we must defend the men who live by law, never let some woman triumph over us. Better to fall from power, if fall we must, at the hands of a man – never be rated inferior to a woman.Footnote 1

I. Introduction

The legal chronicle of pop singer-songwriter Kesha Sebert has brought to light serious problems of gender and power in the US recording industry. These contemporary problems have specific historical origins. Contextualising the 2008–2014 lawsuit between two rival producers over the exclusive right to Kesha's labour power suggests that elements of Victorian gender relations and class war were baked into the doctrine on which that 21st-century case turned. These elements established terms on which the pop producers made their arguments about Kesha's obligations and on which the court understood them.

Conditions of possibility for the contractual commodification of Kesha's labour power have an origin in the 1853 English high court decision that opera singer Johanna Wagner was not an independent contractor in control of her own labour but a servant whose labour power had been purchased by London opera producer Benjamin Lumley. The decision's (re)definition of singing as labour power took the form of prohibiting Lumley's competitor Frederick Gye from offering Wagner better terms and persuading her to break her existing contract with Lumley. The Lumley v. Gye decision established the power of entrepreneurs who hire professionals to escape certain risks of entrepreneurialism. The ‘Lumley doctrine’ allows entrepreneurs to isolate valuable workers like Kesha from markets for their labour, even though, by contracting with them, entrepreneurs have ‘voluntarily exposed [themselves] to precisely the risk that someone else would lure away the contract-breaker’ (Howarth Reference Howarth2005, p. 222). A double apparatus of male and entrepreneurial supremacy, articulated in 1853, still determines the status of recording artists (and other professionals) and their labour power and is particularly visible in gendered contests.

Contracts for the sale of musical labour power have played an indispensible role in the 20th and 21st century recording industry, giving music capitalists rights over performers’ labour, for the duration of the contract, in exchange for money and other goods. The rules governing these contractual exchanges and their enforceability, the power relations of performers and those who hire them, the forms of law involved in the enforcement or protection of these contracts, and the tactics and rhetorics available to buyers and sellers in moments of conflict are durable yet continually changing factors. In popular music studies, the analysis of individual contracts for the sale of singers’ labour power (e.g. performance and recording contracts) is not as developed as are studies of music and law that focus on copyright, censorship, cultural policy or collective bargaining (but see Stahl Reference Stahl2010, Reference Stahl2013; Greenfield and Osborn, Reference Greenfield and Osborn1998). This paper aims to contribute to that development. It pursues contract questions with attention to labour power's commodification, a continuing process that began in 17th-century England and in which the 1853 London opera decision appears to play a crucial role.

The commodification of labour – its production as an item of free sale and purchase in modern markets for labour – has been revealed by historical and sociological research into English master and servant law as proceeding episodically through 18th- and 19th-century workshops, courts and Parliaments. In these settings, arguments over the obligations of weavers, potters, shoemakers and other workers to their masters led to decisions and provoked legislation that over the course of the 19th century, ‘eliminated employer obligation while yet enforcing dependence and subservience on employees’ (Fisk Reference Fisk2009, p. 79). For example, not only did most English and Welsh workers lack the right to quit once under contract, but they could be imprisoned for up to three months for doing so, and in the 1850s they could be re-imprisoned for refusing to return to work once the (first) sentence was completed (Hay Reference Hay, Hay and Craven2005, p. 59). According to Simon Deakin and Frank Wilkinson,

during the nineteenth century, the most important fault-line within employment law was not between employees and the self-employed, but between industrial and manual workers, who were subject to the master–servant regime in its various forms, and higher-level managerial, clerical and professional workers, who were outside the disciplinary reach of that legislation. (Reference Deakin and Wilkinson2005, p. 5)

Explaining why singers were outside the reach of master and servant law before 1853 is beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, the 1853 decision that Johanna Wagner was a servant like any shoemaker (Lumley v. Gye 1853, p. 759), and that her labour was an object of her employer's property, established a foundation for the advancing commodification of professional labour power, participating in ‘a massive transfer of autonomy from creative workers to their employers’ (Fisk Reference Fisk2009, p. 79).

In the late 2000s, Kesha Sebert found herself in a position similar to Wagner's as two pop producers sued each other to resolve the same question: which of them would have the right to Kesha's singing powers? Just as Johanna Wagner had done a century and a half earlier, Kesha had signed exclusive contracts with two music capitalists. Both cases embody the triangular relation of male employer–male competitor–female employee that Sarah Swan (Reference Strong and Raine2012) argues is of singular importance in the 19th-century project of labour commodification. Drawing empirically on court documents, and analytically on perspectives from history and sociology as well as feminist legal scholarship, this paper focuses on the persistent vitality of that ‘gendered erotic triangle’ (Swan Reference Swan2012) in music production. By contextualising Kesha's gendered legal triangulation, and dissecting a seemingly technical quibble about the interpretation of a statute of (temporal) limitation, this paper frames the commodification of singers’ labour power as central to a gendered project of class domination.

A few years ago, this journal published a report by Simon Frith on the 2016 Working in Music conference under the misprinted headline ‘Are workers musicians?’ (Frith Reference Frith2017, p. 111). Underpinning the enforceability of the prohibition on competition discussed here, the employer injunction, and since the early 20th century, protection of trade secrets (e.g. in the form of non-compete and non-disclosure agreements; see Fisk Reference Fisk2009), the Lumley doctrine invites us to linger with that question. To the degree that contemporary workers have to deal with employers’ rights in their talent, reputation or knowledge – contractual conditions inaugurated by a Victorian court's holding on the relationship of a singer to the entrepreneur who engaged her to sing to make money – the question ‘Are workers musicians?’ may be answered ‘Yes’.

II. Commodification, gender and a ‘long fetch’ of music profiteering

In the last 50 years or so, the dual process of commodification and control faced by performers under contract to record companies has fascinated various publics. From mass-market films and books in the 1960s and 1970s to the proliferation of the music documentary and biopic film genres and related developments in television production, accounts of pop singers at work seem to be endlessly refreshed (see e.g. Keightley Reference Keightley and Dickinson2003; Bannister Reference Bannister2017). Scholarly attention has increased in scope and coverage too. Mike Jones identifies a process of performer commodification obscured behind the ‘feel good’ phrase ‘artist development’ (Jones Reference Jones and Beck2003, p. 151). Although he doesn't use the term, subordination is perhaps the key social dynamic at work in artist development in his account. Jones presents the performer as ‘structurally disempowered’, dependent on the continuing support of managers and record companies. For Jones the critical matter is that the ‘pop act’ (2003, p. 148) – the performer(s) – must adapt themselves to the various demands of these other participants; these demands touch on the act's artistic style, self-presentation and so on. Acts who fail to meet such demands are likely to be sidelined or dropped as those parties instead prioritise more tractable acts. Jones illuminates relations of power in the commodification of musical work in the recording industry, arguing that aspiring pop stars are ‘rendered vulnerable by their very desire for success’ (2003, p. 155), insisting that performers themselves, and not (only) their capacity to labour, are subject to commodification in the ‘artist development’ process.

