Introduction

In Indonesia, the world's largest Muslim-majority democracy, a prominent Christian mayoral candidate in the country's capital city of Jakarta was convicted in 2017 for alleged blasphemy against Islam, drawing attention to the heavily debated relationship between religious practice and political participation. The World Values Survey (WVS) indicates that more than 62% of Indonesians attend religious services in mosques or churches at least once a week—a level that has stayed consistent in WVS results for twenty years and is substantially higher than most other countries surveyed. Other WVS data show that Indonesians have more frequent social interactions than individuals in any other country (Lussier Reference Lussier2016). Houses of worship constitute a significant node in most Indonesians' very active social networks, raising important questions about the role religious spaces play in fostering political attitudes and behaviors. How are political messages conveyed in religious spaces? What role do religious actors play in legitimating political messages? What similarities and differences exist between the messages conveyed in mosques and churches?

Despite the widespread belief that religion serves as a motivator of political behavior in Muslim-majority contexts, we have very little evidence about how political messaging takes place in sacred spaces. Most existing studies linking religious practice and political engagement come from the study of Christian churches in the United States (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; Djupe and Grant, Reference Djupe and Grant2001; Djupe and Gilbert, Reference Djupe and Gilbert2006) or other Christian-majority locations (McClendon and Riedl, Reference McClendon and Riedl2019; Smith, Reference Smith2019), while a growing literature looks at Muslim political participation in the United States or Europe (Chouhoud et al., Reference Chouhoud, Dana and Barreto2019; Westfall, Reference Westfall2019). As Chouhoud et al. (Reference Chouhoud, Dana and Barreto2019) note, analysis of non-Christian denominational differences in the study of political participation is sparse. This study builds upon this existing literature to examine the presence and nature of political messages across Muslim and Christian religious contexts in a Muslim-majority country. As both a Muslim-majority democracy and the world's largest Muslim-majority country, Indonesia constitutes a crucial case for studying potential links between the state, religious institutions, and the legitimation of religiously based political appeals.

This article examines the role of houses of worship in shaping political messages during elections in 2017 and 2019. A controversy that began during the 2017 electoral campaign contributed to a heightened politicization of religion in the electoral context, which state actors sought to neutralize prior to the general election in 2019. The forthcoming analysis describes these dynamics and analyzes sermons that took place in houses of worship against this broader context. Our participant observation of 71 sermons in twelve houses of worship in the city of Yogyakarta—a more typical Indonesian city than the country's capital—provides insights into the frequency, style, tone, and consistency of political content in mosques and churches prior to an election.

We find that in 2017, pre-electoral political messaging was common, though oblique, among mosques, while messages in churches focused on broad support for electoral participation. Political messaging was more frequent in 2019 yet remained indirect and largely neutral in tone. In both 2017 and 2019 we observed that political messages within individual houses of worship were often inconsistent from week to week, reducing their potential as a mobilizing force for political action. This finding was particularly true among mosques. Lastly, our observations revealed that houses of worship frequently sought to present themselves as politically free or neutral spaces in an electoral context in which religious themes or messages had become highly politicized. This observation raises valuable questions about the broader role played by religious institutions in contexts where religious appeals are invoked by political actors.

Political messages and houses of worship

As spaces where individuals who share common values congregate and develop meaningful networks of trust, houses of worship can serve as an important locus for the diffusion of political information and political mobilization. Most research on the role of houses of worship in mobilizing political action has focused on predominantly Christian democracies. Within this body of work, there are several findings that highlight the role of churches in fostering political engagement. In short, the literature finds that churches provide a forum where individuals can be exposed to political messages; serve as an access or entry point for congregants to interact more broadly with political causes; and expand individuals' social networks, thereby increasing the likelihood of political mobilization (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; Smidt, Reference Smidt1999; Brown and Brown, Reference Brown and Brown2003; Djupe and Gilbert, Reference Djupe and Gilbert2006).

As Westfall (Reference Westfall2019, 683) contends, the robust literature on Christianity demonstrates a broad consensus that attending church has at least some indirect effect on civic engagement and political participation, and that the mechanism behind this relationship comes primarily from group dynamics rather than specific denominational principles. Consequently, the theoretical connection between religious practice and political participation is independent of the content of religious beliefs, although research that accepts this premise and examines the relationship across religious traditions is rare. In general, there is little reason to expect that mosques and churches should look fundamentally different regarding their ability to expose worshippers to political messages. While the structure of worship is different in Christian and Islamic traditions, both practices emphasize communal worship and fellowship among co-religionists; both prize sacred texts as a source of guidance; and both include a sermon by a religious leader at a weekly worship service. Individual churches or mosques might place restrictions on the extent to which preachers may touch on political themes in their sermons—such as prohibiting the direct endorsement of political candidates—but such restrictions do not correlate more strongly with one type of tradition or another.

Despite extensive rhetoric about mosques as a source of possible radicalization (particularly in European Muslim minority communities), mosques are rarely analyzed directly in work examining Islam and political mobilization. An emerging literature aims to consider their role as mediators between religious practice and political participation. Much of the empirical work is focused on mosques in Muslim-minority countries (Jamal, Reference Jamal2005; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Gasim and Patterson2011; Dana et al., Reference Dana, Barreto and Oskooii2011; Smits and Ultee, Reference Smits and Ultee2013; Sobolewska et al., Reference Sobolewska, Fisher, Heath and Sanders2015; Fleischmann et al., Reference Fleischmann, Martinovic and Böhm2016; Westfall, Reference Westfall2019). Within this scholarship, several findings point to the possibility that the functional role played by churches in serving as conduits for civic and political engagement may be present in mosques as well. Chouhoud et al. (Reference Chouhoud, Dana and Barreto2019) and Westfall (Reference Westfall2019), for example, both find that mosque involvement is a positive predictor of Muslim political participation in the United States. In one of the few examinations of mosques in Muslim-majority contexts, Butt's (Reference Butt2016) study of Friday prayers in Pakistan notes that the sermon can serve to motivate worshippers to participate in political opportunities.

