Gender-based violence (GBV) encompasses a variety of acts directed mostly toward women and girls, such as intimate partner violence (IPV), sexual violence, and sex trafficking. Among all forms of GBV, IPV is the most common, affecting one in three women globally (UNODC 2020). While men and boys account for 80% of all homicide victims around the world, women bear a disproportionate burden of lethal violence perpetrated within the home: women accounted for 68% of all victims of intimate partner homicide in 2020 (UNODC 2020). The negative effects of GBV on women are well documented, including ill health, increased fear, emotional distress, suicidality, and long-term effects for children witnessing violence (e.g., Fearon and Hoeffler Reference Fearon and Hoeffler2015; Jordan, Campbell, and Follingstad Reference Jordan, Campbell and Follingstad2010). In short, GBV is a global problem with massive implications for women’s lives and for society at large.

In the 1990s, countries increasingly began to adopt legislation to tackle GBV (e.g., Brysk Reference Brysk2018). While implementation of GBV laws tends to be grossly insufficient (e.g., Neumann Reference Neumann2017), many countries have applied policy frameworks to address the negative consequences of GBV victimization (e.g., UN Women 2012). For example, it is estimated that the Brazilian central government spent 27.5 million reais on anti-GBV programs in 2019; this estimate excludes women’s police stations and other local programs (Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues2020). However, we know very little about people’s evaluations of government efforts to combat GBV. While recent work sheds light on IPV survivors’ evaluations of GBV policies (Kras Reference Kras2022), it is still unclear how people who have not experienced IPV firsthand form opinions about these efforts. This is an important question because nonvictims make up most of the public, and it is their support for mitigating policies that is most crucial for continued funding. Indeed, recent research shows that public opinion on GBV can be a determining factor in the level of implementation of policy instruments for victims at the local level (Araújo and Gatto Reference Araújo and Malu2022). Studies in other policy areas also find that perceptions of policy effectiveness are crucial for approval and support for further policy change (e.g., Drews and van den Bergh Reference Drews and van den Bergh2016). Therefore, this article seeks to fill an important gap in the literature.

How people form evaluations of public policies has been studied extensively by scholars across different policy domains. Like many other political opinions, evaluations of criminal justice policies tend to be formed through various pathways, such as personal and vicarious experiences with authorities (e.g., Karim Reference Karim2020; Mondak et al. Reference Mondak, Hurwitz, Peffley and Testa2017), as well as information gained through media outlets via framing, priming, and learning (e.g., Mullinix, Bolsen, and Norris Reference Mullinix, Bolsen and Norris2021). A central judgment affecting evaluations of criminal justice issues is whether they are deemed to be fair. As documented by a large body of research, fairness evaluations can be based on either distributive fairness—that is, whether the outcomes of policies are viewed as fair—or procedural fairness—whether the process by which decisions are made are perceived as fair (e.g., Peffley and Hurwitz Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2010; Tyler Reference Tyler2001). Crucially, much less is known about whether citizens use information about victims’ experiences with procedural fairness to evaluate policies designed to combat GBV specifically.

In this article, I examine how information about victims’ experiences with the criminal justice system shapes nonvictims’ judgments of broader state efforts to combat this problem. Because this is a policy area in which most people have no direct personal experience,Footnote 1 I theorize that information about the fairness of procedures in GBV victims’ encounters with the police will be a powerful consideration in evaluations of state efforts to combat GBV. The procedural fairness thesis posits that when citizens’ interactions with state agents are perceived as unfair, they are more likely to develop negative views about the state’s policies and authorities (e.g., Peffley and Hurwitz Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2010; Tyler Reference Tyler2001). This is especially true for GBV policies because most citizens have incomplete information about them, making their opinions more malleable. Scholars have demonstrated that procedural fairness should be a particularly important consideration when people experience uncertainty because one might not know what to expect from that situation (Lind and Van den Bos Reference Lind and Van den Bos2002; Van den Bos, Wilke, and Lind Reference Van den Bos, Wilke and Lind1998). Consequently, because IPV victims should have more information about the effectiveness of the state’s efforts to address GBV, they should have substantially stronger attitudes on this issue (e.g., Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2012). Accordingly, victims’ opinions on such policies should be less susceptible to change based on new information about other victims’ experiences compared with nonvictims.

I test my hypotheses using original experiments embedded in public opinion surveys administered in Brazil in 2021. Brazil is an especially appropriate case for examining this research question because GBV has been a salient women’s rights issue for years (e.g., Santos Reference Santos2010). Importantly, Brazil has adopted several innovative public institutions for survivors, such as women’s police stations, which are not only well known by the public but also have been shown to shape more general evaluations of the police (Córdova and Kras Reference Córdova and Kras2020). Even so, Brazil still struggles with high rates of GBV (e.g., Brysk Reference Brysk2018). The experimental manipulations of this study focused on victims’ experiences at a women’s police station. I then analyze the treatment effects of IPV victims’ experience with procedural fairness/unfairness on evaluations of the government’s job in supporting victims and of GBV laws more broadly.

The empirical analysis supports many of my theoretical expectations. Respondents who learned about an IPV victim’s experience with unfair procedures in seeking help from public services were significantly more critical in their evaluations of the performance of the government’s support for victims and of GBV laws in general. Mediation analysis confirms that views of procedural fairness are critical in explaining these effects. However, contrary to my expectations, IPV survivors were not less susceptible to treatment manipulations than nonvictims. I consider the implications of this finding in the discussion of results.

In addition, I also examine whether these attitudes translate into an especially important behavior: bystander intervention. I find that while the procedural unfairness treatment did not lead to detectable changes in people’s willingness to call upon a women’s police station if they had witnessed IPV, it did prompt individuals to be more open to informal channels. In particular, those in the unfair procedures treatment were much more likely than the control group to indicate that they would seek assistance through informal channels, by contacting friends and family. This result suggests that attitudes toward state efforts to combat GBV can translate into behaviors as well.

All in all, this study joins others in demonstrating the importance of procedural fairness for the formation of attitudes. Lack of procedural fairness was particularly damaging for people’s performance evaluations of state efforts in addressing IPV in Brazil, with consequences for how they would intervene in a case of IPV. These results suggest that information about victims’ negative experiences with public services designed to serve them, can offset the positive effects that their existence has on political attitudes (e.g., Córdova and Kras Reference Córdova and Kras2022).

Formation of Attitudes about State Efforts to Combat IPV

Research suggests that public policies disseminate the types of information that people use when forming an opinion on a given issue (e.g., Campbell Reference Campbell2012). New or salient information about policies can influence the public’s belief that the government shares responsibility for outcomes/performance in that domain (e.g., Campbell Reference Campbell2012). As a result, when asked to provide an opinion about a subject related to policy, individuals rely on a “top of the head” process by which they derive an opinion about the policy based on the most salient considerations that come to mind when asked about the issue (Zaller Reference Zaller1992).

Following the enactment of GBV laws and the implementation of necessary services at the local level, citizens have incomplete information regarding this issue as it had been considered private, and therefore outside the government’s domain, for a long time.Footnote 2 Legislation seeking to combat various forms of GBV requires the creation of public services at the local level, such as women’s police stations, crisis centers, and shelters. These institutions can generate feedback effects on the public, fostering a belief that the government should respond to GBV. Visible institutions might generate positive evaluations of state efforts to combat GBV (e.g., Campbell Reference Campbell2012).

Indeed, Córdova and Kras (Reference Córdova and Kras2022) find that men are more likely to express intolerance toward GBV and support bystander intervention by calling the police in municipalities in Brazil that have established women’s police stations—an institution designed to combat GBV specifically. In the case of Brazil, the existence of women’s police stations generates higher trust in the police among women (Córdova and Kras Reference Córdova and Kras2020). These studies suggest that institutions that send strong signals to people about the criminal nature of GBV generate important feedback effects on attitude formation. That is, public policies themselves can shape mass behavior—as shown by Weaver and Lerman (Reference Weaver and Lerman2010) and Mullinix, Bolsen, and Norris (Reference Mullinix, Bolsen and Norris2021) in the case of the criminal justice system in the United States. In the case of GBV, public policies can shape social norms through a learning mechanism in the long run that results in more deep-rooted attitudes critical of GBV (Córdova and Kras Reference Córdova and Kras2022).

