The Colombian peace process between the government and the left-wing guerrilla FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) has been internationally celebrated for its unprecedented focus on women's experiences of armed conflict. After substantial efforts by Colombian civil society led to an exceptional inclusion of women in all aspects of the negotiations, the Havana Peace Accords, ratified in 2017, recognized the particular effects of war on women, most notably in terms of sexual violence (Gindele et al. Reference Gindele2018; Salvesen and Nylander Reference Salvesen and Nylander2017). But the everyday violence that women may face in their homes was not acknowledged in the otherwise gender-comprehensive accords.

Conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) is a known feature of many conflicts worldwide. It does not occur in a vacuum, but it may reflect the overall status of women in a society and a larger culture of gender-based violence (GBV) in both peace and war. An exclusive focus on CRSV overlooks violence against women in the private sphere (Gray 2019; Kirby Reference Kirby2015; McWilliams and Ni Aolain Reference McWilliams and Ni Aolain2014). This article explores the link between local conflict violence and individual women's experiences of intimate partner violence. Building on the feminist notion that “the personal is political,” I problematize how violence committed in the “public sphere” is more readily acknowledged, while the connections between women's experiences of violence in “private” and larger sociopolitical structures are made invisible.

GBV is a global problem of pandemic proportions (Devries et al. Reference Devries2013). It is a severe violation of women's integrity and rights, with great population health costs (Heise Reference Heise1994). GBV is associated with unintended pregnancy and abortion (Gomez Reference Gomez2011; Pallitto et al. Reference Pallitto2013), contraceptive nonuse (Svallfors and Billingsley Reference Svallfors and Billingsley2019), self-reported ill health (Ellsberg et al. Reference Ellsberg2008), suicidal thoughts and attempts (Devries et al. Reference Devries2011; Ellsberg et al. Reference Ellsberg2008), and societal gender equality (Heise and Kotsadam Reference Heise and Kotsadam2015; Yodanis Reference Yodanis2004). Hence, understanding GBV during war is a matter of recognizing human security beyond armed groups and how different forms of violence are interlinked. It also adds to our comprehension of how contextual factors such as exposure to violent conflict shape lives, social relations, and the risk of gendered violence at the micro level.

The term “gender-based violence” illustrates violence related to hierarchies between sociobiologically ascribed categories such as gender. It is manifested in many forms, such as rape, sexual assault and exploitation, child and forced marriage, and forced contraception, abortion, and adoption. I use the term “intimate partner violence” and its abbreviation IPV here since the analyses are restricted to this form because of the lack of information on men's and gender minorities’ victimization and violence against women by other perpetrators.

This study builds on a small body of quantitative research in which women's exposure to local conflict has been linked to a higher risk of experiencing IPV at the population level (La Mattina Reference La Mattina2017; Østby Reference Østby2016; Østby, Leiby, and Nordås Reference Østby, Leiby and Nordås2019; Rieckmann Reference Rieckmann2014).Footnote 1 Compared with previous studies on Colombia (Rieckmann Reference Rieckmann2014), I use monthly instead of yearly conflict data and disentangle different forms of IPV. This enables more precision in the analysis of the timing of violence and facilitates a better understanding of the complexities of violence that women may face. I propose a systematic framework of multiple micro- and macro-level mechanisms by which conflict could be associated with a higher risk of IPV. The article also contributes with novel analyses of how conflict exacerbates women's victimization by reducing their likelihood of leaving violent relationships.

Colombia is a particularly interesting case for studying the relationship between conflict and IPV. First, the peace process, with its unique gender focus, provides a moment of opportunity for research and policy efforts targeting GBV in all its diversities. Insights from this study can inform prevention programs and transitional justice interventions in Colombia and beyond. Second, Colombia has had a uniquely long-term conflict with large variation across space and time in violence intensity (Bergquist, Peñaranda, and Sánchez Reference Bergquist, Peñaranda and Sánchez G2001). Third, unlike most humanitarian settings, long-term, high-quality, nationally representative data are available on the prevalence of IPV (DHS 2005, 2011, 2017).

MECHANISMS AND PROXIMATE DETERMINANTS OF INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE IN ARMED CONFLICT

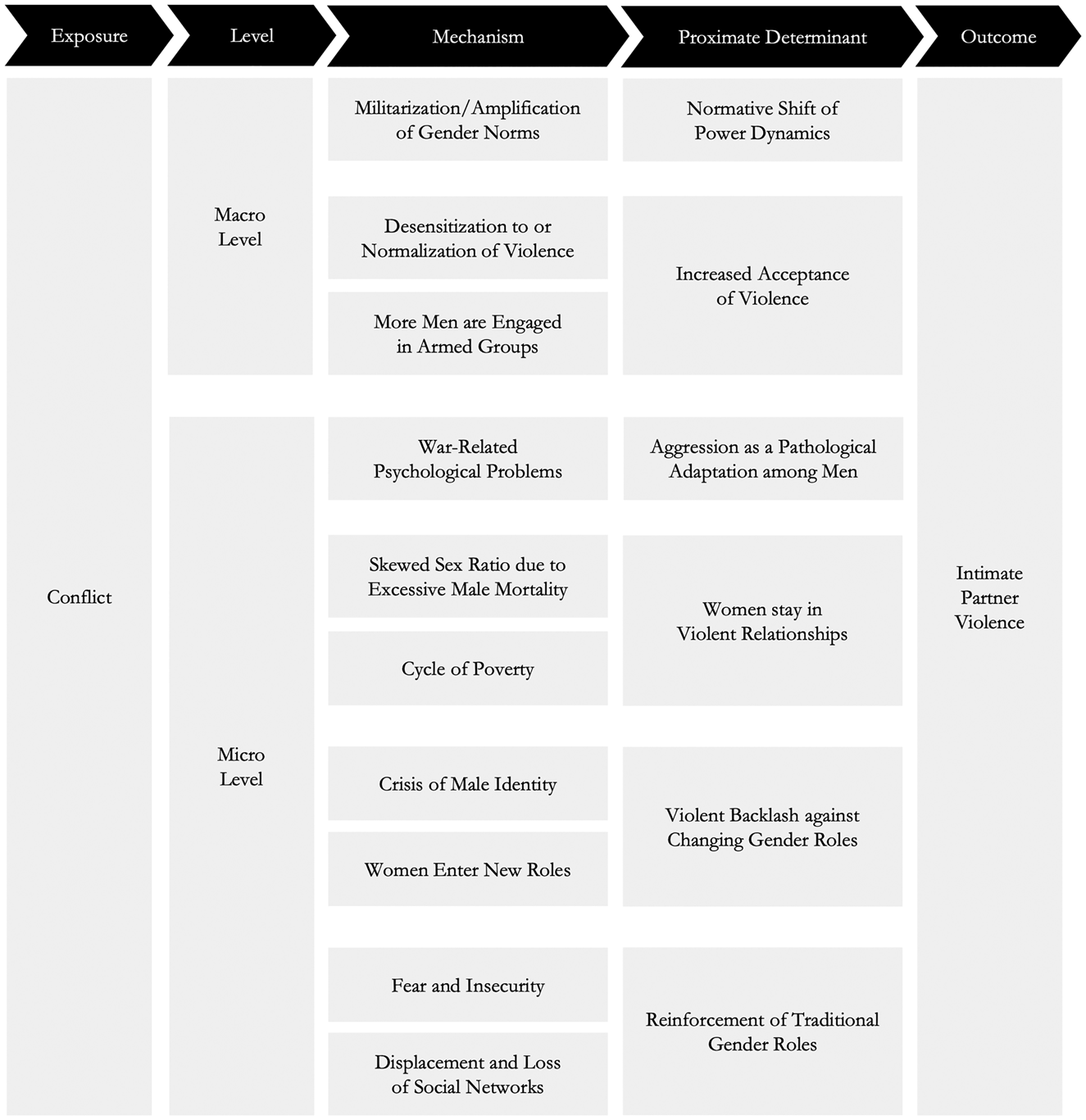

I propose a systematic framework that operates on the macro and micro levels to explain how conflict may spill over into relationships in a way that could affect women's risk of experiencing violence, as illustrated in Figure 1. On the macro level, conflict may shape the dynamics of a society or a community in a way that undermines women's safety. On the micro level, conflict may have effects on relationships and individuals that enable violence against women. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and are perhaps mutually enforcing (Müller and Tranchant Reference Müller and Tranchant2019). The hypothesis is that exposure to conflict is associated with a higher probability of being exposed to IPV.