Yet the vulnerability of aspiring pop acts (and established pop stars) also has a legal basis: the contract by which the company can insist that the act must do this or must not do that, where the punishment for failure to comply can include indefinite professional isolation, not just being dropped by the company. As Greenfield and Osborn (Reference Greenfield and Osborn1998) show, the standard recording contract gives the company the power to keep the act under obligation, without legal access to a market for their labour, indefinitely. It was exactly this professional detention that awaited Kesha in 2014 when she sought to end her contractual relationship with producer Dr. Luke, and in which she spent several years unable to offer her services to anyone else.Footnote 2

Gender hierarchy has long featured in commonsense understandings of the social relations of opera. When (around 1862) Marx wrote about singers as productive workers, he identified the singer as female.

A singer who sings like a bird is an unproductive worker. If she sells her song for money, she is to that extent a wage labourer or merchant. But if the same singer is engaged by an entrepreneur who makes her sing to make money, then she becomes a productive worker, since she produces capital directly. (Marx Reference Marx and Fowkes1977, p. 1044, original emphasis)

By the time Marx wrote this passage he had lived in London for about 10 years; as a consumer of news he could not have avoided the continual coverage of prima donnas’ doings and theatre managers’ travails in the Times of London and other publications. He does not specify the gender of the entrepreneur, but I think we can be certain it would have been male.

Research into the social relations of capitalist recorded music production since Jones's important contribution has had much to tell about how gender formation deepens and complicates the experience of commodification and intensifies the vulnerability of female acts. ‘Men dominate every facet of the music industry, monopolising both the creative and production sides, and replicating gender relations in wider society’ (Connell and Gibson Reference Connell and Gibson2003, p. 212). This gender formation persists; activism and research reveal how little has changed in the last two decades. The male supremacy of the 21st century recording industry is demonstrated in a recent study by Stacy Smith and several coauthors. The authors’ headline findings come from their analysis of credits across a sample of 700 songs featured on Billboard charts 2012–2018: women made up 17.1% of performers, 12.3% songwriters and 2.1% of producers (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Choueiti, Pieper, Clark, Case and Villanueva2019). Smith et al.'s Inclusion in the Recording Studio also involved interviews with 75 female songwriters and producers who discussed encountering gender-related career-impeding obstacles and judgments. Marion Leonard's (Reference Leonard, Warwick and Adrian2016) study found similar obstacles confronting female behind-the-scenes music industry professionals in the UK music industries.

Helen Reddington (Reference Reddington2018) and Emma Mayhew (Reference Mayhew, Whiteley, Bennett and Hawkins2004) examine the skewed power relations typical in cases where female singers work ‘with’ male producers. Reddington argues that the relation often takes the form of ‘ventriloquism’, whereby composer-performers even as formidable as Beyoncé can be characterised as ‘mouthpieces’ of powerful male producers (Reddington Reference Reddington2018, p. 62). (The term ‘producer’ has come to signify not only sound-recording production but also songwriting; this is crucial to Reddington's argument and is a factor in understanding Kesha's experience with Dr. Luke.) Mayhew's insights address a broader problem: the over-attribution of authorship and authority to men involved in music-making by women, of which ventriloquism is a category or example. According to Mayhew, ‘there is an obvious relationship between the role of the producer and the more abstract role of musical author or composer. For female performers their artistic status is often put under scrutiny in relation to the role of the producer and the issue of musical control’ (Mayhew 2004, p. 152). Singer Kathleen Hanna unambiguously links gender authority and music profiteering:

If I, as a performer, accept the idea of ‘image’, [not only in terms of commercial pressures but also male fans’ demands that she conform to their expectations] basically what I'm doing is accepting objectification of myself and allowing my work to become an easily digestible commodity … a commodity to be consumed and shat out, just like any other capitalist product. (Hanna Reference Hanna, Kelly and McDonnell1999, p. 124, original ellipsis)

Catherine Strong and Sarah Raine's introduction to Gender Politics in the Music Industry, a special issue of the IASPM Journal, proposes that ‘in order to understand how gender inequality persists in the music industry, it needs to be placed in the context of changing work conditions and the rise of the creative industries as a framework through which artistic work is often viewed’ (Strong and Raine Reference Strong and Raine2018, p. 3). This paper aims to do that, invoking what George Lipsitz might call a longish historical ‘fetch’. ‘Recorded music’, Lipsitz writes, ‘has its own dialogic currents, its own hidden histories of affiliation and identification, its own long fetch that connects it to other kinds of histories’ (Lipsitz Reference Lipsitz2007, p. xxiii). Interactions of gendered social formation and the commodification of (musical) labour show up in opera history. In the case of 19th-century London opera, significant evidence of ‘affiliations and identifications’ appears in cultural conceptions of prima donnas and as the joint efforts of male entrepreneurs, composers, critics and other participants to subordinate women performers.

The commodification of femininity in mid-19th-century music enterprise turned more on skills and reputation than on appearance. Historians of opera largely agree that prima donnas’ value came first from their ‘vocal and acting skills, only in the most marginal way by physical attraction’ (Rosselli Reference Rosselli1992, p. 68). A concern for respectability seems to have presented singers and producers with a razor's edge of reputation management: ‘the singers’ willingness to provide pleasure for money – and pleasure of a particularly sensual kind, often requiring physical display – trod a path only a step away from that of the courtesan’ (Rutherford Reference Rutherford2006, p. 189). Victorians often understood prima donnas’ ‘powers of voice, music, knowledge, sex and pleasure’ through the image of the siren, articulating their irresistible singing with the exceptional, threatening publicness of their stage performances (Rutherford Reference Rutherford2006, p. 36). The term ‘siren’, Rutherford writes, ‘retained … associations with an unfettered eroticism, but unlike “prostitute” or “whore”’ – other designations for women whose out-of-placeness threatened the gendered Victorian social order – ‘it could be used in polite (that is, public) discourse’ (2006, p. 42). The Illustrated London News disseminated coverage of London opera to its large general readership; stock descriptors for prima donnas included ‘beauty, charm, delicacy, elegance, grace, refinement, simplicity, and, most important, intelligence and expression’ (Marvin Reference Marvin, Cowgill and Poriss2012, p. 25). ‘For the most famous singers’, writes Roberta Marvin of the News's coverage, ‘the comments go further, bringing a singer's biography – genealogy, social class, breeding and education, patrons and protectors, general lifestyle, and ethnicity – to the fore’ (Marvin Reference Marvin, Cowgill and Poriss2012, p. 25). Nevertheless, reading between the lines of primary sources, Rutherford argues that ‘sexual harassment and intrigue undoubtedly existed’ and that ‘there are plenty of allusions to the pressures for sexual favours’ promised to wealthy and connected opera buffs (Rutherford Reference Rutherford2006, p. 191).