Empirical analyses of both churches and mosques regularly rely on large-N surveys of either worshippers or clergy members to seek out statistically significant correlations between measures of religious practice and political engagement. Scholars continue to debate the mechanisms responsible for these correlations. Some work focuses on clergy as the unit of analysis, considering worshipper responses to signals issued by individuals in positions of religious authority (Smith Reference Smith2016, Reference Smith2019; Glazier, Reference Glazier2018). Scholarship taking this approach has offered a range of findings about the specific impact of clerical messaging, including where it is more likely to occur and be effective. Glazier's (Reference Glazier2015, Reference Glazier2018) work on Christian clergy in the United States points to several significant findings, including that clergy are more likely to deliver political messages in sermons if they are part of larger congregations with a history of engagement (2018), that conservative clergy are more likely to engage in election-specific activities (2018), and that American Christians who are “providential believers” are significantly more likely to participate when they hear political sermons from their clergy (2015). Smith's (Reference Smith2019) study of Christian clergy in Latin America finds clerics can shape political attitudes and behaviors of worshippers on topics related to core religious concerns but are less influential in guiding vote choice.

In their analysis of sermons preached in Christian communities in sub-Saharan Africa, McClendon and Reidl (Reference McClendon and Riedl2019) argue that exposure to messages through sermons affects political participation by providing metaphysical instruction that affects how listeners respond to political opportunities. While they identify different emphases in approaches taken by Pentecostal sermons versus Catholic and Mainline Protestant sermons, their overall finding is that repeated messages have an additive effect on worshippers' motivation for political participation. In exploring the mechanism that translates messages into action, they argue that individuals are exposed to different interpretive maps that they selectively draw on (2019, 28), suggesting a more complex method of diffusion than a simplified model of worshippers following cues issued by individuals in religious authority.

Other scholarship places less emphasis on the clergy, focusing instead on the broader social and community influences present at a house of worship where political messages may be conveyed. Djupe and Grant (Reference Djupe and Grant2001) find support for several possible mechanisms that can draw worshippers into political engagement, including recruitment by a coreligionist, the presence of political meetings in church spaces, and perceptions of partisan leanings within a congregation. Any of these mechanisms suggest that houses of worship can foster political participation through forms of social diffusion, even if clergy are not delivering direct political messages. Westfall finds that mosque attendance positively affects political participation when congregants engage in social functions at the mosque beyond participation in religious rituals, concluding that “religious participation must proactively engage with the social lives of the congregants to have a substantive political effect” (Reference Westfall2019, 678).

Despite similarities in the function that houses of worship perform regardless of denomination, there are important differences in worship style between Muslim and Christian traditions. Christian practice prioritizes weekly attendance at a Sunday worship service. Additionally, most Indonesian churches (including all included in this study) offer multiple services over Saturday and Sunday, making it easy for members of the community to worship at their primary church of choice every week. In contrast, Islamic traditions prioritize five daily prayers, which may be conducted in a mosque, prayer hall, or private location. Because prayers happen at specific intervals from before sunrise until after nightfall, most observant Muslims find themselves performing their daily prayers at different locations throughout the day. To the extent that they have a primary affiliation with or membership at a mosque, it is generally the mosque that is closest to their house. This is the family mosque where they will also fulfill obligations during Ramadan and celebrate religious feasts. Yet, for observant Muslim men, attendance at midday prayers on Friday—the only time a sermon is included as part of the worship ritual—is also an important religious obligation. Because Friday prayers take place in the middle of the workday, most men who attend Friday prayers in Muslim-majority contexts do so at a mosque near their place of employment. Consequently, most mosques have two types of worshippers: those who live in the neighborhood and worship in the mosque outside of their primary working hours, and those who work near the mosque and attend Friday prayer services.

This fluidity of membership may lead to a different sense of worship community among Christians and Muslims and may also have implications for the diffusion of political appeals across different groups. Christians might feel a deeper sense of community at a single worship space, allowing them to develop stronger social networks within that space and making them more susceptible to political messages and mobilization appeals received through that community. In contrast, if the average Muslim man is dividing his worship time between two different mosques, his ability to develop dense social networks in either community might be more limited, reducing the likelihood that he will be mobilized politically through a worship community. Yet, an alternate hypothesis is also plausible: perhaps his participation in more than one house of worship is exposing him to a broader range of social networks that would increase his likelihood of political mobilization. For example, if an individual's neighborhood mosque rarely communicates political information, but the mosque he attends for Friday prayers engages political themes more consistently, he might become drawn into political engagement from that second mosque alone. If houses of worship expose worshippers to political information that they use to inform political participation that is not mobilized by worship networks, then one's own sense of connection to the worship community is irrelevant: mosques and churches are equally capable of exposing worshippers to these messages.

Indonesia serves as a valuable case for examining the presence of political messaging among Muslims. It is the largest Muslim-majority country in the world and has established the most stable electorally competitive political system among Muslim-majority states. Freedom of speech and assembly are largely protected, and there are no significant barriers to political formation. In this context, we should expect minimal risk to religious leaders who choose to communicate political information or opinions to members of their communities. Indonesia also occupies an interesting place regarding the relationship between religion and state. While not fully secular, Indonesia has a long tradition of religious tolerance and six religions enjoy official recognition and protection by the Indonesian Constitution: Islam, Catholicism, Protestantism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. According to the Indonesian Ministry of Internal Affairs (as reported in dataindonesia.id), at the end of 2021, 86.9% of Indonesians identified as Muslim, 7.5% as Protestant, 3.1% as Catholic, and the remaining 2.5% identified as Hindu, Buddhist, or Confucian.Footnote 1 Muslims comprise the majority of religious adherents in most provinces, yet the presence of a sizeable Christian minority makes it possible to examine political appeals across both Muslim and Christian houses of worship.Footnote 2

The relationship between Islam and the state in Indonesia is politically complex. A substantial contingent of Indonesian Muslims seeks a greater role for the formal incorporation of religion in the state. Over the past two decades, greater calls for the Islamization of the Indonesian state have generally been accomplished through the adoption of religious bylaws at the local level, as part of a political conflict that regularly involves both Islamist and secular parties (Buehler, Reference Buehler2016). In short, the most significant debates about state incorporation of religion occur at the local level. Local governments have come to play an increasingly important role in distributing state resources and administering public services, giving mayors and district heads greater degrees of power over the past twenty years. Against this background, elections for local executives, such as those held in 2017, are of significant political consequence. A controversy that began during the Jakarta gubernatorial race in 2017 politicized religion and heightened social tensions to such an extent that bureaucrats and religious leaders sought a greater separation of politics from sacred spaces prior to the general election in 2019.

