INTRODUCTION

This paper examines the political implications of the criminal justice system for those who experience it indirectly: the friends and extended families of individuals who become caught up in the criminal justice system through heightened police surveillance, arrest, probation/parole and incarceration, which scholars have termed “custodial citizenship” (Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014, 8). Contact with the criminal justice system is increasingly common in the United States, which incarcerates more of its citizens than any other western democracy (West, Sabol, and Greenman Reference West, Sabol and Greenman2010). In addition to the 2.3 million people currently behind bars scholars estimate that more than 19 million have a felony (Uggen, Manza, and Thompson Reference Uggen, Manza and Thompson2006). Fully 23% of Black adults have a criminal background, and Latinos make up 50% of federal inmates, highlighting extreme racial disparities in American criminal justice (Meissner et al. Reference Meissner, Kerwin, Chishti and Bergeron2013). A growing body of research explores the impact of criminal justice contact on political participation finding that depressed voter turnout is the result whether one has been incarcerated, arrested, or lives in a high-contact community (Burch Reference Burch2011, Reference Burch2013; Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014).

For every custodial citizen there is a network of additional individuals learning civic lessons by watching the criminal justice system in action via a loved one. Approximately 44% of Black women and 32% of Black men, compared to 12% of white women and 6% of white men, currently have a family member in prisonFootnote 1 (Lee et al. Reference Lee, McCormick, Hicken and Wildeman2015). This paper therefore moves beyond custodial citizenship to focus on the political effects of proximal or vicarious criminal justice contact. Scholars define proximal or vicarious contact as having a loved one who is a custodial citizen without yourself having had contact (Rosenbaum et al. Reference Rosenbaum, Schuck, Costello and Hawkins2005; Stoudt, Fine, and Fox Reference Stoudt, Fine and Fox2011; Walker Reference Walker2014).

The families of custodial citizens are key sources of support, interacting with and navigating the criminal justice system on behalf of their loved ones. Given that men are incarcerated at a rate of 1,352 per 100,000 in the population compared to a rate of 126 among women, gender is an important moderator of the impacts of proximal contact (Wagner Reference Wagner2012). Likewise, proximal contact introduces a host of policy issues of special import to women of color since contact is racialized (Smooth Reference Smooth2006, Reference Smooth2011). Exploring this dynamic, Smooth writes about a representative of an urban district who asserted criminal justice as a women's issue:

She explained that the high incarceration rates among black men in her district contributed exponentially to the number of single, female-headed households, many of which faced economic challenges without the financial support of a partner … She also cited the financial toll exacted on women who are disproportionately responsible for the support and care of an incarcerated family member … For all of these reasons, she determined criminal justice to be concretely in the interest of women in particular (2011, 436).

The intersection of gender and race is therefore a key analytical frame for understanding the political implications of proximal contact. Heeding the call of critical race scholars to consider the mutually constitutive experiences of race and gender, we specifically examine the role of proximal contact in shaping the participation of Black women and Latinas as political actors (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Hancock Reference Hancock2003; Harris-Perry Reference Harris-Perry2011; Sampaio Reference Sampaio2004).

Scholarship on the participation of black and brown women has long found that traditional resource models of participation do not explain their behavior, identifying social capital, strong social networks, and community trust as more salient predictors of their participation (Brown Reference Brown2014; Cole and Stewart Reference Cole and Stewart1996; Farris and Holman Reference Farris and Holman2014; Jones-Correa Reference Jones-Correa1998; Pantoja and Gershon Reference Pantoja and Gershon2006; Smooth Reference Smooth2011). Ethnographic work finds that for women mobilizing in their communities around issues related to poverty, political participation is viewed as a natural extension of care work (Naples Reference Naples1998). For some immigrant women, leveraging their roles as caregivers provides a pathway out of the home and into politics (García-Castañon Reference García-Castañon2013; Jones-Correa Reference Jones-Correa1998; Kondo Reference Kondo2012; Sampaio Reference Sampaio2004). Through this research, intersectional scholars reconstruct women's function as “caregiver,”Footnote 2 which codes the civic and political behavior of women of color out of politics and into the private realm of the “family,” as explicitly political (Fraser Reference Fraser1997). We build on this insight and apply it specifically to the participatory reactions to proximal contact of women of color.

The repercussions of proximal contact include reduced trust, antigovernment sentiment, and eroded socioeconomic opportunity (Baer et al. Reference Baer, Bhati, Brooks, Castro, Lavigne, Mallik-Kane, Naser, Osborne, Roman, Roman, Rossman, Solomon, Visher and Winterfeld2006; Clear Reference Clear2007; Johnson and Easterling Reference Johnson and Easterling2012; Western and Wildeman Reference Western and Wildeman2009). Day-to-day family responsibilities are placed on women left behind as chief economic providers and caregivers, often under the additional burden of heightened surveillance by a state that sees them as criminally affiliated (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw2012). At the same time, proximal contact introduces an additional need to care for the custodial loved one. Advocating for those caught up in the system is a natural extension of this care, leading women to navigate a labyrinth of policy and bureaucracy (Smooth Reference Smooth2006, Reference Smooth2011).

