With the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision on June 24, 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade (1973), reversing longstanding constitutional protections for women’s abortion rights and resources. Later that year, on November 8, 2022, the midterm elections saw a record number of voters that exceeded nearly all turnout rates in midterms since 1970, only slightly surpassed by the one in 2018 (Murphy Reference Murphy2023; Hartig et al. Reference Hartig, Daniller, Keeter and Van Green2023). To the surprise of many pundits, the prediction that a “Red Wave” vote would allow Republicans to take over the Senate and win the House of Representatives by large margins turned out to be wrong. Instead, Republicans gained only 9 seats to narrowly capture the House while Democrats maintained control of the Senate through key battleground victories across the nation, even picking up a Senate seat in Pennsylvania (Sprunt Reference Sprunt2022; Balz Reference Balz2023). Since then, there has been wide speculation that the overturning of Roe v. Wade helped motivate and drive voter turnout, especially among pro-choice women and the youth.

Our main research question in this study is that if one assumes the overturning of Roe v. Wade influenced voter mobilization in the 2022 midterms, what was the key mechanism through which this effect occurred? In other words, what made those opposed to the Dobbs ruling more politically active in the 2022 midterm elections? We propose that group empathy (especially for groups in distress) was the primary motivational mechanism driving the relationship between opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade and voter mobilization, even more so than self-interest or identity.

Although the argument that opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade singlehandedly drove a powerful “Blue Tsunami” or “Roevember” turnout seems intuitive and straightforward at first glance, it may have been too hasty a presumption in hindsight. The election statistics on voter turnout by gender, age, and partisanship suggest that opposition to the Dobbs ruling out of self-interest or identity was not enough of a catalyst for mobilization and that something else was at play. With only a few months between the SCOTUS ruling and the midterm elections, many Americans had just begun contemplating the significance of the ruling. Yet it would take some time before its full implications and socioeconomic impact on women could be felt widely as major policy changes started being implemented and reported on across the country. We think it is more plausible that voters who possess a stronger predisposition to empathize with the struggles of marginalized groups would internalize more quickly and intensely the far-reaching implications of the Dobbs decision above and beyond self-interest or identity-based considerations. Equipped with empathic concern and perspective taking skills, such voters would be much more cognizant and motivated to care about others who would be most adversely affected by the Dobbs ruling moving forward.

Our analyses of an original nationally representative survey conducted by YouGov in March 2023 corroborate these expectations. We find that opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade—though a highly salient issue on many voters’ minds—did not significantly affect one’s likelihood to vote unless one is empathic toward groups in distress. Through interactive statistical models, we show that such opposition was actually demobilizing for those who scored low in group empathy and thus lacked the motivation to care. Our findings indicate that group empathy serves as a catalyst that prompts people to act on their opposition to key policies and political decisions that stigmatize and harm disadvantaged groups in society, in this case women as a marginalized political minority losing their constitutional right to bodily autonomy and access to reproductive care.

The Overturning of Roe v. Wade and the 2022 Midterms

In late September 2022, filmmaker Michael Moore appeared on Real Time with Bill Maher to make one of his bold predictions. He prophesied that, contrary to expectations set by many news outlets about the impending midterms, a highly anticipated “Red Wave” vote would fail to materialize and that, instead, “a massive turnout of women” and others from the left would help Democrats keep control of Congress (Folmar Reference Folmar2022; Tinico Reference Tinico2022). Such an occurrence would be fueled by voters dismayed by the overturning of Roe v. Wade at the hands of the conservative Supreme Court Justices, including Donald Trump’s three appointees—Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett—who ultimately tipped the scales to revoke women’s abortion rights. As evidence to back his expectations, Moore pointed to the way voters in Kansas had just defeated a ballot measure that would have allowed a statewide ban on abortion, and how 70% of newly registered voters in that state were women fighting to regain and retain their rights (see Paris and Cohn Reference Paris and Cohn2022).

Despite the common occurrence that presidents tend to lose congressional seats in the first midterm elections after assuming office, Moore was not deterred—nor was he alone—in counter-predicting a “Blue Tsunami” of voters that would offset the projected “Red Wave.” In fact, the catchphrase “Roevember” became not only a trending riff on November’s midterm elections, but the symbol of a forecast by a number of political figures, analysts, and civil rights groups that the overturning of Roe v. Wade would drive voters to the polls for political payback (Ruiz Reference Ruiz2022). Because the Supreme Court decision went so strikingly against public opinion trends demonstrating strong majority support for abortion rights in recent years (see Pew Research Center 2024), some expected the controversial ruling could also stir a notable backlash among independent voters and perhaps even some Republicans.Footnote 1

In the immediate aftermath of the 2022 midterms, Michael Moore took to social media in victorious fashion to celebrate the election results:

There was so much heartening news coming out of last night. Abortion rights measures passing in Vermont, California, Michigan, and Kentucky—with Montana poised to follow suit…We were lied to for months by the pundits and pollsters and the media. Voters had not ‘moved on’ from the Supreme Court’s decision to debase and humiliate women by taking federal control over their reproductive organs. Crime was not at the forefront of the voters’ ‘simple’ minds. Neither was the price of milk. It was their Democracy that they came to fight for yesterday. Footnote 2

Likewise, President Joe Biden celebrated a “good day for democracy,” congratulating members of his Democratic Party on a best-in-decades outcome that defied the typical results for a president’s first midterms (Cadelago and Ward Reference Cadelago and Ward2022). Were these election results largely attributable to voters—particularly women and other women’s rights activists—outraged by the overturning of a half-century’s worth of women’s abortion rights just months prior to the election? While many pundits and politicians bandwagoned on the idea that “Roevember” became a reality and played a pivotal role in driving the historic results, there needs to be more systematic, empirical investigation into the underlying motivational factors that led people to turn out and vote the way they did in contrast to the typical midterm elections of the past.

Midterm Results at a Glance

It is useful to zoom out to see whether public attitudes about abortion rights could potentially drive voter mobilization in the aftermath of the Dobbs ruling. Looking at baseline abortion attitudes among Americans over the past several decades, there has been a highly consistent majority of public support for abortion (see Figure 1; Pew Research Center 2024). In recent years, public opinion trends show particularly strong support for abortion rising from 57% in 2016 up to 62% by mid-2022 among those agreeing abortion should be “legal in all or most cases” while opposition to abortion during that same period fluctuated between 36–40% among those saying abortion should be “illegal in all or most cases.”Footnote 3 Subsequently, a large 57% majority of Americans disapproved of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs ruling that revoked constitutional protections for women’s abortion rights (Pew Research Center 2022). Such polling data lends credence to the notion that voters opposed to the overturning of Roe v. Wade might have been motivated to turnout in high numbers and thus counteract what might have otherwise led to a “Red Wave” vote.

Figure 1. Views on abortion, 1995-2024.

Note. Data points indicate percentage of U.S. adults who say abortion should be legal versus illegal in all/most cases. Data since 2019 is from Pew Research Center’s online American Trends Panel; prior data is from telephone surveys. Data for 1995-2005 is from ABC News/Washington Post polls; data for 2006 is from an AP-Ipsos poll.

Source: Pew Research Center.

According to exit polls and election-day/postelection surveys, abortion had ranked as the second or third most important issue for voter decision behind “inflation and the economy” and “protecting democracy” (see Jacobson Reference Jacobson2023, Reference Jacobson8–Reference Jacobson10).Footnote 4 In addition, survey data collected the week prior to the day of the elections reported that 57% of Democrats felt the overturning of Roe v. Wade would have a “major impact” on their decision to vote compared to only 22% of Republicans.Footnote 5 In the same survey, 47% of pro-choice voters said the Dobbs ruling would significantly affect their decision to vote compared to merely 22% of pro-life voters. On the heels of the midterms, these numbers suggested that voter turnout among Democrats and pro-choice advocates could potentially be higher and more impactful than in previous elections. But did these attitudinal trends translate into actual voting behavior at the 2022 midterms?

