Introduction

Depressive disorder arising in the early weeks following childbirth is common, affecting around 13% of women (O’Hara and Swain, Reference O’Hara and Swain1996). These disorders have the same clinical manifestation as depression arising at other times (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper and Murray1988; O’Hara, Reference O’Hara, Stuart, Gorman and Wenzel1997). Although most episodes spontaneously remit within four to six months, a significant minority persist beyond a year postpartum (Cooper and Murray, Reference Cooper, Campbell, Day, Kennerley and Bond1998). There has been considerable concern about the impact of postpartum depression on the mother–child relationship, and on child developmental progress. Child impairments across a wide range of developmental functions have been found (Murray, Halligan and Cooper, Reference Murray, Halligan and Cooper2010). Thus, the occurrence of depression in the postnatal period has been shown to pose a risk, principally in the context of wider socio-economic difficulties, for poor cognitive functioning in the child, especially boys (eg, Hay et al., Reference Hay, Pawlby, Waters and Sharp2001; Murray, Arteche, et al., Reference Murray, Arteche, Fearon, Halligan, Croudace and Cooper2010). Postnatal depression also poses a risk for behaviour problems in later childhood, especially where the postnatal episode becomes chronic (eg, Ghodsian et al., Reference Ghodsian, Zajicek and Wolkind1984; Sinclair and Murray, Reference Wickberg and Hwang1998; Morrell and Murray, Reference Murray2003). Finally, there is evidence for effects of postnatal depression on hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis functioning in offspring (Halligan et al., Reference Halligan, Herbert, Goodyer and Murray2004), which is itself a risk for depression; and, indeed, there is accumulating evidence for the effect of postnatal depression on the risk for depression in adolescent offspring, again, especially where the maternal postnatal depression becomes chronic (Hammen and Brennan, Reference Hammen and Brennan2003; Hay et al., Reference Holden, Sagovsky and Cox2008; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2011). Notably, the adverse impact of postnatal depression on these child outcomes has been found to be mediated by specific impairments in the mother–infant relationship (Murray, Halligan and Cooper, Reference Murray, Halligan and Cooper2010). This includes difficulties such as a lack of contingent, infant-focused responsiveness (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Marwick and Arteche1993), hostile and intrusive interactions (Morrell and Murray, 1993), withdrawn and disengaged behaviour (Murray, Halligan and Cooper, Reference Murray, Halligan and Cooper2010), and vocally communicated sad affect (Murray, Marwick and Artche, Reference Murray, Marwick and Arteche2010).

In light of these concerns about the impact of postnatal depression on child development, the question has been raised whether postpartum depression should be clinically targeted specifically to improve child developmental progress and mental health (McLennan and Offord, Reference Morrell, Slade, Warner, Paley, Dixon, Walters and Nicholl2002). There are arguments both in favour and against such a notion. In favour is the fact that screening for postpartum depression can be effected reliably and economically (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky1987; Murray and Carothers, Reference Murray, Arteche, Fearon, Halligan, Goodyer and Cooper1990; Morrell, Slade et al., Reference Morrell, Slade, Warner, Paley, Dixon, Walters and Nicholl2009), the relatively high prevalence of postpartum depression (O’Hara, Reference O’Hara, Stuart, Gorman and Wenzel1997), the reliability of the association between postpartum depression and adverse outcomes (Murray, Halligan and Cooper, Reference Murray, Halligan and Cooper2010), and the fact that several studies have demonstrated that therapeutic intervention is effective in alleviating maternal depression (eg, Holden et al., Reference McLennan and Offord1989; Wickberg and Hwang, Reference Wickberg and Hwang1996; Appleby et al., Reference Appleby, Warner, Whitton and Faragher1997; O’Hara et al., Reference Richman and Graham2000; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Murray, Wilson and Romaniuk2003; Morrell, Slade et al., Reference Morrell, Slade, Warner, Paley, Dixon, Walters and Nicholl2009). Against the idea of targeting maternal depression to improve child outcome is the fact that there is very little evidence that successful treatment of postpartum depression is of benefit to the mother–child relationship and the developing child (Nylen et al., Reference O’Hara2006; Foreman et al., Reference Forman, O'Hara, Stuart, Gorman, Larsen and Coy2007). Indeed, only three of the controlled trials on treatment have addressed these issues (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Fiori‐Cowley, Hooper and Cooper2003; Forman et al., Reference Forman, O'Hara, Stuart, Gorman, Larsen and Coy2007; Morrell, Warner et al., Reference Morrell, Warner, Slade, Dixon, Walters, Paley and Brugh2009). In the first UK study, although there was some benefit of treatment in terms of child behavioural disturbance and the mother–child relationship, this only emerged on measures that relied on maternal self-report (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Fiori‐Cowley, Hooper and Cooper2003). Similarly, in the US study, only parenting stress, and not the mother–child relationship or child outcome itself, showed a benefit (Forman et al., Reference Forman, O'Hara, Stuart, Gorman, Larsen and Coy2007). In the most recent study (Morrell, Warner et al., Reference Morrell, Warner, Slade, Dixon, Walters, Paley and Brugh2009), although some benefit of the intervention at 18 months postpartum was apparent in terms of infant behaviour problems, the effect was not strong, and, again, this relied entirely on maternal self-report. Before recommending targeting maternal depression in order to improve child outcome, it would be necessary to demonstrate more convincingly than has been the case to date that improvement in maternal mood is of material benefit to child developmental progress.

