It is well documented that women are underrepresented in politics globally, and they are even more severely disadvantaged in top political leadership positions (Bauer and Tremblay Reference Bauer and Tremblay2011; Müller and Tömmel Reference Müller and Tömmel2022). Moreover, when women do make it to the top politically, they tend to be evaluated in more negative and gender-stereotyped ways (Alexander and Andersen Reference Alexander and Andersen1993; Reyes-Housholder Reference Reyes-Housholder2020; Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2014), and they are exposed to more violence and intimidation (Håkansson Reference Håkansson2021).

To date, research on the conditions for women in political leadership positions has mainly been conducted in male-dominated contexts in which women constitute a minority (e.g., Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2009; Murray Reference Murray2010; Rai and Spary Reference Rai and Spary2019). Much of the research seeking to explain the gendered obstacles that women face in politics and political leadership within such contexts has been inspired by role congruity theory, which highlights how masculine leadership ideals clash with female gender roles to create role incongruity, resulting in prejudice and discrimination against women leaders (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). While assumptions about masculine leadership ideals likely reside on solid grounds in heavily male-dominated political contexts, the worldwide development in recent decades toward more gender-equal political representation, with an increasing percentage of women in top political leadership positions, raises new questions about the conditions for women’s political leadership.

In this article, we argue that there is a need for empirical studies of leadership ideals in gender-equal contexts, including how such ideals are connected to gendered leadership conditions more broadly. It is important to note that the degree of masculinization of leadership ideals varies across sectors, professions, and levels of hierarchy (Funk Reference Funk2019; Koenig et al. Reference Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell and Ristikari2011; Rosette and Tost Reference Rosette and Tost2010). Increasing percentages of women in political leadership thus call for theory development and empirical studies of the gendered conditions of political leadership—including both ideals and actual practices—in order to increase our understanding of when and why women political leaders face inequalities related to gender. In this regard, feminist institutional theory, which highlights how formal and informal rules, norms, and practices affect the working conditions of men and women in gendered ways, can help broaden our view of the obstacles that women face in politics (Krook and Mackay Reference Krook and Mackay2011).

For the purposes of this study, Swedish politics, and particularly the Swedish parliament, the Riksdag, constitute a suitable case. The Riksdag, which has had more than 40% women members of parliament (MPs) since the 1990s, is often described as one of the most gender-equal parliaments in the world (Freidenvall Reference Freidenvall2021). As such, it should be a relatively supportive context for women political leaders. Nonetheless, findings from previous research indicate that women face gendered obstacles even in this context (Erikson and Josefsson Reference Erikson and Josefsson2019). These multilayered findings point to the need to empirically assess a broader range of gendered practices that affect men and women leaders’ opportunities to lead on equal terms. While role congruity theory holds that masculine leadership ideals provide a key reason for negative gender biases and discrimination against women leaders in practice (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002; Schneider, Bos, and DiFilippo Reference Schneider, Bos and DiFilippo2022), a feminist institutional perspective would question the clear-cut link that has been postulated between the gendered norms of the ideal leaders and the actual (gendered) practices in a given institutional context.

Drawing on original data generated from 36 interviews conducted in 2020 with almost all the current top political leaders in the Riksdag, as well as a survey distributed to all Swedish MPs in early 2021, this study explores how conditions that shape women’s political leadership are perceived. On the basis of these data, we ask the following research questions: (1) How are leadership ideals in the Riksdag gendered? (2) Are there gender biases in the evaluation of women and men parliamentary leaders? (3) Are men and women parliamentary leaders treated equally in practice? By systematically studying three aspects of leadership conditions—ideals, evaluations, and treatment—we are able to explore how they relate to each other empirically as well as the implications that the connections between them have for theories concerning leadership and gender.

In the numerically gender-balanced context of the Riksdag, we find indications of a mainly feminine-coded parliamentary leadership ideal that emphasizes inclusion, the importance of listening, being interpersonally sensitive, and finding broad solutions. In line with role congruity theory, which maintains that there is a link between ideals and the evaluations of leaders (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002), we find that men and women leaders are, in general, evaluated equally favorably. Masculine practices nevertheless appear to remain with respect to how leaders are treated. For example, women leaders in the Riksdag are more exposed to harassment and sexism than men leaders, and their competence and authority appear to be questioned to a greater degree. We suggest that this anomaly between feminine leadership ideals and masculine practices that disadvantage women leaders can be better understood from a feminist institutionalist perspective, which provides an understanding of how gender shapes a given context in multiple ways beyond mere role congruity.

Masculine Leadership Ideals as an Obstacle for Women Political Leaders

Politics has traditionally been, and in many ways still is, a male-dominated sphere permeated by a culture of masculinity (Crawford and Pini Reference Crawford and Pini2011; Lovenduski Reference Lovenduski2005). Women entering politics—viewed as if they were “space invaders” (Puwar Reference Puwar2004)—have been confronted by this preexisting culture, and masculine-coded rules, norms, and sexist practices have tended to obstruct their political work (Lovenduski Reference Lovenduski2005). Women’s access to top political leadership positions—such as party leader, cabinet minister, and parliamentary committee chair positions—along with the possibilities they have to remain and succeed in such leadership roles, are no exceptions.

In a wide variety of male-dominated political contexts, research has found that women face greater obstacles than men, both when it comes to accessing leadership positions and in their subsequent work as political leaders. Several studies have found that aspiring women leaders are held to higher and different standards than men (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor- Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2009; Müller and Pansardi Reference Müller, Pansardi, Müller and Tömmel2022; Murray Reference Murray2010; Verge and Astudillo Reference Verge and Astudillo2019). When women do make it to top political positions, such gendered biases continue to pose obstacles for them. Women leaders generally receive less favorable evaluations, particularly in male- dominated or masculine contexts (Eagly, Makhijani, and Klonsky Reference Eagly, Makhijani and Klonsky1992). In addition, studies have revealed negative gender biases regarding how women leaders are treated in practice—for instance, women in top political positions experience more violence than men (Håkansson Reference Håkansson2021; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Herrick, Franklin, Godwin, Gnabasik and Schroedel2019). It is thus well established in existing research that women political leaders are disadvantaged in a number of different ways, which is often attributed to gender stereotypes and masculine-coded leadership ideals that undermine women’s perceived suitability and authority as top political leaders.

Eagly and Karau’s (Reference Eagly and Karau2002) role congruity theory provides a useful and widely employed point of departure for theorizing how political leadership ideals are gendered and potentially disadvantage women leaders. This theory, which proceeds from a social-psychological perspective, proposes that a perceived mismatch between the construction of the female gender role and the leadership role in historically male-dominated professions generates prejudice and discrimination against women in leadership positions (Burgess and Borgida Reference Burgess and Borgida1999; Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002; Rhode Reference Rhode2017). It is important to note that masculine attributes are also viewed as typical or ideal for leaders. This means that women who seek or hold leadership positions face a double risk of workplace discrimination—either because they are perceived as not fitting into traditionally male occupations or because they violate shared beliefs concerning how women should behave when trying to adapt to masculine leadership ideals (Burgess and Borgida Reference Burgess and Borgida1999; Rhode Reference Rhode2017, 41).

Although the generic role of a leader is associated with masculine attributes, the lack of congruence between the leadership role and the female gender role varies across contexts, sectors, and professions (Funk Reference Funk2019; Koenig et al. Reference Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell and Ristikari2011; Rosette and Tost Reference Rosette and Tost2010). When “token” women constitute a small minority in a given work setting, greater attention is drawn to their sex, and thus they tend to be viewed more stereotypically (Kanter Reference Kanter1977). Being viewed as different is expected to intensify perceived role incongruity, which increases the disadvantages women leaders face (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002, 578). In contrast, when leadership roles are perceived in less masculine terms, “they would be more congruent with the female gender role” and the prejudice against women should consequently “weaken or even disappear” (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002, 577).