However, the average person operates in an environment of incomplete information regarding the effectiveness of these institutions designed to respond to GBV. People might rely on signals from these policies to form opinions about how serious GBV is and whether the state should be responsible for it, but most people have limited information about how they function in practice. Knowledge of the existence of institutions for survivors, like women’s police stations, does not reveal information about their actual effectiveness. What happens when people learn about survivors’ experiences accessing these public institutions? Do they use this information to draw broader conclusions about the effectiveness of state efforts to combat GBV? I argue that in this environment of uncertainty, information about procedural fairness will be particularly relevant for people in deciding how to judge the government’s performance in addressing GBV.

Procedural Fairness and Attitudes toward the Government’s Performance in Addressing GBV

Extant research on procedural fairness has consistently shown that citizens rely on information derived from fair or unfair processes to form attitudes toward authorities (e.g., Sunshine and Tyler Reference Sunshine and Tyler2003). Procedural justice or fairness, which generally refers to the quality of interpersonal treatment and decision-making, entails providing citizens with rights, treating people with dignity and respect, and providing people with a voice (Tyler Reference Tyler2001). Tyler and Lind (Reference Tyler and Lind1992) suggest that fair processes are valuable because they endure across repeated encounters, while outcomes vary on a case-by-case basis. For example, while people are likely to understand that the police could not arrest an aggressor because of insufficient evidence, they are less likely to tolerate police officers who acted in a demeaning way toward a woman seeking help.

Empirical evidence confirms that procedural fairness matters for political opinions. Research has shown, for example, that people’s perceptions of police legitimacy and the fairness of the criminal justice system, in general, are fundamentally linked to perceptions that authorities treat people respectfully (Bell Reference Bell2017; Peffley and Hurwitz Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2010; Tyler Reference Tyler2001). In fact, research suggests that people are concerned with procedural fairness independent of outcomes—or distributive fairness (e.g., Peffley and Hurwitz Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2010). While research has found that individuals might judge the fairness of processes instrumentally (e.g., Biggers and Bowler Reference Biggers and Bowler2021; Esaiasson et al. Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2016), unambiguous violations of principles of fairness lead people to reject them as unfair regardless of the policy outcome (Doherty and Wolak Reference Doherty and Wolak2012). In short, procedural fairness can exert strong effects on a variety of beliefs, feelings, attitudes, and behaviors.

It is worth noting that procedural fairness is an important consideration in domains other than the criminal justice system. For example, studies have shown that people attend to procedural fairness as a way to help them better understand uncertain situations as varied as layoffs, promotions, and evaluations of government processes (e.g., Barclay, Skarlicki, and Pugh Reference Barclay, Skarlicki and Douglas Pugh2005; Doherty Reference Doherty2015; Van den Bos Reference Kees2001). However, given the high stakes associated with the justice realm—which provides a forum for people to obtain safety, solve social conflicts, and claim rights—procedural fairness can be particularly consequential in this policy area. Procedural unfairness can erode people’s evaluation of the entire criminal justice system (e.g., Barkworth and Murphy Reference Barkworth and Murphy2015; Peffley and Hurwitz Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2010) and even engender high levels of cynicism toward the law (Gau Reference Gau2015).

While research exploring the underlying mechanisms connecting procedurally unfair interactions and subsequent attitudes and behaviors remains somewhat underdeveloped (e.g., Demarest Reference Demarest2021), existing investigations suggest that procedural fairness might be operating through emotions. Social psychology researchers have shown that procedural unfairness is uniquely predictive of negative emotions (e.g., anger, indignation, anxiety, resentment; see Barclay, Skarlicki, and Pugh Reference Barclay, Skarlicki and Douglas Pugh2005; Van den Bos Reference Kees2001). Barkworth and Murphy (Reference Barkworth and Murphy2015) further explore this connection by looking at compliance behavior. They find that negative emotions mediate the effect of procedural unfairness and compliance with the police. Moreover, in a series of experiments, Van den Bos (Reference Kees2001) shows that the effect of procedural unfairness on negative emotions is stronger in uncertain conditions. Although an elaborate examination of the role of emotions in procedurally unfair conditions is beyond the scope of this article, I suggest that emotions might still aid in explaining the connection between unfair processes and attitudes toward GBV policies.

Inspired by theories developed by Van den Bos and colleagues, I argue that procedural fairness should be a crucial consideration for individuals when judging the effectiveness of state efforts to combat GBV given the character of the information environment surrounding this policy area. Individuals who have not experienced GBV firsthand might not know what to expect from public institutions for victims of GBV. In environments where GBV is salient, people might hold opinions about the appropriateness of the state’s interference in that policy area. However, nonvictims might not understand the legal remedies and options that victims have well enough to predict an appropriate outcome (distributive fairness) for reaching these state institutions. Similarly, they might be uncertain about the trustworthiness of service providers in these institutions (Van den Bos Reference Kees2001). Scholars suggest that it is precisely in these uncertain circumstances that procedural fairness is particularly useful for making judgments about the authorities (e.g., Lind and Van den Bos Reference Lind and Van den Bos2002). Thus, when confronted with a clear case of an unfair process that a victim has experienced, they can be expected to draw general conclusions about state efforts to prevent and reduce GBV. Moreover, because people assign more weight to negative information (Baumeister et al. Reference Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer and Vohs2001; Mondak et al. Reference Mondak, Hurwitz, Peffley and Testa2017; Van den Bos et al. Reference Van den Bos, Maas, Waldring and Semin2003), evidence of an IPV victim being treated unfairly should have an especially strong impact on their evaluations of government’s performance.

Most people have not personally experienced IPV, and while GBV might be salient as a societal problem, it is not generally perceived as the most important issue of the day.Footnote 3 Research does find that women, on average, are more likely to be critical of GBV and see it as an important issue compared to men (e.g., Córdova and Kras Reference Córdova and Kras2022; Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019). But when salient anti-GBV institutions have been established at the local level, research also finds that men’s probability of rejecting GBV becomes similar to women’s (Córdova and Kras Reference Córdova and Kras2022); institutions can close the gender gap in attitudes toward GBV. However, even if people strongly condemn GBV, they might hold “weak attitudes” about the government’s performance in responding to GBV. This is because even when people are critical of GBV, they might not have complete information on the performance of existing services for survivors. Indeed, individuals tend to hold relatively weak attitudes toward most political issues—constructing their opinions when needed by drawing on accessible considerations about the issue they are evaluating (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2010).

Conversely, stronger attitudes are more resistant to change or persuasion and last longer—“inoculating” individuals from further influence (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2012). Attitudes are more stable when individuals perceive that an issue is linked to one’s rights, privileges, lifestyle, and social group (Boninger, Berent, and Krosnick Reference Boninger, Berent and Krosnick1995). Given their personal experience with abuse, victims of IPV are much more likely to hold stronger attitudes about the government’s performance in responding to GBV. Attitudes that people consider personally important are firmly crystallized and exert a stronger influence on social perceptions and behaviors (Boninger, Berent, and Krosnick Reference Boninger, Berent and Krosnick1995). Victims of IPV have personally experienced the emotional and physical impacts of victimization and tend to be more aware of services that exist for survivors (Kras Reference Kras2022)Footnote 4 and know what they need from their help-seeking process (e.g., Kulkarni, Bell, and Rhodes Reference Kulkarni, Bell and Rhodes2012). In addition, IPV survivors might have sought help from public services and relied on their own experience with procedural and distributive fairness to make that judgment. Conversely, they might have had no access to services, which also reveals information about government performance in coming to victims’ aid (Kras Reference Kras2022). In other words, IPV victims might be less uncertain about what to expect from existing government programs for victims.

