Introduction

In their study of the impact of partisan political polarization and violence in the United States, Kalmoe and Mason (Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022b) made an arresting, though ancillary, finding: individuals who exhibit hostile sexism are statistically more likely to express support for partisan political violence. Hostile sexism is an overtly misogynistic type of sexism, frequently directed against women who fail to conform to traditional gender norms, in which women are depicted as manipulative and seeking to gain power over men, and gender equality is viewed as detrimental to masculinity and traditional cultural values (see Glick and Fiske Reference Glick and Fiske2001).Footnote 1 Kalmoe and Mason (Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022b) found the relationship between hostile sexism and support for partisan political violence to be strong and highly robust. Indeed, they found that the effect of hostile sexism on support for partisan violence rivaled that of trait aggression, the propensity of subjects to have an aggressive or pro-violence personality. Kalmoe and Mason provided little discussion of this surprisingly strong finding. They explained that hostile sexism is associated with increased tolerance of interpersonal and intimate partner violence, but offered no real explanation for why hostile sexists would be more likely to view political violence — specifically violence arising from partisan polarization or conflict — to be acceptable.

Aside from the Kalmoe and Mason study, the relationship between sexism and attitudes toward political violence or violent extremism among Americans has not been directly explored. Other attitudes that are related to — and potentially covary with — sexism have been identified as predictors of support for political violence in US public opinion research. For example, scholars have found that subjects exhibiting racial resentments and aversion toward minorities and other social outgroups are more likely to support political violence (Armaly and Enders Reference Armaly and Enders2022; Piazza and Van Doren Reference Piazza and Van Doren2023). Other studies find that subjects oriented toward discriminatory cultural traditionalism and attendant ideologies, such as Christian nationalism, are more supportive of political violence (Armaly, Buckley, and Enders Reference Armaly, Buckley and Enders2022). Moreover, subjects who fear social changes involving, among other things, the empowerment of previously marginalized social groups express greater levels of support for political violence (Piazza Reference Piazza2023b). However, none of these studies explicitly studied sexism or misogyny.

Examining public opinion outside of the United States, scholars have found that subjects in Muslim majority countries who proscribe highly traditional and restrictive gender roles for women — for example, arguing that they should be compelled to veil and should not work outside of the home — are also more likely to view terrorism, a form of political violence, as justifiable (Cherney and Povey Reference Cherney and Povey2013). The authors explain this finding by noting that subjects holding this attitude are potentially influenced by more rigid and uncompromising interpretations of Islam. Survey research conducted in Thailand, Bangladesh, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Libya finds that individuals expressing hostile attitudes toward women and the notion of gender equality are more prone to violent extremist viewpoints, more likely to support violent extremist actors, and more frequently report having engaged in actual violent extremism (Bjarnegård, Melander, and True Reference Bjarnegård, Melander and True2020). Like Kalmoe and Mason, the authors find sexist attitudes — specifically, opposition to gender equality — to be a highly substantive predictor of violent extremism compared with other factors. The authors argue that sexist ideals of dominant masculinity and subordinate femininity explain their findings, but provide no empirical test of this contention. Other work finds gender inequality in countries, writ large, to be a contributor to violent conflicts within societies (see survey of literature by McDermott Reference McDermott2020). However this body of literature adopts a macro-sociological/political approach and does not offer an explanation for why sexist individuals express greater support for political violence.

A very robust and growing body of research examines violence against women engaged in politics. This work documents and analyzes the rising trend of violent backlash — manifested as threats, harassment, semiotic violence, and physical violence — in the United States and globally against female politicians and candidates, and against the political empowerment of women in general. Scholars writing in this genre explain that such violence is motivated by strong misogynistic resentments against women who do not conform to traditional (disempowered and subordinated) gender roles and statuses within the social hierarchy (see, for example, Bjarnegård, Melander, and True Reference Bjarnegård, Melander and True2020; Krook Reference Krook2020, Reference Krook2022; Raney Reference Raney2023; Sanín Reference Sanín2020; Wineinger Reference Wineinger2023).Footnote 2 This literature focuses mostly on threats or acts of violence against women, and their attendant patterns and predictors, rather than the connection between sexist attitudes and tolerance or support for political violence within the American public, as measured through public opinion. However, this research is crucial because it provides theoretical support for our study and demonstrates that misogyny has the potential to manifest in episodes of real-world violence.

In this study, we further investigate the relationship between hostile sexism and support for political violence among American subjects.Footnote 3 It is important to identify public attitudes that are correlated with increased tolerance or support for political violence, given that scholars argue that actors that employ political violence often are enhanced, motivated, and legitimized by public sympathy (see Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw2000; Kruglanski and Fishman Reference Kruglanski and Fishman2006; Kushner Reference Kushner1996; Ross Reference Ross1993; Weinstein Reference Weinstein2005). This suggests that public tolerance for political violence may lead to increased probability of occurrence of political violence. To interrogate the relationship between hostile sexism and endorsement of political violence, we evaluate two factors that we argue mediate the effect of hostile sexism on support for political violence: social dominance orientation and political illiberalism. We test for a mediated relationship using two different operationalizations of support for political violence: one of which measures support for political violence in the abstract and another which measures support for political violence in specific, outlined contexts.

Using original survey data that we collected on more than 1,400 US subjects, we produce two findings. First, hostile sexism is a significant, positive, and substantive predictor of support for both measures of political violence. Second, we find that the impact of hostile sexism on political violence is significantly and substantively mediated through social dominance orientation and political illiberalism for both measures of political violence. Our study contributes to the literature by providing a better understanding of how hostile sexism is linked with support for political violence while examining the importance of both sociological/psychological and political factors to the relationship. Moreover, in doing so, our study demonstrates a link between patriarchy and violence in ways that complement existing literatures on misogyny and the potential for politically motivated violence against women.

