The origins of ideological behavior

One of the most profound insights of Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism (Reference Arendt1951) is the idea that totalitarian ideologies work not simply by coercing the external behavior of citizens—they function by coercing their minds. Arendt noted that ideologies force adherents to surrender their capacity for independent thought and instead impose a compulsive, tyrannical logic on the minds of adherents. While Arendt’s theories have sparked substantial debates in the social and political sciences (e.g., Benhabib, Reference Benhabib2003; Canovan, Reference Canovan1994; Villa, Reference Villa2000), they have been largely overlooked by cognitive science, the empirical science of thought. This disciplinary neglect is notable given the central role of thoughts and thoughtlessness in Arendt’s analyses. It is therefore pertinent to use the tools of modern science to ask: Is there a relationship between ideological worldviews and the fundamental mechanisms of thought and reasoning? And if so, how deeply does the effect of ideologies penetrate into our cognitive processes?

The proposal detailed here argues that there is an underlying relationship between high-level ideologies and low-level perception and cognition that may be deeper and more complex than Arendt envisioned. It posits that individuals’ private ideologies are manifestations of their perceptual and cognitive tendencies, influenced by chronic and temporary experiences. Furthermore, it suggests that strong engagement with forceful ideologies can subsequently shape perceptual and cognitive functioning. Importantly, perception and cognition here are operationalized in terms of the neuropsychological literature—that is, in terms of the way in which brains process and evaluate stimuli. It is therefore a fundamentally neurocognitive framework of ideologies, exploring how our understanding of the brain can illuminate questions such as: How are ideologies internalized by the minds of adherents? What factors increase or decrease an individual’s susceptibility to ideological thinking? Does strong engagement with an ideology shape the individual’s cognitive and neural functioning?

The neurocognitive model of ideological behavior

A neurocognitive approach to the study of ideology begins from the premise that we can study ideologies in terms of their form and structure, and not purely in terms of the content of their beliefs (Zmigrod, Reference Zmigrod2020a). Hence, we can study what it means to be ideologically extreme and dogmatic without necessarily highlighting whether that belief system is left- versus right-wing, nationalistic versus globalist, or religious versus atheist. Actions and thoughts are ideological insofar as they reflect a rigid adherence to a doctrine, resistance to evidence-based belief updating, and a selective orientation in favor of fellow adherents (the in-group) and antagonistic toward non-adherents (the out-group) (Zmigrod, Reference Zmigrod2020a, Reference Zmigrod2020b). Ideological thinking is epistemically dogmatic and interpersonally intolerant. Ideological extremism, from this perspective, is therefore a state in which individuals are dogmatic and intolerant to an extent that can facilitate a willingness to harm those who do not follow the ideology’s premises, and at times even to incur personal costs for the sake of the ideology. It is possible to envision a spectrum on which some individuals are non-ideological, if they are receptive to evidence and exhibit tolerance toward dissimilar others, while others may be ideological or ideologically extreme, depending on the intensity of their dogmatic rigidity and hostility toward out-groups.Footnote 1

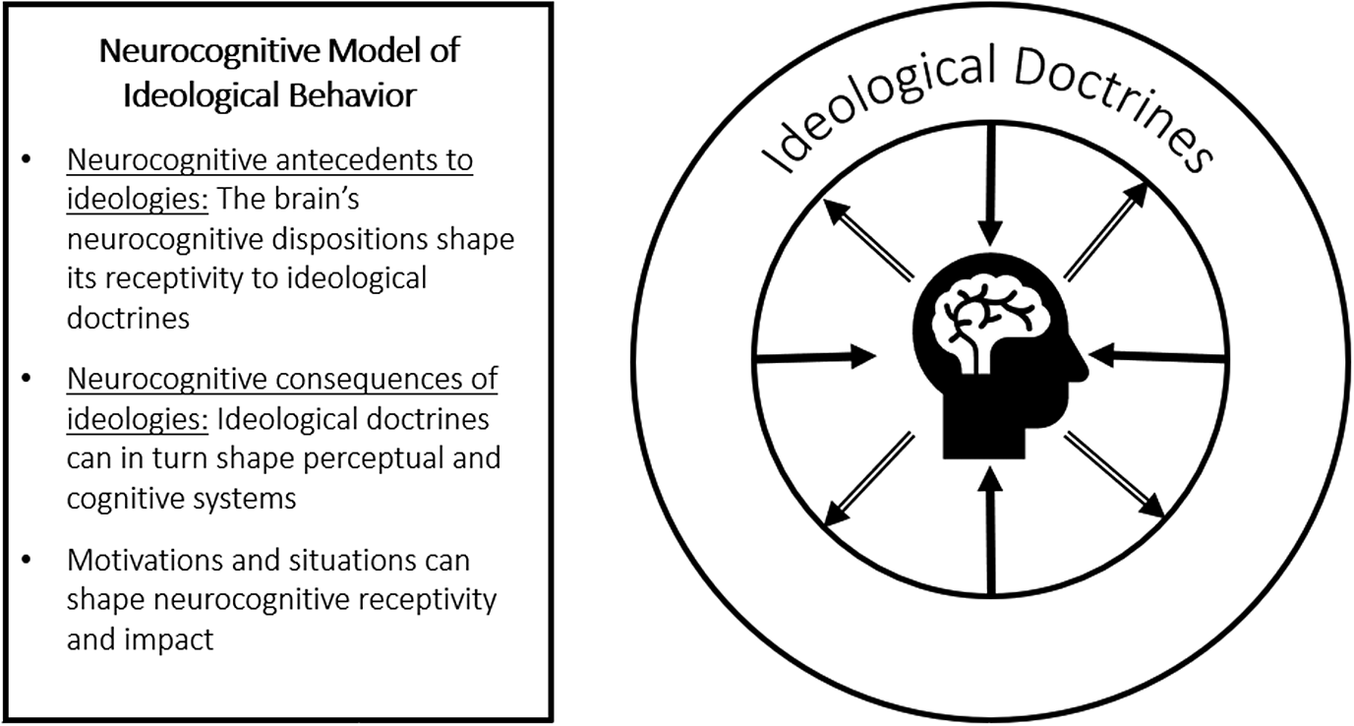

The neurocognitive model makes two essential claims. First, it argues that there are neurocognitive antecedents to ideological thinking: the brain’s neurocognitive dispositions shape its receptivity to ideological doctrines. Second, there can be neurocognitive consequences to ideological engagement: exposure and adherence to ideological doctrines can shape perceptual and cognitive systems (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Outline of the neurocognitive model of ideological behavior.