We argue that, for women contending with the negative effects of the criminal justice system, caregiving that results from proximal contact becomes linked to political (productive) labor. When caregiving is viewed this way, proximal contact is a catalyst for political action. Participation manifests in reaction to eroded trust in government but a continued commitment to family and community. This provides motivation to participate and situates the family and caregiving as intertwined with the civic life and political agency of those left behind. Proximal contact should have special implications for women of color, whose families and communities are disproportionately targeted and degraded by criminal justice intervention. Lastly, we argue that participation resulting from experiences with the system is often non-electoral, eluding traditional models of voting but affirming the bridge between caregiving and politics. Our theory, that proximal criminal justice experiences can spur political engagement, diverges from much existing research on the political consequences of the carceral state. This work largely finds that negative carceral experiences alienate and demobilize. We draw on critical race and feminist scholarship, which constructs caregiving as political, to identify a path to mobilization among those with proximal contact.

Following intersectional analysis that leverages “categories of difference that influence how people live their lives, interact socially, and access political power” to quantitatively evaluate the political implications of the social constructs of race and gender, we test our theory by drawing on a nationally representative survey collected in 2013 (Farris and Holman Reference Farris and Holman2014, 334). These data are unique in the criminal justice literature in that they measure proximal contact together with traditional measures of participation and include a nonwhite oversample. Moreover, where others have leveraged ethnographic data to suggest that women with incarcerated loved ones become politically engaged through the experience, we are the first to test this proposition quantitatively (Gilmore Reference Gilmore2007; Lee, Porter and Comfort Reference Lee, Porter and Comfort2014). Likewise, where considerable attention has been paid to the racialized effects of the criminal justice system, this analysis uses an intersectional lens to evaluate the extant effects of the carceral state.

We find support for our claim that proximal contact with the criminal justice system increases one's likelihood of participation in nonvoting activities. This finding holds among women, but not men, and the size of the effect is largest and only significant among women of color. Black women and Latinas are more likely to know intimately multiple people caught up in the criminal justice system, and the saturation of their networks with custodial citizens heightens the political salience of proximal contact in ways absent for their white, female counterparts. Through this analysis we combat the erasure of women of color in the power structures that govern their families and communities (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw2012). Through Crenshaw's reframing of questions of mass incarceration around the unique experiences of women of color, we identify conditions under which negative experiences with the system may mobilize: caregiving that arises from proximal contact is a catalyst to political action.

RELEVANT LITERATURE

Political Participation among Women of Color

A small body of research examining the intersection of race and gender and political participation supports the theory that proximal contact catalyzes action among women of color through their traditional roles as caregivers (Brown Reference Brown2014; Farris and Holman Reference Farris and Holman2014; Naples Reference Naples1998; Simien Reference Simien2004). Studies suggest that nonwhite women participate at higher levels than both non-white men and white women (Giddings Reference Giddings1984; Harris Reference Harris1999; Harris, Sinclair-Chapman, and McKenzie Reference Harris, Sinclair-Chapman and McKenzie2005; Robnett Reference Robnett1997). This finding confounds the standard resource model of participation, where socioeconomic status should depress participation among women of color. Harris, Sinclair-Chapman and McKenzie write, “Black women are often grassroots organizers of political, community and religious organizations though they may be less directly engaged in campaign activities,” highlighting that the SES model of participation speaks most closely to voting, where women engage in a variety of ways beyond the ballot box (2006, 1150; Van Slyke and Eschholz Reference Van Slyke and Eschholz2002). Naples notes that women engaging in their communities around the issue of poverty describe it as a shared sense of caregiving (Naples Reference Naples1998). She writes:

Most of the resident community workers viewed both their unpaid and paid work as caretaking or nurturing work despite the radical political activities involved. Their involvement in social protests, public speaking, and advocacy as well as grant writing, budgeting, and other administrative tasks were viewed as a part of a larger struggle—namely doing “just what needed to be done” to secure economic and social justice for their communities (1998, 129).

Thus, caregiving, coded as unproductive labor under gendered norms, is actually veiled political labor and motivates engagement in a variety of political activities beyond voting.

Literature on the mobilization of immigrant women offers further evidence of the caregiving thesis (García-Castañon Reference García-Castañon2013; Jones-Correa Reference Jones-Correa1998). Caregiving becomes an accessible and safe avenue for entry into American political society, allowing immigrant women a chance to learn about politics and engage with political institutions at their own pace (García-Castañon Reference García-Castañon2013). Jones-Correa (Reference Jones-Correa1998) finds that rather than participating in immigrant organizations where their role may be limited due to gendered power dynamics, immigrant women turn to more traditional avenues, mapping otherwise “nonpolitical” behaviors like caregiving onto more traditional acts. Participation in order to better serve their communities becomes the language of engagement, rather than simple interest or skill. These authors show that this negotiation between gendered expectations of immigrant women and their desire for political growth illustrates that caregiving can provide cover for political engagement.

