Introduction

On 5th July 1948, the National Health Service (NHS) was established to provide health care for all citizens independent of sex, age, creed or wealth (NHS, 2009). Since the creation of the NHS, several reforms have occurred but the earliest principle of closing the gap of inequalities in health care by providing for those most in need has remained. In 1971, Tudor Hart discussed the Inverse Care Law ‘that those in most need of care and those less likely to receive it’ (Tudor Hart, Reference Tudor Hart1971). To this day, the Inverse Care Law remains true when the oral health needs of the homeless population are addressed.

Definition of homelessness

Homelessness is difficult to define, with agencies applying differing definitions (Anderson and Christian, Reference Anderson and Christian2003). These variations affect the numbers recorded as homeless in official surveys. In addition, there are a number of people who are homeless, but living with friends or staying in temporary accommodation. This group is referred to as the hidden homeless. They are by definition excluded when statistics are being gathered, affecting the accuracy of estimates of the population. Fitzpatrick et al. (Reference Fitzpatrick, Kemp and Klinker2000) took a common sense approach to defining homelessness as follows:

a) rooflessness

b) living in emergency/temporary accommodation

c) living long term in institution

d) bed and breakfast

e) informal/insecure/impermanent accommodation with a friend

f) intolerable physical conditions

g) involuntary sharing (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Kemp and Klinker2000).

Research on the causes of homelessness has been linked directly and indirectly to policy in the United Kingdom, a notion that has led to lively debate about theorizing on homelessness in Britain. Neale (Reference Neale1995) explored the potential of a number of theoretical perspectives (feminism, post-structuralism, post-modernism, structuralism and critical theory; Neale, Reference Neale1995; Collins and Freeman, Reference Collins and Freeman2006) for increasing our understanding of homelessness, because she and other critics (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick, Kemp and Klinker2000) argued that simply estimating the number of homeless people was not sufficient guide for researchers or to help with theoretical development about the causes of the homelessness.

Drug abuse is an important factor that leads to poorer health. Up to 56% of homeless population were reported to frequently abuse alcohol (Harrison and Carr-Hill, Reference Harrison and Carr-Hill1992). Alcohol abuse has a detrimental effect on the body causing high blood pressure, vitamin deficiencies and liver cirrhosis. In the oral cavity, chronic and prolonged consumption of alcohol when combined with tobacco has a synergistic effect increasing the risk of oral cancer by 15 times (Oral Cancer Foundation, 2001–2010). Tobacco alone has a detrimental effect on the oral tissues predisposing to leukoplakia, gingivitis, periodontitis and stomatitis (Johnson and Bain, Reference Johnson and Bain2000). Abuse of illegal drugs is reported to be high particular amongst the homeless under 25’s group with 95% reporting use of drugs. Of this number 94% have used cannabis, 38% crack cocaine and 43% heroin, whereas in comparison in the general population only 4% have used crack cocaine or heroin (Wincup et al., Reference Wincup, Buckland and Bayliss2003). Use of these drugs can cause gingival necrosis, dental erosion, leukoplakia, oral cancer, nasal septum and palatal perforation. Drug dependency can often influence their lifestyles and decisions making them unreliable attendees at dental appointments.

Health inequalities among the homeless can also be attributed to mental health problems. It has been estimated that between 30 and 50% of the homeless suffer with mental health problems (Marshall, Reference Marshall1996) although data varies with reported levels being eight times higher than the general population for those living in hostels and 11 times higher for rough sleepers (Bines, Reference Bines1997). The majority of mental health problems are depression and anxiety which can directly impact on an individual’s ability to acquire and complete course of dental care. This is because when depressed health issues take a lower priority and anxiety can be exaggerated by visiting health professionals including dentists.

Furthermore, inadequate housing, exposure to the elements and contact with communicable diseases further exacerbates health problems, such as skin rashes, leg ulcers, musculoskeletal complaints and respiratory problems, in particular Tuberculosis, which is 200 times higher than in the general population (St Mungos, 2007).

In December 2003, the British Dental Association (BDA) produced a discussion paper detailing the current issues surrounding dental care for the homeless (Harrison and Carr-Hill, Reference Harrison and Carr-Hill1992).