Hostile Sexism and Support for Political Violence, A Mediated Relationship

We theorize that the relationship between hostile sexism and political violence is partially mediated through social dominance orientation and political illiberalism, and that these two mediators help us to better understand why hostile sexism is associated with violent extremist political attitudes. Before outlining our theory, it is useful to define these two terms. Social dominance orientation, or SDO, is an individual personality trait in which the subject desires to maintain anti-egalitarian and differentiated hierarchies among social groups. Subjects who exhibit SDO view society as a brutal, zero-sum competition between social groups and seek to boost or preserve the dominant status of their own group over other/rival social outgroups (Perry, Sibley, and Duckitt Reference Perry, Sibley and Duckitt2013; Pratto et al. Reference Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth and Malle1994). SDO-oriented subjects tend to prefer ideologies that draw a sharp, hierarchical distinction among social groups, such as nationalism or racism (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Sidanius, Kteily, Sheehy-Skeffington, Pratto, Henkel, Foels and Stewart2015), and SDO has been linked in empirical studies to implicit bias against members of outgroups (Hewstone et al. Reference Hewstone, Clare, Newheiser and Voci2011; Pratto and Shih Reference Pratto and Shih2000).

We define political illiberalism in our study as an individual preference for nondemocratic modes of governance, in particular autocratic rule by a political “strong man” who is unencumbered by rule of law, free elections, or political institutions that check and balance power. We expect SDO and political illiberalism to be predictors of one another in a survey setting — that is, we expect individuals exhibiting SDO to also be more likely to be politically illiberal and skeptical of democratic practices that equalize power among social groups. This is consistent with research by Šerek and Mužik (Reference Šerek and Mužík2021) who find a correlation between SDO and disregard for core democratic values. However, we also see SDO and political illiberalism as distinct attitudes that have an independent relationship, both empirically and logically, with hostile sexism and support for political violence. Our analysis, detailed below, is consistent with this contention.

Hostile Sexism, Social Dominance Orientation, and Support for Political Violence

We theorize that hostile sexism is strongly associated with SDO. This is a logical assumption given that SDO is an outlook that favors maintaining traditional social hierarchies, and views the prospect of egalitarianism among all social groups, including between men and women, with hostility. We expect individuals who display high levels of SDO to also exhibit higher levels of outgroup prejudice and to be greatly affected by inter-social group threat, both of which produce increased support for the use of political violence to maintain the hierarchical status quo between dominant and marginalized social groups. In this section, we further outline our theoretical expectations about hostile sexism, SDO, and political violence, and anchor them to several strands of existing literature.

Empirical research has found that individuals exhibiting SDO are also more likely to express hostile sexist views (Christopher and Mull Reference Christopher and Mull2006; Lee Reference Lee2013; Sibley, Wilson, and Duckitt Reference Sibley, Wilson and Duckitt2007). Various elements of SDO help to explain its link as a personality trait to endorsement of hostile sexism. Because a key component of SDO is anti-egalitarianism among social groups, individuals displaying SDO also exhibit hostile sexism and negative attitudes toward attempts to equalize power relations between men and women (Austin and Jackson Reference Austin and Jackson2019).Footnote 4 Moreover, because SDO is strongly motivated by a perception of zero-sum competition between social groups, individuals presenting SDO are more likely to also display prejudice against traditionally marginalized outgroups deemed to be “inferior” and to compete against them for social status, resources, and power. Extending and testing this proposition, scholars have found that individuals exhibiting SDO are more likely to bear sexist attitudes toward women and to display hostility toward feminism and attempts to foster women’s empowerment (Duckitt Reference Duckitt, Sears, Huddy and Jervis2003, Reference Duckitt2006; Fiske et al. Reference Fiske, Amy, Glick and Xu2002; Sibley, Wilson, and Duckitt Reference Sibley, Wilson and Duckitt2007). Finally, Sibley, Wilson, and Duckitt (Reference Sibley, Wilson and Duckitt2007) find that male subjects scoring high on SDO indices view women as threatening social competitors and react with overt hostility to the prospect of women’s empowerment or the equalization of socio-political status between men and women. In this study, we therefore expect subjects who hold hostile sexist attitudes to also be more likely to display SDO.

SDO and support for political violence can be linked by two interrelated theoretical mechanisms. First, SDO is strongly associated with hostility toward and prejudice against minority groups and social outgroups (Hewstone et al. Reference Hewstone, Clare, Newheiser and Voci2011; Pratto and Shih Reference Pratto and Shih2000). This is significant as prejudice, racism, xenophobia, and intolerance toward social outgroups have been found to be strong predictors of support for political violence (Piazza and Van Doren Reference Piazza and Van Doren2023). This is because outgroup intolerance prompts outgroup othering and dehumanization. Scholars argue that prejudicial attitudes facilitate the social othering and dehumanization of outgroup members, which are identified as necessary ingredients for reducing inhibitions against the use of violence (see Bandura Reference Bandura1999; Čehajić, Brown, and González Reference Čehajić, Brown and González2009; Waytz, Epley, and Cacioppo Reference Waytz, Epley and Cacioppo2010). Piazza (Reference Piazza2023a) demonstrates that dehumanization of socio-political others/outgroups is a key contributor to expressed tolerance of or support for the use of political violence.

Second, SDO is partly motivated by the perception of dominant versus marginalized social group competition. In theory, individuals who exhibit SDO could be expected to embrace pro-status quo political ideologies that condemn political violence, provided they live in inegalitarian traditional societies that offer little opportunities for outgroup empowerment or socio-political mobility (Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1988; Duckitt and Bizumic Reference Duckitt and Bizumic2013; Jost, Banaji, and Nosek Reference Jost, Banaji and Nosek2004; Sidanius and Pratto Reference Sidanius and Pratto2001; Webber et al. Reference Webber, Kruglanski, Molinario and Jasko2020).Footnote 5 However, SDO-oriented individuals from traditionally dominant social groups living in societies where historically marginalized social groups are increasing their representation and are seeking greater empowerment and equality — as some would say is the case in the United States today — are likely to regard increased social egalitarianism as threatening to their group status. Using intergroup conflict theory, Brewer (Reference Brewer1999) identifies this situation as ripe for increased political violence. Brewer explains that dominant social groups respond to the perception of threat posed by rival groups by increasing their identification with ingroup members and sharpening their aversion, fear, and loathing toward outgroup members. This makes the use of political violence less taboo. Bartels (Reference Bartels2020) produced a finding that is consistent with this theoretical argument. In his public opinion study, he found that white subjects who believe that non-whites are gaining greater access to political power in the United States are more likely to express support for political violence.