Figure 1. Mechanisms between armed conflict and intimate partner violence.

Normative Shift of Power Dynamics

In societies and communities plagued by violent conflict, a normative shift of power dynamics that condones IPV in general may occur if gender norms are militarized or patriarchal attitudes are amplified. This may be particularly relevant in protracted conflicts such as that in Colombia.

Community-level gender unequal attitudes are known to drive the risk of IPV for individual women (Ackerson and Subramanian Reference Ackerson and Subramanian2008; Cools and Kotsadam Reference Cools and Kotsadam2017; Koenig, Ahmed et al. Reference Koenig, Ahmed, Hossain and Khorshed Alam Mozumder2003; Koenig et al. Reference Koenig2006; Vyas and Heise Reference Vyas and Heise2016). Scholars have argued that gender relations in war are based on preexisting gender norms, calling to attention how IPV may occur as an amplification of patriarchal attitudes and practices (Alsaba and Kapilashrami Reference Alsaba and Kapilashrami2016; Brownmiller Reference Brownmiller1976; Henry Reference Henry2016; Milillo Reference Milillo2006; Sengupta and Calo Reference Sengupta and Calo2016).

Building on Connell's (Reference Connell2002a, Reference Connell, Cockburn and Zarkov2002b; Connell and Messerschmidt Reference Connell and Messerschmidt2005) concept of hegemonic masculinity, “militarized masculinity” is a useful term to explain changes in gender norms during conflict. It identifies the soldier as hegemonic within armed groups, where militarized masculinity is socialized in profoundly male-dominated organizations. It is not a cultural constant but pervades societies and time with few exceptions because even though most men are not soldiers, most soldiers are men (Connell Reference Connell, Breines, Connell and Eide2000; Goldstein Reference Goldstein2001; Parpart and Partridge Reference Parpart, Partridge and Evans2014; Rones and Fasting Reference Rones and Fasting2017; Wadham Reference Wadham, Woodward and Duncanson2017).

Conflict may amplify patriarchal gender norms in the process of militarization, which has the capability to transform the meanings of people, things, and ideas far beyond the battlefield. The basic assumptions of militarism are that armed struggle is the best solution to conflict, human nature is prone to conflict, and men who do not participate in fighting (such as conscientious objectors) are unpatriotic and feminized (Bibbings Reference Bibbings and Carden-Coyne2012; Clark Reference Clark1946; Enloe Reference Enloe, Cockburn and Zarkov2002; Jones Reference Jones2006). Militarism and patriarchy are not inseparable, but the first tends to privilege the other by constructing both masculinity and femininity in parallel (Enloe Reference Enloe2000, 288–300) through designating the role of arms and politics to men and the role of caregiving to women (Cockburn and Zarkov Reference Cockburn and Zarkov2002). Sexual violence can be a strategy for armed groups to create social ties and socialize norms about masculinity (Cohen Reference Cohen2017). Large-scale, masculinity-affirming CRSV could increase in tandem with other forms of GBV, including IPV.

Increased Acceptance of Violence

Also at the macro level, acceptance of IPV may increase within a society or community if violence overall becomes normalized in the context of conflict and if more men engaging in armed activities creates a compositional change. This pathway, too, may be more salient in long-term conflicts.

War tends to have a desensitizing effect on the perception of violence and create a dehumanized view on victims (Annan and Brier Reference Annan and Brier2010; Wood Reference Wood2014). Increased acceptance of violence can also occur in tandem with an amplification of patriarchal norms. When men are thought of as inclined to force by nature or nurture, men's violence may be normalized and condoned regardless of whether it is committed by soldiers or civilians. Violence against women, then, may not be considered a “real” crime, as the behavior is regarded “part and parcel of being male” (Bibbings Reference Bibbings and Carden-Coyne2012, 51). Community-level IPV and homicide rates have been connected to individual risk of IPV (Koenig et al. Reference Koenig2006; McQuestion Reference McQuestion2003; Pallitto and O'Campo Reference Pallitto and O'Campo2005), perhaps reflecting a macro-level normalization.

Aggression as a Pathological Adaptation among Men

At the individual level, war trauma may cause psychosocial problems, which, in turn, may cause more IPV if men develop aggression as a pathological adaptation to a violent environment.

We can expect changes in norms and behavior among witnesses of violence in families (Pollak Reference Pollak2004) and communities. Responses to trauma tend to vary across gender, as men are more prone to develop aggression, while women are more likely to show signs of depression (Mead, Beauchaine, and Shannon Reference Mead, Beauchaine and Shannon2010; Ng-Mak et al. Reference Ng-Mak, Salzinger, Feldman and Ann Stueve2004; Schwab-Stone et al. Reference Schwab-Stone1995). Young boys and girls express emotions similarly, but they are typically socialized later to do so differently. Boys and men are often taught to suppress emotion even when faced with war atrocities, or risk shame and death. GBV may be enabled by constructing masculinity through emotional suppression to enhance men's war capabilities (Goldstein Reference Goldstein2001; Montes Reference Montes2013).

IPV is sometimes condoned as an inevitable by-product of conflict through the medicalization of war traumas that naturalize everyday militarized gender roles by portraying violent behavior as a mental illness (Gray Reference Gray2016b). Mental health disorders have been linked to both conflict (Tamayo-Agudelo and Bell Reference Tamayo-Agudelo and Bell2019) and IPV perpetration (Yu et al. Reference Yu2019). Violent behavior may be reinforced if men turn to alcohol and drugs to deal with trauma, poverty, and loss of identity; substance abuse has been consistently linked to violent abuse (Hindin, Kishor, and Ansara Reference Hindin, Kishor and Ansara2008; Kishor and Johnson Reference Kishor and Johnson2004; Koenig, Ahmed, et al. Reference Koenig and Lutalo2003; Koenig, Lutalo, et al. Reference Koenig, Ahmed, Hossain and Khorshed Alam Mozumder2003; Mootz et al. Reference Mootz2018; Sengupta and Calo Reference Sengupta and Calo2016; Yu et al. Reference Yu2019).

Women Stay in Violent Relationships

At the micro level, women's trauma and changes to relationship dynamics and socioeconomic conditions may lead to victims’ acceptance of violence and increased propensity of staying in abusive relationships (Friedemann-Sánchez and Lovaton Reference Friedemann-Sanchez and Lovaton2012). Since breaking up a violent relationship may be the time when women are most at risk of vengeful acts of violence, women could be reluctant to leave (Stanko Reference Stanko1997). Additionally, areas with high levels of conflict may have less institutional support for victimized women (Svallfors Reference Svallfors2021). Potentially, a higher frequency of IPV related to conflict could result from relationships that would otherwise have dissolved but did not, and not necessarily only from new violence in relationships that were previously free from abuse.

IPV is often theorized as a result of power dynamics (Goode Reference Goode1971; Heise Reference Heise1998) based on material, economic, and social resources in a relationship (Miedema, Shwe, and Kyaw Reference Miedema, Shwe and Kyaw2016). The relative and absolute socioeconomic status of the victim, partner, and community are often discussed as central proximate determinants of IPV (Cools and Kotsadam Reference Cools and Kotsadam2017; Friedemann-Sánchez and Lovaton Reference Friedemann-Sanchez and Lovaton2012; Svec and Andic Reference Svec and Andic2018; Vyas and Heise Reference Vyas and Heise2016; Yount Reference Yount2005). Women with better resources may be more able to leave an abusive relationship as well as conflict areas, and conflict-induced poverty could hinder women from staying safe.