In the absence of such evidence, a further approach to this issue is to attempt to prevent the maternal depression itself. There have been several studies conducted with this specific objective. The results of 15 of these were summarised in a systematic review in 2005 (Dennis, Reference Dennis2005). At that time the conclusion drawn was that there was insufficient evidence to recommend the introduction of preventive interventions; however, the authors noted that interventions most likely to be beneficial were those that targeted high-risk women, and that were delivered individually and largely postnatally. Recently (Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2013), this review has been updated, now covering 28 trials reported between 1995 and 2011, involving almost 17 000 women. The conclusions drawn were considerably more positive than they had been in 2005.Thus, when considering depression at the last point of assessment, pooling all forms of intervention, a beneficial effect was reported on the prevention of depressive symptomatology (20 trials, n=14 727). A significant preventive effect was also found among the few studies that included a clinical diagnosis of depression (five trials; n=939). Further analyses revealed an immediate (13 trials; n=4907) and short-term (10 trials; n=3982) impact of the preventive interventions on depressive symptomatology. This preventive effect appeared to weaken at the intermediate postpartum time period between 17 to 24 weeks (nine trials; n=10 636), but was again significant when depressive symptomatology was assessed beyond 24 weeks postpartum (five trials; n=2936). Among trials that included a clinical diagnosis of depression, no preventive effect across an extended postpartum period was found, but there was a short-term beneficial effect (four trials; n=902). Data on the impact on child development are scarce, and on the quality of the mother–infant relationship, largely absent. Thus, from one trial that dichotomised maternal–infant attachment as secure or insecure, and two that examined mean scores on a maternal–infant measure (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Fraser, Dadds and Morris1999; Feinberg and Kan, Reference Feinberg and Kan2008), Dennis and Dowswell (Reference Dennis and Dowswell2013) conclude that there is no significant effect of the preventive intervention (two trials; n=268); and from the one trial that reported on infant cognitive development (Cupples et al., Reference Cupples, Stewart, Percy, Hepper, Murphy and Halliday2011) they also report no benefit (n=280).

Thus, while there is evidence for a positive benefit of preventive interventions on maternal mood, especially in the short term, it is notable that only one study to date (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Fraser, Dadds and Morris1999) has made a direct examination of whether a preventive intervention has any impact on the quality of the mother–child relationship, and few studies have considered the impact of intervention on any dimensions of child developmental outcome. This is clearly a question that requires research attention.

The preventive interventions examined to date have typically involved nurses or midwives providing general support (although there is also evidence for the benefit of more specific interventions, such as interpersonal psychotherapy). However, women who develop depression following delivery commonly report difficulties in their relationship with their infant and in managing infant behaviour problems (Murray, Reference Murray and Andrews1992; Seeley et al., Reference Sinclair and Murray1996). It might be expected that specific help in these domains would benefit vulnerable women in the early postpartum period. In view of these considerations, and consistent with the recommendations of Dennis and colleagues (2005; 2013), a trial was conducted of an individually delivered home-based preventive intervention provided by a health care professional, with the therapeutic input concentrated on the early weeks following delivery, and the intervention designed to provide the mother with specific help in managing the care of her infant, as well as general emotional support.

Method

The study was conducted in Reading, Berkshire. In one area, corresponding to the southern half of the city (Reading South), an efficacy, randomised controlled trial (RCT) was conducted; that is, appropriate women were identified (see Sampling section below) and assigned by simple randomisation, using consecutively numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes, to either routine primary care, or to an index preventive condition delivered by research health visitors (R-HV) (see Intervention and therapists section below).Footnote 1 In the northern sector (Reading North) there was no randomisation. Instead, all appropriate women were identified and treated by their local NHS health visitor (NHS-HV) who had been trained to deliver the intervention (see Intervention and therapists section below). Assessments were made at eight and 18 weeks postpartum, and at 12 and 18 months postpartum.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the local NHS Research Ethics Board and the University of Reading Research Ethics Board.

