Introduction

The administration of epinephrine has been a cornerstone of cardiac arrest resuscitation for decades.Reference Paradis and Koscove1 Stimulation of alpha receptors increases myocardial and cerebral blood flow and leads to increased rates of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), while beta stimulation increases myocardial oxygen demand and arrhythmogenicity.Reference Yakaitis, Otto and Blitt2,Reference Ditchey and Lindenfeld3 Since 1974, the American Heart Association (AHA; Dallas, Texas USA) has published Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) guidelines on cardiac arrest. While a variety of adrenergic and antiarrhythmic medications have come and gone, epinephrine remains the only drug that continues to be recommended for all nontraumatic cardiac arrests.

Evidence for the use of epinephrine in cardiac arrest continues to evolve, and while recent studies continue to affirm increased rates of ROSC associated with epinephrine use, there is variability in the most critical outcome: neurologically intact survival.Reference Lin, Callaway and Shah4–Reference Perkins, Ji and Deakin7 The 2018 PARAMEDIC-2 trial is the largest trial of epinephrine in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and demonstrated an increase in the primary outcome of survival at 30 days (3.2% versus 2.4%) but no statistically significant difference in survival to hospital discharge with a favorable neurologic status.

Treating a patient in cardiac arrest is a fundamental role of Emergency Medical Services (EMS). It is essential for EMS systems to ensure that treatment protocols and resuscitation practices are informed by scientific evidence and include new advances in the understanding of resuscitative medicine. This project sought to describe the current state of administration of epinephrine within prehospital cardiac arrest protocols across the United States.

Methods

An internet search engine was used during the period of July 1, 2021 through December 31, 2021 to access publicly available state EMS agency websites in all 50 US States and Washington, DC. The EMS treatment protocols in place as of January 1, 2018 were compared to the protocols in place as of January 1, 2021. Any changes in epinephrine administration in cardiac arrest management protocols were recorded including dosage, frequency, and difference between shockable or non-shockable rhythm. For any states in which the 2021 protocol was not found online, the state medical director’s office was contacted for further information. Information for states unobtainable despite these efforts, as well as those states that do not have state-wide protocols, were excluded. Summary and descriptive statistics were performed in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp.; Redmond, Washington USA). Two reviewers, KM and BJ, verified the protocols independently. If there was an inconsistency, a tie-breaking decision was made by EG. This project was reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine (Baltimore, Maryland USA) Institutional Review Board, protocol number 00298128.

Results

Of the 50 states and the District of Columbia, 21 (41.2%) yielded complete data from both 2018 and 2021. In 11 states (21.6%), the 2018 protocols were unable to be accessed. However, all 11 states had 2021 protocols consistent with current ACLS guidelines and thus it was assumed that there was no change from 2018. A further 19 (37.3%) states were confirmed to have no state-wide protocols. Table 1 lists which states utilized state-wide protocols and the data availability.

Table 1. Protocol Data Availability for Each State and the District of Columbia

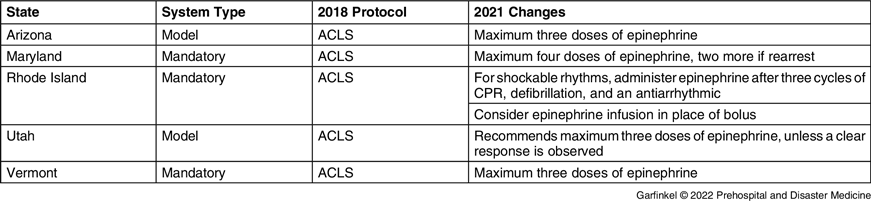

Of the 32 (62.7%) states with state-wide protocols, five (15.6%) recorded a change between 2018 and 2021 in epinephrine administration during cardiac arrest and 27 (84.4%) had no change. The five states with recorded changes were Arizona, Maryland, Rhode Island, Utah, and Vermont (Figure 1). The differences are listed in Table 2. Arizona and Utah have model protocols to guide local protocols, while Maryland, Rhode Island, and Vermont have mandatory state-wide EMS protocols.

Figure 1. Map of States with State-Wide Protocols which had Changes in Protocol during the Study Period.

Abbreviation: EMS, Emergency Medical Services.

Table 2. States with Changes in Epinephrine Use in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest from 2018 through 2021

Note: ACLS protocol is consistent with the American Heart Association’s Advanced Cardiac Life Support algorithm.