In war contexts, being “a good man” often means taking up arms to protect the family. Choosing a partner who is engaged in an armed group can be a protection measure, putting women at risk of “domestication” of violence (Theidon Reference Theidon2009). Women may stay in an abusive relationship if excessive male mortality in conflict creates a skewed sex ratio, with fewer prospects of forming a new relationship (Jones and Ferguson Reference Jones and Ferguson2006; La Mattina Reference La Mattina2017). La Mattina (Reference La Mattina2017) found that women were no more accepting of IPV to explain their increased victimization, but trauma may lower their self-esteem (Carlton-Ford, Ender, and Tabatabai Reference Carlton-Ford, Ender and Tabatabai2008) and make them less avoidant of harm (Mead, Beauchaine, and Shannon Reference Mead, Beauchaine and Shannon2010) without changing normative beliefs.

Violent Backlash against Changing Gender Roles

Given how conflict disrupts the social fabric and reorganizes resources, gender dynamics are likely to shift at multiple levels. Men may exercise IPV as a control instrument if conflict changes gender roles within couples—for example, if men lose labor market opportunities or if women enter new economic and political roles.

IPV has been discussed as a violent backlash against women's decision-making or resource attainment challenging hegemonic male breadwinner norms (Burazeri et al. Reference Burazeri2005; Cools and Kotsadam Reference Cools and Kotsadam2017; Gupta et al. Reference Gupta2009; Heise and Kotsadam Reference Heise and Kotsadam2015; Hindin and Adair Reference Hindin and Adair2002; Tenkorang Reference Tenkorang2018). This could occur in conflict as a result of the upheaval of social structures—for example, if development programs focus explicitly on women's empowerment (Sengupta and Calo Reference Sengupta and Calo2016) or if more women become heads of household and main breadwinners in places where this is culturally uncommon (Meertens and Segura-Escobar Reference Meertens and Segura-Escobar1996; Rajasingham-Senanayake Reference Rajasingham-Senanayake2004). Women who organize in their communities may be especially at risk, by simultaneously challenging the gendered division of labor and norms about female respectability (Enloe Reference Enloe2000, 126–31).

Reinforcement of Traditional Gender Roles

During conflict, gender dynamics within couples may revert back to a traditional division between men as empowered and women as disempowered because of fear, insecurity, and displacement.

In a context with narrowly defined masculinity, insecurity can lead men to grasp for control in any way they can, such as becoming more dominant in a partnership. This operates in the same way as the backlash mechanism presented earlier (see also Jones and Ferguson Reference Jones and Ferguson2009).

Displacement often causes new vulnerabilities for women because of the disruption of social networks that are sources of social control and checks on behavior that could protect them from harm, among other things. Precarity following displacement often forces women into sex work or domestic work under slave-like circumstances as the only available way to make a living (Meertens Reference Meertens2001a, Reference Meertens, Bergquist, Peñaranda and Sánchez G2001b; Meertens and Segura-Escobar Reference Meertens and Segura-Escobar1996; Mootz et al. Reference Mootz2019; Osorio Pérez Reference Pérez and Edilma2008; Wirtz et al. Reference Wirtz2014). Hence, displacement may put women at risk of IPV. However, Friedemann-Sánchez and Lovaton (Reference Friedemann-Sanchez and Lovaton2012) found that conflict-induced migration was associated with reduced risk of physical IPV, perhaps indicating that leaving communities where violence is normalized liberates women from harm. Insecurity may also push women into narrowly defined roles emphasizing their femininity (Connell Reference Connell2002a), including the need for male protection, which may be linked to women's reluctance or inability to leave violent relationships as described earlier.

GENDERED COMPLEXITIES OF VIOLENCE IN COLOMBIA

The Colombian armed conflict ignited in the mid-1960s as a surge of left-wing guerrillas tried to influence policy by means of arms. The conflict's roots lie in the country's colonial heritage and core issues such as unequal land ownership, labor conditions, state elitism and bipartisanship, and a substantive democratic deficiency. Actors involved in the fighting include the Colombian government, left-wing guerrillas such as FARC and ELN (National Liberation Force), right-wing paramilitary groups, and organized crime cartels. Over the decades, the war has mutated into even more complex logics, linked to the privatization and impunity of violent crimes; tactical assassinations of politicians, journalists, and human rights defenders; and the trade of illicit drugs and arms. Narcotrafficking has been a perpetual fuel for conflict according to the political economy of the global cocaine trade (Bergquist, Peñaranda, and Sánchez Reference Bergquist, Peñaranda and Sánchez G2001; Jansson Reference Jansson2008).

The lives of most Colombians have been spent under violence, which has had multifaceted and gendered consequences. For young men, homicides have been the principal cause of death, and taking up arms has been a way to escape precariousness in a country with tremendously uneven resource distribution. Women, contrarily, have more often been the primary targets of widespread sexual violence and displacement, not least following the murder of a partner (Franco et al. Reference Franco2006; Garfield and Llanten Morales Reference Garfield and Llanten Morales2004; Meertens Reference Meertens2001a, Reference Meertens, Bergquist, Peñaranda and Sánchez G2001b; Meertens and Segura-Escobar Reference Meertens and Segura-Escobar1996; Mootz et al. Reference Mootz2019; Osorio Pérez Reference Pérez and Edilma2008; Wirtz et al. Reference Wirtz2014).

Sexual violence against women has been perpetrated by all armed groups in Colombia. It has been used purposefully to intimidate individuals and communities, extract information, humiliate and hurt enemies, enforce strict rules of conduct, and punish allegiances, transgressions of traditional gender roles, and civil society activism (Kreft Reference Kreft2019, Reference Kreft2020; Meertens Reference Meertens1995, Reference Meertens2001a, Reference Meertens, Bergquist, Peñaranda and Sánchez G2001b; Meertens and Segura-Escobar Reference Meertens and Segura-Escobar1996; Theidon Reference Theidon2009). Sexual violence has been one of the main drivers of women's displacement, which has further exacerbated their vulnerability. Women have often not considered themselves victims and have generally avoided reporting violations in fear of reprisals and stigmatization. The government has allowed a system of impunity surrounding these crimes. It is impossible to say how prevalent this phenomenon has been, but Afro-Colombian and indigenous women in rural areas have been disproportionally affected according to a discriminatory nexus of gender, ethnicity and precarity. Combining these factors, sexual violence has been normalized (Kreft Reference Kreft2019, Reference Kreft2020; Meertens Reference Meertens1995, Reference Meertens2001a, Reference Meertens, Bergquist, Peñaranda and Sánchez G2001b; Meertens and Segura-Escobar Reference Meertens and Segura-Escobar1996; Theidon Reference Theidon2009). There have been multiple efforts to end the Colombian armed conflict over the decades. The current peace and reconciliation process that disarmed the largest guerrilla, FARC, has uniquely focused on gender. The gender provisions included, among other things, ensuring women's right to land ownership, integrating a gender approach into the mandate of the Truth Commission and organizing special hearings for women, and excluding sexual violence from amnesty in the process of transitional justice (Salvesen and Nylander Reference Salvesen and Nylander2017).

EMPIRICAL APPROACH

Two sets of data are combined to account for women's experiences of conflict and partner violence. The Colombian Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) offer nationally representative indicators for experiences of and attitudes toward IPV from 2005, 2010, and 2015. Data were pooled to increase statistical power. To correctly observe women's exposure to conflict and avoid self-selection out of “treatment,” the sample is restricted to women who did not move from one municipality to another during the time when conflict was observed because there is no information about the location of their previous residence. Estimates were robust to including women who relocated (available upon request). The sample selection consists of 76,692 or 66,760 women who did not relocate in the past year or five years respectively, are aged 13–49, and have ever been in a union, as those are the women who were asked about their experiences of IPV.Footnote 2 Response rates were over 86% in all rounds (DHS 2005, 2011, 2017).

