Introduction

Attempts to diversify political representation, whether for women or ethnic minorities, have been criticized for leaving ethnic minority women behind: ethnic minority women have been found to be excluded from initiatives to boost women’s representation (Krook and Nugent Reference Krook and Nugent2016), and the majority of earliest representatives of people of color were men (which is still the case in many countries, like the United States (US). When the analytical lens of intersectionality started revolutionizing research into descriptive representation, the findings indicated that intersectional membership in two underrepresented groups resulted in extra invisibility and thus double the level of disadvantage. With early work documenting how and where women were experiencing the familiar gender disadvantages in any competition with ethnic minority men, and ethnic disadvantage in competition with white majority women, it has come as a surprise that increasingly in some countries, ethnic minority women experience some representative advantages (Hardy-Fanta et al. Reference Hardy-Fanta, Lien, Pinderhughes and Sierra2016). In fact, in some legislatures, ethnic minority women are better represented descriptively than ethnic minority men (Barker and Coffe Reference Barker and Coffé2018; Celis et al. Reference Celis, Erzeel, Mügge and Damstra2014; Mugge et al. Reference Mügge, van der Pas and van de Wardt2019).

The narrative of double disadvantage quickly turned to the “ticking two boxes” one, which posits that ethnic minority women’s political aspirations are frequently boosted by political party selectors who see their nominations as a double win in their efforts to meet their parties’ gender and ethnic diversity targets (Hughes Reference Hughes2011). As both women and minority, ethnic minority women candidates “satisfy two quota imperatives at once” for political parties (Donovan Reference Donovan2012, 35), which was generally shown to be a result of strategic behavior by political parties (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Erzeel, Mügge and Damstra2014). The narrative of ethnic minority women ticking two boxes, and thus experiencing comparatively more electoral success, has been mostly thought to apply to countries with proportional representation (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Erzeel, Mügge and Damstra2014; Hughes Reference Hughes2016). Curiously, however, the pattern of ethnic minority women being comparatively better represented than minority men has also become true in some majoritarian systems, such as the United Kingdom (UK) (Cracknell Reference Cracknell2017). This means that the strategic imperatives for parties to tick two representative boxes have become strong enough to yield electoral advantages even in systems where seats are relatively a sparser good for parties (i.e., they can only nominate one person for one seat). This indicates that the narrative of ticking two boxes extends to other electoral systems, and illustrates how strong the imperatives for parties to diversify has become. More importantly, it illustrates how intersectionality can explain “multiple identity advantage” (Fraga et al. Reference Fraga, Martinez-Ebers, Lopez, Ramírez and Reingold2008); although proportional representation has been shown to encourage women’s descriptive representation, majoritarian systems have been known to benefit ethnic minorities’ presence in legislatures (Ruedin Reference Ruedin2013). It is clear that in many countries, ethnic minority women can benefit from either or both.

However, does this new positive story of relative representational success mask the fact that the two can coexist? Is double disadvantage based on intersectional group membership still experienced by ethnic minority women politicians despite their increased presence in legislatures? Going beyond the focus on representative outcomes (inclusion or exclusion), in this article, we contribute to the existing literature on intersectionality and political representation by turning our attention to the experiences of ethnic minority women in UK local government. Following Mugge and Erzeel (Reference Mügge and Erzeel2016), who distinguish distinct mechanisms through which minority women realize differential outcomes, such as recruitment, candidate selection, informal networks, and formal and informal rules of representation, we look not only at how these mechanisms contribute to inclusion or exclusion of minority women, but also how they are subjectively experienced by them.

Drawing from 85 interviews with ethnic minority local councillors, candidates, and activists, 38 women and 47 men, we analyze experiences of ethnic minority women at local levels of government. Local government in the UK is a valuable case study, as it is a particularly masculinized political institution with women local councillors often operating in conditions where women’s issues and perspectives are marginalized and less likely to be well received (Childs Reference Childs2023, 511). We also draw attention to heterogeneity among ethnic minority women and how different forms of gendered racialization shape the experiences of Black women, South Asian women, and Muslim women.

We conclude that ethnic minority women often see themselves as “ticking two boxes at the same time” in terms of outcomes. However, focusing on subjective experience of all these successfully negotiated mechanisms of representation, we show that they continue to suffer a multiplicity of disadvantages, illustrating how gender and ethnic inequalities persist even for electorally successful ethnic minority women, leaving them fighting two, if not more, battles.

Intersectionality in Political Representation

Lower levels of descriptive representation and higher barriers to standing for election have been found for women (Childs and Lovenduski Reference Childs, Lovenduski, Waylen, Celis, Kantola and Weldon2013; Mackay Reference Mackay2004), ethnic minorities (Sobolewska Reference Sobolewska2013; Stegmaier et al. Reference Stegmaier, Lewis-Beck and Smets2013), working-class people (Matthews and Kerevel Reference Matthews and Kerevel2021; Murray Reference Murray2021), and candidates with disabilities (Indriyany et al. Reference Indriyany, Hikmawan and Mayrudin2019; Reher Reference Reher2022). Research on these groups’ political representation have largely developed in isolation from one another, resulting in the frequent omission of intersectional disadvantages in representation (Krook and Nugent Reference Krook and Nugent2016; Minta Reference Minta2012; Severs et al. Reference Severs, Celis and Erzeel2016). This tendency centers privileged members within groups — for example, white women within the category of women or ethnic minority men among ethnic minorities — which means that the experiences of ethnic minority women have been relatively overlooked (Reingold et al. Reference Reingold, Widner and Harmon2020, 819). Additionally, this “logic of separation” risks framing “women” and “ethnic minorities” as competitors in gaining political representation (Bassel and Emejulu Reference Bassel and Emejulu2010).

However, there is now a growing literature applying an intersectional approach that recognizes the unique location occupied by ethnic minority women. Intersectionality as a framework was born out of Black feminist critique of mainstream feminist thought and sought to redress the invisibility of Black women in feminism, drawing attention to capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy as interlocking systems of domination (for example, Collins Reference Collins1990; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989; Davis Reference Davis1981). Consequently, intersectional approaches to descriptive representation analyze how ethnicity and gender (or more social locations) interact to shape ethnic minority women’s allocation of political resources, their inclusion or exclusion from political institutions, and their experiences of serving in political office.Footnote 1

Initial studies of intersectionality in descriptive representation have been predominantly based on the US as a case study (Brown Reference Brown2014; Fraga et al. Reference Fraga, Martinez-Ebers, Lopez, Ramírez and Reingold2008; Hardy-Fanta Reference Carol, Lien, Pinderhughes and Sierra2006), but more recently have been used in European contexts and elsewhere (on Canada, see Tolley Reference Tolley2022). Europe-focused scholars have contributed additional insights not only on international variation (Celis et al Reference Celis, Erzeel, Mügge and Damstra2014; Folke et al Reference Folke, Freidenvall and Rickne2015; Siow Reference Siow2023) and challenges for women politicians associated with specific ethnicities (Dancygier Reference Dancygier2017) and within different electoral contexts (Hughes Reference Hughes2016; Ruedin Reference Ruedin2013), but also a systemization of the different mechanisms of electoral inclusion and exclusion and through which women of color can reach differential representative outcomes. In one of the most influential systemization efforts, Mugge and Erzeel (Reference Mügge and Erzeel2016) propose a framework of three distinct steps needed for electoral success and the mechanisms associated with them, which we will use to organize our own study.Footnote 2