I argue that IPV survivors are likely to have more negative evaluations of government performance in addressing GBV, given what we know about the lack of implementation of GBV laws and services in Latin America (e.g., Araújo and Gatto Reference Araújo and Malu2022; Neumann Reference Neumann2017). However, as individuals with strong attitudes toward public policy on GBV, victims should be less susceptible to information about other victims’ experiences with services. This discussion leads to the following hypotheses concerning respondents’ reactions to information about the way victims of GBV are treated by police in experimental vignettes:

H1: Information about the unfair treatment that an IPV survivor receives at a women’s police station will lower individuals’ evaluations of government performance in combating GBV.

H2: Actual IPV survivors will have more negative evaluations of government performance in combating GBV than nonvictims.

H3: Actual IPV survivors’ evaluations of the government’s performance in combating GBV will be less impacted by information about the unfair treatment an IPV victim received than other respondents.

Translating Attitudes into Behaviors

New information about poor interpersonal treatment that IPV survivors receive in specialized institutions should negatively influence individuals’ general evaluations of government performance in addressing GBV. But should such information also affect reported behaviors? I analyze this question using intentions of bystander intervention by contacting public institutions. Bystander interventions include ignoring the situation, preventing violence from escalating, or calling on outside resources for help (e.g., Bennett, Banyard, and Garnhart Reference Bennett, Banyard and Garnhart2014). Research has shown that in the Brazilian context, men are more likely to report willingness to intervene by calling the police if they witness a case of IPV when they live in a place with a local women’s police station (Córdova and Kras Reference Córdova and Kras2022). However, it is plausible that when people learn that IPV survivors receive unfair treatment from specialized institutions, they are less willing to call on these same institutions for help if they witness a case of IPV.

Scholars, however, have documented puzzling findings regarding people’s relationships with unresponsive institutions, revealing a disconnect between expressed attitudes and actions. Instead of avoiding those institutions, individuals might continue to reach out to them when needed, despite recognizing their ineffectiveness. Hilbink and colleagues (Reference Hilbink, Salas, Gallagher and Sanin2022) find that people in Chile and Colombia express overwhelmingly negative opinions of the justice system, but they still seek legal remedies when faced with rights violations. Similarly, Taylor (Reference Taylor2020) suggests that legal claim making in Colombia and South Africa is a function of the construction of the understanding of an issue as a right. Taylor (Reference Taylor2018) also suggests that people turn to institutions that they are profoundly skeptical of because they are understood to be the only mechanism through which citizens can access their rights. That is, the lack of alternatives, in light of the construction of understanding that citizens have a right to legal remedies, might compel individuals to return to institutions that they hold negative opinions about.

Informed by these findings, I argue that once people learn about a clear violation of the principle of fairness in an IPV survivor encounter with institutions for victims, they should be less likely to report intentions of calling upon that institution for help if they witness IPV, when presented with alternatives. When presented with other options for bystander intervention, people should be less willing to call upon help from an institution that violates victims’ dignity. That does not necessarily mean that individuals will perceive these institutions as illegitimate (e.g., Bell Reference Bell2017; Tankebe Reference Tankebe2009). However, procedural injustice might lead individuals to avoid contact with them, when presented with other options. That institution should no longer be their preferred point of contact when deciding how to intervene in a case of domestic violence (e.g., Bell Reference Bell2017).

H4: Information about the unfair treatment that an IPV survivor receives at a women’s police station will lower respondents’ willingness to call upon that institution for help if they witness IPV and instead prefer other alternatives.

The Brazilian Context

I test my hypotheses in the context of Brazil, where gender-based violence has remained a salient issue for decades (e.g., Santos Reference Santos2010). The process of political opening during re-democratization in the 1970s and 1980s overlapped with intense feminist mobilization around gender-based violence. The culture of impunity surrounding IPV was the main focal point of feminist activists at the time (Santos Reference Santos2010). The state responded to civil society’s demands with the creation of specialized public services for GBV victims, most notably with the creation of women’s police stations designed to respond exclusively to GBV (Santos Reference Santos2010). However, legal guarantees in the form of uniform federal legislation for victims of GBV, instead of a patchwork of disconnected public services, was only adopted in 2006.

The passage of the Maria da Penha Law in 2006, which addressed IPV specifically, was a paradigm shift in Brazil, placing GBV decisively in the political agenda and offering legal guarantees for victims while standardizing and connecting an array of public services for survivors (e.g., Santos Reference Santos2010). Since then, countless bills have been introduced in the national congress and local assemblies, and amendments have been passed to address loopholes and improve the implementation of GBV laws (e.g., Bigliardi, Antunes, and Wanderbrooke Reference Bigliardi, Antunes and Wanderbroocke2018). Among these centralized efforts to improve state response to GBV is the Law on Femicide of 2015 (Bigliardi, Antunes, and Wanderbrooke Reference Bigliardi, Antunes and Wanderbroocke2018). Despite these efforts, rates of GBV remain very high in Brazil, and implementation of laws has proved to be a major challenge (e.g., Araújo and Gatto Reference Araújo and Malu2022). Indeed, 8 out of the 13 presidential candidates in the first round of elections in 2018 had detailed plans to combat GBV (Hauber Reference Hauber2018), further illustrating the salience of the problem.

I test the effect of procedural fairness in victims’ encounters with specialized services on people’s perceptions of government effectiveness in responding to GBV using women’s police stations. Brazil was an early adopter of women’s police stations, and they are very well known among the public. For example, in a representative survey collected from Brazil in 2013, a staggering 96% of respondents reported awareness of the existence of women’s police stations. In the same survey, 48% of the participants selected the “women’s police station” option when asked which public services IPV victims should reach out to for help (Instituto Patricia Galvão 2013). Research has also demonstrated that women’s police stations significantly increase women’s trust in the police as an institution (Córdova and Kras Reference Córdova and Kras2020). Accordingly, these stations are undeniably the main public organization tasked with responding to GBV in Brazil (e.g., Santos Reference Santos2010). Given their salience as well as their effects on women’s attitudes toward the police and men’s attitudes toward GBV (Córdova and Kras Reference Córdova and Kras2022), they serve as a critical test to my theoretical expectations outlined earlier.

Data and Methods

To test my hypotheses, I use an original experiment embedded in a public opinion survey collected from a sample of Brazilian citizens in February 2021.Footnote 5 In all, 1,510 individuals were surveyed. The online survey was administered through NetQuest, which maintains a large respondent pool by offering tokens that can be traded for goods in exchange for occasional participation in surveys. Subjects from all 26 states and the federal district took part in the survey. NetQuest balances the sample on age, gender, social-economic status, and region of residency to meet those of the general population. Still, it is important to note that this sample does contain some small differences in the proportion of female and male respondents and the distribution across age groups when compared to the face-to-face survey collected by the Latin American Public Opinion Project in 2021. The distribution of respondents across regions in the NetQuest survey does match fairly well with the Brazilian census.Footnote 6 Research in public opinion comparing online surveys using samplings strategies similar to those used by NetQuest to nationally representative face-to-face surveys shows that results across samples are nearly indistinguishable (e.g., Clifford, Jewell, and Waggoner Reference Clifford, Jewell and Waggoner2015; Weinberg, Freese, and McElhattan Reference Weinberg, Freese and McElhattan2014).