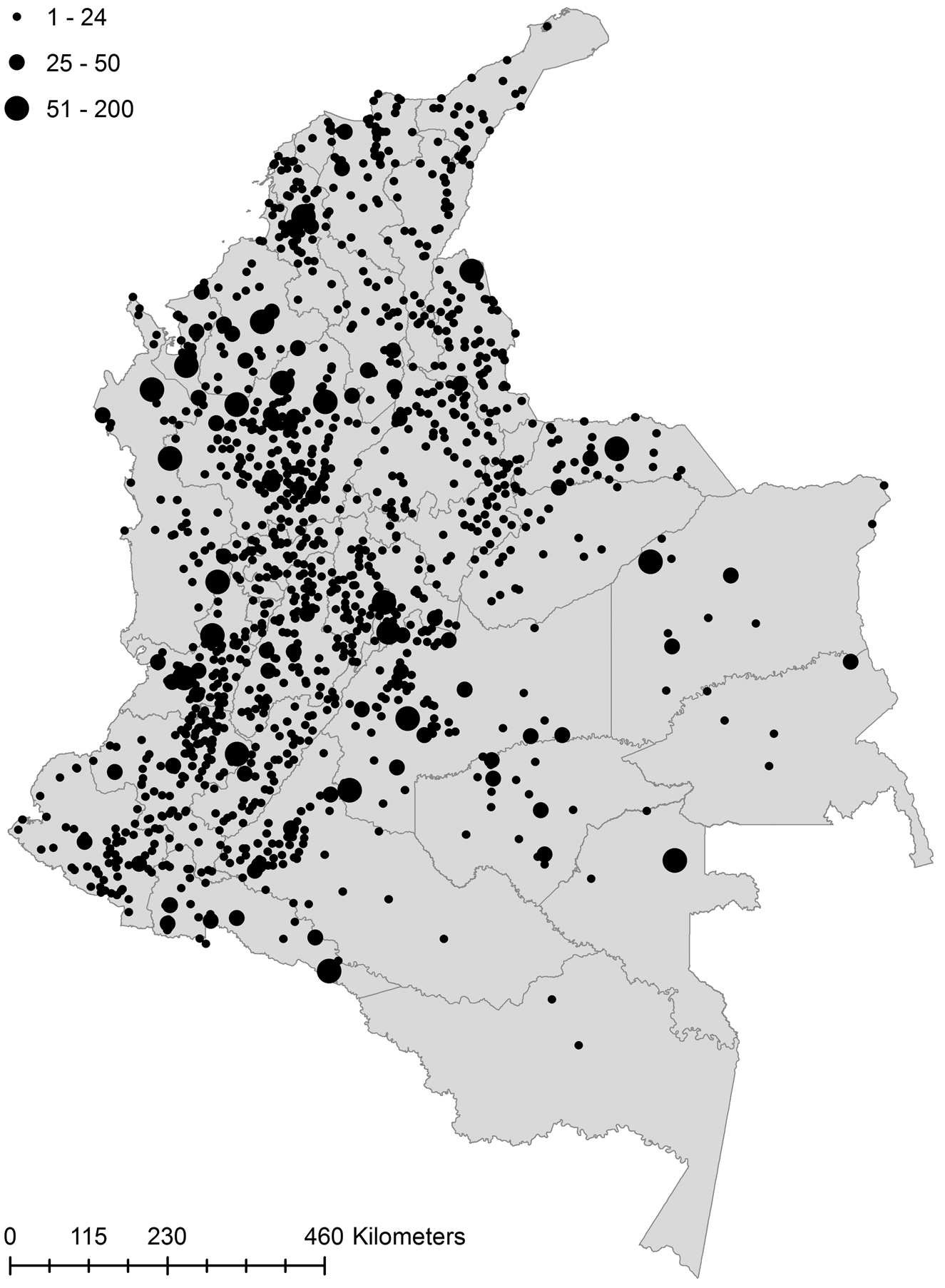

The Uppsala Conflict Data Program's Georeferenced Event Data measure each event of organized violence in which at least one person was killed, based on global and local media, reports, books, and so on. It includes information on when and where the event happened and the number of deaths in each event (Croicu and Sundberg Reference Croicu and Sundberg2018; Sundberg and Melander Reference Sundberg and Melander2013). The intensity of conflict in Colombia is illustrated in Figure 2; each bubble indicates an event of conflict, and larger bubbles indicate more casualties in the event.

Figure 2. Prevalence of conflict events across Colombia, 1989–2016.

Because of the longevity of war in Colombia, no pre-post comparison is possible. Instead, the extensive variation in conflict violence intensity across time and space is used to test the relationship between conflict and IPV. The data sets are combined in multiple ways to enable comparisons of estimates and model fit for different measures of conflict. Events and deaths of violent conflict are merged with observations of individual women according to different time frames (one, three, or five years before IPV based on monthly information about when the interviews and events of violence occurred) and location (municipalities or departments, i.e., administrative subdivisionsFootnote 3).

Method

I use linear probability models (LPMs) to estimate the probability that a certain outcome will occur using a linear combination of effects of independent variables.

Since assignment to “treatment” is not randomized in Colombia but stratified across sociogeographic factors, the method used must consider variation within country subdivisions. Fixed effects and robust standard errors compensate for local omitted factors that could codetermine IPV and armed conflict. This allows the baseline risk of IPV to vary across clusters and uses variation within clusters over time to generate estimates in a multilevel structure (Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2009; Stock and Watson Reference Stock and Watson2008). The cluster variable department indicates which of Colombia's 33 departments the respondent lived in at the time of the interview. The range of sampled respondents in each department varied from 1,542 in Guainía to 5,259 in Antioquia.

Dependent Variables

Four items and indices provided in the DHS are included to measure women's experiences of IPV in the previous year. Experiences of IPV ever in one's lifetime are not included, since it is not possible to ascertain when the violence occurred.

Emotional violence is a composite measure of whether the respondent's (ex-)partner was jealous if she talked to other men, accused her of unfaithfulness, did not permit her to meet female friends, tried to limit contact with her family, insisted on knowing where she was, did not trust her with money, ignored or did not address her, did not request her opinion for family or social gatherings and on important family matters (Cronbach's α = 0.81).

Physical violence indicates whether the respondent's (ex-)partner had pushed, shook, thrown something at, slapped, punched, or hit her (α = 0.75).

Severe physical violence captures whether the respondent's (ex-)partner had kicked, dragged, strangled, or burned her or threatened or attacked her with a knife, gun, or other weapon (α = 0.71).

Sexual violence measures whether the respondent's (ex-)partner had physically forced her into having unwanted sex.

Acceptance of violence combines five items of whether the respondent answered affirmatively to considering IPV justified in any of the following situations: if a woman goes out without telling her husband, neglects the children, argues with her husband, refuses to have sex with him, or burns the food (α = 0.64). The indicators were only available for the survey rounds conducted in 2010 and 2015. Never-partnered women were excluded for consistency with other dependent variables.