These theoretical mechanisms are supported by a body of literature that finds an empirical link between SDO and support for political violence. Experimental studies find that individuals scoring high on SDO personality trait indices are more likely to express support for the use of political violence (Henry et al. Reference Henry, Sidanius, Levin and Pratto2005; Mitchell and Sidanius Reference Mitchell and James1993; Thomsen, Green, and Sidanius Reference Thomsen, Eva and Sidanius2008). In their experiment on individual attributes predicting engagement in contentious politics, Lemieux and Asal (Reference Lemieux and Asal2010) found that individuals exhibiting high levels of SDO were more likely to indicate that they would be willing to engage in terrorism or political violence to achieve their political objectives. Moving beyond intended behavior, Kearns et al. (Reference Kearns, Asal, Walsh, Federico and Lemieux2020) find in a survey experiment that high SDO individuals were more likely to report having engaged in violent protests. Other scholars have found SDO to be an attribute that predicts subject support for political violence in public opinion studies in multiple countries (Ozor Reference Ozor2017; Troian et al. Reference Troian, Baidada, Arciszewski, Apostolidis, Celebi and Yurtbakan2019; Vegetti and Littvay Reference Vegetti and Littvay2022).Footnote 6

Hostile Sexism, Political Illiberalism, and Support for Political Violence

We theorize that the relationship between hostile sexism and support for political violence is also mediated through increased political illiberalism, which we define as disdain for democratic norms, values, institutions, and practices, and endorsement of authoritarian modes of governance. We argue that hostile sexism is associated with illiberal attitudes and preferences, and that in turn, individuals exhibiting illiberalism are less constrained by the pacific and nonviolent norms of political behavior that democracy reinforces. Consequently, such individuals are more likely to be tolerant of the use of political violence, as opposed to addressing their political preferences or grievances through nonviolent, democratic behaviors. Multiple bodies of work lend support to our contentions.

To start, there are several literatures that suggest a potential link between hostile sexism and political illiberalism. To our knowledge, no individual-level, survey-based research has examined and found a statistical relationship between hostile sexism and political illiberalism or support for authoritarian political rule, save one. El Kurd (Reference El Kurd2018) finds that survey subjects in Muslim countries that exhibited sexist attitudes were also less likely to endorse democracy as a system of government and more likely to oppose the implementation of free multiparty democratic elections. These findings are, of course, derived from a very different social context than the United States. However, they are consistent with our expectation that hostile sexism is associated with political illiberalism. Beyond this study, other scholars using survey research have found that that individuals harboring sexist attitudes are less likely to support minority group rights and specific individual rights, suggesting a hostility to some key elements of liberal democratic rule. For example, Dunbar et al. (Reference Dunbar, Sullaway, Blanco, Horcajo and De La Corte2007) found hostile sexist individuals were less likely to endorse support for racial and ethnic minority group rights; Masser and Abrams (Reference Masser and Abrams1999) found that sexist individuals were less supportive of LGBTQ rights and protections; while Cizmar and Kalkan (Reference Cizmar and Kalkan2023) found sexists to be unsupportive of abortion rights.

On a more macro level, scholars have identified a relationship between illiberal political rule in countries and assaults on gender equality (see literature review in Piccone Reference Piccone2017). Clifford (Reference Clifford2020) documents a correlation between gender equality and democratic rule in a sample of countries, suggesting conversely that there is a connection between political liberalism and sexism. Scholars note the prominent role that misogyny and hostility to gender equality play in the rhetoric, political mobilization strategies, and public policies of politically illiberal authoritarian movements and governments world-wide (Chenoweth and Marks Reference Chenoweth and Marks2022; Kaul Reference Kaul2021; Kaul and Buchanan Reference Kaul and Buchanan2023; Mannheim Reference Mannheim2023; Sanders and Jenkins Reference Sanders and Jenkins2022). Not surprisingly, scholars have observed that supporters of populist illiberal politicians and parties in several countries exhibit strong sexist and misogynist attitudes.

For example, in analyses of voter attitudes Anduiza and Rico (Reference Anduiza and Rico2022) found that sexism is associated with support for the far-right in Spain, while Christoffersson (Reference Christoffersson2023) observes that sexist attitudes are strong predictors for electoral support for radical right parties in Europe. Multiple studies of voters in the United States find an association between sexism and support for Donald Trump, an American politician with strong authoritarian and illiberal tendencies who attracts authoritarian and illiberal voters (Donovan Reference Donovan2019). For example, scholars have found that hostile sexism predicted voter support for Trump (Bock, Byrd-Craven, and Burkley Reference Bock, Byrd-Craven and Burkley2017; Knuckey Reference Knuckey2019; Schaffner, MacWilliams, and Nteta Reference Schaffner, MacWilliams and Nteta2018) while Valentino, Wayne, and Oceno (Reference Valentino, Wayne and Oceno2018) determined that hostile sexism linked to anger, as opposed to fear, was an important driver of voter support for Trump in the 2016 election. These findings further suggest to us that hostile sexist individuals are more amenable to illiberal political rule.

In turn, a significant body of research finds that politically illiberal individuals are more likely to endorse or support the use of political violence. Examining survey subjects in multiple countries, Bartusevičius, van Leeuwen, and Petersen (Reference Bartusevičius, van Leeuwen and Petersen2020) found that those that held autocratic political views were more likely to express support for political violence. Surveyed individuals in Muslim or Arab countries who are skeptical toward democracy as a system of government or dismissive of democratic rights are also more likely to support terrorism, political violence, or violent extremist organizations (Kaltenthaler, et al. Reference Kaltenthaler, Miller, Ceccoli and Gelleny2010; Piazza 2019; Piazza Reference Piazza2022a; Zhirkov, Verkuyten, and Weesie Reference Zhirkov, Verkuyten and Weesie2014). Finally, American subjects who hold illiberal political views and preferences tend to be more supportive of political violence. Piazza (Reference Piazza2023b) found that illiberal populist individuals are more likely to endorse the use of political violence, while Bartels (Reference Bartels2020) uncovers an association between antidemocratic attitudes and support for the use of violence to preserve traditional values among self-identified Republicans in the United States.