At the first step described by Mugge and Erzeel (Reference Mügge and Erzeel2016), the mechanisms of representation are recruitment and candidate selection (Black Reference Black2002; Hughes Reference Hughes2016), networks, and targets or quotas (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Erzeel, Mügge and Damstra2014; Folke et al. Reference Folke, Freidenvall and Rickne2015; Krook and Nugent Reference Krook and Nugent2016). It is at this step, and through these mechanisms, that researchers have identified potential electoral advantages to intersectional membership of underrepresented groups (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2013; Celis and Erzeel Reference Celis and Erzeel2017). Although initially the feminist infrastructure built to increase women’s representation (such as legislative or candidate quotas, as well as specialist funding and encouragement programs) were found to be dominated by white women (Krook and Nugent Reference Krook and Nugent2016), ethnic minority women have subsequently used these quite successfully to increase their descriptive representation (Mugge et al. Reference Mügge, van der Pas and van de Wardt2019). Although this story is one of electoral advancement and increasing representation, we argue that the logic of “two boxes” and its focus on outcomes leaves out subjective experiences of ethnic minority women, where — as we will show — intersectional disadvantage is still keenly felt.Footnote 3

At the third step (see footnote one on exclusion of step two), the mechanisms of representation consist of the formal and informal rules of group representation (Mugge and Erzeel Reference Mügge and Erzeel2016). Although studying mechanisms involved in this step can focus on substantive representation (for example, Tatari and Mencutek Reference Tatari and Mencutek2015), it can also have an impact on descriptive representation by enabling and encouraging or discouraging participation in representative institutions. Gender scholars have established how the gendered foundations of political institutions and formal and informal gendered norms (Kenny Reference Kenny2014) produce distinct advantages for men. This work demonstrates how political institutions have been “created for, by and to the benefit of, the men who have, and continue to, over-populate them” (Childs Reference Childs2023, 511). There is less work on how racialization of political institutions influence representation, but even fewer studies consider intersectional institutions; these often do show that there is a palpable impact of intersectional norms on representation of ethnic minority women (Krook and Nugent Reference Krook and Nugent2016).

The research into intersectional representational outcomes is well complemented by studies of ethnic minority women’s experiences — for example, additional and crosscutting burdens of representation compared to minority men (Smooth Reference Smooth2011, 437), or increased pressure for women legislators with migrant backgrounds to take on issues of migration and integration compared to their male counterparts (Donovan Reference Donovan2012, 41). As multiply marginalized groups, Reingold et al. (Reference Reingold, Widner and Harmon2020) find that Latina legislators are active in addressing issues of concern to women and racial minorities, whereas the most likely sponsors of welfare bills are Black women lawmakers seeking “to address the needs of poor women of colour and other intersectionally disadvantaged subgroups” (829). In contrast, Murray (Reference Murray2016) shows that in secular France, there is pressure on ethnic minority women to act as “symbols of secularity and assimilation” (also see Choi Reference Choi, Poertner and Sambanis2021). Evidently, ethnic minority women can have different approaches to representation that take into account their race and gender positionality.

Drawing attention to this possible heterogeneity among ethnic minority women’s negotiating representative burdens, there is also ample literature on heterogeneity of electoral outcomes (Gershon et al. Reference Gershon, Montoya, Bejarano and Brown2019; Montoya et al. Reference Montoya, Bejarano, Brown and Gershon2022). Holman and Schneider’s research indicates that Latina women overtook Latino men in running for and gaining office, whereas Black women also exhibited higher levels of political ambition compared to Black men (Reference Holman and Schneider2018, 265; also see Bejarano Reference Bejarano2013). These conclusions overturn some assumptions about how the lack of political ambition plays a role in underrepresentation of women, which have been developed based on analyses of predominantly white women (Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2010). Finally, Dancygier (Reference Dancygier2017) observes unique challenges that hinder equal representation of Muslim women across Europe. In our study, we disaggregate by ethnicity the different experiences across multiple mechanisms of representation of ethnic minority women.

UK Local Government as a Case Study

We use local government in the UK as a case study, with a particular focus on England, as the most ethnically diverse constitutive nation of the UK. The UK is illustrative of diversity in elected bodies as it has one of the most generous electoral eligibility laws worldwide, providing most noncitizens of non-white ethnicities with immediate eligibility to vote and to stand for election for national as well as local office. This is because most people who identify as non-white ethnic minority (which is the language used in the UK’s official statistics) are migrants or descendants of migrants from Commonwealth countries in the Caribbean and Indian subcontinent (the majority of Commonwealth countries are former colonies of the British empire).

The UK is also an interesting case, as its official statistics recognize both racialized minority status as a non-white person (on a criterion of visibly different skin color) and ethnic origin simultaneously. This allows us to consider disadvantages that result from being racially minoritized in a majority white society — for example, racial abuse or harassment — as well as specific challenges resulting from prejudices against certain ethnic groups (like British Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, who are more likely to experience Islamophobia).

Although most of the existing studies into intersectional descriptive representation focus on the national level legislatures, we turn our attention to the local level. The local elected bodies, in contrast to UK Parliament, seem less dynamic in increasing representation of both women and minorities. Although local-level representation has traditionally been thought of as the easier and more accessible route for underrepresented groups to enter politics (Taagepera and Shugart Reference Taagepera and Shugart1989), recent research shows that progress at this level has largely stalled, and in some countries women’s representation is now comparable to national representation (Tolley Reference Tolley2011), whereas in others, we see a reversed pyramid of representation for women, with the national level being more representative (Fortin-Rittberger et al. Reference Fortin-Rittberger, Eder, Kroeber and Marent2019). In the UK, women’s local representation is on par with the national level (Fawcett Society 2022), but this represents slower growth over time at the local level. This is also counterintuitive, because although the majority of local government seats are allocated using a majoritarian electoral system, just like national Parliament, the districts have multiple seats, which should benefit women (Hughes Reference Hughes2016). It is likely that the relative lack of progress is a result of the lack of comparatively strong party gender quotas operating at the local level. Although the Labour party has introduced a target of 50% of their councillors being women, the quotas introduced apply to winnable or retirement wards and are applied to only one seat of the two or three seats available (Bazeley et al. Reference Bazeley, Glover, Lucas, Sloane and Trenow2017). This is unlike the All Women Shortlists for national elections, which operate in single-seat constituencies, which means that the percentage of women is able to rise more quickly. In addition, Labour has a target for all candidate shortlists to be gender-balanced. Less visible than Parliament, the kinds of pressures that parties experience at the national level to appear diverse and representative (Sobolewska Reference Sobolewska2013) are simply not present at the local level. Moreover, women’s issues tend to be marginalized in local government in the UK, which is a particularly masculinized political institution (Childs Reference Childs2023, 511).

