Introduction

As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has highlighted, disasters and emergencies from all causes can lead to a dramatic loss of human life and other impacts on people’s health. They often present substantial challenges to public health, health systems, and communities.Reference Abate, Checkol, Mantedafro, Basu and Ethiopia1–Reference Hung, Lam and Tsui5 Rising health risks associated with disasters are due to increasing risk drivers, exposures, and vulnerabilities (such as poverty, risk-exacerbating urbanization, aging societies, and climate change).Reference Allender, Lacey and Webster6–Reference Lim, Balsari and Hung11 To protect human health and reduce mortality from disasters, strategic planning and actions for disaster risk management are vital to strengthening local and national capacities and systems within and across all levels of society.12

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (Sendai Framework) placed human health at the center of disaster risk reduction.13 In response, the concept of Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management (Health EDRM) became increasingly important for applying a risk management approach to health risks associated with emergencies and disasters and ensuring that health risks and consequences are integrated into disaster risk management principles, policies, and practice.Reference Wright, Fagan and Lapitan14 The World Health Organization (WHO; Geneva, Switzerland) Health EDRM Framework was published in 2019 to describe comprehensive actions to reduce hazards, exposures, and vulnerabilities and strengthen capacities for prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery.15 It emphasized all-hazard, risk-based, people- and community-centered approaches, and highlighted ten core components comprising around 200 functions for effective Health EDRM. These components and functions reflect the wide-range of inter-related and mutually dependent capacities required for resilience-building in health systems, communities, and countries.

Health EDRM Workforce Development

The Health EDRM workforce comprises actors across the health system with a wide-range of roles and responsibilities that enable hazards, exposures, and vulnerabilities in communities to be reduced and provide the capacity for preparedness, response, and recovery for emerging and actual events. In order to strengthen this workforce to implement Health EDRM, long-term strategic planning for developing and sustaining the entire health workforce, including a focus on capacities to manage the risks of emergencies and disasters, is essential.15 There are several Health EDRM workforce strategies, initiatives, and programs available at the local, national, and global levels.16,17

The WHO Emergency Medical Team (EMT) initiative has developed a global registry system for EMTs since 2015 to promote minimum standards for surge capacity.18,19 The EMTs must undertake a quality assurance control process to prove that they meet set competencies and standards to provide quality care during emergencies. Global information-sharing initiatives, such as the “OpenWHO,” facilitate online courses and provide practical and evidence-based information on disaster-related topics, such as epidemic preparedness and response.20 Workforce management includes planning for personnel surge capacities during an emergency response, training for competency development, as well as occupational health (including the protection, retention, and deployment of staff).15

Strong, competent, and well-resourced health workforces working together across different disciplines, sectors, and levels are critical for strengthening Health EDRM programs and building systems that can effectively manage the complex nature of risks in countries and communities. Whether due to varying economic development levels, political will, availability and coverage of health workers, or the dynamic risk environment to personnel, establishing and sustaining such programs can be an immense challenge.

Health EDRM Workforce Development Research Project

In 2018, the WHO Health EDRM Research Network identified an urgent research need to address knowledge and evidence gaps in Health EDRM workforce capacity development.Reference Kayano, Chan, Murray, Abrahams and Barber21 An international research project, composed of 15 researchers and practitioners with extensive knowledge in Health EDRM, started in June 2020.Reference Hung, Mashino and Chan22 This project aimed to generate policy ideas based on practice evidence and to create important strategic recommendations for facilitating effective workforce development for Health EDRM at local, national, and international levels.