We argue that the mechanism linking political illiberalism to support for political violence is rooted in the role that democratic norms, institutions, and practices play in translating potentially violent political mobilization into nonviolent political participation, and preserving peaceful and orderly politics within democracies. Democracies, through norms, practices, and institutions, constrain violent political participation and promote nonviolent political expression and contestation. Scholars argue that when these democratic norms, institutions, and practices are weakened, disrupted, or widely distrusted, political violence is more difficult to constrain (see Przeworski Reference Przeworski1991; Riker Reference Riker1983). When the public loses confidence in the democratic system, support for political violence and violent mobilization becomes a more distinct possibility (Albertson and Guiler Reference Albertson and Guiler2020; Berlinski et al. Reference Berlinski, Doyle, Guess, Levy, Lyons, Montgomery, Nyhan and Reifler2023; Piazza Reference Piazza2022b). We expect this process to be reflected in our analysis of individual attitudes toward the acceptability of political violence. Individuals in our study who do not trust or respect democratic norms, institutions, and practices are more likely to be susceptible to violent political mobilization and to therefore view the use of political violence as more acceptable.

Hypotheses

Given these theoretical contentions and their supportive literatures, we test three hypotheses. First, we expect to reproduce the results produced by Kalmoe and Mason (Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022b), albeit with a more robust test given that we examine the relationship between hostile sexism and support for abstract and specific instances of political violence. Our first hypothesis is:

H1 Subjects who express hostile sexism are more likely to support political violence.

Second, we expect that the relationship between hostile sexism and support for political violence — both abstract and specific — is mediated through social dominance orientation of subjects and political illiberalism and support for nondemocratic rule. Our second and third hypotheses are:

H2 Social dominance orientation mediates the effect of hostile sexism on support for political violence.

H3 Political illiberalism mediates the effect of hostile sexism on support for political violence.

Note, we do not hypothesize a specific direction of causation between hostile sexism, social dominance orientation or political illiberalism, and support for political violence, nor do our empirical tests permit such a test of causation. Rather, we expect the independent, mediating, and dependent variables to be strongly associated with one another in ways that provide more information as to how and why hostile sexists express stronger support or tolerance for political violence.Footnote 7 Furthermore, we do not expect a moderated relationship between hostile sexism, social dominance orientation, political illiberalism, and support for political violence. That is, we do not think that hostile sexism is associated with increased support for political violence conditional on its interaction with social dominance orientation or political illiberalism. Instead, we argue that the independent variables and the mediators bear independent significant relationships with the dependent variable and do so in a way that provides a more complete picture of why hostile sexism is associated with endorsement of political violence.Footnote 8

Research Design

To test the hypotheses of the study we designed and fielded an original online survey of 1,428 subjects residing in the United States using the Lucid Theorem online survey panel. Lucid provides an online survey panel that is broadly representative of the US adult population (Coppock and McClellan Reference Coppock and McClellan2019). Moreover, other studies of attitudes on political violence have used the Lucid panel for their analyses (for example, Armaly, Buckley, and Enders Reference Armaly, Buckley and Enders2022; Armaly and Enders Reference Armaly and Enders2022). The survey was conducted between July 25 and August 2, 2023. We fielded the survey in several tranches at different times and across different days of the week to maximize the chances of participation from subjects across the United States. Subjects who took the survey resided in all 50 US states. Those that reported living in other countries were excluded from the study.

All subjects were pre-briefed, provided prior consent, and were thoroughly debriefed.Footnote 9 Subjects who failed to provide consent were eliminated from the study, as were subjects who ended the survey before answering the last question. Scholars have argued that inattentiveness may affect subject responses to survey questions about political violence (Westwood et al. Reference Westwood, Grimmer, Tyler and Nall2022a). We therefore included a commitment check and several attention checks throughout the survey. Subjects who failed to affirm a commitment checkFootnote 10 were removed from the survey, as were subjects who failed an attention check question midway through the surveyFootnote 11 and an attention check question three quarters of the way through the survey.Footnote 12 Overall, 387 subjects were eliminated from the survey either for failing to provide consent, declining to commit, failing one of the attention checks, or failing to finish the survey.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable of the study is support, endorsement, or tolerance of political violence: the use of violence to achieve a political goal or to express a political viewpoint. Motivated by the debate between Kalmoe and Mason and Westwood and co-authors (Kalmoe and Mason Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022a; Westwood, et al. Reference Westwood, Grimmer, Tyler and Nall2022a, Reference Westwood, Grimmer, Tyler and Nall2022b) on surveying Americans about their support for political violence, we develop two different operationalizations of subject support for political violence.Footnote 13 In both instances, it is important to note, we use a narrower definition of “violence” than that typically used in feminist research, restricting our focus to threats and acts of physical violence rather than a broader spectrum of acts constituting violations of integrity (see Krook Reference Krook2020). While this choice does not allow us to examine all forms of political violence, it does allow us to compare our findings directly with the work of Kalmoe and Mason (Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022a), whose work inspired this study. Based on emerging findings in the literature on gendered political violence and violence against women in politics (Bjarnegård, Melander, and True Reference Bjarnegård, Melander and True2020; Krook Reference Krook2020; Sanín Reference Sanín2020), however, we expect that future research is likely to find even stronger associations between hostile sexism and non-physical forms of violence.

Our first measure focuses on subject support for political violence in the abstract. For this measure, we created an additive index of eight questions asking subjects whether they generally agree that political violence — in the form of physical attacks, threats of violence, and attacks against property — is acceptable, is needed to advance an individual’s personal political goals, and may be used to express disapproval of the government, to deter the government, to send a message to politicians, or to respond to political opponents.Footnote 14 This measure ranges from 8, indicating a low level of support for political violence, to 32, indicating a high level.Footnote 15 We derived several of these questions based on validated survey items used in other studies (for example, Kalmoe Reference Kalmoe2014; Kalmoe and Mason Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022b; Uscinski and Parent Reference Uscinski and Parent2014) as well as original questions of our own. The component questions, along with scalability statistics and frequency distributions, are detailed in the Appendix. Support for political violence, as operationalized by the abstract measure, is low in the sample. The modal subject (19.43% of the sample) expressed the absolute lowest level of support (8 on the 8 to 32 point scale) for the use of political violence in the abstract, whereas the median subject scored a 12. Less than 10% of subjects scored a 23 or higher (on the 8–32 point scale), which is associated with moderate to high levels of support for political violence, when presented abstractly.

