Introduction

Family practice strives toward a medical model where people are at the centre of health care (EURACT, 2011). The challenge is not only focusing on the disease but recognizing the health problems and needs expressed by the person (Starfield, Reference Starfield2009; Reference Starfield2011). The integration of personal context in clinical decision-making improves follow up, health outcomes and reduces diagnostic costs (Di Blasi et al., Reference Di Blasi, Harkness, Ernst, Georgiou and Kleijnen2001; Stewart, Reference Stewart2003; Starfield, Reference Starfield2009; Reference Starfield2011; Bertakis and Azari, Reference Bertakis and Azari2011; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Ryan and Bodea2011; Weiner et al., Reference Weiner, Schwartz, Sharma, Binns-Calvey, Ashley, Kelly, Dayal, PATEL, Weaver and Harris2013; Schrans et al., Reference Schrans, Avonts, Christiaens, Willems, De Smet, Van Boven, Boeckxstaens and Kühlein2016). The unique ability of family practice to accumulate knowledge, both medical and contextual, over time in a continuous relationship makes it possible to give care in a person-focused way (Starfield, Reference Starfield2011).

Many people have symptoms or feel ill, but only some of them actually contact a health care provider (White et al., Reference White, Williams and Greenberg1961; Green et al., Reference Green, Fryer, Yawn, Lanier and Dovey2001; Stewart and Ryan, Reference Stewart and Ryan2015).

Contacting a family physician (FP) will generally be preceded by a complex thinking process (Cassell, Reference Cassell2004). This decision process is reflected in one or more ‘reasons for encounter’ (RFE), including not only the presenting symptom or request but also the meaning, interpretation or belief the person attaches to it (Cassell, Reference Cassell1985; Hartman et al., Reference Hartman, Van Ravesteijn, Lucassen, Van Boven, Van Weel-Baumgarten and Van Weel2011).

The concept of RFE is integrated in the International Classification of Primary Care, version 2 (ICPC-2) (WONCA, 2005; Verbeke et al., Reference Verbeke, Schrans, Deroose and De Maeseneer2006), allowing it to be documented in a structured way and making it available for clinical care and research (Hartman et al., Reference Hartman, Van Ravesteijn, Lucassen, Van Boven, Van Weel-Baumgarten and Van Weel2011). FPs are trained to clarify the RFE in order to tailor their clinical decision in an individualized, person-focused way (Deveugele et al., Reference Deveugele, Derese, Maesschalck, Willems, Driel and Maeseneer2005). One of the strategies to disentangle the RFE is to elicit the ideas, concerns and expectations (ICE) a person has regarding the symptoms he is feeling, the illness he experiences or the social issues he has. Exploring the ICE within or behind the RFE is one way to take the patient’s preferences and values into account, one of the three cornerstones of evidence-based medicine (Sackett, Reference Sackett1995). In a former study, we described the ICE as one of the classes of person-related information (Schrans et al., Reference Schrans, Avonts, Christiaens, Willems, De Smet, Van Boven, Boeckxstaens and Kühlein2016). Registering ICE in a classified way, using ICPC-2, would not only be interesting for clinical care but also for research purposes and will make ICPC-2, as a classification, more person focused.

This study aims to explore the extent to which the ICE behind the RFE can be classified in ICPC-2 and what additions to ICPC would be needed to be able to classify all identified ICE.

Methods

Setting and data collection

This paper is based on the analysis of data from an earlier study. In the former study, FP trainees affiliated with Ghent University collected data on 613 consultations in 36 GP teaching practices during one day in 2005 (Matthys et al., Reference Matthys, Elwyn, Van Nuland, Van Maele, De Sutter, De Meyere and Deveugele2009). All GP trainees (n=39) had been instructed and trained to observe and narratively record the patient’s ICE as expressed during practice consultations or home visits.

Additional information about patient characteristics, the RFE, the diagnosis and consultation details were also collected by the trainees. The RFE and diagnoses are not part of this study because it is known that they can be classified with ICPC-2.

Classification of free text into codes

First, all registered ICE within the 613 consultations, even if no RFE was noted but an ICE was mentioned in a later stage of the consultation, were classified into ICPC-2 codes by a junior and senior researcher (T.C. and D.S.) independently. Subsequently, different coding outcomes were discussed until consensus was reached. Classification was based upon the operational definition of ICE from the instructions given to the data collectors in the study by Matthys et al. (Reference Matthys, Elwyn, Van Nuland, Van Maele, De Sutter, De Meyere and Deveugele2009):

-

∙ Ideas: the ideas the patient has about a possible diagnosis, treatment or prognosis expressed in the consultation.

-

∙ Concerns: the concern the patient has about a possible diagnosis or therapy expressed in the consultation.

-

∙ Expectations: the expectation for a treatment, a diagnosis or a therapy expressed in the consultation.

If no ICPC-2 code seemed appropriate, it was labeled with ‘no coding possible’ (NCP).