What are neurocognitive antecedents of ideological thinking? These are neurobiologically grounded perceptual and cognitive dispositions that heighten the allure of ideological groups, doctrines, and arguments. The notion of neurocognitive antecedents builds on the fundamental insight that has emerged among cognitive scientists over the past 50 years that individuals vary in the way in which their brains process information from the environment. When presented with identical stimuli, individuals will process and physiologically react to these stimuli in different ways, based on their cognitive and neural architecture (Posner & Rothbart, Reference Posner and Rothbart2018; Sallis et al., Reference Sallis, Smith and Munafo2018; Trofimova, Reference Trofimova and Arnold2016; Trofimova & Robbins, Reference Trofimova and Robbins2016; Uher, Reference Uher2018). Thus, there are neurocognitive dispositions—enduring, biologically based dispositional tendencies in processing, evaluating, and responding to stimuli—that guide individuals’ behavior and decision-making. These neurocognitive dispositions are stable over time and typically not under explicit conscious control (Trofimova et al., Reference Trofimova, Robbins, Sulis and Uher2018).

However, theories of the emergence and maintenance of ideological worldviews have not traditionally incorporated the idea of neurocognitive dispositions. Consequently, the study of ideology is now ripe for a “neurocognitive model” that emphasizes how cognitive, perceptual, and neurobiological dispositions can increase or reduce an individual’s susceptibility to ideological worldviews. The neurocognitive model posits that individuals’ neurobiologically grounded implicit tendencies can make them more receptive or resistant to ideological systems. It is rooted in the idea that information-processing strategies evident in ideologically neutral contexts will also seep into the strategies used to process ideological arguments; hence, we can begin to characterize the properties of the “ideological brain.”

The idea that there are individual differences that confer susceptibility or resistance to ideological doctrines is not new. Nonetheless, past research has avoided making the strong claim that these individual differences have a biological and neurocognitive character. It is possible to observe that individuals differ in their susceptibility to ideological processes in the theories and experiments of the early days of social psychology. In the classic social psychological paradigms of social conformity and obedience to authority of the mid-twentieth century by Asch (Reference Asch1956), Milgram (Reference Milgram1963, Reference Milgram1974), Festinger (Reference Festinger1950, Reference Festinger and Jones1954), and others, there was always a percentage of participants who resisted conformity or obedience (even in studies with small participant samples; see Blass, Reference Blass1991; Haslam & Reicher, Reference Haslam and Reicher2017; Martin & Hewstone, Reference Martin, Hewstone, Hogg and Tindale2001). The percentage of resisting participants oscillated between 10% and 30% according to the specific experimental paradigm, but overall, some participants always rebelled—there were consistent outliers to universal authoritarian tendencies. This mirrored the historical reality that in contexts of conflict, war, and genocide, (1) some individuals are more resistant to ideological systems that promote dogmatism and out-group hostility, and (2) some individuals tend to display greater receptivity to ideological systems (Zmigrod, Reference Zmigrod2020a).

Indeed, social scientists have frequently noted that not all individuals are equally likely to internalize ideologies and adhere to them in an extreme fashion. In their pioneering book The Authoritarian Personality, Theodor Adorno and colleagues (Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1950) asked “why is it that certain individuals accept [fascist] ideas while others do not?” (p. 3). Soon afterward, in Reference Crutchfield1955, psychologist Richard Crutchfield posed a similar question about conformity: “what traits of character distinguish between those [people] exhibiting much conformity behavior … and those exhibiting little conformity?” (p. 194). Building on these ideas, the sociologist Edward Shils (Reference Shils1958) noted that individuals are differentially susceptible to ideological doctrines, and this is not purely a matter of upbringing or socioeconomic context: “not all those who live in a broken and disadvantaged condition are drawn equally by the magnet of the ideological orientation” (pp. 463–464). Social psychologist Thomas Blass (Reference Blass1991) further highlighted the presence of interpersonal variation in ideological and authoritarian processes: “that there are individual differences in obedience is a fact because in most obedience studies, given the same stimulus situation, one finds both obedience and disobedience taking place” (p. 402). The recognition that there is variability in tendencies to conform, obey, and adhere to ideological dogmas is therefore at least 70 years in the making—but here it is proposed that we can shed light on these individual differences by adopting a neurocognitive model of ideological behavior.

As noted earlier, the neurocognitive model also makes a second claim: it argues that there are neurocognitive consequences to ideological engagement. That is, deep attachment and adherence to ideological doctrines and groups can have an impact on the brain. This claim originates from the well-established notion that the brain easily forms habits when exposed to particular experiences and reinforcement environments (e.g., Caspi & Moffitt, Reference Caspi and Moffitt2006; Leong et al., Reference Leong, Radulescu, Daniel, DeWoskin and Niv2017; Robbins & Costa, Reference Robbins and Costa2017). The concept of brain plasticity reflects the rich neuroscientific understanding that experience can fundamentally change the structure and function of cerebral neurons, and so the brain is highly responsive to the properties of its environment (Lewkowicz & Ghazanfar, Reference Lewkowicz and Ghazanfar2009; McEwen, Reference McEwen2012; Sale et al., Reference Sale, Berardi and Maffei2014).