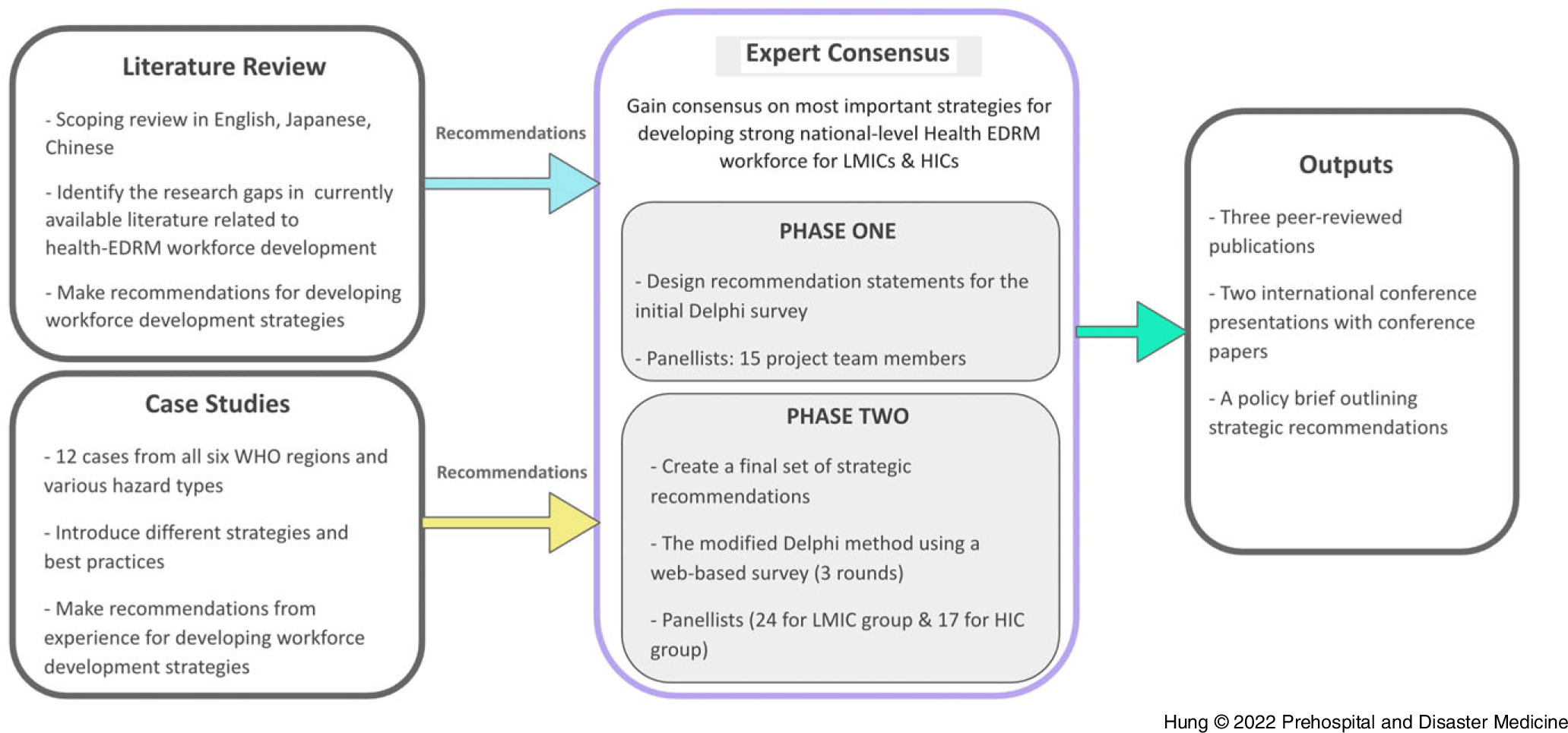

The overall project utilized multiple research methods, including a multilingual literature review, case studies, and an expert (Delphi) consensus study. The literature review identified evidence gaps and collected information on strengthening the Health EDRM workforce.Reference Hung23 At the same time, case studies were collected to illustrate best practices in existing Health EDRM workforce development. These combined sources were subsequently analyzed to create preliminary recommendation statements for the next phase of the study.Reference Wong, Hung, Mabhala, Tenney and Graham24–Reference Dalal, Singh, Gupta, Barwal, Madan, Sood and Bindal28

This paper reports the final part of the overall Health EDRM workforce development project: the Delphi consensus study. The focus of this consensus study was to identify strategic recommendations for strengthening the workforce for Health EDRM in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) and high-income countries (HIC).