A closer look into turnout rates for the 2022 midterms reveals somewhat of a different story than the “Roevember” and “Blue Tsunami” presuppositions. It is true that the 2022 midterm voter turnout rates (52.2%) were very close to the record-high rates observed for the 2018 midterm elections (53.4%). The registration rates were also the highest for a midterm election in more than two decades (69.1%) and indeed 2.2 percentage points higher than those in 2018 (U.S. Census Bureau 2023). Yet surprisingly, according to U.S. Census Bureau data from the Current Population Survey, “the groups with the highest Democratic voting margins—in particular, young people, Black Americans, women, and White female college graduates—did not show greater turnout increases than other groups, and often displayed lower turnout rates than in the 2018 midterms” (Frey Reference Frey2023).

An inspection of gender voting patterns does not align well with the “Roevember” and “Blue Tsunami” arguments either. According to a 2023 Pew Research Center report, “the gender gap in 2022 vote preferences was roughly similar to the gaps in 2020 and 2018. And even as men continued to be more likely than women to favor GOP candidates, Republicans improved their performance among both groups compared with 2018” (Hartig et al. Reference Hartig, Daniller, Keeter and Van Green2023, Reference Hartig, Daniller, Keeter and Van Green19). While only 40% of women voters cast ballots for GOP candidates in 2018, the Republican Party gained support from a higher share of women in 2022 with 48% of females voting Republican.

These summary statistics, of course, are not sufficient to draw any concrete conclusions about the impact the overruling of Roe v. Wade might have had on voter mobilization. In fact, one should exercise caution in comparing turnout rates—especially partisan turnout—between the 2018 and 2022 midterms. The former took place during the highly controversial Trump presidency that mobilized Democrats in record numbers while the latter happened with Democrat President Biden beset by high inflation and disaffected partisans.Footnote 6 Some may even argue that the conditions of the 2022 midterms were actually more similar to the 2014 midterms during President Barack Obama’s second term, which resulted in Republicans taking the Senate and securing the largest House majority since 1928. That election cycle saw a historically low turnout, especially among the key Democratic voting blocks that had helped re-elect President Obama in 2012 (see Blake Reference Blake2014; Judis Reference Judis2014). Yet, while the 2014 turnout rate was the lowest observed since World War II, voter turnout in the 2022 midterms was the second highest (after 2018) in more than five decades.

With these considerations in mind, the key question then is: what was the motivational mechanism that kept disaffected voters who opposed the 2022 Dobbs ruling from staying home that year and thus counteracting a return to a more typical midterm pattern that might have otherwise produced a “Red Wave”? We suspect mere opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade might not have had a straightforward path in shaping voting behavior in the 2022 midterm elections. We argue instead that empathy for marginalized groups likely played a crucial, moderating role in linking such opposition to voter mobilization, and perhaps even more so than self-interest or identity. We posit those who possess high empathy for groups in distress were the ones most motivated to participate and vote in the 2022 midterms in reaction to the reversal of Roe v. Wade. We put forth our theory and expectations in the next section.

Theory and Hypotheses

We employ Group Empathy Theory to derive our hypotheses on the links between group empathy, attitudes toward the overturning of Roe v. Wade, and voting behavior in the 2022 midterm elections. Group Empathy Theory, developed by Sirin, Valentino, and Villalobos (Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2016a, Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2016b, Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2017, Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2021), posits that one’s general predisposition to empathize with groups in distress shapes one’s political attitudes and behavior, including by boosting support for the rights of such groups and increasing opposition to policies that harm them. The motivational role of group empathy on policy views and political action is powerful enough to withstand or even surpass the effects of perceived threats, competition, partisanship, ideology, and other influential belief systems such as authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, racial resentment, and ethnocentrism. The theory has been tested systematically in cross-national contexts, various policy areas, and across different administrative periods through multiple nationally representative experimental and survey studies, demonstrating strong explanatory power and generalizability.

The initial focus of Group Empathy Theory was to examine the role of empathy among racial/ethnic groups in shaping policy preferences and political behavior concerning race/ethnicity-related issues such as immigration and national security (see Sirin et al. Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2016a, Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2016b, Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2017). In this study, we test this theory in the context of another group-related policy issue—abortion rights—for which the focal group in distress is gender-based. Research has shown that group-level empathy as a trait is applied not only to racial/ethnic groups, but also more generally to other marginalized groups including AIDS patients, drug addicts, the homeless, religious minorities, the LGBTQ community, and women (e.g., Batson et al. Reference Batson, Polycarpou, Harmon-Jones, Imhoff, Mitchener, Bednar, Klein and Highberger1997; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Flores, Haider-Markel, Miller and Taylor2024; Shih et al. Reference Shih, Stotzer and Gutiérrez2013; Sirin et al. Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2017; Tarrant and Hadert Reference Tarrant and Hadert2010; Villalobos and Sirin Reference Villalobos, Sirin, Bailey, Nawara and Floresforthcoming). For instance, those who score high in group empathy are more likely to support the #MeToo movement, higher representation of women in government, and equal opportunity policies for women, as well as more likely to acknowledge systematic discrimination against women (Sirin et al. Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2021).Footnote 7

As a powerful general predisposition, group empathy allows one to experience vicariously the perspectives and emotions of other groups, especially when such groups are subjected to undue burden.Footnote 8 In the case of overturning Roe v. Wade, those with higher group empathy should be able to better internalize cognitively and affectively the negative ramifications of the Dobbs ruling even if such decision may not bear any direct harm on their own lives. While one’s self-positioning as pro-choice versus anti-abortion is heavily connected to one’s partisanship and ideological orientations, we expect that the main positive effect of group empathy on one’s opposition to Dobbs is significant and independent of those political factors. Accordingly, our first hypothesis posits the following:

H1: Those who score higher in group empathy are more likely to oppose the overturning of Roe v. Wade.

The next two hypotheses focus on the effect of opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade on voter mobilization. As mentioned, the statistics on voter turnout for the 2022 midterms (see U.S. Census Bureau 2023) do not align well with the “Roevember” arguments. As Frey (Reference Frey2023) points out, “Among broad age groups, 18- to 29-year-olds showed a noticeable decline in turnout since 2018, with the oldest group (over age 65) registering a modest gain.” Perhaps even more surprisingly, female turnout also declined slightly in 2022 compared to the 2018 midterms. Nevertheless, the record levels of voter turnout in the 2022 midterms and the failure of the forecasted “Red Wave” vote have been largely attributed to the Supreme Court decision to revoke constitutional protections on abortion rights that occurred a few months prior to the elections. According to such narrative, the mobilizing effect of the Dobbs ruling on voting behavior should have been especially large among the youth and women, thereby presuming self-interest and identity to be the primary motivational mechanisms. Our goal here is to formalize (and in turn empirically test) these widespread propositions as follows:

H2a: Opposition to the overturning of Roe v. Wade motivated campaign participation and voter turnout at the 2022 midterm elections.

H2b: Such opposition mobilized younger voters—especially younger females—more strongly since the elimination of federal constitutional protections on abortion rights affects them most directly as compared to older constituents.

