INTRODUCTION

In 1988, Karen Kantzler, a 36-year-old woman living in West Bloomfield township of Oakland County, Michigan, was arrested for killing her husband, Dr. Paul Kantzler. The Kantzlers had been married for about five years at the time of the murder. During the trial, evidence of systematic abuse of Ms. Kantzler by her husband emerged. Ms. Kantzler alleged that her husband had beaten her since the start of her marriage, and that the abuse was both physical and emotional. She was not allowed to drive or to open her own bank accounts. Dr. Kantzler, in fits of drunken rage, would often threaten to kill her. Her doctors testified that she often had bruises. Ms. Kantzler had considered divorce and had even consulted a divorce lawyer on the advice of the Women's Counseling Center in Detroit. But the lawyer was too expensive, and Ms. Kantzler was unsure how she would support herself financially. Things came to a head on the night of March 11, 1987, when police responded to a call from the Kantzler residence to find Dr. Kantzler dead with a gunshot wound to the left side of his head. Although Ms. Kantzler initially tried to suggest that this was a suicide, she soon confessed to having killed Dr. Kantzler in self-defense. She alleged that she and Dr. Kantzler had been having an argument. He had gone up to bed first and, a little later, had summoned her to the bedroom; she went up and saw him standing holding a gun. He kicked her and threw her against the wall, screaming that she had ruined his life and that he should kill her so that he could start over. Ms. Kantzler fought back and in the ensuing struggle, the gun went off and Dr. Kantzler was killed.

How do the courts handle cases like Karen Kantzler's? That is, how do they treat a woman accused of a violent crime against an alleged abuser? Do they treat her more leniently because she claimed to have been protecting herself? Or do they punish her more severely because of her transgressions against ascribed gender roles?Footnote 1 In this article, I offer one answer to these questions based on analysis of an original data set of homicide cases in Oakland County, Michigan, over the three-year period of 1986 to 1988. My results are startling: I find that female defendants were convicted more frequently than were male defendants; there is an interactive effect with race; and the conviction rate was higher if the victim was an alleged batterer of the defendant. My data indicate that sentencing decisions have a clear racial aspect to them.

The article is organized as follows. In the next section, I build on the sexual stratification hypothesis to develop a theoretical framework to understand how gender and race intersect in society's treatment of women accused of violent crimes against alleged abusers. I contrast this framework against existing arguments about paternalism in the relevant research on gender effects in the justice system.Footnote 2 I then turn to homicide data from Oakland County, Michigan, to test propositions implied by my argument. I conclude with a summary of findings and a consideration of the implications of my research for future research by political scientists interested in issues of politics and gender.

SEX AND THE COURTS

Sexual violence—or, more precisely, society's reaction to it—has received considerable attention by scholars of gender and politics because of what it tells us about how women and men are valued, allowing investigators to understand better mechanisms of social control in the preservation of hierarchy and status (Carraway Reference Carraway1991; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Davis Reference Davis1985; LaFree Reference LaFree1980; Weldon Reference Weldon2002, Reference Weldon2006a, Reference Weldon2006b). The dominant understandings of sexual violence focus on the incidence of rape and, increasingly, of domestic violence. Compared with the former, however, the latter is a relatively recent focus of inquiry, even though women are far more likely to be victimized by an intimate partner than by a stranger. Even less well understood, as a result, is how society treats those who respond to threats and use of sexual violence against them with violence of their own. Yet this question, of how society categorizes and treats victims of domestic violence who respond to their attackers with force, is theoretically important because it helps distinguish between existing arguments about the origins and purpose of the law, as well as how legal institutions are gendered (and, indeed, to use Mary Hawkesworth's phrase, “raced-gendered”).