Sampling

Primiparous women attending the 20-week scan at the Royal Berkshire Hospital were screened for risk for postpartum depression using a predictive index (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Murray, Hooper and West1996). Women who scored highly on the questionnaire [ie, a score of more than 15 which represents a 30% risk of postnatal depression (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Murray, Hooper and West1996)], and met the study inclusion criteria (i.e., single pregnancy, stable residence in the area, English the home language) were identified as potential participants for the study. Sample size was calculated on the basis of a significant reduction in the prevalence of major depression at eight weeks, based on Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV diagnoses (SCID) criteria. All those agreeing to participate who were resident in Reading South were randomly assigned to either the Index (R-HV) or the control condition. Those women who were resident in Reading North were all allocated to the Index (NHS-HV) arm of the study. During the initial recruitment phase of the study, women were contacted either by telephone or letter to arrange a recruitment visit. All women assigned to the Index (R-HV) or the Index (NHS-HV) condition who gave their consent during recruitment were offered their assigned treatment. Those who completed treatment and the women from the control group were then assessed at eight and 18 weeks postpartum, and at 12 and 18 months postpartum.

Intervention and therapists

The intervention comprised three principal elements. First, supportive counselling was provided (as in Holden et al., Reference McLennan and Offord1989). The object was to encourage the women to express their feelings in a non-judgemental and supportive context. Second, specific strategies were employed to sensitise the mothers to their infants’ characteristics. In particular, selected items from the Brazelton Neonatal Behavioural Assessment Scale (NBAS) (Brazelton and Nugent, Reference Brazelton and Nugent1995) were used to form an Interactive Neonatal Assessment (manual available on request). These focused on infant responsiveness to the social and non-social environment (eg, visual tracking, responding to the mother’s voice), as well as individual differences in infant capacities for regulating their state and behavioural responses (eg, via habituation, and covering the infant’s eyes briefly with a soft cloth). Finally, specific help was provided to the mothers in managing infant behavioural problems [ie, sleeping, feeding, crying – as outlined in The Social Baby (Murray and Andrews, Reference Murray, Arteche, Fearon, Halligan, Croudace and Cooper2000)]. The therapists were all NHS employed health visitors who were provided with the intervention manual (available on request) and training in its use. For the Index (R-HV) arm, two health visitors were seconded to work within the research team, and were provided with training over a three-month period. Specifically, they received formal training in the administration of the NBAS (Brazelton and Nugent, Reference Brazelton and Nugent1995); and they delivered pilot interventions to a sample of high-risk mothers, under the supervision of P.J.C. and L.M. For the Index (NHS-HV arm), training was provided to all the NHS employed health visitors working in the Reading North sector during five days of instruction over a month, with ongoing supervision. The intervention involved 11 home visits: two antenatally and then nine in the first 16 weeks postnatally.

Assessments

Post-intervention assessments were made, blind to treatment condition (including whether the woman was from Reading South or Reading North) at eight and 18 weeks postpartum, and at 12 and 18 months postpartum. The first two of these were conducted in the women’s own homes, and the latter two in the research base. At all four time points assessment was made of maternal mood using the SCID (First et al., Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1996), and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky1987). At the eight and 18 week postpartum assessment, a video recording was made of the mother and her infant engaged in a face to face interaction (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Halligan and Cooper1996). In addition, at the first three assessments mothers completed a self-report questionnaire on relationship problems with the infant, and infant behaviour problems (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Fiori‐Cowley, Hooper and Cooper2003); and at the 18-month postpartum assessment, mothers completed the behaviour screening questionnaire (BSQ) (Richman and Graham, Reference Seeley, Murray and Cooper1971), modified for this age group (Murray, Reference Murray and Andrews1992), to assess child behaviour problems. At 18 months, assessment was made of infant mental development, using the Mental Development Index (MDI) of the Bayley II Scales (Bayley, Reference Bayley1993), and the Ainsworth Strange Situation Procedure was used to assess infant security of attachment (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978). Both are ‘gold standard’, reliable, measures that are widely used in infancy research and have been shown to be sensitive to effects of maternal postnatal depression (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Halligan and Cooper1996). In the case of the Bayley scales, there have been reports that infant gender moderates this relationship, with boys being more adversely affected, whereas girls appear to have good cognitive outcome (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Cooper, Wilson and Romaniuk2010). In the current study, therefore, we examined the moderating effect of child gender on the relationship between intervention and performance on the Bayley II MDI. All assessments and coding of videos were conducted by trained independent assessors/coders who were masked with respect to treatment condition. Finally, a set of questions was drawn up to ascertain participants’ perceptions of the health visitor support they received. To enable comparison with reports concerning the trained study health visitors (Reading South and North) and the NHS-HV providing routine care for the control group, these questions were formulated as assessments of the extent, and way in which the women found the health visiting input helpful, with scores ranging between 0 (not at all) and 3 (completely). This questionnaire was completed at 18 weeks postpartum.