Methods

Study Design

A Delphi-style expert consensus study was conducted. The study was guided by the results from a previous multilingual literature review and multiple case studies (Figure 1). Consensus on the rating of the level of importance for 46 distinct Health EDRM workforce development statements was sought from both LMIC and HIC experts. The Modified Delphi method follows a consultative process to enable a group of diverse experts to make decisions independently and anonymously without a face-to-face meeting.Reference Crowe, Cresswell, Robertson, Huby, Avery and Sheikh29–Reference Khan, Brown and Gagkiardi34 This method is commonly used to aggregate expert opinions for health policy development when available evidence is limited.Reference Keeney, Hasson and McKenna30,Reference Meskell, Murphy, Shaw and Casey31 Three rounds of surveys were conducted at three-week intervals using an iterative web-based survey Stat59 (Build 722fc5, Stat59 Services Ltd; Edmonton, Canada). Ethics approval was obtained from the Chinese University of Hong Kong (Hong Kong, China) Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee (SBRE-21-0152).

Figure 1. Flow Chart of the Study.

Abbreviations: EDRM, emergency and disaster risk management; HIC, high-income country; LMIC, low- and middle-income country; WHO, World Health Organization.

Statement Design (Phase 1)

The study consisted of two phases including statement design (Phase 1) and the Modified Delphi process (Phase 2), as shown in Supplementary Table 1 (available online only). A total of 51 preliminary statements were developed from the literature review and case study analyses. The 51 statements were distributed via a digital survey for review by researcher team members. Fourteen researchers with backgrounds in disaster and emergency medicine, nursing, and public health were asked to keep, delete, or modify each statement by focusing on each statement’s relevance as well as such elements as wording, tone, depth of information, or use of terminology. They could also suggest new statements. All results and comments from the research group were finalized for external expert rating using the Modified Delphi technique (Phase 2).

Thirty statements needed textual adjustment. Five statements were removed due to conceptual overlap with other statements. This resulted in a final list of 46 statements for the Delphi process. These 46 statements were categorized into nine core themes according to the components of the Health EDRM framework:15 Policies, Strategies, and Legislation; Planning and Coordination; Human Resources; Information and Knowledge Management; Risk Communications; Health and Related Services; Community Capacities for Health EDRM; and Monitoring and Evaluation. “Health Infrastructure and Logistics,” which includes hospitals and medical supplies, was integrated with “Health and Related Services” for better grouping.

Modified Delphi Technique (Phase 2)

The same 46 recommendation statements delineated in Phase 1 were used for separate ratings in the LMIC and the HIC groups. Expert panelists (referred to as panelist) were assigned to either the LMIC or the HIC group and each group’s processes were independent of each other. Each panelist was given access to the STAT59 software program to review all statements and were asked to rank the level of importance for each statement on a one-to-seven linear rating scale (one being strongly unimportant to seven being strongly important). In the second and third rounds, each expert was asked to rank each statement again after reviewing the mean group response score for each statement. Panelists were also given an opportunity to suggest a maximum of two new statements in an open textbox at the end of the first and second rounds of the survey.

Panelist Selection

Phase 2 panelists were selected purposefully based on their professional expertise, prior publication records, and relevant job positions in Health EDRM agencies. The inclusion criteria were: a minimum of five years of experience in a disaster risk management field, or one or more prior publications (eg, a first author or corresponding author publication in a peer-reviewed journal on a relevant topic), or relevant positions held in related institutions (eg, a member of the WHO, national disaster authority, or local government department involved in disaster risk management or health workforce development). A minimum of ten panelists were required for both the LMIC and the HIC group.