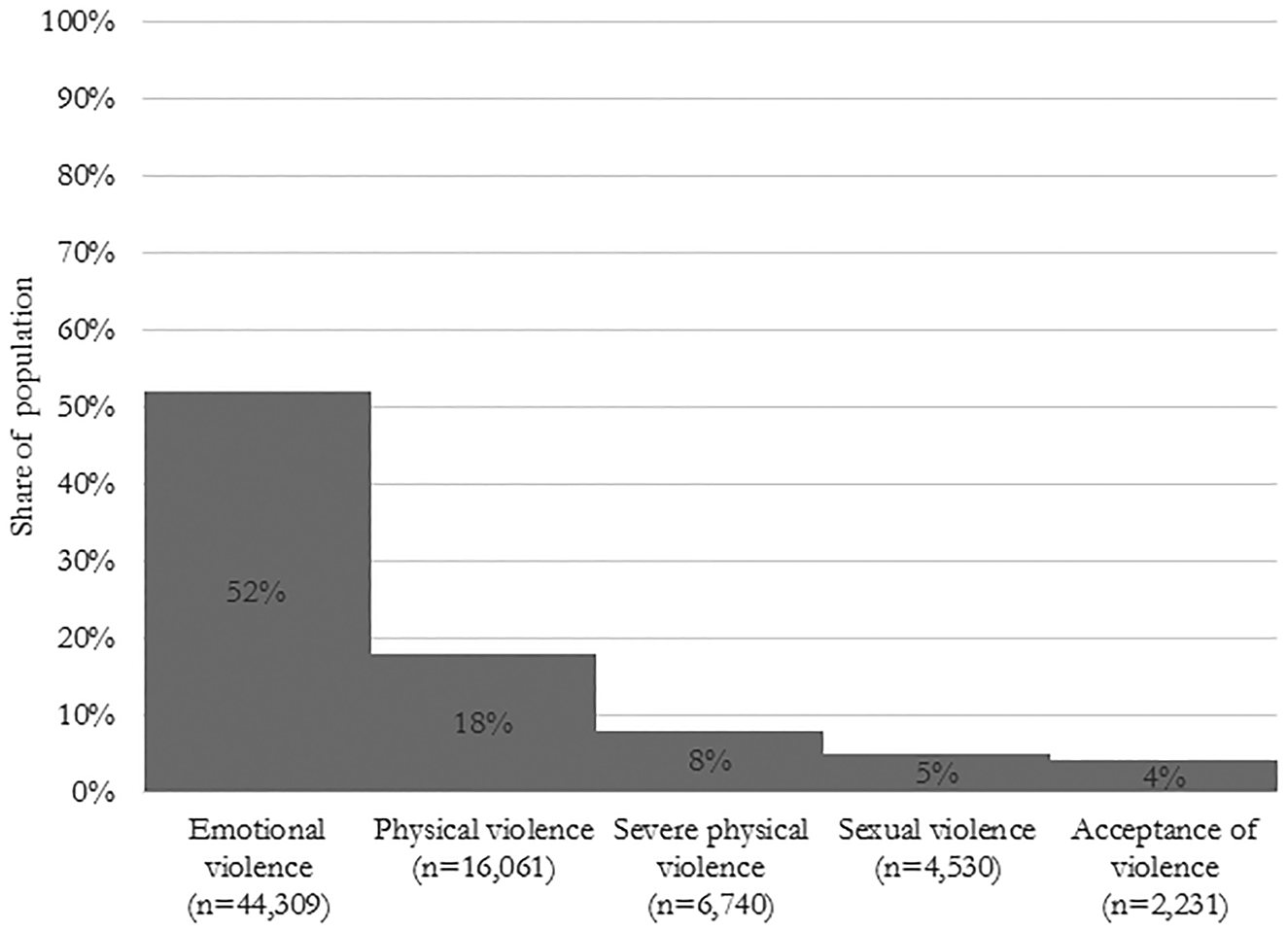

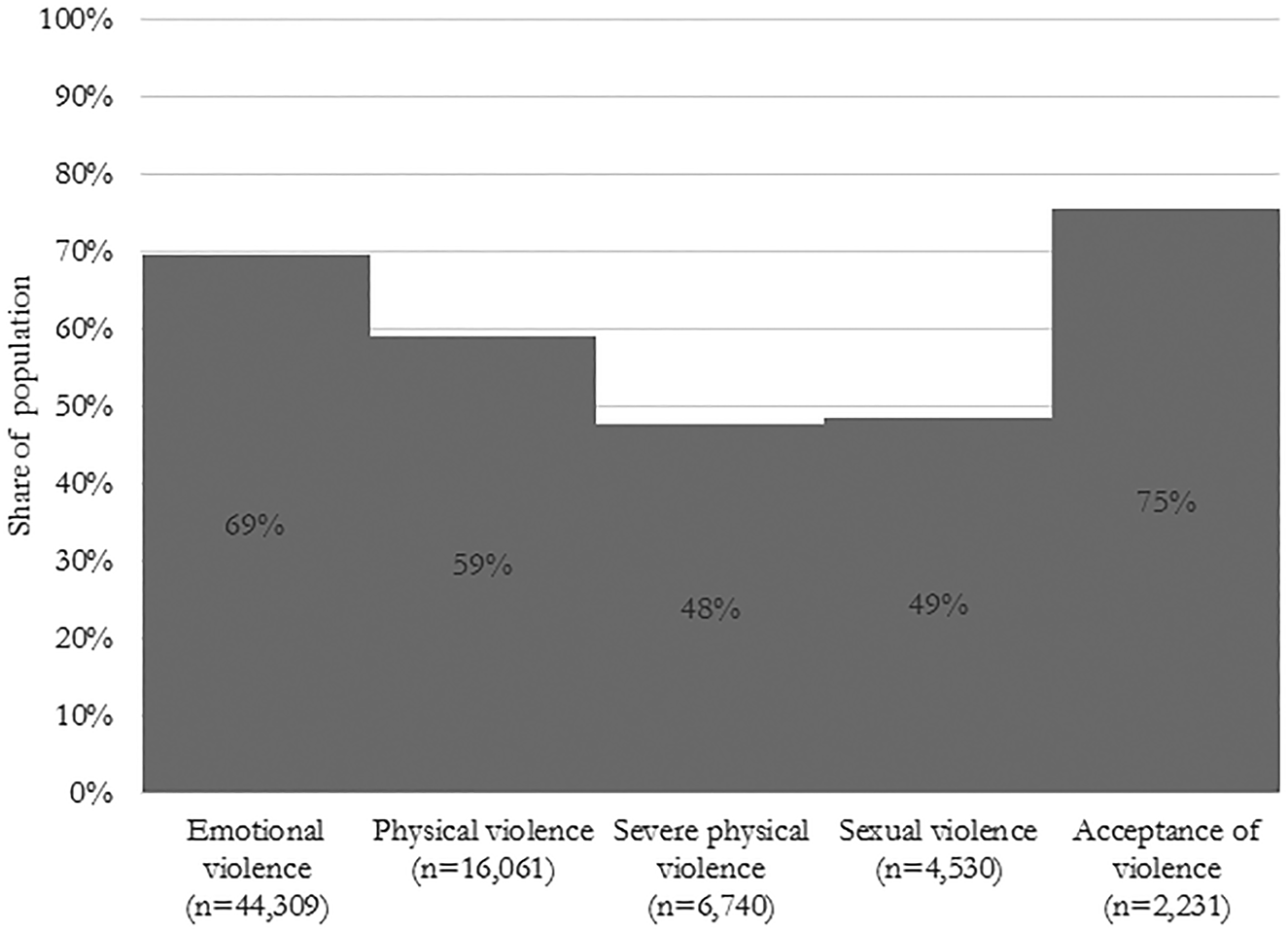

Descriptive statistics of the dependent variables measuring experiences and acceptance of IPV in the sample population are presented in Figure 3. There is a gradient in prevalence as more than 50% of the population had experienced emotional violence, 20% physical violence, 8% severe physical violence, and 5% sexual violence.

Figure 3. Distribution in sample of women who experienced or accepted IPV.

To explore whether women who experience IPV remain in relationships, an additional dependent variable measures whether women were partnered and co-residing at interview. Figure 4 displays the shares of those who had experienced the four forms of IPV in the past year or expressed acceptance of violence that were partnered at interview. A larger proportion were partnered among those who experienced emotional or physical violence, while around half the women who had experienced severe physical or sexual violence were partnered at interview. Among those who reported acceptance of IPV, three-quarters were partnered.

Figure 4. The share of women who were partnered at interview among women who reported experiences or acceptance of IPV in the past year.

Focal Independent Variables

Numerous specifications of conflict were tested using Akaike's information criterion (AIC) to assess where, how, and when conflict contributes most to model fit. The geographic scope of conflict was compared at the municipality and department levels. The functional form of the relationships between conflict and outcomes was explored comparing linear, dummy, and categorical measures of the conflict intensity. The temporality of the relationships was evaluated by comparing exposure to conflict during the past one, three, and five years, to see whether conflict has a more direct or more long-term impact. Finally, I tested whether conflict measured as number of battle deaths or events contributed more to model fit.