One arena of contest between prima donnas and male authorities is especially relevant to this study. Hilary Poriss's analysis of ‘aria insertion’ by 19th-century singers of Italian opera offers an example of female power in relation not only to male producers (impresarios were often referred to as producers or directors of opera companies) but also to composers, critics and other figures of high-cultural male supremacy in the middle of the 19th century. Aria insertion was the practice whereby singers swapped out arias in the score of the opera they were performing for ones that would show off their talents more comprehensively. According to Poriss, aria insertion involved singers’ authorship and control at numerous levels, it ‘entailed [the singer] searching for music that accommodated the singer's voice, but that also conveyed the “expressive self” of both the prima donna and the character she portrayed’ (Poriss Reference Poriss2009, p. 63). By around 1848, efforts by male composers and impresarios towards authorial and workplace control – as well as increasing critical denigration – had begun actively to cut against the practice; by the 1870s, contract clauses explicitly regulating or prohibiting aria insertion became the norm (Poriss Reference Poriss2009, p. 23).

In Susan Rutherford's view, aria insertion was one of several practical opera-company arenas for the suppression as well as the exploitation of women's power. For example, Rutherford examines the increasing elevation of the written score (as the anchor of aesthetic and other kinds of value) over the singers’ performances, coinciding with the incorporation of musical scores into copyright law. In this new world of opera, ‘the composer was no longer a commercial purveyor of melodies (Rossini) but refashioned as an Artist ([Richard] Wagner)’ (Rutherford Reference Rutherford2006, p. 178). Also around this time, opera companies began to introduce the ‘conductor as tyrant’ whereby ‘control of time, perhaps the musician's and especially the singer's most prized commodity in the shaping of performance, was handed to the conductor’ (Rutherford Reference Rutherford2006, p. 178). Rutherford also examines struggles between singers and producers over contracting norms (under the heading of convenienze) which ‘marked out [singers’] status: a series of professional codes concerning billing, roles, fees, privileges and so forth. Variations on these codes had been in existence from the beginning of opera’ (Rutherford Reference Rutherford2006, p. 163), and in the 1830s and 1840s, these clauses become another site of gendered contest. In sum, Rutherford identifies the mid-19th-century ‘construction of a series of controls and brakes on previous operatic practice as a kind of “masculinization” of the system of production, in which the development of “order” and “rationalization” is equated with progress and the needs of a modern marketplace’ (Rutherford Reference Rutherford2006, p. 179; see also Zechner Reference Zechner2017).

Opera historians Poriss and Rutherford foreground situations where singers contended over concrete matters of control and commodification with those producers, composers and critics who depended on the commercial and cultural value of singers’ labour power. Poriss's and Rutherford's work contributes historical and analytic insight suitable for a long-fetch examination of Kesha's legal position, at least in part because the contours and elements of such contests have changed so little in certain key respects. Their research provides a useful bridge to studies of gender and the commodification of labour that arise in the context of legal theory and history, and that illuminate music's mutually transformative entangling with law in the Anglo world.

III. Lumley v. Gye and the commodification of professional labour power

Kesha signed an exclusive contract with the producer known as Dr. Luke in the fall of 2005. She was 18 years old. Dr. Luke seems not to have prioritised Kesha to her satisfaction and so, in early 2006, she signed a second exclusive contract with David Sonenberg (doing business as DAS Communications). Of course a person cannot lawfully sell exclusive rights to their labour power to two separate capitalists, and shortly thereafter Sonenberg and Dr. Luke sued one another over which of their claims was rightful. The court integrated the suits so that they could be heard together. Judge Melvin Schweitzer wrote that the case ‘involves claims by two performing artist management agents, each of whom alleges that their respective contracts to represent a vocal artist was interfered with by the other agent’ (DAS Communications, Ltd. v. Sebert 2011, p. 1Footnote 3). Each of the two entrepreneurs charged the other with tortious (i.e. wrongfully injurious) interference with contractual relations. This form of injury – the tort of interference – is a product of this case's triangular operatic ancestor Lumley v. Gye, in which Benjamin Lumley (proprietor of Her Majesty's Theatre) sued Frederick Gye (proprietor of the competing Royal Italian Opera) over which of them had the exclusive right to the singing powers of Johanna Wagner. Wagner had signed a contract first with former, and then a second one, for more money, with the latter.

The rivalry over Johanna Wagner may have had less to do with her virtuosity than with Benjamin Lumley's commercial tactics. The producer's aggressive style of hype is exemplified in his announcement of a coming ‘premiere of Mendelssohn's The Tempest, despite the fact that the opera did not exist at the time, and indeed never came to exist in the future’ (Zechner Reference Zechner2017, p. 114). Of Wagner herself the English primary sources tell us little that does not come from the impresarios who sought to exploit her, the journalists covering the London courts, or the critics and wags more interested in the London opera scene than in its foreign performers. It is agreed that Johanna Wagner was tall. Further contemporary descriptions are so shot through with sexism, anti-German sentiment and resentment about her role in ‘the harassing season of 1852’ (Lumley Reference Lumley1864, p. 351) that it is difficult to glean much about her. Ingeborg Zechner has studied the German primary sources; from her we learn that Wagner ‘enjoyed great success in Berlin’ before travelling to London in 1852. Yet ‘this success may not have been primarily a result of her vocal accomplishments’ because Wagner ‘was more or less self-taught’, only commencing singing lessons after her first performances (Zechner Reference Zechner2017, p. 120). One contemporary German critic cited by Zechner opined that Wagner's singing exhibited ‘considerable weakness’ and that she ‘was unlikely to have a long career’ (Reference Zechner2017, p. 121). Lumley hired her to sing at Her Majesty's Theatre in 1856. He later recalled that ‘a few hisses, it is true, on her first night, testified that all recollection of the outrage of the past had not been wholly swept away’ (Lumley Reference Lumley1864, p. 381). Leah VanderVelde notes that ‘it is acknowledged that Johanna Wagner never regained the acclaim in England that she would have enjoyed by performing earlier. Four years had passed by the time she was able to make her London debut, and tastes had changed’ (VanderVelde Reference VanderVelde1992, p. 841). ‘As a concert singer’, Lumley wrote, Wagner ‘never obtained any great popularity in England’ (Reference Lumley1864, p. 384).