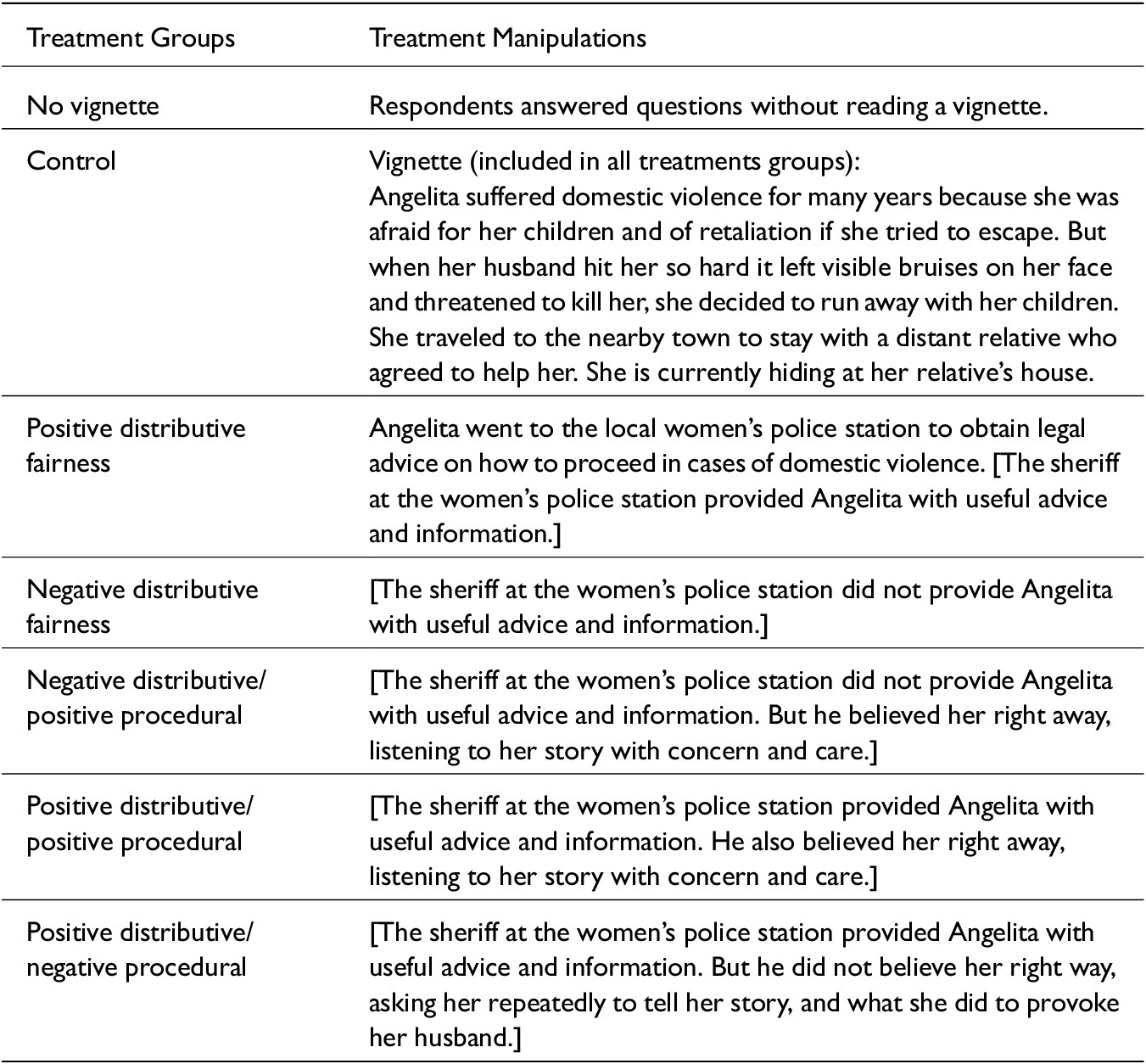

The present study employed a 2 × 3 design with one additional control group that did not receive a vignette (described in Table 1). Participants were randomly assigned to read vignettes about a case of IPV. All participants, except for the control group, were told about a victim of IPV who stayed in an abusive relationship because of her children. Participants were told that once the violence escalated, she decided to leave her husband and seek help at a women’s police station. At the station, she either received useful advice and information or did not receive advice and information (an outcome, i.e., distributive fairness). Importantly, the vignette told respondents what the victim was hoping to obtain by seeking assistance from the women’s police station. By explicitly telling respondents that she sought help from the women’s police station to obtain advice, the participant knew at least the outcome she was after. Scholars have operationalized distributive fairness in GBV research in terms of whether police involvement fits the victim’s preference for outcomes (e.g., Calton and Cattaneo Reference Calton and Cattaneo2014). The design of the vignettes used in this study was also animated by the extensive fieldwork that I conducted in Brazil. For example, in interviews with sheriffs from women’s police stations, I learned that IPV victims often seek their assistance to better understand their rights and options moving forward.Footnote 7

Table 1. Description of treatment manipulations

In addition, procedural fairness was manipulated by telling participants that the officer at the station either believed her right away and acted concerned, did not believe her right away and acted demeaning, or no information about the quality of interpersonal treatment was presented.Footnote 8 These manipulations were inspired by Tyler (Reference Tyler2000), who has argued that people are influenced by judgments about the honesty, impartiality, and objectivity of the authorities with whom they are dealing. When forming opinions about procedural fairness, people also judge whether the authority figure is benevolent and concerned about their situation (Tyler Reference Tyler2000). I argue that demonstrating concern is consistent with the expectation that authorities care about victims. In addition, in the context of GBV, authorities that listen to victims and refrain from questioning their role in the victimization (believing her), are more likely to be perceived as procedurally fair (e.g., Calton and Cattaneo Reference Calton and Cattaneo2014; Elliot, Thomas, and Ogloff Reference Elliot, Thomas and Ogloff2012).

This design allows me to assess the extent to which positive distributive fairness/negative distributive fairness, positive procedural fairness/negative procedural fairness/no information about procedural fairness, or a particular combination of the two, shapes people’s opinions about broader government efforts to combat GBV. I considered the theoretical argument as well as the number of observations per treatment condition in designing these categories. Therefore, the treatment categories do not include a negative distributive fairness/negative procedural fairness combination. As the focus of this study is whether negative procedural fairness is particularly damaging for opinions on GBV policies, an additional combined negative treatment would not enable me to distinguish between the two dimensions of fairness and would lower the number of observations per treatment (e.g., Clifford, Sheagley, and Piston Reference Clifford, Sheagley and Piston2021). Therefore, a positive distributive fairness/ negative procedural fairness condition is a critical test of the theory since survivors still received a positive outcome. Additionally, a positive distributive fairness/positive procedural fairness category is included as a check to my argument that negative treatments should be more powerful in predicting evaluations of GBV-related policies.

Similarly, informed by research findings on IPV victims’ re-utilization of services and distributive fairness (e.g., Hickman and Simpson Reference Hickman and Simpson2003), I include both a stand-alone positive distributive and a negative distributive fairness treatment condition. It is plausible that distributive fairness could be a strong consideration for bystander intervention attitudes. In all models, each treatment is included as a dummy variable, with the control group as a reference category.

Experimental designs can leverage causal inference while also considering other relevant individual-level and regional-level characteristics (e.g., Kam and Trussler Reference Kam and Trussler2017). In addition to the effect of procedural fairness on attitudes toward GBV policies, I include a dichotomous variable measuring IPV victimization by asking respondents whether they had experienced intimate partner violence in their lifetime (no is coded 0). In the sample, 247 respondents (16.3%) reported personal experience with IPV. To test H 3 , I include IPV victimization as a moderator in the models and its interaction with the procedural fairness treatment (see Kam and Trussler Reference Kam and Trussler2017). It is worth noting, however, that research in the context of postconflict societies in Africa suggests that the nondisclosure rate of self-reported sexual violence victimization in surveys is high (Koos and Traunmüller Reference Koos and Traunmüller2022). While the disclosure rate of IPV victimization in this study is similar to other nationally representative surveys collected from Brazil (e.g., Data Senado 2019), it is possible that IPV victimization is underreported in this survey. Nonetheless, the Brazilian government has engaged in notable efforts to promote awareness of the anti-GBV law for decades (e.g., Kras Reference Kras2022),Footnote 9 which might generate less stigma around disclosing IPV victimization in Brazil.Footnote 10

Additionally, given that individuals’ prior level of tolerance for GBV likely shapes attitudes toward GBV policies (e.g., Flood and Pease Reference Flood and Pease2009), the models also include a measure gauging tolerance of GBV. This question asked respondents how much they agreed with a popular Brazilian saying that illustrates high tolerance toward IPV (1 = low tolerance, 7 = high tolerance). I also include a measure of respondents’ sense of linked fate with women (1 = low linked fate, 7 = high linked fate). Research has found that linked fate shapes attitudes toward the criminal justice system (Hurwitz, Peffley, and Mondak Reference Hurwitz, Peffley and Mondak2015). Gender, age, and region of residency are also considered relevant characteristics and are included as controls in all models.