The BDA highlights four key areas in which there is a lack of research, these include the:

1) The oral and dental health of the homeless

2) The use of emergency services for the acquisition of dental care

3) The occupational health issues of dentists treating the homeless

4) The most appropriate method of delivering dental care (BDA, 2004).

The General Dental Services (GDS) is the main provider of dental care in the United Kingdom, however this may not be the best method of delivering oral health care. It is accepted that health provision ‘frequently fails to acknowledge the needs of this extremely vulnerable group (Bruce, Reference Bruce2000).

From a dental perspective, lacking a permanent address often excludes the homeless from registering with a dentist, attending for appointments and having the finance to pay the NHS charges. Furthermore, due to their chaotic lifestyles (DoH, 2005) the homeless have poor personal hygiene which leads many General Dental Practitioners to refuse to provide treatment. In addition, oral health is further compounded by lack of awareness, limited access to oral hygiene devices, low perceived need and exclusion from medicals services due to a fear of excessive need (Fisher and Collins, Reference Fisher and Collins1993).

The General Dental Services are currently the main route of accessing dental care in the United Kingdom for the majority of the population, however due to the reasons stated previously this may not be the best method of delivering oral health care. It is accepted that health provision ‘frequently fails to acknowledge the needs to this extremely vulnerable group (Bruce, Reference Bruce2000). As a result, services are required to reduce the barriers to care and make it easier for the homeless to access dentistry by being flexible, reassuring and allowing quick access (Bruce, Reference Bruce2000).

The BDA recognises that services for the homeless often need to be free, flexible and multidisciplinary with other areas of health care. There are several models of healthcare provision for homeless people:

• Mainstream NHS service (dedicated time or specialists workers)

• Dedicated NHS services – comprehensive and facilitator service (full range of primary care, with healthcare workers helping them to access other healthcare services).

As a result there are currently several mobile and fixed clinics running in the UK which have good connections with homeless shelters in the local areas, along with charitable care provided by volunteers over the Christmas period (BDJ[update article], 2006). However, despite the provision in other areas of the UK, Birmingham does not have a dedicated service for the homeless.

Hence, the aim was to assess the oral health needs of homeless people in specialist units in London, Cardiff, Glasgow and Birmingham in order to allow recommendations for service delivery for this socially excluded group to be made.

Methodology

The sample selection

Opportunity sampling was used for homeless participants, which consist of taking the sample from people who are available at the time the study is conducted and satisfy the criteria. The selection criteria for homeless adults in this study in line with ethical guidelines were all participants had to be over 18 years of age, should be currently homeless and not suffering from any mental health problems that may affect their ability to consent.

All staff working at the specialists units were sent a letter of invitation detailing the reason for the research and inviting them to take part, followed by an indepth information sheet detailing how the research was organised, ethical approval, the benefits and disadvantages and confidentiality of information. Written consent was obtained. The sample was made up of dentists, dental care professionals and nurses who indicated a willingness to take part in the study.