On the basis of role congruity theory, we would expect that a context in which women have enjoyed high descriptive representation for a long time would have feminine-coded leadership ideals and that such ideals would, in turn, result in less role incongruity for women and more favorable conditions for women leaders in practice. While role congruity theory acknowledges the importance of a broader context to certain extent, the theory stresses masculine-coded leadership ideals as the key driver of biases and discrimination against women leaders. In contrast, feminist institutional theory (hereafter FI) argues that there is a co-constitutive relationship between a variety of gendered norms and practices within a given context. This means that although FI recognizes that (gendered) leadership ideals—norms regarding what a leader is supposed to be—are an important factor, this perspective does not attribute superior relevance to such norms for gaining an understanding of gendered obstacles in political office.

Gendered Leadership Ideals from a Feminist Institutionalist Perspective

Research conducted from an FI perspective has noted that the male norm in politics—the ideology that naturalizes and justifies men’s superiority over women—is highly institutionalized by a tradition of male dominance and that it often remains intact, at least in part, in spite of gender-equality initiatives or increases in women’s numerical representation (Kenny Reference Kenny2013; Mackay Reference Mackay2014). While the formal rules and policies that explicitly excluded women from being elected and exercising political power have been removed (Franceschet Reference Franceschet and Waylen2017, 117), unequal opportunities persist because of the “stickiness” of unwritten rules, customs, norms, and practices that favor men and masculinity (Franceschet Reference Franceschet and Waylen2017; Krook and Mackay Reference Krook and Mackay2011; Waylen Reference Waylen2014). Such informal institutions are based on shared and internalized understandings; the fact that “they are unwritten, and there are no identifiable individuals with the authority to change them” also renders it more difficult to change them (Franceschet Reference Franceschet and Waylen2017, 120).

This suggests that gender biases, including masculine leadership ideals, can prevail in spite of the presence of a large number of women leaders. Chappell and Mackay (Reference Chappell, Mackay and Waylen2017, 32) point out, however, that informal institutions do not necessarily present obstacles to gender-equality changes in the political realm since “they can also be transformative in regendering political processes and outcomes.” Furthermore, institutional arenas are constituted by a complex web of formal and informal rules, norms, and practices, and it is necessary to take into consideration the interaction that takes place between institutional features as well as the potentially disruptive or reinforcing role they can play in shaping a particular context in gendered ways (Waylen Reference Waylen and Waylen2017, 11). That is to say that although certain formal or informal rules may foster gender equality, gendered practices that undermine it may also exist.

From an FI perspective, a larger proportion of women in leading positions does not necessarily entail increasingly feminine leadership ideals and more favorable conditions for women leaders. In addition, even if leadership ideals would be more feminine in more gender- equal contexts, leading to improved role congruity for women political leaders, this might not necessarily improve the evaluation and treatment of women leaders. FI theory emphasizes that a broader range of gendered rules, norms, and practices beyond role congruity may create obstacles for women leaders. For example, masculine-coded practices and expectations of how a leader should behave in a given situation might change slower than the ideals, and thus continue to negatively influence the evaluation and treatment of women in leading positions. Likewise, sexist practices allowing for disrespectful treatment of women might prevail and influence how both men and women behave toward women leaders. In contrast with role congruity theory, FI suggests a bumpier road toward a situation in which men and women political leaders enjoy equal opportunities.

Taking these insights seriously, we suggest that FI can provide a means for gaining a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between the (gendered) institutional context, the construction of (gendered) leadership ideals, and the treatment of men and women leaders. From an FI perspective, we argue that leadership norms and practices should be viewed as both constitutive elements and products of a gendered institutional context that differs across time and place.

Gender within the Context of Swedish Politics

While male domination characterized Swedish politics during most of the twentieth century, the past three decades have been marked by great steps toward gender equality. In 1994, Sweden was the first country in the world to cross the threshold of 40% women in parliament, and this level has been maintained since then.Footnote 1 Gender equality is also a distinctive feature at the governmental level: Swedish governments have been gender balanced since the 1990s, and women have held all influential ministerial portfolios. As Annesley, Beckwith, and Franceschet (Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019, 278) note, “Sweden has initiated, confirmed and sustained a concrete floor of gender parity.”

The importance ascribed to political gender equality is further demonstrated by the fact that the Riksdag has undertaken an ambitious program of internal gender-equality work in order to improve MPs’ working conditions. A number of gender-friendly reforms have been initiated in recent decades to foster gender-equal working conditions, such as the establishment of a free childcare center in the Riksdag and fixed meeting times, including a decision to avoid late-night meetings (Erikson and Freidenvall Reference Erikson and Freidenvall2020). The Riksdag thus displays “gender sensitivity” in a number of dimensions (Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2015). In addition, a “legislative gender-equality norm” has emerged over time, demonstrated by increased support for gender equality among MPs, regardless of sex or party affiliation (Erikson and Freidenvall Reference Erikson and Freidenvall2020, 16). MPs confirm that a strong norm of gender balance in nominations and appointments to leadership positions in the Riksdag has developed since the 1990s (Erikson and Josefsson Reference Erikson and Josefsson2021). It is noteworthy that although there are no formal gender quotas in place, the proportion of women in leadership positions in the Riksdag has closely followed the proportion of women MPs during a majority of terms since 1994 (see Figure 1). The long tradition of gender balance in Swedish politics, along with the fact that Swedish democracy is characterized as a consensual system in which values that align with feminine-coded characteristics such as collaboration and consensus are emphasized, makes Sweden a most likely case for gender-equal conditions for men and women leaders.

Figure 1. Proportions of women MPs and women in Riksdag leadership positions. Leadership positions included in this graph are committee chairs, deputy committee chairs, party group leaders, and deputy party group leaders.

In spite of this, however, Swedish politics—including the Riksdag—remains a masculine-perfused context in certain ways. For example, although women MPs report that they participate in debates and influence the agenda to the same extent as men, they also experience greater pressure, higher levels of anxiety, and more negative treatment (Erikson and Josefsson Reference Erikson and Josefsson2019). There are also signs of double standards in cabinet appointments that disfavor women who behave in unfeminine ways (Baumann, Bäck, and Davidsson Reference Baumann, Bäck and Davidsson2019), as well as indications that greater merits (Bäck et al. Reference Bäck, Persson, Vernby, Wockelberg, Dowding and Dumont2009) and larger networks (Niklasson Reference Niklasson2005) are required for top women politicians than for men.

Taken together, previous research highlights that the Riksdag is an institutional context that is gendered in multiple and sometimes contradictory ways. While formal and informal rules regarding appointments to leadership positions favor men and women equally, we still know very little about how gendered norms and practices constitute and shape leadership in this numerically gender-balanced context. In spite of the vast body of literature concerning the Riksdag, to our knowledge, no work has explicitly addressed leadership ideals, neither in the Riksdag nor in Swedish politics more broadly.

Material

To analyze leadership ideals and practices in the Riksdag from a gendered perspective, this study employs a mixed-methods approach that includes both in-depth interviews with leaders of the Riksdag and survey data collected from Swedish MPs. First, we conducted 36 interviews between October and December 2020 with current leaders in the Riksdag, interviewing a total of 15 men and 21 women from all political parties (see Table A1 in the appendix).Footnote 2 The respondents included almost all the most prominent leaders in the Riksdag—all four Speakers (the Speaker and the three Deputy Speakers), seven of the eight party group leaders, seven of the eight deputy party group leaders, 15 of the 16 committee chairs, one deputy committee chair, and two former leaders. Many of the interviewees have served in a number of different leadership positions in the Riksdag, and several have a great degree of insight into the recruitment and nomination processes for the leadership positions in question. While these leaders vary in terms of gender and political party, they constitute a relatively homogeneous group in other respects, such as age and ethnic background. For instance, only a few of the leaders interviewed were younger than 40, and none had an immigrant background. The homogeneity of this group thus made it difficult to assess how other social identities may intersect with gender and influence conditions of leadership.