In this section, I develop a theoretical argument to tackle this question by building on the “sexual stratification hypothesis” (Collins Reference Collins1975; LaFree Reference LaFree1980; Walsh Reference Walsh1987). Briefly, the sexual stratification hypothesis posits the following propositions:

1. Women are viewed as the valued and scarce property of the men of their own race.

2. White women, by virtue of membership in the dominant race, are more valuable than black women.

3. The sexual assault of a white by a black threatens both the white man's “property rights” and his dominant social position. This dual threat accounts for the strength of the taboo attached to interracial sexual assault.

4. A sexual assault by a male of any race upon members of the less valued black race is perceived as nonthreatening to the status quo, and therefore less serious.

5. White men predominate as agents of social control. Therefore, they have the power to sanction differentially according to the perceived threat to their favored social position. (Walsh Reference Walsh1987, 155)

The sexual stratification hypothesis thus explains the law as a system of social control developed by the dominant group in society (here, white men) to preserve their position at the apex of two distinct but intersecting hierarchies: sexual and racial. In this system of “intersecting hierarchies,” women occupy an inferior position to men, and black women are the least valuable, below white men and women on account of their race and below black men on account of their sex (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; see also Black Reference Black1983).

The sexual stratification hypothesis, with its explicit incorporation of a perspective of “intersectionality,” is a useful analytical tool for understanding how American society treats those who perpetrate sexual violence. But what can it tell us about how society treats those who push back and attack those who have previously attacked them?

By the logic just described, murders by victims of domestic violence (MVDA) are particularly interesting since they are potentially threatening to both sexual and racial hierarchies. If women are considered the “property” of men, then domestic violence can be understood as a right of men over the women with whom they live. Indeed, the embarrassingly poor record of most societies in responding aggressively to domestic violence in the absence of strong women's movements domestically is well explained in this light (Weldon Reference Weldon2002, Reference Weldon2006a). Therefore, a woman who attacks her alleged batterer violates not just traditional gender roles of passivity and caregiving but also a sexual hierarchy that grants men power over her. As such, from this perspective, ceteris paribus, we should expect murders of male batterers by female victims of domestic violence to be treated more seriously by the legal system, which reflects the preferences of the dominant social group in society.Footnote 3

Second, as argued, white and black women occupy different rungs in the social hierarchy. White women are generally considered more valuable in this society and are accorded a different set of values and roles than are black women. Where white women have been regarded as “gentle creatures” requiring protection, black women have been stereotyped as lazy, promiscuous, and irresponsible (Hancock Reference Hancock2004). Both sets of stereotypes are correctly understood as methods of social control in the service of white male patriarchy as they consign both groups of women to tightly proscribed roles in society and limit their members' opportunities for advancement in society. But the implications for white and black women facing the legal system are consequently different. While white women who “protect themselves” from violent attackers might be shown leniency by the courts, black women are more likely to be blamed for getting into such a situation and for “bringing it on themselves.” Accordingly, a second expectation that arises is that white women who kill their batterers should be treated less severely than black women in the same situation.

Finally, a third testable implication follows from the preceding set of arguments. Specifically, the essence of intersectionality suggests that the treatment of interracial cases of female intimate partner homicide should vary depending on the race of the woman in question. The sexual stratification hypothesis argues that relations between black men and white women violate the dominant group's power most directly. Therefore, abuse of white women by black men is considered particularly heinous in this society and treated more harshly (Williams and Holcomb Reference Williams and Holcomb2004; but see Stauffer et al. Reference Stauffer, Smith, Cochran, Fogel and Bjerregaard2006). White women who retaliate against a black male batterer should be viewed most worthy of “protection” by society at large, and therefore treated least severely by the courts. In sharp contrast, the double power of white men over black women places the latter in an especially vulnerable position, without resort to public sympathy. We should anticipate that black women who kill white male batterers will be treated most harshly by the courts.