In contrast to an almost stalling of women’s representation at the local level, ethnic minority representation has increased sharply at this level, going from 4% to 8% between 2013 and 2019, which is also on par with national level of representation (Sobolewska and Begum Reference Sobolewska and Begum2020).Footnote 4 This is despite the fact that the major parties do not have formal quotas for race at any level (Labour only has a target for one ethnic minority candidate on each shortlist at the national level). The top-line numbers belie a picture of complexity when we also account for racial background and gender. Although 34% of white councillors and 60% of Black councillors are women, we see a starker intersectional difference at the local level for South Asians, with only 31% of South Asian councillors being women (Sobolewska and Begum Reference Sobolewska and Begum2020). This is compared to 45% of South Asian MPs being women. It is therefore important that the positive story of an increasing number of ethnic minorities in local government does not disguise experiences of marginalization, particularly as the mechanisms leading to political representation still disadvantage ethnic minority women. Clearly, this difficulty also varies significantly by racial background, which we discuss in our analysis.

Methodology

Our research design was developed to study the experiences of ethnic minority local councillors from visibly racialized backgrounds of both genders, to further our understandings of the mechanisms that underpin representational inequalities.Footnote 5 We sought to sample our interviewees to reflect a range of non-white backgrounds and political experience as well as gender balance; in the end, only 40% of our interviewees were women. We conducted 94 semi-structured interviews (see Table 1), 85 of which were with British ethnic minority local councillors, and 9 with white British councillors in council leadership or cabinet positions. Five of our ethnic minority women interviewees were candidates for local council or parliament, rather than elected councillors. We also interviewed two local women activists of minority background working on political representation of ethnic minority women. In this article, we mainly use 38 interviews with ethnic minority women (and 47 ethnic minority men when they refer to relevant topics).

Table 1. Number of interviewees by ethnicity and gender

Though we collected data on gender and ethnicity of UK’s local councillors, we focused our interviews on England, which has much larger ethnic diversity. Unlike most qualitative studies of this type, however, this is not a single locality study. This allows us to generalize the experiences of women beyond a single geographical context, which excludes the possibility — present in single locality studies — that there are certain councils or places were minority women encounter a particularly positive or hostile environment, for historical, political or demographic reasons. We selected 24 local councils in England to achieve a mixture of those that have high, medium, and low ethnic minority representation, which was further stratified to achieve a mix of areas of high and low ethnic minority population density. We also included different council types: county, district, borough, and metropolitan councils, and unitary authorities, which largely correspond to levels of urbanization.Footnote 6 This diversity of localities gives us unique access to minority women who represent or seek to represent low ethnic diversity places and less urbanized locations, again in contrast to the majority of qualitative studies that usually select interviewees from large diverse cities only.Footnote 7 Some additional interviewees were added to our sample through recommendation from existing interviewees, including an ethnic minority woman councillor in Scotland and another in Wales.

Prospective participants were identified from council websites as sitting local councillors and coded as women or men and as ethnic minority or white majority through analysis of names and photos (Fawcett Society 2022). Councillors from selected councils were contacted by email to take part in an interview lasting between 45 minutes and an hour (official council emails were used). Twenty-nine interviews were conducted face-to-face in late 2019 and early 2020, but following the coronavirus outbreak and subsequent lockdowns, 65 interviews were conducted over the phone. Interviewees were asked about how they became involved in local politics, their views on the extent of demand for greater diversity in local government, and their experiences of running for selection and election for local government as well as serving as a local councillor (if applicable). Our interviewees mostly represented the Labour party, which reflects the fact that the majority of ethnic minority local councillors in the UK represent Labour (Sobolewska and Begum Reference Sobolewska and Begum2020). Our interviewees included councillors of Black African, Black Caribbean, Asian Indian, Asian Pakistani, Asian Bangladeshi, white British, and mixed or other origins, allowing us to account for heterogeneity of ethnic minority women’s experiences of political representation. All interviews were conducted by a researcher who identifies as a woman of color.

Following the interviews and transcription, we conducted an inductive thematic analysis of the interview data using Nvivo software. Themes were generated in the thematic analysis through identifying and coding patterns of shared meaning evident across interviewee responses (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2022). A sample of the interviews was coded by separate members of the research team (two women researchers of minority or migrant background and one male research assistant of minority background). We then compared and contrasted coding of interview data to determine whether data had been coded by similar themes to ensure coding reliability.