Besides the potential effects of opposing the reversal of Roe v. Wade, we test our own conjecture that there should be a significant, positive direct effect of group empathy on voter mobilization. Equipped with an intrinsic motivation to care about others, those who possess higher levels of group empathy are more likely to actively participate in politics. At the individual level, research on social psychology has consistently shown that empathy leads to pro-social behavior such as volunteerism and donation (Davis Reference Davis, Schroieder and Graziano2015; Decety et al. Reference Decety, Bartal, Uzefovsky and Knafo-Noam2016). Group-level empathy has been linked to even stronger behavioral consequences in the political arena such as attending a rally to support the rights of marginalized groups (e.g., for the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements), signing petitions, and donating to stigmatized groups such as refugees (see Batson et al. Reference Batson, Chang, Orr and Rowland2002; Johnston and Glasford Reference Johnston and Glasford2018; Sirin et al. Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2017, Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2021). In contrast to individuals with high group empathy, we expect those who lack group empathy are likely to demonstrate political apathy and not get involved even during high-stakes elections like the 2022 midterms.

H2c: Group empathy should increase campaign participation and voter turnout.

Going beyond the proposed main effects, we also expect an interaction between group empathy and opposition to the Dobbs decision in predicting one’s voting behavior at the 2022 midterms. Because group empathy is a general predisposition that is particularly invoked when seeing groups in distress, its core element—the motivation to care for others—increases one’s likelihood to act on their opposition to the demise of Roe v. Wade. Devoid of group empathy, mere opposition to the Dobbs ruling may actually be demobilizing for those who lack the motivation to care.

H3a: Group empathy should moderate the effects of opposition to the overturning of Roe v. Wade on campaign participation and voter turnout.

Because the Supreme Court’s decision to roll back federal constitutional protections on abortion rights has more devastating implications for the youth (especially younger women), group empathy as an other-oriented trait should be more effective in mobilizing older constituents who are less likely to be directly harmed. In other words, while the mobilization of younger voters—especially young females—might be primarily out of self-interest and identity, older voters with high levels of group empathy are more likely to be motivated by concern for others in distress. Additionally, political and social/cognitive psychology research finds that women possess higher empathic abilities as compared to men, which leads to significant differences in their attitudes and behavior (see, for example, McCue and Gopoian Reference McCue and Gopoian2000; Sirin et al. Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2021). We would thus expect the moderating effect of group empathy on the link between opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade and voter mobilization to be even larger among older females.

H3b: Given that group empathy is an other-oriented trait, the magnitude of its moderating effects should be larger among older voters—especially older females—since the elimination of federal constitutional protections on abortion rights poses more harm to younger constituents.

Data and Research Design

We employed data from a nationally representative survey to test our hypotheses. In March 2023, YouGov interviewed 1,072 respondents who were then matched down to a sample of 1,000 to produce the final dataset. The respondents were matched to a sampling frame on gender, age, race, and education. The sampling frame is a politically representative “modeled frame” of U.S. adults, based on the American Community Survey (ACS) public use microdata file, public voter file records, the 2020 Current Population Survey (CPS) Voting and Registration supplements, the 2020 National Election Pool (NEP) exit poll, and the 2020 CES surveys, including demographics and the 2020 presidential vote. The matched cases were weighted to the sampling frame using propensity scores. The matched cases and sampling frame were combined and a logistic regression was estimated for inclusion in the frame. The propensity score function included age, gender, race/ethnicity, years of education, and region. The propensity scores were grouped into deciles of the estimated propensity score in the frame and post-stratified according to these deciles. The weights were then post-stratified on the 2020 presidential vote choice, a four-way stratification of gender, age, race, and education, and a two-way stratification of race and education, to produce the final weight.

Our two main outcome variables are voter turnout and campaign participation. Voter turnout was measured as a binary variable based on whether respondents voted or not in the 2022 midterm elections. Campaign participation was an index variable that we created based on a set of items on respondents’ active involvement in the 2022 midterms aside from turning out to vote. These items included whether the respondent: (1) convinced someone else to vote; (2) convinced someone else to vote for their candidate; (3) convinced someone else not to vote for a specific candidate; (4) attended a rally or protest; (5) donated to a campaign; (6) volunteered with a campaign; (7) wore campaign clothing; and (8) put up a candidate sign. Cronbach’s alpha is .75, indicating high internal consistency reliability for this additive scale.

Our main independent variable is group empathy, for which we employed the “Group Empathy Index” (GEI). Similar to its counterpart “Interpersonal Reliability Index” (originally developed by Davis Reference Davis1980) designed to measure individual-level empathy, the GEI has demonstrated high test-retest reliability, as well as construct, content, and predictive validity across multiple time periods, cross-national contexts, and policy issues (Sirin et al. Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2016a, Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2016b, Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2017, Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2021). Prior works conceptualize empathy as a multidimensional construct with cognitive, affective, and motivational aspects (see Davis Reference Davis1980, Reference Davis1983; Reniers et al. Reference Reniers, Corcoran, Drake, Shryane and Völlm2011; Cuff et al. Reference Cuff, Taylor and Howat2016). The GEI captures this multidimensionality in a concise instrument designed to tap one’s general predisposition to display perspective taking abilities and empathic concern for groups (especially for those in distress) with motivation to care embedded in each item.Footnote 9

As displayed in Table 1, the wording “other racial/ethnic groups” is used to capture one’s group-level empathy. In a political context where race and ethnicity are among the most salient social categorizations, the GEI constitutes an effective and efficient measure. Moreover, given the fact that racial/ethnic divisions are often the primary sources of group-based threat, competition, and conflict, framing the items as such allows for a more conservative measure of group empathy. To put it differently, the GEI scores could be more inflated if the GEI items were framed as “other groups in general” rather than “other racial/ethnic groups” because the former is more abstract and might provide less solid ground for situating one’s group-level empathy in responding to the GEI items. Such item wording also helps avoid endogeneity concerns because we employ the GEI to predict gender-related political attitudes and behavior exogenously in its original race/ethnicity-based form in our statistical models. Previous studies—conducted both in the U.S. and Great Britain—have consistently shown that the GEI is a significant predictor of not only race/ethnicity-related political attitudes and behavior, but also policy opinions concerning women and the LGBTQ community (Sirin et al. Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2021).

Table 1. Four-Item Group Empathy Index (GEI)

Note. Response options: (1) Not often at all; (2) Not too often; (3) Somewhat often; (4) Very often; (5) Extremely often.