The argument developed in this section thus makes three contributions theoretically. First, it extends the sexual stratification hypothesis to help us understand societal reactions to women who retaliate against those who use sexual violence against them. Second, the explicit incorporation of an intersectionality perspective allows me to generate additional observable implications of the sexual stratification hypothesis pertaining to the differential treatment of white and black women who kill their batterers. Finally, the literature on intersectionality can trace its origins to the study of sexual assaults against women (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Davis Reference Davis1985; Weldon Reference Weldon2006b). Accordingly, this study, by focusing instead on the use of violence by women in response to domestic violence, completes the circle and deepens our understanding of the dynamics of intersectionality.

Existing Research: Judicial Paternalism

The aforementioned argument is easily contrasted with the dominant paradigm in the criminology literature, typically labeled the “paternalism” or “chivalry” hypothesis (Gruhl, Welch, and Spohn Reference Gruhl, Welch and Spohn1984; Spohn Reference Spohn1999; Spohn and Beichner Reference Spohn and Beichner2000; Spohn, Welch, and Gruhl Reference Spohn, Welch and Gruhl1985).Footnote 4 This hypothesis states that women are treated more leniently by a predominantly male judiciary because they are seen as less culpable and are considered less likely to be recidivists and more in need of protection. According to this perspective, male judges in particular are less likely to view female dependents as posing a threat to the community and to weigh their roles as caregivers more heavily in their sentencing decisions. Interviews of judges in Massaschusetts by Kathleen Daly in Reference Daly1989 revealed that judges worried about the social costs of imprisoning women since they expected that women were likely responsible for caring for any dependants in the family (Daly Reference Daly1989).Footnote 5

The existing empirical research appears to support this perspective. Given that women are less likely than men to commit crimes, and especially violent crimes, existing research interested in how courts “see gender” typically focuses on the role of victim gender, although more recent research has begun to examine offender gender as well. The dominant expectation in the literature has been that defendants accused of killing women are more likely to be convicted and are less likely to receive a reduced charge from the prosecution (Baumer, Messner, and Felson Reference Baumer, Messner and Felson2000; Beaulieu and Messner Reference Beaulieu and Messner1999; Curry, Lee, and Rodriguez Reference Curry, Lee and Rodriguez2004, 321; Glaeser and Sacerdote Reference Glaeser and Sacerdote2000).

By comparison, research on sentencing outcomes has been more conflicted. Martha Myers (Reference Myers1979) studies a sample of felony offenders in Marion County, Indiana, from 1974 to 1976 but finds no effect of victim gender on the sentencing decision. Cassia Spohn's (Reference Spohn, Bridges and Myers1994) study of violent felony offenders in Detroit from 1976 to 1978 also reveals no evidence of any victim-gender effect in sentencing. Edward Glaeser and Bruce Sacerdote (Reference Glaeser and Sacerdote2000), however, utilize a much larger data set than either Myers or Spohn and find evidence for an interactive effect between victim gender and offender gender. Men convicted of victimizing a woman were punished more severely than any other victim gender/offender gender combination. Most recently, Theodore Curry et al. confirm this interactive hypothesis in a sample of Texas felony cases, finding that “the longest sentences are meted out to male offenders who victimize females, and [that] this difference is considerable, with the female victim/male offender dyad receiving sentences that range from 4.348 to 10.385 years longer than the other victim gender/offender gender dyads.”Footnote 6 Marian Williams and Jefferson Holcomb (Reference Williams and Holcomb2004) expand on this finding by exploring the intersection of race and gender of the victim. They find that homicide cases in Ohio that had white female victims were most likely to result in death penalty sentences for the defendant. Most recently, Amy Stauffer et al. (Reference Stauffer, Smith, Cochran, Fogel and Bjerregaard2006) replicated the Williams and Holcomb study using data from North Carolina, and found that while bivariate analysis suggests the existence of a white female victim effect, the introduction of control variables eliminates any gender or race effects in sentencing.