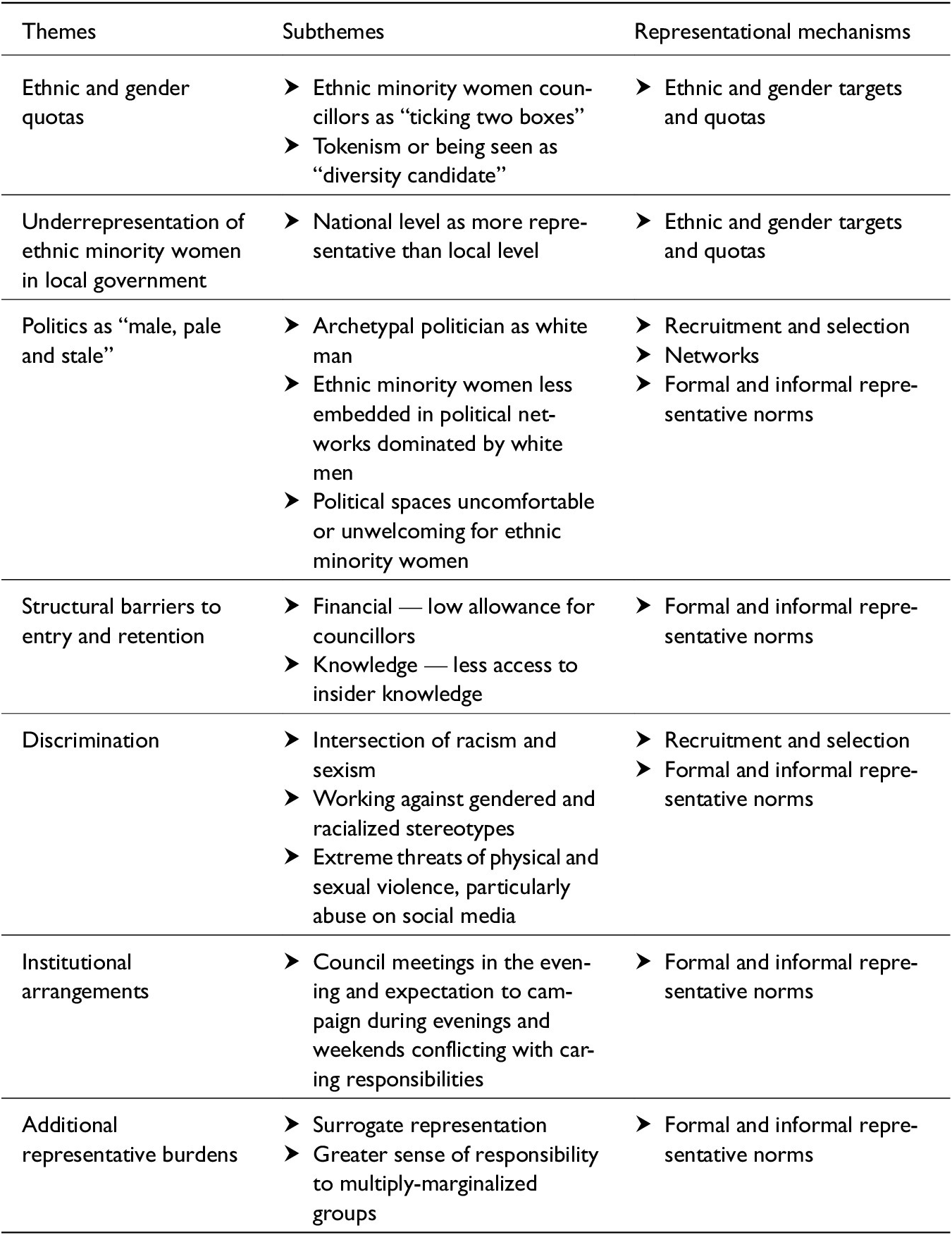

We found seven main themes and 14 subthemes related to the experiences of ethnic minority women local councillors and candidates (see Table 2). On ethnic and gender quotas, ethnic minority women felt they were perceived as simultaneously meeting targets for ethnic minority and women candidates or elected councillors, thereby “ticking two boxes” at the same time. Underrepresentation of ethnic minority women in local government as compared to the national level was a recurring theme, as was perceptions of politics as dominated by older white men. We also found ethnic minority women experienced structural barriers and gendered racism. Institutional arrangements of local councils, including evening meetings, conflicted with caring responsibilities, which can be greater for ethnic minority women. They also tended to have additional representative burdens as “surrogate representatives” for ethnic minority residents outside the ward they represented, and due to a keen awareness of intersectional disadvantages on account of their own multiple marginalization as ethnic minority women. These themes crosscut the representational mechanisms that we use to organize our discussion below.

Table 2. Overview of themes from the inductive thematic analysis

Ethnic Minority Women’s Experiences of the Mechanisms of Representation

Political Recruitment and Selection Processes

The first mechanism recognized by Mugge and Erzeel (Reference Mügge and Erzeel2016) that shapes the representational outcomes of ethnic minority women is recruitment and selection. Looking at the subjective experiences of the women, we found that this mechanism was most frequently mentioned as an obstacle and as something that is distinctively experienced by women of color. Most ethnic minority interviewees felt ethnic diversity was lacking among councillors and council staff and in cabinet and leadership positions (bar a few exceptions where there was very high visible ethnic minority presence on council, usually in highly diverse cities). Ethnic minority women interviewees raised the relative underrepresentation of ethnic minority women in local government compared to the national level.

Although most interviewees recognized efforts to increase numbers of women and ethnic minorities in Parliament, they noted that local government was lagging behind. This was explicitly linked to the low presence of women in local government as a whole, which they thought made it even more difficult for ethnic minority women. One British Pakistani woman local councillor remarked that “local government don’t really like women in politics anyway”, before adding that “Asian women really struggle” (F10). Perceptions of politics, particularly at the local level, as being dominated by older white men was widespread, with interviewees expressing concerns about not being seen as “fitting in”: “I never wanted to come into politics, I didn’t think it was a place for me, I thought it was something for white middle-class men, middle aged men, didn’t really think it was a place for an Asian woman” (F19A_British Asian Pakistani Woman councillor).

Thus, associating politics with the archetypal “male, pale and stale” politician (Thrasher et al. Reference Thrasher, Borisyuk, Rallings and Shears2013) was potentially off-putting, especially for ethnic minority women, who do not fit this mold. This is consistent with Puwar’s work on women and ethnic minorities as “space invaders” who feel out of place in political office due to “the white male body [being] taken to be the somatic norm within positions of leadership and the imagination of authority” (Reference Puwar2004, 67). A woman activist of Black African background identified this as a self-perpetuating problem: “You can’t be what you can’t see… if you don’t see many people standing for election that look like you, then they’re just going to think well that’s not a place for you to be, so you’re not going to want to stand for election” (F27_ British Black African Woman activist).

Our interviewees frequently mentioned that party recruiters tended to leave out ethnic minority women, as their approach to recruiting in South Asian communities focused exclusively on men. Consulting male “community leaders” has often marginalized the voices of South Asian women (Takhar Reference Takhar2014, 3), and the parties leveraging these patriarchal traditional structures to encourage candidates for office marginalizes women’s presence in politics (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Sobolewska, Wilks-Heeg and Borkowska2017). Our interviewees reported that where party selectors seek to recruit in areas of high Pakistani population, for instance, they look to male candidates. Male candidates have generally been seen by parties as able to tap into patriarchal “biraderi” or kinship networks (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Sobolewska, Wilks-Heeg and Borkowska2017) when campaigning for ethnic minority votes (Hussain Reference Hussain2021). For example, party recruitment through mosques decreases the chances of reaching Muslim women, since mosques are predominantly attended by men:

Traditionally, the likes of the Labour Party has vied for the ethnic vote and usually, they’ve only gone to the men. So, working class people of colour, particularly South Asian, it’s usually the men who have been having contact and dialogue with the city councillors, and the councillors, and the MPs, it’s not the women. And that’s patriarchy structured. (F12_British Asian Pakistani Woman councillor)

The increased difficulty in access as both a woman and of minority background was widespread among our interviewees: I always say to white women, that “yeah, you have glass ceilings, but other women, Black women, in particular, have reinforced concrete ceilings. So, our ceilings are not the same” (F12_ British Pakistani Woman councillor).

Targets and Quotas

Another mechanism that was mentioned frequently in our interviews was party diversity targets and quotas. Something that was especially visible was the sense of competition between gender and racial targets. Even if the literature on outcomes finds that this may no longer affect outcomes, it still strongly structures the experience of minority women. Many of our interviewees noted that ethnic diversity was seen as desirable for political parties, but mostly through the lens of “ticking boxes” or filling an ethnic quota or target. Visible diversity often means that parties can improve their public image by presenting themselves as modern and inclusive (Sobolewska Reference Sobolewska2013). Since both gender diversity and ethnic diversity can be some of the most visible types of diversity, increasingly ethnic minority women are given priority in selection processes over ethnic minority men “since they are members of two key categories that political parties want to promote” (Freidenvall Reference Freidenvall2016, 358), thus filling spaces more effectively (Celis and Erzeel Reference Celis and Erzeel2017). This pattern has been observed by a few of our interviewees: “seven councillors, seven cabinet members and only one of them is a BME woman, so BME or a woman, this time it’s the same person happen to tick both boxes for them” (M10A_British Asian Pakistani Male local councillor).

