Introduction

After low back pain, the knee is the second most common site for musculoskeletal pain in adulthood in the United Kingdom (Urwin et al., Reference Urwin, Symmons, Allison, Brammah, Busby, Roxby, Simmons and Williams1998; McAlindon, Reference McAlindon1999; Peat et al., Reference Peat, McCarney and Croft2001). Patellofemoral joint (PFJ) disorders, presenting as anterior knee pain (AKP), are recognised to be a major component of knee pain cases seen in sports injury and orthopaedic outpatient clinics (Devereaux and Lachmann, Reference Devereaux and Lachmann1984; Stanitski, Reference Stanitski1993; Luhmann et al., Reference Luhmann, Schoenecker, Dobbs and Eric2008), and specialists from these fields consider there to be many different treatments that are specific to the particular causes of patellofemoral pain (Juhn, Reference Juhn1999; Fulkerson et al., Reference Fulkerson, Buuck, Dye, Farr and Post2004; Post, Reference Post2005; Witvrouw et al., Reference Witvrouw, Werner, Mikkelsen, Van Tiggelen, Vanden Berghe and Cerulli2005; Fagan and Delahunt, Reference Fagan and Delahunt2008). Yet, there is an almost total absence of evidence on whether PFJ disorders are diagnosed and treated in general practice, despite the fact that knee pain problems are one of the most common reasons for people consulting their GPs (van der Waal et al., Reference van der Waal, Bot, Terwee, van der Windt, Schellevis, Bouter and Dekker2006; Royal College of General Practitioners’ Birmingham Research Unit, 2007). This study aimed to explore the extent to which GPs make PFJ-specific diagnoses, what these diagnoses are, and whether they are more commonly made in certain genders and age groups than in others.

Methods

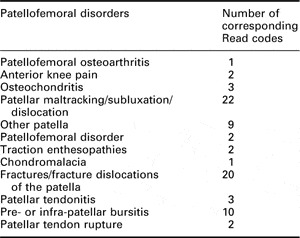

Annual age-stratified person consulting prevalence rates for patellofemoral disorders were calculated using 2006 data from the ‘Consultations in Primary Care Archive’ (CiPCA) – a fully audited computerised database of continuous morbidity recording used by the general practitioners (GPs) in eight general practices in North Staffordshire (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Clarke, Symmons, Fleming, Porcheret, Kadam and Croft2007) (ethical approval for CiPCA was granted by the North Staffordshire Research Ethics Committee [LREC Ref. No.03/04]). This was done in the following way. First, we identified all musculoskeletal knee-related Read codes, using the list generated by Jordan et al. (Reference Jordan, Kadam, Hayward, Porcheret, Young and Croft2010). Second, we excluded all non-diagnostic codes (ie, those that were used to indicate a clinical process, such as the ordering of X-rays or referral to secondary care). Third, we selected all those codes that related specifically to patellofemoral disorders and categorised these on the basis of presumed underlying pathophysiology (Table 1).

Table 1 Proposed categorisation of Read-coded consultations for patellofemoral disorders

Read codes/terms are available as an online appendix.

Fourth, we discounted repeated consultations by individuals given Read codes for the same patellofemoral disorders, in order to give an annual persons consulting prevalence rate. Fifth, we calculated the rate of consultation per 10 000 population for each diagnostic category. Finally, in order to determine whether some of these diagnostic Read codes are used more commonly for one gender than the other or in some age groups than in others, we stratified these consultation rates both by gender and by five 15-year age bands from the age of 15 years. To contextualise our results, we calculated prevalence estimates for consultations coded as knee osteoarthritis (OA; based on eight Read codes and excluding those specifically labelled as patellofemoral OA) for comparison, since OA is the most common joint disease (The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions) and a common cause of GP consultation (McCormick et al., Reference McCormick, Fleming and Charlton1995). In order to assist in interpretation of the results and due to the variable numbers of people consulting between categories, we calculated 95% CI (using the –ci- command with the binomial option in Stata 9.2).