A second strand of this research program investigates the effect of offender gender on judicial outcomes. Here, the findings have been more consistent than is the case for victim gender: Female defendants receive more lenient sentences than do men and are less likely to be incarcerated than are men (Daly Reference Daly1989; Daly and Bordt Reference Daly and Bordt1995; Daly and Tonry Reference Daly, Tonry and Tonry1997; Spohn and Beichner Reference Spohn and Beichner2000). Cassia Spohn and Dawn Beichner (Reference Glaeser and Sacerdote2000) conducted a comprehensive analysis of more than seven thousand felony cases from 1993 across three counties in three states (Cook County in Illinois, Dade County in Florida, and Jackson County in Missouri). They found that “women faced significantly lower odds of incarceration than men in all three jurisdictions” (Spohn and Beichner Reference Spohn and Beichner2000, 164). Nor is there evidence based on their analysis that this preferential treatment was reserved for white women. In two of their three sites, both white and black women were less likely to be sentenced to prison if convicted than men of either race, while in the third site, black women received more lenient treatment than only black men. Finally, they found that gender conditioned the effects of other legal and extralegal variables included in the analysis (ibid, 173).

To summarize, extant empirical research suggests that there are race-gender effects at both the conviction and sentencing stages of criminal trials, and that there are possible interactive effects with the defendant's sex and the victim's race. Further, to the extent that there is a consensus view in this literature, it is that women are treated more leniently by the courts than are men, which appears to contradict my argument.

Before I turn to the data to discriminate between the two sets of arguments described thus far, it is worth considering three weaknesses in the existing literature. First, most existing research on how gender and race affect legal outcomes focuses on sentencing decisions. Although sentences associated with particular crimes are associated with the seriousness society attaches to those crimes (Herzog Reference Herzog2006), there are a couple of reasons to be wary of an exclusive focus on sentencing. For one thing, courts and juries are increasingly constrained by mandatory sentencing guidelines, thereby suppressing some of the variation scholars are interested in explaining. Given such constraints, bias, if it exists, is more likely to be apparent at other stages in the legal process. For instance, given the subject matter of this article, defendants in a homicide case face two separate hearings in a court of law. The first concerns itself with the establishment of guilt, which, if demonstrated beyond a reasonable doubt, results in a conviction. The second hearing, which only occurs if the defendant is convicted, deals with determining the specific punishment, or sentence, to fit the crime. The crucial point, often overlooked, is that the second hearing is dependent on the first. That is, a defendant never faces a sentencing hearing unless he or she is first convicted of the crime. Therefore, if the conviction stage of the trial process is biased (or, more precisely, raced-gendered), then the sentencing stage is arguably problematic even if on the surface everything seems to be fine. Put simply, if the conviction stage is flawed, even an accurate sentencing might simply be assigning the right punishment to an unfairly convicted defendant. More generally, if the real locus of bias is at a stage prior to sentencing, studies examining only the sentencing stage might mistakenly conclude that no bias exists in the processing of criminal cases, especially as mandatory sentencing laws become more prevalent. To be clear, my point is not that women convicted of killing their alleged batterers are “unfairly convicted,” but rather that analyses of judicial outcomes can be misleading if only one stage of the judicial process is studied.

Second, most existing studies seeking to test theories of paternalism have pooled offenders in a variety of crimes, with “all felonies” in a given state being a frequent sampling rule. Given the relative rarity of female defendants in cases of violent crimes, the strategy of pooling offenders has the advantage of increasing the number of female defendants in the sample. The concern is that by pooling different types of offenders, scholars might miss more nuanced trends in the data. For instance, the argument presented in this article centers on violence, and it is quite possible that gender (especially) and race evince different dynamics in nonviolent cases. Women convicted of nonviolent crimes might in fact benefit from “paternalistic” judges, since their cases are less clearly transgressive of gender roles, or less threatening of sexual and racial hierarchies. This research design difference might help explain apparently conflicting findings in the literature on offender gender effects.