The parliamentary leaders generally showed a willingness to participate in the study, and almost all who received a request for an interview accepted.Footnote 3 The fact that the selection included almost all the top political leaders in the Riksdag in 2020 provided us with a good opportunity to obtain an accurate view of how leadership ideals are perceived and the implications of these perceptions.

We distributed a survey to all MPs during the second stage of the study in the spring of 2021, including the 36 interview respondents (all elected MPs), as a follow-up to the interview study. The primary purpose in this respect was to explore the MPs’ ideas concerning leadership ideals, including how they evaluated the exercise of leadership in the Riksdag. We also asked MPs about their present and past leadership experience to complement the interview study with a larger sample of past and present leaders (a total of 88 MPs indicated parliamentary leadership experience). In all, 76% of the MPs answered at least one survey item, and a total of 232 members of the Riksdag, or 66% of all MPs, answered the entire questionnaire. The survey respondents were, in general, representative of the members of the Riksdag (see Table A2).

One caveat regarding the material collected for this study is that although it is well suited for describing current leadership ideals and practices, it does not allow us to explore whether and how leadership ideals have changed over time, and if so, what accounts for such changes.

Analytical Approach

In accordance with the foregoing discussion, we argue that focusing only on leadership ideals is not sufficient for appraising the conditions of women’s political leadership. In addition to ideals, it is necessary to account for how women leaders are evaluated and treated in practice to reveal whether gender biases exist that lead to the unequal treatment of women leaders. Consequently, we focus on three issues in our analysis: (1) gendered leadership ideals, (2) evaluations of men and women leaders, and (3) the treatment of men and women leaders. This permits us to explore not only the gendered patterns in each of these dimensions, but also how these dimensions compare and relate to each other empirically. We view these dimensions as central components of the informal institutional context that shapes the conditions concerning women’s (and men’s) leadership. While leadership ideals reflect the norms of how a leader is expected to behave, evaluations and treatment of men and women leaders reveal the (gendered) practices surrounding leadership— most importantly, practices shaping how the MPs behave toward (men and women) leaders.

Role congruity theory explicitly focuses on the connections between ideals and evaluations. Role incongruity between leadership roles and female gender roles is expected to lead to prejudice, which, in turn, is expected to lead to less favorable evaluations of the leadership behavior of women leaders (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002, 576). While we maintain that is important to empirically study the relationship between ideals and evaluations, we add the treatment of leaders as third dimension. We argue that the ways in which leaders are treated by those they lead, the MPs, captures a broader range of practices—including MPs’ more subconscious ideas about gender and leadership—than what becomes evident from a survey question asking MPs to evaluate their leaders. Thus, adding treatment of leaders as a third dimension is in line with the broader range of gendered conditions emphasized by FI theory.

While we fully acknowledge that gender is not the only social identity of importance concerning the conditions of political leadership—gender interacts with a number of social identities, including age, sexuality, ability, nationality, and ethnicity (Mügge and Erzeel Reference Mügge and Erzeel2016)—the present study is limited to how gender shapes leadership conditions in the parliament.

Turning to the first step of our analysis—leadership ideals—we first identified a number of qualities, traits, and attributes associated with leadership and gender. It is important to note that gender should be viewed as a relational category that is changeable (Scott Reference Scott1986)—what is regarded as desirable or typical for women and men, including gendered leadership ideals, varies between contexts and over time. With this in mind, we took previous research as our starting point in categorizing “feminine” and “masculine” leadership qualities—qualities that have demonstrated “remarkable durability” across time and place (Burgess and Borgida Reference Burgess and Borgida1999, 670). While feminine attributes are typically described as “communal”—being socially responsible, nurturing, and oriented toward a collective good—masculine attributes have typically been viewed in “agentic” terms—assertive, controlling, and individualistic (Burgess and Borgida Reference Burgess and Borgida1999, 670).

Differences between men’s and women’s leadership have also been discussed in terms of “integrative” and “aggregative” leadership, with the former being more common among women and the latter more common among men (Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal1998). The integrative style focuses on resolving common problems, cooperation, and consensus, and involves a sensitivity to the context such that the qualities of listening and showing commitment to others are highlighted. In contrast, aggregative leadership focuses on managing conflicting interests and the leader uses his/her position to exercise power and resolve problems rather than seek common solutions. Here, politics is taken to be a power struggle. This categorization served as our analytical guideline (see Table 1).

Table 1. Masculine and feminine-coded traits

To assess contemporary leadership ideals in the Riksdag, we approached the leaders in an inductive manner. We asked them open-ended questions about what they consider desirable characteristics in a leader, whom they regarded as their ideal leader/role model for leadership, and how they would describe their own strengths and weaknesses as leaders. This combination of questions enabled us to triangulate respondents’ answers and pinpoint the qualities, traits, and attributes they regard as desirable in a political leader—that is, their leadership ideals. The analytical guideline for masculine and feminine traits (Table 1) was not presented to the MPs and did not serve as an interview guide. It is only used to analyze the responses of the leaders we interviewed.

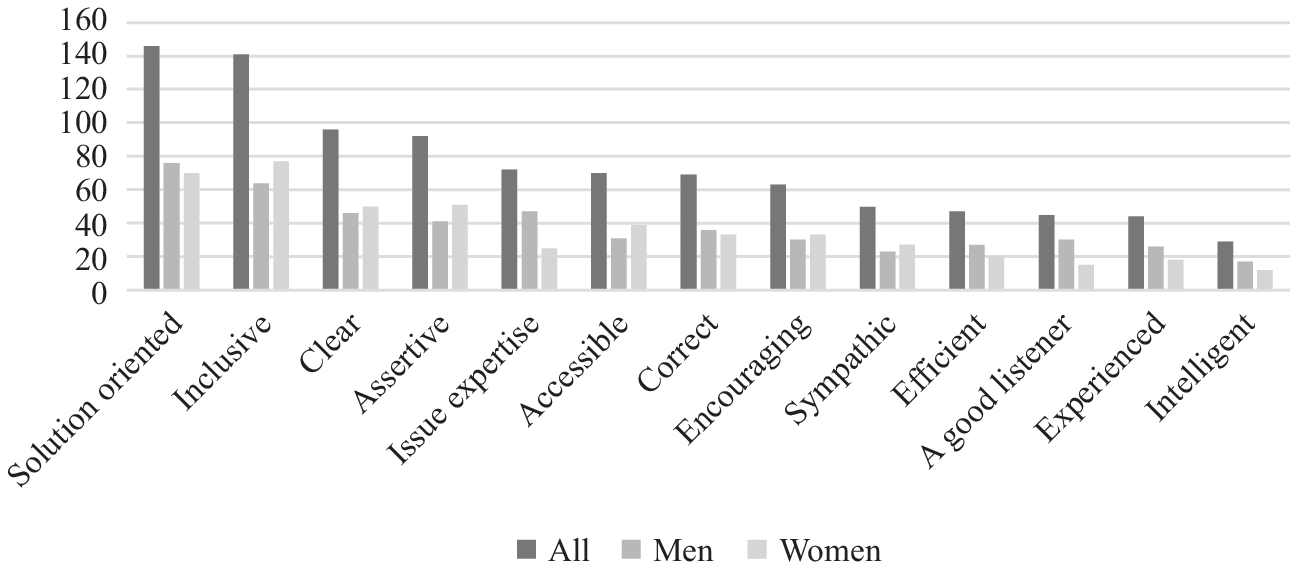

We further explore leadership ideals among all MPs by means of the survey. In the survey, we listed a number of potentially desirable leadership qualities (see Figure 2 below), drawing on both our analytical framework and our findings from the interviews, and asked respondents to evaluate how important they perceived them to be with respect to leadership in the Riksdag. In the survey, we did not indicate which of the listed qualities are commonly perceived to be masculine or feminine coded so as to not prompt the respondents with this information. We combine the interview and survey data sources to analyze whether leadership ideals are gendered in the sense that they emphasize masculine or feminine-coded qualities, and whether there are gender differences with respect to the leadership qualities that men and women MPs regard as desirable.