Results

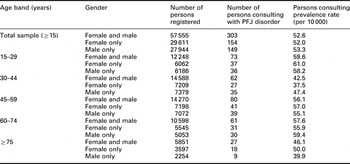

Of the 57 555 individuals aged ≥15 years registered with the eight general practices in 2006, 1782 made a knee-related consultation, of which 303 (17%) were coded as patellofemoral disorders, giving an annual persons consulting prevalence rate for PFJ disorders of 53 per 10 000 persons. Age- and gender-stratified person consultation rates for all PFJ disorders are given in Table 2. Generally, the prevalence rates (expressed as a proportion of persons registered with the GP practices in each age and gender stratum) did not differ greatly between the different strata. Two possible exceptions to this are worthy of note: in both the 30–44 and the ≥75 years age groups, there appear to be fewer person consultations. In the 30–44 years age group, this seems to be particularly the case among female consulters, whereas, in the ≥75 age group, it is the male consulters who seem to be especially infrequent.

Table 2 Number of persons registered with the general practices and persons’ consultation prevalence rates by age and gender strata

PFJ = Patellofemoral joint.

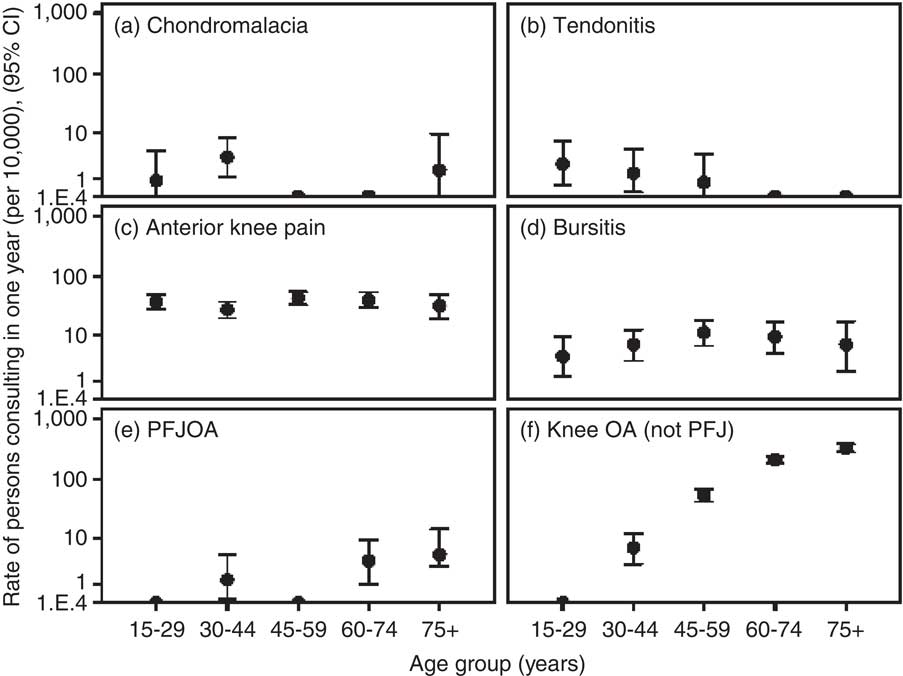

Categories with no individuals consulting in three out of the five age strata were discounted from further analyses. These were ‘osteochondritis’ (zero persons consulting in the study period), ‘maltracking/subluxation/dislocation’ (n = 7), ‘other patella’ (n = 1), ‘patellofemoral disorder’ (n = 1), ‘traction enthesopathies’ (n = 9), ‘fractures/ fracture dislocations’ (n = 5) and ‘patellar tendon rupture’ (n = 1). Age-stratified persons consulting prevalence rates (per 10 000 individuals) for the remaining patellofemoral disorders are given in Figure 1, together with the comparator, knee OA. In view of similar prevalence rates across the genders and the relatively small numbers within each age–sex stratum, we present the prevalence rates for males and females combined.