Mayoral election 2017

In February 2017, Indonesia held 101 elections for local and regional executives. Jakarta's gubernatorial race gained international attention. Incumbent Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, commonly known as “Ahok,” sought election to the position he had held since it was vacated by Joko Widodo's ascent to the Indonesian presidency in 2014. A Christian, Ahok was also the first ethnically Chinese person to govern the capital city and enjoyed considerable popular support for his efficient governing style. While campaigning in September 2016 Ahok—who had a reputation for making impolitic statements—referenced a verse from the Qu'ran. Public protests orchestrated in part by the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), a militant Islamist organization frequently implicated in religiously motivated violence, immediately followed, leading to formal charges of blasphemy. The trial unfolded throughout the campaign. Ultimately, Ahok, who was supported by the nationalist Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), lost the election, was found guilty of blasphemy, and was sentenced to two years in prison. The blasphemy controversy dominated all aspects of the Jakarta election and commanded national attention, as many saw it as a litmus test for the boundaries of free speech and religious tolerance across Indonesia.

As the Ahok controversy dominated headlines, an intense mayoral contest unfolded in Yogyakarta, a medium-sized city with an estimated population of about 400,000. Yogyakarta's incumbent mayor, Haryadi Suyuti, sought reelection while running against his deputy mayor, Imam Priyono. With fewer than 1,200 votes out of almost 200,000 separating the candidates, it took two months for Haryadi to be declared the winner. This local context, which represents a more typical instance of Indonesian politics than the Jakarta gubernatorial election, provides the case study for our analysis on political messages. Located in central Java, Yogyakarta is the capital of a province with a total population of about 3.4 million. The city is a center of higher education, attracting a significant number of Indonesians from outside Java to the region and contributing to meaningful ethnic and religious pluralism. Additionally, Yogyakarta has a long history of religious tolerance, fostering the development of strong worship communities that operate openly without fear of reprisal.

To examine the potential role of political messaging in houses of worship, we conducted participant observation at eight mosques and four churches in Yogyakarta in the month before the election. We selected mosques and churches that are representative of the organizational, theological, geographic, and political diversity found in the city. Among Islamic traditions, this diversity includes the strong, visible presence of the modernist Muhammadiyah organization; a weaker (but still visible) presence of the traditionalist Nadhlatul Ulama (NU) organization; and the existence of specific Javanese religious and ceremonial customs related to the region's sultanate that contribute to a more syncretic religious practice commonly referred to as kejawan. Muhammadiyah, NU, and kejawan groups can all be described as generally moderate and largely tolerant toward both each other and religious minorities. In recent years, however, there has been an increase in the presence of more radical and intolerant Salafist groups and preachers in the city. As a result, Yogyakarta is now experiencing an intense contestation over who “speaks” for Islam. Christians, meanwhile, comprise the most significant religious minorities in Yogyakarta. The largest mainline Protestant denomination is the Christian Church of Java (Gereja Kristen Jawa, henceforth GKJ), a Presbyterian denomination. The Pentecostal Church of Indonesia is the largest evangelical denomination. The city also has seven Catholic parishes.

Twelve political parties competed in the 2014 national legislative elections. In Yogyakarta, two political parties, the nationalist Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) and the United Development Party (PPP), have longstanding, deep support within the population. These two parties are anchors of an ideological split between secular, nationalist parties and parties organized around Islam, a split frequently described by Indonesians as the struggle between the nationalist “red” group and the Islamic “green” group. PDI-P, PPP, and other smaller parties mapped onto the 2017 mayoral contest such that the incumbent mayor, Haryadi, enjoyed the support of the “green” Islamic-oriented groups, while his opponent was supported by “red” nationalists.

Information about the mosques and churches selected for participant observation is in the Appendix. To protect their privacy, we have chosen not to identify them by their names, but rather have assigned them each a number. Collectively, they provide a cross-section of houses of worship that represent the range of mosques and churches commonly found in Yogyakarta regarding size, structure, and religious affiliation. They were also selected to ensure geographic diversity within the city, and to account for neighborhoods that have a long history of support for specific political parties.

For the four weeks before the February 17 vote took place, thirteen trained master's students in the program for Religious and Cross-Cultural Studies at the University of Gadjah Mada attended Friday prayers at the mosques and Sunday services at the churches to gather information about whether political messaging was taking place during worship services.Footnote 3 These research assistants documented a broad range of information, such as: (1) the content of sermons delivered, including specific attention to direct mobilization appeals or any indirect advocacy of a political outcome through discussion of socioeconomic or political concerns; (2) announcements that reveal election-related activities organized by the house of worship; and (3) description of indirect indicators of political mobilization, including the presence of campaign materials or volunteers in or around the house of worship. All research assistants wrote detailed field notes of their observations, which serve as the primary documents used for analysis. Their notes provide us with information on 47 sermonsFootnote 4 given in mosques and churches, as well as information about political messages provided through other means, such as prayer intentions, bulletins, or leaflets, as well as visible forms of support, such as partisan or campaign materials.

General election 2019

Indonesia held elections for president, the national House of Representatives (DPR), House of Regional Representatives (DPD), and subnational houses of representatives on April 17, 2019. It was the most complex election in Indonesian history, with more than 190 million eligible voters casting ballots for more than 28,000 offices across the country.