Data Analysis

The mean and standard deviation (SD) of the panelist ratings for each statement were the main measurements in this study. Consensus measurement was also a key component of Delphi analyses and data interpretation. However, there is no universal agreement on determining the level of consensus on the importance of the statement.Reference Trevelyan and Robinson33 Previous studies suggested consensus was reached if the target percentage of agreement was over 51%,Reference McKenna35 70%,Reference Trevelyan and Robinson33,Reference Sumsion36–Reference Stewart, Gibson-Smith and MacLure38 or 80%.Reference Green, Jones, Hughes and Williams39 In this study, SD <1.0 (from the mean for the statement) was the cut-off point for the level of agreement. This was because 68.2% of values fall within one standard deviation of the mean score in a normal distribution.Reference Harpe40

In the first and second surveys, recommendations with a SD <1.0 were regarded as having reached consensus and were excluded in subsequent rounds. Remaining recommendations with a SD ≥1.0 were deemed as requiring further consultation and were carried forward to the next round. During the third (and final) survey, all statements with a SD ≤1.0 were deemed as having reached consensus.

In terms of importance of the statements, the mean score of higher than five (out of seven) was regarded as important. Both the consensus and the mean scores were considered together; for example, high level of consensus on a high mean for the ratings.

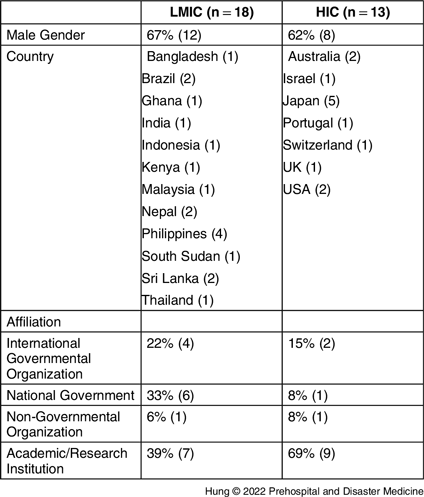

Both LMIC and HIC groupings were classified by the gross national income per capita according to the World Bank (Washington, DC USA) classification system.41 Experts were allocated to the respective groups based on their current work location. Descriptive statistics including percentages for panelist characteristics, mean (and the 95% confidence interval), and SD for the importance of the statements were used.

Results

Out of the 72 invited experts, 31 (43.1%) participated in the Delphi consensus survey portion of this study. Consent was obtained from each panelist for participation. Eighteen panelists were allocated to the LMIC group and 13 were allocated to the HIC group. Table 1 illustrates the characteristics of experts in the Phase 2 panel.

Table 1. Expert Panelist (Phase 2) Profile

Abbreviations: HIC, high-income country; LMIC, low- and middle-income country.