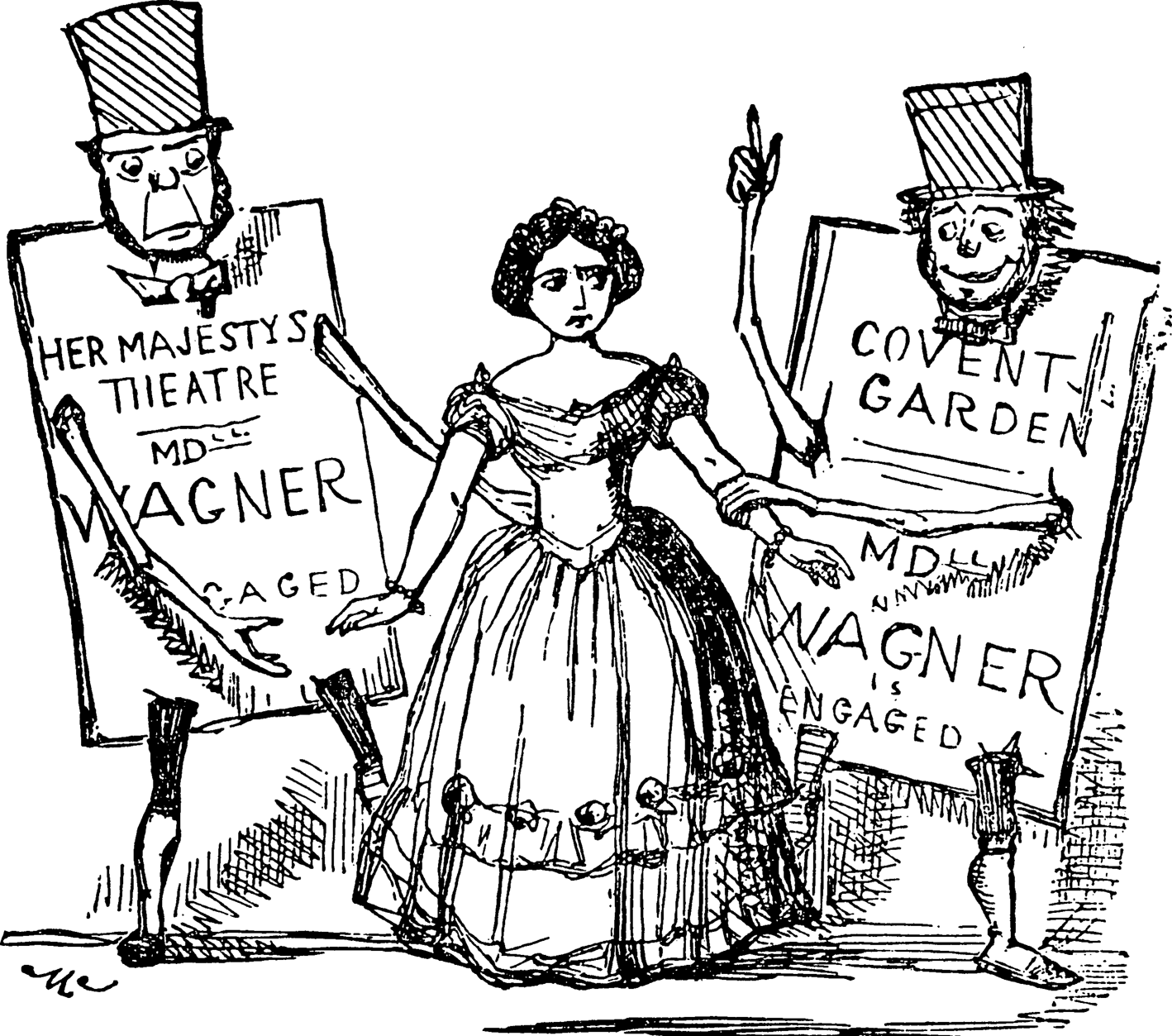

Figure 1. Punch lampoons Lumley and Gye's rivalry (1852–53, p. 185).

Lumley v. Gye may be unfamiliar to popular music scholars, but its importance in Anglo-American law seems undisputed. Considered ‘a chestnut of first-year contract classes’ (Linder Reference Linder1989, p. 71), the decision settled the dispute between the rival opera impresarios. By a majority of three justices to one, the Court of Queen's Bench found that Wagner was Lumley's servant and that Gye had committed a wrong by contracting with her to sing for his Royal Italian Opera instead of Lumley's Her Majesty's Theatre. A mountain of law scholarship, amassed since the turn of the 20th century and continuing to grow, attests to Lumley v. Gye's continuing relevance. Despite their antagonistic interpretations, The Lumley doctrine's exponents and opponents generally agree on the scale and significance of its consequences.

According to Mike Macnair, the tort of interference ‘effaces the distinction between property rights, which bind everyone not to interfere with them, and contracts, which are merely private agreements between individuals’ (Macnair Reference Macnair2011, p. 68). By making a person's labour power into a property over which an employer can exercise exclusive rights, the Lumley doctrine undergirds the presumptive illegality of unions in Britain; ‘organising strikes has [long] been said to be tortious as “inducing breach of contract” or “interference with trade by unlawful means”’ (Reference Macnair2011, p. 55). British unions, he argues, are ‘merely protected from liability’ to charges of interference by various statutes; entrepreneur's property right in workers’ labor power is fundamental, just restrained by statute (Reference Macnair2011, p. 55, original emphasis). The laws built on and rationalised by the Lumley decision, he argues, exemplify ‘a fundamental choice’ between (on the one hand) ‘capitalism and the rule of law’ and (on the other hand) ‘political democracy and free association’ (Reference Macnair2011, p. 81), and they extend far beyond employment relations (see e.g. Wilson and Pender Reference Wilson and Pender2017). In Macnair's view, Lumley v. Gye is indispensible to capitalism and the rule of law as currently administered – as ‘dictatorship of the bourgeoisie’ – in the UK (Macnair Reference Macnair2011, p. 51).Footnote 4

The US consequences of this decision have been similarly vertiginous. According to Catherine Fisk, ‘the shock of the American adoption of the Lumley doctrine’ in the 19th century ‘was that skilled, independent, and professional workers could be compelled not to quit’ (Fisk Reference Fisk2009, p. 162). ‘Indeed’, she writes, ‘the freedom to quit, even in breach of contract, was what free labor meant for white workers’ at that time (2009, p. 162). Bringing male supremacy into sharp focus, Leah VanderVelde writes that ‘the Lumley rule's reception in the United States was facilitated by the fact that the majority of cases that employers won were cases involving women’ (VanderVelde Reference VanderVelde1992, p. 777). While the doctrine remained largely uncited in the UK for decades, it proliferated more readily in the US. At first it was invoked by male employers of female performers in the worlds of opera and music hall, unsuccessfully in the 1860s and with increasing success beginning in the 1870s. In the sharecropping system of the post-Civil War US South it became instrumental in entrepreneurs’ control of formerly enslaved workers, and then in suppressing union organising activities in the late 19th century. Later, through a series of cases concerning male baseball players in the early 1900s, a juridical assumption of entrepreneurial supremacy began to encompass a widening range of employee groups (see VanderVelde Reference VanderVelde1992 and Swan Reference Swan2012 for more on these developments).