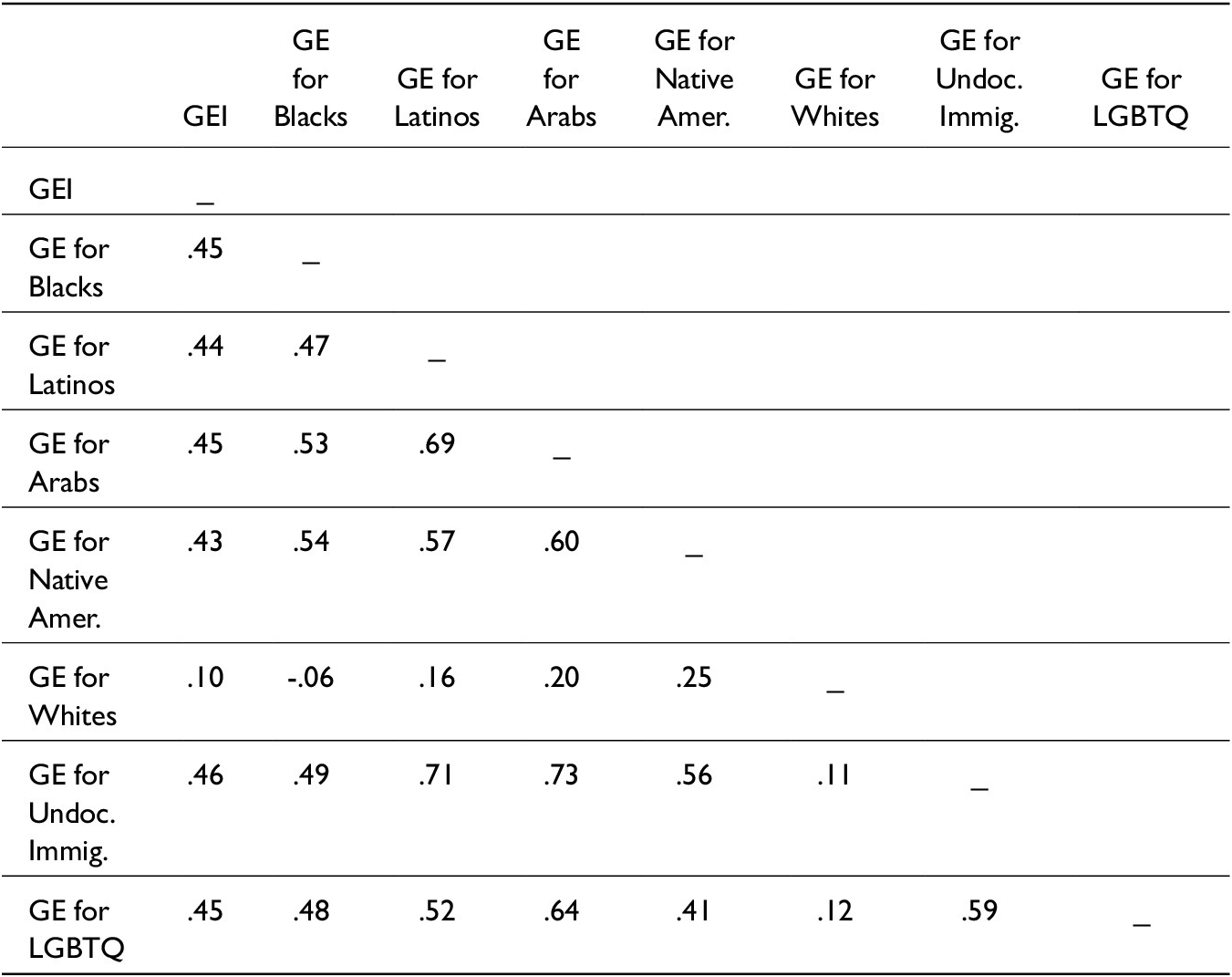

Table 2 presents the correlation matrix for general group empathy measured by the GEI and group-specific empathy for various groups using data from a nationally representative survey of 1,050 participants, conducted in 2018 by YouGov. The correlation between the GEI and group-specific empathy for the LGBTQ community (r = .45) is very high and nearly identical to the correlation between the GEI and group-specific empathy expressed for Blacks (r = .45), Latinos (r = .44), Arabs (r = .45), and Native Americans (r = .43), as well as for undocumented immigrants (r = .46). The only correlation score that is different from other scores in the matrix is the one between the GEI and group-specific empathy for Whites, which is only .10. This analysis indicates that, in line with Group Empathy Theory, group empathy—measured by the GEI—is applied generally to other groups including non-racial/ethnic ones, and especially toward those that are disadvantaged/marginalized rather than those that maintain a dominant status in society.

Table 2. Correlation matrix for general group empathy and group-specific empathy

Note. General group empathy is measured by the Group Empathy Index (GEI).

Source: 2018 Group Empathy Study.

In this particular study, we expect that group empathy as a general predisposition is not only extended towards racial/ethnic minorities but also towards women as a political minority in distress having lost their constitutional right to bodily autonomy and access to reproductive care. Group empathy may be especially triggered in reaction to the disproportionately heavier burden that falls on minority women who had already been suffering from higher maternal morbidity and mortality rates and, more generally, low-income females who now have even fewer resources and options for dealing with post-Dobbs restrictions to reproductive care (Fuentes Reference Fuentes2023; Treder et al. Reference Treder, Amutah-Onukagha and White2023).

The other main variable is one’s opposition to the overturning of Roe v. Wade, which we measured using an ordinal 5-point scale that ranged from “strongly support” to “strongly oppose.” We also control for the effects of party identification (7-point scale ranging from strongly Democrat to strongly Republican) and ideology (5-point scale ranging from strongly liberal to strongly conservative) because they are expected to be primary drivers of voting behavior as well as attitudes about abortion rights. Our models also include key socio-demographic and economic factors including gender, race/ethnicity, age, education, household income, and church attendance. In addition to our original models, we ran sensitivity analyses with more parsimonious models (excluding party identification and ideology)Footnote 10 as well as expanded models with a larger set of control variables including religiosity, religious identification as Catholic, marital status, having children under 18, employment status, and whether respondents knew someone who had an abortion. The results reported in the next section are robust to these alternative model specifications.Footnote 11

Females constituted 55% of the sample. About 67% of respondents identified as White. About 46% of respondents held a college or higher degree. As for party affiliation, 36% identified as Republican while 43% identified as Democrat. All variables are linearized to run from 0 to 1 for ease of comparison. We used sampling weights provided by YouGov in our statistical analyses of the survey data.