The second measure explores subjects’ support for political violence in the context of specific instances of political violence. For this measure, we created an additive index of four questions that ranges from 4, indicating a low level of support for political violence, to 16, indicating a high level.Footnote 16 In the questions, we provided accounts of fictitious incidents where an individual was charged with assault for engaging in an act of political violence against other individuals. We provided two accounts: one where the alleged assailant was identified as a Republican who used political violence against Democrats, and another where the alleged assailant was a Democrat who used political violence against Republicans. We then asked subjects whether they thought the individual was justified in engaging in the violent behavior depicted and whether they were sympathetic to the individual.Footnote 17 Subject responses to these four response items were then constructed into an additive index.Footnote 18

This operationalization was inspired by Westwood et al. (Reference Westwood, Grimmer, Tyler and Nall2022a) who argue that survey subjects often exhibit different degrees of support for political violence when presented with scenarios depicting specific acts of political violence. The component scenarios and questions for the second operationalization of political violence, along with scalability statistics and frequency distributions, are detailed in the Appendix. In the sample, support for political violence when provided with a specific context is a bit higher than support for abstract political violence, but still modest overall. The modal subject (55.6%) scored a 7 on the 4–16-point scale, exhibiting a moderately low level of sympathy or support for the use of political violence in the specific vignettes. The median subject also scored a 7 on the specific political violence scale. Less than 10% of subjects scored between 11 and 16, which indicates a moderate to high level of support for political violence in a specific context.Footnote 19 Finally, the two operationalizations of political violence are correlated with one another (p = 0.51 ***).Footnote 20

Our objective in using two measures of support for political violence — support in the abstract and support for political violence when it is presented in a specific context — and in using survey questions validated in previous studies (for example, Kalmoe Reference Kalmoe2014; Kalmoe and Mason Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022b; Uscinski and Parent Reference Uscinski and Parent2014) or derived from survey items used in other studies (Westwood et al. Reference Westwood, Grimmer, Tyler and Nall2022a) is to cover all bases. We are confident that our outcome variables capture all aspects of support or tolerance for threats and acts of physical violence for political ends by the subject.

Independent Variable

The independent variable of the study is subject level of hostile sexism. To operationalize hostile sexism, we use validated survey questions from two sources. First, we employed five survey questions Schaffner (Reference Schaffner2021) identifies as optimized for the measurement of sexism in public opinion research. These questions — detailed in the Appendix — compose what Schaffner terms a “reduced hostile sexism battery” that is highly efficient and valid. The questions ask subjects about their agreement or disagreement with statements that depict women as power-hungry, controlling of men, unappreciative, too easily offended, and prone to exaggeration about problems they face in contemporary society.

Second, we use six survey questions from the American National Election Survey (ANES) that measure “modern sexism.” These questions, also detailed in the Appendix, measure sexist attitudes associated with women’s demands for equality, allegations of harassment, social progress toward equality between men and women, depictions of women in media, and women’s advocacy. These sets of questions are scalable,Footnote 21 and we use them to create an additive index ranging from 12 to 44. The distribution of hostile sexist attitudes among subjects is rightward skewed, in that the median subject had a hostile sexism index score of 24.5 on the 12 to 44 scale. However, subjects cluster around the median score in a normal distribution, as demonstrated by a frequency distribution figure in the Appendix.

Mediators

We hypothesize that the relationship between hostile sexism and support for political violence is mediated through two mediating variables: SDO and political illiberalism/support for authoritarian rule. We measure the mediating variables in the following way: To operationalize SDO, we use validated survey questions from Pratto et al. (Reference Pratto, Çidam, Stewart, Zeineddine, Aranda, Aiello, Chryssochoou, Cichocka, Christopher Cohrs, Durrheim, Eicher, Foels, Górska, Lee, Licata, Liu, Li, Meyer, Morselli, Muldoon, Muluk, Papastamou, Petrovic, Petrovic, Prodromitis, Prati, Rubini, Saab, van Stekelenburg, Sweetman, Zheng and Henkel2013) and from the ANES to build an additive index ranging from 10, indicating that the subject exhibits a low level of SDO, and 25, indicating a high level of SDO. The survey questions used to build the SDO index ask subjects about their attitudes about the desirability of social group equality, whether inequality is a problem today, and whether all social groups should be considered when priorities are being set. In the sample, SDO, as an attitude, is somewhat skewed left. Very few subjects exhibit high levels of SDO — only around 10% have SDO index ratings of 18 to 25 in the 10–25 index — however almost half of the sample exhibits a moderate (14 in the 10–25 index) SDO rating or higher, suggesting that SDO is far from rare in the sample. Frequency and scalability statistics for the SDO measure are displayed in the Appendix.

To operationalize political illiberalism and support for nondemocratic rule, we use two questions from Drutman, Goldman, and Diamond (Reference Drutman, Goldman and Diamond2020) and employ them to construct an additive index that ranges from 2, indicating little support for politically illiberal rule, to 8, indicating a high level of support.Footnote 22 The two component questions of the illiberalism measure ask subjects about whether they think the following scenarios would be good or bad ways of governing the United States: having a “strong” leader who is not checked by Congress or elections; and having the military suspend elections, close Congress, and temporarily take charge of government in order to address corruption. The plurality of subjects, around 34%, completely reject both of these scenarios while very few subjects, less than 10%, exhibit high levels of political illiberalism (scoring a 6 or higher on the 2–8 point scale). However, there is some middling support for nondemocratic rule in the sample. Around 34.5% of subjects scored a 4 or a 5 on the 2–8 point illiberalism scale. Frequency distribution and scalability statistics for the political illiberalism measure are presented in the Appendix.

In all models, we also include a set of demographic and attitudinal control variables. We control for subjects’ age, gender, household income, employment status, race, partisan affiliation, religious identity and religious “born again” identification. We also control for subjects’ level of political engagement, news consumption habits, trait aggression — the propensity of an individual to be aggressive — and regional residence within the United States. These are standard controls used in previous public opinion studies of support for political violence (Armaly, Buckley, and Enders Reference Armaly, Buckley and Enders2022; Armaly and Enders Reference Armaly and Enders2022; Piazza Reference Piazza2023a, Reference Piazza2023b; Piazza and Van Doren Reference Piazza and Van Doren2023). Finally, we included a natural log measure of the time it took the subject to take the survey.