In mid-19th-century England, the relation of service (what we now generally think of as employment) gave masters (employers) the power to have their workers arrested and imprisoned. When questions of status arose, it was advantageous for masters, as buyers of labour services, to get courts to define the sellers of those services as servants and not as independently contracting professionals (Steinberg Reference Steinberg2003; Steinfeld Reference Steinfeld2001). (Masters could be charged under master and servant law too, but while servants were subject to criminal penalties, violations by masters were not criminal but civil matters.) Should Wagner have been understood by the Court of Queen's Bench as an independent-contracting professional, Lumley would not have had a case against Gye. The contract for the sale of professional services (between Wagner and Lumley or between Kesha and Dr. Luke) presupposed the formal equality of the two contractors; this relation is spelled out in the second of Marx's three conditions (above) whereby the wage labourer is the equivalent of a merchant: the seller of a job of expert work rather than the seller of a right to command obedience. Declaring Wagner a servant invalidated that civil equality.

Before Lumley v. Gye, singers like Johanna Wagner and other professionals had been understood as people one would hire to perform their expert services and not to obey commands. As civil equals, if they failed or refused to fulfill a contract, the hiring party was entitled to sue for money damages, as is generally the case in civil matters. However, after suing Wagner for breach (Lumley v. Wagner 1852), Lumley charged Gye with ‘enticement’ (which was then known also by the rough synonyms ‘procurement’ and ‘seduction’; see e.g. Lumley v. Gye 1853, p. 765). The charge of ‘enticement’ against a competitor only applied where the enticed worker was a servant and not an independent contracting professional. In taking up his case, the Court of Queen's Bench set itself the task of determining Wagner's status: it declared her Lumley's servant. As John Nockleby writes, ‘by labeling an opera singer a servant, a court for the first time broadened the action of enticement to include an impersonal employment contract between parties of equal status’. Thereafter, ‘the meaning of servant was no longer limited to employment relationships that were domestic, personal, and paternalistic’ (Nockleby Reference Nockleby1980, p. 1523). The meaning of servant – and that category's legally objectifying tendency – had crossed the longstanding cordon separating independent contracting professionals from the realm of servility and dependence, a realm where rights of control and rights of ownership are not easily distinguished.

Nockleby's phrase ‘meaning of servant’ raises a contextual question not generally addressed by the legal- or music-historical scholarship. Labour law history and economic sociology show that mid-19th-century England was in the throes of class war involving (among other things) the political franchise; the scope of penal sanctions for workers under master and servant law; poor relief, imprisonment and transportation to the colonies for debt and vagrancy; and trade protectionism favouring aristocratic landowners (see, e.g. Hay Reference Hay, Hay and Craven2005; Steinfeld Reference Steinfeld2001; Steinberg Reference Steinberg2003; Zechner's Reference Zechner2017 exceptional study of London opera discusses trade policy in relation to opera companies’ competition). The secondary sources show that at least three of the four Court of Queen's Bench justices who ruled in Lumley v. Gye had previously ruled on cases under master and servant law (e.g. Steinfeld Reference Steinfeld2001). The justices would all have been aware of 1843–1844 Parliamentary debates about master and servant law, as well as working class movements for its reform, and for political reform in general, and not least the recent defeat by state forces of Chartism, an English variant of continental revolutionary struggles that peaked in 1848.

Other sources show that rates of arrests, prosecutions and convictions of workers under master and servant law only increased in the years following Lumley v. Gye (Steinfeld Reference Steinfeld2001; Hay Reference Hay, Hay and Craven2005). It was in 1857 that the Court of Queen's Bench decided that a worker who had served his sentence could be resentenced without a new trial if he refused to go back to work for the employer that had him charged in the first place (Hay Reference Hay, Hay and Craven2005, p. 59). Douglas Hay writes that ‘the greatest number of master and servant prosecutions occurred between 1871 and 1875’, concluding that the ‘penal regime of master and servant that was created by the expansion of prisons, policing, and hard labor in the early nineteenth century continued almost until the very end’ – until the repeal of master and servant law in 1875 in response to overwhelming worker demands (Hay Reference Hay, Hay and Craven2005, pp. 108–9). Master and servant law ‘disciplined low-wage rural workers and sustained class relations on the land. It held skilled industrial workers to their contracts when demand for their labor was rising, crippled strikes, and supported employer authority in all its dimensions’ (Hay Reference Hay, Hay and Craven2005, p. 116); it was an active terrain of Victorian class war at the moment Lumley sued Gye.

For Lumley to assert that Wagner was a servant, and for that assertion to be affirmed by the court in its recognition that Gye was a legitimate target for Lumley's claims, was to translate a potentially unpredictable argument between contracting equals with rights against each other (entrepreneur and singer) into a stark matter of property as a right against all others (entrepreneur and competitors). A successful charge of enticement establishes (or recognises) the first employer's property right in the worker's labour power. The doctrine of enticement commodifies the worker because it frames and treats her labour power effectively as a piece of the employer's property. In Sarah Swan's words, the tort of interference

treats the original promisee [i.e. Lumley or Dr. Luke] and the new promisee [Gye or Sonenberg] as competitors for the same economic good, but in so doing, it ignores the fact that the ‘economic good’ in question is often someone else's labor. Through its structure, the tort commodifies the original promisor and her labor, and this commodification eclipses the personhood of the original promisor such that the tort can be used in ways that conflict with her autonomy and freedom of contract, as well as her ability to control her own labor. (Swan Reference Swan2012, p. 193)

The successful charge of enticement establishes (or recognises) that the competing entrepreneur (Gye or Sonenberg) was the agent responsible for the (worker's) violation of the contract. This classification ‘eclipses the personhood’ of the worker in its classification of her as a medium through which the competitor can injure the first employer.

In 1853, Benjamin Lumley sued rival theatre manager Frederick Gye on three counts: first, for ‘procuring [Wagner] to break her contract and not to perform or sing at plaintiff's theatre’; second, for procuring her ‘to continue away during the term for which [she] was engaged’. The third count began with a short preamble in which Lumley averred that Wagner ‘had engaged with [Lumley] to be, and had become and was, his [Lumley's] dramatic artiste for a certain term’, and charged that Gye had ‘procured her to depart out of her said employment during the term’ (Lumley v. Gye 1853, p. 749). The Court of Queen's Bench addressed the charges of ‘procuring’ as alleging acts of ‘enticement’. Three of the four justices – Crompton, Erle and Wightman – found in favour of Lumley, holding that ‘the counts were all good’; the fourth, Coleridge, disagreed, asserting that ‘the counts were all bad’ (1853, p. 749). The majority repeatedly reiterated the proprietary language Lumley used in his complaint, referring to Wagner as an ‘artiste of the plaintiff’ and ‘his dramatic artiste’ (e.g. 1853, pp. 752, 759; emphasis added).