Four distinct conflict indicators were chosen based on AIC: linear measures of number of events in the past year or past five years in the department where the respondent resided at interview. Other specifications (municipality-level, binary or three-year indicators, or linear measures of number of deaths) did not contribute as much to model fit. R 2 values did not vary depending on which conflict indicator was used.

Control Variables

I control for sociodemographic characteristics that may stratify the risk of conflict and IPV. Survey round accounts for period effects. Age groups account for life-course differences.Footnote 4 Partner status measures whether respondent is partnered and co-residing, partnered but not co-residing, widowed, or divorced/separated at time of interview. The respondent's highest level of education is included because women with better educational and economic resources may have better chances of leaving abusive relationships as well as conflict-affected areas.Footnote 5 Residence captures whether the respondent lived in a rural or urban area at interview. If the respondent's father ever beat her mother is indicated in the variable family violence.

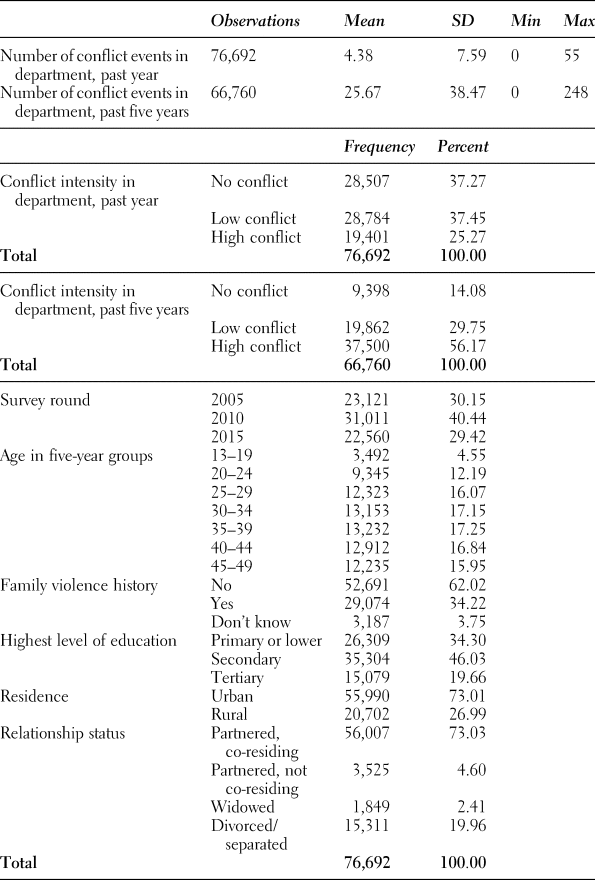

Descriptive statistics of the study population are displayed in Table 1. Here it is evident that Colombia has had substantial variations in conflict intensity across space and time, as 37% and 14% of the sample population had not been exposed to conflict in the past year or past five years, respectively.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the sample population

Note: Sample statistics for control variables are displayed for women who did not change residence in the past year.

Limitations

Because the available data do not allow for an analysis of the frequency of IPV during the past year, this study treated IPV as a certain characteristic of a relationship. Even though the DHS applies the World Health Organization's gold standard for researching IPV, more nuanced measures could improve our understanding of the intensity of partner violence. A related limitation stems from how exposure to conflict is operationalized in this and similar studies; there is no information about how women were personally affected by conflict or perceived the ongoing violence. There is also no information about whether the perpetrator of violence, her (ex-)partner, was involved in military activities or had himself been victimized. In other words, rather than personal trauma the analysis focuses on location-specific exposure, which is—for better and for worse—less subjective.

Since conflict exposure is measured within a department, the distance to each event for individual women varies. Women who live near unit borders may be equally or more affected by events in neighboring departments than by events further away in the same department.

Even if women's conflict exposure is only observed at their current place of residence, women are probably less likely to disclose shorter moves and returns, conflict-induced or not. The analyses are limited by lack of detailed data on women's migration histories, but the main results are robust to a subset of never-movers (available upon request).

Relationship status is included because it is an important confounder for who is at risk of IPV. It is only possible to know what relationship status women had at the time of interview, not at conflict or IPV exposure, both of which may affect relationship status. This limitation is mitigated by the IPV measure also including former partners. Overall, the conclusions do not change when excluding relationship status (available upon request) from the models. Partner's characteristics (such as alcohol consumption) were not available in all survey rounds and therefore were not included.

Any analysis of health outcomes in conflict is prone to survivorship bias. Displaced women, who are particularly vulnerable to GBV in multiple forms, including IPV, are probably not represented. The analyses suffer from underreporting both of IPV, both because of fear and because women who died from IPV cannot give their accounts, and of armed conflict as a result of remoteness and media fatigue. The estimates reported here should be read as floor effects, since we could expect the prevalence of both conflict and IPV to be larger.