We can consider dogmatic ideological contexts—which espouse a rigid doctrine, resistance to evidence-based belief updating, and strict boundaries between social groups (Zmigrod, Reference Zmigrod2020a)—as such neurocognitively influential environments. Repeated exposure to dogmatic and parochial ideological contexts is therefore likely to shape general, non-ideological information-processing strategies. In the same way that harsh parental and socioeconomic environments can alter genetic expression (Borghol et al., Reference Borghol, Suderman, McArdle, Racine, Hallett, Pembrey and Szyf2012; Essex et al., Reference Essex, Thomas Boyce, Hertzman, Lam, Armstrong, Neumann and Kobor2013), cognition (Everson-Rose et al., Reference Everson-Rose, Mendes de Leon, Bienias, Wilson and Evans2003; Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, Turrell, Lynch, Everson, Helkala and Salonen2001), physiology (Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Karlamangla, Gruenewald, Koretz and Seeman2015; Gruenwald et al., Reference Gruenewald, Karlamangla, Hu, Stein-Merkin, Crandall, Koretz and Seeman2012; Hagan et al., Reference Hagan, Roubinov, Adler, Boyce and Bush2016), and even physical health (Springer et al., Reference Springer, Sheridan, Kuo and Carnes2007; Wickrama et al., Reference Wickrama, Conger and Abraham2005), ideologies can impact the way in which the mind processes information and perceives stimuli. As noted in the social cognition literature, “the structure of the shared external environment shapes neural responses and behaviour” (Hasson et al., Reference Hasson, Ghazanfar, Galantucci, Garrod and Keysers2012, p. 120). Compelling collective ideologies often impose a powerful structure on the social and personal environment (Zmigrod, Reference Zmigrod2020a), and so their devout adoption can have substantial downstream effects on the brain. This extends the claims made by political philosophers such as Arendt into new territory: ideologies can have a profound impact on the minds of adherents by shaping their neural and cognitive functioning.

The roles of situations and motivations

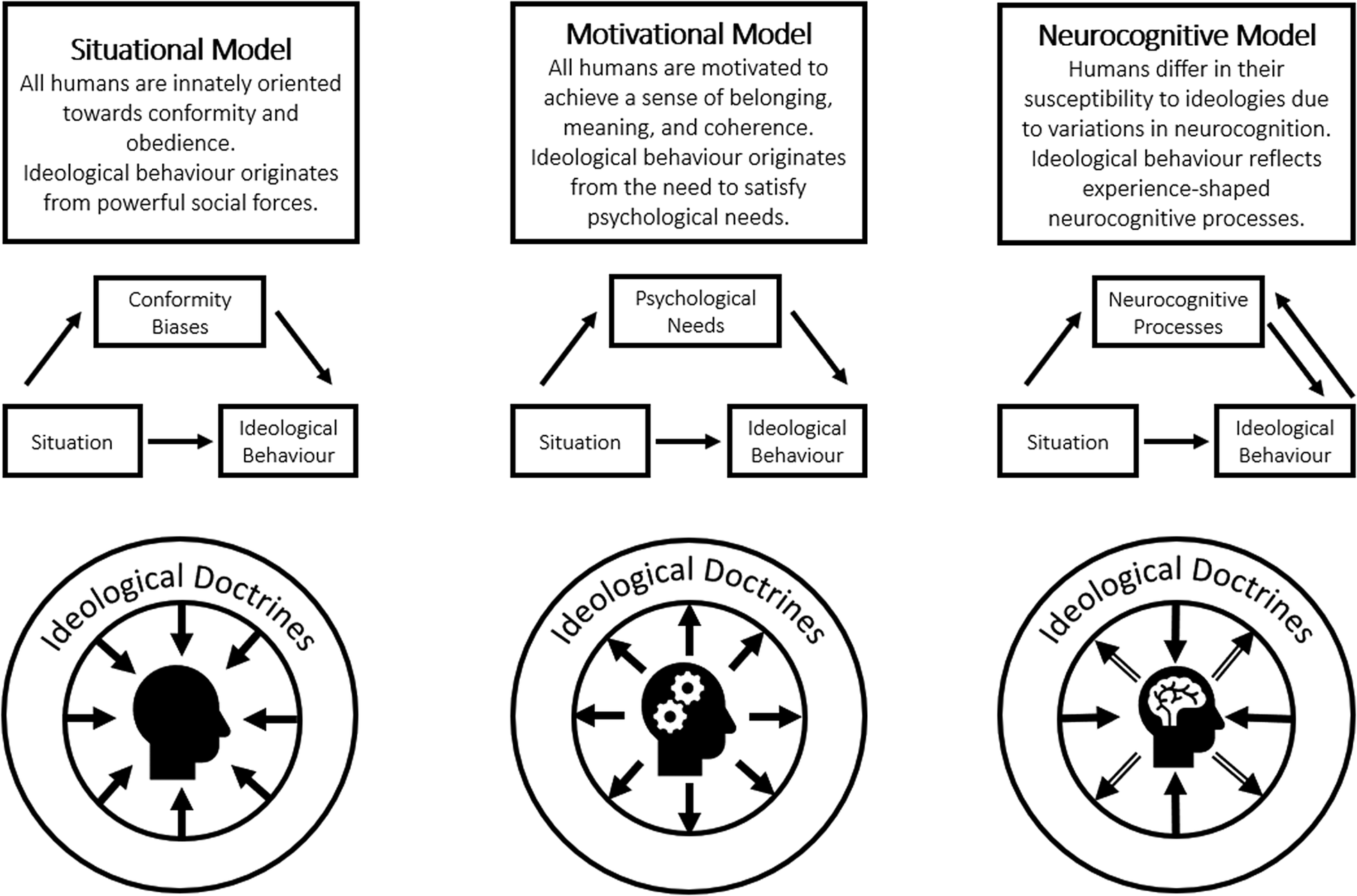

The neurocognitive model of ideological behavior proposed here builds upon—but departs markedly from—two dominant schools of thought that have historically characterized the study of ideologically motivated action (see Figure 2). The first, which we can call the “situational” model, posits that under certain conditions, anybody would commit atrocities in the name of an ideological group or cause. That is, sufficiently forceful social situations will spur humans to conform and obey authority and, in turn, numb their capacities for independent reasoning and judgment. The situational model proposes that sufficiently forceful situations will homogenize differences between individuals and produce authoritarian, dogmatic, and self-sacrificial collectives (see Figure 2A). This model gained prominence in the shadow of the totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century and helped alleviate concerns that particular historical groups have an innate capacity for evil. It places universal human biases at its core and leaves little room for individual differences in receptivity to ideological systems. It is also consistent with models in political science that emphasize the strong role of environmental socialization on the formation of political orientations (e.g., Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Hyman, Reference Hyman1959; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992).

