference Forsberg, Björkman, Sandman and Sandlund2010). However, no studies were found identifying mental healthcare staff's (MHCS) experience in diabetes care for persons with psychosis and how they integrate this care with psychosis care. This is of interest as diabetes and psychosis are both serious illnesses, and lack of control of either illness may complicate or aggravate one or both (Warren et al., Reference Warren, Crews and Schulte2001). As the situation around persons with psychosis and diabetes is not fully understood, it is warranted to achieve increased knowledge about strategies for nursing performance in order to prevent a diabetes pandemic from arising (Himelhoch et al., Reference Himelhoch, Leith, Goldberg, Kreyenbuhl, Medoff and Dixon2009; WHO, 2009). Failure of diabetes care increases the risk of complications such as injured blood vessels, which can damage the eyes, kidney and nerves and increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases (NBHW, 2010). According to the interaction model of client health behaviours (Pender et al., Reference Pender, Murdaugh and Parsons2006), critical health outcomes depend on the severity of health problems, lack of use of healthcare services and non-adherence to the recommended care regimen. The theory of self-care deficit (Orem, Reference Orem2012) indicates that nursing is required when the individual is incapable or limited in the provision of continuous effective self-care. Restricted capacity to take responsibility for their own health is a threat to self-care (Orem, Reference Orem1991) and adherence to care (Pender et al., Reference Pender, Murdaugh and Parsons2006), which is essential in diabetes care. In order to avoid complications due to failed diabetes care or psychosis care, there could be advantages in exploring MHCS's experiences, as they are often trusted and have regular follow-ups with persons with psychosis at the psychiatric clinic, and thus their attitudes and actions often play an important role for persons with psychosis (Hultsjö and Hjelm, Reference Hultsjö and Hjelm2012). The aim of this study was to explore and analyse MHCS's experiences of diabetes care given to persons with psychosis.

Methods

Design

A qualitative design was used in this study, as the field has not previously been explored. Content analysis is a suitable method for providing comprehensible and detailed illustrations of different participants’ experiences of the same phenomenon (Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff2004). The qualitative semi-structured interview was considered useful in order to reach a deep understanding of the persons’ experiences, attitudes, beliefs and concerns for the future development of care (Patton, Reference Patton2002).

Participants

With permission from the manager of a psychosis outpatient clinic, a meeting was arranged. At the meeting, the principal investigator informed a total of 45 MHCS working in the setting about the study. Saturation guided the study, and thus data collection continued until no new information emerged (Patton, Reference Patton2002). No new data emerged in the analysis after 10 interviews. Two more interviews were conducted in order to ensure the trustworthiness of the categories found. In total, 12 staff members were recruited to participate, consisting of nine nurses, one assistant nurse and two occupational therapists. They were all women in the age range of 38–62 years (median 45), with varying work experience at their present workplace (range 2–14, median 12 years).

Data collection

Data were collected in December 2010. Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted by two psychiatric nurses who were not known to the participants. To achieve a relaxed atmosphere, the participants selected the place for the interviews, which were all held at their workplaces. The interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide (see Table 1). Two test interviews were carried out, leading to minor corrections to the guide (not included in the study). Each interview took 20–60 min in free-flowing discussions. The interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim.

Table 1 The interview guide used in the interviews

DM = diabetes mellitus.

Data analysis

The analysis was guided by qualitative content analysis (Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff2004). After the transcripts were read through for an introduction to the data and to correct any errors in transcription, the data reduction took place. This involved reading data until the most significant statements in the text, the meaning units, with reference to participants’ experiences of diabetes care were identified. The meaning units were condensed to codes in order to find the most central part. The codes were as close to the participants’ statements as possible to avoid interpretation. Codes with similar meaning were grouped and categorised. The categories were compared with each other to find the unique characters of each category. Varying experiences within each category are illustrated as subcategories.