The median age of subjects was 45 and 48.5% of subjects identified as male. The median subject reported an annual household income of $35,000 to $39,999. Around 10.1% of subjects reported being unemployed and looking for work, while the median subject reported having attended college but not obtaining a bachelor’s degree. Around 71.4% of subjects identify as white, non-Hispanic, 10.6% as Black, non-Hispanic, 9.3% as Hispanic or Latino, 5.3% as Asian or Pacific Islander, and 1.1% as Native American or Indigenous. Around 41.9% of subjects in the sample identified as Democrats, and around 36.3% identified as Republicans. The remainder either identified as Independents or listed no party identification. For political engagement, around 51.8% stated that they had contacted a member of government, urged another person to vote, or participated in a political meeting or protest at least once in the past three years. Around 73.6% reported voting in the 2020 Presidential election. Around 62.0% identified as Christian, while 33.8% identified as “born again.” The median subject reported following the news several times per week, while 8.3% stated that they mostly relied upon conservative news sources such as Fox News, Newsmax, or conservative online sites and talk radio. Trait aggression adhered to a fairly normal frequency distribution in the sample with the median subject scoring between 8 and 9, and the mean subject scoring 8.9 on the 4–16 trait aggression index (derived from Kalmoe Reference Kalmoe2014). Around 20.1% of subjects hailed from the US Northeast, 38.9% from the South, 19.3% from the Midwest, and 21.7% from the West. The median subject took around 11.7 minutes to finish the survey.

Results

The results provide supportive evidence for all three of our hypotheses. We discuss these in turn.

Support for Hypothesis 1: Hostile Sexism and Support for Political Violence

We find that subjects who exhibit hostile sexist attitudes are statistically more likely to express support for political violence. We find this both when the dependent variable is operationalized as abstract support for political violence and support for more specific instances of political violence. Tabled full results are presented in the Appendix.Footnote 23 Figures 1a, b and 2a, b below provide a graphical depiction of the results by showing the slope of the relationship between hostile sexism and support for political violence.

Figure 1. Hostile Sexism and Support for Political Violence, Regression Analysis Results.

a. Support for Political Violence, Measure 1 (Abstract)

Note: All control variables included.

b. Support for Political Violence, Measure 2 (Specific Example of Political Violence)

Note: All control variables included.

In Figure 1a, b, we observe that increasing subjects’ hostile sexism index scores from their lowest to highest levels results in a linear increase in subjects’ expressed support for abstract (β = .262 [CI .217–.307]) and specific (β = .034 [CI .017–.051]) political violence. In substantive terms, an increase from the minimum to the maximum hostile sexism index score corresponds with a 77% increase in subject support for political violence in the abstract and a 14% increase in subject support for the specific instances of political violence. This is substantively consistent with findings by Kalmoe and Mason (Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022b), who also found hostile sexism to be associated with increased support for partisan political violence in subjects, and is empirically consistent with Westwood and co-authors (Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022a) contention that subjects tend to exhibit lower levels of support for political violence when asked about specific acts of political violence.

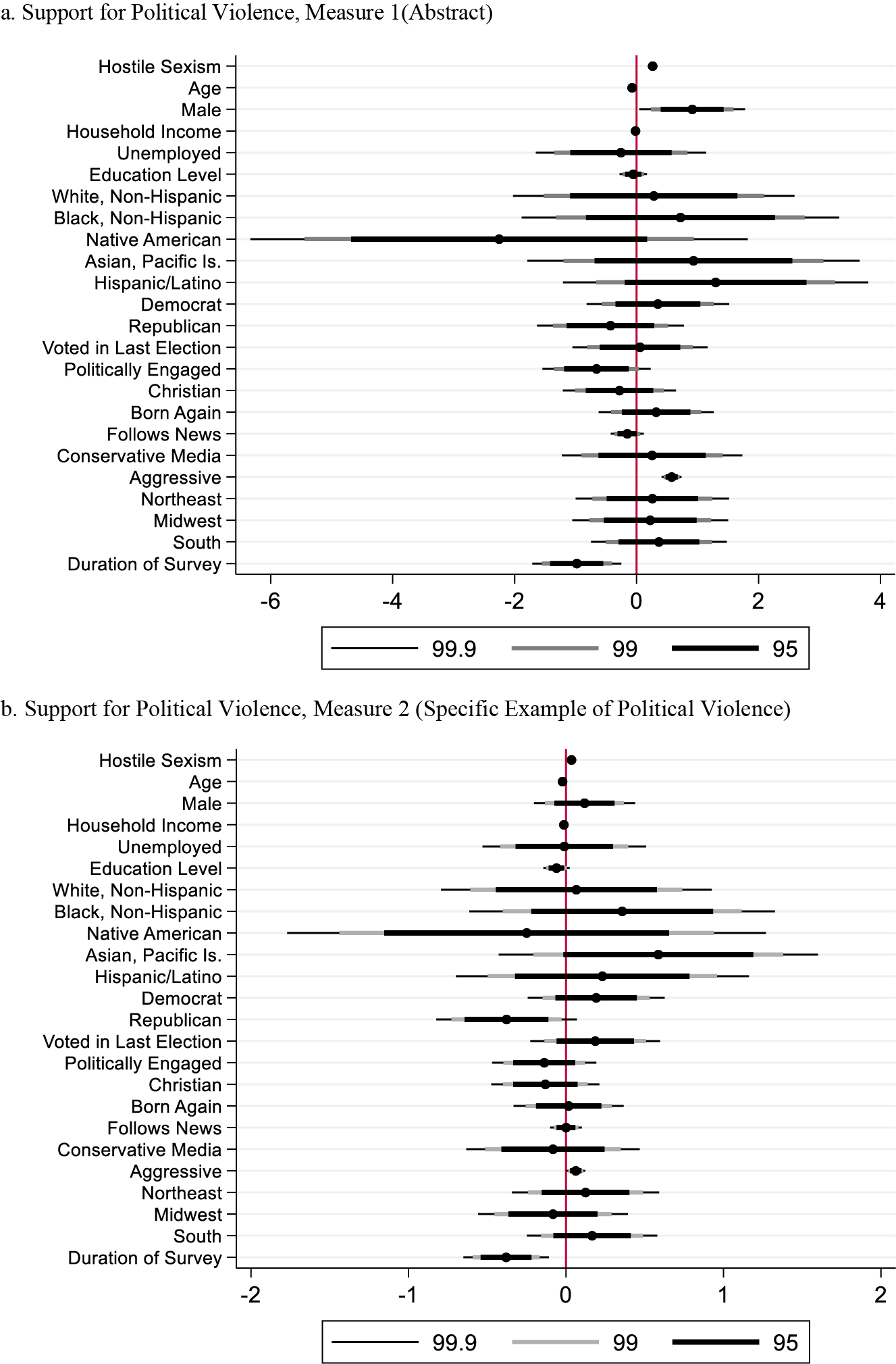

Hostile sexism is a positive, significant predictor of support for both types of political violence despite several of the control variables also being significant. This is illustrated in Figure 2a, b.