Figure 2. Summaries of the premises, assumptions, and essential causal relations posited by the (A) situational model, (B) motivational model, and (C) neurocognitive model of ideological behavior. Each model gives a different weight to the role of the mind and brain in shaping ideological attitudes (increasing from left to right), and each model makes different assumptions about how external situations shape ideological behavior.

The second account can be summarized as the “motivational” model, which espouses that dogmatic and parochial ideological behavior is the result of the activation of relational, existential, or epistemic motivations. The motivational model was influenced by psychoanalytic traditions that considered belief and behavior as fundamentally sculpted by unconscious needs and desires. It therefore suggests that “ideological belief systems reflect motivational concerns” (Jost et al., Reference Jost, Nosek and Gosling2008, p. 134), such as the need to belong, to attain meaning, and to possess a coherent explanation of the world (see Figure 2B). In accordance with Freudian and psychoanalytic thought, Adorno and colleagues (Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1950) set the tone for the field by discussing susceptibility to ideologies in terms of needs and motivations: “ideologies have for different individuals, different degrees of appeal, a matter that depends upon the individual’s needs and the degree to which these needs are being satisfied or frustrated” (p. 2). The language of needs and motivations has persisted as the primary lens through which ideological processes are discussed in the academic literature. This has had a powerful effect on how the psychological roots of ideologies have been conceptualized, operationalized, and measured: prevailing theories of the psychology of various ideologies and associated processes, such as conservatism (Jost et al., Reference Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski and Sulloway2003), religious fundamentalism (Hill & Williamson, Reference Hill and Williamson2005), authoritarianism (Adorno et al., Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1950), system justification (Jost & Banaji, Reference Jost and Banaji1994), and violent radicalization (Kruglanski et al., Reference Kruglanski, Gelfand, Bélanger, Sheveland, Hetiarachchi and Gunaratna2014), have been explicitly motivational accounts. Nevertheless, the robust cognitive scientific understanding that human behavior is not solely determined by needs and motivations suggests that purely motivational accounts of the emergence and maintenance of ideological worldviews may be insufficient.

In contrast with the situational and motivational accounts, the neurocognitive model argues that ideological worldviews reflect cognitive and perceptual tendencies, and, in turn, ideologies can influence low-level neurocognitive processes (Figure 2C). It therefore considers ideological thinking as neurocognitively negotiated, rather than the product of authoritarian situations or psychological needs. Nonetheless, the neurocognitive model still makes room for the effect of situations and motivations. Situations that elicit stress or strong social pressure can amplify neurocognitive processes (e.g., Lupien et al., Reference Lupien, Maheu, Tu, Fiocco and Schramek2007; Schoofs et al., Reference Schoofs, Preuß and Wolf2008) that guide individuals—to different degrees—to behave in ideological ways. For example, a stressful situation can impair cognitive flexibility and executive function (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Hillier, Smith, Tivarus and Beversdorf2007; Plessow et al., Reference Plessow, Fischer, Kirschbaum and Goschke2011; Schoofs et al., Reference Schoofs, Preuß and Wolf2008) and thereby produce ideologically rigid behavior and make the individual receptive to propaganda. Similarly, the activation of motivations such as epistemic needs to attain coherence can shape information processing and working memory in motivation-consistent directions (Lassiter et al., Reference Lassiter, Briggs and Slaw1991; Locke, Reference Locke2000; Verplanken, Reference Verplanken1993). For instance, epistemic motivations for coherence can influence the perceptual interpretation of data (den Ouden et al., Reference den Ouden, Kok and De Lange2012 Dijksterhuis et al., Reference Dijksterhuis, Van Knippenberg, Kruglanski and Schaper1996), or existential motivations to attain meaning can make attentional processes attuned to meaning-producing information (Pessoa, Reference Pessoa2009; Pessoa & Engelmann, Reference Pessoa and Engelmann2010; Thórisdóttir & Jost, Reference Thórisdóttir and Jost2011). Careful attention to cognitive mechanisms can also shine a light on phenomena such as the uncertainty paradox (Haas & Cunningham, Reference Haas and Cunningham2014), whereby threat modulates the extent to which uncertainty breeds tolerance or intolerance: when conditions are safe, uncertainty can elicit an exploratory stance that facilitates political tolerance, whereas when conditions are threatening, uncertainty can lead to closed-mindedness. Incorporating physiological frameworks for how threat shapes cognition can help provide a more biologically grounded explanation for these context-dependent effects.

The neurocognitive model can also inform work on the genetic heritability of ideological beliefs (Hatemi et al., Reference Hatemi, McDermott, Eaves, Kendler and Neale2013; Hatemi et al., Reference Hatemi, Medland, Klemmensen, Oskarsson, Littvay, Dawes, Verhulst, McDermott, Nørgaard, Klofstad, Christensen, Johannesson, Magnusson, Eaves and Martin2014; Israel et al., Reference Israel, Hasenfratz and Knafo-Noam2015) by positing specific mechanisms through which genetic variations contribute to neurocognitive differences and thus ideological attitudes. It thus is able to posit mechanistic theories about how biological processes shape ideological worldviews. Moreover, the situational and motivational models assume unilateral effects: the situational model views situations as imposing themselves on the individual (Figure 2A), and the motivational model sees the individual’s needs as stimulating the expression of ideological thought (Figure 2B). In contrast, the neurocognitive model explicitly postulates that there are bidirectional processes between the ideological environment and the brain (Figure 2C).