Following the Ahok controversy of 2017 and the politicization of religion that resulted, parts of the state bureaucracy, religious actors, and political figures sought mechanisms to reduce the likelihood of an escalation of social conflict in 2019. Following the April 2017 run-off election for Jakarta mayor, the Indonesian Ministry of Internal Affairs (MORA) issued an “appeal” regarding the content of sermons in houses of worship. Among the nine points listed in the statement, one included “The material presented is not charged with practical political campaigns or business promotions” (Kuwado, Reference Kuwado2017). A recommendation entitled “Free Houses of Worship from Political Debate and Hatred” issued by the Indonesian Council of Ulama (MUI) in early May 2017 further elaborated on the Ministry's appeal. Similarly, members of the Council of Indonesian Mosques made numerous statements encouraging political neutrality and pluralism in mosques. All these directives appeared aimed at neutralizing the politicization of religion in electoral politics that exploded with the Ahok controversy.

The MORA also tried to prevent a reoccurrence of the 2017 scenario by staking out a clear position against the politicization of religion and use of houses of worship for political purposes well in advance of 2019. As early as February 2018, Minister of Religious Affairs Lukman Hakim Saifuddin spoke out against the politicization of religion, stating,

“For example, in houses of worship those who preach ‘vote for pair A, don't vote for pair B,’ or even more extreme, preaching that in this mosque or in this church it is only allowed to support A, that is manipulation, it cannot be exclusive like this…However, if the appeal is to vote for the pair or party that is against corruption, this is good, because religion strictly forbids this crime.” (Saubani, Reference Saubani2018)

Saifuddin appears in several media articles reinforcing similar themes throughout 2018. He also showed support for the use of houses of worship by the KPU for voter education purposes (Ariefana and Aranditio, Reference Ariefana and Aranditio2019).

In advance of the 2019 presidential elections, the Central Election Commission (KPU) further clarified that houses of worship were allowed to participate in KPU events involving “election socialization,” which is perhaps best understood as voter education. These events typically provide basic information to voters, such as which offices will be voted on in the election, who the candidates are, what the ballot will look like, how to correctly mark a ballot, and further information about polling locations and hours. According to KPU Head Arief Budiman, “If a campaign activity is conducted by a participant in the election, this activity cannot be carried out in a government building or a house of worship. If socialization is being conducted by the KPU, this can take place anywhere” (CNN KPU Janji Sosialisasi Pemilu di Rumah Ibadah Bukan Kampanye, 2019). In sum, the signals from both MORA and the KPU indicated that houses of worship should be thinking carefully about how to keep politics out of sacred spaces going into the 2019 campaign period.

Similarly, religious organizations issued statements that supported a peaceful electoral process. In March 2018, Muhammadiyah and NU issued a joint statement about politics that encouraged people to participate in the elections as part of the democratic process that improves the lives of the country's citizens; discouraged the spreading of false information; affirmed that Pancasila and the current configuration of the Republic of Indonesia were the final framework for the country, and that ethnic, tribal, and religious diversity should be maintained in this framework; and asked the government to lower poverty (Mamduh, Reference Mamduh2018). Both the Indonesian Council of Bishops (KWI) and the Indonesian Communion of Churches (PGI) issued statements on the elections that encouraged voting as well as following a Christian code of ethics and adhering to the electoral process outlined by Indonesian law (Komisi Kerasulan Awam Konferensi Walinegara Indonesia, 2019; Majelis Pekerja Harian Persekutuan Gereja-gereja di Indonesia, 2019).

In addition to statements from MORA and the KPU that sought to draw a firm line between religious practice and political mobilization and supportive statements from prominent religious organizations, Indonesian President Joko Widodo (more commonly known as Jokowi) strategically chose his running mate, Mar'uf Amin, to help blunt a red-green divide.Footnote 5 As Chairman of the MUI, Mar'uf Amin had signed the fatwa in 2016 that had claimed Ahok's words as blasphemous. He was also serving as Supreme Leader of NU prior to joining the ticket. Bringing Amin onto the ticket effectively split Islamic parties' endorsements between Jokowi and opponent Prabowo Subianto, preventing the tenor of the campaign from taking on a nationalist-Islamist frame. Ultimately, President Joko Widodo easily won reelection with a first-round majority vote (55.5 percent).

Given the shift in political context between 2017 and 2019, we have reason to expect religious leaders in 2019 would be more guarded in how they spoke about political themes, particularly regarding elections. In the four weeks prior to the national election, we repeated participant observation of Friday prayers and Sunday sermons in four mosques, one Protestant, and one Catholic church observed in 2017, using the same approach and procedure to observe a total of 24 sermons.

Results: frequent, broad political messages

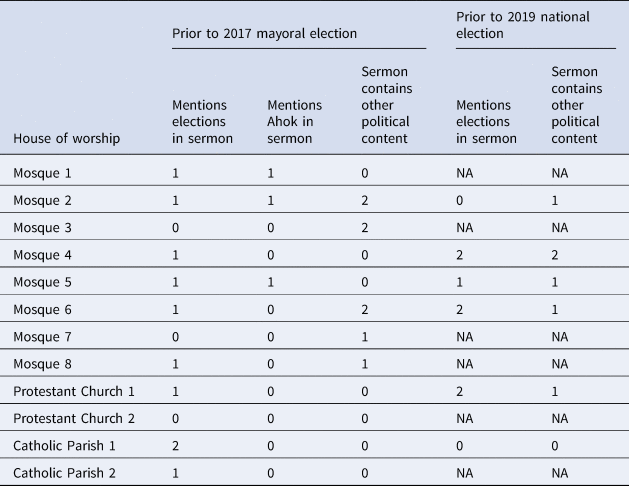

Table 1 provides information about the frequency of political content appearing in sermons across the houses of worship examined in the study, as well as indicators measuring the explicitness and consistency of political messages. Political themes were addressed in more than one-third (38.3 percent) of sermons observed in 2017. The number was higher in 2019, where political themes were observed in 10 out of 24 sermons (41.7 percent). Of the 38 total sermons that included some form of political content, only ten had political themes as the primary topic. In the rest, some political information was communicated, but it was not central to the sermon's theme. In thinking about the potential impact of political messaging on a worshipper's subsequent behavior, we have no reason to believe that the ratio of political to non-political content in a sermon is consequential. Exposure to political information can be brief and still be impactful. Of the twelve houses of worship observed in 2017, only one—Protestant Church 2—provided no mention of political content in sermons during the period of observation. In the smaller 2019 sample, only Catholic Parish 1 had no mention of political content in the observed sermons.