Third, even when scholars restrict their samples to violent crimes, or only homicides, no study of which I am aware accounts explicitly for the relationship between the offender and defendant. Yet men and women do not commit the same types of violence. Most violent crime in the United States is committed by men, who account for 85% of all homicides (Gauthier and Bankston Reference Gauthier and Bankston2004). The situation is reversed when one considers only the killing of intimate partners, such as spouses or cohabiting partners. In such situations, men and women have roughly the same rate of offense, and some studies suggest that women commit intimate partner homicide more frequently than do men (Gauthier and Bankston Reference Gauthier and Bankston2004, 97; see also DeWees and Parker Reference DeWees and Parker2003, 371; Swatt and He Reference Swatt and He2006). Why?

Existing explanations emphasize the nature of the crime. Unlike stranger homicide, intimate partner killing is often victim precipitated (Swatt and He Reference Swatt and He2006). Deaann Gauthier and W. B. Bankston (2004, 99) argue that homicide in modern societies can be understood as a form of “self-help social control,” which they define as “a response to perceived norm violations that does not involve formal third parties such as legal agents and indeed, is likely to be viewed as crime itself by those agents.” Such behavior, they continue, is most likely to occur in “stateless settings” where legal agents are relatively unavailable to serve as conflict mediators. One such setting is the domestic relationship, for all too often legal agents and law enforcement officials are loath to intervene in what they might regard as “private business.” In this situation, women who feel ignored by the law or society at large might well find themselves desperate enough to resort to lethal violence to resolve their situations once and for all (see Swatt and He Reference Swatt and He2006 for a similar analysis).Footnote 7 Indeed, as a purely empirical matter, more than half of all violent crimes by women fall into the category of intimate partner homicide (Shackelford Reference Shackelford2001). And more importantly, from a theoretical perspective, the type of violent crime more likely to be committed by women is central to existing social hierarchies, underscoring the importance of incorporating it into our analyses of gender effects in judicial decision making.

In the next section, I describe an original data set that allows me to address these concerns, and to test the hypotheses implied by the sexual stratification argument described in the previous section.

HOMICIDES IN OAKLAND COUNTY, MICHIGAN, 1986–88

Existing Research

One reason intimate partner killings have not been incorporated previously is a reliance on the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation's Uniform Crime Reporting data, and especially the Supplementary Homicide Reports (SHRs). As is well documented, these data, while providing large national-level samples for long periods of time, are limited in the type of information they include and in their coverage. Since provision of an SHR by a local official is voluntary, there exists considerable missing data that most scholars just ignore (Riedel and Regoeczi Reference Riedel and Regoeczi2004). More importantly, the SHRs do not report whether the case at hand involved any form of domestic violence. Although this information might be available in an individual case file, tracking such information down is extremely time intensive.

All data used in this article were collected by the Michigan Battered Women's Clemency Project. I gained access to the data by serving as a statistical consultant to the project from 2001 to 2002. These data are publicly available. In this section, I describe in some detail the considerations and procedures used in the data collection effort.

The sample analyzed in this article is of 82 homicide cases from Oakland County, Michigan, over the three-year period of 1986 to 1988.Footnote 8 The sample was generated by consulting police records for every homicide recorded in Oakland County during that period, which increases my confidence that I do not have any missing data that is systematic and that might bias the results of this project.Footnote 9 In addition, since my interests concern both the likelihood of conviction and the nature of sentencing for those convicted, generating the sample from the police records as opposed to court records has the advantage of including in the sample those cases that might not have made it to the courts because of insufficient evidence or other reasons (see Swatt and He Reference Swatt and He2006, 283 for a similar criticism of existing research).

Focusing simply on homicides makes good sense given the hypotheses outlined earlier in this article for a simple reason. As the most heinous of crimes, murder has received more public and governmental attention than other crimes, and prosecutors and judges abhor reputations of being soft on violent crimes. As such, any differences in conviction rates or sentencing should be at their minimum in such high-profile cases. Further, because rules about evidence and sentencing are least flexible in homicide cases, a sample of only homicides should be biased against finding any differences. To the extent, therefore, that the hypotheses receive any support in this sample, our confidence in their veracity is bolstered immeasurably.