Design of the questionnaires

The questionnaire: homeless people

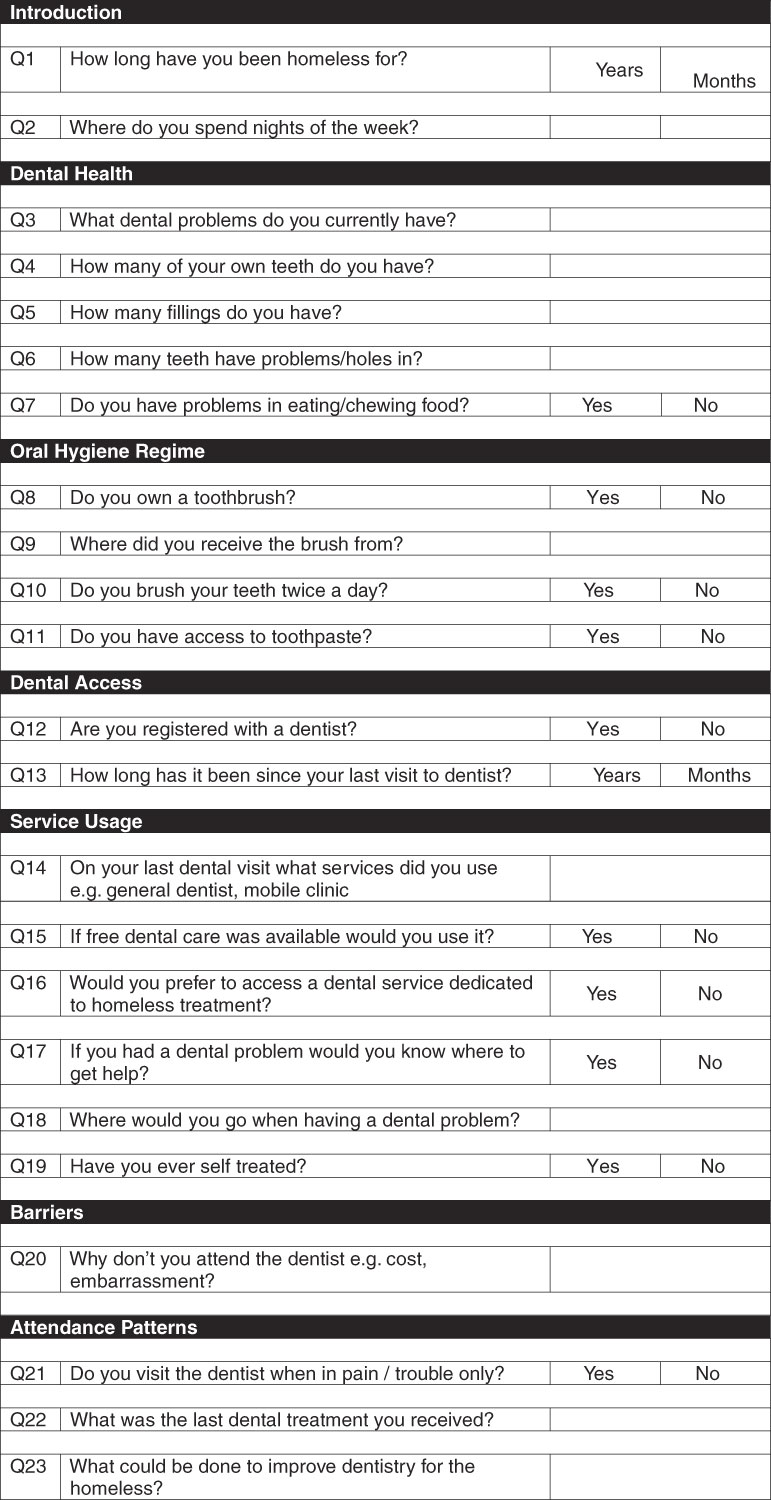

This consisted of a series of questions, including questions about the participant’s medical history, their reasons for homelessness and substance abuse (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Questionnaire/interview – homeless participants

The questionnaire: dental staff

The questionnaire was organised into five areas. Section 1 was an introduction, Section 2 related to attitudes of other dental professionals to working with the homeless and Section 3 was about treatments performed. Section 4 was inquiring about patient related issues and Section 5 was the future of homeless dentistry (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Questionnaire/interview – dental staff participants

Figure 2 Continued

Administration of the questionnaire

Both questionnaires were piloted on an equivalent group. The participants (staff and homeless people) were asked to complete the questionnaire. Many of the homeless adults required assistance to complete the questionnaire due to poor eyesight and/or poor literacy skills.

Statistical analysis

The data were coded and entered onto a computer using SPSS version 12. Open-ended questions were coded by grading answers into several categories. The qualitative aspect of the questionnaire was analysed using (Q20 for homeless participants on ‘Why do you not attend the dentist?’) A framework approach to data analysis was adopted in the manner suggested by Pope et al. (Reference Pope, Ziebland and Mays1999). A preliminary framework based on the research questions was developed. The transcripts were then read and, following familiarisation with the data, the initial framework was expanded to reflect themes emerging from the interviews. The data were next indexed according to the framework and further refined. To guard against bias, in accordance with the methodology described by Pope et al. (Reference Pope, Ziebland and Mays1999), the transcripts were analysed independently by another researcher. Subsequently, consensus was achieved on emergent themes and issues.

Ethical approval

This study received ethical approval from NHS Research Ethics Committee COREC Oxfordshire B (Ref: 07/H0605/74).