Figure 1 Annual persons consulting prevalence rates for patellofemoral disorders by age band, with knee osteoarthritis (not patellofemoral) for comparison (y axis is logarithmic scale)

‘AKP’ was by far the most common category of patellofemoral disorders recorded by GPs (persons consulting prevalence rate per 10 000 = 37.2), accounting for 12% of all knee-related consulters and 71% of all persons consulting and diagnosed with a patellofemoral disorder. Contrary to expectations, the consultation prevalence rate of AKP was relatively constant across the entire adult age range. ‘Bursitis’ was the next most common (persons consulting prevalence rate per 10 000 = 7.8), with prevalence rates again broadly similar across all ages. Cases of GP-diagnosed chondromalacia and patella tendonitis were rare and appeared mainly in adolescents and younger adults. In contrast to knee OA, there were few cases specifically diagnosed as PFJ OA (n = 13), with the majority occurring in adults aged ≥60 years.

Discussion

We estimate that one in six adults in the UK consulting general practice for a knee problem will be clinically suspected or diagnosed as having a patellofemoral disorder. Generally speaking, the overall persons consulting prevalence rate of patellofemoral disorders appears to be fairly consistent across the age and gender strata. The possible exceptions to this are the 30–44 years age group, where fewer women, in particular, were ascribed consultation codes for patellofemoral disorders, and the ≥75 years age group, where markedly fewer men were ascribed these consultation codes. Before jumping to hypothesise what might be the cause of these exceptions, it is worthwhile noting that the numbers involved here are so small, particularly in the case of the ≥75 years age group, that these variations may be random in nature.

Although the symptom code of ‘AKP’ is fairly commonly used by GPs across the age range of adolescents and adults consulting with knee problems, diagnoses of the specific patellofemoral disorders that may underlie such pain are not. While the term ‘AKP’ is clearly preferable in most circumstances to the historically oft-misused and misleading diagnosis of chondromalacia patellae (Fulkerson et al., Reference Fulkerson, Buuck, Dye, Farr and Post2004; Grelsamer, Reference Grelsamer2005; Pihlajamaki et al., Reference Pihlajamaki, Kuikka, Leppanen, Kiuru and Mattila2010), it has to be borne in mind that it may cover a whole raft of pathological causes (one authority lists 26 possibilities [Macnicol, Reference Macnicol1995]) that may require very different treatment approaches, both conservative and surgical.

As previously stated, there is a striking absence of evidence in the literature on the basic epidemiology of most patellofemoral disorders. AKP was found in this study to be the most commonly used ‘diagnostic’ code. One study from the United States attempted to quantify referrals for AKP from physicians to a primary care sports medicine clinic associated with a large managed care system (Butcher et al., Reference Butcher, Zukowski, Brannen, Fiesler, O'Connor, Farrish and Lillegard1996). The majority of these referrals were from family practice clinic providers, which included physicians, physician assistants and nurse practitioners. This study reported that out of 1857 patient contacts, 10.6% were for chronic AKP (Butcher et al., Reference Butcher, Zukowski, Brannen, Fiesler, O'Connor, Farrish and Lillegard1996). While these data can hint at the scale of the problem, they cannot give a true picture of consultation prevalence at the primary care level. Van Middelkoop et al. (Reference van Middelkoop, van, Berger, Koes and Bierma-Zeinstra2008) selected active sportspeople and non-athletes from their cohort of knee pain consulters in primary care, which was spread across 40 different GPs in the south-western Netherlands (van Middelkoop et al., Reference van Middelkoop, van, Berger, Koes and Bierma-Zeinstra2008). They found that 11.0% of these individuals were given a working diagnosis of ‘patellofemoral pain syndrome’ by their GP, compared with 12.0% given a Read Code for ‘AKP’ in the current analysis.