Logistically, there is another important reason to choose to study homicide cases versus other felony cases. Although the Michigan State Police estimates that there were 129 homicides from 1986 to 1988 in Oakland County, there were 18,242 felony cases recorded in that same period in that county.Footnote 10 As described in the following subsection, the data collection effort required to incorporate information about domestic violence was extremely time intensive, making any sensible delimitation of the sample vital.

Collecting the Data

The Oakland County Court's coding system does not differentiate between homicides and other felony cases, making it impossible to separate the two ex ante. Therefore, it was necessary to have the defendant's name in every homicide case to find the court case number and pull the court file.Footnote 11

The Michigan State Police reported a total of 129 homicides for those years in Oakland County. The Oakland County Sheriff's Office, Prosecutor's Office, and Michigan State Police did not have a compilation of homicides by defendant or victim name, and neither did any other crime-reporting compilation required under state or federal law. Therefore, Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests were made to each of the 57 law-enforcement jurisdictionsFootnote 12 within Oakland County for incident reports of all homicides, suspects' full name, and the number of homicides within their jurisdiction between 1986 and 1988. This method was very successful and accounted for all of the 129 homicide cases in Oakland County.

The police records thus collected were used to compile demographic information about the defendant and victim. We collected data on the race, sex, and age of each defendant and victim.Footnote 13 Next, we established whether there existed a prior relationship between the defendant and victim, as well as the nature of that relationship. The suspect/defendant name was used to obtain the file number and to physically pull the original court file for each homicide; from each court file, we obtained sentencing and conviction information and filled in any missing relationship or demographic information.

Finally, more specific Freedom of Information requests were made to individual law-enforcement jurisdictions to obtain any data not received from the original FOIA requests or not found in the court files. Separate FOIA requests to the Oakland County Probation Office yielded sentencing-guidelines information when it was not present in the court file.

The research design thus took seriously Paul Allison's (Reference Allison2002, 2–3) admonition that “[t]he only really good solution to the missing data problem is not to have any. So in the design and execution of research projects, it is essential to put great effort into minimizing the occurrence of missing data.” I am confident that any missing data is completely at random and that there are no patterns of missing data that might call into question the validity of the results of this study.

Describing the Sample

As stated, the sample consists of 82 homicide cases that occurred in Oakland County, Michigan, between 1986 and 1988. Before I describe the pertinent characteristics of the sample, a brief discussion of the broader social context is in order. Located in the southeast corner of the state, Oakland County is one of the largest counties in Michigan. Its population in 2000 was 1.1 million (the state population was a shade under 10 million), of whom 10% had moved to Oakland in the past decade. Racially, Oakland County is different from the rest of Michigan: 82.80% of its population is white (compared to 80.20% for the entire state), 10% black (compared to 14.2%), and 4.1% Asian (compared to 1.8%). This racial composition hints at another difference between Oakland and the rest of the state. While the median household income in Oakland County in 1997 was $59,677, the state median was more than $20,000 less, and neighboring Wayne County, within which the city of Detroit lies, has a median household income of only $35,357. As with the rest of Michigan and the United States, income and race in Oakland County are highly correlated, so that being white is a robust indicator of one's income.Footnote 14

The sample of homicide cases under investigation in this article displays variations too, although these variations suggest far less prosperity and happiness than those just presented. In the 82 homicide cases for which data exist, 59% of the defendants are nonwhite (recall that non-whites are 17% of the total population), and 17% are women. The single largest group of defendants is black men (48% of the sample). Of the 14 female defendants in the sample, only four are white. The victim profile resembles that of the defendants. Most of the victims were nonwhite and male, with black men forming the largest proportion. Summary statistics for all variables included in the analysis are provided in Table 1.