Ethnic minority women can be desirable candidates as a result of being viewed as more electorally appealing and less of a threat to the institution compared to ethnic minority men (Freidenvall Reference Freidenvall2016; Severs et al. Reference Severs, Celis and Erzeel2016, 349–50). Ethnic minority women who appear assimilated — for example, young, well-educated women — can be seen as more “acceptably different” (Durose et al. Reference Durose, Richardson, Combs, Eason and Gains2013), as they are perceived to further progressive gender norms, whereas negative stereotypes about minority men means that they are perceived to be tied to traditional gender roles and be more sexist (Freidenvall Reference Freidenvall2016, 358). This potential advantage, which can ease access to elected office can, however, present a double-edged sword for ethnic minority women who are set up in competition, not only with white men (who dominate local government) and white women but also with ethnic minority men. Our interviewees noted this issue and also worried what it meant for how they might be perceived by their fellow councillors. For example, there were concerns that they may potentially be perceived as having achieved their position not on their own merit, or even because of being an ethnic minority or a woman, but due to being both. Although it might seem like a useful fast track to local government for underrepresented groups, it also introduces psychological self-doubt:

I’ve been [recently] elected and I’m already in the cabinet, so that’s great but I suppose there’s a little bit of self-doubt as well that I think, you know, some of my colleagues who’ve been elected for like 10, 15 years thinking, “she’s doing it, they’re just doing it because she’s an Asian woman.” Is it tokenism? Does she, has she deserved that position or not? (F24_British South Asian Woman councillorFootnote 8)

Thus, they were aware of criticisms that attempts to increase diversity can be seen as undermining “meritocracy” and can lead to a backlash (Puwar Reference Puwar2004, 72). Thinking of ethnic minority women’s progress as tokenism comes with the implication that the “natural” order of the institution — that is, of white male dominance — is one of meritocracy, and that less “qualified” candidates are being chosen due to their gender or ethnic background (or both). This reinforces white male institutions as being disrupted by perceived outsiders through enforced quotas.

Networks

Political networks, another of the crucial representational mechanisms identified by Mugge and Erzeel (Reference Mügge and Erzeel2016), were so dominated by white men that being the only ethnic minority person attending local party meetings — and feeling unwelcome — was commonly reported. Men also spoke of their lack of networks: “Because the ethnic minorities have got to almost create their own platform, their own environment, their own network and their own channels to get through” (M15C_ British Bangladeshi male councillor). However, this issue was mentioned more in our interviews with women. For one woman councillor of Black African background, ethnic minority candidates were “competing against people that are very embedded in the culture, very embedded with the connections and it is predominantly white people” (F19). Similarly, another ethnic minority woman councillor of Pakistani background felt meritocracy was a myth:

What you understand as a marginalised person, entering a very white male and white women dominated arena, there is absolutely no level playing field. You could be the best candidate in the world but if you’re not part of their structures and you haven’t … ever been part of their structures, it’s very hard to get ahead [or] get elected. … It’s about how much time you spend lurking around in this very white … often hostile spaces to minorities. (F12_ British Asian Pakistani Woman councillor)

In this way, the white male–dominated political networks were seen as a barrier, especially for ethnic minority women. When recruiting for political office, parties will often look to individuals already embedded in their networks (Silva and Skulley Reference Silva and Skulley2019, 345), and particularly those individuals who reflect their own characteristics, that of the “archetypal” white male politician (Durose et al. Reference Durose, Richardson, Combs, Eason and Gains2013, 247). A male councillor of Pakistani background recalled a case where an inexperienced younger white man was selected as a candidate over a white woman who was more established in the community and an Asian man who had decades of experience in local government: “But no, they picked the nice pretty young white boy” (M10_ British Asian Pakistani male councillor). Thus, a white masculine norm is perpetuated in these political institutions, where white men are viewed as more suitable for political candidacy and office.

Even in areas where membership of local parties was predominantly of ethnic minority background, interviewees felt that those engaged in shortlisting and selection processes were still predominantly white. Events and schemes on “how to become a councillor” (especially those targeted toward women and ethnic minorities) were seen as particularly useful, but there were informal forms of knowledge, for example, on the internal politics of local party branches that were inaccessible for outsiders. Our interviewees thought that informal knowledge and insider expertise that were important to being selected were not in the public domain with one woman councillor of South Asian background believing that knowing people within the white male–dominated political networks was important to accessing information to “unlock the mystery of how these processes work”, and that “perhaps you’re less likely to know people if you’re from certain [ethnic] backgrounds” (F29B). In this way, ethnic minority candidates felt disadvantaged in the selection process. For example, a woman councillor of Black Caribbean background referred to “weird trick questions” being asked by selection panels and the importance of being coached to know what to say during party selections (F13). Another interviewee believed that ethnic minority candidates who were embedded in their local community and understood local issues better were being passed over for candidates who were more embedded in the white political networks and thus coached in this way:

We need to change how we interview people to stand for councils…. A lot of ethnic minorities were very embedded in their local community. … They understood the issues locally, on the ground. But when it came to answering the political question, like, what is the role of whip … would you vote for an illegal budget? They weren’t able to answer those political questions, and that was because they weren’t part of the political kind of elite…. But I knew they would be really good councillors because they understood their communities more than some of those people that were part of the political elite who just had these polished answers. (F19_British Black African woman councillor)

The theme of opaque selection interviewees appeared often, with institutional norms being differentially applied without sanction. The exclusive nature of existing political networks and uneven access to institutional knowledge was reinforced by the selection process, which did not have any outside scrutiny. Another example was given by a candidate who was told by a colleague that she was asked different questions from the white candidates by the same selection panel:

She said, “you were asked 13 questions, the other candidates weren’t even asked anything close to that, and some of the questions asked wasn’t even relevant,” now I would never have known that, I just thought that that was normal, but she said “it’s not normal at all, it’s extremely racist.” (F03_ Black Caribbean woman candidate)

Difficulties in joining and operating insider networks were even harder for some ethnic minority women; particularly intersections with religion add further levels of disadvantage. Many of our Muslim interviewees felt social events in the council were geared toward drinking and meeting in pubs where they felt less welcome or were not comfortable joining. Networking and even decision-making often takes place in drinking establishments and spaces where observant Muslims would be less likely to enter (Durose et al. Reference Durose, Richardson, Combs, Eason and Gains2013, 247). One Muslim woman councillor of South Asian background who pushed for events not to be held in pubs felt resentment: “You [become] that awkward lady in the headscarf who doesn’t drink, who’s made us have fundraisers without alcohol” (F24). Although also an issue for Muslim men, visibly Muslim women can feel particularly out of place in drinking establishments. There can also be a stigma attached to Muslims going into pubs, and even more so for Muslim women. Similarly, a woman councillor whom we describe as of “Other”Footnote 9 minority background felt there was discomfort around her as someone who does not drink alcohol or socialize in pubs compared to someone who does and whom they would be able to get to know better: “It’s about familiarity for a lot of them, it’s about, ‘Oh, yeah, this person is like us.’ So, it didn’t matter the fact that you might be the better candidate. The fact that they socialise with this person … because that’s how they know [them] … that’s how people tend to pick” (F20_woman councillor of Other ethnic minority background). Religious and other sources of heterogeneity among ethnic minority women were believed to be far from recognized by local government in their approaches to diversity.

