Introduction

In terms of morbidity and mortality, cancer remains one of UK’s biggest health problems. This has led to increased interest in how patients and professionals recognize cancer symptoms. This is particularly because European data show that one-year survival figures for many cancers are poorer in the United Kingdom than in comparable European countries (Verdecchia et al., Reference Verdecchia, Francisci, Brenner, Gatta, Micheli, Mangone and Kunkler2007; Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Forman, Bryant, Butler, Rachet, Maringe, Nur, Tracey, Coory, Hatcher, McGahan, Turner, Marrett, Gjerstorff, Johannesen, Adolfsson, Lambe, Lawrence, Meechan, Morris, Middleton, Steward and Richards2011). This suggests that people in the United Kingdom may be diagnosed at a later point in their cancer history than others in Europe, leading to the question as to why there should be this apparent delay in diagnosis. Although there may be a number of explanations for this, the prevalent view is that the pathway from first symptom to diagnosis might be partly responsible (Richards, Reference Richards2009). In the UK healthcare system, this pathway involves primary care, and most commonly general practitioners (GPs). Owing to their traditional gate-keeping role within the UK healthcare system, there is an emerging body of work on the role of GPs in the process to cancer diagnosis (Richards, Reference Richards2009; Hippisley‐Cox and Coupland, Reference Hippisley-Cox and Coupland2011; Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Shapley, Jordan and Jordan2011; Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Green, Martins, Elliott, Rubin and Macleod2013; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Rubin and Macleod2013).

There is agreement that cancer diagnosis in primary care is complex and attempts have been made to understand (Hamilton, 2009), and impact upon this process (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Shapley, Jordan and Jordan2011). Research has been carried out to comprehend in greater detail the symptoms that cancer patients present within primary care, and from these analyses to develop algorithms to assist GPs in assessing patients with potential cancer symptoms.

This resulted in desk-based risk assessment tools (RATs): decision-support tools for GPs that are intended to aid recognition of potential cancer symptoms. These tools have arisen from the Cancer Prediction in Exeter studies, and have been developed to quantify the risk of cancer in symptomatic primary-care patients (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Round, Sharp and Peters2005a, Reference Hamilton, Peters, Round and Sharp2005b; Hamilton, Reference Hamilton2009). The RATs were supplied in several formats including mousemats and flipcharts. The evaluation of these desk-based tools (for lung and colorectal cancer) showed that they appeared to help GPs in their selection of patients for cancer investigation by helping them confirm a need for investigation as well as allowing reassurance when investigation was not needed (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Green, Martins, Elliott, Rubin and Macleod2013; Green et al., Reference Green, Martins, Hamilton, Rubins, Elliott and Macleod2014). They were seen as particularly helpful in assisting GPs with cases of unusual presentations, and GPs also reported making different referral decisions as a result of using the RATs than those they might otherwise have made. Many GPs expressed a preference for electronic tools fully integrated into clinical systems to reflect the ways in which GPs work. We have reported these findings separately (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Green, Martins, Elliott, Rubin and Macleod2013; Green et al., Reference Green, Martins, Hamilton, Rubins, Elliott and Macleod2014). Subsequent to the desk-based study, Macmillan Cancer Support developed an electronic version – the electronic risk assessment tools (eRATs). This paper is a qualitative evaluation of the eRATs pilot.

Methods

The eRATs utilised software from the Informatica Clinical Audit Platform (iCAP), a software programme that some general practices use in addition to their clinical package. The iCAP is compatible with the various clinical packages used by practices (e.g., EMIS, VISION). The following three eRATs were piloted: the eRAT for lung cancer (non-smokers), the eRAT for lung cancer (smokers) and the eRAT for colorectal cancer. Each consists of three components as follows: (1) in-consultation on-screen prompts; (2) an interactive risk calculator and (3) audit tables of patients with calculated positive predictive values (PPVs).

In total, 53 practices were recruited to pilot these tools: 38 practices from Wales, six from Scotland and nine from England. All practices were invited by the research team to participate in an interview in order to evaluate users’ experiences of the three eRATs. The focus of the qualitative evaluation was on the applicability, usability and the process of implementation of the three eRATs in primary care. A total of 23 GPs accepted our invitation; more men (n=13) than women (n=10) GPs participated in the study. Purposive sampling was not possible because participants in the evaluation study were self-selecting. Nevertheless, participants in the interview served a diversity of practices located in deprived to affluent areas.