Data analysis

Summary statistics were calculated for the demographic characteristics, predictive index components, and outcome measures by treatment group. A multilevel modelling framework was used to estimate the effect of the Index (R-HV) condition compared with the control group for outcomes measured over time. Linear models were used for continuous measures – that is EPDS, maternal sensitivity, and infant engagement. Logistic regression was used for binary outcome measures – that is SCID diagnoses of depression, and the presence of marked to moderate behavioural and relationship problems. For each measure, a first set of models assessed the effect of treatment, and its interaction with time of assessment, while a second set of models assessed the effect of treatment, and its interaction with the level of risk (as defined by scores being either higher or lower than the median of the predictive index score). For the outcomes measured only at 18 months, linear regression was used to analyse the BSQ scores and the Bayley Mental Development scores, while logistic regression was used to model infant attachment. These models initially assessed the effect of treatment, and subsequently also included its interaction with the predictive index score. Only for the Bayley Mental Development score, a final model assessed the interaction between treatment and child gender. To compare the Index (NHS-HV) and control conditions, the same set of analyses was conducted. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 22, for Microsoft Windows. A P-value <0.05 was considered significant, with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Results

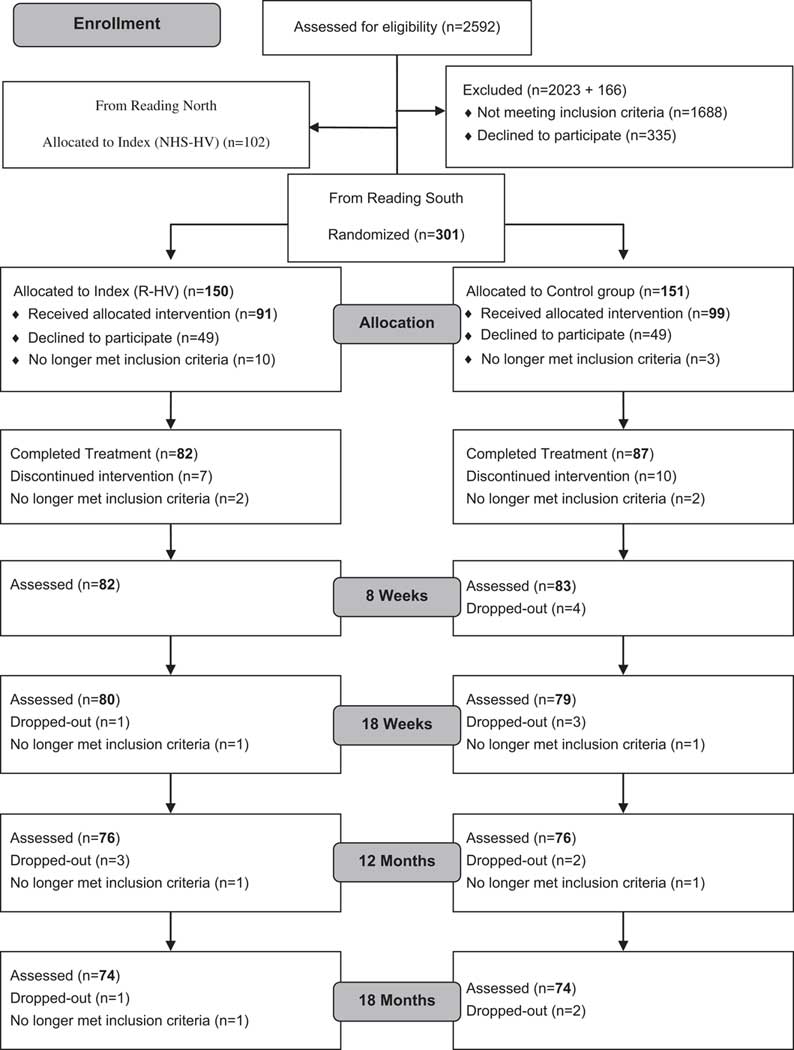

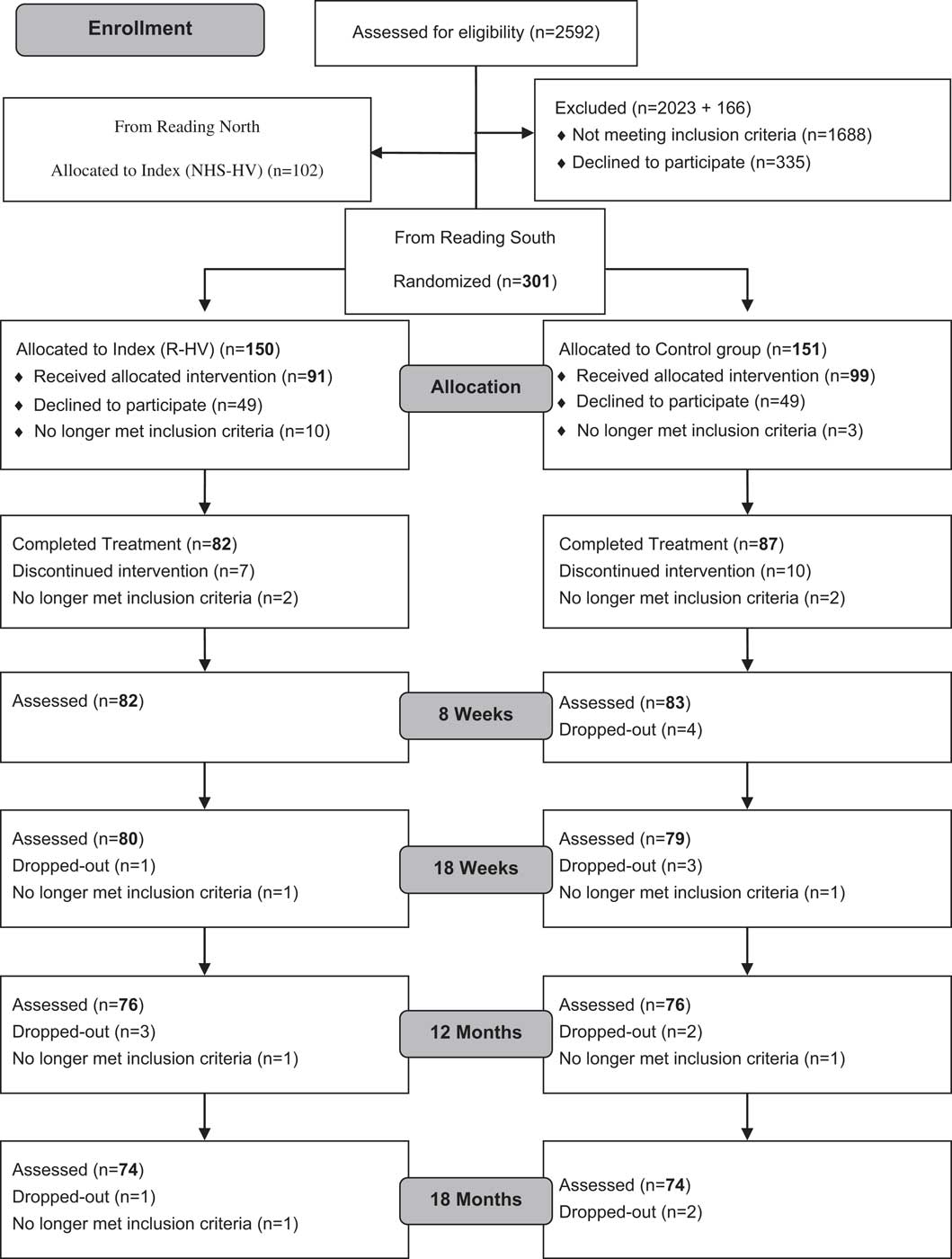

As can be seen from Figure 1, 87% of the 2592 women selected for screening completed the questionnaire. Six hundred and forty-five women (29% of the women who completed the questionnaire) scored above the cut off on the predictive index. One hundred and sixty-six of these women were assigned to a separate ongoing study of parenthood before trial randomisation, and they are not