Empirical support for the neurocognitive model

Evidence for the neurocognitive antecedents and consequences of ideologies can be found in the burgeoning fields of political neuroscience and experimental social psychology. Recent work has revealed that ideologically neutral cognitive and perceptual decision-making processes are related to higher-level ideological convictions and beliefs (Rollwage et al., Reference Rollwage, Dolan and Fleming2018; Rollwage et al., Reference Rollwage, Zmigrod, de-Wit, Dolan and Fleming2019; Zmigrod et al., Reference Zmigrod, Rentfrow and Robbins2018; Zmigrod, Rentfrow, & Robbins Reference Zmigrod, Rentfrow and Robbins2019; Zmigrod, Rentfrow, Zmigrod, & Robbins Reference Zmigrod, Rentfrow, Zmigrod and Robbins2019; Zmigrod, Zmigrod, Rentfrow, & Robbins Reference Zmigrod, Zmigrod, Rentfrow and Robbins2019; Zmigrod, Reference Zmigrod2020b). Three cognitive traits that have been recently shown to confer susceptibility to ideological thinking are particularly noteworthy: (1) cognitive inflexibility, (2) impaired metacognitive awareness, and (3) slower perceptual evidence accumulation processing. First, there is evidence that a tendency toward mental rigidity can foster ideological rigidity. Cognitive inflexibility—operationalized as a difficulty with switching between modes of thinking and adapting to changing environmental contingencies—has been implicated in extreme ideological identities (for a review, see Zmigrod, Reference Zmigrod2020b) in the context of politics (Zmigrod et al., Reference Zmigrod, Rentfrow and Robbins2020), nationalism (Zmigrod, Rentfrow & Robbins, Reference Zmigrod, Rentfrow and Robbins2018), religion (Zmigrod, Rentfrow, Zmigrod, & Robbins, Reference Zmigrod, Rentfrow, Zmigrod and Robbins2019), dogmatism (Zmigrod, Zmigrod, Rentfrow, & Robbins, Reference Zmigrod, Zmigrod, Rentfrow and Robbins2019), and a willingness to endorse violence and self-sacrifice (Zmigrod, Rentfrow, & Robbins, 2019b). In these studies, cognitive inflexibility was measured with objective behavioral tests of executive function and perception, and so the findings are not susceptible to the problems of self-report personality surveys, in which there can be biases of social-desirability, self-perception, and social norms. The rigidity with which individuals perceive and process stimuli generally was thus linked to the rigidity of their ideological beliefs. Hence, these findings demonstrate that dispositions in implicit information-processing tendencies may be tied to high-level explicit ideological worldviews.

Second, recent cognitive research has illustrated a relationship between impaired metacognition—the awareness of one’s cognitive processes—and ideological dogmatism on both the political left and right (Rollwage et al., Reference Rollwage, Dolan and Fleming2018). Here, too, the researchers employed neuropsychological paradigms and computational models to reveal differences between individuals who were ideologically moderate versus extreme. Individuals who were ideologically extreme were characterized by impaired metacognition, suggesting that individuals’ capacity to be aware of and to regulate their cognitive functioning may confer susceptibility to internalizing ideologies. There is growing empirical support for the idea that resistance to evidence in the sociopolitical sphere may therefore emerge from a neurocognitive impairment in metacognitive processes (Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Amelung and Said2019; Heyes et al., Reference Heyes, Bang, Shea, Frith and Fleming2020; Kleitman et al., Reference Kleitman, Hui and Jiang2019; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Savani and Fincher2019; Rollwage et al., Reference Rollwage, Zmigrod, de-Wit, Dolan and Fleming2019; Sinclair et al., Reference Sinclair, Stanley and Seli2019).

Another example of the neurocognitive correlates of ideological worldviews lies in the study of perceptual processes. Recent research examining the cognitive signatures of a range of ideological attitudes found that impairments in strategic information processing were linked to more authoritarian, conservative, nationalistic, and religious tendencies (Zmigrod et al., Reference Zmigrod, Eisenberg, Bissett, Robbins and Poldrack2021). This was manifest in implicit behavioral paradigms that measure performance on executive functioning tasks associated with working memory and planning. The findings could indicate that difficulty in planning and executing complex action sequences in basic perception increases people’s reliance on coherent collective dogmas that simplify the world into absolute explanations and clear behavioral prescriptions. Furthermore, the study revealed that slower evidence accumulation of perceptual data (on the order of milliseconds) predicts a dogmatic thinking style (Zmigrod et al., Reference Zmigrod, Eisenberg, Bissett, Robbins and Poldrack2021). This analysis tapped into low-level neurocognitive processes by relying on drift-diffusion modeling of trial-by-trial performance on two-forced choice tasks. Notably, dogmatic individuals also exhibited tendencies toward impulsivity, suggesting that dogmatism may arise out of a cognitive style characterized by premature decisions based on imperfectly processed evidence. Dogmatism in evaluating evidence could therefore reflect the individual’s impairments in processing perceptual evidence. Moreover, the analysis suggested that response caution—defined as the trade-off between accuracy and speed (with a preference for accuracy, in tasks where both speed and accuracy are rewarded)—was related to more socially conservative and nationalistic worldviews. Cautious perceptual strategies may therefore percolate to cautious (i.e., conservative) ideological beliefs. Studying the relationship between ideological attitudes and individual differences in low-level perceptual and cognitive processing can therefore help illuminate the character of the ideological brain.

Importantly, the cognitive traits that confer susceptibility to thinking ideologically manifest in simple neuropsychological and perceptual tasks which are ideologically neutral and occur on time scales that are much faster (in the order of milliseconds) than those during which ideological attitudes are formed. This is suggestive of domain-general and time-invariant processes and strategies that operate on multiple time scales and across a variety of contexts.