Caregiving as a gendered task and identity extends across racial categories (Cole and Stewart Reference Cole and Stewart1996). Indeed, early work on gender indicates that participation was highest among all women when they felt connected to their communities, were empowered, and wanted to create change, across all races. As an institutional intervention into their lives and communities, however, the criminal justice system racializes the politicization of caregiving as a pathway to participation. For communities targeted by law enforcement, the carceral state constitutes a threatening policy environment for community members to navigate daily. Research demonstrates that communities facing threats from punitive and targeted policies self-defensive mobilize (Barreto and Woods Reference Barreto, Woods, Segura and Bowler2005; Pantoja, Ramirez, and Segura Reference Pantoja, Ramirez and Segura2001; Pantoja and Segura Reference Pantoja and Segura2003; Parker Reference Parker2009a, Reference Parker2009b).

By explicitly linking the “unproductive” labor of caregiving to political engagement, scholars deconstruct gendered notions of politics and leadership (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Sampaio Reference Sampaio2004). For some women, this is a cover for genuine political interest, while for others it may be the opening to a longer, more complete empowerment. Either way, understanding caregiving as political work reveals important ways women engage in politics. Although the political threat literature largely focuses on the single axis of race without attention to gender, introducing criminal justice intervention as a threatening policy environment necessarily racializes caregiving as a pathway to political engagement. We leverage this intersectional dynamic when engagement is catalyzed by proximal contact with the criminal justice system, an institution that takes for granted the political power of women of color.

The Politics of Proximal Contact

Angie Marie Hancock argues that scholarship interested in race and gender dynamics must “acknowledge the persistent challenge of simultaneous privilege and disadvantage in increasingly complex ways,” complicating the additive model of intersectionality beyond being black or brown and a woman and a mother/daughter/sister/wife (2014, 292). Attending to Hancock's reproach, we explore how women bridge their various identities in service to others and in service to themselves in reference to the institutional intervention of criminal justice in their lives.Footnote 3 A recent study estimates that this institutional intervention is common, where Black women have extended family that is incarcerated at at a rate eight times greater than that of white women, and 1.5 times greater than Black men (Lee et al. Reference Lee, McCormick, Hicken and Wildeman2015).

Proximal contact confers negative personal consequences less thoroughly than does custodial citizenship, but it does result in consequences that matter in shaping the day-to-day lives of these caregivers. One suffers from living in a community with lower levels of economic vibrancy due to high incarceration or crime (Burch Reference Burch2013; Western Reference Western2006). Women with incarcerated partners suffer increased economic hardship (Baer et al. Reference Baer, Bhati, Brooks, Castro, Lavigne, Mallik-Kane, Naser, Osborne, Roman, Roman, Rossman, Solomon, Visher and Winterfeld2006). Children with an incarcerated parent suffer upheaval in their lives that potentially reduces overall life chances (Clear Reference Clear2007; Western and Wildeman Reference Western and Wildeman2009). Proximal contact increases the burden on the loved ones of those with a record, opening them up to additional surveillance by the state. Black women and Latinas additionally navigate negative constructions of themselves as greedy, undeserving, and uninvolved, further heightening both the salience of their political engagement and the struggle to have it taken seriously (Hancock Reference Hancock2003; Harris-Perry Reference Harris-Perry2011).

We argue that proximal contact can increase the extent to which black and brown women are central locations of activism in their communities. They perform the caretaking role of community and family maintenance when their loved ones are drawn into the criminal justice system. They push back on elite constructions of them and their community as deficient, contemptable, and unworthy of public compassion and aid (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Hancock Reference Hancock2003; Harris-Perry Reference Harris-Perry2011). Instead, these women engage in their own ways with a system that devalues them as persons, and their loved ones as “criminals.” Minority communities targeted for criminal justice contact are viewed through filters of individual, rather than systemic, interpretations of fault and blame. The individual black woman is responsible for the ills visited upon her, and no blame is placed on the systematic targeting of her community or her body through “race-neutral” policies that rely on “public identities” determined by racialized political judgments (Hancock Reference Hancock2003, 49).

Hypersurveillance structures, however, generate an outsized contact rate for those caught up in the broad approach of targeted racialized sweeps. Communities of color are subject to excessive contact often because of presumptions by law enforcement about black and brown criminality (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw2012). This works to catalyze Hancock's (Reference Hancock2014) intersectional identities as dynamic, where gender and race function in concert for women seeking political power through the framework of caregiving. It is not solely because these communities are predominantly black or brown that contact is high, but also because they are resource deficient, and the people left to resist are women engaged in caretaking, who themselves are perceived as uninvolved and undeserving (Hancock Reference Hancock2003). Systematic targeting of these communities occurs because of these three factors but underestimates the role of caregiving as kindling for further political action. The gendered nature of caregiving itself and the view of caregiving as apolitical “unproductive” labor emboldens such targeting with little fear of political pushback. However, detrimental proximal contact does not strip away the power of these communities to engage, and the lessons learned while navigating the criminal justice system are useful political tools.

Lee, Porter, and Comfort argue that the criminal justice system serves as a key site of political socialization for individuals with incarcerated family members. Using ethnographic research, they explore shifting political attitudes among women with incarcerated partners. They find that similar to the effects of custodial citizenship, proximal contact degrades trust in government and leads individuals to withdraw from voting (2014). Their analysis demonstrates that while interactions with the system are alienating, they also compel women to participate in other, nonvoting political activities out of a sense of care, stating “that some women see maintaining contact with their incarcerated partner as a political act” (2014, 57).