Abbreviations: ACLS, Advanced Cardiac Life Support; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Arizona limits epinephrine to a maximum of three total doses. Maryland limits epinephrine to a maximum of four doses of epinephrine, plus an additional two doses if the patient rearrests following ROSC. Utah recommends considering limiting epinephrine to three doses unless there is a response. Vermont limits epinephrine to three doses.

Rhode Island changed the protocol from administering epinephrine every three-to-five minutes in all rhythms to administering epinephrine after three cycles of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), electrical, therapy, and one dose of antiarrhythmic in shockable rhythms. In addition, Rhode Island is the only state which added an epinephrine infusion as an option in place of frequent boluses.

In all state protocols in force at January 1, 2018, except for New Jersey, epinephrine dosing and frequency was consistent with the ACLS guidelines. New Jersey limited epinephrine to a maximum of three doses. No states added or eliminated epinephrine from their protocol during the studied period.

Discussion

This study showed that only a limited number of states changed protocols to reflect the recent literature regarding epinephrine in cardiac arrest. Amongst these states, there appears to be an emerging trend towards limiting epinephrine dosage. The most frequent dose limitation was to a total of three milligrams, except for Maryland which limits the dosage to four milligrams. No study has conclusively looked at the ideal amount of epinephrine to be administered during cardiac arrest and international guidelines do not recommend a maximum epinephrine dose.Reference Merchant, Topjian and Panchal8 Fothergill, et al demonstrated a significant drop in the adjusted odds ratio for survival to hospital discharge once the third dose of epinephrine was administered, from 0.7 for two doses of epinephrine to 0.15 for three or greater doses.Reference Fothergill, Emmerson and Iyer9 Higher epinephrine dosing is associated with a longer resuscitation period, which is clearly associated with a worse outcome, thus identifying the optimal dosing of epinephrine is a challenge. The Fothergill study suggests that a cut off of 3mg is reasonable, however, further research is required.

The early administration of epinephrine is associated with higher rates of ROSC for all forms of cardiac arrest.Reference Holmberg, Issa and Moskowitz10,Reference Okubo, Komukai and Callaway11 Both ACLS and the majority of the state protocols reviewed recommend defibrillation as soon as possible and epinephrine delivery after the second shock, followed by amiodarone or lidocaine. Rhode Island changed its protocol to administer epinephrine in shockable rhythms after three cycles of CPR, defibrillation, and an antiarrhythmic. Epinephrine administration after an antiarrhythmic drug is unique to the states surveyed and of unclear significance. Although less robustly studied, amiodarone has also been associated with increased survival with earlier administration and thus this is an area of clinical equipoise.Reference Wissa, Schultz and Wilson12

Rhode Island allows for an epinephrine infusion in place of epinephrine bolus dosing. Studies to support this are lacking, but there are several theoretical benefits such as simplifying the resuscitation process and producing a more consistent serum epinephrine level. In the case of ROSC, the epinephrine infusion is already available and can be rapidly titrated to avoid hypotension. The downside is potentially increased dosing errors and time commitment to mix the infusion.

Studies have suggested that it takes on average 17 years for basic research to change clinical practice.Reference Morris, Wooding and Grant13 It is thus not surprising that only a limited number of states have changed epinephrine use in nontraumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. The changes in these states, however, may reflect the future of cardiac arrest resuscitation and provide an important framework for future research.

Limitations

This study focused on prehospital cardiac arrest resuscitation in the United States only, so it may not be generalizable to other countries. Additionally, a further limitation was the exclusion of states that did not have state-wide protocols. The states that were included did have approximately 49.4% of the 2020 population of the United States, which suggests that the studied states reflected a significant portion of the country.14 While inclusion of local and regional protocols would have allowed for a better understanding of the changes that have been made, it would have also complicated the generalizability of these findings, as jurisdictions of smaller size are able to adapt to research findings at a faster rate than that of protocols that are dictated on a state-wide level. Additionally, the authors were unable to find the 2018 protocols for several states. Since the 2021 protocols were consistent with ACLS, it was assumed that there was no change. However, it is possible that the states with missing data could have made changes between 2018 and 2021 to become congruent with ACLS guidelines. Finally, the limited number of states that instituted a change in their protocol limits drawing any definitive conclusions but does suggest potential future directions.

Conclusion

Five states have changed their cardiac arrest protocols to alter epinephrine administration from 2018 through 2021. The most frequent change was limiting the total number of epinephrine administered to either three or four milligrams. This may represent the future direction of epinephrine use for out-of-hospital nontraumatic cardiac arrest, however, conclusions are limited by a small sample size and focus on a single country’s EMS system.

Conflicts of interest

The author(s) declare none.