Informal and Formal Representative Norms

The last representative mechanism that affects ethnic minority women’s electoral outcomes according to Mugge and Erzeel (Reference Mügge and Erzeel2016) are the institutions of representation themselves, and the kinds of formal rules and ways of working, as well as informal norms by which they operate. Since parliamentary institutions, also at the local level, were designed for men and by men, the work within these institutions is likely to discourage women from participating, thus affecting their representative outcomes. We can extend this logic to also argue that these institutions have also been created by white men for white men; however, instead of outcomes, we focus on the more detailed picture of what ethnic minority women find when working in these institutions. Because much of our interview material pertains to this experience, we subdivided it further to examine experiences of direct discrimination, institutional obstacles, and the extra workload created by representational pressures on ethnic minority women.

Direct Discrimination

Experiences of discrimination against ethnic minority women local councillors can be understood through norms in political institutions and power being associated with the white male body, and these discriminatory institutional norms appeared frequently in our interviews. Ethnic minority male councillors also reported racism — for example, a British Indian male councillor we interviewed recounted an incident of overhearing a councillor from another party refer to him using the P*ki racial slur (M19).Footnote 10 However, for our ethnic minority woman participants, reports of experiencing sexism in the male-dominated culture of local government, and especially racialized sexism, dominated: “There’s a lot of misogyny for instance in the council and a lot of them think that it’s a bit of a laugh to tell women that you know, there’s so many women now…. I was told, ‘Why isn’t the male councillors’ shirts being ironed?’” (F20_Woman councillor of Other background).

Another woman councillor of Pakistani background described “constant exclusion” within the council and deliberately being given the wrong times by her male colleagues so that she would miss council meetings (F26B). South Asian woman interviewees described forms of sexism they experienced in their own community from some men who opposed their position and visibility in public life, but they also recounted gendered racism from white men they serve alongside as councillors — for example, being asked if they were “allowed” to be a councillor by their husbands:

So the BAMEFootnote 11 women get blocked from the BAME men, they get the blockage issues from the white men and to be honest the other general [white] women, equality is always fine as long as it’s white women. It’s just the culture, the attitude that women obviously are supposedly inferior, you get the bigotry from the white women, it’s one way of keeping away the competition. You’ve got the white males and you’ve got the Asian and BAME males as well. (F26_British Asian Pakistani Woman local councillor)

Though more greatly experienced by Black women, the stereotype of the “strong woman of color” and exclusion from these racialized and gendered forms of womanhood was also evident in the experience of a woman councillor of Pakistani background who recalled being up for a position against a white woman candidate who was unable to perform in the process but was still chosen for the position over the ethnic minority woman applicant: “She didn’t answer her Q&A, she burst into tears, you know, there was no way she knew enough about the subject but she got the position, so that does happen” (F26_Interview with British Pakistani woman councillor). With associations of white femininity with normative womanhood, white women are more likely to be afforded emotional support due to gendered notions of fragility and emotional vulnerability, whereas ethnic minority women — particularly Black women — are often subject to harsher treatment.

Heterogeneity: Black Women

Experiences of gendered racism differed by racial background. Black women councillors, for example, described being mistaken as a member of the cleaning staff, or there were assumptions that the man accompanying them was the councillor. This has also been experienced by Black women members of Parliament, including Dawn Butler, who was mistaken for a cleaner in Westminster by a fellow MP.Footnote 12 As authority is associated with white male bodies, ethnic minority women are imagined to occupy more junior positions rather than positions of leadership (Puwar Reference Puwar2004). As Puwar writes, “this clearly shows how people are reluctant to bestow authority on specific types of racialised and gendered bodies … especially when women are young, and they are assumed to be assistants or helpers rather than central figures of authority and command” (Puwar Reference Puwar2004, 73).

Multiple Black women interviewees recalled not being called by their name, with one British Black African woman councillor describing an older white male colleague repeatedly calling her “babe,” “girl,” or “sweetheart,” whereas another British Black Caribbean woman councillor recalled a white man who would refer to her as “Bob Marley’s sister” (F08). One of them said the following, recalling a recurring theme of local government lagging behind national politics:

In local government, I think they really don’t make that much effort to try and hide their racism and biases. For example, … white members or white councillors would just call all three of the Black women one of the Black women’s names, every time they saw them. … It’s that lack of — I don’t know, common decency to learn the names of three distinguished black women and call them by their rightful name. (F27A_ British Black African woman activist)

Although the sense here is that it would not happen at the national level, Palmer’s (Reference Palmer2019) analysis of “misogynoir,” or the ways in which racism and anti-Blackness alter the experiences of misogyny in the case of Dianne Abbott MP, demonstrates the distinctive forms of gendered and sexualized racism that Black women politicians face. Gendered anti-Blackness underlies the intersection of sexist and racist abuse directed at Black women in politics, and the exclusion of Black women from “womanhood” as racialized and gendered notions of white femininity are positioned as the norm (Palmer Reference Palmer2019, 512). Gendered treatment of caring and understanding toward women is afforded to white women, whereas the stereotype of the “strong Black woman” persists — for example, the “implicit expulsion of Abbott from a category of protected and defensible womanhood” when she slipped up in a televised interview (Palmer Reference Palmer2019, 511).

Moreover, ethnic minority women politicians, especially Black women, have been subject to extreme threats of physical and sexual violence, particularly on social media. Although a few male interviewees did mention racist abuse, including death threats, the topic came up in multiple interviews with women. We know all women politicians experience this more than men (Collignon et al. Reference Collignon, Campbell and Rüdig2022); however, this is compounded by gendered racism for ethnic minority women (Palmer Reference Palmer2019, 510). Compared to racist abuse toward ethnic minority male councillors, which was not explicitly gendered, the threat of sexual violence against ethnic minority women was significantly more pronounced. Being targeted for abuse was perceived by our interviewees as putting off other ethnic minority women from coming forward for political office. One councillor described being smeared as promiscuous — for example, having pictures posted through her letter box of her face photoshopped onto a naked body (F10). Experiences of harassment were felt to be common among ethnic minority women, and particularly Black women, who recalled being compared to animals in abusive social media posts. One British Black Caribbean woman councillor explained how threats of violence on social media had led her and another Black council member to put CCTV (surveillance cameras) in their houses (F29). Another interviewee explicitly defines her experience as unique to her as a woman and a minority person, making her a “target”:

Especially if you’re a woman … that’s the thing that I’m considering about do I want to, if I get asked again, do I want to do this, considering the times that we’re living in? And I’m the woman that lives alone. Because I did face some, you know, some racism and catcalling and stuff. … Having your face on a poster … is making yourself a target. … I don’t think non-ethnic [minority] candidates have to think about that, that they could be a target. But the violence, this is a major barrier I feel. (F13_British Black Caribbean woman councillor)

Heterogeneity: South Asian and Muslim Women

For women of South Asian origin, assumptions about cultural gender norms sometimes clashed with institutional norms of political campaigning, including campaigning in the evening. One British Asian Pakistani woman referred to a “stigma attached to Asian women knocking on strangers’ doors” (F10). Concerns about public visibility and entering a male domain considered inappropriate for women (Takhar Reference Takhar2014, 7) were shared by a woman councillor of Pakistani background, particularly as a young, unmarried woman, whereas another South Asian woman councillor of Indian background described being conscious of “walking the streets with a white guy” and being “talked about” if she were seen with different male colleagues while out canvassing in the evenings after dark (F03B). In this way, some of the South Asian woman interviewees were concerned about the reputational consequences of being perceived by more traditional members of their community as promiscuous or having relationships before marriage. However, the latter interviewees referred to a mixture of sentiment in their local community as young South Asian women standing to be councillors — with some community members disapproving, whereas others were more encouraging of them for representing their community interests.