Gilmore's (Reference Gilmore2007) work on the activist group Mothers Reclaiming our Children (Mothers ROC) further demonstrates caregiving as politics among those with proximal contact.Footnote 4 In Gilmore's account, the women of Mothers ROC realized while working on behalf of their children that they faced a system fundamentally working against them. Like the women in Gilmore's work, the Black and Latina women in our study engage the criminal justice system and formal politics differently than they do local, nonvoting activities. While the institutional barriers resulting from contact may discourage electoral engagement, they nonetheless create political space for themselves in their communities and in support of the incarcerated. More recent examples, like Mothers of the Movement, the mothers of individuals killed through police action demonstrated that learning political lessons through proximal contact can lead to organizing, lobbying representatives, helping to draft legislation, and engaging political parties at conventions.

Lee, Porter, and Comfort (Reference Lee, Porter and Comfort2014) and Gilmore (Reference Gilmore2007) point to two interrelated ideas: understanding the criminal justice as a form of threat spurs political action, and this is most likely to occur when there are intimate or close ties to those affected by the criminal justice system. These women, as mothers, daughters, aunties, abuelas, sisters, and wives, bear witness to the effects of the criminal justice system on their loved ones. Their gender situates them as a caregiver, and their race makes proximal contact more likely. However, it is the intersection of their gender and their race that makes their position as caregivers particularly potent as an avenue for political action. They engage because they perceive change is possible, and because their caregiving role places them in the position of advocate for their loved ones. Proximal contact has soured their trust in the government overall, but their family and community commitments remain and in turn mobilize them to engage with a system they otherwise distrust. Caregiving provides the stakes for engagement with the system, one that is otherwise alienating to them as women of color.

THEORY AND EXPECTATIONS

This paper examines the political impact of proximal contact. We centralize Black women and Latinas, who are most often burdened with the spillover effects of the criminal justice system as key members of the support networks available to their custodial loved ones. We build on ethnographic work by Gilmore (Reference Gilmore2007) and Lee, Porter and Comfort (Reference Lee, Porter and Comfort2014), which identifies that these women become politicized through their experiences interacting with the criminal justice system on behalf of their loved ones. This process challenges the notion of caregiving as apolitical and instead situates the role of women as caregivers as a space used for political mobilization. The care work of women with proximal contact is thus a claim of agency rather than a gendered task.

While proximal contact with the criminal justice system crosscuts race and gender, we argue that Black women and Latinas are uniquely situated to mobilize as a result of their experiences. For many women, advocating for their loved ones caught up in the system is a natural extension of their role as caregivers. We expect, then, that proximal contact will be politically mobilizing for women, but not for men. Likewise, Black women and Latinas are more likely to be politicized by the criminal justice system than their white counterparts because of the lived reality that their families and communities are targeted for criminal justice intervention. Motivations for political engagement emerge from this caregiving role, often balanced against government distrust and alienation. In providing and serving their loved ones as caregivers, women navigate a complex web of policy and bureaucracy and often engage in behavior that reads as political—contacting local officials, attending community meetings, organizing, lobbying, networking, and so forth—and subsequently become political agents through what is a gendered and seemingly apolitical role.

Lastly, we expect that mobilization as a result of proximal contact with the criminal justice system will manifest primarily in nonelectoral behavior. Contrary to voting and other campaign-specific activities, nonelectoral participation, like attending community meetings or protests, speaks immediately and directly to needs and frustrations that arise from criminal justice contact and community policing. The caregiver role is centered on the locality of one's family and community, so it would most strongly manifest political engagement in these venues. The role of caregiver takes on an inherently political motivation, one that enables women to step beyond the expectations of their race and gender and become political agents in their own right.

DATA AND MODELING STRATEGY

We have theorized that women are politically mobilized by proximal contact with the criminal justice system through traditional roles that construct them as caregivers. The need to navigate the criminal justice system on the behalf of a loved one and to build up the social, economic, and political capital of their families and communities reduced by criminal justice intervention renders their depoliticized labor political. We further theorize that politicized action catalyzed by proximal contact should be of special import to women of color, whose communities are disproportionately targeted by the carceral state. We adopt the approach of McCall (Reference McCall2005) and Farris and Holman (Reference Farris and Holman2014) in order to test these two interrelated augments, which leverages both intracategorical and intercategorical comparisons to “systematically compare between mutually constitutive groups, not just within a single axis, in order to evaluate ‘relationships of inequality’” (Farris and Holman Reference Farris and Holman2014, 335).

Intracategorical analysis is limited to a single subgroup and facilitates an evaluation of the impact of proximal contact on women, for example, compared to other women. We begin by leveraging intracategorical analysis to test the independent effects of proximal contact on both electoral and nonelectoral participation among subsamples of men, women, whites, Blacks, and Latinos. Intragroup analysis has the possibility of revealing unique factors that influence the participation of women or people of color otherwise obscured by pooling them together with men or whites. However, intracategorical analysis prohibits the extent to which we can draw conclusions about the relative impact of proximal contact among women of color to their male and white counterparts. In order to examine differences across the mutually constitutive categories of race and gender, we interact proximal contact with race and gender. Leveraging interaction terms both ensures a robust n-value, lost when conducting analysis on subgroups, and facilitates intercategorical comparisons (Farris and Holman Reference Farris and Holman2014; Junn and Masuoka Reference Junn and Masuoka2013; McCall Reference McCall2005). We find that while proximal contact is positively associated with increased participation among white women, nonwhite men, and nonwhite women, it has special implications for women of color.