In modern law, the power of one entrepreneur to prevent a competitor from hiring a person under contract to the former takes the form of a property right. As Kesha reportedly told her mother after signing with Sonenberg's company, Dr. Luke ‘just called me and I have 24 hours to fire my [new] lawyer and my managers and go back with him. Any time I get a contract [offer], he's going to come forward and basically say he owns me’ (Bacher Reference Bacher2016). In the context sketched by this paper, Kesha's use of property language is descriptive as much as it is inflammatory: the tort of interference gives Dr. Luke an effective property right in Kesha's labour (power) against rivals like Sonenberg. If a person cannot convey her labour to an employer except through embodied and/or conscious activity, then a property right in a person's labour is not readily distinguished from a property right in that person (Pateman Reference Pateman1988).

IV. Dr. Luke, DAS and Kesha: a ‘gendered erotic triangle’

The lawsuit between David Sonenberg's DAS Communications and Dr. Luke over the exclusive right to Kesha's singing powers is the focus of the remainder of this paper. This 2011 suit has been overshadowed by a later case that received much more attention: Kesha's suit against Dr. Luke and his counter-suit against the singer and her mother, Pebe Sebert. In that 2014 case, Kesha sought to be released from her contract with the producer, accusing him of sexual harassment; Dr. Luke immediately counter-sued Kesha for breach of contract and sued Kesha and her mother for defamation. Kesha's battle for freedom from her producer sparked ‘Free Kesha’ activism among fans and supporters, including public statements by other celebrated pop singers and Taylor Swift's public pledge of $250,000 toward Kesha's legal costs. Dr. Luke's property right in Kesha's singing labour power prohibited her from offering her services to anyone else as long as the contract endures; her idleness was enforced for three years, until she, Dr. Luke, and Sony (to whom Dr. Luke was contracted to supply recordings by Kesha) came to an arrangement allowing Kesha to record with a different producer.

In explaining core problems identified in this better-known Kesha–Dr. Luke contest, Nikki Breeland observes that ‘sexually-based offenses within the entertainment industry uniquely affect women and imprison them within contract clauses. Moreover, courts allow these women to remain victims of contractual relationships with their abusers’ (Breeland Reference Breeland2018, p. 139). Breeland argues that remedies for employees in non-entertainment sectors should be available to singers. Chanel Chasanov looks outside employment law to tenancy. In California, state law allows a renter to get out of a lease if remaining in the lease would make the renter vulnerable to sexual assault, domestic violence or stalking. Chasanov argues that ‘if a state is willing to allow individuals out of their [contractual] leases for instances of sexual assault, then it should follow that musicians should be let out of their contract for the same detrimental act’ (Chasanov Reference Chasanov2017, pp. 76–7). Kesha's situation identifies some real gaps in workers’ protection from gendered mistreatment.

The problem of male supremacy stands out starkly in this later, more famous case. By comparison, the earlier tortious interference suit between Dr. Luke and David Sonenberg seems aridly technical. It is my contention that this earlier case more clearly reveals the dead hand of 19th-century gender and class projects. One of the most significant differences between Lumley v. Gye and DAS v. Sebert is this: what was novel (and, at least to the dissenting justice, controversial) in that earlier case is without controversy in the early 21st century – a professional singer is effectively an asset over which legal subjects compete. In the remainder of this paper I examine some aspects of the rival pop producers’ contest and draw further on VanderVelde (Reference VanderVelde1992) and Swan (Reference Swan2012) to foreground gendered features of the commodification process posited above.

In September of 2005, in search of an unknown-yet-promising female pop singer to take his hits into the charts, songwriter and producer Dr. Luke signed Kesha. He told Billboard how signing her could advance his music publishing career: ‘I can control the song a bit more by producing it’ as well as writing it; ‘the next evolution of that [principle] was just to find an artist’ through whom he could control the song to his satisfaction (Werde Reference Werde2010; see also Seabrook Reference Seabrook2015). By signing with Dr. Luke, Kesha granted the producer exclusive rights to her singing services and to the use of her name and likeness for marketing purposes. In exchange, he agreed to advance her a sum of money (to be recouped out of her royalties), to supply her with songs, to produce and record her demos, and to ‘seek a new exclusive recording agreement with a Major Label’ (Agreement made as of 26 September, 2005 2005, p. 1). The 2005 contract stated that if he succeeded in pitching Kesha, ‘then such Major Label Recording Agreement shall be entered into upon the terms and conditions contained herein’ (2005, p. 1) – the terms and conditions that take up the 2005 agreement's remaining 18 pages, amounting to an abbreviated version of the standard option-based recording contract.

In early 2006, frustrated by not getting enough work with Dr. Luke, Kesha sought to be free of her obligations to him. Kesha repudiated their contract by means of a letter from her attorney and signed a new contract with DAS Communications, the business name of producer David Sonenberg. Kesha was soon informed by Dr. Luke's attorney that she was in breach of their contract: neither the contract nor the law gave her the right to ‘repudiate’ the contract. At this point, both Dr. Luke and Sonenberg claimed the exclusive right to Kesha's recording services.Footnote 5 By late 2008, Kesha had changed her mind about working with Sonenberg, choosing to return to Dr. Luke. The two amended their (still-valid) 2005 contract and began to work together on songs the latter produced and recorded. During this period Dr. Luke employed Kesha as an uncredited (but distinctive) background vocalist on Flo Rida's 2009 Billboard No. 1 Hot 100 hit song ‘Right Round’ – Kesha's ‘breakthrough’, according to John Seabrook (Seabrook Reference Seabrook2015, p. 270).Footnote 6

In 2010, this professional triangle – two male rival employers, one female performer – became a legal one as its participants initiated a series of lawsuits and countersuits. Sonenberg initially sued Kesha as well as Dr. Luke, but the battle between the producers emerged as the substantive matter. Sonenberg and Dr. Luke were not just competitors, they were rivals, and the right to Kesha's labour power seems not to have been their sole concern. Dr. Luke counter-sued Sonenberg and, as I noted above, the court integrated the two suits and declared that tortious interference – the contemporary name for enticement (procurement, seduction) – was the issue to be argued.