Table 1. Frequency of political content in pre-election sermons

Over both observation periods most churches and mosques averaged one mention of political information in the four-week observation period. However, there were some exceptions to this trend. In 2017, Mosque 2 stood out from the rest with three sermons, all of which included political themes as the primary topic. In 2019, both Mosque 6 and Protestant Church 1 had three sermons with political themes, two of which addressed the elections in each location.

The sermons that included political content covered a range of topics. In 2017, 10 (less than one-quarter) mentioned elections in some capacity, three made specific reference to the Ahok controversy, and six included some other form of political content. Political messages in the churches were more direct and election focused, almost all aimed at encouraging participation. The tone of the messages, however, was restrained, sidestepping direct endorsements or discussion of sensitive political topics. Mosque messages comprised greater variation in tone, exhibiting neutrality, restraint, and provocation. While in several instances preachers in mosques offered clear directives about how worshippers' religious obligations should shape their political actions, in most cases language was subtle. Notably, Muslim preachers who addressed political themes used oblique language that required some interpretation together with further political knowledge to identify a specific directive. For example, one sermon in Mosque 2 focused on the theme of honesty and trust with lots of broad references to greed among political leaders and warnings of corruption. The oblique nature of the messages makes it difficult to discern whether a particular type of message was being consistently reinforced in a single house of worship. This pattern of oblique messaging reflects broader societal variation in how to respond to the Ahok controversy and whether the events merited a criminal case.

In 2019, seven sermons (about one-third) mentioned the elections and four included other political topics, suggesting an overall increase in pre-electoral political content in sermons between the two periods. While the smaller sample size in 2019 limits us from generalizing broadly, we continue to observe that messages in churches were direct and sought to encourage participation while mosque messages were more diverse, but also largely broad and restrained. For example, the one sermon in Mosque 5 that included a political message focused directly on the elections to provide a call for tolerance. The preacher cautioned against letting politics and political differences create division within families and communities, noting that this type of discord can keep people out of heaven.

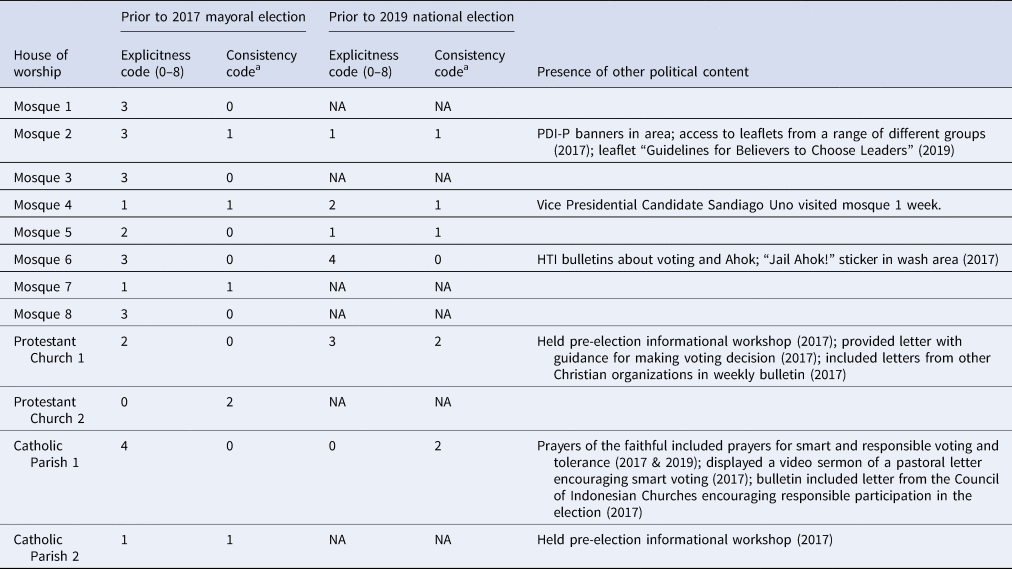

To better understand if political messages observed could provide a map for political action, we developed two codes. First, we coded individual sermons by their level of explicit direction. Sermons where there was no political content were coded as “0.” Sermons where the political message was broad and did not signal a clear direction of actions were coded as “1,” and sermons with an explicit direction for action were coded as “2.” We then aggregated the scores across sermons for each house of worship to develop an overall level of explicitness that can allow us to consider the extent to which political messages are present and directed in houses of worship. A house of worship with a score of “0” never experienced a political message, while a score of “8” signifies direct political messages in every sermon. Scores between these two endpoints represent a mix of both frequency and directionality. Variation in explicitness scores serves as the basis for a measure of the consistency of political messages. Both scores are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Explicitness, consistency, and range of political content

The same sermon may be entered in more than one column above if the content applies to multiple categories.

Explicitness code is aggregated over all sermons. Individual sermon code: 0 = no political content; 1 = broad, indirect political content; 2 = explicit political direction.

a Consistency code: 0 = sharply inconsistent messages across sermons; 1 = slightly inconsistent messages; 2 = consistent messages.