considered further. Of the remaining women, 76 were ineligible to participate (eg, twin pregnancy, moving away from area), leaving 403 who were identified as potential recruits for the study. One hundred and thirteen of the 150 randomly assigned to the Index (R-HV) (75%) agreed to a recruitment visit, as did 78 of the 102 assigned to the Index (NHS-HV) (76%), and 107 of the 151 assigned to the control group (71%). During the recruitment visit, 61% of the women randomly allocated to the Index (R-HV) condition consented to participate in the study, as did 75% of the Index (NHS-RV) and 66% of the controls. Of the women who consented to participate in the study, 90% of the Index (R-HV) women and 79% of the Index (NHS-HV) women completed treatment; and 88% of the controls were retained in the study over the equivalent period of time. At the eight week postpartum assessment, all the women who completed treatment in the Index (R-HV) conditions were assessed, as were all but two of the women in the Index (NHS-HV) group and all but four of the controls. At the 18 month assessment, 90% of the Index (R-HV) women who had completed treatment were assessed, as were 85% of the Index (NHS-HV) and 85% of the controls.

Figure 1 Sampling and CONSORT Diagram for Reading South

Table 1 provides details of the three groups, in terms of the mother’s age, child’s gender, and their responses to the individual items of the predictive index. It is apparent that there were no material differences between the Reading South index and control groups at baseline. The analyses below are presented in terms of overall comparative statistics. (Details of exact scores and distribution on all measures are available on request).

Table 1 Maternal age, child gender, and predictive index items, according to group at baseline

a Means, standard deviations, and percentages are calculated for valid cases [range: Index (R-HV)=81–82; Index (R-HV)=57–58].

b Of the women who were depressed at other times in their life.

c Of the women who currently have a partner.

d Of the women who currently have a mother.

e Apart from mother or partner.