Results

Sample

Seventeen staff working in homeless dentistry completed questionnaires. Of these, nine were dentists, seven were nurses and one was a therapist. All staff who were contacted, completed the questionnaire, which gave a 100% response rate, from dentists working in specialist units in London, Cardiff, Glasgow and Birmingham. Twenty-seven homeless adults took part in the interview. Of these, 22 were under active treatment at a homeless dental clinic and the remaining five were from the Birmingham homeless shelter who were not receiving dental care. The majority of homeless adults who met the criteria for inclusion completed an interview, only two adults declined to be involved in the study. The following themes emerged from the qualitative aspect of the questionnaire, these being dental health; service development; and barriers to dental treatment for homeless people (the quotes are coded as either patient or dentist).

Demographic profile of homeless adults

In all, 87% of the sample was male. The ages of participants ranged from 23 to 61 years. Eighty-four percent of the samples were Caucasian, 9% were Asian and 7% were Black. The mean patient demographic was Caucasian male aged 36–45 years. Most patients had good communication skills.

The time period of homelessness was on average five years but varied widely; of which just fewer than half or respondents resided in hostels, around 25% lived on the streets with a small percentage living in temporary accommodation.

Questionnaire: homeless participants

Dental health

The majority of participants were reported having poor dental health. Dental pain was reported with ‘difficulties in eating and talking’ (patient). The main reason for attendance at the dental clinics was dental pain (94%), followed by missing teeth (41%), 12% swelling and 18% periodontal problems. Forty-five percent of homeless participants stated that they only attended dental clinics when in pain and did not attend the dentist regularly. Reasons for poor attendance as shown in Figure 3 were mainly financial issues, the low priority they placed on dental care and also fear.

Figure 3 Reasons for non-attendance

Oral health products

Ninety-five percent of patients owned a toothbrush and 91% had access to toothpaste. Fifty-nine percent of patients reported brushing their teeth twice daily at the dental clinics; this figure was 20% among the residents of the Birmingham hostel.

Reported service usage

Homeless participants reported poor access to dental care with only 23% of patients registered with a GDP. None of the participants reported the use of the hospital emergency services. All participants reported that they knew where to obtain dental care if in pain, and 90% identified the homeless dental clinics. However, the residents at the Birmingham shelter stated ‘they would not know where to obtain emergency dental care’ (patient).

Questionnaire: staff

Attitudes of other professionals

When asked about the attitudes of other dental professionals to working with the homeless all the participants identified negative attitudes with reports of a fear of aggression and cross infection concerns. All participants stated they would recommend working with the homeless to others within their profession as they found the work rewarding due to ‘helping those in need’ and ‘relieving pain’ (dentist). The least rewarding aspects were being unable to complete treatment and missed appointments.

Service arrangements and occupational health

The number of patients seen per day ranged from 10 to 15. Eighty-eight percent of patients had treatment plans constructed, however only half of patients attended for follow-up. The majority of dental staff felt a combination of emergency treatments and treating planning was suitable. The occupational health effect of working with the homeless was not found to be significant. However, only one participant had suffered work-related stress. Staff reported good referral connections/services and felt they had a good support network. Violence within the homeless service was not found to be higher than the GDS although 53% had experienced some form of aggression during their work. The main differences between working with the homeless and in GDP was reported to be poor levels of attendance, poorer general health and treatment being more patient led.

Health

The level of dental need was assessed by dentists to be high. Dentists reported that ‘the average number of teeth remaining was 20 although there was a broad range from 2 to 30’ (Dentist)’.

Reported type of work performed in homeless clinics

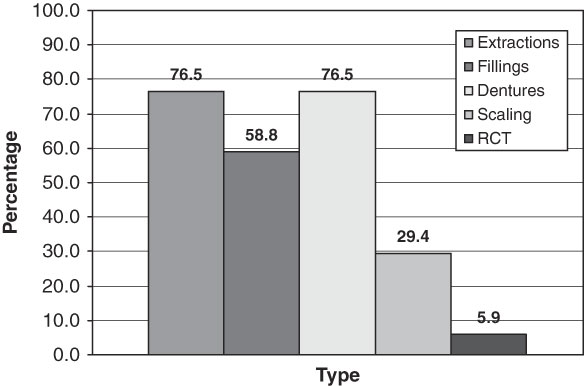

The majority of dental treatment performed in the homeless dental sector were extractions and dentures (as shown in Figure 4) and this correlates with the reported poor oral health.