At the second stage of our analysis, we explore how Swedish MPs evaluate men and women Riksdag leaders. In particular, we analyze a set of a survey questions that asked MPs how satisfied they were with the leadership of (1) their committee chair, (2) their party group leader, and (3) their deputy party group leader. Finally, at the third stage of analysis, we explore gendered leadership practices in the Riksdag, investigating how men and women leaders are treated by the MPs they lead and whether they are favored or disfavored with respect to their leadership activities. In the interviews, we asked leaders whether they themselves had experienced negative treatment and how they perceived the treatment of men and women parliamentary leaders. In the survey, we asked all MPs with leadership experience in the Riksdag whether they had encountered negative treatment.

Analysis of Gendered Leadership Ideals, Evaluations, and Practices

Ideals: Are Leadership Ideals Gendered in the Riksdag?

First, we asked the leaders in the Riksdag to describe the leadership qualities that they regarded as ideal, which they themselves sought to acquire. Men and women leaders from both right-wing and left-wing political parties emphasized qualities that they—as well as previous research—identified as typically feminine coded, namely, being inclusive, being a good listener, being accessible, and having the ability to bring a group together:Footnote 4

I think [being a leader] is about seeing that there’s also a group, that there’s a need to create a group even if they consist of clearly individual characters. Not forgetting that, and not forgetting the role you have, that you may be the closest thing to a boss these people have. It’s about seeing people who aren’t doing well, who need support in order to be able to carry on with their tasks, and so on. I would say that’s a good … leader. (R29, woman)

… a person who is caring. Being able to meet members and believe it’s important to have direct contact. I think direct contact is important. I think it’s important for building relationships that you get to know people and have a dialogue with them. I think team building is important for all organizations, that you can build relationships with all individuals in order to create a group dynamic and be able to bridge differences that exist within a group, so that you have this private relationship building with each individual. (R30, man)

A smaller number of leaders mentioned more classically masculine attributes as desirable, including being assertive and formal. However, the vast majority emphasized that it is important to combine being inclusive and a good listener with the ability to put one’s foot down and be decisive when the situation calls for it:

To see other people, to listen and learn, I think that’s important. At the same time, you must not be afraid to make decisions. Sometimes there are conflicts, different opinions. If it’s my role to make a decision, it’s important to make it and stand for it so that there’s also clarity. (R4, man)

The more feminine-coded leadership ideal that leaders expressed is also reflected in their descriptions of their own leadership. The qualities that most leaders emphasized—both men and women—when asked to describe how they lead were inclusiveness and responsiveness. Many men, across party lines, described their own leadership in classically feminine terms such as taking the time to listen (R15, R16, R19, R23, R30, R4, R8), being accessible or present (R11, R19, R2, R3, R4, R8), and being inclusive (R12, R16, R2, R25, R3, R32, R33, R8):

In any case, that’s what people say, that I’m a good [leader]. I think I’m a good [leader] in the sense that I hear everyone, listen to everyone, and see everyone. (R16, man)

I believe a lot in a coaching type of leadership. Understanding and listening to the small steps that each MP can take to get more out of their work. … I try to be as present as possible…. My basic position is to listen, be rather nice, and socialize. (R3, man)

Many [MPs] who have had to work with me, when there were things that had to be sorted out, expressed afterwards that they’ve been happy with how I’ve listened and given consideration to what they’ve said and tried to find common ground. That I don’t order people around and push things through, and instead try to find other ways and listen. (R15, man)

These qualities are very different from those associated with typically masculine leadership. Although some men leaders admitted that decisions probably are made too quickly at times (R19, R2), other men remarked that the fact that they take the time to listen means that decision-making processes can take longer (R23, R8):

Yes. Sometimes they get a little impatient, they think that I let things take too long sometimes. I notice that. But it’s also my strategy that even if it’s a given how things will turn out, everyone must have their say. (R23, man)

Both men and women also emphasized that they prioritize getting the group they lead to function socially and that it is important for them to know how their group members are doing and what is happening in their private lives (men: R12, R19, R2, R25, R3; women: R28, R29, R18, R34, R6).

Although men and women described their own leadership in quite similar and primarily feminine terms, there were some gender differences. It is interesting to note that all the leaders who described themselves as tough, assertive, and even confrontational were women (R1, R5, R10, R36). As one woman put it,

I’m never unclear with what I think, I sound very decisive. […] You could probably say that I have a masculine way of working because I’m very direct and frank. (R1, woman)

These women, who come from both left-wing and right-wing political parties, emphasized that they have more feminine qualities, such as being inclusive, accessible, kind, and responsive. It is noteworthy that none of the men respondents described their leadership in such terms as being tough or assertive.

Another gender difference that emerged in the respondents’ descriptions of themselves as leaders is that more men than women spoke of themselves as formal, stating that they placed a high priority on sticking to the formal rules and structures (R12, R30, R32, R33, R4, R31). This is a trait that many respondents regarded as more common among men leaders. Nonetheless, only a small number of respondents highlighted being formal when speaking about how they viewed ideal leadership. The only exception was a man who described himself as formal, remarking that “the social is important, even if being formal, sticking to the structures and the rules, and being decisive is often more important” (R32).

It is important to keep in mind, however, that gender differences with respect to how men and women describe their own leadership do not necessarily mean that there are actual differences in how they lead in the Riksdag, as such descriptions may be colored by gendered expectations and interviewer effects. For example, even though men might be assertive in certain situations, they may not wish to express this in an interview. In contrast, women who go against gendered expectations by being tough may have a clearer need to emphasize such qualities in an interview of this type. Nevertheless, although we recognize that it is important to take such potential interviewer effects into consideration, we do not believe that they explain why we found a predominantly feminine leadership ideal in the Riksdag. By asking respondents a set of different questions surrounding leadership ideals, including how they perceive their own leadership and the leadership of their colleagues, we were able to cross-check and triangulate the responses.Footnote 5

On the basis of leaders’ views of themselves, we conclude that the ideal leadership qualities more closely resemble qualities that are often regarded as typically feminine, such as sensitivity, accessibility, and inclusivity. These results stand in contrast with previous research that has emphasized how leadership ideals are often more closely associated with qualities perceived as typically masculine, such as individualism and decisiveness. Respondents with long experience in the Riksdag did perceive that leadership ideals had changed over time in a feminine direction, and they connected this to the growing proportion of women in leading positions (R27, R22). While this is noteworthy and suggests a connection between women’s descriptive representation and leadership ideals, the design of this study unfortunately does not allow us to establish whether such ideals have changed over time.