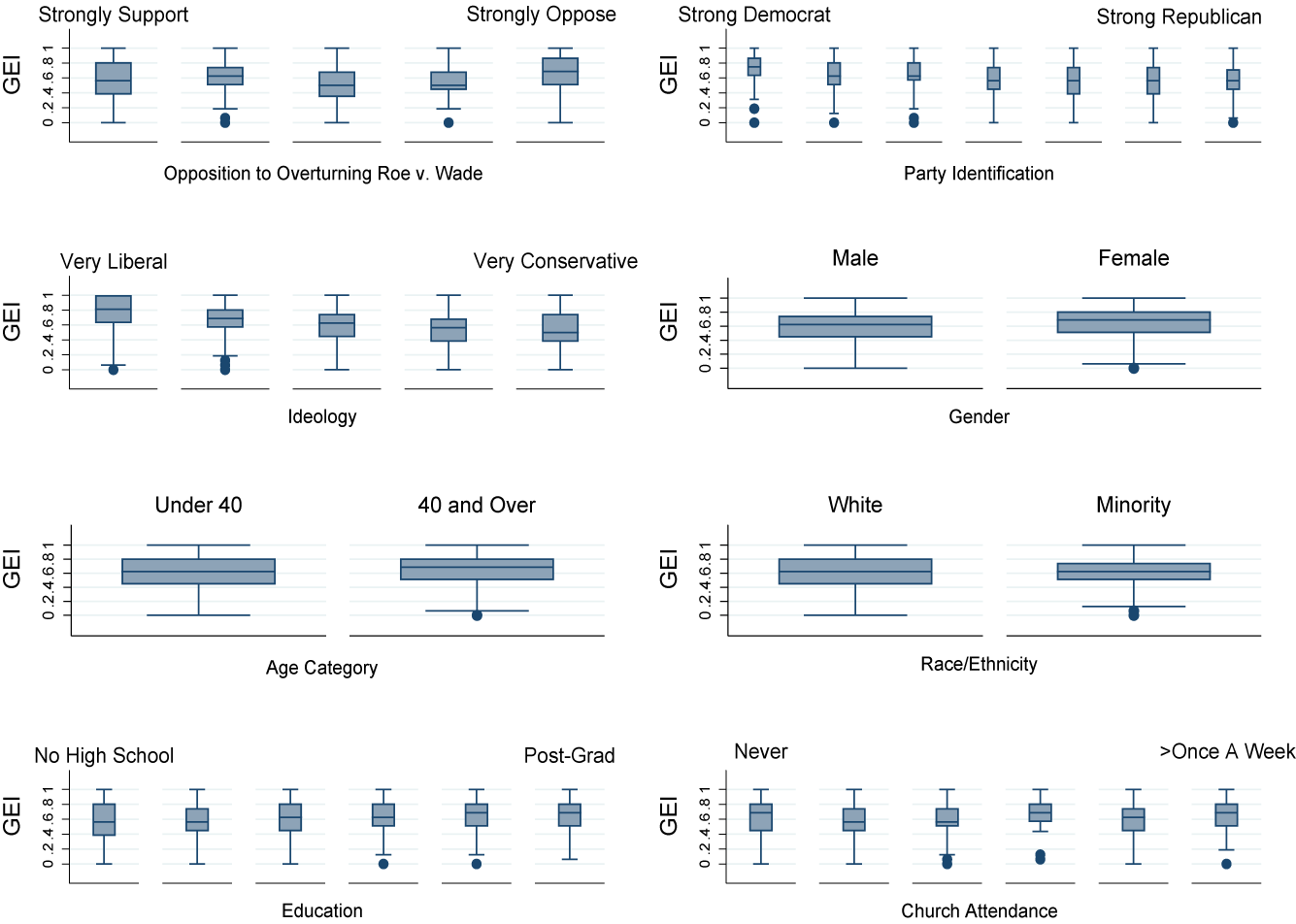

Figure 2 provides box plots of the distribution of the GEI across key political and socio-economic groups in the sample. Strong liberals and Democrats, as well as those who strongly oppose Dobbs are at the higher end of the scale as theoretically expected, and yet there is still a relatively balanced distribution across each category. Further analyses of the sample data show that the GEI does not correlate highly with neither party identification (r=-.20) nor ideology (r=-.24), and its simple pairwise correlation with opposition to Dobbs is positive but low (r=.13)—corroborating the validity of the GEI as an independent construct.Footnote 12 Moreover, consistent with previous research (e.g., Sirin et al. Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2021), the box plots indicate higher means for the GEI among females, older voters, and the more educated.

Figure 2. The distribution of the GEI in the sample.

Note. Box plots of the distribution of the GEI across key political and socio-economic groups. All variables are linearized to run from 0 to 1.

Source: 2023 Group Empathy Study.

Meanwhile, unsurprisingly, opposition to the overturning of Roe v. Wade is highly correlated with party identification (Democrat-Republican), ideology (Liberal-Conservative), and church attendance with r-values of -.45, -.54, and -.44 respectively. Also expectedly, party identification and ideology are highly correlated (r=.65). Another expected correlation is between income and education (r=.47). Given these correlation coefficients, we checked for potential multicollinearity issues by conducting a variance inflation factor (VIF) test. Table 3 shows that the mean VIF is 1.44 and none of the variables surpass 2.5, which is well below the critical threshold of 10 (or an even more conservative benchmark of four) that would indicate serious multicollinearity problems (Gujarati and Porter Reference Gujarati and Porter2009).Footnote 13 Given the results of the multicollinearity checks, we decided to keep all of the key independent variables in our models to avoid any potential omitted variable bias in our statistical estimates.

Table 3. Multicollinearity checks

Note. Data are weighted.

Source: 2023 Group Empathy Study.

Results

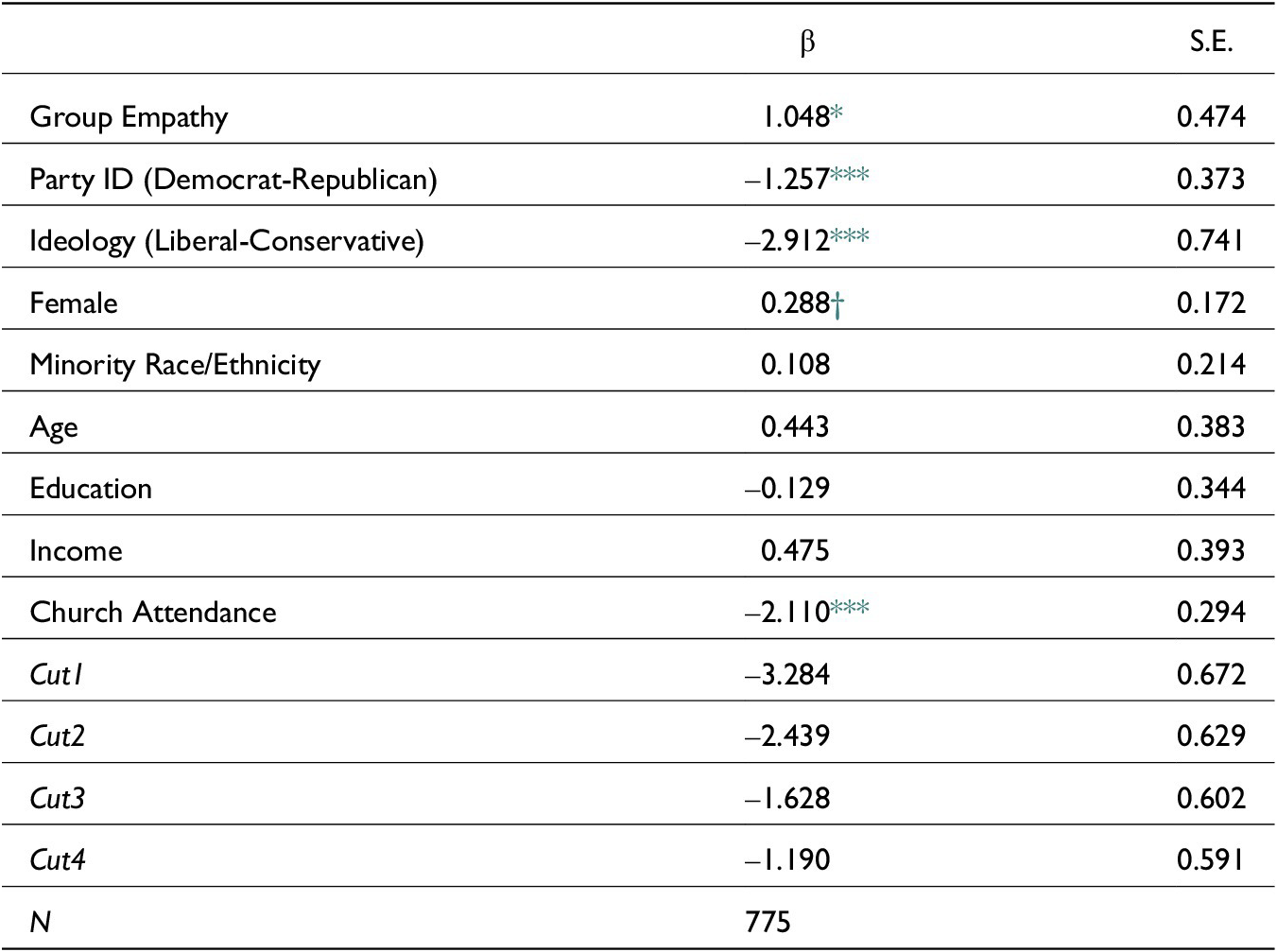

We first examined whether group empathy is a significant driver of public reactions to the overturning of Roe v. Wade. The results of the ordered logistic regression analysis (displayed in Table 4) demonstrate that those who score higher in the GEI are indeed more likely to oppose the SCOTUS decision to overturn Roe v. Wade (p < .05). Expectedly, conservative ideology and church attendance are the top two predictors of support for the Dobbs ruling. That said, the coefficient size of group empathy (1.048) is almost as large as party identification (-1.257), and the predicted probability of “strongly opposing” the overturning of Roe v. Wade doubles from .25 to .50 as one moves from the lowest to highest level of group empathy. These results corroborate our first hypothesis.

Table 4. The effect of group empathy on one’s opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade

Note. Coefficients estimated via ordered logistic regression. Data are weighted. All variables in the models are linearized to run from 0 to 1.

† p ≤ .10

* p ≤ .05

** p ≤ .01

*** p ≤ .001, two-tailed.

Source: 2023 Group Empathy Study.