We draw on the National Crime and Politics Survey (NCPS) collected between October 11 and November 16, 2013. The survey is multimode, and 55% of respondents were interviewed by phone, and 45% completed the survey online. The phone survey included both a landline and cell phone sample. The sampling design stratified on race, including 409 whites, 200 Blacks and 132 Latinos (N = 741). Given that our modeling strategy examines gender and racial subgroups, we evaluate Blacks and Latinos together in order to maintain a robust nonwhite sample suitable to multivariate regression. The benefit of this approach is that we are able to evaluate hypothesized relationships with reasonable precision. The drawback is that it prevents a substantive assessment of the unique experiences of Black women compared to Latinas with the criminal justice system. However, given the inadequate attention in political science to the intersection of race and gender to political outcomes, we believe the analysis is worthwhile.

The key independent variable in the analysis is proximal contact with the criminal justice system. The survey asked the following two questions to measure proximal contact: “What about someone you know, such as a close friend or family member? Do you know someone who has been arrested, charged or questioned by the police, even if they were not guilty, excluding minor traffic stops such as speeding?” This was followed up with, “And how close would you say your relationship is with that person? Not very close, somewhat close, or very close?” The question used to measure proximal contact was adapted from a measure routinely fielded by scholars of Latino Politics to assess whether a respondent has a loved one who has faced detention or deportation for reasons related to immigration (Sanchezet al. Reference Sanchez, Vargas, Walker and Ybarra2015).

Proximal contact ranges from zero (no contact) to three (strong, proximal relationship). Fully 47% of the sample indicated that they had proximal contact, and 28% indicated that the proximal relationship was very strong. Moreover, like previous research which finds that nonwhite women's networks are highly saturated by incarceration, among our sample Black and Latino women were more likely than any other subgroup to report having a strong, proximal relationship with someone who had been arrested, charged, or questioned by the police. About 24% of white men and 27% of Black and Latino men reported having a strong relationship with someone who had contact with the police. In contrast, strong, proximal contact among women of color exceeded even their nonwhite, male counterparts by 10 percentage points, and white women by 15 percentage points (22% of white women compared to 37% of nonwhite women reported having strong, proximal contact).

The question measuring proximal contact is a low threshold for having had proximal contact with the system, where much of the scholarship used to construct our theory revolves around the incarceration of a loved one. The level of proximal contact may matter for participation, particularly when one's loved one is incarcerated, rather than having been stopped or arrested by police. However, research indicates that witnessing even low-level interactions as captured by this measure has the potential to impact political attitudes, and thus also behavior (Rosenbaum et al. Reference Rosenbaum, Schuck, Costello and Hawkins2005). This suggests that this low-threshold question is appropriately suited to measure the concept of interest. Moreover, rather than overestimating the effects of contact, the use of such a low threshold likely underestimates the effects of having a loved one who has been convicted or incarcerated on political mobilization. We therefore view any evidence generated from the use of these measures favorably for our theory.

The key dependent variables for this analysis are electoral participation and nonelectoral participation. Whether or not one is registered to vote, and whether or not one voted in the 12 months prior to the survey are used to measure electoral participation.Footnote 5 The survey included a battery of the following seven items to measure nonelectoral participation,Footnote 6 generating a 0–7 index range: (1) signed a petition, (2) attended a community event or meeting with people of your same race or ethnicity, (3) attended a political meeting, (4) joined an organization in support of a particular cause, (5) took part in a demonstration or protest, (6) written a letter or email to a politician or civil servant, or (7) donated money or raised funds for a social or political activity.Footnote 7 One-fifth of respondents indicated that they had not engaged in any of the activities in the last 12 months, and 3% indicated they had taken part in all seven activities. We model the nonelectoral participation index using Poisson regression, given that the battery is scaled and treated like count data.Footnote 8

We control for personal contact with the criminal justice system because it has the potential to depress participation and to covary with proximal contact. The survey asks whether or not individuals have personally been arrested, charged, or questioned by the police even if not guilty, and was modeled from the General Social Survey.Footnote 9 About 20% of respondents affirmed (coded as one) that they had personal contact. We additionally control for age, education, income, political knowledge, church attendance, party ID, and foreign-born status in order to address various sources of bias. Age, education, and income are expected to impact both likelihood of contact with the criminal justice system and political participation outcomes, where younger individuals with low socioeconomic status are both more likely to have contact and less likely to participate politically. Age is expected to have a curvilinear relationship with participation, where the young and the old are less likely to participate than their middle-aged counterparts. We therefore include dummy variables for each of these age groups. Political knowledge, church attendance, and strong partisanship are likely to increase political activity. Being born outside the United States is associated with less activity, and, depending on citizenship status, may impede voting.Footnote 10

ANALYSIS

We begin the analysis by examining the independent impact of proximal contact on electoral and nonelectoral participation among subgroups of men, women, whites, Blacks, and Latinos. Table 1 and Table 2 demonstrate the impact of contact on likelihood of being registered to vote and the likelihood of having voted. We anticipated that proximal contact would not impact electoral participation among any group. Overall, we find support for this claim. Interestingly, among men and whites personal contact is statistically associated with an increased likelihood of having voted. This is potentially due to method. The measure of personal contact is a low bar, where even those who were stopped by the police are included in the subsample. Second, voting is self-reported, where social desirability bias is a key factor influencing the outcome. We interpret these results with caution and turn our attention to nonelectoral participation.