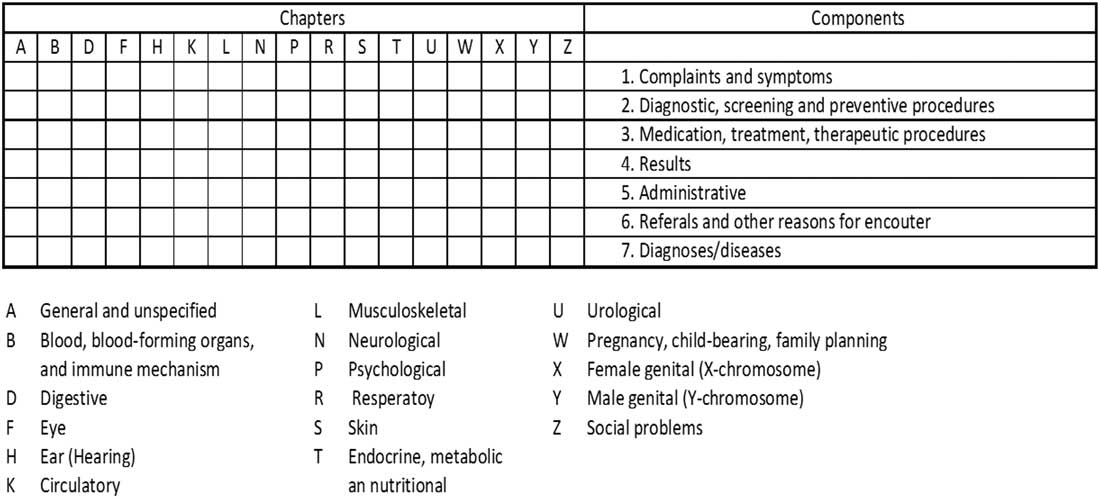

To understand the coding process, it is important to keep the structure of ICPC-2 in mind (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Bi-axial International Classification of Primary Care, version 2 structure

ICPC is based on a simple bi-axial structure; it was designed to make paper-based collection of data possible. One axis refers to the 17 chapters mainly based on body systems, each with an α-code. The other axis includes seven ‘identical components’ with rubrics bearing a two-digit numeric code. Component 1 provides rubrics for symptoms and complaints (numbers 01-29). Component 7 is the diagnosis/disease component in each chapter (numbers 70-99). Components 1 and 7 in ICPC-2 function independently in each chapter and either can be used to code patient RFEs, presenting symptoms and diagnoses or problems that are managed. Components 2–6 (process of care and intervention codes) are common throughout all chapters, and each rubric is equally applied to any body system (WONCA, 2005; Verbeke et al., Reference Verbeke, Schrans, Deroose and De Maeseneer2006).

Some examples of ICPC-2 codes include R05 cough; T11 dehydration; R24 haemoptysis; A03 fever; P18 medication abuse; Z01 poverty/financial problem; Z06 unemployment problem; D92 diverticular disease; R74 upper respiratory infection, acute; S70 Herpes zoster; A72 chickenpox; P76 depressive disorder; -34 blood test; -44 preventive immunization/medications; and -67 referral to physician/specialist/clinic/hospital.

Also see the online supplementary material file for all ICPC-2 codes (WONCA).

Analysing ICE with a NCP label

The NCP labels were analysed separately in a qualitative way. Two researchers inductively and independently created other new categories. In a process of discussion and agreement, consensus was reached on new categories that allowed the classification of non-codable items (Lincoln and Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985).

Results

The involved patients had a mean age of 48.5 years (range 18–91 years). Slightly more patients were female (55.5%), and about one-third (35%) had completed higher education. More than half (57%) of the patients had consulted with a FP at least four times in the year prior to the registration day. Two-thirds (67%) consulted with a new problem, and 16% of the registrations were home visits.

ICE

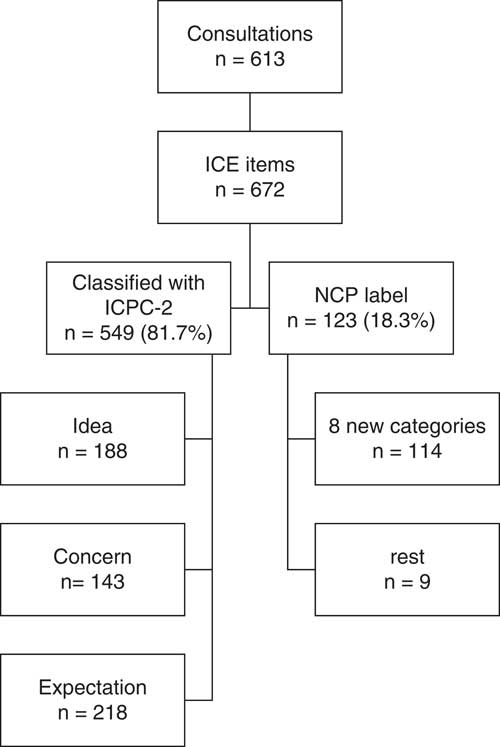

During the 613 consultations, 672 ICE items were narratively registered. Figure 2 shows a summary of the results.