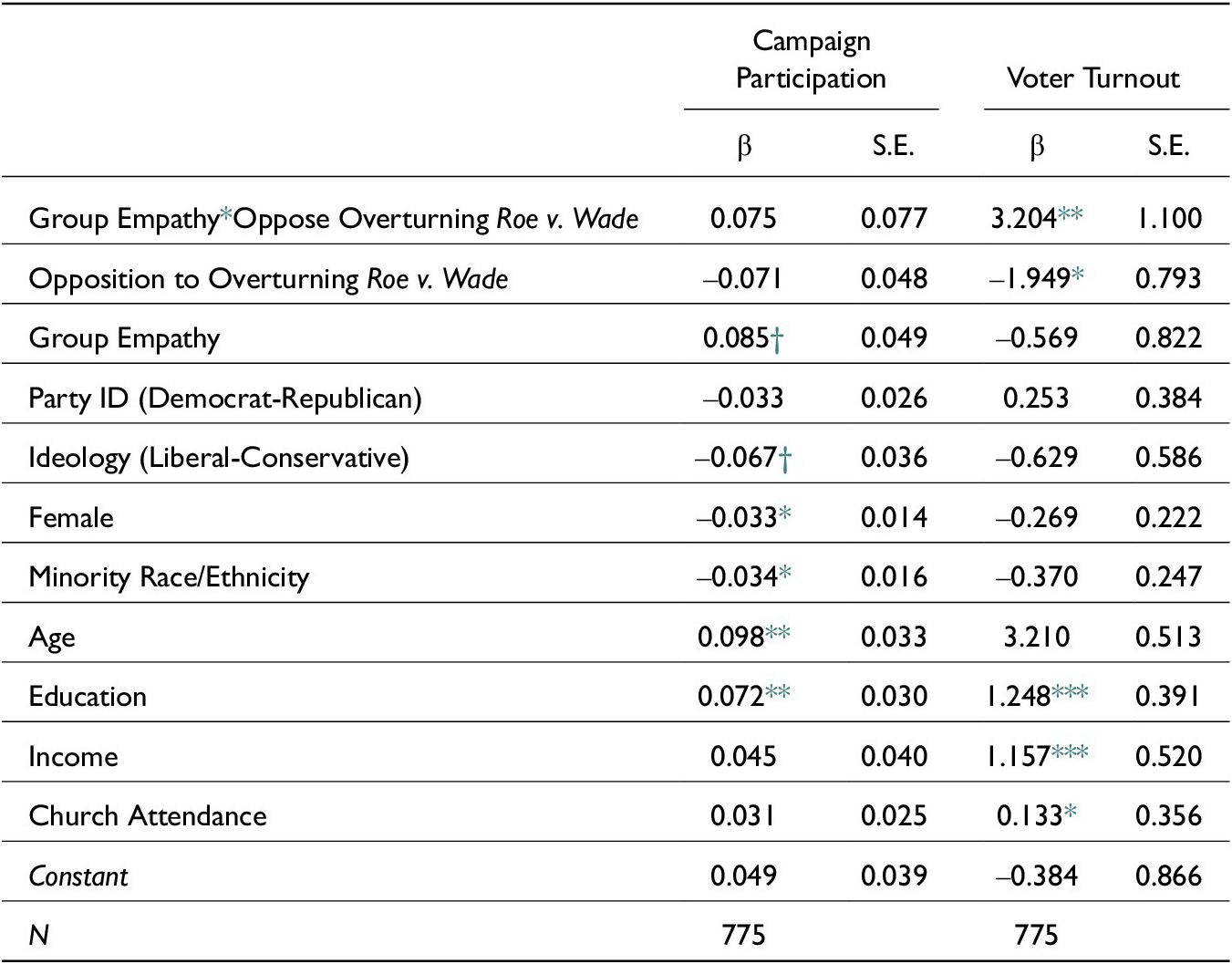

The second set of analyses was conducted to test empirically whether opposition to the overturning of Roe v. Wade was sufficient on its own to drive voter mobilization in the 2022 midterm elections as commentators and pundits speculated (displayed in Table 5). As we suspected, attitudes about the Supreme Court ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade were not statistically linked to neither campaign participation nor voter turnout (p > .10).Footnote 14 Therefore, we found no support for Hypothesis 2a.Footnote 15

Table 5. The main effects of opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade and group empathy on voter mobilization

Note. Coefficients for campaign participation estimated via OLS regression and for voter turnout via binary logistic regression. Data are weighted. All variables in the models are linearized to run from 0 to 1.

† p ≤ .10

* p ≤ .05

** p ≤ .01

*** p ≤ .001, two-tailed.

Source: 2023 Group Empathy Study.

We next tested Hypothesis 2b, which formalizes the mainstream speculation that opposition to the overturning of Roe v. Wade powerfully mobilized young voters—especially younger females—because the elimination of federal constitutional protections on abortion rights affects them more directly than older constituents. As such, this conjecture denotes self-interest and identity as the primary motivational mechanisms for voter mobilization in reaction to the SCOTUS decision. For this test, we interacted attitudes about the Dobbs ruling with gender and age (categorized by those under 40 versus those 40 and over).Footnote 16 Regarding campaign participation, we find no significant three-way interaction of opposition to Dobbs, age, and gender (p > .10). As illustrated in the top row of Figure 3, levels of opposition to Dobbs did not yield any shift in campaign participation among females in either of the age groups while male voters (particularly older men) who strongly opposed the Dobbs ruling were somewhat less politically active during the campaign season than those who strongly supported Dobbs. Footnote 17

Figure 3. The interactive effects of opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade, gender, and age on voter mobilization

Note. Lines represent the marginal effects of opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade on one’s campaign participation (OLS regression) and probability to vote (logistic regression) among males vs. females grouped by those under and over 40, with controls for group empathy, party identification, ideology, race/ethnicity, education, income, and church attendance. The shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Source: 2023 Group Empathy Study.

As for voter turnout, we found a statistically significant three-way interaction (p < .05), but it does not align well with H2b either. As visualized in the second row of Figure 3, older males who strongly supported Dobbs were much more likely to vote compared to younger ones, but the probability to vote was statistically equal among males who strongly opposed Dobbs regardless of their age. In this respect, one’s level of opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade mobilized younger males to vote, but not enough to surpass older males. The results further show that older females were overall more likely to vote in the 2022 midterms than younger ones. Moreover, attitudes about the Dobbs ruling did not generate a major shift in one’s probability to vote among older females. Perhaps most interestingly, a downward slope among younger females indicates that those who strongly opposed Dobbs were actually less likely to vote (.53) compared to younger females who strongly supported Dobbs (.69). These results are inconsistent with the mainstream expectations formulated in H2b.

Referring to Table 5, a comparison of coefficient sizes estimated by the OLS regression model for campaign participation points to group empathy as the top driving factor for one’s likelihood to participate in the election campaign (.12; p < .001), even above and beyond party identification and ideology (-.03 and -.07 respectively). The effect of group empathy is also significant on voter turnout, both statistically and substantively. One’s probability to vote increases by more than 18 percentage points as the GEI moves from its lowest to highest value. These findings are in line with Hypothesis 2c. The results further indicate that the primary driver of voting was age with higher turnout observed among older constituents (p < .001). So even though a large number of young voters went to the ballot box at the 2022 midterm elections, their turnout rates were still lower than the older generations. Consistent with the literature on electoral behavior, those with higher education and income levels were also significantly more likely to vote.