My theoretical argument is that information on procedural fairness should influence people’s attitudes toward government performance in combating GBV, the dependent variable in the analysis, asked after the experimental vignette. I tapped two different aspects of the government’s performance in the area of GBV with questions asking respondents whether they agree on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with the following statements: (1) “Women who suffer domestic violence can count on the support from the government” (mean = 3.3, SD = 1.9) and (2) “Brazilian laws protect women from domestic violence” (mean = 3.6, SD = 1.9). Twenty-five percent of respondents strongly disagreed with the first statement and 20% strongly disagreed with the second statement.

To test the effect of procedural fairness on bystander intervention ( H 4 ), after answering the two questions on the government’s effectiveness in addressing GBV, respondents were asked to consider a scenario in which they witnessed a case of domestic violence. On a 4-point scale, they were then asked to assess the probability, from 1 (low probability) to 4 (high probability), of calling or contacting the following: women’s police station, regular police station, the church, friends and family, crisis center, NGO, and doing nothing as this is a private matter. Importantly, this question presented respondents with clear alternatives to contacting a women’s police station. Strikingly, 63% of respondents indicated they would call for help from a women’s police station—further illustrating their salience in Brazil.

Results

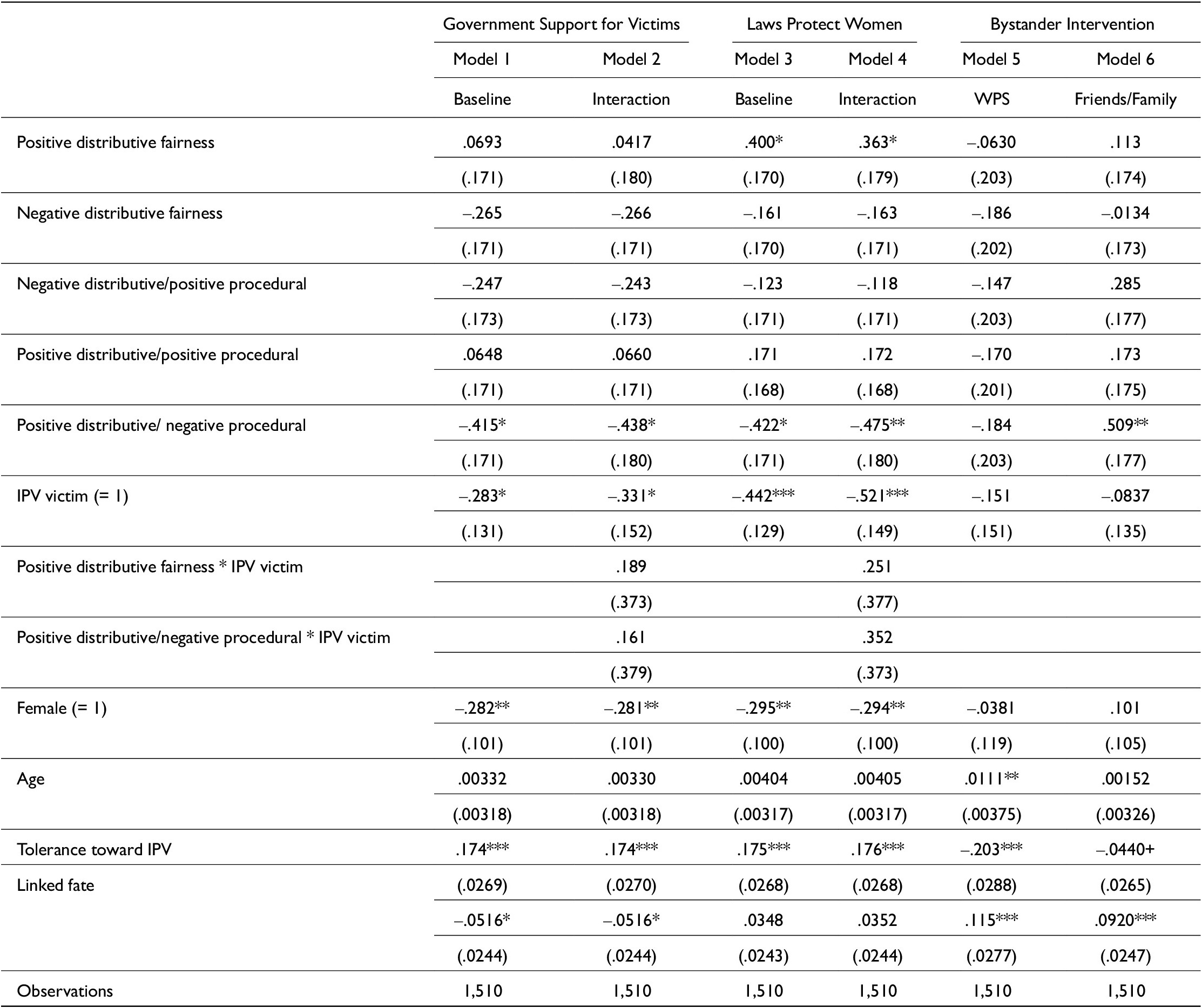

Table 2 presents the results of a series of ordered logit models that test H 1 through H 4 . The dependent variable in Models 1 and 2 is participants’ opinions about the government’s job in coming to IPV victims’ aid (government supports), while the dependent variable in Models 3 and 4 is opinions about the performance of GBV laws (laws protect). The dependent variable in Models 5 and 6 is participants’ bystander attitudes, with Model 5 testing the likelihood of calling upon help from a women’s police station (WPS) and Model 6 testing the likelihood of contacting informal networks of friends and family.

Table 2. Effects of procedural fairness on opinions about the state’s action on GBV

Notes: Ordered logit. The control group is the reference category in all models. The no-vignette category and regional fixed effects were included but omitted from the table. The complete table is presented in the appendix (Table A3). Standard errors in parentheses. *** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05; + p < .10.

The baseline models (Models 1 and 3) indicate that, on average, the positive distributive/negative procedural fairness treatment lowers respondents’ confidence in the government’s support for victims (p < .05) and evaluations of GBV laws (p < .05), providing support for H 1 . This is the only treatment that exerts significant negative effects on both dimensions of state efforts to combat GBV. The presence of both procedural and distributive fairness (positive distributive/positive procedural) did little to improve evaluations of the state’s performance in responding to GBV compared to the control condition. This is consistent with research that has found that negative information can be more consequential in shaping attitudes than positive information (e.g., Mondak et al. Reference Mondak, Hurwitz, Peffley and Testa2017). In this way, the present study is consistent with others in suggesting that unjust events exert stronger effects on people’s cognitions and reactions than just events (e.g., Van den Bos et al. Reference Van den Bos, Maas, Waldring and Semin2003).

Models 1 and 3 indicate that information about negative procedural fairness can offset the positive effects of information about distributive fairness on broader evaluations of government performance in addressing GBV (positive distributive/negative procedural). These results suggest that negative process-based information about service provision for victims at the local level can be used by citizens to form evaluations of government performance in that policy area. In this case, information about a procedurally unfair event at the WPS generated negative attitudes among respondents that metastasized across their performance evaluations of GBV laws and the quality of government assistance to victims. Crucially, this particular vignette allowed me to assess the impact of information about an unfair process (disrespect) occurring in conjunction with a fair distributive outcome (victim receiving useful advice and information). The results are consistent with works that have found that clear violations of principles of fairness of procedures matter more than the delivery of desired outcomes (distributive fairness) (e.g., Doherty and Wolak Reference Doherty and Wolak2012), especially in cases involving considerable uncertainty (e.g., Lind and Van den Bos Reference Lind and Van den Bos2002).

Interestingly, the treatment condition for positive distributive/no information about procedural fairness significantly increases agreement with the laws protect item but not the government supports item. One can speculate that when victims receive a favorable outcome, respondents view it as an indication that the laws are indeed being implemented, but it says nothing about political actors and their commitment to supporting victims. However, a stronger distributive fairness treatment condition, such as the attainment of a restraining order, might prime more safety considerations than advice or information, which could improve views along the two dimensions substantially. Future research is necessary to test the validity of this argument.