This idea is commensurate with, and supported by, extant research in biopolitics indicating physiological differences between political liberals and conservatives (e.g., Ahn et al., Reference Ahn, Kishida, Gu, Lohrenz, Harvey, Alford, Smith, Yaffe, Dayan and Montague2014; Arceneaux et al., Reference Arceneaux, Dunaway and Soroka2018; Friesen et al., Reference Friesen, Gruszczynski, Smith and Alford2020; Hibbing, Smith, & Alford, Reference Hibbing, Smith and Alford2014; Hibbing, Smith, Peterson, & Feher, Reference Hibbing, Smith, Peterson and Feher2014; for a recent review, see Smith & Warren, Reference Smith and Warren2020). The guiding theoretical assumption behind much of the psychophysiological and neuroscientific research on political orientation is that certain kinds of implicit, automatic emotional reactivities—which can be evident across multiple timescales and in diverse stimulus domains—underpin individuals’ political tendencies. The neurocognitive model of ideological thinking can assimilate these findings and perhaps offer a framework through which to ask about the potential bidirectional relationship between physiological traits and ideological immersion. What baseline individual differences—coded by genetic markers—contribute to susceptibility to ideological thinking? And how do strong ideological environments shape an individuals’ physiological reactivity? Addressing the potential bidirectionality of these effects over time, as well as the need to study ideological thinking, dogmatism, and extremism beyond purely the classic left/right political divide, is essential to understand these ideological and neurocognitive phenomena in an ecologically valid way. Appreciating, and conceptually separating, the antecedents and consequences of ideological behavior on the mind may be a critical avenue forward that could help resolve some empirical inconsistencies (Smith & Warren, Reference Smith and Warren2020) in the political psychophysiology field. This will also be supported by drawing on research from adjacent disciplines which highlights humans’ capacity for neuroplasticity and the fact that neurocognition can be fundamentally shaped by environments (Blix et al., Reference Blix, Perski and Savic2013; Boyke et al., Reference Boyke, Driemeyer, Gaser, Buchel and May2008; Creswell et al., Reference Creswell, Taren, Lindsay, Greco, Gianaros, Fairgrieve, Marsland, Brown, Way, Rosen and Ferris2016; Draganski et al., Reference Draganski, Gaser, Busch, Schuierer, Bogdahn and May2004; Hölzel et al., Reference Hölzel, Carmody, Evans, Hoge, Dusek, Morgan, Pitman and Lazar2009; Maguire et al., Reference Maguire, Gadian, Johnsrude, Good, Ashburner, Rackowiak and Frith2000)—and so ideological environments also need to be taken seriously as such cognitively influential environments.Footnote 2

Indeed, research from the cognitive science of religion (Barrett, Reference Barrett2000; Bering, Reference Bering2006; Norenzayan & Shariff, Reference Norenzayan and Shariff2008; Sosis & Alcorta, Reference Sosis and Alcorta2003) has illustrated the neurocognitive consequences of ideological engagement. Religion is a useful ideological candidate because of the intensity of its rituals and the variability in religious practices. This line of work has demonstrated that repetitive adherence to religious practices appears to shape visual perception, neurophysiology, and meta-control cognitive policies. For instance, hierarchical visual perception of atheists has been shown to differ from that of neo-Calvinists (Colzato et al., Reference Colzato, van den Wildenberg and Hommel2008; Colzato, van Beest, et al., Reference Colzato, van Beest, van den Wildenberg, Scorolli, Dorchin, Meiran, Borghi and Hommel2010), Italian Roman Catholics (Colzato, van Beest, Reference Colzato, van Beest, van den Wildenberg, Scorolli, Dorchin, Meiran, Borghi and Hommel2010), Orthodox Jews (Colzato, van Beest, Reference Colzato, van Beest, van den Wildenberg, Scorolli, Dorchin, Meiran, Borghi and Hommel2010a), and Taiwanese Zen Buddhists (Colzato, Hommel, et al, Reference Colzato, Hommel, van den Wildenberg and Hsieh2010). There are subtle differences in the visual attentional styles of these different religious groups that parallel the doctrine they espouse, suggesting that religious adherence can fundamentally shape visual attention (Hommel & Colzato, Reference Hommel and Colzato2010, Reference Hommel and Colzato2017). This faith-specific modulation of cognition has also been extended to other types of cognitive and attentional processes, such as temporal discounting (Paglieri et al., Reference Paglieri, Borghi, Colzato, Hommel and Scorolli2013), conflict detection (Pennycook et al., Reference Pennycook, Cheyne, Barr, Koehler and Fugelsang2014), and action control (Hommel et al., Reference Hommel, Colzato, Scorolli, Borghi and van den Wildenberg2011). Anxious attachment styles have also been linked to conspiratorial beliefs, highlighting the plausible relationship between internal working models of the unpredictability of the world that emerge from early childhood experiences and later conspiratorial ideation (Green & Douglas, Reference Green and Douglas2018). These findings are correlational and so longitudinal research is necessary to clearly delineate the causal arrows. Notably, in the domain of cognitive flexibility, Zmigrod, Rentfrow, Zmigrod, and Robbins (Reference Zmigrod, Rentfrow, Zmigrod and Robbins2019) examined participants who had a religious upbringing and those who did not and compared individuals who had “entered” or “exited” religion as well as those who had remained atheistic or religious with respect to their upbringing. Although current religious affiliation was a stronger predictor of cognitive rigidity than past upbringing, a trend did emerge such that nonreligious participants who had a religious upbringing (those who “left” religious ideologies for atheism) were the most cognitively flexible (Zmigrod, Rentfrow, Zmigrod, & Robbins, Reference Zmigrod, Rentfrow, Zmigrod and Robbins2019). The decision to move away from a powerful ideological environment can therefore require substantial cognitive flexibility and effort. Additional research with a longitudinal or temporal dimension will allow for clearer dissection of the causal arrows in such cases, possibly by accounting for the intensity or devoutness of the ideological environment, which is not equivalent across all individuals who grow up in religious contexts.

Furthermore, neuroscientists have posited that religion may serve as a neural antidote to anxiety and uncertainty (Inzlicht et al., Reference Inzlicht, Tullett and Good2011). Correspondingly, it has been shown that invoking religious concepts can alter the neurophysiological error-monitoring of religious participants. Specifically, amongst religious believers, contemplating religious thoughts (such as God’s love) can dampen error-related negativity, a neural signal that emerges from the anterior cingulate cortex that is implicated in monitoring performance and affective response to errors (Good et al., Reference Good, Inzlicht and Larson2015). Moreover, greater religious zeal—a fanatic form of belief—was associated with lower error-related negativity when completing a perceptual Stroop task (Inzlicht et al., Reference Inzlicht, McGregor, Hirsh and Nash2009), corroborating the idea that religion can act as an anxiety-reducing palliative because of its general epistemic and meaning-creating properties (Inzlicht et al., Reference Inzlicht, Tullett and Good2011). It is important to qualify these findings and address the potential bidirectionality of these effects; religious exposure can shape individuals’ neurocognition and, at the same time, neurocognitive predispositions can influence the type and level of zeal with which individuals adhere to the religious ideology. Consequently, while religion offers a valuable test case for the impact of ideologies on the brain, processes of ideological self-selection must be considered as well.