R-HV=research health visitors; NHS-HV=National Health Service health visitors; GCSE=General Certificate of Secondary Education.

Maternal mood

EPDS

The distribution of scores on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale was positively skewed, and the variable was square-root transformed before analysis to achieve normality. From Table 2, it can be seen that at each assessment the mean EPDS scores were similar for each of the three groups. No main effect of group (all Ps>0.857), or interaction with time (all Ps>0.235) was found for either the Index (R-HV) versus control, or the Index (NHS-HV) versus control comparisons. EPDS scores were, however, significantly predicted by the total risk index score [F(1, 228.14)=10.75; P=0.001]. For the Index(R-HV) versus control comparison, risk did not moderate the relationship between intervention and EPDS (P=0.511), whereas there was such moderation for the Index(NHS-HV) versus control comparison: those in the index condition with relatively low risk had lower EPDS scores (P=0.03).

Table 2 EPDS scores and depression percentages, according to group and child age

a Range: 0–24; the higher the score, the higher the depressive symptomatology.

EPDS=Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; R-HV=research health visitors; NHS-HV=National Health Service health visitors; SCID=Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV diagnoses.

SCID

The proportion of women who were depressed at each assessment is shown in Table 2 for each of the three groups. Compared with the control condition, for both Index (R-HV) and Index (NHS-HV), at none of the assessments was there a main effect of group (all Ps>0.687), nor was there an interaction with time (all Ps>0.597). The total risk index score predicted the overall likelihood of being depressed [F(1, 836)=17.22; P<0.001]; however, for both Index (R-HV) and Index (NHS-HV), the risk score did not moderate the relationship between intervention and SCID status (all Ps>0.444).

Mother–infant interactions

Maternal sensitivity

As can be seen from Table 3, in terms of the levels of maternal sensitivity, compared with the control condition, for both Index (R-HV) and Index (NHS-HV), there was no main effect of group at either 8 or 18 weeks (all Ps>0.365), nor was there an interaction with time (all Ps>0.759). Maternal sensitivity was not predicted by the total risk index score (P=0.638); and for both Index (R-HV) and Index (NHS-HV), the risk score did not moderate the relationship between intervention and maternal sensitivity (all Ps>0.535).

Table 3 Maternal sensitivity and infant engagement according to group and child age

a Range: 1.40–5.00; the higher the score, the higher the level of maternal sensitivity.

b Range: 1.00–5.00; the higher the score, the higher the level of infant engagement.

R-HV=research health visitors; NHS-HV=National Health Service health visitors.

Infant interaction

As can be seen from Table 3 which concerns levels of infant engagement, compared with the control condition, there was no effect of group for either Index (R-HV) or Index (NHS-HV) at either 8 or 18 weeks (all Ps>0.233), and nor was there an interaction with time (all Ps>0.231). No relationship was found between infant engagement and the total risk index score (P=0.123); and for neither Index (R-HV) nor Index (NHS-HV), did the risk score moderate the relationship between intervention and infant engagement (all Ps>0.563).

Reported behaviour and relationship problems

For reported behavioural problems at 8 and 18 weeks, and at 12 months, as shown in Table 4, comparing the women in the Index (R-HV) and the control condition, there was no main effect of group at any time point (all Ps>0.570), nor an interaction with time (all Ps>0.229). For the comparison between the Index (NHS-HV) group and the control group, there was a main effect of group (F(1, 382)=9.440; P=0.002), with women in the former being less likely to report behaviour problems, regardless of time. No interaction between time and group was found (P=0.882). The total risk index score did not predict reported behavioural problems; and for neither Index (R-HV) nor Index (NHS-HV) did the risk score moderate the relationship between intervention and the presence of behaviour problems (all Ps>0.110).

Table 4 Behaviour and relationship problems, and BSQ scores, according to group and child age

a Range: 0.00–14.00; the higher the score, the greater the presence of behavioural problems.

BSQ=behaviour screening questionnaire; R-HV=research health visitors; NHS-HV=National Health Service health visitors.

In relation to reported relationship problems, also measured at 8 and 18 weeks and 12 months, as shown in Table 4, there was no main effect of group for the comparison between the control and the Index (R-HV) conditions (P=0.131), or between the control and the Index (NHS-HV) conditions (F(1, 360)=3.404; P=0.066). Neither comparison showed an interaction between group and time (all Ps>0.722). The total risk index score did not predict reported relationship problems in the sample as a whole (P=0.202), and, for the comparison between Index (NHS-HV) and controls, no moderating effect of risk score on the relationship between intervention and relationship problems was found (P=0.985). In the comparison between Index (R-HV) and controls, however, the risk score was found to moderate the relationship between intervention and reported relationship problems (P=0.002): those in the index group with relatively lower risk were less likely to report relationship problems.