Table 1 Variables used in the analysis

Consistent with previous research, the defendant and the victim in most dyads were at least acquainted with each other prior to the crime. Only one-fourth of the cases appear to have involved strangers. In fact, 15% of the cases involved dyads where the defendant and the victim had been intimate with each other. About a quarter of the cases involved domestic violence in some form or the other, and in 11% of the cases, the defendant had been a victim of domestic violence at some point. This last statistic is misleading, however, and masks a large gender difference: None of the male defendants were victims of domestic violence, but 64.29% of the female defendants were victims.

The sample includes 14 women.Footnote 15 Of these, seven were arrested for killing their alleged batterers. Of the other seven, one was a 20-year-old accused of killing her baby, and the other (also 20 and black) was accused of killing an 81-year-old white pastor she found abusing her daughter. Four of the remaining five were accessories to murder committed by men, including one who was involved in her husband's murder of his stepmother. The final woman, a 23-year-old black woman, was arrested for killing a 20-year-old romantic rival. This profile of the women in the sample underscores the point made in the previous section. Women homicide defendants are far more likely to have been intimate partners or family members or accessories to male-precipitated violence than are their male counterparts.

These data clearly contain sufficient variation on the variables of interest to tackle the questions posed in the previous section: Are women treated differently by the judicial system? What role does intimate-partner killing play? In the next section, I present results from a multiple regression analysis.

MODEL SPECIFICATION AND RESULTS

The statistical analysis considers two dependent variables: probability of conviction and sentence severity.Footnote 16 Coding the conviction dependent variable is straightforward: “1” indicates that the defendant was convicted while “0” indicates that he or she was acquitted. Coding the sentencing variable, by contrast, was more complicated. Sentences are defined by ranges, rather than an exact number of years, allowing for parole. I use the lower end of the range as the relevant threshold by which to construct the sentencing variable. Thus, the sentencing variable is categorical but ordered, so that “1” is for sentences with minimum sentences ranging from probation to 10 years, “2” is for minimum sentences of 10 to 25 years, “3” is for minimum sentences of 25 years to life with parole, and “4” is for sentences of mandatory life (i.e., life without possibility of parole).Footnote 17

In the regression analysis, I control for the defendant's race (White = 1) and sex (Female = 1) as well as the interaction between the two (see McCall Reference McCall2005 and Weldon Reference Weldon2006b on the use of interaction terms to study issues of intersectionality). I thus use what S. Laurel Weldon (Reference Weldon2006b) terms an “intersectionality-plus” approach.

The victim's race and sex are also included. Due to the small sample size, I was unable to include the interaction of the victim's race and sex. As a proxy for socioeconomic status, I control for whether the defendant used a court-appointed attorney or hired a private attorney (Private = 1). The defendant's prior criminal record, if any, is also included in the model. I also account for whether this was a bench trial, as opposed to trial by jury, since previous scholars have suggested that judges might be more prone to paternalistic attitudes than juries (Daly Reference Daly1987, Reference Daly1989). For the sentence severity analysis, I include also the severity of the charge on which the defendant was convicted, since that should bear closely on the sentence. Finally, I include two variables for the nature of the relationship between the defendant and victim. The first such variable, Intimate, captures whether the defendant and victim had an intimate, sexual, dating, or romantic relationship. The second gets more specifically at whether this is a case in which the defendant is accused of killing her batterer.Footnote 18

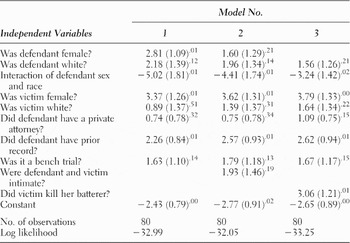

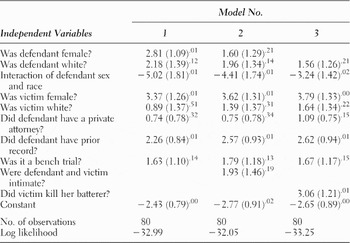

Table 2 reports the results from a logit analysis of the probability of conviction. Model 1 in Table 2 provides a baseline model in which the only controls are for the basic demographic characteristics of the defendant and victim, as well as for whether the defendant used a private attorney, had a prior criminal record, and chose a bench trial. Model 2 then adds to this base model a variable capturing whether the defendant and victim had intimate relations. Model 3 asks more specifically if whether the defendant is accused of killing her batterer made any difference. What do these models reveal?