Trustworthiness

To ensure trustworthiness in this study, the interviews were conducted by two research assistants experienced in psychiatric care and in the interview technique used. Data were homogeneous, and after 10 interviews no new themes emerged in the analyses. Two more interviews were conducted to ensure the trustworthiness of the analysis. The results of categories were discussed with a research colleague in order to strengthen the findings (Patton, Reference Patton2002). It is possible that the pre-understanding of the principle investigator analysing data could have influenced the results, but knowledge of the field is also crucial to be able to probe in greater depth into staff's experiences that are brought up and also to understand the concepts described by them.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Linköping University, Sweden, and was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (2008). Thus, the study was performed with written informed consent from all participants. To preserve the confidentiality of data, audio tapes and transcripts were coded by a number, and analysis and presentation of data have been done in such a way that conceals participants’ identity. All collected data are stored such that they are available only to those with access rights.

Findings

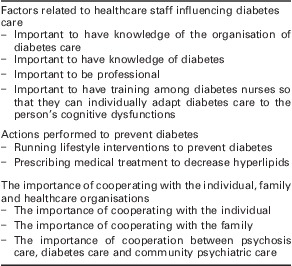

The main results can be presented in three categories: factors related to healthcare staff influencing diabetes care; actions performed to prevent diabetes; and the importance of cooperating with the individual, family and healthcare organisations. The main points of each category are illustrated by anonymous quotations followed by the number of the interview (P5 = Participant no. 5) (Table 2).

Table 2 The categories and their content illustrating mental healthcare staff's knowledge and experiences of diabetes care for persons with psychosis

Factors related to healthcare staff influencing diabetes care

Important to have knowledge of the organisation of diabetes care

Participants in this study felt that they had little insight into diabetes care and therefore found it difficult to have any experiences of this care.

I have no idea how diabetes care works. (P5)

I don't know, maybe they prescribe insulin. (P1)

Those who saw psychosis care as their main responsibility disregarded diabetes care. Some MHCS did not have any intention to become more involved in diabetes care, whereas others described themselves as interested in and active in diabetes care. Those who were more active in diabetes care talked about their own responsibility in the development of diabetes care for persons with psychosis.

Not all of us are involved in diabetes care, only those who are interested. (P6)

Motivation, interest and willingness were seen as important qualities among MHCS to become active in diabetes care.

I believe it is possible to improve the implementation of evidence-based diabetes care for persons with psychosis if we have the motivation and interest. (P4)

Important to have knowledge of diabetes

Difficulties in separating prevention and self-care of diabetes were found among participants. Even those with an interest said they had limited knowledge of the illness and wanted to know more. Those who had attended lectures were positive and felt their knowledge of diabetes had grown, which had increased their motivation to support healthy lifestyles among persons with psychosis in order to prevent diabetes.

I lack knowledge. We started to observe this phenomenon in 2004–2005. We attended a couple of lectures that were good, the interest was aroused. (P2)

Important to be professional

Participants illustrate the importance of being professional, which involved supporting both mental and physical health in a way that is suitable for the patient. If both MHCS and diabetes nurses wanted to collaborate and deliver successful diabetes care, MHCS felt this would be possible.

We referred her there, we called each other, she gave advice, so did I. She got medicines…they discovered increased blood pressure as well. (P1)

It's all about what DHCS you meet. Some of them really want the best for the person and then no problems arise. (P4)

In the interviews it was found positive when diabetes nurses contacted MHCS when planning diabetes care. Other situations describe how MHCS have received chilly comments from the diabetes nurses when doing extra blood controls between the diabetes appointments.

A couple of times I have heard them say, ‘Is it you or is it me who is going to care for their diabetes?’ As if I'm barging into their area. At the same time I find it difficult just to watch when they start to go downhill. (P9)

Statements also illustrate how MHCS experienced some patients having been unprofessionally treated and not taken seriously when referred to diabetes care, which was perceived as unprofessional and affecting diabetes care in a negative manner.

If you know this nurse is working you keep a close watch. You hear from the patient, they don't feel understood and you notice how the patient turns to you with all the questions. (P2)

Important to have training among diabetes nurses so that they can individually adapt diabetes care to the person's cognitive dysfunctions

Diabetes care was not felt to be appropriate for those with psychotic symptoms. Diabetes nurses were considered well educated about diabetes but not trained to deliver diabetes care such that persons with psychosis benefit from it. According to MHCS, only those patients who are mentally stable, and with the ability to heed advice and make their own decisions, were able to follow diabetes recommendations.