The distribution of scores on the BSQ, collected at 18 months, was positively skewed. The variable was therefore square-root transformed. The BSQ scores, shown in Table 4, did not differ significantly between either of the index conditions and the control condition (all Ps>0.692). No relationship was found between BSQ scores and the total risk index score (P=0.065); for the Index (R-HV) versus control comparison there was no moderation of risk (P=0.131), however there was for the Index(NHS-HV) versus control comparison (P=0.051): those in the index group with relatively lower risk had lower BSQ sores.

Bayley Scales of MDI

For the Bayley MDI score, at 18 months, neither the Index (R-HV) versus control nor Index (NHS-HV) versus control comparisons showed a main effect of group (both Ps>0.765). Total risk index scores were negatively associated with Bayley MDI scores (P=0.023), with higher risk index scores being associated with lower Bayley MDI scores. For neither Index (NHS-HV) nor Index (R-HV), did the risk score moderate the relationship between intervention and Bayley MDI score (all Ps>0.267). When gender was considered as a possible moderator of the relationship between intervention and Bayley MDI score, one significant finding emerged (P=0.020): the girls in the Index (R-HV) group had a 13.85 MDI advantage over the boys from the same group (P<0.001 Bonferroni corrected), and an 8.20 IQ advantage over the girls from the control group (P=0.056 Bonferroni corrected). For the Index (NHS-HV) groups, the girls had an IQ advantage over the boys of 7.04 points, although this does not represent significant moderation (P=0.178 Bonferroni corrected). Among controls, gender was unrelated to Bayley MDI score (M’s=94.52 and 95.46 for boys and girls, respectively; P=0.829 Bonferroni corrected).

Infant attachment security

At 18 months, no difference was found in the proportion of securely attached infants of control group mothers (66.67%) compared with infants of Index (R-HV) mothers (65.71%) and infants of Index (NHS-HV) mothers (50.98%) [χ 2(1)=0.01 and χ 2(1)=3.06, respectively; Ps>0.080]. The total risk index score did not predict infant attachment (P=0.809); and for neither Index (NHS-HV nor Index (R-HV), did the risk score moderate the relationship between intervention and infant attachment (both Ps>0.510).

Perceptions of health visitor support

Table 5 shows items and mean scores for the questionnaire concerning perceptions of health visitor support. It is apparent those in the two index intervention groups felt better supported than the controls, both emotionally and practically (all Ps<0.004); and they also felt their relationship with their infant to have been been better facilitated (all Ps<0.001).

Table 5 Perceptions of the intervention questionnaire scores according to group

a Range for all questions: 0.00–3.00; the higher the score, the higher the perception of support.

R-HV=research health visitors; NHS-HV=National Health Service health visitors.

Discussion

A recent systematic review of the controlled trials examining the impact of preventive interventions for postnatal depression reported a positive benefit (Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2013). This effect has mainly been shown on depressive symptoms in the early weeks following delivery. No impact on the quality of the mother–infant relationship or child development has been shown, but only a handful of studies have included child variables as outcomes. This is a significant gap in the literature. There is considerable evidence of both a strong association between postpartum depression and impairments in the mother–child relationship (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Halligan and Cooper1996), and between such impairments and adverse child outcomes (Murray et al., Reference Nylen, Moran, Franklin and O'Hara2010). The current trial attempted to address this gap by delivering a preventive intervention that, in the context of providing general emotional and practical support, directly addressed the mother–infant relationship. This intervention was delivered by trained health visitors to women at established raised risk for postpartum depression. Maternal mood was assessed and direct assessment was made of both the quality of the mother–infant relationship and critical dimensions of child development progress. Assessment of efficacy was made in a standard RCT; and an attempt to assess effectiveness was made by including a trial arm where the therapists were NHS-HV.

The strengths of the trial were the rigorous manner in which the high-risk samples were identified, the systematic assessment of maternal mood, the mother–child relationship and child outcome, and the provision of a specifically targeted intervention. Although there were no strong empirical grounds for believing that a mother–child intervention of the sort delivered would be of benefit to maternal mood, it was reasonable to expect benefit for child outcome.

No impact of the intervention was found on maternal depression, either in terms of level of symptoms or a diagnosis of depressive disorder at any of the assessment points. (Although women at relatively lower risk in Reading North showed some benefit of the intervention in terms of their EPDS scores, since this effect did not emerge from the formal RCT, its significance must be regarded with great caution). This absence of therapeutic benefit was not a function of unexpected low levels of depression in the control sample. Indeed, the period prevalence of depressive disorder at eight weeks postpartum for the intervention and the control groups was very much in line with the rate the predictive index would have predicted, in the absence of an intervention (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Murray, Hooper and West1996). The unavoidable conclusion must be that, in terms of depressive mood and disorder, this intervention was not of benefit to the women. This was a surprising finding because a core component of the intervention was supportive counselling, a therapeutic approach that has, in some previous studies (though not others), been found to have a preventive effect (Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2013).