Figure 2 Summary of the results. ICPC-2=International Classification of Primary Care, version 2; NPC = no coding possible.

Of the 672 ICE items, 549 (81.7%) could be classified directly in ICPC-2, 34.2% were ideas, 26.0% were concerns and 39.7% expectations. Table 1 shows how the ICE codes are distributed in the ICPC-2 chapters and components.

Table 1 Distribution of ideas, concerns and expectations (ICE) in the international classification of primary care, version 2 (ICPC-2) components/chapters

Of the 331 ideas and concerns classified by the ICPC-2 chapter, 22% were classified in the general and unspecified Chapter A, 15.7% in the Respiratory Chapter (R) and 12.1% in the Musculoskeletal Chapter (L), together accounting for about half of all the ideas and concerns that are classifiable in ICPC-2.

All expectations classified in ICPC-2 are within components 2–6, the process of care and intervention codes. No specific chapter was given to these codes as they are identical in every chapter.

About one-fifth (18.3% or 123 out of 672) of the registered ICE received a NCP label because they could not be coded directly with ICPC-2.

In total, 114 NCP-entries could be attributed to one of following eight new categories; four applied to concerns and four to expectations. None had to be created for ideas, suggesting that ICPC-2 covers this area sufficiently.

-

∙ Concern about the duration/time frame

-

∙ Concern about the evolution/severity

-

∙ Concern of being contagious or a danger to others

-

∙ Patient has no concern, but others do

-

∙ Expects a confirmation of something

-

∙ Expects a solution for the symptoms without specification of what it should be

-

∙ Expects a specific procedure

-

∙ Expects that something is not done

Remaining nine text labels were too non-specific to make any classification possible. Table 2 summarizes these findings and gives exemplary quotes.

Table 2 Ideas, concerns and expectations (ICE) NCP, categories and examples

ICPC-2=International Classification of Primary Care, version 2.

Discussion

Summary

A total of 613 patient contacts resulted in 672 registered ICE, of which 81.7% could be coded directly with ICPC-2. The addition of eight new categories would allow classification of almost all the NCP-labeled entries.

Strength and limitations

This study is based on a relatively small set of data that was registered in one day in 36 practices. The sample is localized in the northern part of Flanders, Belgium. These are both limitations. Nevertheless, this is a first attempt to classify ICE with ICPC-2 and gives directions in the development of ICPC to make it more person-focused.

Implication for research and practice

Our most important result is that most ICE can be coded with ICPC-2. Only eight new categories have to be added to ICPC-2 to capture all ICE. ICPC-2 has already systematically integrated the possibility of coding ‘fear of.’ This always concerns a specific disease or a group of diseases, but does not take the fear of severity or the duration of a symptom into account; therefore, it is not surprising that we found new categories on that subject. All expectations that could be coded with ICPC-2 are requests to do something such as a blood test, a prescription or a referral. The four new categories make it possible to capture the persons’ expectations in a broader sense.

In a number of morbidity registrations in primary care, the RFE is already registered (Soler et al., Reference Soler, Okkes, Oskam, Van Boven, Zivotic, Jevtic, Dobbs and Lamberts2012; Britt et al., Reference Britt, Miller, Henderson, Bayram, Valenti, Harrison, Pan, Wong, Charles, Chambers, Gordon and Pollack2014). The incorporation of the RFE in the analysis of the outcome of the care is important (Hartman et al., Reference Hartman, Van Ravesteijn, Lucassen, Van Boven, Van Weel-Baumgarten and Van Weel2011). Classifying additional ICE may lead to further clarification and improved understanding of the RFE (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Brown, Donner, Mcwhinney, Oates, Weston and Jordan2000; Hartman et al., Reference Hartman, Van Ravesteijn, Lucassen, Van Boven, Van Weel-Baumgarten and Van Weel2011); adding essential information for clinical use in the EMR brings the needs of persons to a population level for scientific analysis in order to stimulate change toward a medical model where ‘disease’ is no longer the primary focus (Soler and Okkes, Reference Soler and Okkes2012). It might even be helpful in bridging the gap between the patients’ narrative and the FPs’ medical discourse (Sheaff et al., Reference Sheaff, Halliday, Byng, Ovretveit, Exworthy, Peckham and Asthana2017).

Conclusion

Classifying ICE with ICPC-2 is feasible; only eight categories must be added to capture all ICE. This is an important step forward to develop ICPC in a person-focused care context. We will continue our research to make personal needs and preferences available for both clinical care and research purposes and to develop ways to register and classify it in primary care.

Acknowledgments

Diego Schrans, Pauline Boeckxstaens and Thomas Kühlein are members of the Wonca International Classification Committee (WICC). The WICC played an important role in the development of this article because the idea arose during a working meeting in Amsterdam. We would also like to thank the GP trainees and teaching practices for collecting the data. Many thanks to JM for providing the data for further analysing.

Financial Support

No external funding was received.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The study was approved by the ethics committee from the University Hospital Ghent (reg. number: B670201317041).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://www.kith.no/upload/2705/icpc-2-english.pdf