For those who manage to go there, diabetes care seems to work fine. They follow recommendations, take their medicines and have pretty good blood controls, but those who lack this ability can't see the seriousness of the illness. Diabetes care is based so much on the patient being able to manage by himself. It's been difficult for our patients, they feel bad on that particular day or they don't have the ability. (P3)

MHCS felt that many persons had difficulties in understanding, managing and acting upon information given by the diabetes nurse. When MHCS asked the patients about their diabetes, they did not understand the seriousness of their illness, nor did they know what to do to get better.

So much information just passes through their minds, when I ask her, everything is fine, there is nothing she can do, but I see the blood results and it's not. They could have given information in a different way. (P8)

Written information was found to be better than verbal information, as persons with psychosis may follow written information without fully understanding the meaning.

Information needs to be more concrete…and written down. (P4)

MHCS said that persons with psychosis do not understand the long-term consequences of their lifestyle, which makes motivation for change more difficult. One nurse described how she follows up the patient on her diabetes appointments in order to help her understand the information and give continual reminders of diabetes recommendations. It was difficult for many persons to understand diabetes recommendations and perform diabetes management in their daily life.

I sometimes accompany her to the diabetes nurse, then I motivate and support her from here, giving her advice about what she can eat. (P12)

It was also felt that many persons missed out on diabetes appointments a couple of times, after which they were no longer called. Being on anti-psychotic medication and intake of sleeping pills was found to make it difficult for many persons to be active and get to the morning appointments that are often offered by diabetes nurses. MHCS stressed how important it is that diabetes nurses take the time to motivate, support and remind persons with psychosis about their appointments and encourage them to be self-confident enough to go there. MHCS were positive towards the yearly diabetes follow-ups and control of eyes and feet in order to avoid complications.

You feel secure knowing they get a yearly check-up, they go through absolutely everything. (P12)

However, they wanted to be informed about appointments so they could motivate persons with psychosis to go.

They should let us know when the appointment is…that way we or staff in community psychiatric care can motivate them to go there. (9)

Problems arose among persons who did not manage to follow appointments or go to the diabetes clinic. In these cases, MHCS felt that one yearly follow-up was not enough. Some MHCS describe how they then did extra blood checks at the psychosis outpatient clinic, whereas others neglect to care for the person's physical health.

Too few follow-ups, then I do extra check-ups of her diabetes. (P10)

Having access to test results from blood samples taken at the diabetes clinic was seen as a helpful tool for MHCS to motivate lifestyle changes among those with difficulties in remembering advice. Some situations illustrate how persons with psychosis in an acute psychotic phase easily forgot diabetes prescriptions. In these cases, healthcare staff describe how they experienced a fast and kind response from diabetes nurses. Some situations reveal how MHCS distributed both anti-psychotic drugs and diabetes medication to persons with psychosis.

The diabetes doctor prescribes the diabetes drugs and I deliver them along with the other medications…it works out better that way, especially when she is very paranoid. (P11)

Actions performed to prevent diabetes

Running lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes

MHCS state that medication given at the psychosis clinic often triggers a longing for sweets and carbohydrates, which in the long run leads to weight gain and obesity. Some staff wondered why persons continued to take the medicines in spite of these side effects. Owing to the weight gain along with their knowledge that persons with psychosis often have difficulties doing exercises, MHCS described how they ran lifestyle interventions at the clinic to prevent physical health problems. They mentioned diabetes but also obesity, hyperlipids, hyperglycaemia and coronary heart attacks. MHCS experience a positive response from those who have attended the groups. One MHCS described how she works individually with persons in need of support to change eating habits or lose weight.

individual training…for those at risk of physical health problems. (P4)

Development of medicines with no weight gain was desired. The lifestyle interventions were mainly directed to persons with no diagnosed diabetes.

Most of them gain weight, they swell up. The best thing is to prevent this. We run lifestyle groups. (P6)

Prescribing medical treatment to decrease hyperlipidaemia

In the interviews, it was highlighted that psychiatrists prescribe medication to decrease hyperlipidaemia. This was positively viewed by some MHCS as lifestyle interventions are difficult for many persons to accomplish but the medicine can decrease hyperlipidaemia and decrease risks of cardiovascular diseases. Others did not see medications as an alternative to lifestyle interventions, and if needed it was the duty of the endocrinologist.