In the survey, we asked all MPs about the qualities they viewed as most important for Riksdag leaders. We provided them with a list of potentially desirable leadership qualities (drawn up based on traits mentioned in the interviews and previous research) and asked them to mark a maximum of four qualities that they regarded as most important in this regard. The list did not include information about whether the qualities are commonly characterized as masculine or feminine coded. The MPs’ responses confirmed to a degree our findings from the interviews with leaders, insofar as MPs apparently do not prefer leaders with markedly masculine skills and traits. The four qualities that the MPs most preferred were solution oriented, inclusive, clear, and assertive, with solution oriented and inclusive being the most popular. The last two may be characterized as typically feminine qualities, while clarity and assertiveness are more often associated with masculine traits. The ideal that emerge from the survey responses thus combines both feminine and masculine-coded attributes, although more emphasis is placed on feminine-coded traits. It is notable that men MPs prioritized issue expertise to a greater degree than women MPs, while women MPs placed a greater value on inclusivity (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Ideal leadership qualities: Views of men and women MPs. Survey question: “What qualities do you consider to be most important for a leader in the Riksdag?” (select a maximum of four options).

In summary, the views of both Riksdag leaders and MPs regarding ideal leadership qualities indicate that they do not prioritize a masculine-coded leadership ideal over a feminine-coded ideal. They instead appear to prefer a mix of feminine and masculine traits and skills in their leaders, with the emphasis clearly being placed upon such feminine qualities as prioritizing the group and being solution oriented and inclusive. Therefore, current leadership ideals in the Riksdag suggest that the context is of great importance for how leadership ideals are shaped and gendered.

Evaluations: How Satisfied Are MPs with Men’s and Women’s Parliamentary Leadership?

Second, we explore how MPs evaluate men and women leaders in the Riksdag. On the basis of role congruity theory, we would expect that the emphasis on feminine-coded leadership ideals found in the first part of the analysis would lead to higher evaluations of women leaders.

In the survey, we asked MPs three different but similarly phrased questions about how satisfied they were with the leadership of (1) their committee chair, (2) their party group leader, and (3) their deputy party group leader.Footnote 6 MPs evaluated a total of 32 individual leaders, including 16 committee chairs, 8 party group leaders, and 8 deputy party group leaders.Footnote 7 Overall, we find that MPs are very satisfied with the leadership of their Riksdag leaders.

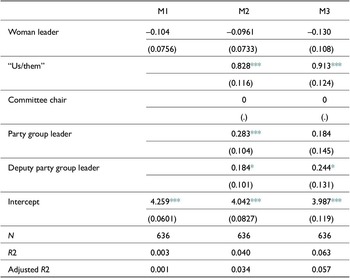

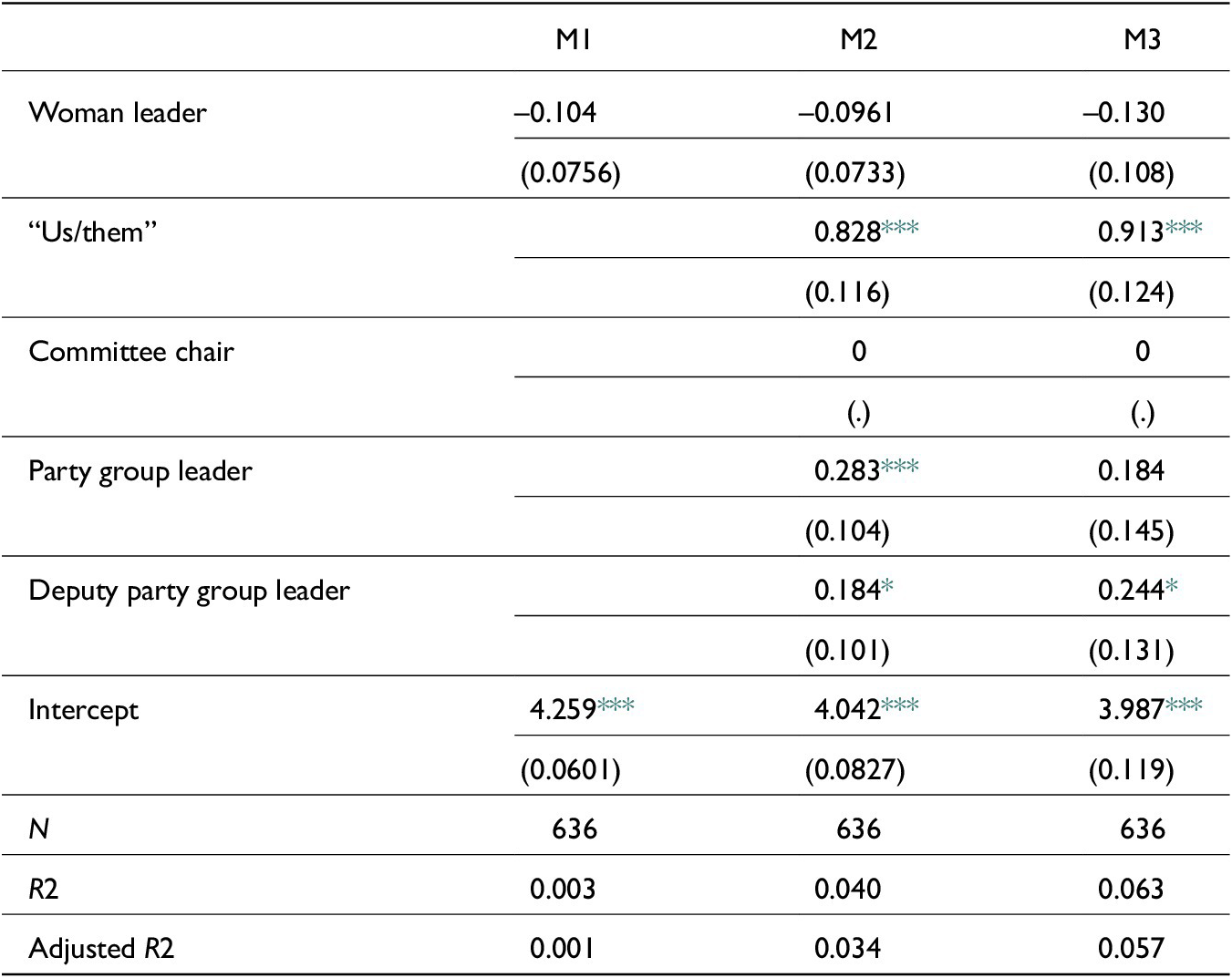

The first analysis (M1) in Table 2 indicates that the differences in satisfaction scores between men and women leaders are very small and not statistically significant—men and women leaders received average scores of 4.26 and 4.16, respectively, on a 5-point scale from not at all satisfied (1) to very satisfied (5). This nonsignificant gender difference is robust to adding controls for leader type (committee chair, party group leader, and vice party group leader) and an “us-them effect” (see M2 and M3 in Table 2). The latter captures the effect of belonging to the same political party as the leader in a multiparty setting—a parliamentary committee.Footnote 8 Not surprisingly, men and women MPs belonging to the same political party as their committee chair tend to be more satisfied with their leader. In Model 3 (M3 in Table 2), leaders’ scores are weighted and control for the fact that different leaders received different numbers of evaluations.Footnote 9 In all three models, the standard errors are clustered on individual respondents (recall that each respondent answered three survey questions about three different political leaders).

Table 2. Difference in satisfaction scores for men and women leaders, OLS regression

Notes: Survey question (dependent variable): “Overall, how satisfied are you with the leadership of your [1. party group leader, 2. deputy party group leader, 3. committee chair]?” Responses were recorded on a 5-point scale, where 1 = not at all satisfied, 2 = rather dissatisfied, 3 = neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 4 = rather satisfied, and 5 = very satisfied. One observation corresponds to one MPs’ evaluation of one leader (committee chair, party group leader, and deputy party group leader). Woman leader reports the differences in satisfaction with women and men leaders. M2 and M3 include controls for leader type (committee chair is the reference category) and an “us/them” effect. Leaders’ satisfaction scores are weighted in M3, controlling for the number of evaluations each leader has received. Respondent clustered standard errors in parentheses.