Focusing on IPV victimization, Models 1–4 show that IPV victims have significantly more cynical attitudes toward the government supports and laws protect items, compared to nonvictims, supporting H 2 . Doubtless, survivors are more aware of the dismal level of implementation of GBV laws in Brazil—with women’s police stations and IPV shelters established in only about 8.3% and 2.4% of municipalities, respectively (Araújo and Gatto Reference Araújo and Malu2022). Their own experience likely revealed more information about these state efforts than what is accessible to nonvictims. These results correspond with research on crime victimization, which consistently finds that crime victims have lower trust in the criminal justice system (e.g., Blanco and Ruiz Reference Blanco and Ruiz2013).

Models 2 and 4 test whether the effect of violations of procedural fairness on attitudes are moderated by victimization ( H 3 ). Contrary to my expectations, I find no evidence that IPV victims are less susceptible to information on violations of procedural fairness than nonvictims. As such, these results suggest that survivors might not have crystalized attitudes toward state efforts to combat GBV. It is possible that most survivors in this sample have not had direct experiences with women’s police stations and other services for survivors, which might generate some uncertainty. Thus, while survivors have lower baseline confidence in state efforts in addressing GBV, they are still influenced by other victims’ negative experiences. Crucially, “IPV victims” are not a homogenous group (e.g., Kras Reference Kras2022). Perhaps it is having prior experience with both IPV victimization and specialized services that generates stronger attitudes toward the state’s performance in responding to GBV. In addition, it is also plausible that those who have been exposed to victims’ experiences through familial or social networks in general, regardless of victimization status, have more crystalized attitudes toward policies on GBV. To investigate these possibilities, further inquiry is needed.

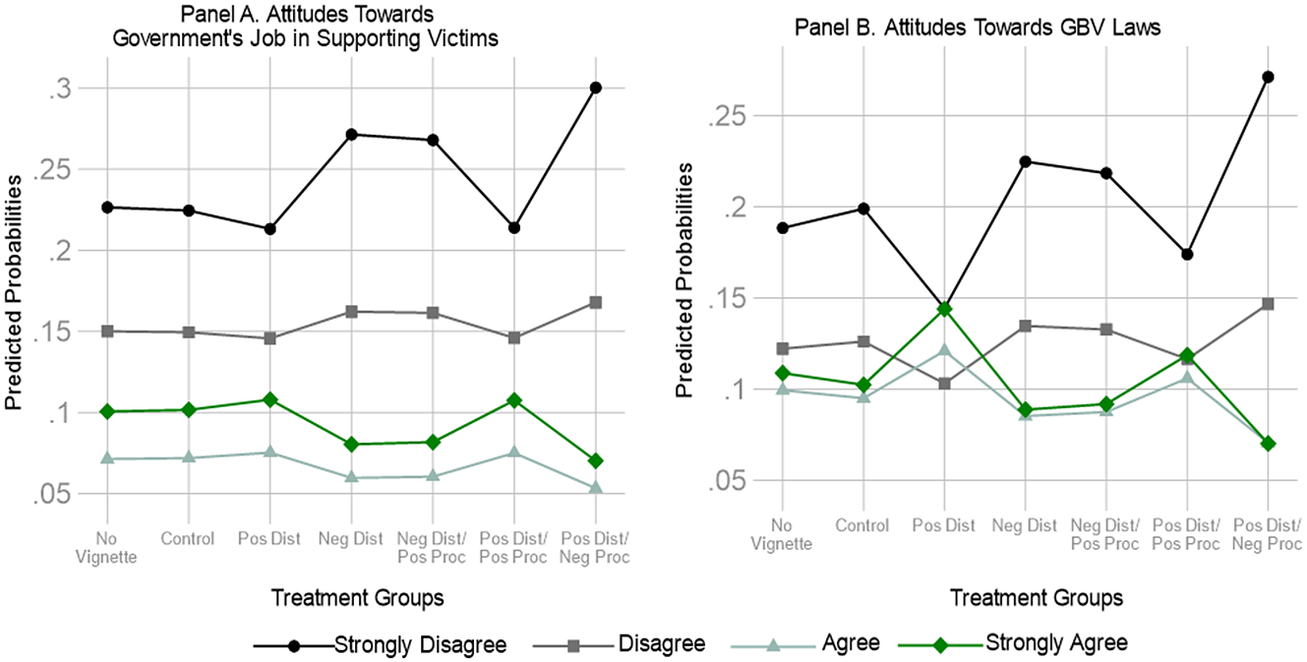

Figure 1 presents the predicted probabilities for agreement and disagreement with government supports and laws protect across all experimental conditions. The graph illustrates the substantive effects, further demonstrating how negative procedural fairness is uniquely damaging for evaluations of the state’s performance in addressing GBV. As can be observed, the average predicted probability of those in the positive distributive/negative procedural treatment of completely agreeing with the government supports item is abysmally small at 7% (Panel A). In sharp contrast, the probability of completely disagreeing with the statement is 30 %. This is a statistically significant difference of 8 percentage points compared to the control. Moreover, the average predicted probability of those in the positive distributive/negative procedural treatment of completely agreeing with the laws protect item is 7% (Panel B), while the probability of completely disagreeing with the statement is 27%. These results offer support for H 1 .

Figure 1. Predicted probability of agreeing or disagreeing with government supports and laws protect items across conditions. Panel A is based on Model 1 and Panel B is based on Model 3, Table 2. Treatment groups are as follows (from left to right): positive distributive fairness, negative distributive fairness, negative distributive/positive procedural, positive distributive/positive procedural, and positive distributive/ negative procedural. Figures A5 and A6 of the appendix present results for all options in the Likert-scale (1–7) across all treatment groups.

In addition to the findings directly testing my theoretical expectations, the impact of several demographic and attitudinal controls in Table 2 is noteworthy. Women, for example, are much less likely than men to think that the government supports and laws protect women from abuse, undoubtedly because women are more likely than men to recognize that women suffer discrimination and abuse in society (e.g., Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019). Moreover, two attitudinal measures—tolerance toward IPV and linked fate—significantly affect all three dependent variables in Table 2. Those who are more accepting of IPV hold more positive evaluations of state efforts to combat GBV. Importantly, being more tolerant of IPV is associated with a greater reluctance to report an incident of IPV to a WPS (p < .001). As expected, perceived linked fate with women engenders more pessimistic views of the government’s support for IPV victims but also compels people to call upon help from WPS and friends/family if they know of a domestic violence case. These results indicate that policies that shape social norms can be powerful in influencing an array of attitudes and behaviors related to GBV.