Lumley's mid 19th-century contest with Gye over Johanna Wagner established a novel frame for judging and regulating the relationships of professionals and their employers. Of the mix of conceptual resources readily available to entrepreneurs, attorneys and courts at the time, those having to do with gender seem to have been most ready-to-hand and consequential. Leah VanderVelde argues that ‘nineteenth-century women performers were less likely [than men] to be viewed as free and independent employees’; women were ‘generally perceived as relationally bound to men’ and ‘women performers were more likely to be perceived as subordinate than were their male counterparts’ (VanderVelde Reference VanderVelde1992, pp. 778–9). Indeed, under coverture, wives were ‘disabled from self-ownership and control of their own energies and services’ and married singers’ husbands signed their contracts (1992, p. 775). For the court, Wagner's gender identity seems to have trumped the legal subjectivity presupposed by Lumley's suit against her.

Sarah Swan (Reference Swan2012) sees in Lumley v. Gye a 19th-century gender politics that also stood out in a literary theme popular at the time: the ‘gendered erotic triangle’. Swan argues that the ‘male employer–male rival–female employee’ formation embodied in the Lumley–Gye–Wagner triangle invoked then-current notions of masculine honour and aroused gendered sentiments and commitments in the justices, journalists and others (Swan Reference Swan2012, p. 181). Gye's injurious act of procurement (seduction, enticement, interference) involved what Swan calls ‘impermissible competition’ – ‘a potentially dangerous challenge to another man's masculinity’ (2012, p. 183). In Swan's view, gendered practice and discourse, literary representation and litigation had set the terms on which Lumley and Gye's contest would be interpreted and adjudicated. As in the ancient idea of paterfamilias, the male head of household, workshop or capitalist opera company was the one injured or offended when a rival or competitor ‘interfered’ with his wife, child or (singing) servant.Footnote 7 US courts’ embrace of the Lumley rule sounded this same note. Even though ‘legal formalism, legal preferences for capital over labor, and class stratification were all at work in the late nineteenth century’, VanderVelde argues, it was ‘gender discrimination [that] created the pathway for the adoption [by the Lumley court] of a more regressive legal rule’ (VanderVelde Reference VanderVelde1992, p. 850). According to this rule, the employer of a professional has a property right in that professional's obligation to work, which transforms the object of their exchange into commodity labour power.

Dr. Luke's legal filings characterise Sonenberg's ‘desire to harm’ in ways that smack of the gendered indignation legible in both Lumley v. Gye and the later US cases against female performers examined by VanderVelde and Swan. The following excerpts paint a fervid picture. In one of Lukasz ‘Dr. Luke’ Gottwald's submissions to the court, Sonenberg's ‘longstanding and simmering personal animus’ towards Gottwald was said to derive from Gottwald's rejection of ‘Sonenberg's aggressive overtures and advances years prior to act as Gottwald's personal manager’ (Gottwald Reference Gottwald2011, p. 2). As Sonenberg ‘watched Gottwald's star rise, [he] seethed with hostility’; in signing Kesha, Sonenberg had ‘seized upon [an] opportunity to exact his revenge … by ruining [Gottwald's] relationship with Kesha’ (2011, p. 2). Dr. Luke asserted that it was only when Kesha ‘resumed her rightful relationship with [him] that her star rose’ (2011, p. 2, emphasis added).

Dr. Luke's use of ‘rightful’ may be within norms of legal argument, but in this context it is redolent of the patriarchal rights of fathers, masters, and husbands (see Pateman Reference Pateman1988). VanderVelde tells us that at the time of Lumley's suit against Gye, the charge of enticement (seduction, procurement, interference) was closely related to divorce proceedings:

The cause of action to protect an employer's interest in his employee was virtually identical to the cause of action to protect a husband's interest in his wife's services. In England, the first step in obtaining a divorce was an enticement action against the third-party interferer, a suit that was identical both in name as well as form to the enticement action that employers could bring against rival employers. (VanderVelde Reference VanderVelde1992, p. 833)

Even more striking, ‘advertisements for runaway wives were posted in newspapers next to those for runaway slaves and apprentices’ (VanderVelde Reference VanderVelde1992, p. 834). In the 19th century, Swan notes, the ‘same word, “master”, referred both to husbands and employers’, reflecting the fact that ‘the line between husband and employer was linguistically, culturally, and legally blurred, and female performers were seen as quasi-wives, subject to the will of their employers’ (Swan Reference Swan2012, p.187). As a woman, Johanna Wagner was already so much like a wife, daughter or apprentice that the Court of Queen's Bench subsumed her professional identity and status under the category of dependent subordinate, an extension of her master's private property.

Gottwald highlights his management, cultivation and administration of Kesha and her career – key terms in the OED's definition of husband in its verb form. As Sylvia Federici (Reference Federici2004) shows, the development of actually existing capitalism in the Anglo-European world depended in large part on husbands’ ownership of their wives and their labour (power). To a 19th-century husband, unfaithfulness and divorce amounted to a status blow and an economic injury, as well as a gendered insult. Mixing themes of husbandry and enterprise, status and property, Dr. Luke's language conflates ownership, masculine honour, paternalism and marriage in ways 19th century courts would have found familiar.

V. Statute of limitations – not just a detail

One of the basic assumptions in US labour law is that ‘employees cannot be full partners in the enterprise because such an arrangement would interfere with inherent and exclusive managerial rights of employers’ (Atleson Reference Atleson1983, p. 9). Dr. Luke's charge of tortious interference failed against David Sonenberg, but not because any of the three men involved (Dr. Luke, Sonenberg, Judge Schweitzer) rejected that assumption. Rather, their shared ‘employer chauvinism’ (Ewing Reference Ewing1977, p. 43) provides a common background against which their differences can be contrasted.

The validity of Dr. Luke's suit against Sonenberg came into question over the interpretation of a time limit on an entrepreneur's ability to sue for tortious interference. In order for Dr. Luke's claims to be validated by the court, the tort – the injury, the damage – had to have occurred no more than three years before he made his claim to the court. The window for action would be closed and his claim would not be viable if more than three years had elapsed since the injury. The court's discussion of this question in this case reflects how non-controversially the Lumley doctrine imposes on workers a duty of loyalty (backed up by the law's readiness to deny access to other opportunities) that is not reciprocally expected of the entrepreneurs who engage them.