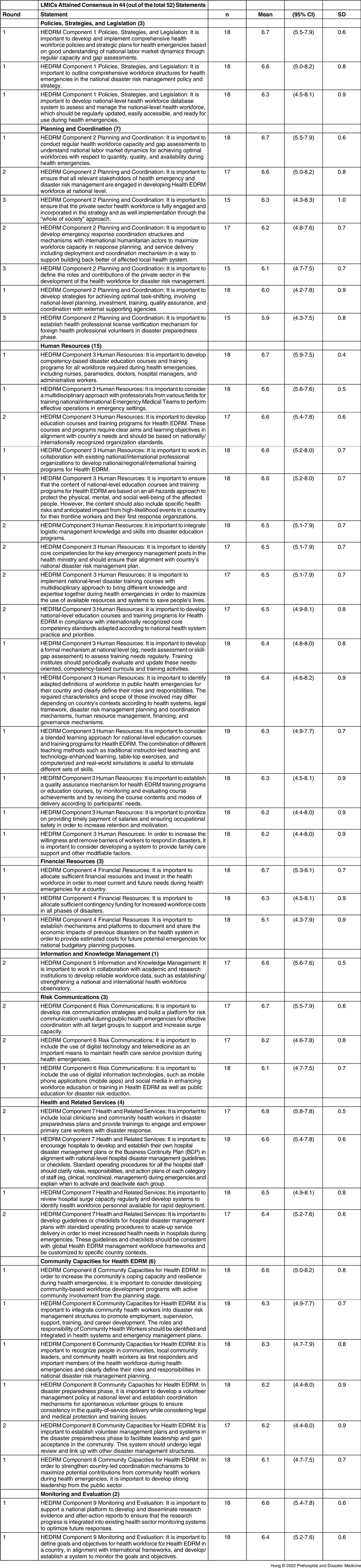

There were 18, 17, and 15 respondents in the LMIC group over the three rounds of surveys and 13, 12, and 12 respondents for the HIC group. Supplementary Table 2 (available online only) shows the results of the three rounds of surveys. Overall, 44 out of the 52 (84.6%) statements attained consensus on the rating of the level of importance in the LMIC group, and 34 out of the 53 (64.2%) statements attained consensus for the HIC group.

Table 2 describes the number of statements which had and had not attained consensus in the various Health EDRM components in the LMIC and the HIC groups. The mean score of the rating of these recommendation statements ranged from 5.9 to 6.8 (out of 7.0) for the LMIC group and 5.1 to 6.2 (out of 7.0) for the HIC group. Scores were higher overall in the LMIC than in the HIC group (mean 6.4 versus 5.7; P <.001).

Table 2. Numbers of Initial, Added, Attained, and Not Attained Statements in Each Health EDRM Component

Abbreviations: EDRM, emergency and disaster risk management; HIC, high-income country; LMIC, low- and middle-income country.

Table 3 and Table 4 provide the full list of statements that attained consensus for the LMIC and the HIC groups, along with mean scores. Statements that did not attain consensus are listed in Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4 (both available online only). The components with the highest number of recommendations were “Human Resources” (n = 15), “Planning and Coordination” (n = 7), and “Community Capacities for Health EDRM” (n = 6) in the LMIC group. “Policies, Strategies, and Legislation” (n = 7) and “Human Resources” (n = 7) were components with the most recommendations in the HIC group.

Table 3. Statements Attaining Consensus in the LMIC Group

Abbreviations: HEDRM, health emergency and disaster risk management; LMIC, low- and middle-income country.

Table 4. Statements Attaining Consensus in the HIC Group

Abbreviations: EMT, Emergency Medical Team; HEDRM, health emergency and disaster risk management; HIC, high-income country; WHO, World Health Organization.

Discussion

This expert consensus study identified strategic recommendations for strengthening workforce capacities for disasters and health emergencies in both HIC and LMIC settings. Consensus was achieved for 34 recommendation statements in the HIC group and 44 statements in the LMIC group. These strategic recommendations can be used to guide future Health EDRM workforce capacity building before, during, and after disasters. The high means on the one-to-seven linear rating scale (5.9 to 6.8 for the LMIC group and 5.1 to 6.2 for the HIC group) reflect the high level of importance accorded to all statements attaining consensus. Furthermore, there were a number of statements that did not meet the cut-off point for consensus but received a high mean score for importance. They should not be regarded as being unimportant or not needed, rather they did not reach the level of consensus as other statements.

Investing in the Health EDRM Workforce

The results show that participants felt strongly that human resource capacities and management systems are crucial to many Health EDRM functions. A risk management approach to Health EDRM recognizes that the entire health workforce has roles to play to reduce the risk and impact of emergencies and disasters. The importance to allocate sufficient financial resources and investment in the health workforce was recognized by both LMIC and HIC groups.

The WHO defined the health workforce as “all people engaged in actions whose primary intent is to enhance health.”42 This definition includes all health professionals who are essential for maintaining functional health systems, as well as workforce groups not traditionally regarded to be in the health domain, such as rescue personnel, police, and community health workers.43 To effectively manage and mobilize all available human resources with different skill sets, experiences, and knowledge, a good understanding of the wide-ranging composition of the Health EDRM workforce is necessary.