Research on conspiracy theories has also productively examined how perceptual and cognitive processes can give rise to conspiratorial or supernatural beliefs (Douglas & Sutton, Reference Douglas and Sutton2018). Examining the relationship between illusory pattern perception and conspiratorial beliefs, van Prooijen and colleagues (Reference van Prooijen, Douglas and De Inocencio2018) found that seeing patterns in chaotic visual stimuli is related to more irrational beliefs. In addition, following a manipulation that strengthened belief in a conspiracy theory, participants perceived world events as though they were more strongly causally connected. It is therefore possible to trace a relationship between pattern perception—even in the domain of vision—and how that relates to adoption of ideological orientations that reflect dogmatic, evidence-resistant (or evidence-distorting) ways of thinking about the world. Conspiracy theories frequently emerge in new, mutating forms, and so can be sufficiently malleable for intervention studies that either challenge or confirm conspiratorial ideation, or that alter the psychological state of the participant (Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Landau and Rothschild2010; van Prooijen & Acker, Reference van Prooijen and Acker2015), allowing researchers to identify the cognitive and perceptual consequences of such ideological exposure.

A similar strand of research that focuses on general personal ideals and values (McGregor et al., Reference McGregor, Zanna, Holmes and Spencer2001; McGregor et al., Reference McGregor, Nash, Mann and Phills2010) rather than specific political or religious ideologies has shown that when individuals are asked to consider how their ideals generate personal conflicts (versus just thinking about the subjective importance of these ideals), they perform more poorly on cognitive tasks requiring self-regulation (Alquist et al., Reference Alquist, Baumeister, McGregor, Core, Benjamin and Tice2018). It is therefore essential to acknowledge the bidirectional links between situations that promote ideological thinking and cognitive processes such as self-control, emotion regulation, and error-prone behavior.

Indeed, neuroscientific research on religion (Inzlicht et al., Reference Inzlicht, Tullett and Good2011; van Elk & Aleman, Reference van Elk and Aleman2017), politics (Haas et al., Reference Haas, Warren and Lauf2020; Jost et al., Reference Jost, Nam, Amodio and Van Bavel2014), and social identities (Decety et al., Reference Decety, Pape and Workman2018; Molenberghs & Louis, Reference Molenberghs and Louis2018) has begun to elucidate the neural correlates of ideological engagement, adherence, and experience. This research has taken the form of lesion studies of traumatic brain injury patients—illustrating that selective lesions to certain brain regions can elevate the experience of religious fundamentalism and mystical experiences (Cristofori et al., Reference Cristofori, Bulbulia, Shaver, Wilson, Krueger and Grafman2016; Zhong et al., Reference Zhong, Cristofori, Bulbulia, Krueger and Grafman2017). There are also structural neuroimaging studies demonstrating that brain regions such as the bilateral amygdala (Nam et al., Reference Nam, Jost, Kaggen, Campbell-Meiklejohn and Van Bavel2018) and the anterior cingulate cortex (Kanai et al., Reference Kanai, Feilden, Firth and Rees2011) may have structurally different forms in people with different ideological worldviews. Functional neuroimaging studies with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalogram (EEG) are also revealing the impact of political ideology (Haas et al., Reference Haas, Baker and Gonzalez2017; Schreiber et al., Reference Schreiber, Fonzo, Simmons, Dawes, Flagan, Fowler and Paulus2013), intergroup threat (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Krosch and Cikara2016; Hein et al., Reference Hein, Engelmann and Tobler2018; Richins et al., Reference Richins, Barreto, Karl and Lawrence2019), social power (Schmid et al., 2017), and race (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Camp, Gomez, Natu, Grill-Spector and Eberhardt2019; Krosch & Amodio, Reference Krosch and Amodio2019) on neurocognitive processes and sensory perception. In a notable study by Schreiber and colleagues (Reference Schreiber, Fonzo, Simmons, Dawes, Flagan, Fowler and Paulus2013), participants completed a risk-taking task while in the brain scanner. Although liberals and conservatives exhibited similar performance on the task, there were differences in the brain activation during the task, suggesting that neuroscientific methods can illuminate unobservable differences in the employment of cognitive processes.

Future directions

It will be essential for a mature neurocognitive model of ideological behavior to address the neurocognitive impacts of both holding certain ideological beliefs (Connors & Halligan, Reference Connors and Halligan2015) and holding any belief to an extreme degree (Rollwage et al., Reference Rollwage, Zmigrod, de-Wit, Dolan and Fleming2019; Zmigrod, Reference Zmigrod2020b; Zmigrod & Goldenberg, Reference Zmigrod and Goldenberg2021). Furthermore, as outlined in Figure 2C, the neurocognitive model explicitly postulates that there are bidirectional links between ideologies and neurocognitive processes, and so future research will need to untangle the causal arrows and cyclical effects between ideological and cognitive phenomena. This echoes the so-called chicken-and-egg problem in political neuroscience, which highlights the difficulty of understanding whether political or psychological processes precede each other (Jost et al., Reference Jost, Nam, Amodio and Van Bavel2014)—and when they compound each other.

Methodologically, the most rigorous paradigm for disentangling the “neurocognition → ideology” equation versus the “ideology → neurocognition” equation are longitudinal experimental designs. Longitudinal and panel designs facilitate the evaluation of how baseline neurocognitive functions predict ideological attitudes over time and whether adopting these ideological attitudes to a strong and passionate degree affects the brain. Sensitivity to measurement methods will be critical here—simply asking people about their support for or antagonism to welfare benefits, for example, is unlikely to yield significant (or interesting) findings, but measuring the intensity of their partisan identities (e.g., Zmigrod, Rentfrow, & Robbins, Reference Zmigrod, Rentfrow and Robbins2020) or the extent to which they would be willing to endorse violence or self-sacrifice for a cause (e.g., Zmigrod, Zmigrod, Rentfrow, & Robbins Reference Zmigrod, Zmigrod, Rentfrow and Robbins2019) would be more potent and psychologically meaningful measures.