The importance of cooperating with the individual, family and healthcare organisations

The importance of cooperating with the individual

Persons with the ability to understand both illnesses and their interaction were found to have most success in taking care of their health. Those with immediate positive effects from physical activities were more motivated to lifestyle changes. Cooperation was regarded as necessary for optimal care. Difficulties arose when persons wanted to be independent and believed they had the capacity to manage their diabetes all by themselves, but some MHCS had a differing opinion. Some persons wanted to separate their illnesses and only talk to the ones involved in each of the illnesses. Situations illustrate that MHCS sometimes did not know about the person's diabetes and its treatment until after many years. Most MHCS reported that they had to talk very carefully with some persons about their diabetes so as not to infringe on their pride. Nagging too much about a person's lifestyle, giving advice about what to eat and how to perform exercises, could have the opposite effect. Experiences arose that it could feel difficult to support and encourage persons who lacked motivation for diabetes care, even though some MHCS talked about themselves as being ‘extra mothers’ needing to encourage self-care of mental as well as physical health.

She doesn't want me involved in diabetes care, and as it is all about the patient and she doesn't want to, I can't force her. I tried to give her advice but she does the opposite. I see she can't manage the illness but she still believes she does. I'm trapped. (P6)

The importance of cooperating with the family

Cooperating with the family was described as necessary for optimal support of self-care of both illnesses among some MHCS. The family was described as important in supporting the person to adapt to healthy habits and perform diabetes self-care.

The family helps out, supporting her to eat fruit, taking her out for activities. (P3)

However, this was experienced as having to be done with the patient's permission. A few MHCS say that lifestyle is created and performed in a social context including the family and other social relations, and thus they should be involved in this work if possible.

We worked really hard, her parents were active. I said, ‘When you have lost 75 lbs I will take you out for lunch.’ We did go for lunch…it took six years. (P4)

The importance of cooperation between psychosis care, diabetes care and community psychiatric care

Most MHCS illustrate the need of support in daily life in order for person with psychosis to perform diabetes self-care. This support was said to be given by staff working in community psychiatric care. Being seriously committed, and known to the person with psychosis, was seen as good quality among community staff.

If the same person from community psychiatry takes the responsibility and motivates the person to a healthy lifestyle, with good co-operation, you achieve the best success. (P4)

Exchanging knowledge with diabetes nurses was also found to be important, as some of the MHCS then said that they could give advice and repeat information already given. MHCS who had established contacts with the diabetes nurse felt that diabetes care was working out better. Cooperation was seen as important but lacking, and some of the MHCS thought that diabetes care could benefit if it was arranged and delivered by the same health organisation as psychosis care. On the other hand, many of the MHCS expressed that they do not have enough competence to deliver diabetes care.

It's easier if you get the patient's total situation. I don't get the whole picture because the patient is sent here and there. It makes it difficult to keep track. (P3)

It's difficult for the physicians with all different medicines. If we had had the competence it would have been better to perform diabetes care here. (P8)

Cooperation was considered important because both illnesses interact. Most MHCS state that in order for persons with psychosis to feel good they need to be stable in their mental illness and in their diabetes.

Many of our patients are isolated due to the psychosis. They suffer from hallucinations delusions. They develop diabetes and this has a negative impact on their psychosis…other problems arise. (P11)

It was felt that persons unstable in their diabetes had more psychotic symptoms. If they had too strong psychotic symptoms, they were perceived as having more difficulties managing their diabetes. Some MHCS believed that cooperation can increase knowledge about the illness, for them and the patients.

They are not happy with themselves. The diabetes makes them feel physically ill, which affects the psychosis. We have to co-operate. We have the knowledge of the psychotic illness and they know the diabetes. (P5)