***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1.

When we examine the support for different types of leaders separately (see Table A3), slight differences emerge regarding support for men and women leaders. Notably, MPs who have women committee leaders are slightly less satisfied with their leaders than MPs with men committee chairs. On the other hand, MPs with women group leaders are slightly more satisfied with their leaders than MPs who have men group leaders, although the difference is not statistically significant. In addition, we also run separate models for men and women respondents (see Table A4). In line with recent research concerning leadership evaluations (Funk, Jensen, Molina et al. Reference Funk, Jensen, Molina and Stritch2021), we find that both men and women MPs are equally satisfied with men and women leaders.

In summary, our results indicate that women are not evaluated in less favorable terms than men. In fact, Swedish MPs appear to be equally satisfied with the leadership of both men and women in the Riksdag. This is noteworthy insofar as previous research found that women leaders in general tend to be evaluated more negatively than men in politics (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2014) and in other contexts (Salin Reference Salin2020), and the present results should be interpreted with this in mind. Although women are not favored over men in the Riksdag, they do fair rather well.

Practices: Are Men and Women Leaders Favored or Disfavored in Practice?

Third, we explore the connection between leadership ideals and how men and women leaders experience being leaders in the Riksdag, including how they are treated by their colleagues. Role congruity theory maintains that a more feminine-coded leadership ideal should suit women better and weaken prejudice against women holding leading positions. It is even possible that women leaders are favored over men by such feminine-coded ideals. While the results of our evaluations indicate a positive trend, with women leaders being evaluated on equal terms as men, FI reminds us that leadership is embedded in a broader institutional—and gendered—context. In this respect, previous research has indicated that gender inequalities may persist even though Swedish politics as such has progressed and become less masculine.

Our interviews with parliamentary leaders indicate that most are very happy with their general working conditions. In addition, there appears to be broad support among the leaders for a gender-equal leadership, including equal working conditions and even distribution of leadership positions between men and women. Respondents with experience of nomination procedures attest that great consideration is given to gender balance when appointing leaders to various positions and that there is consensus in this respect across party lines (R22). Although there are no formal rules in the Riksdag, such as gender quotas, for determining the gender distribution in leading positions, several respondents stated that a practice of gender balance has emerged across party lines (R7, R22).

Nevertheless, an analysis of the interviews and survey responses indicates that gender inequalities and related problems continue to exist in practice, and at least some women leaders face greater obstacles in their work. One problem brought up by several leaders in the interviews is that there are differing requirements and expectations for men and women who hold leadership positions, and this creates obstacles for women. A number of respondents believed that more is required of women leaders—they are expected to be very well prepared and competent.

If you look at the whole organization, you can clearly see that more is still required from us women in a way. We don’t get away as easily with being a little careless…. You have to be flawless in some way. Otherwise, you will be easily criticized. (R27, woman)

I don’t know what to say. I still think it’s evident that men are perceived as competent “per se,” while we women need to show that we’re competent in other ways. (R36, woman)

A related issue brought up by a number of respondents, most of them women, is that women leaders are examined, questioned, and criticized to a greater degree than men (R27, R17, R19, R22, R24, R31, R5, R7). Such criticism, which may come from both women and men, refers to their competence, behavior, and appearance.

I think men get away with things more easily than women. I think women are more scrutinized. Above all, I think women talk more about women managers or leaders. I don’t know why, but that’s how I experience it. A woman… from how she dresses to how she behaves, which one might not have commented on if it had been a man. Preferably something a little more negative. If you’re too good-looking or ugly. Whatever it is. There’s much more commentary about women. If she’s not clear enough, that’s not good. If she’s too clear, that’s not good either. (R22, woman)

The picture is very clear. Views on what women say, how women dress, hair. It can happen to men, too, yes.… But not very much. (R24, woman)

When taking into consideration what leaders stated about how they had been treated on the personal level in their leadership roles, we find further indications that gender problems continue to exist in practice. While a majority of the leaders feel that they in general are treated in a good and respectful manner (24 of 35), there are also indications of negative treatment of women leaders. To varying degrees, a group of women from both right-wing and left-wing political parties have been treated inappropriately and/or feel that they have been questioned in their role as leaders. Almost half the women leaders interviewed for this study (9 of 21) reported such experiences. They have all experienced their leadership being questioned in various ways, all of which may be regarded as illegitimate or inappropriate. This is not simply a matter of disagreement or criticism, but rather a matter of these women’s competence and suitability as leaders being called into question.

One woman from this group described a situation when she took office in the following terms:

At first, I felt like I was a substitute teacher in high school because there were so many older men who thought it was strange that I, a young woman, had been given this fine position. [They] tried all the domination techniques, all the tricks, everything, and it went on for about six months. Then they got tired of trying to put me in my place. (RNN)Footnote 10

She added that her authority as a leader was questioned before the group as a whole, and she was accused of not knowing the regulations, even though it was obvious to the majority of the group that this was not the case. She also recounted how she was repeatedly criticized for how she handled formalities, a critique that appeared to be aimed at disturbing order. Another woman with similar experiences of being called into question related how a group of men repeatedly attempted at the beginning of her leadership term to influence her decisions in an inappropriate way. This became particularly obvious with respect to issues that are normally decided by the leader herself, when several men who held opposing views criticized her decisions (RNN). Her experiences were confirmed by two other respondents who witnessed how this woman was questioned in a way that her men predecessors in the position had not been (RNN, RNN). One respondent described the situation as follows:

There [is] more questioning, now, when it’s a woman leader…. When it’s a woman, then there’s more questioning about her, like, “Wow, should she have an opinion on that?” And that criticism is also expressed to her. That is not something that would have happened to our former [men leaders], that I can say for sure…. Somehow it’s, like, people view men leaders as having a higher status, so you don’t say anything or question them. One can surely talk about them, but not to them, and you don’t question their leadership. But obviously, a number of people feel that it’s legitimate to do so when it’s a woman who’s the leader. (RNN)

Further examples of treatment considered to be inappropriate are clerks questioning the decisions of women leaders, even though that is outside their mandate (RNN, RNN), collective questioning and criticism of decisions in front of the entire group (RNN), and people without leadership positions or special competencies assuming the right to openly review the leadership and express their views on how it is conducted (RNN).

Only a small number of men leaders we interviewed for this study reported similar experiences of feeling that their leadership had been questioned. Two other men who reported having been treated inappropriately endured criticism because they had become involved in a conflict between political parties, but they described it as not being directed toward them personally (RNN, RNN). In sum, our analysis of the interviews with Riksdag leaders reveals that there are gender differences in terms of treatment. In spite of the existence and acceptance of feminine-coded leadership ideals and positive evaluations, we find that women leaders, to a greater extent than men, report that they are treated in a way that undermine them as leaders.