Where longitudinal designs are not feasible, it is important to isolate what is theoretically expected to be a stable baseline psychological trait (at least within the time span of an experimental session)—which should be resistant to manipulations—and what is potentially variable and amenable to manipulations. Goudarzi and colleagues (Reference Goudarzi, Pliskin, Jost and Knowles2020) offered a clever experimental paradigm that exemplifies a thoughtful distinction between stable traits and manipulable psychophysiological processes by evaluating how individual differences in ideological support for economic system justification determine the affect and autonomic arousal individuals experience when witnessing videos of inequality. This highlights how ideology impacts neurocognitive processes (tapping into the “ideology → neurocognition” equation); but, at the same time, given that this was not an experimental study requiring manipulation, alternative causal directions—whereby there is a psychological self-selection toward certain ideologies—need to be empirical and theoretically addressed. Another excellent example of this careful attention to experimental design is a ground-breaking study by Krosch and Amodio (Reference Krosch and Amodio2019). The researchers used EEG and fMRI to demonstrate that under conditions of scarcity, White participants exhibit deficits in face processing such that Black faces are visually encoded less accurately as human faces. By adapting a common resource allocation task and incorporating measures of facial processing under conditions of scarcity and nonscarcity, Krosch and Amodio were able to show how situational conditions can moderate the relationship between neurocognitive processes and ideological phenomena (tackling the “neurocognition → ideology” equation, with attention to the interaction with situations). Thoughtful experimental design can therefore disambiguate between the directionality of such causal relationships and delineate the conditions under which they operate.

Isolating the causal directions, as well as the feasibility of measuring the neural and behavioral manifestations of ideological thought, can also falsify certain hypotheses within the “neurocognition → ideology” or “ideology → neurocognition” equation. A recent study by Bakker and colleagues (Reference Bakker, Schumacher, Gothreau and Arceneaux2020) found that conservatives and liberals exhibit similar physiological responses to threats—despite prominent earlier studies suggesting neurophysiological differences (Oxley et al., Reference Oxley, Smith, Alford, Hibbing, Miller, Scalora, Hatemi and Hibbing2008). This productive replication attempt raises a multitude of questions about the impact of ideologies on neurophysiology and highlights the importance of methodologically sound scientific endeavors to explore theoretical claims. It illustrates that there may be critical specificities in the kind of neurocognitive and physiological processes that are shaped by ideology, and points to the importance of careful assessment of potential situational moderators or other psychological individual differences. The neurocognitive model of ideological thinking can therefore provide a useful framework for conceptualizing such research and offer a theoretical platform for potential falsifications or empirical modifications of the links between ideology and neurocognitive processes.

Conclusions

“What totalitarian ideologies therefore aim at is not the transformation of the outside world … but the transformation of human nature itself,” Arendt wrote in The Origins of Totalitarianism (Reference Arendt1951, p. 458). She thus captured a crucial idea that has often been overlooked in the social and political sciences—to understand ideologies we must examine their effects on unobservable cognitive processes and not simply observable behavior and external political structures. The neurocognitive model of ideological thinking proposed here elaborates on the underlying mechanisms by which ideologies attract and compel the minds of followers. It posits that individuals’ ideological worldviews can reflect their existing neurocognitive dispositions and that ideological systems can shape low-level perceptual and cognitive systems. Temporary or chronic experiences of stress, intergroup conflict, or motivational crises in meaning can amplify or alter the expression of neurocognitive processes, and thus shape ideological behavior. Hence, while it may be insufficient to concentrate solely on (1) the roles of forceful homogenizing situations (i.e., the “situational” model of ideological behavior) or (2) the motivational basis of ideological action (i.e., the “motivational” model), we can develop a comprehensive framework by integrating these ideas through the insights of cognitive psychology and neurobiology.

A neurocognitive model of ideologically motivated thoughts and actions therefore has the power to illustrate that ideological positions have neurobiological foundations and synthesize the array of recent neuroscientific and cognitive research under testable theories and hypotheses (Alford et al., 2005; Batrićević & Littvay, Reference Batrićević and Littvay2017; Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Baker and Dawes2008; Hatemi & McDermott, Reference Hatemi and McDermott2012a, Reference Hatemi and McDermott2012b; Ksiazkiewicz & Krueger, Reference Ksiazkiewicz and Krueger2017; Leong et al., Reference Leong, Chen, Willer and Zaki2020; Nam et al., Reference Nam, Jost and Feldman2017; Zmigrod & Tsakiris, Reference Zmigrod and Tsakiris2021). The model is sensitive to causal relationships, aware of bidirectional links between environments and mental processes, and able to give a language of mediating (Ksiazkiewicz et al., Reference Ksiazkiewicz, Ludeke and Krueger2016; Oskarsson et al., Reference Oskarsson, Cesarini, Dawes, Fowler, Johannesson, Magnusson and Teorell2015) and moderating mechanisms to the complex research on the genetics of ideological orientations (e.g., Dawes & Weinschenk, Reference Dawes and Weinschenk2020; Hatemi et al., Reference Hatemi, Medland, Klemmensen, Oskarsson, Littvay, Dawes, Verhulst, McDermott, Nørgaard, Klofstad, Christensen, Johannesson, Magnusson, Eaves and Martin2014; Twito & Knafo-Noam, Reference Twito and Knafo-Noam2020). In what ways do genes that shape cognition and perception have downstream effects to ideological behavior? Do genes that code for environmental reactivity make an individual particularly susceptible to compelling ideological movements? Breaking down the heritability of political ideology—and evaluating other aspects of ideology such as dogmatism, extremity, and interpersonal hostility—will allow for a more informative biology of ideology. Notably, research from within the biopolitics field has illustrated that attributing ideological processes to biology can help promote political tolerance (Baker & Haas, Reference Baker and Haas2020; however, see Suhay et al., Reference Suhay, Brandt and Proulx2017); conducting this science can therefore have positive spillovers into the wider world.

Cutting-edge research at the intersection of the political and biological sciences is now enabling us to ask new questions. What neurobiological factors determine an individual’s receptivity or resistance to ideological systems? What are the neurocognitive advantages and dangers of strong engagement with ideologies? And when does the mission of the ideology matter? These socially pertinent questions have the power to augment our grasp both of politics and of the brain, and to elucidate the nature of the “ideological brain.” A neurocognitive approach to ideologies will therefore allow us to explore timeless paradoxes as well as the origins of contemporary social issues—paving the way for an informed and informative understanding of the roles of biology and experience in shaping citizens’ private ideological beliefs.