We determined that telephone interviews would be the most efficient way of data collection, based on the previous study we had conducted (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Green, Martins, Elliott, Rubin and Macleod2013; Green et al., Reference Green, Martins, Hamilton, Rubins, Elliott and Macleod2014). We agree with others that this interview method can be a preferred option to face-to-face interviews (Sturges and Hanrahan, Reference Sturges and Hanrahan2004; Novick, Reference Novick2008). The interviews were conducted between February and May 2012 by L.D. and T.G. The software had been installed for a minimum of six months before the interview.

A topic guide was specifically designed for the telephone interviews. We reiterate that the aim of this evaluation was to collect data on the (non)use of the tools and on the experiences of using the tool in everyday practice. The interview schedule focussed on the following topics:

-

∙ implementation and training;

-

∙ practical experience of using the eRATs;

-

∙ use of eRATs with patients in consultation;

-

∙ changes to practice influenced by the eRATs;

-

∙ positive and negative aspects of the electronic tools;

-

∙ influence on referral thresholds;

-

∙ use of the different components of each tool;

-

∙ general perception on the integration of eRATs in routine practice.

The analysis was guided by the following research question: Which factors facilitated or hindered the implementation and the use of these tools? During the analysis, regular meetings were held by the research team to discuss the emergent themes from the fieldwork material. To ensure a transparent and in-depth coding process, we applied a systematic approach to the analysis of the data. This included a first phase in which L.D. and T.G. performed a repeated close reading of each interview transcript in order to develop a detailed index of the key themes emerging from the data (Pope et al., Reference Pope, Ziebland and Mays2000). This led to a coding framework with descriptive code categories. This was followed by the second coding phase in which memoing and focussed coding led to translating the descriptive codes into analytical codes – that is, more abstract code categories (Hesse-Biber, Reference Hesse-Biber2007). This process led to our decision to map our findings to the normalisation process model (NPM), a theory-driven conceptual framework that assists in explaining the process by which interventions become routinely embedded in healthcare practice (May et al., Reference May, Finch, Mair, Ballini, Dowrick, Eccles, Gask, MacFarlane, Murray, Rapley, Rogers, Treweek, Wallace, Anderson, Burns and Heaven2007a, Reference May, Mair, Dowrick and Finch2007b). Following Wilkes and Rubin (Reference Wilkes and Rubin2009), who also retrospectively applied the NPM, we first provide a summary of the NPM as applied to this evaluation study before applying the results of our analysis to the four constructs in the model.