Predicting Bystander Interventions

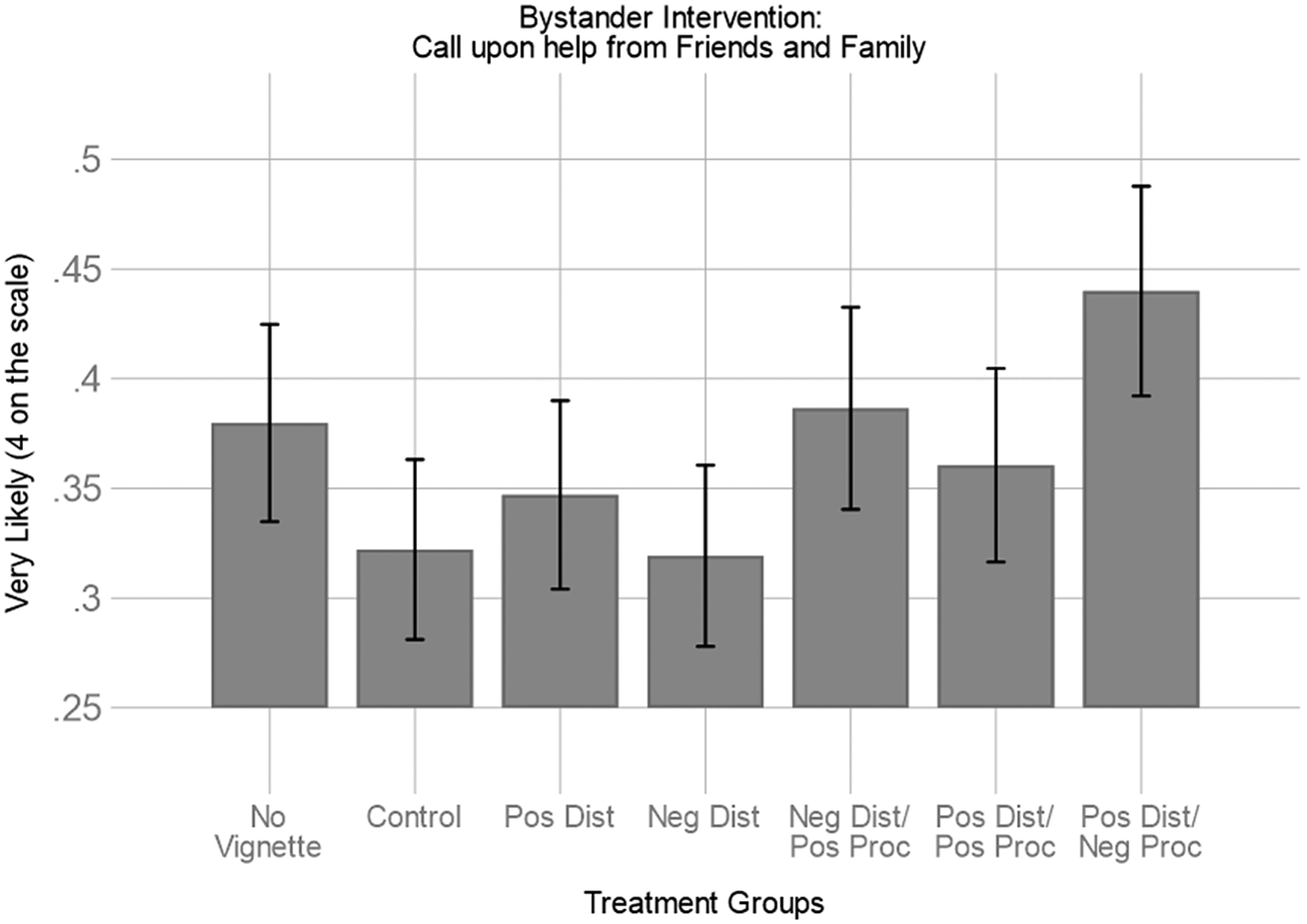

My last hypothesis, H 4 , predicts that when presented with clear alternatives to public institutions, individuals will avoid contact with services that violate principles of fair process. Models 5 and 6 in Table 2 test respondents’ likelihood of calling law enforcement agents who specialize in dealing with GBV (WPS) or turning to a private source for help (friends and/or family). Surprisingly, the results show that none of the treatment conditions significantly influenced respondents’ willingness to call WPS for help after witnessing domestic violence. These findings are consistent with research conducted in the context of Latin America that finds people might continue to reach out to institutions despite recognizing their ineffectiveness. (e.g., Hilbink et al. Reference Hilbink, Salas, Gallagher and Sanin2022; Taylor Reference Taylor2018). However, the novelty of these results is that the question presented respondents with clear alternatives to contacting WPS, yet it did not lead to avoidance of WPS.

There are many possible explanations for this nonfinding. For years, the Brazilian government has engaged in notable efforts to spread awareness about reporting IPV to the police. More than a decade of awareness campaigns emphasizing reporting IPV to the WPS presumably cemented the idea that reporting is the right course of action (see, e.g., Taylor Reference Taylor2020). It is likely that when confronted with the question of what one would do in those situations, reporting IPV to a WPS is the information heuristic most readily available to people. Against this backdrop, it is also possible that social desirability bias could explain people’s self-reported intentions of calling a WPS. More research is needed to test these possibilities.

Crucially, the IPV victim that experienced an unfair procedure in the vignette still received a desired outcome: useful advice and information (positive distributive/negative procedural). It is plausible that distributive fairness might be a stronger consideration when it comes to people’s bystander intervention (an action involving high consequences). These findings are in contrast to those reported by Henry, Franklin, and Franklin (Reference Henry, Franklin and Franklin2020). Their research finds that survey participants who view the police as procedurally fair are more likely to report intentions of referring sexual assault survivors to the police. But my findings are consistent with Hickman and Simpson (Reference Hickman and Simpson2003), who do not find a link between IPV survivors’ intentions of re-utilizing police services and procedural fairness. It is entirely possible that these inconsistent conclusions result from the source of procedural fairness, as these two papers analyzed personal experience with procedural fairness while the present study analyzed vicarious exposure through vignettes. While the evidence presented in this article joins others in suggesting that vicarious experience with procedural unfairness influences citizens’ evaluations of the justice system (Mondak et al. Reference Mondak, Hurwitz, Peffley and Testa2017), this discussion reveals the need for more research testing the link between vicarious experience and behaviors.

Results in Model 6, however, demonstrate that those in the positive distributive/negative procedural treatment were significantly more likely to say they would call friends and family if they witnessed a domestic violence case (p < .01). Figure 2 illustrates the predicted probability of calling friends and family for each of the scenarios. If the victim is subjected to unfair (process) treatment by the police (positive distributive/negative procedural), respondents are 44% likely to call friends and family, which is a 12-point increase compared to the control. Clearly, when the police demean the victim by subjecting them to unfair procedural treatment, people are much more open to nongovernmental private remedial help. In addition, respondents confronted with the procedurally unfair treatment were significantly more likely to select the option of “doing nothing, because this is a private matter,” albeit the results were small (see Table A5 and Figure A7 in the appendix). Aside from these two outside options, the respondent’s willingness to call other agents (regular police station, the church, crisis center, or NGO) was not significantly influenced by the scenario treatments. The results in Table 2 and Figure 2 offer partial support for H 4 . Violations of procedural fairness can compel people to turn to informal, noninstitutional channels and other forms of self-help—as has been demonstrated by research in other domains (e.g., Gau and Brunson Reference Gau and Brunson2015; Nivette Reference Nivette2016). The findings demonstrate that despite years of messaging by the Brazilian government to encourage bystanders to report IPV to WPS, victims’ experience with procedural injustice seems to make Brazilians open to nonformal alternatives (e.g., family/friends).

Figure 2. Based on Model 6, Table 2. Predicted probabilities, 87% CIs.

Additional Tests: Mediation Analysis

In this section, I examine whether the effects described earlier are indeed driven by perceptions of procedural fairness. That is, I test whether the effect of the treatment was mediated by two measures of procedural fairness.Footnote 11 Following Sunshine and Tyler (Reference Sunshine and Tyler2003), I assess the mediating effect of respondents’ agreement with this statement: “The police treat people with dignity and respect.” Similarly, I test whether agreement with the statement “Women are victimized again when reporting IPV” also mediates these effects. Victims of GBV are at risk of developing a myriad of psychological and emotional problems and poor interpersonal treatment from providers can compound these symptoms (e.g., Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Sefl, Barnes, Ahrens, Wasco and Zaragoza-Diesfeld1999). This statement captures whether respondents interpret poor interpersonal treatment as harmful to survivors’ well-being. To test these mediation effects, I estimate structural equation models to calculate the effects of each of these procedural justice variables assumed to mediate the effects of negative procedural treatment by the police on government action on GBV (Figure 3, Panel A) and bystander intervention (Panel B), while accounting for control variables in the models (e.g., Hayes Reference Hayes2018).

Figure 3. Results of mediation analysis. Dashed arrows represent statistically significant paths. Full results are reported in Table A6 in the appendix. Control variables are included in the models.