Due to the diverse composition of the Health EDRM workforce, the need for well-established models for administration and governance of systems and programs at the country level and the co-dependencies for fulfilling functions, there are intrinsic difficulties in providing a robust taxonomy for the Health EDRM workforce; for example, based on workforce groups. Several key recommendations in both the LMIC and the HIC groups emphasized the importance of health workforce capacity and gap assessments of the national labor market, developing national-level health workforce database systems, and collaborating with academic and research institutions to establish national and international health workforce observatories.

Adapting to the Local Context – Results from the LMIC and HIC Groups

Consensus was attained for 44 recommendations in the LMIC group (mean of mean scores 6.4; range 5.9 to 6.8), suggesting that most of statements were regarded as important in LMIC settings. There were fewer statements that attained consensus in the HIC group (34 statements), and those that did achieve consensus did so with a lower score (mean of mean scores 5.7; range 5.1 to 6.2).

There were also differences in the number of final recommendations by Health EDRM component. A higher number of statements attained consensus and high mean score in the “Policies, Strategies, and Legislation” and “Information and Knowledge Management” component in the HIC group compared with the LMIC group. On the other hand, in the LMIC group, there were more statements that achieved consensus and high mean score in the components of “Planning and Coordination,” “Human Resources,” “Community Capacities for Health EDRM,” and to a lesser extent, in “Health and Related Services.” These differences could be influenced by factors such as the level of national disaster risk management capacities, available financial resources, or having established professional bodies and health systems. Many HICs may already have established national disaster risk management strategies and plans, so they may have different needs when it comes to the recommendation statements included in the survey.

The fewer number of statements attaining consensus in the HIC group may have been due to larger differences in Health EDRM in HICs. It may suggest that priorities in LMIC are more systemic, with fundamental challenges stemming from their health systems compared to HICs. Workforce challenges for the Health EDRM workforce are similar to those for health systems in general (eg, availability, accessibility, employment, recruitment, remuneration, retention, and occupational health and safety). In fact, these challenges are likely to be amplified during emergencies and disasters, as the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted.44 The integration of “Health EDRM” into overall health workforce strategies is needed in many countries, but may be more needed in LMIC, judging by the statements reaching consensus.

It is interesting to note that most of the EMT statements were de-prioritized by the LMIC group but reached consensus in the HIC group. Some panelists reflected that EMTs, while being very relevant to readiness and medical response to disasters, are just a portion of the many other “teams” and “health disciplines” that form Health EDRM. This may be related to the fact that EMT initiative built on the earlier work of “foreign medical teams” that focused on support provided by HIC countries, and the concept of EMTs may not yet have been fully translated across the LMIC settings.

Integrating with a Health Systems Approach

Given current and emerging threats (such as disease outbreaks, climate-related hazards, violence, and conflict) as well as vulnerabilities (such as poverty, inequities within and between countries, lack of access to primary health care, and emergency department over-crowding), narrowing the selection of strategic recommendations was challenging. In Phase 1 of this study, the results of a literature review that evaluated strategic workforce management and drew capacity building recommendationsReference Hung23 was modified to adapt to the Health EDRM context following the “all-hazard” and “whole-of-society” approach.17,Reference Khan, Brown and Gagkiardi34 The need for the integration of these emergency preparedness efforts with a health systems approach was also highlighted in the results of this study.

Notably, the importance of risk communication strategies and establishing risk communication platforms was reflected in one of the statements attained consensus and high mean score both for the LMIC and the HIC group: “To develop risk communication strategies and build a risk communication platform for effective coordination with all target groups during public health emergencies and support and increase surge capacity.” The importance of workforce development in this area in the recent COVID-19 pandemic was also observed.Reference Généreux, David and O’Sullivan45

The recommendation to “Ensure that the content of national-level education courses and training programs for Health EDRM are based on an all-hazards approach to protect the physical, mental, and social well-being of the affected people” was also among the statements attaining consensus and high mean score for both LMIC and HIC groups. While there remained a lack of universally accepted set of core competencies for the disaster health care providers,Reference Elaine Daily and Padjen46,Reference Gallardo, Djalali and Foletti47 efforts are underway to provide common learning strategies for health emergencies programs such as in the WHO.48

Lastly, the importance of engaging and equipping the primary health care workforce and community health workers is reflected in the recommendation to “Include local clinicians and community health workers in disaster preparedness plans and provide trainings to engage and empower primary care workers with disaster response” attaining consensus in both LMIC and HIC group. This effort is synonymous with the WHO Thirteenth General Program of Work (GPW 13) and its target of achieving universal health coverage.49 A “health systems” approach is required to ensure that the fundamental elements of Health EDRM in health workforce development are addressed.