Table 1. The impact of criminal justice contact on voter registration, by gender and race

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Table 2. The impact of criminal justice contact on voting, by gender and race

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The independent effect of proximal contact on nonelectoral participation among race and gender subgroups is displayed in Table 3. We expected that the mobilizing impact of proximal contact should be reflected in nonelectoral activities and that it should be most pronounced among women. Proximal contact is a positive and statistically significant predictor of participation among both the total population and all subgroups, aside from men. In addition to mobilizing women, Blacks, and Latinos, the positive effect of proximal contact holds among whites. This raises the possibility that rather than mobilizing through the politicization of one's role as caretaker where race contextualizes and increases the salience of criminal justice experiences, race carries with it an additive mechanism that also mobilizes men of color. Alternatively, that proximal contact is associated with increased participation among both whites and nonwhites is potentially driven by the participation of women, both white and nonwhite.

Table 3. The impact of criminal justice contact on nonelectoral participation, by gender and race

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

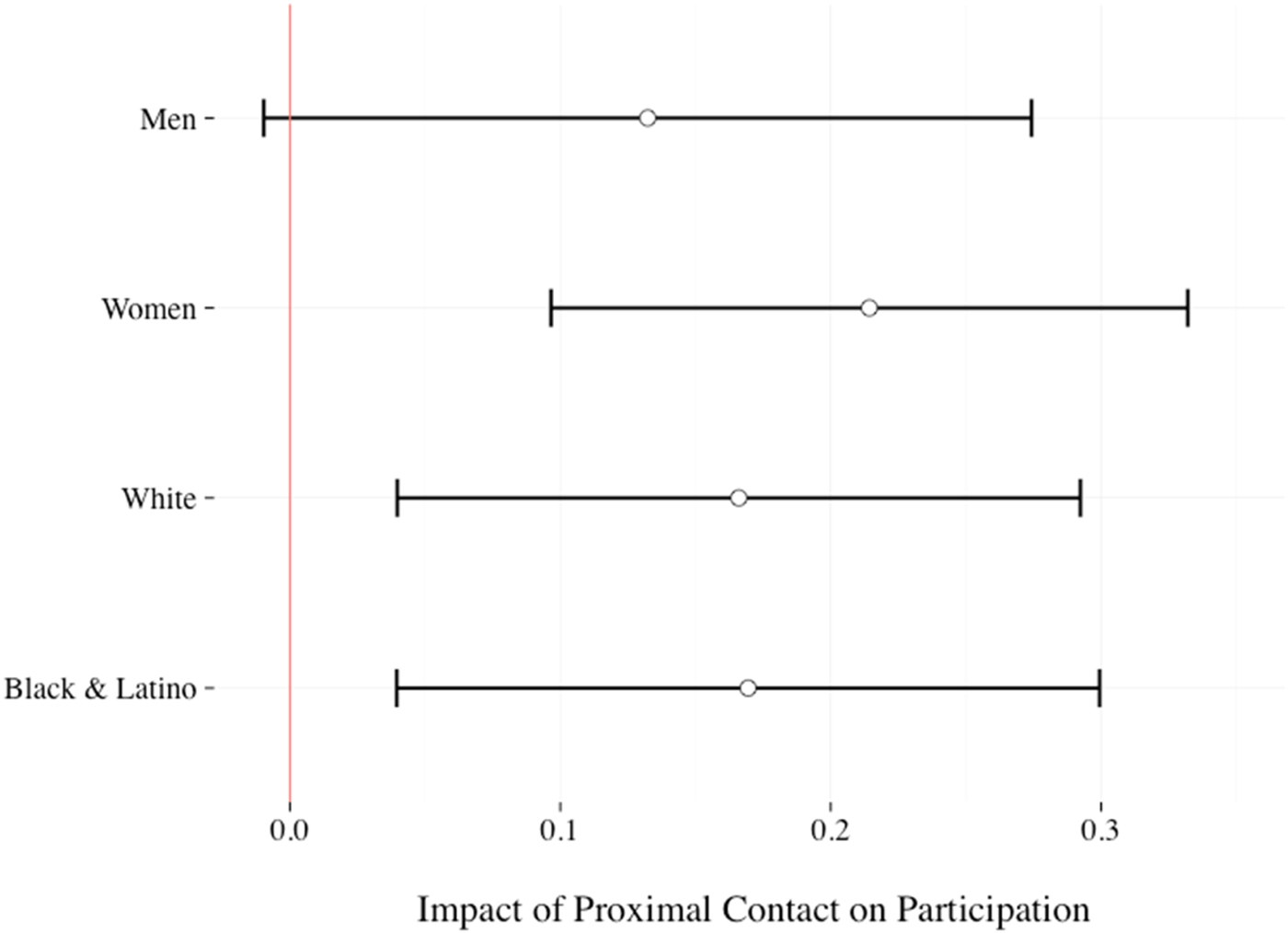

Examining the marginal effects of proximal contact among subgroups (displayed in Figure 1) offers support for the idea that the mobilization of women underlies the finding that proximal contact increases participation among both whites and nonwhites. Figure 1 displays the size of the impact of going from the minimum value of proximal contact to its maximum value on one's expected score of nonelectoral participation. When broken out by race, proximal contact increased one's score on the participation index by about .17 activities among both whites and nonwhites. Proximal contact has a differential effect among subgroups only when comparing men to women. Among men, proximal contact has a positive effect, but it does not achieve statistical significance. Among women, proximal contact increases participation by about .22 items on the index.

Figure 1. The impact of proximal contact on participation in nonvoting activities, among gender and racial subgroups.

The size of the effect of proximal contact among various subgroups appears relatively modest. Examining the marginal effects of each variable in the model compared to proximal contact facilitates an evaluation of the size of its impact. The size of the effect of proximal contact is outstripped by other variables traditionally associated with political participation, like education. However, it is comparable to the effect of high levels of political knowledge. Given that the majority of quantitative research on the impact of negative criminal justice experiences indicates we should expect proximal contact to have either no impact or a negative impact on participation, detecting any statistically significant positive effect is remarkable.

Leveraging intracategorical analysis we have demonstrated that proximal contact is associated with increased participation among women, a finding that does not hold for men. We have theorized that women are pulled into politics through their depoliticized role as caretakers and that proximal contact politicizes this labor as it maps onto traditional forms of political engagement. The preceding analysis further suggests that the mobilizing impact of proximal contact holds among both whites and nonwhites. We suspect that the mobilization of women underlies this finding, and that proximal contact has special implications for women of color.