Published data regarding the prevalence of the other less-commonly used non-OA patellofemoral disorders in people with knee pain are similarly sparse. In their study of knee pain and radiographic OA in participants drawn from Veterans Affairs medical centres and the community, Hill et al. (Reference Hill, Gale, Chaisson, Skinner, Kazis, Gale and Felson2003) found that prepatellar and superficial infrapatellar bursitis were present in 12% of participants with knee pain and radiographic OA. One Chinese study of the comparative prevalence rates of chondromalacia among college students from a gymnastics department and students from a non-gymnastic department found the prevalence of chondromalacia patellae among the non-gymnasts to be 6% (although it should be made clear that their definition of chondromalacia patellae was akin to what is more commonly described as ‘AKP’ or ‘patellofemoral pain syndrome’, the diagnosis being arrived at on the basis of a clinical examination by a surgeon; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Kong, Cheng and Liang2003). The use of Read codes for these diagnoses was found to be uncommon in our review of consultation data: only 2.5% of per person knee-related consultations in 2006 were given one of the diagnostic codes pertaining to bursitis; the percentage for chondromalacia patellae was 0.4.

Patellofemoral OA, as a clinical entity, has attracted attention in recent years (Arendt, Reference Arendt2005; Donell and Glasgow, Reference Donell and Glasgow2007; Hinman and Crossley, Reference Hinman and Crossley2007; Kalichman et al., Reference Kalichman, Zhang, Niu, Goggins, Gale, Felson and Hunter2007; Becker et al., Reference Becker, Ropke, Krull, Musahl and Nebelung2008; Crossley et al., Reference Crossley, Marino, Macilquham, Schache and Hinman2009; Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Peat, Thomas, Wood, Hay and Croft2009; Neuman et al., Reference Neuman, Kostogiannis, Friden, Roos, Dahlberg and Englund2009). Cross-sectional community-based research studies suggest that structural changes consistent with OA may be more common in the PFJ than in the tibiofemoral joint (Lanyon et al., Reference Lanyon, O'Reilly, Jones and Doherty1998; Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Hay, Saklatvala and Croft2006; Szebenyi et al., Reference Szebenyi, Hollander, Dieppe, Quilty, Duddy, Clarke and Kirwan2006), and are likely to be an important source of symptoms in knee OA (Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, March and Sambrook2003; Englund and Lohmander, Reference Englund and Lohmander2005; Kornaat et al., Reference Kornaat, Bloem, Ceulemans, Riyazi, Rosendaal, Nelissen, Carter, Hellio Le Graverand and Kloppenburg2006; Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Peat, Thomas, Wood, Hay and Croft2009). Indeed, one of these showed that approximately a quarter of >50-year-olds who had experienced some knee pain in the past year had isolated patellofemoral OA in at least one of their knees (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Hay, Saklatvala and Croft2006). Therefore, it may seem strange that, while the annual incidence of new consultations for symptomatic knee OA has been estimated to be 0.5% (or 50 per 10, 000 individuals) of adults >55 years in the general population (Peat et al., Reference Peat, McCarney and Croft2001), the annual per person consultation rate for patellofemoral OA in the same age group should be as low as seven per 10 000, according to our review of general practice consultation data. This disparity may well be a reflection of the differential use of alternative diagnostic codes for a presenting problem by different GPs. Alternative codes often differ in the extent to which they are symptom-descriptive or patho-anatomic; hence, for instance, a diagnostic label of ‘knee pain’, ‘OA of the knee’ or ‘patellofemoral OA’ variously may be given for the older adult consulting with the same knee problem. Whether a GP uses one code or another is likely to vary from GP to GP (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Porcheret, Kadam and Croft2006) and may be both a reflection of the extent to which they are confident in or comfortable with the diagnosis and also, at least in part, a matter of habit (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Porcheret, Kadam and Croft2006).