NPM as applied to the eRATs evaluation

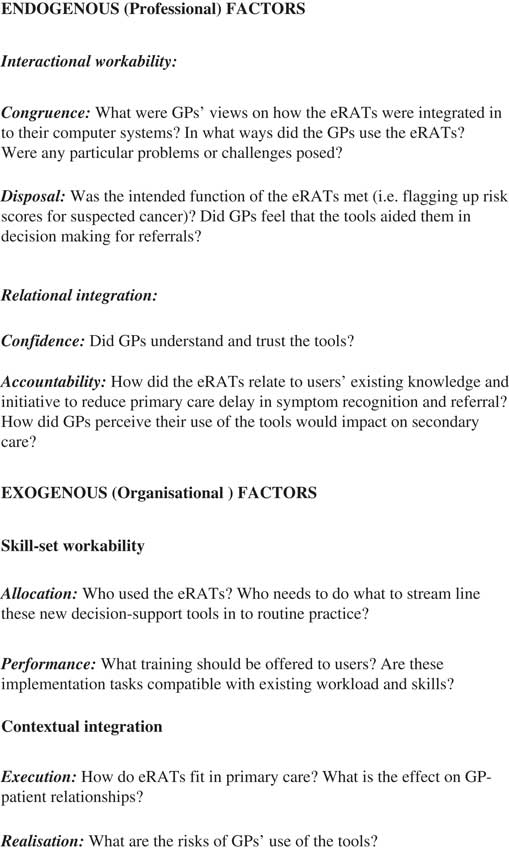

We conceptualized the implementation of the eRATs in primary care as ‘complex interventions’, because these are interventions built up from several components that can act independently as well as inter-dependently (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Fitzpatrick, Haines, Kinmonth, Sandercock, Spiegelhalter and Tyrer2000). The eRATs incorporated three components and introduced new tasks to the GPs who used them. These tasks not only included actions by the GP but also interactions between GPs and other practice staff. They consisted of multiple behavioural, technological and organisational elements. Qualitative evaluations of complex interventions are difficult because of the multi-faceted problems such an assessment poses (May, Reference May2006), but theory-driven conceptual frameworks can facilitate the data analysis. The NPM is such a framework (May et al., Reference May, Finch, Mair, Ballini, Dowrick, Eccles, Gask, MacFarlane, Murray, Rapley, Rogers, Treweek, Wallace, Anderson, Burns and Heaven2007a, Reference May, Mair, Dowrick and Finch2007b). It is recognized for its flexibility in application and can be used at different stages in a qualitative study (Wilkes and Rubin, Reference Wilkes and Rubin2009; MacFarlane and O’Reilly-de Brún, Reference MacFarlane and O’Reilly-de Brún2012). Moreover, the NPM is a robust conceptual model of implementation and integration processes around new health technologies and complex interventions (May, Reference May2006; May et al., Reference May, Finch, Mair, Ballini, Dowrick, Eccles, Gask, MacFarlane, Murray, Rapley, Rogers, Treweek, Wallace, Anderson, Burns and Heaven2007a, Reference May, Mair, Dowrick and Finch2007b). Its aim is to explain factors promoting or inhibiting smooth implementation of complex interventions and how these might become routinely embedded – that is, normalised – in healthcare practice. The four components, or ‘constructs’, of the NPM each reflect a quality of the complex intervention: (1) interactional workability; (2) relational integration; (3) skill-set workability; and (4) contextual integration. We have applied this to our evaluation of the eRATs (see Figure 1). In what follows, we demonstrate how our findings fitted into these four constructs.

Figure 1 The Normalisation Process Model as applied to this evaluation of electronic risk assessment tools

Interactional workability

Key themes: integration into GPs’ computer systems; facilitators and barriers in the use of the tools; and influence on referral behaviour.

We received a range of conflicting responses with respect to how well the eRATs fitted into current practice. For example, the tools sat within an electronic system separate from the clinical system, which necessitated additional log-on. This was reported as a barrier by some users. An additional factor in the GPs’ perception of the eRATs’ compatibility with their clinical systems was whether iCAP or Audit+ (which runs on top of the iCAP) was new to them, which was the case for approximately half of our respondents:

‘I think this issue of the computer resources is important. It’s got to be something that becomes a regular part of your practice, really. So from that point of view, certainly the IT people ought to sort that side of things out’.

(GP/10)

GPs used the three components of the eRATS to varying degrees, for example, how they reacted to the on-screen prompts was influenced by different factors: the approach of the doctor; the GP’s clinical experience; and time pressures in specific consultations. An important finding was, however, the danger of prompt overload. The vast majority of interviewees asserted that they experienced information overload, as pop-ups frequently flash on their computer screens. This could lead, as one GP commented, to ‘prompt fatigue’. It is, therefore, crucial that the threshold levels of all prompts are valid:

‘There are so many things on it, so many things popping up, so many things prompting you. You don’t probably respond to all the prompts, because there’s a box here, a box there, a box everywhere, and you don’t see everything (…) It’s such a busy screen you don’t respond to everything and this doesn’t pop up’.

(GP/3)

The second component, the interactive risk calculator, appeared to be used less frequently than the other two components, which might be related to the limited access to training in the use of the tools, resulting in a lack of awareness of all the tools’ functions. Some respondents indicated that they looked at the PPV tables, but only a minority actively reviewed these to consider patients who appeared to be at high risk.

The most significant function of the eRATs, flagged up by the vast majority of GPs, was that the tools raised their awareness of potential cancer symptoms and both reminded and alerted them to possible risks. Some GPs indicated that, although the eRATs might not have greatly influenced their referral rates, use of the tools meant that they reflected more often on symptom presentations or looked back at patients’ records:

‘Yes, I mean, I suppose a lot of us as GPs we do feel we’ve got a bit of a nose for a problem, you know, and what we want it … you know, I don’t send everybody with these symptoms up but I’m sending this one up because I’ve just got this gut feeling that this doesn’t feel right, you know. And you want that respect in a sense. And it might not fit in with your grid of symptoms [laughs]’.

(GP/23)

To summarise, GPs reported that the eRATs affected their referral thresholds to varying degrees, and, in turn, their decision-making; they were perceived as ‘back up’ tools that legitimised their referral decisions.

Relational integration

Key themes: GPs’ understanding of the eRATs; implications for referral rates;and compatibility with existing guidelines.

An important factor that emerged from our data was GPs’ desire to understand the research underpinning the eRATs:

‘You wouldn’t really use it without knowing what or how it was developed, why it was developed, and what it was for’.