Figure 4 Type of work performed in homeless clinics

Service use

As to the future of homeless dentistry, the majority of staff advocated the use of dedicated homeless dental clinics for treatment. Reported reasons were patients not being welcome in the GDS and an inability to cater for the patient’s special needs. Dental staff stated that improvements had been made to the dental service, since they had been working there, although the majority indicated that further changes were necessary. The improvements specified included increased availability with additional days of opening and the need for a fixed site clinic. It was reported that over 70% of homeless patients had no issues and were happy with the treatment they received.

Discussion

Oral health among the homeless was reported by dental staff to be poor at the first appointment, which is confirmed by the mean number of 20 teeth remaining and 32% of patients reporting dental pain. These figures are worrying as the absence of pain and being able to eat are necessities in life and can impact greatly on a person’s health. Poor dental health is also illustrated by the type of dental treatments performed with 77% of dentists indicating that extractions and dentures were the main courses of treatment. As might be expected, this group of homeless people had a greater experience of dental caries compared to the Adult Dental Health Survey (1998; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Steele, Nuttall, Bradnock, Morris, Nunn, Pine, Pitts, Treasure and White2000). Dentists reported that homeless patients had a greater numbers of missing and decayed teeth, but a lower number of filled teeth. Suggesting that there are high levels of unmet restorative need and the absence of successful oral hygiene regimes in the homeless population (Collins and Freeman, Reference Collins and Freeman2006).

The poor oral health of the participants is linked to poor attendance with 45% being irregular attendees and missing appointments. It is also linked to poor oral hygiene as despite nearly all patients owning a toothbrush only 60% brushed their teeth on a twice-daily basis. Diet is most probably a risk factor despite patients not admitting to having a high-sugar diet, it is likely that processed food which is low cost and easily acquired plays an important role.

Access to dental care was poor among the homeless with only 22% registered with a GDP and there being an average of three years since their last visit. Eighty-eight percent of dental staff reported that patients have difficulty accessing routine dental care in a GDP. The majority of patients visiting the dedicated homeless dental clinics, in London, Cardiff and Glasgow, knew where to obtain dental care. However, the opposite was found among the residents interviewed at a Birmingham hostel. This may indicate that because Birmingham does not have a specialist homeless unit, homeless adults are less likely to receive dental care. The use of emergency services was reported by dental staff to be high, however this was not found among the homeless participants of whom none had used accident and emergency department. The barriers to access were reported to be cost, a low priority being placed on dental care and dental anxiety.

The experience of working with the homeless was reported to be good with all dentists recommending the career to others. The majority of staff had not experienced any violence although aggression was found to be higher among the homeless.

In terms of the homeless dental services, the majority of patients were happy with the level of care they received and could not think of any improvements. Surprisingly, 45% of patients reported they would rather be treated by a General Dental Practitioner than at a dedicated homeless service, which may indicate their desire to reduce their segregation from society.

After contacting the Birmingham City Council directly, it was found that a homeless dental service runs one day a month at the Salvation Army William Booth Centre in Birmingham. If treatment cannot be provided at the clinic, an appointment is made for the patient at a local dental clinic. It is notable that this information is not widely publicised and is not available on the Birmingham homeless health pages. This may also explain why homeless adults at other shelters in Birmingham are unaware of the service and were unable to obtain dental care.

Conclusion

This study found some evidence that the oral and dental health of homeless adults is poor with a high level of need for dental treatment. The service use of the homeless is low, with low levels of registration with a GDP, although emergency service use has been previously been overreported. Occupational health issues among dentists were low with a low incidence of aggression. Only one dentist had experienced stress and good support networks were provided. In terms of the most suitable method of treatment, staff felt a dedicated homeless service was most appropriate, whereas there was almost an equal split of patients advocating the GDS or the dedicated dental clinics. It seems there is not a definitive method of delivering care to the homeless. Therefore, the service delivery message is that there should be dental services available that are dedicated to the homeless, whereas local family General Dental Practitioners should adapt to provide care to some of those most vulnerable, thereby aiding their rehabilitation and integration back into society. This method of having flexible services means all homeless participants can potentially find a method that delivers dentistry, is a suitable way, and will increase uptake of dental care. There are a number of limitations to this study: 1) the sample size is small, due the number of dental professionals working in specialist homeless units; 2) the sample of homeless people is not representative; and 3) the study lacks reliability in terms of repeatability.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the dental staff across the United Kingdom and homeless patients who participated in the research.