The next set of analyses (presented in Table 6) explores the interactive effects of group empathy and opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade on voter mobilization. A regression model that included an interaction between these two variables on campaign participation yielded no statistically significant results (p > .10). On the other hand, the two-way interaction model for voter turnout was statistically significant (p < .01). This indicates that, as predicted in Hypothesis 3a, group empathy does indeed moderate the effect of opposition to the Dobbs ruling on voter turnout. While such opposition on its own did not exert any direct effect on one’s likelihood to vote, it did demonstrate a significant interaction effect moderated by one’s level of group empathy.

Table 6. The interactive effects of opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade and group empathy on voter mobilization

Note. Coefficients for campaign participation estimated via OLS regression and for voter turnout via binary logistic regression. Data are weighted. All variables in the models are linearized to run from 0 to 1.

† p ≤ .10

* p ≤ .05

** p ≤ .01

*** p ≤ .001, two-tailed.

Source: 2023 Group Empathy Study.

We graph this interaction to map out the precise manner that group empathy moderated the effects of one’s opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade on voter turnout in the 2022 midterm elections. As Figure 4 illustrates, for those who scored lowest on the GEI, such opposition was actually quite demobilizing. Among those who lacked group empathy, the predicted probability to vote was over .8 for the ones who strongly supported the Dobbs decision while it dropped to .44 for those who strongly opposed it. As for respondents who displayed average levels of group empathy, the likelihood to vote was the same (.75) for those who were on opposite sides of the Roe v. Wade issue. Opposition to the overturning of Roe v. Wade had a positive effect on voter turnout only among those who scored high in group empathy with their probability to vote increasing from .71 to .88 as opposition to Dobbs moved from the lowest to highest level. As such, among individuals who strongly opposed overturning Roe v. Wade, those with high group empathy were twice as likely to vote (.88) compared to those who scored low in group empathy (.44).

Figure 4. The interactive effects of opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade and group empathy on voter turnout – all respondents.

Note. Lines represent the marginal effects of opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade on one’s probability to vote under three different levels of group empathy (minimum, mean, and maximum) based on the logistic regression interaction model in Table 6, with controls for party identification, ideology, gender, race/ethnicity, age, education, income, and church attendance. The shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Source: 2023 Group Empathy Study.

These findings align well with the predictions of Group Empathy Theory suggesting that one’s motivation to care for groups in distress is a catalyst for political action. On the other hand, those who lack such motivation also lack the drive to act on their political convictions. Indeed, some pro-choice voters might have felt defeated by the overturning of Roe v. Wade. Given the Supreme Court’s current conservative super-majority with life tenure terms, some might have become extremely demoralized and pessimistic about any prospects for regaining federal constitutional protections in the foreseeable future. Lacking empathic motivation, these voters might have instead felt apathetic about abortion politics, especially since such a consequential SCOTUS ruling on federal protections could not simply be overridden at the voting booth.

We further explored the moderating effects of group empathy on the link between opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade and voter mobilization by comparing male versus female respondents under 40 years of age with those 40 and older. The top row of Figure 5 presents the interaction graphs for campaign participation in the 2022 midterms. We see no statistically significant differences in campaign participation across group empathy levels for neither younger nor older males who strongly opposed overturning Roe v. Wade. Footnote 18 Meanwhile, younger and older females with high group empathy are both much more politically active as opposition to Dobbs increases. However, the moderating effect of high group empathy on campaign participation among older females is larger and statistically distinct from not only those who score low in group empathy but also from those displaying average levels of empathy. Meanwhile, a steeper downward slope of low group empathy for women under 40 indicates that lacking empathy for groups in distress is particularly demobilizing in this age category.

Figure 5. The moderating effects of group empathy on the link between opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade and voter mobilization – comparing males vs. females under and over 40.

Note. Lines represent the marginal effects of opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade on one’s campaign participation (OLS regression) and probability to vote (logistic regression) under three different levels of group empathy (minimum, mean, and maximum) among males vs. females grouped by those under and over 40, with controls for party identification, ideology, race/ethnicity, education, income, and church attendance. The shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Source: 2023 Group Empathy Study.

The bottom row of Figure 5 displays one’s likelihood of voting in the 2022 midterms based on opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade across low, mean, and high levels of group empathy among males versus females under 40 and those 40 and older. Among both younger and older males, the probability to vote is statistically indistinguishable (given 95% confidence intervals overlapping) across different levels of group empathy. For men under 40, stronger opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade corresponds to a higher likelihood of voting irrespective of one’s level of empathy for groups in distress. Among older males, high empathy somewhat increases one’s probability of voting while low empathy is demobilizing as one moves from strongly supporting the Dobbs decision to strongly opposing it—a pattern more closely aligned with our theoretical expectations (but not statistically significant). By comparison, the moderating effects of group empathy are statistically and substantively significant for both younger and older female respondents. The results show that low empathy was drastically demobilizing for women who opposed the overturning of the Roe v. Wade. As one moves from strongly supporting the Dobbs decision (0) to strongly opposing it (1), the predicted probability of voting drops from .63 to only .05 for women under 40 and from .90 to .34 for women 40 and over among those who scored low in group empathy. On the other hand, those who scored high in the GEI were significantly more likely to show up at the polls in the 2022 midterms if they strongly opposed the Dobbs ruling. Among those with high group empathy, the predicted probability of voting increases from .75 to .85 for women under 40 and from .76 to .94 for older women moving from the lowest to highest level of opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade.

Overall, these findings lend mixed support to Hypothesis 3b. The moderating effects of group empathy on voter mobilization among older males with higher levels of opposition to the Dobbs ruling is not statistically significant—albeit in the expected direction for turnout. Among females, group empathy exerts statistically significant and substantive interactive effects in the expected direction on both campaign participation and voter turnout. Yet, somewhat surprisingly, the magnitude of these moderating effects is not much larger among women over 40 compared to their younger counterparts. It is particularly noteworthy that group empathy as a general predisposition significantly moderated even the mobilization patterns of younger women who were portrayed to vote primarily out of self-interest and identity in the 2022 midterms in reaction to the overturning of Roe v. Wade. The substantive motivational effects of group empathy on women’s voting behavior remains consistent with prior findings that women generally display higher empathy for distressed others in society at both the individual and group levels (e.g., McCue and Gopoian Reference McCue and Gopoian2000; Sirin et al. Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2021).

Robustness Check: The 2020 Presidential Elections

As a robustness check, we analyzed the main and interactive effects of group empathy and abortion rights attitudes on voter mobilization in the context of the 2020 presidential elections using data from the American National Election Studies (ANES). The 2020 U.S. presidential election between Joe Biden and Donald Trump had the highest voter turnout (66.3% of eligible voters) in the last 120 years despite a raging pandemic (see Schaul et al. Reference Schaul, Rabinowitz and Mellnik2020). While the election took place before the 2022 Dobbs ruling, the stakes were already high for supporters of abortion rights given Trump’s appointment of three pro-life conservative Justices to the Supreme Court, which had greatly shifted the ideological balance of the Court. In these 2020 ANES models, we keep all the independent variables (including the 4-item GEI) essentially the same except for “opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade,” which we replaced with one’s level of support for abortion rights that ranged on a 4-point scale from support for a total abortion ban to unconditional support for a woman’s right to choose.Footnote 19 As for the dependent variables, we created an index of campaign participation (almost identical to the one we used in our main analyses)Footnote 20 and measured voter turnout as whether or not the respondent voted in the 2020 election.

The 2020 ANES results (provided in the Supplementary Materials) are consistent with our empirical findings using the 2023 YouGov data. Group empathy, measured by the GEI, was a significant main predictor of both campaign participation and voter turnout in the 2020 presidential elections while support for abortion rights was not. The interaction patterns are also very similar to the ones we observe in the analyses of the 2022 midterm elections. In the 2020 ANES, we find a significant interaction between group empathy and support for abortion rights not only for voter turnout but also for campaign participation. As levels of support for abortion rights increased, those who scored high in empathy for groups in distress also scored higher in campaign participation and were more likely to vote. Meanwhile, those who fully supported abortion rights but lacked group empathy were substantively less likely to participate in the election campaign and less likely to vote. These results pertaining to the 2020 presidential elections are thus in line with our theoretical conjecture about the motivational drive group empathy exerts on political action, in this case voter mobilization potentially prompted by support for women’s abortion rights.