Analysis of these two variables reveals three interesting trends. First, although the theoretical range of the explicitness variable is “0” to “8,” the highest aggregate explicitness score observed in both time periods is “4,” suggesting that very few sermons contained explicit messages. Only nine such sermons out of 71 total included an explicit political message, and in each instance the message involved a directive about voting. The house of worship with the highest explicitness score in 2017 was a Catholic parish, in which priests called on worshippers in two different sermons to vote in the upcoming elections, not be apathetic, and educate themselves on the issues. In 2019, Mosque 6 is coded with the highest explicitness score, reflecting political content in three sermons and an explicit directive in one sermon to not select Jews or Christians as leaders.

Second, we found a broad cross-section of messages appearing in the five mosques with explicitness scores of “3” in 2017. One sermon each in Mosque 1, Mosque 3, Mosque 6, and Mosque 8 called directly on worshippers to support Muslim candidates. A sermon in Mosque 5 took a slightly different approach, criticizing vote buying and calling on people to prove that Muslims are worthy enough to serve in elected capacities. All other sermons containing political content in the mosques were broader, containing discussion of values and principles in more abstract terms.

Third, the consistency coding reveals that more than half of the houses of worship in our 2017 sample showed sharp inconsistency in political messaging. Inconsistency in the type of political messages revealed in sermons, coupled with the opaqueness of several messages, suggests that political content contained within sermons in houses of worship are an unlikely mobilizing force for political action absent other contextual factors to assist in converting political themes into action. The greatest consistency in messaging we observed was in churches: both Protestant Church 2 in 2017 and Catholic Parish 1 in 2019 were consistently non-political, while in 2019 Protestant Church 2 showed consistent encouragement of electoral participation. These patterns reveal that explicit, direct messaging was not the modal form of political content contained in sermons. Typically, a specific directive for action was issued only once in a house of worship in a four-week period.

When we consider the broader regulatory and organizational framework in which sermons are embedded, the lack of direct endorsement and inconsistency in messaging is logical. Even prior to the Ahok controversy, many mosques, such as the highly political Mosque 6, had specific policies or norms that regulate the content of sermons. Preachers who are invited to give sermons at this mosque are informed that they are not allowed to make political endorsements or show signs of support for specific parties. They are, however, allowed to provide political commentary more broadly. Similarly, the Catholic Church prohibits direct political endorsement, but allows preachers to discuss issues of social importance, which are often political in nature. Moreover, the rotation of preachers is common in both mosques and churches in Yogyakarta. Mosques frequently invite preachers from outside their communities to preach during Friday prayers. We were able to identify the preacher in 27 of the 31 mosque sermons observed in 2017, and no individual ever preached at a mosque more than once in the observation period. Under these conditions, it is highly unlikely that an invited preacher would know what was preached in the previous week, making it difficult for a political message to be consistently repeated.

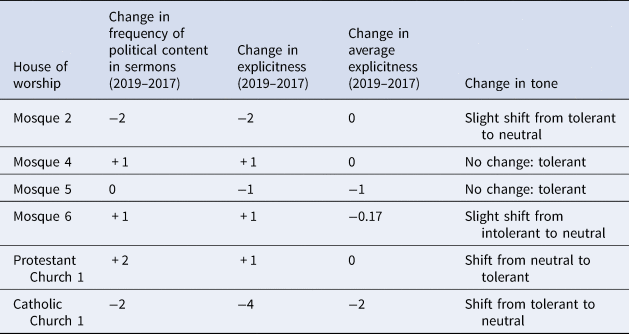

Comparing details from the six houses of worship observed in both 2017 and 2019 can allow us to consider possible change over time within the same house of worship. Table 3 examines changes in the frequency of political content in sermons, the level of explicitness, and tone across each house of worship. While it is impossible to make broad generalizations over only six cases, the information in Table 3 suggests that the inclusion of pre-electoral political content in religious sermons is a fluid and dynamic process, even in a context of heightened bureaucratic warnings against political speech. While two houses of worship had fewer sermons with political themes in 2019, three had more. Overall levels of explicitness went up in three houses of worship and down in three, yet this dynamic is largely connected to the overall change in the frequency of political content in sermons. When we look at an alternate measure that captures the average level of explicitness over all sermons with political content, we observe minimal change in all houses of worship except Catholic Parish 1. This house of worship included no political content in sermons in 2019. Overall, we observe a slight shift in tone toward more neutral positions. In two cases, the houses of worship change from expressing more tolerant positions in 2017 to more neutral positions in 2019, and in one instance, we observe a slight change from an intolerant to a neutral position. The dynamic process this small sample reveals indicates that houses of worship may shift their positions in reaction to the broader local and national political context. In instances when politics may crowd out religious devotion, a push toward neutrality may be more likely. In contrast, if houses of worship feel as though their practices may be threatened by political action or actors, they may take a more active stance in providing political content or encouraging participation.

Table 3. Cross-temporal variation

Sermon themes and other political content

A closer look at the content of specific sermons, as well as consideration of supplementary information, can shed further light on these trends. While reference to the upcoming elections was a common theme in many of the sermons that included political content, the only candidate ever mentioned by name in either 2017 or 2019 was Ahok—who was running for election in a city where none of the worshippers would be voting. Our sermon monitoring revealed that the Ahok controversy became a framing mechanism for broader evaluations of political leadership in 2017. As part of a sermon on fellowship and relations with others at Mosque 3, the preacher noted the need for unity, including good relations with non-Muslims. One especially lengthy sermon at Mosque 6 made a veiled reference to Ahok without using his name. In this instance, the preacher identified Jews, Christians, polytheists, and communists as infidels, warning worshippers not to vote for leaders who are infidels. This sermon, which we believe was delivered by a sympathizer of the radical Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia organization, included the harshest and most condemning language of any sermon we observed. Notably, a similar sermon was delivered in Mosque 6 again in 2019, although we were unable to confirm if it was the same preacher.