Discussion

This study has produced new insights into how MHCS experience diabetes care for persons with psychosis, which has not previously been investigated. It appears that MHCS felt they had limited knowledge of diabetes and the arrangement of diabetes care. Diabetes care was not considered to be individually adjusted to those with cognitive dysfunctions, and diabetes nurses were not trained in caring for persons with psychosis. MHCS with an interest were more active in diabetes care and stressed the importance of running lifestyle interventions because weight gain due to anti-psychotic drugs and inactivity are common among persons with psychosis. Cooperation with the patient, his/her family, diabetes care and community psychiatry was stated to be in need of improvement in order to achieve optimal care for both diseases. Persons who believed they controlled their diabetes were perceived as most difficult to motivate to diabetes care and were seen as having difficulties with diabetes management. Most MHCS felt they had little insight into diabetes care and knew too little about diabetes. This is worrying in view of the high level of medical morbidity and mortality in the group (Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Henderson, Cagliero, Copeland, Louie, Borba, Fan, Freudenreich and Goff2007; Millar, Reference Millar2010). Today, the increased risk of diabetes in the group is well known (Sokal et al., Reference Sokal, Messias, Dickerson, Kreyenbuhl, Brown and Goldberg2004; Robson and Gray, Reference Robson and Gray2006; De Hert et al., Reference De Hert, Van Winkel, Silic, Van Eyck and Peuskens2010). Researchers have drawn up monitoring screening guidelines and routines for blood tests (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Kreyenbuhl, Dickerson, Donner, Brown, Wolheiter, Postrado, Goldberg, Fang, Marano and Messias2004; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Raymondet, Charbonnel and Vaiva2005; Bell et al., Reference Bell, McKenna and Roscoe2009; Edward et al., Reference Edward, Rasmussen and Munro2010; Kessing et al., Reference Kessing, Thomas, Mogensen and Andersen2010). However, the ongoing debate also illustrates the importance of discussing how nursing is performed in the group (Adams, Reference Adams2008; Edward et al., Reference Edward, Rasmussen and Munro2010). It is considered important to highlight and discuss difficulties that MHCS and diabetes nurses face in their daily work. The guidelines for diabetes care (NBHW, 2010) involve a great deal of education and changing lifestyle habits. It is therefore essential that employers offer appropriate education so that healthcare staff are also prepared to care for current health problems among their patients, not only to screen for them.

Most MHCS in this study found it important to run lifestyle programmes. However, their actions were mainly directed at people not diagnosed with diabetes, as those with the diagnosis were viewed as the responsibility of diabetes nurses. On the other hand, diabetes nurses were felt to have limited knowledge of how to adapt diabetes care to persons with cognitive dysfunction. When healthcare staff are not trained to deal with psychotic symptoms, the evaluation and management of these symptoms, as well as the potential to impact engagement in treatment, is problematic. The way a person responds to the illness and treatment is influenced by his/her cognitive processes, symptoms and experiences (Leutwyler et al., Reference Leutwyler, Wallhagen and McKibbin2010).

MHCS in this study describe difficulties among persons with psychosis in performing diabetes care, which is also well documented (Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Henderson, Cagliero, Copeland, Louie, Borba, Fan, Freudenreich and Goff2007; Correll et al., Reference Correll, Druss, Lombardo, O'Gorman, Harnett, Sanders, Alvir and Cuffel2010). Weight gain as a side effect of anti-psychotic drugs was seen as one problem that was well known and somehow acceptable. MHCS experienced more difficulties in motivating those who did not understand the importance of following diabetes care. According to the Swedish Health and Medical Services Act (SFS, 1982:763), care should be given on a voluntary basis. Thus, persons who lack insight into their need for diabetes care cannot be forced to accept care, with increased risk of diabetes complications (IDF, 2011). This may differ between countries, but it highlights how important it is that nurses in different health organisations adopt a holistic approach to a person's health (Llorca, Reference Llorca2008; Sajatovic and Dawson, Reference Sajatovic and Dawson2010). In the United Kingdom, a health screening clinic was developed in order to address the needs of persons with schizophrenia and medical morbidity (Millar, Reference Millar2010). The results show that patients were satisfied with the health checks and improved care and quality of life.

All MHCS in this study thought that collaboration was necessary. Collaboration between diabetes care and psychosis care could further have benefits and give opportunities for staff to exchange knowledge with each other (Krein et al., Reference Krein, Bingham and McCarty2006), which can result in fewer conflicts between different aspects of care. According to Pender et al. (Reference Pender, Murdaugh and Parsons2006), one factor with a negative impact on health promotion is lack of use of healthcare services due to the severity of healthcare problems. MHCS felt that some persons could be overconfident in their capacity to manage diabetes care, but continue with unhealthy habits and miss appointments. Self-efficacy is the assessment of personal capability to organise and carry out a particular course of action such as healthy lifestyle activities, but is not concerned with the actual personal skill one has but with the judgement of what one can do with whatever skills one possesses. Perceptions of competence in a particular area motivate individuals to engage in those behaviours in which they excel. In this study, an inaccurate appraisal of self-efficacy can be viewed as an obstacle in diabetes care. From a nursing perspective, this can be viewed as a risk factor in the performance of self-care (Orem, Reference Orem1991). It also shows the importance of patient education being targeted towards accurate assessment of self-efficacy beliefs and correcting any misperceptions about the patient's confidence in being able to perform self-care individually or in a group.