Sonenberg had made his agreement with Kesha more than three years before the suit; the statutory time limit on suing him for tortious interference with Dr. Luke's contractual relations with Kesha had passed. Yet Dr. Luke argued that each new bit of work that Kesha undertook for Sonenberg constituted a new violation, a new injury. To Dr. Luke, the injury was recurring and renewing as long as Kesha and Sonenberg continued working together. However, the court disagreed. The court rejected what it called Dr. Luke's ‘mistaken conten[tion] that the statute of limitations [was] reset with every new act’ (DAS Communications, Ltd. v Sebert 2011, p. 10). On the one hand, there appears little question that Dr. Luke could have made a valid charge had the statute of limitations window not closed. On the other hand, what seems most striking in a broader historical context is the court's definition of the injury. The injury here is that first moment of infidelity, when Kesha shifted her loyalty by signing the 2006 contract with DAS. Sonenberg too moved more slowly than Kesha preferred. Even though the singer was ready to get to work in 2006, Sonenberg did not start putting her actively to work until 2007. Nevertheless, the court stated that this year of idleness did not matter. What did matter was Kesha's fatal promise of labour power to Sonenberg – the injury took place the instant her signature conveyed (or purported to convey) to Sonenberg the right to her capacity to labour.

Kesha's original 2005 promise to Dr. Luke gave him an exclusive right to her labour power, no matter when they might actually begin to work together, until either she completes all of the options Dr. Luke exercises or Dr. Luke drops her from his roster. To the court, Dr. Luke's legal susceptibility to injury by a competitor's tortious interference with his contractual relations came into being the day Kesha assigned her labour power to him: 26 September 2005. Similarly, the court perceived that ‘the moment [Kesha] signed with [Sonenberg], she breached the Gottwald agreement’ (DAS Communications, Ltd. v Sebert 2011, p. 7, emphasis added). Kesha ‘was not only promising to act in a manner counter to Mr. Gottwald's interests when she signed with [Sonenberg] – she was acting counter to Mr. Gottwald's interests’ (2011, p. 8, emphasis added). In this light, Kesha's scribal promise to Sonenberg was an act of infidelity to Dr. Luke of no less significance than would have been her recording of an album for Sonenberg. Dr. Luke's suit against Sonenberg for tortious interference was invalid because he sued too late, not because there was no infidelity. Kesha's commodification was not controversial.

Judge Schweitzer's treatment of Kesha's promise to work as conveying an exclusive right to Kesha's labour power (excluding even Kesha's own claims) rehearses what VanderVelde (Reference VanderVelde1992) calls the ‘gendered origins’ of tortious interference (21st century procurement, seduction, enticement). The 1853 decision in the argument between impresarios Benjamin Lumley and Frederick Gye over the singing services of Johanna Wagner established this possibility: a professional's promise to work gave the promisee (in this case Lumley) a right against potential competitors, a right to the suppression of entrepreneurial risk. To reiterate, before Lumley v. Gye, only servants were juridically defined as susceptible to enticement, and only masters of servants could charge competitors with enticement. The employer of a professional lacked the power enjoyed by the master of a servant. Lumley v. Gye dissolved the juridical membrane excluding independently contracting professionals from the law of master and servant and its criminally enforceable obligations, codifying the principle that ‘contractual “rights” are not just rights between the parties but something (or rather some thing) deserving “protection” from interference by others’ (Howarth Reference Howarth2005, p. 222).

VI. Conclusion

In Carole Pateman's (Reference Pateman1988) analysis, the so-called ‘social contract’ that accounts theoretically for the liberal freedom and political equality of modern property-owning men was accompanied by a ‘sexual contract’ that maintained women's subordinate status in the new liberal regime. The sexual contract shows up in the triangular relationship linking Dr. Luke, Kesha and DAS Communications: the two men are juridical subjects, Kesha (as worker, but also as a woman) a juridical object. The argument between Lumley and Gye featured what Swan calls the ‘male–female contract bond’ (Swan Reference Swan2012, p. 184), in which the contractual aspect of the bond – the presupposition of equal status between contracting parties, for example – is overcome conceptually and practically by gender hierarchy. In Swan's words, with the male–female contract bond, the court ‘took a contractual bond, and focused not on the legal significance of that bond, but on its relational significance’ (Swan Reference Swan2012, p. 184, original emphasis). The court set aside Wagner's legal subjectivity, as demonstrated by the capacity to enter into a contract in the first place, and ruled on the basis of gender. Contextual, particularistic (Victorian) gender relations became codified in universalistic law; the court stretched the doctrine of enticement (seduction, procurement, interference) to encompass professionals.

Are workers musicians? According to VanderVelde and Swan, by the time the doctrine came to apply to white professionals in the early 20th century, it had been gender-washed, neutralised. Thus, when the two 21st-century pop producers invoke bonds with the pop singer-songwriter that entitle them to recognition as subjects and require her classification as an asset, they do so not as men but as entrepreneurs; when the judge rules against Dr. Luke on the question of the time limitation, he endorses the producers’ standing as (competing) claimants not because Kesha is a woman, but because she is a productive worker. To my mind, the feminist scholarship answers the question ‘Why did a case involving a professional singer play such a huge role in transforming the legal boundaries and norms of modern contractual relations?’ with the answer ‘Because the singer was a woman’. I endorse this answer and cite this work heavily in order to bring it to the attention of colleagues and students in our field.

It is also clear that class played a role that has not been given much attention in the scholarship on Lumley v. Gye, feminist and otherwise (Macnair Reference Macnair2011 is an exception). This may be as much because popular music scholars, adept at class analysis, have so far overlooked the case as it is attributable to the practical narrowness of much legal scholarship. If the point is to understand independent contractual arrangements between freely contracting, juridically equal buyers and sellers of professional services, then whatever was happening with masters and servants in the worlds of weaving, pottery and leatherwork (for instance) may not appear relevant. However, a ruling class whose unity was unique in Europe was ‘supported by every institution in England after 1688 in their determination to increase productivity and profit’; from the early 18th century, ‘they were to cut wages, control working hours, and abolish working people's ability to organize protests’ (Rosen Reference Rosen1981, p. 26). By the late 1840s, ‘in England as on the Continent, all fractions of the ruling classes’ were united, wrote Marx, ‘under the common slogan of the salvation of property, religion, the family, and society’ (Marx Reference Marx and Fowkes1977, p. 397). Male and entrepreneurial supremacy seem to have made Johanna Wagner stand out as an attractive target. Entrepreneurs engaging professionals to make money, up to and including music producer Dr. Luke, would benefit mightily from Lumley's achievement. In VanderVelde's words, ‘gender served as a catalyst for a rule that subordinated all professional employees to the mastery of their employers’ (VanderVelde Reference VanderVelde1992, p. 836).

The triangular relation of Dr. Luke, David Sonenberg, and Kesha suggests that the misogyny at the heart of the Lumley decision, as well as its class-war context, is as alive as ever in the tort of interference, and that the Lumley doctrine played a significant role in the expansion of entrepreneurial supremacy and still plays one in its maintenance. More work remains to be done in discovering how historical episodes of class and gender war have shaped the social relations of music making, and vice versa.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Olufunmilayo Arewa, Ellis Jones, and Leslie Meier for help clarifying this analysis.