Figure 3 summarizes the results of the mediation analysis. The dashed and solid arrows represent the statistically significant and nonsignificant paths, respectively. Consistent with the procedural fairness thesis, Panel A shows that the positive distributive/negative procedural treatment group is much less likely to agree with the statement “The police treat people with dignity and respect” (a measure of procedural fairness) (p < .01). Procedural unfairness, in turn, lowers respondents’ evaluations of state efforts to address GBVFootnote 12 (p < .001). Thus, while the direct link between the treatment group and these evaluations is also significant (p < .05), procedural fairness strongly mediates these effects. Likewise, we also observe a similar pattern for bystander intentions of contacting informal channels of friends and family, with direct and indirect effects of the treatment group. And while respondents in the positive distributive/negative procedural treatment are more likely to believe that women are victimized again when seeking formal help (p < .001), this mediator is not a significant predictor of attitudes toward government efforts to address GBV or bystander attitudes. In brief, learning about IPV survivors’ experience with services such as women’s police stations can have a negative spillover effect on broader evaluations of government performance in dealing with GBV through perceptions of procedural injustice.Footnote 13

Further analyses, presented in Table A7 and Figures A9–A10 in the appendix, provide additional support to the effects uncovered in the mediation analysis. Based on a series of ordered logit models using those mediating variables as dependent variables, we can observe that the positive distributive/negative procedural treatment is the only category that exerts effects on views about the police treating people with respect. Respondents in the procedural injustice treatment were 35% likely to completely disagree with the statement “The police treat people with dignity and respect” (p < .05). The control groups, meanwhile, were 26% (no vignette) and 28% (control) likely to select that category. This provides further evidence that the effects uncovered in the main analysis presented earlier are indeed operating through views of procedural justice.

Table A7 in the appendix also presents the results of models testing the effect of each treatment and control categories on views of secondary victimization. The positive distributive/negative procedural treatment had no effect on perceptions of secondary victimization compared to the control group. Indeed, the control group displayed some of the most negative views on this statement. However, the positive distributive/negative procedural treatment had a statistically significant effect on views of secondary victimization when compared to the group who answered questions without reading a vignette (p < .001). Respondents in the positive distributive/negative procedural treatment were 38% more likely to completely agree with the statement “Women are victimized again when pressing charges against IPV.” In contrast, respondents in the no-vignette group were 24% more likely to completely agree with this statement. Indeed, poor interpersonal treatment of survivors of IPV in public institutions clearly violates principles of fairness that people care about deeply.

Conclusion

Gender-based violence is a persistent and destructive practice around the world with implications for women, children, and society at large. In order to curtail rates of GBV, the United Nations recommends a combination of long-term strategies aiming at addressing social norms that normalize GBV and short-term measures to respond to violence (UNODC 2020). These goals can be accomplished by strengthening victims’ access to specialized services and by intervening in specific situations that can trigger lethal violence (UNODC 2020). GBV services, however, require public investment, making them subject to political contestation (e.g., Araújo and Gatto Reference Araújo and Malu2022). Therefore, it is imperative for us to understand the attitudes of people who have not experienced GBV firsthand toward these policies and GBV in general. Nonvictims make up most of the public, and their opinions might be the most crucial for the continued funding and expansion of services for victims.

In this article, I sought to examine the process of attitude formation on evaluations of state efforts to combat GBV. While studies have found that establishing services for survivors can generate attitudes more critical of GBV (e.g., Córdova and Kras Reference Córdova and Kras2022), we know little about individuals’ opinions once they receive more information about how services operate in practice. I theorized that as a policy domain about which most people have incomplete information, evidence of procedural fairness should be a relevant consideration for people when judging the effectiveness of state actions on GBV. Indeed, using survey experiments, I find that when survivors receive poor interpersonal treatment at a women’s police station—procedural unfairness—respondents were significantly more critical of the effectiveness of GBV laws in protecting victims and of the government in aiding women in situations of violence. Further mediating analysis confirms that these treatment effects were driven by perceptions of procedural unfairness.

This article also finds that information on procedural unfairness in a victim’s encounter with specialized police shapes reported bystander intervention attitudes. I find that while people in the procedural unfairness treatment still reported intentions to contact a women’s police station if they witnessed a case of IPV, they were more likely to consider outside options. They were much more likely than other categories to report intentions of contacting friends and family if they were in such situations, suggesting that they were more open to options outside the state and other specialized institutions. These results are consistent with research on crime that finds that procedural unfairness compels people to adopt more self-help attitudes (e.g., Gau and Brunson Reference Gau and Brunson2015; Nivette Reference Nivette2016). As much as one-third of reported IPV incidents in the United States are witnessed by a third party, such as a neighbor or friend (e.g., Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Banyard, Grych and Hamby2019). While questions remain about the role of bystanders in cases of IPV, reactions from victims’ informal networks can be decisive in victims’ decisions to seek formal help (e.g., Medie Reference Medie2017). Thus, the course of action taken by a bystander can have massive consequences for all involved.

Taken together, the findings of the present study add to our understanding of the role of information about victims’ experiences with specialized services on people’s attitudes and reported behaviors. Its findings join others in demonstrating the importance of procedural fairness for the formation of attitudes. Importantly, this analysis suggests that information on procedural unfairness can offset the positive effects that the existence of services might have on attitudes and bystander intervention (e.g., Córdova and Kras Reference Córdova and Kras2022). This might have implications for the funding of such programs.

It is important to note the limitations of this study. First, the sample was restricted to Brazilian citizens, which is arguably a unique country case in the realm of GBV. As noted throughout the article, Brazil has established visible institutions for victims at the local level. As a result, it is entirely possible that the nature of the processes under investigation would be different in other contexts. Nonetheless, based on the theoretical framework outlined in the present study, I would expect procedural fairness to matter even more in contexts where services for victims have been established more recently or are less known. Second, grounded in previous works, I have suggested that the mechanisms underpinning the results might be the respondents’ emotional reactions to the treatments. These mechanisms, however, were not directly tested in this study. And finally, the treatment manipulations of distributive fairness in this study employed only one outcome (information and advice). It is possible that different operationalizations of distributive fairness would reveal different effects. I suspect that information about a victim receiving a restraining order as an outcome could be particularly useful for respondents in deciding how they would act if they witnessed violence. As such, expanding this research to other contexts, directly testing proposed underlying mechanisms, and employing different configurations of distributive fairness are fruitful paths forward in this research agenda. Future research should also investigate the link between critical attitudes and support for funding specialized services for victims of GBV and alternative ways to measure IPV victimization (e.g., Koos and Traunmüller Reference Koos and Traunmüller2022).

Moreover, research testing the theoretical arguments outlined in this paper beyond policies around gender is certainly in order. Besides anti-GBV policies, I would also expect my argument to apply to policy areas where citizens have incomplete information, uncertainty, and limited direct experience. For example, environmental policy is an area with high levels of uncertainty, especially around the exact impacts of climate change and the appropriate ways to remedy them (e.g., Spencea, Poortingab, and Pidgeon Reference Spencea, Poortingab and Pidgeon2012). Therefore, I would expect procedural fairness to be an important consideration for people when evaluating various attempts to curtail climate change, such as clean energy. Further, information on procedural fairness could be relevant for people in their assessments of welfare institutions. Most people have had no direct experience with poverty alleviation programs (see Soss Reference Soss1999 for a discussion of welfare recipients). In short, information about procedural fairness in policy areas with these characteristics might have implications for citizens’ support for continued funding and expansion of these efforts as well as their perceptions of the need for the policy. Such studies would also reveal important considerations for policy design and implementation. However, I do not believe that procedural fairness matters in every policy area. When people have strong policy preferences, or if there is polarization around a topic, then research suggests that procedural fairness might be used instrumentally, or disregarded altogether (e.g., Esaiasson et al. Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2016). In addition, if the outcome of a policy is unmistakably life-saving or life-threatening, it is rather reasonable to expect that information on distributive fairness would trump procedural fairness in people’s evaluations, regardless of the level of uncertainty. I would be curious to see more research that would test such insights.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X23000351.

Acknowledgments

This research received financial support for data collection from the American Political Science Association’s Diversity Fellowship Program. I would like to thank Mark Peffley and Rachel Vanderhill for their extensive feedback and comments on earlier drafts of the survey and manuscript. I also received valuable comments from participants at the Midwest Political Science Association conference. Finally, I would like to extend my gratitude to three anonymous reviewers and the editor for their excellent feedback and suggestions on earlier versions of this article.

Competing interest

The author declares none.