Interviewees felt South Asian women were often stereotyped as submissive and oppressed in white council spaces. A Muslim woman councillor of Pakistani background who wore a hijabFootnote 13 received comments that she needed to be “more modernised” and that she was not “westernised enough” (F24A). In this way, religious dress worn by Muslim women politicians meant that they were perceived not to be suitably assimilated into British society and that this marked out their “otherness.” For Choi et al. (Reference Choi, Poertner and Sambanis2021), discrimination against Muslim women is shaped by stereotypes that Muslims, particularly women who wear a hijab, hold conservative attitudes about women’s rights, but there is less discrimination toward Muslim women who are perceived to hold progressive gender attitudes (Choi et al. Reference Choi, Poertner and Sambanis2021).

Some Muslim women described how they were often working against ingrained stereotypes of how a Muslim woman would behave. One British Asian Pakistani Woman councillor recalled her experiences of gendered Islamophobia, including from a white male journalist who had remarked derisively that she was “very confident” as well as a more senior white woman in local government being disrespectful and patronizing toward her as a visibly Muslim woman (F12). Similarly, a British Pakistani male councillor referred to stereotypes of Muslim women as being “oppressed”:

Some of the attitudes that are if a woman walks into a room and she’s got a headscarf on, she’s either oppressed or she’s been forced to put the headscarf on. That’s sometimes really annoying. One of my daughter’s wears a headscarf and the other one doesn’t. I said, ‘It’s your choice, I’ll never tell you what to wear.’ That’s what most white people in the Labour party would say to their own children. … It’s quite patronising really for the women. (M27C_British Pakistani male councillor)

Institutional Obstacles

Costs

Although political parties are important to providing resources such as printing costs for flyers and leafleting in campaigns, most of our interviewees described the significant financial barriers and often hidden costs to running for election and serving as a councillor. An informal norm to emerge in our interviews was that most participants held a full-time job to support themselves alongside serving as a councillor. The relatively low allowance for councillors, which many of our participants did not consider a liveable wage, meant that, unless retired, councillors had other careers as well. Although some men did mention costs, these were usually not perceived as major obstacles: “I’d say there is definitely a time cost rather than a financial one … for at least, local government (M22_Black Male councillor).

Financial barriers were more keenly felt by women, and particularly ethnic minority women, as the issue of cost interacted with issues of safety and increased caring responsibilities. Being able to afford a car, for example, meant “it’s not dangerous for [men] to be walking [alone] at night” (F13_Black Caribbean woman councillor) as it would be for women. Given that we already illustrated our interviewees already felt their safety was more threatened as ethnic minority women than it would be for white women, this issue is a good illustration of compounded disadvantage.

Additionally, our interviewees keenly perceived their experience here as shaped more than by gender and race and commented on how these sources of marginalization interacted with class status. One interviewee drew attention to how the costs of being involved in local politics is experienced in differential ways:

If you’re from an Indian or a Chinese background, you might have a very different socio-economic experience in the UK compared to a Pakistani or Bengali … resident who is much more likely to be in poor housing, poor employment, poor education access…. And all of that under-representation follows, right? … And most women in those communities wouldn’t be economically active…. Those are compounded for individual ethnic groups. If you are disproportionately affected by poverty … your capacity to be involved, to have the … the space to even … the luxury to even think about how society could be better and how you could play a role in that you know, is not equal amongst us.” (F29B_ British South Asian Woman local councillor)

Thus, although the relatively low allowance for councillors was mentioned by many of the ethnic minority male participants, ethnic minority women councillors also raised the issue of ethnic minority women being more economically marginalized and thus less able to potentially take on the role of councillor.

Time and Caring Responsibilities

With local councils as masculinized institutions established by men, another institutional norm was the timing of council meetings during evenings — timing which is not conducive to family life and proves to be a greater demand for women of their time and resources due to gendered expectations of caring responsibilities (Bernhard et al. Reference Bernhard, Shames and Teele2021). Though a few of our ethnic minority male participants referred to caring responsibilities conflicting with the requirements of serving as a councillor, this was raised significantly more by the ethnic minority women interviewees. The pressures of caring responsibilities on women politicians are well documented — for example, women deciding to delay their political careers until their children are older and more independent (Silva and Skulley Reference Silva and Skulley2019; Takhar Reference Takhar2014). However, ethnic minority women tend to have even greater caring responsibilities, including toward extended family, older relatives in multigenerational households, in-laws, and the wider community in which they are embedded. Ethnic minority women “[facing] more intense familial obligations” and covering additional household duties outside of employment are made more difficult by having less access to financial resources to cover these second-shift obligations (Holman and Schneider Reference Holman and Schneider2018, 266):

I know among Asian women, they take on a lot of family responsibilities. So, in addition to working they are also taking care of their family and extended family. It might be their in-laws or their older parents and stuff like that. … So, in that respect I think women, ethnic women do face a bit of difficulty. So, people will say, “Oh well you come home at 17:00 so why can’t you come to a meeting at 19:00”? It’s not that straightforward, there are many other things that an ethnic minority woman may have to do that someone who is not from an ethnic background would not have to do. (F02_Woman councillor of South Asian background)

These expectations of increased caring responsibilities could then be weaponized against minority woman candidates by selectorates and by other councillors when they are in office. This was particularly the case for ethnic minority women due to perceptions of ethnic minority communities being more patriarchal. This meant that they were held back by gendered racist stereotypes: I had comments like, “Well you’re a mother and you’re working, we’re going to lose this election because of you” (F20C_British Indian woman councillor). Similarly, an activist from a white British background who campaigned for greater ethnic minority and gender representation felt that the clash between caring responsibilities and institutional arrangements could be used against ethnic minority women:

There’s always been questions about “are you going to be able to come to meetings, won’t you have to look after the children and be at home?” and that’s even more of an expectation on women from ethnic minorities than it is for white women. (F10A_White British woman activist)

Increased Workloads

Another type of representative norm that affects minority women is the kind of representative burdens they are expected to carry (Murray Reference Murray2016). What we found is that our interviewees frequently felt pressures for additional labor expected of them once in office — for example, being approached for help from ethnic minority residents from outside their ward:

Q: So, why do you think they’re approaching you rather than their own councillor in their ward? It’s happening from … leaders within their own communities, they’ve heard about me, they know that I’m a woman or … you know … but it’s … it’s through recommendation from other councillors and other people that have seen … how I operate. (F05_British Asian Pakistani Woman local councillor)

This is a classic example of how Mansbridge describes surrogate representation: “representation by a representative with whom one has no electoral connection — that is, a representative in another district” (Reference Mansbridge2003, 522). Although this had positive effects on ethnic minority residents who feel better represented, it added to the workload of ethnic minority women councillors as they took on supporting residents from outside their ward.