In order to test this, we leverage intercategorical analysis through interacting proximal contact first with race and explore the interaction among men and women. We then interact proximal contact with gender and explore the interaction among whites and nonwhites. If the interaction between race and proximal contact is significant and holds among both men and women, then we might conclude that proximal contact mobilizes via the racially charged nature of experiences with the criminal justice system regardless of gender. If the interaction is significant and holds only among women, then we might conclude that proximal contact has special implications for the political participation of nonwhite women but not nonwhite men. Likewise, we interact gender and proximal contact and observe the effects among subgroups of whites and nonwhites to validate or challenge the findings derived from interacting race and proximal contact.

Table 4 displays the impact of interacting race and proximal contact. The interaction between race and proximal contact is only statistically significant among women. In order to appropriately interpret the effect of proximal contact on nonelectoral participation among white men compared to nonwhite men, white women, and nonwhite women, we derive the expected score on the nonelectoral participation index among each subgroup, displayed in Figure 2. Figure 2 demonstrates that proximal contact is positively associated with increased participation across white men, men of color, and white women. However, it is only statistically associated with increased participation among women of color, and the size of the mobilizing effect is greatest for women of color. Women of color who lack proximal contact have an expected score on the nonelectoral participation index of about 1.72. This increases to about 2.65 among those with a strong relationship with someone who has had contact with the criminal justice system. In contrast, white women with no contact have an expected score of about 2.25, which increases to 2.6 among those with a strong, proximal relationship. Strong, proximal contact increases participation by about .25 items on the index for nonwhite men and .5 items for white men. Importantly, women of color begin with an expected score on the index that is lower than all other subgroups, but strong, proximal contact closes the participation gap.

Figure 2. The interactive effect of proximal contact and race on expected value of participation in nonvoting activities, by gender and race.

Table 4. The impact of proximal contact and race on nonelectoral participation, among men and women

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Coefficients reflect fully specified models including controls for personal contact, age, education, income, political knowledge, church attendance, party identification, and foreign-born status. Full analysis can be found in the supplementary materials.

In order to validate the finding that proximal contact has special implications for the political participation of women of color we further interacted gender and proximal contact, among subgroups of whites and nonwhites. Again, cutting the data this way could reveal that mobilization extends to white women as well as nonwhite women. The results are displayed in Table 5. The mobilizing effect of proximal contact together with gender holds only among nonwhites. Exploring the expected values derived from the interaction of proximal contact and gender reveals a pattern similar to that displayed in Figure 2, where the size and significance of the impact is most relevant for Black women and Latinas.

Table 5. The impact of proximal contact and gender on nonelectoral participation, among whites and nonwhites

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Coefficients reflect fully specified models including controls for personal contact, age, education, income, political knowledge, church attendance, party identification, and foreign-born status.

Full analysis can be found in the supplementary materials.