A notable feature of the current study was the fact that direct assessment of the quality of the mother–infant relationship was made. No benefit of the intervention for the mother–child relationship was found. Thus, no treatment effect was apparent for the level of maternal sensitivity in interaction with the infant, or the levels of infant engagement. These null findings were largely replicated in the maternal self-report measures of infant behaviour and relationship problems. Again, this was an unexpected finding. Interventions of the sort being delivered, which focus on the mother–child relationship and infant problems have, in other contexts, been shown to be of benefit (eg, Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Tomlinson, Swartz, Landman, Molteno, Stein and Murray2009). It is of interest that these negative findings, based on both objective measures of the mother–child relationship and maternal self-reports of problems, are in contrast to the views participants themselves expressed about the utility of the intervention: the mothers reported the intervention to be of considerable emotional and practical support, and to be of significant help in enhancing their appreciation of their infant’s abilities and their ability to communicate with their infants.

This casts in doubt the validity of using maternal reports of the benefit of mother–infant interventions in intervention studies.

Scant attention has been paid in previous preventive studies of the impact of treatment on child outcomes, such as attachment and cognition. Both of these outcomes were carefully assessed in the current trial using rigorous methods of assessment. No impact of the intervention was found for either security of infant attachment or cognitive development. These are unsurprising findings, given the lack of effect on both maternal depression and the quality of the mother–child relationship.

It does not seem likely that the reason for our null findings is that the predictive index we used to identify participants failed to function as intended. First, the proportion of women in the control condition who experienced depression in the weeks following childbirth was in line with expectations. Second, overall antenatal risk was found to be a reliable predictor of certain key outcomes, namely maternal depressive mood and disorder, and the 18 month infant Bayley MDI score. While there was some suggestion that the intervention was of some benefit to those at relatively lower antenatal risk, effects were neither consistent not strong. One unexpected moderation effect did emerge: in terms of child Bayley MDI score, there appeared to be a reliable benefit of the intervention for girl children. In light of the plethora of other negative findings, this effect must be regarded with considerable caution.

The thrust of the recent systematic review of preventive interventions for postnatal depression (Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2013) is that some forms of intervention do appear to be of benefit to maternal mood, especially in the short term. This is an important advance as, until recently, the research appeared to be pointing to the absence of a preventive effect (Dennis, Reference Dennis2005). Thus, positive evidence has emerged for intensive, individualised postpartum home visits provided by public health nurses or midwives, lay (peer)-based telephone support, and interpersonal psychotherapy (Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2013). Whether these forms of intervention are also of positive benefit to the mother–child relationship and child developmental progress remains to be demonstrated. What the findings of the current study suggest is that a preventive intervention, delivered by health visitors to a high-risk UK sample, which focuses on the mother–infant relationship, is likely to be ineffective, both at preventing the maternal mood disorder and the associated mother–infant relationship disturbances.

It is of some interest to note that in a context very different from the United Kingdom one in which this trial was conducted, the delivery of the current intervention produced very different findings (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Tomlinson, Swartz, Landman, Molteno, Stein and Murray2009). Thus, when the intervention (with some culturally appropriate modifications) was delivered to a group of impoverished South African mothers, while only a modest positive benefit on maternal mood was found, the intervention was of significant benefit to both the quality of the mother–child relationship and infant security of attachment. Why there should be such a contrast between these two contexts is moot. Two possible explanatory candidates are worth considering. First, in the UK study the intervention visits stopped at two months postpartum, whereas in the South African study they continued until six months. The extra support provided could have been a key difference. A second possible explanation concerns sample engagement with the content of the intervention. The South African women were extremely keen to engage in the intervention because they believed that it would be benefit to their children. Motivating the UK sample was much more problematic.

Given that the findings of the current study are somewhat out of step with the conclusions drawn from other recent preventive intervention studies, we are wary of making strong recommendations on the direction for future research. However, it is clear that even where preventive effects have been found, they are modest compared with the impressive results obtained from treating identified depression. In light of this, clinical practice may well benefit more from refinement of identification and treatment procedures than further elaborating preventive ones. Further, for both preventive and treatment studies, a reliable impact on the mother–child relationship and child outcome remains to be demonstrated. This must represent a major focus for future research.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Shirley Goldin and Angela Cameron for assistance in supervision of health visitor practice, Joanna Hawthorne for training the health visitors in the administration of the NBAS, the health visitors who acted as therapists, and the mothers who participated in the study. They also thank Liz McGregor for assistance with recruitment, and Liz Schofield and Claire Lawson for help with conducting assessments and coding. Finally, they thank Liz Andrews and the late Julia Pemberton for delivering the intervention in Reading South and assisting in the training of the Reading North health visitors.

Financial Support

The study was funded by the National R and D programme MCH-1–44.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.