Limitations

This study had a few limitations. There are no universally agreed upon definitions of consensus for Delphi studies, and the analysis of Likert-type scales remains controversial. The one-to-seven linear scale was used in this study, which is different from Likert scale and anchored only on the extremes. The design of the one-to-seven linear scale considers that the distance between each of the numbers is equal and allow the use of parametric statistical tests.Reference Harpe40 The definition of consensus and importance using SD and mean was based on this reasoning.

There are also no set criteria on how panelists should be selected. As “experts” were not selected randomly, generalization of the results may be limited.Reference Sackman50 As the panelists in Phase 1 and Phase 2 were mostly from academic institutions, there is a risk that their ratings might have been skewed toward more academic research directions. It is important to note that consensus may have been influenced by the way in which panelists responded to the survey (depending on their levels, roles, and functions), as the understanding of Health EDRM varies across respondent groups. For example, there may have been variations in the way people at the sub-national, national, and supra-national levels responded. Panelists could also be swayed by the most recent disaster (eg, the immediacy of the COVID-19 experience may be a source of bias towards disasters associated with infectious diseases).

Required strategies in each country can vary depending on the national context (eg, level of capacities for disaster preparedness and response, political structure, available resources, disaster risks, or health systems). Each country’s strategy to develop and strengthen the health workforce for Health EDRM will depend on the national context in terms of disaster risks, available resources, experience, or governance systems. It is important to note that even though there were recommendations that did not attain consensus, these may still be important strategies for a particular country’s profile. It is also important to recall that consensus and the use of standard deviation results in a set of priorities, but that is not to say that those statements that did not reach this level of consensus are “unimportant” or “not needed.”

Conclusion

The expert panel provided a comprehensive list of important and actionable strategic recommendations on workforce development for Health EDRM. Health EDRM workforce strategies should emphasize strengthening the roles, capacities, and competencies of leaders and managers who are responsible for leading, developing, and coordinating systems and programs for Health EDRM.

Conflicts of interest/funding

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This research was supported by the World Health Organization Centre for Health Development (WHO Kobe Centre-WKC-HEDRM-K19008).

Authors’ Contributions

KH, EC, SM, SB, GC, FDC, MD, SE, BE, AH, TI, LR, HS, JW, and CG conceived of the study. KH, MM, and CG designed the study and coordinated the overall study and the acquisition of study data. KH, MM, and CG analyzed the study data, and all authors were involved in interpreting the data. KH and MM drafted the manuscript, and all authors critically revised the manuscript and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Basudev Pandey, Carlos Primero Gundran, Ngoy Nsenga, Jun Gao, Saroj Ojha, Debora Noal, Sheila Bonito, Saminda Kumara, Ina Agustina Isturini, Joseph Bonney, Olushayo Olu, Khairi Kassim, Ronald Law, Dimuthu Rathnayake, Mihir Bhatt, Elaine Miranda, Prasit Wuthisuthimethawee, Nahoko Harada, Glen Cuttance, Sae Ochi, Mayumi Kako, Onyema Ajuebor, Maria Moitinho, Naru Fukuchi, Anthony Redmond, Donald Donahue, Kristi Koenig, Tatsuhiko Kubo, and all other expert panelists for their contribution. They also acknowledge Catherine Mok’s assistance with administrative support for the Delphi survey portion of this study, and Jeffrey Franc of Stat59 for assistance with developing the study design.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X22001467