Figure 2. Coefficient Plots, Hostile Sexism and Support for Political Violence.

a. Support for Political Violence, Measure 1 (Abstract)

b. Support for Political Violence, Measure 2 (Specific Example of Political Violence)

In these figures, we present coefficient plots for the variables in the models. This allows us to compare the relative substantive impact of hostile sexism on support for political violence compared to other covariates. These figures depict the impact of one-unit changes of the independent variables on the dependent variable. Most notably, across both sets of models, subjects exhibiting higher levels of trait aggression are more likely to also support political violence in the abstract (β = .575 [CI .477–.671]) and specific acts of political violence (β = .061 [CI .025–.097]). This is approximately double the substantive effect of hostile sexism on support for both measures of political violence. Though several of the other controls are significant, positive predictors of one or the other measure of support for political violence — namely gender, education, Latino identification, and Asian Pacific Islander identification — only trait aggression is significant and positive in both models.

Two other controls are consistently significant, but negative, predictors of support for both measures of political violence: age and duration, or the time the subject took to complete the survey. Older subjects are less likely to express support for political violence in the abstract (β = -.074 [CI -.092–-.056]) and for specific political violence (β = -.022 [CI -.028–-.015]). However, the substantive impact is approximately the same or lower than that of hostile sexism. Subjects who took longer to complete the survey are substantively less likely to support abstract political violence (β = -.981 [CI -1.415–-.546]) and specific political violence (β = -.380 [CI -.541–-.218]). This effect is between 3 and 10 times larger than hostile sexism.Footnote 24

Support for Hypotheses 2 and 3: Effect of Hostile Sexism on Support for Political Violence is Mediated through Social Dominance Orientation and Political Illiberalism

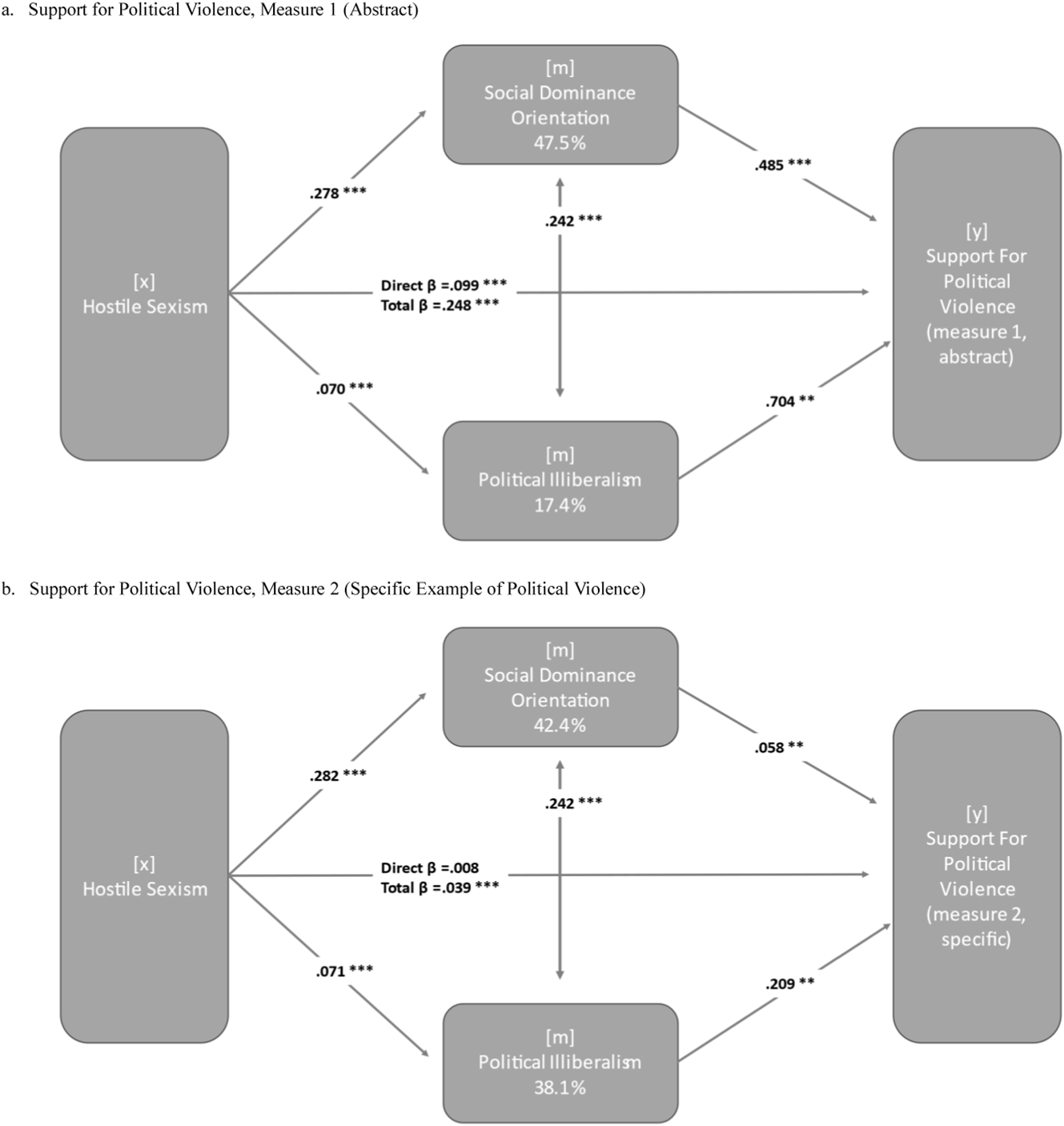

We also find the relationship between hostile sexism and support for both measures of political violence to be partially mediated through SDO and political illiberalism or support for nondemocratic rule. In Figure 3a, we present the results of the mediation analysis for our measure of support for political violence in the abstract.