It is also important that nurses be aware that poor mental functioning causes suffering and may interfere with diabetes self-care (Edward et al., Reference Edward, Rasmussen and Munro2010). Among persons with diabetes, it is found that those with co-morbid mental illness estimate their own quality of life as lower than others (Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Scheidt-Nave and Baumeister2009). It is therefore important to raise the importance of the prospects highlighted by MHCS of developing cooperation among those involved in the patients’ care. Humans cannot be divided into soul and body (Wiklund, Reference Wiklund2011), but in this study diabetes care was seen as suitable only for those with no psychotic symptoms. This is a complex challenge as psychotic symptoms interact and restrict the capacity to perform self-care (Orem, Reference Orem1991). One way to improve the situation is to have a common health promotion practice, but this is not yet the case (DiClemente et al., Reference DiClemente, Crosby and Kegler2009). If a theory is tested in practice-based contexts, this use of theory can help healthcare staff to understand why people behave the way they do, to identify mediating variables or targets of change and suggest effective strategies for changing behaviour. Individual responsibility and community involvement in all areas of health promotion are still essential to the health of our nations. Nurses are the healthcare professionals best suited to meet the challenges of the healthcare environment (Maville and Huerta, Reference Maville and Huerta2008).

Some limitations with the study need to be mentioned. All participants were recruited from the same district, which could have consequences for the generalisability of the results. To help the reader decide whether the results are transferable to other contexts, the organisation of psychosis care and diabetes care in Sweden is described. Persons with psychosis are known to have difficulties with diabetes care (Goldenberg et al., Reference Goldenberg, Kreyenbuhl, Medoff, Dickerson, Wohlheiter, Fang, Brown and Dixon2007), which is why increased knowledge is warranted. The qualitative content analysis is the attribute of data that do stand in place of phenomena that are distinct and real. What reality is cannot be divorced from how it is described (Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff2004).

Conclusion and implications

Psychiatric nurses found a lack of diabetes knowledge, whereas diabetes nurses were perceived as not trained to adjust diabetes care to persons with cognitive dysfunctions. This indicates that health employers in both settings need to provide knowledge in their working teams about how poor mental functioning may interfere with diabetes care. One suggestion is to organise workshops in which nurses from different settings can discuss and exchange knowledge with each other. The physical health of those with diabetes was seen as the responsibility of diabetes nurses. Simultaneously, diabetes care was seen as suitable only for those who were able to follow diabetes recommendations. Those with psychotic symptoms and an inaccurate appraisal of self-efficacy, who believed they had the capacity to manage their diabetes despite MHCS judgements, were seen as most difficult to motivate to diabetes care. The findings emphasise the need for integration of medical and psychiatric services among those patients. Benefits could be achieved if nurses from both services together with the patient and his/her family develop common care plans including the whole health situation. The family is important as they can help identify targets of change, suggest effective strategies for changing behaviour and be supportive in this process. Owing to the illness, it is crucial that these care plans are individually adapted, and if this is not enough the patient's cognitive impairment may need to be addressed. This can help the patient to understand how different health problems interact with each other, and the importance of caring for the whole body. Nurses are the healthcare professionals best suited to develop nursing education and nursing practice. Suggestions for development in education on all levels need to better highlight how mental illness can interfere with the individual's ability to care for physical health. This is important as all healthcare professionals will meet these patients in different healthcare settings in their future profession.

Acknowledgements

The study was performed with grants from the Psychiatric Clinic, Ryhov County Hospital, Jönköping, Sweden and Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden. Sally Hultsjö was responsible for the study design, the concept, the analysis and the writing of the paper. Maria Karlsson and Anette Bergström conducted the interviews.