This study used data from the CiPCA. GPs involved in this project undergo regular cycles of training, assessment and feedback in the quality of their computerised morbidity coding (Porcheret et al., Reference Porcheret, Hughes, Evans, Jordan, Whitehurst, Ogden and Croft2004; Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Porcheret and Croft2004; Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Clarke, Symmons, Fleming, Porcheret, Kadam and Croft2007). Over 90% of doctor contacts in these practices are given a morbidity code (Porcheret et al., Reference Porcheret, Hughes, Evans, Jordan, Whitehurst, Ogden and Croft2004). Such routine general practice consultation data constitute an important epidemiological resources that have the capacity to tell us much about consultation behaviour. However, it clearly has limitations when seeking information on the occurrence of specific patellofemoral disorders across the life course due to the fact that it captures only those complaints presented to, recognised and coded by the GP.

Use of only one year of consultation data resulted in small numbers of observations, which were insufficient for quantitative analysis. While expanding the period of consultation (eg, to five years) would enable more precise estimates to be made, and for the age-related pattern to be more clearly discerned, the overall conclusion – that the diagnosis of specific patellofemoral disorders is rare in general practice – would not be expected to change.

Our findings imply that ‘de novo’ population studies are needed to describe the occurrence of patellofemoral disorders in the general population. The implications for clinical practice are less clear. It appears that specific patellofemoral disorders are not being diagnosed in general practice. But does this matter? In an article about the taxonomical confusion of terminologies for patellofemoral conditions, Grelsamer (Reference Grelsamer2005) suggests that basket diagnoses, such as ‘AKP’, should be abandoned in favour of diagnoses that are more specific to the source of a patient's pain. To our mind, the answer to the question ‘Does this matter?’ depends on three factors: 1) The GPs’ capacity to diagnose specific patellofemoral disorders without the aid of sophisticated imaging techniques or arthroscopic examination. Authorities suggest that it is the clinical history taking and physical examination, rather than such techniques, that is central to the accurate diagnosis of patellofemoral disorders (LaBella, Reference LaBella2004; Brukner et al., Reference Brukner, Kahn, Crossley, Cook, Cowan and McConnell2007). 2) The extent to which these disorders need treating because they will not get better without intervention. Recent evidence, contrary to the traditional view of AKP problems being essentially benign and self-limiting (Sandow and Goodfellow, Reference Sandow and Goodfellow1985), suggests that symptoms may persist for many years into adulthood (Stathopulu and Baildam, Reference Stathopulu and Baildam2003) and may even pre-date the development of patellofemoral OA in later life (Utting et al., Reference Utting, Davies and Newman2005). 3) The existence of effective treatments specific to the particular patellofemoral diagnoses. Experts in the field are clear that there are many different treatments, conservative and otherwise, that are specific to the particular causes of patellofemoral pain (Juhn, Reference Juhn1999; Fulkerson et al., Reference Fulkerson, Buuck, Dye, Farr and Post2004; Post, Reference Post2005; Witvrouw et al., Reference Witvrouw, Werner, Mikkelsen, Van Tiggelen, Vanden Berghe and Cerulli2005; Fagan and Delahunt, Reference Fagan and Delahunt2008), although the true efficacy of many of these treatments has yet to be proven. The lack of certainty about these three factors leaves this question unanswered.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to produce population prevalence rates for various patellofemoral disorders across the life course. These data suggest that a significant proportion of adults with knee pain consulting in primary care in the UK are considered by their GPs to have disorders of the PFJ. Routine general practice morbidity recording has clear limitations in its ability to describe the epidemiology of patellofemoral disorders. Population-based studies are needed to fill this evidence gap.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Keele GP Research Partnership and the Informatics team at the Arthritis Research UK National Primary Care Centre. The ‘Consultations in Primary Care Archive’ (CiPCA) is funded by the North Staffordshire Primary Care Research Consortium and the National Coordinating Centre for Research Capacity Development (NCCRCD).