Other oblique references to Ahok in 2017, while still encouraging pro-Muslim voting practices, were softer in tone. In a sermon at Mosque 1 that touched on elections, the preacher encouraged listeners to “select and prioritize a fellow Muslim compared to another; raise the level of loyalty to fellow Muslims.” A preacher at Mosque 4 warned that individuals who vote for infidels are hypocrites, and a preacher at Mosque 8 told worshippers not to vote for a non-Muslim candidate. What is particularly noteworthy about these directives is that both candidates running for Yogyakarta mayor were Muslim, making religious identification irrelevant to vote choice.

Overall, churches were more restrained in their inclusion of political content in sermons. As Christians comprise a religious minority in Yogyakarta, this restraint and caution are not surprising. In 2017, none of the church sermons discussed the Ahok controversy directly or indirectly. While Protestant Church 2 did not mention elections in any sermon, the remaining churches touched on them in at least one sermon, and often provided additional information in the form of bulletins or in prayers. Worship leaders regularly offered prayers for the success of the forthcoming elections. For example, while there was no mention of the elections in sermons in 2019 in Catholic Parish 1, the universal prayer in each of the four weeks of observation contained some form of a prayer for the success of the election and active participation in it. Beyond this messaging, some of the Christian parishes took a more involved role in voter education and direction. Both Catholic Parish 2 and Protestant Church 1 organized voter education workshops for their worshippers in 2017.Footnote 6 The Protestant Church 1 workshop, which one of our research assistants observed, was nonpartisan in nature and aimed to provide worshippers with guidance about making thoughtful voting decisions. The minister who led the workshop emphasized that the church does not have political interests and does not become involved in politics on a practical level. Rather, its goal is to equip citizens to make voting decisions consistent with their Christian values by encouraging them to learn about the candidates and their platforms.

On the last Sunday before the elections in 2017, Protestant Church 1 printed a two-page letter from the Church Council in the church bulletin. The letter offered specific voting instructions, including selecting candidates that are nationalist, candidates that are committed to multiculturalism and pluralism, candidates that are committed to maintaining Yogyakarta's unique culture, and candidates from political parties that support these values. Following these points, the letter continued, “To ensure that Christians are not mistaken in making their choices, below are the parties supporting each candidate pair,” with the names and parties listed explicitly. The letter concluded with a direction “DO NOT ABSTAIN” in bold, capital typeface. While the language in this directive is nonpartisan in nature, it was clear that the “nationalist” candidate the church had in mind was the one supported by the PDI-P party. We did not find a similar document in 2019 and might speculate that the church wanted to ensure that it stayed within the boundaries set by MORA about political speech. In 2019, elections were discussed in two of the sermons observed in Protestant Church 1, suggesting a shift in approach. In the final sermon before the election, the preacher spoke extensively about the importance of the elections and encouraged voters to research candidates to determine who would best carry out the work of God.

Other sermons in both years did not make specific reference to elections, but nevertheless included political content that worshippers might take into consideration when voting. For example, in 2017 one sermon at Mosque 2 discussed the importance of honesty and trust in leadership, offering a critique of corruption, and a second sermon emphasized the compatibility of Islam and nationalism. While the preacher did not mention any specific individuals or parties, one could interpret that second sermon as providing a justification for voters to select candidates from the nationalist PDI-P party, which is very popular in the neighborhood where the mosque is located—and was also the party supporting Ahok in Jakarta. In 2019, the one sermon at Mosque 2 that touched on a political theme was focused on the negative impacts of corruption and the need to disavow all corrupt practices. A 2019 sermon at Mosque 6 reminded worshippers that “the matter of choosing a president is not number one. Remember that. God's command is to obey God, that is number one.”

While it is impossible to infer the intent behind preachers' specific messages, existing scholarship offers some suggestions about how and when clergy choose to make political statements. Glazier finds that most explanations for a clergy member's decision to engage politically—including making political statements in sermons—can be categorized into either theological or contextual explanations (Reference Glazier2018, p. 762). Smith (Reference Smith2016) contends that some Christian clergy change the topics of preaching in response to perceived religious competition or policy-based threats and secularization. Smith (Reference Smith2019) also finds that citizen resistance limits what clergy can say from the pulpit, as well as how much congregations can influence their members. These factors could help explain why some clergy in Yogyakarta chose to incorporate political messages—or refrain from them—as well as the tone of the messages. In particular, the overall trend to speak about the elections in neutral or tolerant terms in both mosques and churches in 2019 speaks to the broader national context and a desire to not let political differences overshadow religious values and observance. Both observation periods point to meaningful variation within mosque communities about how to respond to the broader politicization of religion within the electoral sphere, while also revealing a general tendency to not contribute to broader societal discord. Perhaps some houses of worship—both mosques and churches—felt the need to present neutral positions to not alienate regular worshippers or invite greater political scrutiny into their internal affairs.

There are several plausible explanations for clerical references to the Ahok controversy in the 2017 Yogyakarta mayoral election. First, religious leaders may have wanted to address the topic of religious beliefs and political leadership in Muslim-majority Indonesia, using the specific case of Ahok and the Jakarta mayor's race as an example to evaluate the appropriateness of non-Muslims holding political office in a Muslim-majority country. Second, they may have hoped to offer ethical guidance on what constitutes blasphemy by encouraging listeners to consider a full range of words and actions in evaluating others. Third, preachers may have aimed to tarnish the political prospects of the party endorsing Ahok (PDI-P) in hopes of elevating the electoral mandate of Muslim parties. Lastly, perhaps they hoped to use the controversy as an opportunity to further stake a political position regarding the policies of Indonesian President Joko Widodo. If a “red” and “green” divide in Indonesian politics stays pronounced at the national level, religious leaders may feel compelled to seize on local opportunities to make their own positions known—whether those are positions in support of greater Islamization of society, or in defense of Indonesia's tradition of pluralism. These plausible interpretations all suggest that political messages, while broad and restrained, may still serve to signal a political cue and preference.

Beyond the inclusion of political themes in sermons, worshippers may encounter political messages in houses of worship in other formats. The final column of Table 2 provides information about the presence of other forms of political information, including the content of specific prayers, written materials that worshippers could take with them, or other materials present in the house of worship. This information, together with the general background about the political dynamic of the neighborhoods where houses of worship are located, provides another layer of information on worshippers' exposure to political information in and around houses of worship. As the information included here demonstrates, political messages are not limited to sermons and bulletins alone.