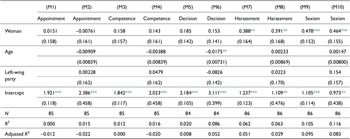

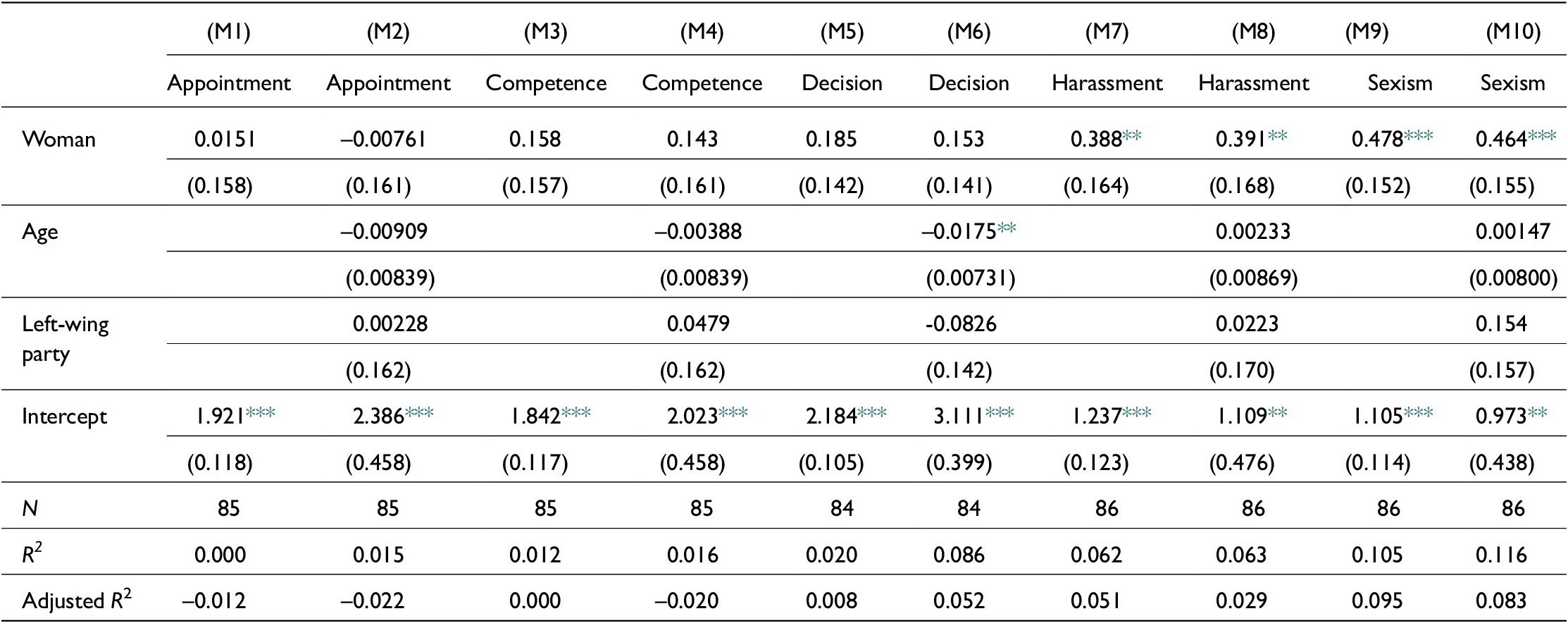

In addition to interviewing current parliamentary leaders, we posed questions in the survey to all MPs who stated that they had held leadership positions in the Riksdag, inquiring about how they felt they had been treated in their leadership roles.Footnote 11 In accord with the interview results, it appears that the great majority of the parliamentary leaders have been treated well, although certain gendered problems appear to remain. Table 3 presents the differences between men’s and women’s responses to five different survey items related to treatment. First, there were no statistically significant differences between the responses of men and women leaders with respect to whether others had questioned their (1) appointment to a leadership position, (2) competence as a leader, or (3) decisions as a leader. This applies both to the bivariate models (M1, M3, and M5 in Table 3) and to the models in which we include controls for the leaders’ age and whether they belonged to a left-wing party, namely, the Social Democrats, the Left Party, or the Green Party (M2, M4, and M6 in Table 3). For these three survey items—appointment, competence, and decisions—men and women on average reported that they had seldom experienced being questioned.Footnote 12

Table 3. Treatment of parliamentary leaders, OLS regression

Notes: Survey question: “How often in your role as leader of the Riksdag have you been exposed to the following?” Responses were recorded on a 5-point scale where 1 = never, 2 = seldom, 3 = sometimes, 4 = regularly, and 5 = very often. Specific items were Appointment: “Your appointment to a leadership position has been questioned. Competence: Your competence has been questioned. Decisions: Your decisions have been questioned.” Harassment: “You have been exposed to harassment. Sexism: You have been exposed to sexist comments.” Woman reports the difference between women’s and men’s responses. M2, M4, M6, M8, and M10 include controls for the leader’s age and party family (Social Democrats, Left Party, and Green Party coded as left-wing = 1; Moderates, Liberals, Centre Party, Christian Democrats, and Sweden Democrats coded as right-wing = 0). Standard errors in parentheses.

***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1.

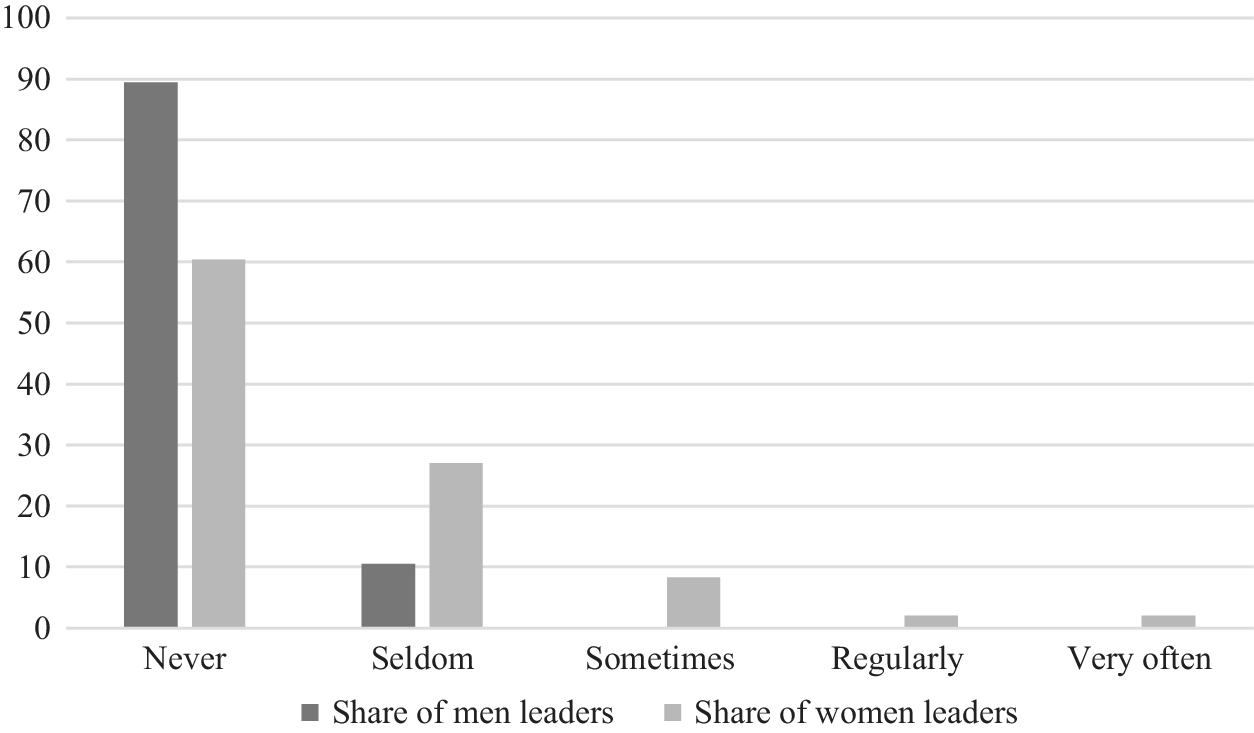

However, women experience more harassment and sexist comments in their role as parliamentary leaders. The differences between the responses of men and women leaders are statistically significant in this respect, both in the bivariate models (M7 and M9 in Table 3) and when we include controls for leaders’ age and whether they belong to a left-wing party (M8 and M10 in Table 3).Footnote 13 Among former and current parliamentary leaders, 21% of the men and 44% of the women reported that they had been subjected to harassment in their role as leaders in the Riksdag, although this had occurred only “seldom” for many leaders. However, a small number of women reported that they had been subjected to harassment more regularly, or even very often, in their role as leaders in the Riksdag (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Proportions of men and women leaders exposed to harassment. Survey question: “In your role as a leader in the Riksdag, how often have you been exposed to harassment?” Responses were recorded on a 5-point scale from 1 = never to 5 = very often. N = 88 (38 men, 50 women).