What About Vote Choice?

On a final note, while campaign participation and voter turnout constitute the key outcomes this study has focused on, some may wonder how our main variables related to vote choice in the 2022 midterms. To provide some preliminary insights on this, we conducted cursory analyses by running our regression models using vote choice as the outcome variable. The survey asked those respondents who had confirmed voting in the 2022 midterm elections whether they voted (on a 5-point scale) “entirely for Democrats, mostly for Democrats, about equally for Democrats and Republicans, mostly for Republicans, or entirely for Republicans.” The results (available in the Supplementary Materials) show that, unsurprisingly, opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade had a significant and substantive direct effect on one’s likelihood of voting for Democrats. Group empathy also had a significant main effect on Democratic vote choice even after controlling for party identification (which, of course, proved to be the primary determinant for this outcome variable) as well as ideology.

As for the interaction effects, the observed pattern was different from campaign participation and voter turnout when it came to vote choice. Those with low group empathy who did not oppose Dobbs were much less likely to vote for Democrats as compared to those with high group empathy while stronger opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade motivated both high and low empathizers to vote for Democratic candidates once people went to the ballot box. These results warrant further investigation into the direct and indirect effects of group empathy and support for abortion rights on voting behavior in future elections.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, we empirically examined the effects of public reactions to the overturning of Roe v. Wade on voter mobilization. Despite widespread speculation that portrayed the results of the 2022 midterm elections as a referendum vote against the Supreme Court’s contentious Dobbs v. Jackson WHO ruling, we find that opposition to overturning Roe v. Wade did not directly influence overall campaign participation or voter turnout. Instead, only those high in empathy for groups in distress were significantly mobilized to act on their opposition to the elimination of women’s constitutional right to choose. We thus find that group empathy was a powerful force in shaping the 2022 midterm elections.

These results provide a snapshot of what happened in the immediate aftermath of the Dobbs decision. One should keep in mind that the 2022 midterm elections took place only a few months after the Supreme Court’s ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade. Though the undue burden on women caused by the controversial decision at the time appeared obvious and trigger laws in several states had begun to severely impact women at the individual level (see McCann and Schoenfeld Walker Reference McCann and Walker2024), it would take longer for the wider public to internalize the full legal, political, social, and personal ramifications of the ruling. Since then, many horror stories have ensued and garnered media attention raising public awareness. For example, even in cases where a mother’s life is at risk, many health care providers in states that adopted severe abortion restrictions and bans became highly hesitant and overly cautious in medically intervening to terminate a pregnancy for fear of criminal prosecution. In one particular instance, an Oklahoma woman, Jaci Statton, with a molar pregnancy (which was non-viable and cancerous), was told by the hospital to wait in the parking lot until her condition deteriorated enough to qualify for an emergency abortion (see Simmons-Duffin Reference Simmons-Duffin2023). As Statton recounted, “They said, ‘The best we can tell you to do is sit in the parking lot, and if anything else happens, we will be ready to help you. But we cannot touch you unless you are crashing in front of us or your blood pressure goes so high that you are fixing to have a heart attack’” (Simmons-Duffin Reference Simmons-Duffin2023). In another instance that caught the national spotlight, the Texas Supreme Court ruled against a Texan mother of two, Kate Cox, who had requested an abortion exception after her fetus was diagnosed with a fatal genetic condition that also jeopardized her future fertility and caused medical complications (Kitchener and Vazquez Reference Kitchener and Vazquez2023). Cox eventually chose to go out of state to receive the medical care she needed. In yet another high-profile case, a 10-year-old rape victim had to travel from Ohio to Indiana to terminate her pregnancy (Burga Reference Burga2022). Many girls and women in similar situations seek abortion care in other states if their health and financial means allow for such travel. In some states, women need to travel for more than eight hours to access abortion care (Rader et al. Reference Rader, Upadhyay, Neil, Reis, Brownstein and Hswen2022).

A report from the Gender Equity Policy Institute indicates that women residing in states with abortion bans are almost three times more likely to die during pregnancy, childbirth, or soon after giving birth (González Reference González2023). Additionally, research shows that abortion bans across the country have been disproportionately affecting women of color and low-income women (see Paltrow et al. Reference Paltrow, Harris and Marshall2022; Räsänen et al. Reference Räsänen, Gothreau and Lippert-Rasmussen2022). As Abrams (Reference Abrams2023) notes, “More than 60% of those who seek abortions are people of color and about half live below the federal poverty line, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive health research and policy group. And many people of color, including the majority of Black Americans, live in Southern states with some of the most restrictive abortion laws.” Even before the 2022 Supreme Court ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade, there were severe racial/ethnic disparities in terms of access to reproductive care as well as with respect to maternal morbidity and mortality rates (Luna Reference Luna2020; Signore et al. Reference Signore, Davis, Tingen and Cernich2021). These existing inequities have been further exacerbated since the Dobbs decision (Fuentes Reference Fuentes2023; Treder et al. Reference Treder, Amutah-Onukagha and White2023).

The direct and moderating effects of group empathy have likely grown even stronger over time as people continue witnessing either first-hand or through news stories how the Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe is harming women’s lives. We also think it is quite plausible that one’s opposition to the overturning of Roe v. Wade will have a stronger direct effect in the elections to come as the devastating consequences of the Dobbs ruling become more and more evident. We will continue our empirical investigations in this vein so we can track longitudinally the patterns discovered here. We should note that while the survey employed in this study is nationally representative with a large sample size, we also acknowledge the limitations of observational data—especially with respect to causal inference and certain biases such as nonresponse and social desirability (see, for example, Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, Lelkes and Malka2021; Cavari and Freedman Reference Cavari and Freedman2023). Accordingly, our future investigations will also involve collecting behavioral data via experimentation to further document the causal pathways interlinking abortion attitudes, group empathy, and voting behavior.

The contextual focus of this study was the role group empathy played in shaping voting behavior at the 2022 midterm elections in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade. We further think the conjectures of Group Empathy Theory and our empirical findings should apply well to other similar group-based policy arenas with potential electoral implications. For instance, over the past few years, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito repeatedly signaled that the 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges landmark ruling on same sex marriage may be next in line for reconsideration (VanSickle Reference VanSickle2024). While at the time of this writing, there is no solid indication that the Supreme Court will initiate action to overturn the Obergefell v. Hodges ruling (see Acquisto Reference Acquisto2024), those who support the LGBTQ rights remain concerned about this prospect since the conservative justices on the Supreme Court maintain an overwhelming 6-3 majority (see Conley Reference Conley2024). The Supreme Court has also engaged in various other controversial decisions on group-related policies including striking down affirmative action in higher education by effectively ending race-conscious admission programs at colleges and universities across the country (Totenberg Reference Totenberg2023). Each of these developments merit further scholarly investigation. All in all, group empathy offers a novel and increasingly relevant path that goes beyond conventional accounts to explore the attitudinal and behavioral consequences of such political developments, especially those that are tied to marginalized groups.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X24000412.

Acknowledgements

We would like to give special thanks to Nick Valentino from the University of Michigan for generously providing data and feedback for this project. We would also like to thank Danny Choi, Katherine Cramer, Mandi Bates Bailey, and the anonymous reviewers for their support and invaluable suggestions.

Funding Statement

The authors received no funding for this project.

Competing Interest

The authors declare none.