(GP/20)

Some GPs referred to the original research to question its robustness, for example, they queried why the eRATs stored data for only one year, when the original research was based on patients’ records over two years. As aforementioned, participants felt that secondary-care practitioners should be made aware that eRATs were being used in primary care, and that they were informed the tools were evidence-based:

‘The biggest challenge [for a general roll-out of the eRATs] is of course the extra pressure, I think, on secondary care (…) I think you would have to liaise with secondary care, and maybe, there may well be implications for the workload, particularly for secondary care’.

(GP/15)

Although there were instances when GPs found the eRATs to be at odds with referral guidelines from their administrative and commissioning bodies or with existing local referral guidelines, overall, respondents felt that the tools complemented the National Institute for Clinical Excellence cancer referral guidance:

‘Other colleagues have said as well we’re far more aware of thrombocytosis and increased platelets. We weren’t aware that tended to increase the score for increased cancer risk’.

(GP/10)

‘Particularly for the lung cancer or the risk of lung cancer patients, I found it useful; I would say not so much for the bowel ones because it was based on the symptoms we’d already thought of as potentially risky’.

(GP/6)

Skill-set workability

Key themes: training how to use the new tools; eRATs in everyday practice; and factors effectingthe optimal use of the tools.

The vast majority of eRATs users were GPs. In only two cases did interviewees indicate that a practice nurse or manager had also used the tools, and in those instances they only used the third component of each tool (the PPV calculator, which brings up a list of all patients with a risk of either lung or colorectal cancer). Few of our respondents, however, used the calculated PPV tables in this proactive way, reasoning that it was not feasible for large practices to call patients in.

Our data suggest that user acceptability and usability of the tools would have been enhanced had the training been more comprehensive, accessible and appropriate. Different approaches were used to reach GPs with information and training: a WebEx (online video developed to support the training aspects of the pilot); an online discussion forum; and the possibility to discuss problems with a GP adviser on the telephone or via email:

‘It [the WebEx] was really long and drawn out is the honest answer; I think it was half an hour or an hour, I can’t remember. Yes, but actually there was a good eight minute slot that was brilliant that just explained it all, so I would be tempted I think from watching that thing it made a big, eh, it was really useful’.

(GP/6)

However, in many cases, respondents confirmed that only one GP or only the practice manager had watched the WebEx and then cascaded the information to other eRATs-users in the practice. This had consequences for the use and understanding of the tools.

In addition to accurate training, efficient use of the eRATs depends very much on the accuracy and the level of Read coding (i.e., a standard clinical terminology system). This, in turn, depends on the individual GP’s recording behaviour:

‘You have to have a consistent way of recording Read codes. As far as I know there is no agreement on how to record Read codes and the symptoms are not that much recorded, but then there is great variance in the people who record it’.

(GP/5)

Disparities in Read coding was evident throughout the data, as some respondents indicated that they coded everything, whereas others did not use Read coding very often. This variability in the use of Read codes by GPs is a limitation to the usefulness of any tool that relies on such coding.

Contextual integration

Key themes: outcomes of using the tools; impact on consultations; and medico-legal implications.

The most significant function of the eRATs, flagged up by the vast majority of GPs, is that the tools raised awareness about potential cancer symptoms and both reminded and alerted GPs to risks:

‘It’s just electronic highlight, makes you think even if you immediately dismiss it, at least that millisecond you’ve thought about it, and I think that is going to be useful at some point, but for how many people I don’t know’.

(GP/20)

Despite the danger of an overload of prompts, most of our participants perceived a future for electronic aids for GPs within the changing context of primary care. Most issues highlighted were germane to new interventions implemented into general practice, rather than to this particular intervention: multi-tasking expected from a GP within one consultation; constant time pressures; and the possibility of medico-legal repercussions:

‘There is, I suppose, the challenge of more and more prompts that, you know, say for us, your prompt box will get bigger and bigger. However, work in general practice is getting bigger and bigger, and more work’s going to come to general practice. So although it can cause irritation, the flip side of that is you can relax a little bit more and that you don’t have to remember absolutely everything (…) You know, how to sort the wheat from the chaff. So although people might think it’s irritating, it can be reassuring’.

(GP/22)

Interviewees stressed that the key aim of a consultation is to address patients’ ideas, concerns and expectations. However, during a consultation, on-screen prompts, usually related to QOF activities, often appear, which alert the GP to other tasks they need to complete; this in turn directs their attention away from the patient:

‘There’s a dichotomy between the very useful information that’s on the computer, and actually, you know, sort of, looking at the patients, and giving them, you know, proper attention, as they perceive it, you know’.