Figure 3. Mediation Analysis Results, Hostile Sexism, Moral Absolutism, SDO, and Support for Political Violence.

a. Support for Political Violence, Measure 1 (Abstract)

Notes: Bootstrapped iterations: 1,000

Percent mediated noted for each mediator

Indirect Effect (SDO): .135***

Indirect Effect (Political Illiberalism): .049**

b. Support for Political Violence, Measure 2 (Specific Example of Political Violence)

Notes: Bootstrapped iterations: 1,000

Percent mediated noted for each mediator

Indirect Effect (SDO): .017**

Indirect Effect (Political Illiberalism): .014**

The mediation analysis demonstrates that hostile sexism positively predicts both SDO (β = .278 [CI .257–.300]) and political illiberalism (β = .070 [CI .055–.084]), and in turn both SDO (β = .485 [CI .392–.578]) and political illiberalism (β = .704 [CI .556–.853]) are positive predictors of subject support for political violence in the abstract. Moreover, approximately 47.5% of the effect of hostile sexism on support for political violence in the abstract is mediated through increased SDO, while 17.4% is mediated through political illiberalism. SDO and political illiberalism are significant predictors of one another (r2 = .242***), but multicollinearity is not evident in the model.Footnote 25 Taken together, the majority, 64.9%, of the effect is mediated through our two theorized mediators.

In Figure 3b, the results of the mediation analysis for our more specific measure of support for political violence are presented.

We find that the effect of hostile sexism on support for specific instances of political violence is also mediated through SDO and political illiberalism. In this model, hostile sexism again positively predicts SDO (β = .282 [CI .261–.303]) and political illiberalism (β = .071 [CI .057–.085]) and, in turn, SDO (β = .058 [CI .022–.095]) and political illiberalism (β = .209 [CI .151–.266]) predict support of specific political violence. Around 42.4% of the relationship between hostile sexism and support for specific political violence is mediated through SDO while around 38.1% is mediated through political illiberalism. Though hostile sexism was found previously to be a highly significant, though less substantive, predictor of support for specific acts of political violence, the combined mediation effect of our two mediators is much larger: 79.5% of the effect is mediated through both of our theorized mediators.

Conclusion

To summarize, we find that hostile sexism is associated with support for political violence, regardless of how support for political violence is measured. Individuals exhibiting hostile sexism are more likely to tolerate and endorse the use of political violence, both when political violence is presented as an abstract behavior and when it is presented as a specific incident. Moreover, hostile sexism and support for political violence are substantively linked to one another through SDO and political illiberalism.

We interpret these findings in the following way: the findings suggest to us that sexist individuals are more tolerant of political violence because they are also vested in maintaining traditional social hierarchies and repressing demands for equality from traditionally marginalized social groups. Such individuals, we suspect, are more likely to view the use of political violence as a tolerable means to reinforce social group inegalitarianism and resist redistribution of social power among groups. At the same time, such individuals reject liberal democratic norms, practices, and institutions — the very tools that can be employed to empower traditionally marginalized social groups and that are necessary for constraining violent political behavior in democratic societies. Our findings have disquieting implications for a changing country where traditionally marginalized people are seeking representation, empowerment, and dignity. These changes, rightly celebrated and eagerly anticipated by some, are likely to inflame SDO-oriented individuals and fuel political illiberalism among some segments of society, creating an environment in which support for political violence is normalized. With increased normalization, extremist actors may be more willing to engage in political violence with greater impunity.

We view our study as a first step in better understanding the relationship between hostile sexism and support for political violence. This is important because, as previously noted, scholars have documented the link between sexist attitudes and behaviors and acts of political violence, particularly against women in politics (see Bjarnegård, Melander, and True Reference Bjarnegård, Melander and True2020; Krook Reference Krook2018, Reference Krook2020, Reference Krook2022; Krook and Sanín Reference Krook and Sanín2020; Raney Reference Raney2023; Sanín Reference Sanín2020, Reference Sanín2023; Wineinger Reference Wineinger2023). However, more work is needed to further understand the relationship, and our study suggests some future research directions. Our study starts by finding support for an association between hostile sexism and political violence. However, it does not establish a causal relationship. Future work could leverage experimental designs or other techniques to identify a causal link.

Moreover, though we determine that they are conceptually distinct and have a distinct effect on support for political violence, we find in our study that our two mediators, SDO and political illiberalism, are predictors of each other. Future research might try to disentangle this relationship and examine its implications for the impact of hostile sexism on political violence. It is possible that there is an ordered relationship between the mediators. Scholars may investigate this further using serial mediation analysis or other techniques.

Additionally, we found SDO and political illiberalism to partially mediate the impact of hostile sexism on support for political violence. Our analysis suggests that around 80% of the effect of sexism on political violence support is mediated through one of these two mediators. Future research might search for additional mediators or serial mediators, including psychological traits and attitudes such as moral absolutism, interpersonal distrust, trait rigidity, and other factors that provide a more complete understanding of the association between hostile sexism and tolerance of political violence.

Though our study is focused on hostile sexism and political violence in the United States, we suspect that many of the findings of our study are generalizable to other countries as well, given the prevalence of patriarchy cross-nationally (see Brandt Reference Brandt2011). That said, the mediation effect of illiberalism may work differently in countries with well-established democratic norms and institutions versus anocracies or dictatorships, where such norms and institutions are weaker or are absent. The burgeoning literature on gender and populism, democratic backsliding, and autocratization, however, suggests that hostile sexism is prevalent in these contexts and may play an important role in motivating and justifying political violence, particularly against women seeking to participate in political life (Lombardo, Kantola, and Rubio-Marin Reference Lombardo, Kantola and Rubio-Marin2021). Our study offers some first steps for exploring these broader trends, both in other countries and employing broader feminist definitions of violence.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X24000400.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.