In addition, 11% of men leaders and 40% of women leaders stated that they had been exposed to sexist comments in their role as leaders. A small number of women leaders stated that they had received sexist comments regularly or very often (see Figure 4). From a broader perspective, this should be regarded as a relatively large group of leaders being exposed to sexist treatment. For instance, Folke et al. (Reference Folke, Rickne, Tanaka and Tateishi2020), using a more inclusive measure of self- reported sexual harassment, found that 20% of Swedish women managers, 30% of American women managers, and 25% of Japanese women managers had been exposed to sexism in the previous 12 months.Footnote 14

Figure 4. Proportions of men and women leaders exposed to sexist comments. Survey question: “In your role as leader in the Riksdag, how often have you been exposed to sexist comments?” Responses were recorded on a 5-point scale from 1 = never to 5 = very often. N = 88 (38 men, 50 women).

In short, in spite of a more feminine-coded leadership ideal and the fact that men and women MPs appear to be equally satisfied with men and women leaders, leadership practices in the Riksdag are still gendered in a way that disadvantages women leaders. Women leaders are questioned, criticized, and harassed to a higher extent than men, which could undermine their leadership competence and legitimacy. Several of the women we interviewed testified that they had experienced such negative implications.

Concluding Discussion

When and why do women face inequalities related to their gender in political leadership? It is widely known that women political leaders are disadvantaged in male-dominated contexts. This fact is often attributed to role incongruity, whereby masculine-coded leadership ideals clash with behavior deemed appropriate for women. However, in spite of the rapid increase in the numbers of women in political leadership positions across the globe, we know much less about the conditions for women’s leadership in more gender-balanced contexts. In this article, we address this gap through a study of leadership ideals, evaluations, and treatment in one of the world’s most gender-equal political contexts—Sweden, and more specifically, the Swedish parliament or Riksdag.

In contrast with expectations derived from classical role congruity theory, we find that a predominantly feminine leadership ideal coexists with masculine leadership practices. While both men and women across the left-right political spectrum emphasize qualities associated with femininity as desirable for a leader—such as inclusion and the importance of listening and finding broad solutions—and MPs evaluate men and women leaders in equally positive terms, women leaders still appear to be systematically disadvantaged in practice. In comparison with men, women leaders across party lines more often experience being scrutinized, criticized, and held to higher standards, and they are more exposed to harassment and sexist comments. The findings are in line with previous research on the Swedish parliament: while the Riksdag displays a high level of gender sensitivity (Erikson and Freidenvall Reference Erikson and Freidenvall2020; Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2015), there are signs of remaining informal masculine norms and practices (Erikson and Josefsson Reference Erikson and Josefsson2019).

Our findings have both theoretical and empirical implications for the study of gender and political leadership. First, they indicate the importance of studying leadership ideals empirically and being open to the fact that the construction of leadership roles varies across contexts. In a world where women now hold more political leadership positions than ever before, we cannot simply continue to assume that leadership ideals will always remain masculine coded. Second, our finding that women remain disadvantaged in practice, in spite of a feminine leadership ideal and positive evaluations, highlights the limitations of the widely employed classical role congruity theory for explaining when and why women are disadvantaged in political leadership. Stated otherwise, the present study reveals that the link between leadership ideals and practices is more complex than has previously been suggested.

On a theoretical level, we argue a that more comprehensive understanding of the embeddedness of leadership ideals and leadership practices in the broader gendered institutional context is necessary for the theorization of gender and political leadership. FI provides a useful point of departure in this endeavor. Politics is a context in which gender is both constructed and constitutive in various interlinked processes at the organizational, normative, symbolic, and individual levels (Acker Reference Acker1992; Lowndes Reference Lowndes2020; Scott Reference Scott1986). FI scholars have highlighted this interaction between different institutions—as well as the fact that their various functions are both restrictive and conducive to gender equitable changes (see, e.g., Waylen Reference Waylen2014, Reference Waylen and Waylen2017).

With respect to leadership more specifically, our findings suggest that the propensity for change may differ between leadership norms and practices. Insofar as the leadership ideals we have assessed are conscious in character, these likely reflect institutionalized gender-equality norms in the Riksdag. Our careful and triangulated analysis in fact indicates genuine support for a feminine leadership ideal across the left-right spectrum of political parties. Even if a desirability bias may have influenced our results, such a bias would in itself be a manifestation of a strong norm present in this regard. In contrast, practices and routinized behavior, which appear to remain gendered in ways that disfavor women, comprise a type of institutional feature that rather resembles habitus (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu, Rooksby and Hillier2017), which is more informed by tradition, less conscious, and thus more likely resistant to change. Changed norms might nonetheless be a first step toward changing practices, which could be reflected in the overall positive evaluations of women leaders that we have identified.

To gain a better understanding of when and why women face gendered obstacles in political leadership, future studies should elaborate on how different informal institutions relate to each other, interact, and create different outcomes with respect to gendered leadership ideals and practices. While this study has described different aspects of gendered leadership conditions in one of the world’s most gender-equal political contexts, our research design does not permit us to explain whether a more feminine leadership ideal has emerged as an effect of the increased numbers of women MPs, or whether Swedish egalitarian culture explains both the numerical gender balance and the comparatively favorable conditions for women political leaders. In this respect, studies that compare leadership ideals and practices over time in one context or across different contexts could provide valuable insights into the importance of differently gender-balanced contexts and how ideals and practices are related both to the given context and to each other.

Another limitation concerning the present study is that it is focused on parliamentary leadership, including such roles as committee chairs and party bench leaders, which has received less research interest than other forms of political leadership. In contrast with the roles of party leader or cabinet minister, parliamentary leadership roles involve a great deal of socially complex activities, and we might expect that the ideals associated with these roles could be more inclined to changes that favor women (see, e.g., Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). Likewise, the Swedish consensual parliamentary model might also have a similar impact in that it might be more favorable to women. The extent to which our findings are applicable to other types of political leadership and parliamentary models, including more confrontational Westminster culture as the Westminster model, thus warrants further investigation.

Further work is also needed regarding how the intersection between different social identities shapes the “experiences of discrimination and marginalization as well as those of power and privilege” (Mügge and Erzeel Reference Mügge and Erzeel2016, 500) with respect to political leadership. Although the present study is limited to gender, we acknowledge that intersections between gender, class, age, and ethnicity most likely influence conditions for leadership in significant ways.

In conclusion, insofar as the presence of women at the very top of the political ladder continues to grow, research must update and revise existing theories and empirical knowledge that seek to explain gender (in)equality in political leadership to keep up with the changes now taking place in society. Even if the Riksdag has not managed to fully abolish gender inequalities in regard to leadership, conscious gender-equality work is important. In particular, the informal rule of gender-balanced appointments to leading positions deserves to be mentioned as a decisive change—it appears to be widely supported among MPs and it has been successful in getting women into leading positions in the Riksdag.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X23000090.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE), grant number: 2018-01027, and the Swedish Research Council (VR), grant number: 2022-02231.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.