RESULTS

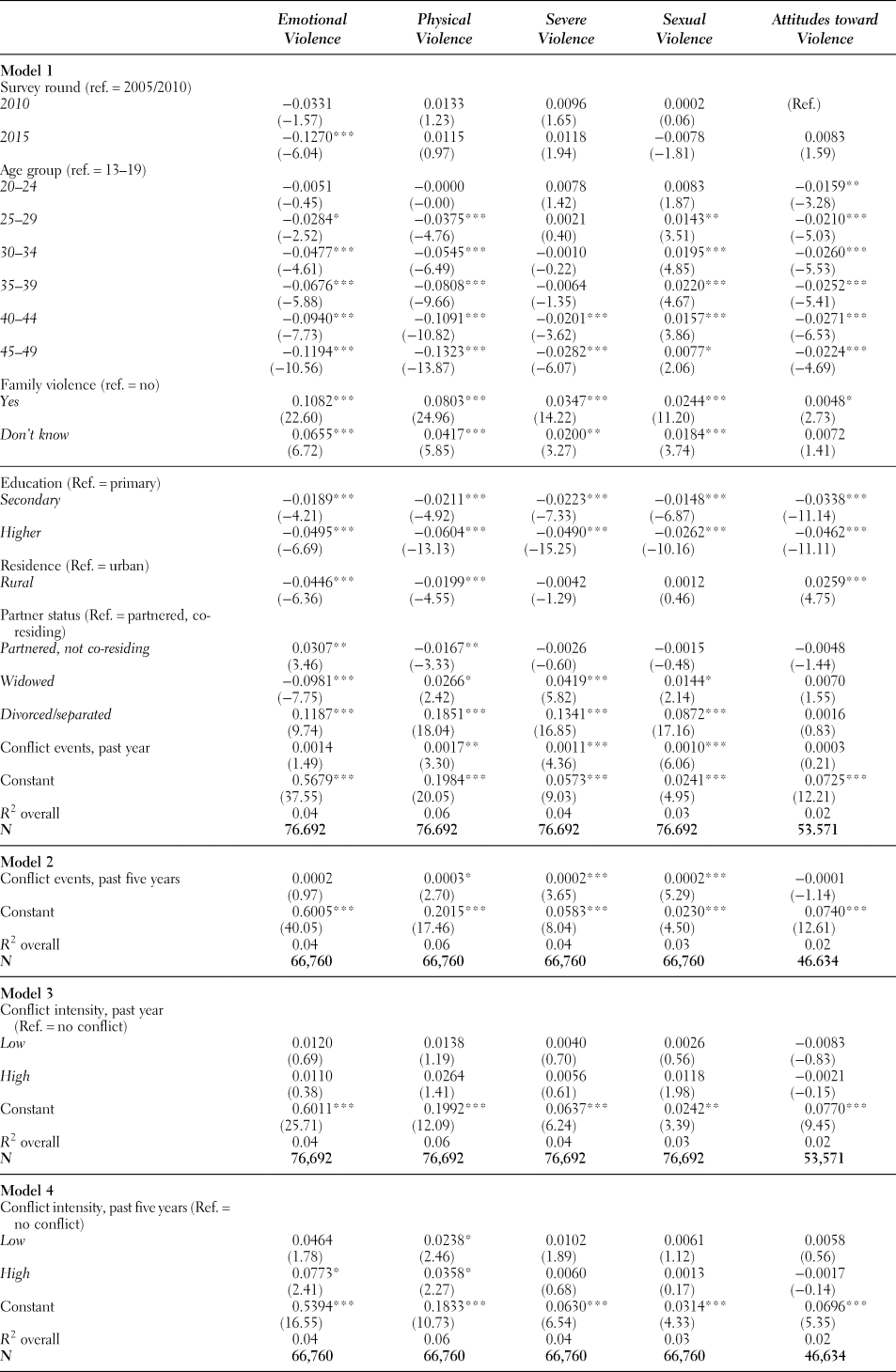

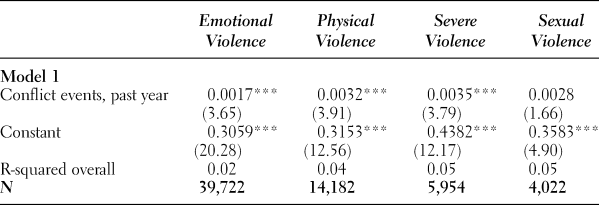

Table 2 displays the results of the department fixed-effects LPMs. Each outcome is presented in four models with distinct conflict indicators, to assess whether the impact of conflict on IPV is more immediate or long term and whether the functional form of the relationship is linear or categorical. Findings are adjusted by survey year, age, family violence, highest level of education, residence, and partner status at interview. Estimates of control variables are displayed only for Model 1, as they varied little to not at all across the models. AIC and additional full model results are available upon request.

Table 2. Department-fixed effects linear probabilities (and t-values) of women's experiences of and attitudes toward intimate partner violence in relation to local conflict violence in Colombia

Note: Models 2–4 are adjusted for survey round, age, family violence, education, residence, and partner status.

* p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001, ref. = reference.

The estimates for the linear conflict indicators show that for each conflict event, the probability of physical, severe physical, and sexual violence is slightly elevated, in Model 1 by around 0.1 percentage points in the past year and in Model 2 by 0.02 points in the past five years. This indicates that the immediate impact of war on IPV is stronger compared with the long term. Emotional violence and acceptance of violence do not have a statistically significant relationship to linear measurements of conflict.

In Model 3, when conflict is measured categorically in the past year and in reference to women who were not exposed, none of the estimates are statistically significant, suggesting that this functional form of conflict indicator is not as relevant as linear measures. In Model 4, if exposed to the highest level of conflict in the past five years, women face an 8-point increase in probability of emotional IPV and a 4-point increase of physical violence. Women exposed to low conflict in the past five years have a 2-point increase in probability of experiencing physical IPV. The other levels are not statistically significant, again pointing away from this functional form.

These findings suggest that there is a persistent relationship between conflict and emotional, physical, severe physical, and sexual IPV. Attitudes toward violence do not have a statistically significant relationship in any of the models, even when including never-partnered women (available upon request). The linear measure of events in the past year is used for subsequent analyses since it appears to be most relevant.

Only the statistically significant relationships of control variables in Model 1 will be discussed in the rest of this section.

The probability of emotional violence is 13 percentage points lower for women interviewed 2015, but there is no evidence of other period effects in IPV. Older age generally protects women from all forms of IPV except sexual violence, which may be partially explained by the decrease in acceptance of violence across the life course. It also indicates that emotional and physical IPV start early during the stages of family formation. However, this finding should be treated with caution since the reference group—13- to 19-year-old women and girls who have already formed their first partnership—is probably highly selective. Severe violence does not decrease until women are in their late 40s. Sexual violence is 1 or 2 percentage points more likely among women above age 25 compared with the youngest women.

If the respondent reports a history of family violence—that her father hit her mother—she is more likely to experience any form of and be more accepting of IPV. Those who do not know about family violence are also more likely to experience IPV, but it is not possible to interpret what this category actually represents.

As expected, those with higher education are less exposed to and less accepting of IPV. Urban residence connects to a lower risk of emotional and physical violence, which may result from reporting bias, a crisis of masculinity when faced with modern city values, or protective social control in rural areas. Rural women are more likely to report acceptance to IPV.

Compared with those living with their partner at interview, women who are not co-residing are slightly more at risk of emotional violence and at lower risk of physical violence. Widows are more at risk of physical, severe physical, and sexual violence but at lower risk of emotional violence. Being divorced or separated consistently and substantially relates to higher risk of IPV, which may reflect women ending violent relationships or facing a violent backlash as revenge after a break-up. Since there is no information about which relationships IPV occurred in, it is difficult to conclusively interpret these findings.

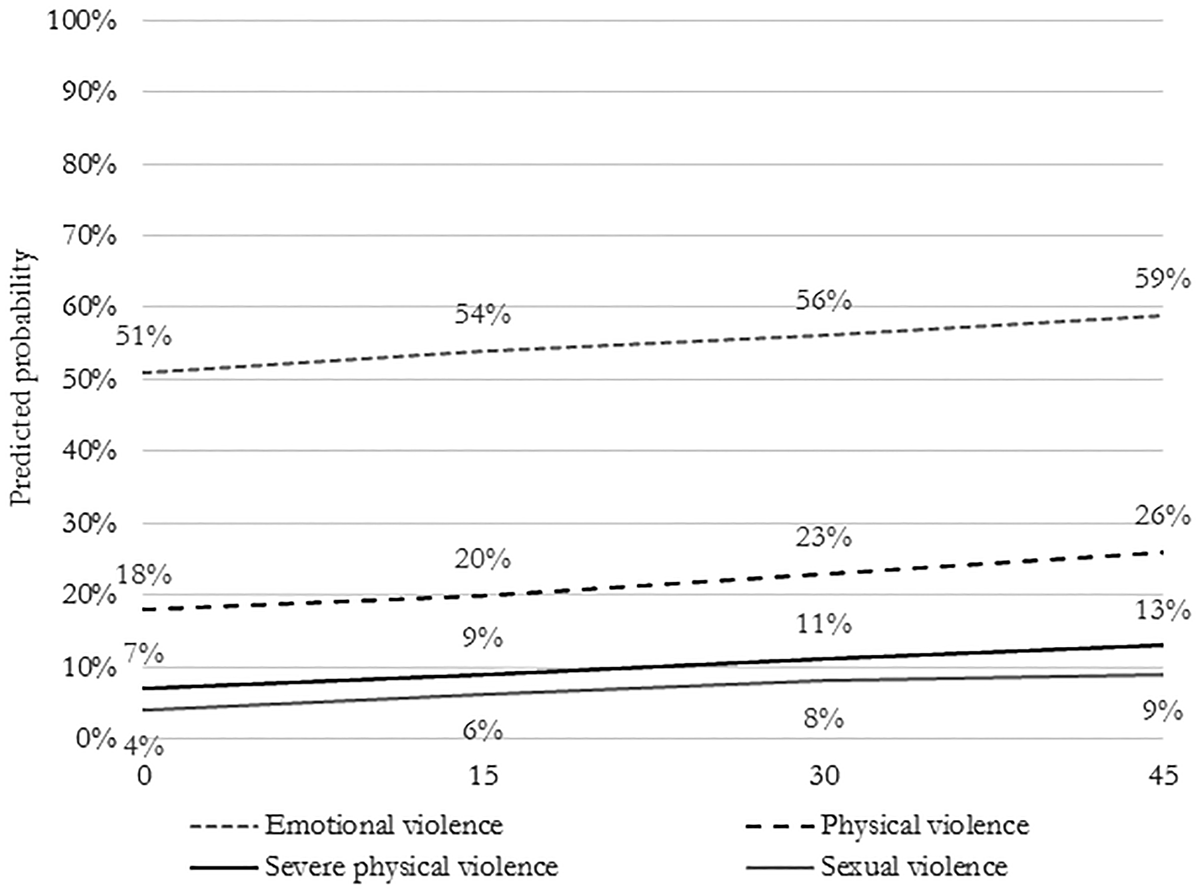

Figure 5 shows predicted probabilities to contextualize the strength of the relationship at different levels of local conflict violence intensity, using the linear indicator of conflict in the past year. Results are adjusted by survey round, age, history of family violence, education level, and partner status. Since accepting attitudes toward IPV were not related to conflict in any model, those marginal effects are not reported.