(GP/15)

Although not specifically asked about in the interviews, several respondents expressed concern with regard to the medico-legal implications of using eRATs, for example, of not referring a patient who had been brought to their attention via a prompt:

‘Quite a few partners were worried about any medico-legal implications with that. I think the one criticism was having the list of patient with PPVs. No one really liked that. That was worrying. We’re worried about if patients knew that you had a list of them with the risk and you hadn’t acted on it, what would be the implications? That was probably a point that put people off, really’.

(GP/17)

Several others commented on the contradictory pressures GPs experience, for example, being urged to limit referrals for financial reasons while simultaneously being asked to make earlier referrals of potential cancer patients. As our interviewees commented, however, all GPs would want to refer suspected cancer cases as early as possible.

Discussion and conclusion

Our analysis has demonstrated that developing and integrating new electronic tools into general practice is challenging. This finding is not new and should, therefore, not be surprising (May, Reference May2006; May et al., Reference May, Finch, Mair, Ballini, Dowrick, Eccles, Gask, MacFarlane, Murray, Rapley, Rogers, Treweek, Wallace, Anderson, Burns and Heaven2007a, Reference May, Mair, Dowrick and Finch2007b). However, this is the first time that an attempt has been made to incorporate eRATs for cancer diagnosis into GPs’ electronic systems. Useful lessons have emerged regarding cancer diagnosis, engaging with practices and the usefulness of the eRATs as diagnostic tools. First, GPs reported learning about new aspects of cancer symptom presentation as a result of using the eRATs, and thus the tools in themselves were educational. Second, there are clear challenges to the dissemination of training in using new electronic tools and implementing these into routine practice. Therefore, eRATs and other clinical decision-support tools need to be accompanied with training and guidance regarding their use. Although training tools can be distributed to practices, ensuring that practitioners access, use and understand them is challenging; thus, wider dissemination of the eRATs would necessitate adequate resources and follow-up support (Green et al., Reference Green, Martins, Hamilton, Rubins, Elliott and Macleod2014). Third, there was a lot of criticism about the glitches present in the eRATs at the time of our interviews; therefore, further development of these tools is required to make them fit for purpose.

The main limitation of this study is that it is probable that the GPs who took part in this evaluation were ‘keen’ and/or interested in cancer diagnosis, as the aforementioned GPs we interviewed were self-selecting. However, we did not end up exclusively with enthusiasts, which is reassuring in terms of trying to access and present a range of opinions.

This evaluation was preceded by an evaluation of the desk-based RATs (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Green, Martins, Elliott, Rubin and Macleod2013; Green et al., Reference Green, Martins, Hamilton, Rubins, Elliott and Macleod2014) and has reiterated several of the findings from that study, but has given new insights into the challenges and opportunities of transferring desk- or paper-based guidance to an electronic system – even at a time when electronic tools are the common currency of society. In their systematic review, Mansell et al. (Reference Mansell, Shapley, Jordan and Jordan2011) found limited evidence to suggest that complex interventions have addressed primary-care aspects of cancer recognition and referral to date, but concluded that those that offer improvements to practitioners’ knowledge of cancer symptoms might lead to changes in behaviour, which in turn impacts attitudes and decision‐making. Appropriately supported dissemination of clinical decision-support tools for cancer may well have a role in this endeavour.

In summary, the NPM facilitated our analysis as to how eRATs were adopted by some users while others were less enthusiastic. Many respondents confirmed that cancer was brought more to the forefront of their minds and that the eRATs, coined by users as ‘alerting mechanisms’ and ‘reminder tools’, were stimuli for discussion among GPs. Although we have identified albeit a limited workability, the eRATs have not been embedded, and thus not been ‘normalised’ as complex interventions into everyday practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Macmillan Cancer Support for funding this study and all GPs and GP advisers for participating. In particular, the authors thank James Austin, Albha Bowe and Tasia Malinowski from Macmillan Cancer Support for liaising with the research team and the practices. Thanks to Claire Ward for administrative support. Authors’ Contributions: U.M. designed the study and obtained the funding. T.G. and L.D. carried out the data collection and the data analysis. L.D. wrote the paper. T.G. and U.M. contributed to the editing of the paper. The authors acknowledge the valuable comments of the anonymous PHCRD reviewer.

Financial Support

The study was funded by Macmillan Cancer Support.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

This was a service development evaluation, and thus the NHS ethical approval was not required. We obtained ethics approval from the Hull York Medical School Medical School Ethics Committee.