In sum, we have argued that proximal contact with the criminal justice system has the possibility of mobilizing individuals to action. Ethnographic research suggests that for women whose communities become caught up in the system, attending to the needs of custodial citizens and advocating on their behalf is itself a form of political engagement. Building on this work, we argued that proximal contact should have special implications for the political participation of women of color. The depoliticized labor of caretaking becomes politicized through women's efforts to defend their loved ones caught up in the system. We have further argued that proximal contact should have special implications for nonwhite women whose communities are specifically targeted by criminal justice policy on the basis of race and class. Through the use of intracategorical analysis, we demonstrated that proximal contact is associated with higher levels of participation among women, but not men. Between-group comparisons further demonstrate that proximal contact is most relevant for women of color and that the size of the impact is largest for this group than for their white female and nonwhite male counterparts. The growing impact of the criminal justice system on American politics is therefore an issue of special import to women of color, and they are central locations of resistance to it.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The reach of the criminal justice system into the lives of Americans is increasingly extensive. Black men are six times more likely and Latino men are three times more likely to experience time in prison than are their white counterparts. As Black and Brown men are removed from their neighborhoods or otherwise caught up in the criminal justice system, the burden to maintain communities and to care for custodial citizens disproportionately falls to the women left behind. Thus, proximal experiences with the criminal justice system increase the caregiving demands placed on women of color. Feminist scholars identify that political action is often a natural expression of gendered care work. Women leverage their roles as caregivers, coded as apolitical and limited to the private sphere, into the public realm of politics, politicizing care work as it maps onto activities scholars recognize as political participation.

We draw on this intersectional frame to argue that proximal contact can catalyze political action. Proximal contact with the criminal justice system thrusts women into navigating a warren of administration, increases the salience of policy outcomes governing their custodial loved ones, and raises the need to defend communities degraded by criminal justice intervention. Although the political nature of care work extends to white women, the racialized nature of the criminal justice system, which targets minority communities, renders the political implications of proximal contact especially important for black women and Latinas. Lastly, we argue that women balance loss of trust in government against a commitment to community and family such that mobilization manifests in activities outside the voting booth. Drawing on a nationally representative survey we find support for our theory. Proximal contact mobilizes women but not men and is reflected in nonvoting activities. Leveraging between-group comparisons we further find that while proximal contact appears to be positively associated with participation among all subgroups, the impact is only statistically significant for women of color.

We offer these findings with several caveats, however. We have hypothesized that Black women and Latinas are uniquely impacted by targeting by the criminal justice system, but the size of the nonwhite sample prohibits an analysis of racial subgroups. The relationship between the criminal justice system and each group is potentially different in ways that may be relevant for political attitudes and behaviors. Blacks have a long, contentious history with police violence, and local policing is politically salient for the Black community regardless of gender or level of contact. While community policing is not historically a political touchstone for Latinos, police increasingly target their communities for immigration enforcement. These divergent histories highlight the need for analysis among racial subgroups and raise questions around the role of citizenship in shaping political responses to contact.

The cross-sectional, large-n nature of the data does not allow us to test directly the mechanisms linking proximal contact to participation, nor do we have measures around the precise nature of the proximal relationships respondents have to the criminal justice system. Theory would suggest that variation in severity of contact will impact participation outcomes where having an incarcerated loved one likely has a stronger mobilizing impact than simply knowing someone who was stopped on the street and questioned by the police. Likewise, having an incarcerated child or spouse is likely more highly potent than having a neighbor on probation. We test strength of relationship and find that strong proximal contact is highly mobilizing, but we are not able to explore the nature of those relationships. Lastly, there may be other mechanisms at work we are unable to test through this analysis. While caregiving is a gendered mechanism, there may be other mechanisms that interact with gender but are primarily driven by the racialized nature of the criminal justice system. The broad mobilization of Black youth around police brutality through the #BlackLivesMatter movement challenges the claim that proximal contact primarily motivates the mobilization of women of color. Thus, our analysis points to several areas for future research.

An evaluation of the impact of proximal contact on political participation and the unique role it plays in the participation of Black women and Latinas contributes to the existing literature in several important ways. Existing research on the political impacts of negative experiences with the criminal justice system overwhelmingly sends the message that all types of contact, both personal and proximal, lead to political withdrawal. Our analysis builds on a handful of works that see potential for mobilization as a result of frustrations with the criminal justice system. A few key pieces of research identify that for the loved ones of custodial citizens, caring for their family member is itself political in nature. However, this work is either ethnographic (Gilmore Reference Gilmore2007; Lee, Porter and Comfort Reference Lee, Porter and Comfort2014) or concerns the single axis of race to the neglect of gender, failing to recognize the important care work required to maintain communities, which is vital to mobilization (Walker Reference Walker2014).

Ethnographic work on the intersections of race and gender reveals a space where institutional subjugation meets resilience to produce political resistance. A focus on women of color tells us something important about the study of political engagement, which is that socioeconomic factors are limited in their ability to explain participation. To understand the mechanisms motivating participation, we must turn our attention to the institutions that create an imperative to act for people who otherwise lack the time, energy, and resources to do so. We begin with the rich theoretical and ethnographic insights in intersectional research on women of color and derive quantitatively testable propositions. We arrive at a counterintuitive answer to an increasingly important question to American politics, through classic political methodology. This analysis is the first to quantitatively test the proposition that women of color are uniquely politicized and mobilized by experiences with the criminal justice system. As such, we locate women of color as central points of resistance to the American carceral state.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X17000198.