Similarly to when they spoke about the costs of being a councillor, ethnic minority women councillors were conscious of multiple and intersecting inequalities and felt a greater sense of representational responsibility (which we did not find among our ethnic minority male interviewees):

As far as I can see everything is connected…. So, we’re talking about austerity, the living wage…. I work with women experiencing rough sleeping and homelessness…. For me, all of these areas intersect so inequality drives racism, it drives bigotry … it drives inadequate housing policies which then lead onto more women being impacted because they’re more vulnerable to inequalities, so, it all feeds in.” (F05_British Asian Pakistani Woman local councillor)

This is consistent with Reingold et al. (Reference Reingold, Widner and Harmon2020), who find that the identities and perspectives of ethnic minority women, which are shaped by intersectional experiences of racism, sexism, and economic deprivation, “enable and empower them to advocate on behalf of [the] ‘intersectionally marginalized’” (820). This sense of additional responsibility among ethnic minority women toward multiply-marginalized groups, however, increased their workload for our interviewees — from assisting minority women outside of the local ward they represented to tackling multiple intersectional disadvantages in their work as a councillor. Given the already higher obstacles to becoming a councillor, and the costs and more negative experiences of serving as a councillor, accounting for additional burdens adds to the picture of minority women councillors fighting two, if not more, battles.

Discussion and Conclusion

Unlike much of the existing intersectional research on descriptive political representation, which primarily emphasizes the outcomes, such as becoming a candidate or an elected representative, we focus our contribution on the subjective experiences of ethnic minority women in negotiating different stages of the process of becoming representatives. We argue that looking at the relative electoral progress can obscure how difficult negotiating different mechanisms leading to such progress can be for ethnic minority women. We add to the growing literature that shows a nuanced picture of representative success, by breaking down the path toward this success into distinct stages and mechanisms, following Mugge and Erzeel (Reference Mügge and Erzeel2016), and by investigating how intersectional (dis)advantages shape minority women’s experience of representation. We conducted qualitative interviews with ethnic minority local councillors in the UK and analyzed their experience at each stage. In this article, we predominantly use interviews with women, although we also use interviews with men to demonstrate distinctive intersections in the experiences of ethnic minority women representatives. We found that at most of these steps, ethnic minority women report tackling additional difficulty, discrimination, and burdens, even if their multiple identities also mean that they experience some advantages through the initial recruitment and selection mechanisms.

At the first step toward representation, Mugge and Erzeel (Reference Mügge and Erzeel2016) distinguish the mechanisms of recruitment and selection, quotas, and networks. Analyzing each in turn, we found that ethnic minority women appreciated that they may be more desirable candidates for political parties as they meet ethnic and gender quotas simultaneously. This pattern of “ticking two boxes” has been shown to be prevalent in proportional systems, but it clearly also operates in the majoritarian local government too. However, our interviewees felt that fewer ethnic minority women candidates come forward due to the limited visibility of ethnic minority women in local government, creating a vicious cycle of underrepresentation. Our interviewees reported that it is white male candidates, who reflect the characteristics of the archetypal politician and are more likely to be embedded in existing political networks, that tend to be recruited (Puwar Reference Puwar2004; Thrasher et al. Reference Thrasher, Borisyuk, Rallings and Shears2013). Even once elected councillor, ethnic minority women also felt they did not “fit in” into these networks — for example, work-related and social activities around drinking alcohol are less accessible particularly for Muslim women.

At the next step of representation, focused on representative institutions themselves, we looked at how institutional norms and rules shaped the experiences of ethnic minority councillors. Our interviewees outlined the many forms of sexism and gendered racism that they experienced from the public and their fellow councillors, as well as indirect discrimination due to existing institutional setups. On the first point, we discovered that lack of respect within councils as well as abuse and threats of violence from the public toward ethnic minority women representatives were all mentioned with alarming frequency. On the second point, we found that many institutional arrangements reinforced structural barriers. Although our men interviewees also mentioned financial costs as an issue, for women this was an issue mentioned much more frequently and at length. Other arrangements often mentioned included the timings of council meetings, which were particularly critical for minority women who tend to have even greater caring responsibilities than white women.

At the final stage of the representative process, we found that ethnic minority women politicians experienced additional and crosscutting burdens of representation compared to white women and ethnic minority men (Donovan Reference Donovan2012; Reingold et al. Reference Reingold, Widner and Harmon2020; Smooth Reference Smooth2011). Due to their own experiences of marginalization, minority women frequently felt a greater responsibility toward multiply-disadvantaged groups, including acting as “surrogate representatives” to ethnic minority constituents outside the ward they represented, all adding up to greater workloads.

Throughout, we draw attention to heterogeneity among ethnic minority women. We found that at almost all of the different stages, the experiences of women differed by racial background and other intersectional influences, including class. However, these differences were starkest when it came to forms of gendered racism. Black women were often not recognized as councillors and were assumed to occupy more junior positions. As well as Black women being rejected as figures of political authority (Puwar Reference Puwar2004), they face extreme threats of physical and sexual violence, particularly on social media. Meanwhile, South Asian women, and particularly hijab-wearing visibly Muslim women, experienced being talked down to or patronized due to gendered and racialized stereotypes of them as submissive and oppressed (Choi et al. Reference Choi, Poertner and Sambanis2021).

Another contribution of our article is our focus on local government, which is less well researched, despite for many politicians being the entry point for their careers. At the local level, political parties experience less media and public scrutiny than they do at the national level, which leads to relative obscurity for the power brokers who select candidates as well as dominate and run representative institutions. Our interviewees felt they were more marginalized in local government compared to the national level. Moreover, many minority women reported that rather than recognizing some of the institutional barriers to ease them, their colleagues sometimes used these disadvantages to discourage them and hold them back. The sense that at the local level desirable norms of anti-racism and anti-sexism were weaker was palpable. More attention to this level of government is needed to ensure that similar enforcement of equality policies applies here as at the national level. This is especially the case when relative representative success can be used to obscure some of the problems ethnic minority women still experience. Though now being elected in greater numbers, and sometimes even preferred over their male peers as they “tick two boxes,” they still encounter multiple obstacles and prejudices and continue to fight on multiple fronts.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and helpful comments. We also thank Dr. Fernan Osorno Hernandez for his research support in coding the interviews and Dr. Ceri Fowler for her comments on an early draft. Thanks also to Professor Bridget Byrne and colleagues in the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity at the University of Manchester for their support.

Funding statement

This project on ethnic diversity in local government has been co-funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number ES/R009341/1) and School of Social Sciences, University of Manchester.