When a party banner hangs on the exterior wall of a mosque—as was the case in Mosque 2, located in a PDI-P stronghold—preachers do not need to make a specific endorsement. Yet, in the case of this or any other mosque, it is impossible to untangle the directionality of influence. Since Mosque 2 is in an area with a strong Muslim population with deep PDI-P roots, is the banner an example of the mosque trying to influence the neighborhood, or of the neighborhood attempting to influence the mosque? Additionally, some houses of worship have longstanding histories of political activism, such as Mosque 5, which was known as an organizing space for Muslim students opposing the Suharto dictatorship during the 1980s and 1990s, and Mosque 6, which regularly hosts political discussions. During Ramadan in 2016, Mosque 6 held an event for potential mayoral candidates to share their views on Yogyakarta in the next five years, which both final candidates attended. Political diversity and competition are also evident in the neighborhood surrounding Mosque 6, which boasted campaign and party materials for both PPP and PDI-P. The extent to which these houses of worship embrace political discussion and create space for sharing political information is missed by looking only at sermon content.

One Friday observation we made at Mosque 4 in 2019 is testimony to the fluidity of space shared by houses of worship and their surrounding communities and the way in which lines can become blurred. On the first Friday of observation at Mosque 4 we learned that candidate for vice president Sandiago Uno was on a campaign stop in Yogyakarta and would be attending Friday prayers at Mosque 4. Flyers for the campaign event had been posted around the city and the word had spread about his plan to visit Mosque 4, leading to a much larger crowd of worshippers at the mosque than is usual. Campaign staff sold T-shirts on the street just outside of the mosque. Immediately prior to the beginning of the Friday prayers, one of the mosque administrators stood in front of the main entrance to the mosque and, using a microphone, announced Sandiago's entrance and further proclaimed, “Please, let us pray that Prabowo-Sandi are elected!” Sandiago then entered the mosque and the Friday prayer service continued as normal with no mention of political content during the sermon. On the third week of observation a poster for a campaign event for Prabowo-Sandiago was hanging on the mosque bulletin board and during our final week of observation individuals were handed a Prabowo campaign newsletter after leaving the mosque.

This specific course of events over four weeks speaks to the fluidity and complexity of political content in houses of worship. Except for the campaign poster on a mosque bulletin board—which may have been placed there by a resident unknowingly without permission—the mosque itself was kept a politically clean space. Nevertheless, the sequencing of activities pushed the norms of restraint that various entities have requested. One can hardly expect political figures to refrain from fulfilling their religious responsibilities during a campaign stop. Yet, it is impossible to consider Sandiago's very visible and public participation in Friday prayers at this one mosque as not having yielded some possible campaign benefit to his ticket.

The addition of broader contextual information from houses of worship together with sermon content further strengthens our impression that the tone of political messaging between 2017 and 2019 had moved in a more neutral direction. Protestant Church 1 appears to have refrained from a written letter with a veiled voting recommendation and Catholic Parish 1 only referred to the elections in prayers, not in sermons. Most notably, in Mosque 6, we found an interesting set of directions on the bulletin board. Beneath a poster advertising the campaign event that had brought Sandiago Uno to Mosque 2 the previous week was an appeal that individuals coming to the mosque should come without campaign props and not wear any campaign logos on their clothing. The mosque was trying to ensure that campaign supporters remembered that the mosque is a politically neutral place.

We have no baseline to determine what degree of political discussion we might expect in pre-election sermons, making it impossible to determine how our data fit within a greater population of cases. Nevertheless, our observation of activities in houses of worship over two electoral periods found that these spaces remained primarily sacred and not overtly political. While political mobilization did not appear to be a principal objective in any of these houses of worship, political messaging was relatively common and widespread across them.

Conclusion

This article has sought to bridge the lacuna that exists between a robust literature on the relationship between religious practice and political participation in predominantly Christian contexts and studies of mosques in Muslim-minority democracies. Our analysis of sermons in mosques and churches in a typical Indonesian city prior to elections reveals several findings that can help advance further research.

First, political messaging in houses of worship appears widespread among both mosques and churches. While we have no pre-campaign baseline to determine whether the frequency or content of the messaging fits into a normal pattern or was heightened due to the Ahok controversy in Jakarta, this study provides a reference point for future studies of political messaging. Second, our analysis of sermons in both 2017 and 2019 showed that the political messages contained within religious sermons reflected a broad cross-section of ideas, were not very explicit, and were often inconsistent within a single house of worship. This pattern of messaging suggests that political mobilization along religious lines is happening outside of worship spaces, not within them.

Between 2017 and 2019 we further noted a slight shift in tone to neutrality and tolerance. This increase in frequency of political themes and shift in tone in 2019 may reflect broader efforts by religious leaders to counteract the politicization of religion by political actors through the deliberate incorporation of non-partisan discussion that emphasized tolerance and participation. Third, we observed that even when sermons lack political themes, worshippers can still encounter political content through their sacred spaces, either directly through print materials, or through the fluidity with which houses of worship are embedded in broader community structures.

These findings suggest that houses of worship in Indonesia are generally seeking to be politically neutral spaces, even though political content is frequently present in them prior to elections. The politicization of religion is occurring outside of sacred spaces and mosques and churches appear to be reacting to this politicization through a different form of messaging. Both Muslim and Christian leaders are consistently (though not universally) appealing to worshippers to draw on their religious values to support democratic electoral practices and encouraging them to make thoughtful voting decisions.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048324000117.

Financial support

This research was funded in part by a Global Religion Research Initiative International Collaboration Grant issued in 2017 and a Grinnell College Center for Humanities Grant issued in 2018. The funders played no role in the design, execution, analysis or interpretation of data, or in writing of the study.

Competing interests

None.