Figure 5. Predicted probabilities of IPV according to conflict events in the past year.

Across the number of conflict events in the past year, women's probability of IPV increased by 8, 8, 6, and 5 percentage points for emotional, physical, severe physical, and sexual violence, respectively. While these effect sizes are rather small, they still represent many more women facing experiences that are extremely harmful to their well-being, and the social consequences of these offenses cannot be minimized. Severe physical and sexual violence increase the most relative to their prevalence: the probability doubles at the highest intensity of conflict observed.

Since the form of GBV analyzed here is perpetrated by women's current or former partner, a closer analysis of whether women are more likely to stay in abusive relationships because of conflict is useful to understand their risk of victimization. Among women who experienced emotional, physical, and severe physical IPV in the past year, local conflict was associated with a higher probability of being partnered at interview, as displayed in Table 3. Women who reported sexual violence were not more likely to be partnered at interview as a result of conflict. Findings are adjusted for survey round, age, history of family violence, education, and residence. When exploring the same relationship among women who did not report IPV, for a counterfactual check, no such pattern presented itself. For them, some of the linear conflict measures were negatively associated with the probability of being in a relationship at interview, but most relationship statuses were not statistically significant (available upon request). Possible interpretations of these findings are discussed in the next section.

Table 3. Department-fixed effects linear probabilities (and t-values) of being partnered at interview in relation to local conflict violence in Colombia, among women who reported four forms of IPV in the past year

p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001, adjusted for survey round, age, family violence, education, and residence.

DISCUSSION

This article has shown that exposure to events of armed conflict is generally linked to an elevated risk for women of experiencing emotional, physical, and sexual violence perpetrated by their intimate partners. Since even small increases in IPV represent many more women facing experiences that are extremely harmful to their well-being, the social significance of these results cannot be minimized. Given that violent conflict and experiences of IPV are both likely underreported, it is probable that the reported estimates represent floor—not true—effects.

The results confirm those from previous studies on IPV at the population level in armed conflict (La Mattina Reference La Mattina2017; Østby Reference Østby2016; Østby, Leiby, and Nordås Reference Østby, Leiby and Nordås2019; Rieckmann Reference Rieckmann2014), while using temporally fine-grained measures of conflict and disentangling different forms of IPV. As evidenced here, violence at the meso and micro levels are indeed interconnected: exposure to violence in the local context constitutes a risk factor of IPV for individual women. This confirms previous scholarship on how gender and violence are connected on a continuum from the international to the personal (Cockburn Reference Cockburn, Giles and Hyndman2004). According to this study, the associations were strongest for the graver forms of violence, which could suggest that the normalization of violence in all its forms intensifies with conflict. The short-term impact of conflict was stronger than the long-term impact.

Like La Mattina (Reference La Mattina2017), there is no evidence that conflict is linked to women's increased acceptance of IPV. However, those items were only available in the two latest survey rounds and had little variation (only 4% of women reported accepting attitudes). The null results in relation to conflict could stem from low statistical power rather than a true zero effect. Scholars have raised concerns that it is unclear whether the DHS items measuring acceptance of IPV reflect respondents’ own beliefs or perceptions of the social norm in their setting (Perrin et al. Reference Perrin2019; Schuler, Lenzi, and Yount Reference Schuler, Lenzi and Yount2011; Tsai et al. Reference Tsai2017).

The article also contributes with novel analyses of women's relationships, by showing a positive relationship between conflict and the probability of being partnered at interview among victimized women. This could reflect a normalization of violence that makes women stay in abusive relationships, possibly driven by changes in collective norms. If women are under the impression that IPV is a legitimate behavior or they have themselves to blame, they may not end a violent relationship (Stanko Reference Stanko1997). It could also reflect a reluctance among women to leave those relationships because of increased insecurity, need for protection, and worse economic prospects due to war.

Both results could be true, if women are no more normatively accepting of IPV but remain in violent partnerships because they accept victimization and are less harm avoiding because of trauma (Mead, Beauchaine, and Shannon Reference Mead, Beauchaine and Shannon2010) or perceive they are unable to leave because of heightened insecurity. Given the limitations of the composite acceptance measure, it is difficult to conclusively say how these contrasting findings harmonize. But regardless of why women stay in abusive relationships, it is highly troubling if conflict cements their victimization. These findings could suggest that armed conflict not only is indirectly extremely harmful to women by increasing their risk of multiple forms of IPV, but also exacerbates the vulnerability of women who are already victimized.

The key policy implication from this article is that the focus in the Havana Peace Accord of 2017 on sexual violence was not enough to address all forms of GBV in the Colombian armed conflict. The increased attention to women's wartime experiences, not least of sexual violence, constitutes a big victory for the Colombian women's rights movement and sets the standard for peace and reconciliation processes to come. Still, a sole focus on “public” violence overlooks the hidden casualties from war in the private sphere. The classic feminist notion that “the personal is political” is useful to explain how violence committed in the “public sphere” (i.e., when it has political underpinnings or when the perpetrator is a stranger) is more readily acknowledged. The connections between women's experiences of violence in “private” and larger sociopolitical structures are made invisible, even if that violence is more frequent and sometimes more traumatic because of its intimate connotations (Skjelsbæk Reference Skjelsbæk2006). Relying on dichotomies of violence—such as battlefront/homefront, extraordinary/everyday, or public/private—risks leading to simplistic understandings with limited capacity to improve the lives of people living in war zones (Browne et al. Reference Browne2019; Gray Reference Gray2016a, Reference Gray2019; Kirby Reference Kirby2015; McWilliams and Ni Aolain Reference McWilliams and Ni Aolain2014). If the goal of peace initiatives is a positive peace, without any forms of physical and structural violence that could be causes of future conflict (Cockburn Reference Cockburn, Giles and Hyndman2004; Galtung Reference Galtung1969), violence in intimate partnerships must be addressed alongside sexualized aggressions perpetrated by armed groups. These insights into IPV during war as a human security issue beyond armed groups can inform prevention programs and transitional justice interventions.

The upheavals inherent in civil war and its reparations can open opportunities for change, such as gains in women's political representation (Anderson and Swiss Reference Anderson and Swiss2014; Webster, Chen, and Beardsley Reference Webster, Chen and Beardsley2019) and new gender relations that replace traditional norms (Connell and Messerschmidt Reference Connell and Messerschmidt2005). In Colombia, sexual violence against women and the feminization of internal displacement have provided a space for women's agency and new social roles (Cadena-Camargo et al. Reference Cadena-Camargo, Krumeich, Duque-Páramo and Horstman2019; Kreft Reference Kreft2019; Meertens Reference Meertens2001a; Osorio Pérez Reference Pérez and Edilma2008). Colombia is now at a watershed moment of societal transformation with an ongoing peace process that is uniquely focused on gender equality. Although much work remains to be done, this represents an unprecedented opportunity for addressing GBV in all its forms, including IPV.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLICY

It is imperative that the government and international development cooperation in Colombia introduce comprehensive GBV primary prevention programs to facilitate change by addressing the underlying root causes of violence. These bodies must also develop careful survivor response systems to address the consequences of GBV and avoid re-traumatization: specialized health services including, but not limited to, trauma counseling and sexual and reproductive care, legal support for victims, as well as training and capacity building for professionals in the health system and law enforcement. Both primary and secondary prevention should include economic empowerment that would enable women to leave abusive relationships. Involving women-led civil society organizations on the ground and listening to women and girls is essential. Since conditions vary significantly throughout Colombia, community-level engagement allows for discussions with key stakeholders and tailoring culturally sensitive and effective programs for the specific setting, without compromising on human rights. Finally, this endeavor demands fully implementing the Havana Peace Accords, above all with respect to its gender provisions.