Table 2 Logit analysis: Probability of conviction

Note: Standard errors in parentheses with p-valuessuperscripted.

A striking result in Table 2 is the importance of the interaction of the defendant's sex and race for the outcome of the trial. Black women have a statistically significant higher probability of being convicted, while white women have a statistically significant lower probability of being convicted. Assuming that the victim was a black male, which was the modal case, the probability of a white female defendant being convicted was 0.078, while the probability for a black female defendant being convicted was 0.6.Footnote 19 Note that since the reference group here is black men, the coefficient on “Is the defendant white?” reveals that there is no statistically significant difference between white and black men in the probability of being convicted.

The victim's gender is also very important. Holding the race and gender of the defendant constant, cases with female victims were always more likely to result in convictions, which is consistent with previous arguments about a victim gender effect in the judicial system. It is interesting that the race of the victim does not have a statistically significant effect on the probability of conviction. It bears noting that, all else equal, cases with white victims always have a higher probability of conviction than those with black victims, with the difference in probability ranging from 0.09 to 0.22, depending on the hypothetical defendant. Defendants with court-appointed attorneys do not appear to do any worse than those with private attorneys, and whether the case was heard by a judge or jury has little effect; however, there is a very strong positive effect on the probability of conviction for defendants with prior criminal records.

Adding the two variables concerning the relationship between the defendant and victim does not alter any of the effects of the control variables, which allows me to focus my discussion of Models 2 and 3 in Table 2 on them alone. First, did it matter if the defendant and victim had been intimate with each other? My analysis suggests not; this variable has a positive coefficient but it is not statistically significant.

What about cases in which a woman was arrested for killing her batterer? Here, I reach a different conclusion. The coefficient on this variable is large, positive, and highly statistically significant. These women faced a much higher probability of conviction. One of the hypotheses generated by the sexual stratification argument I have presented is that the treatment of women who kill their batterers should differ depending on their race. Specifically, I hypothesized that black women should be at a disadvantage compared to white women. Figure 1 shows the estimated probability of conviction for four hypothetical female defendants. The main manipulation is altering whether the case involved the defendant killing her alleged batterer or not. All other factors are held constant. In the following simulation, the victim is assumed to be a white male; if this is changed to a black male, the probability of conviction drops for all four cases.

Figure 1 Probability of conviction.

The results of this simulation—based on the results from Model 3 in Table 2—are striking. For both black and white women, killing one's batterer raises the probability of conviction significantly, in both substantive and statistical terms. When all factors are held equal, black women have a higher likelihood of conviction than white women, even after controlling for the principal facts of the case. The data thus clearly illustrate the power of the sexual stratification hypothesis and of the intersectionality perspective for understanding the workings of the justice system in the United States.

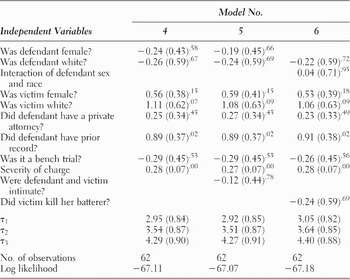

Turning to the sentence severity analysis, Table 3 reports the results from an ordered probit analysis of the severity of the sentence handed down if the defendant is convicted.Footnote 20 And, again, they are quite instructive. As one might expect (and probably hope), two factors that are consistently important across all three models are whether the defendant had a prior criminal record, which here increases the likelihood of a more severe sanction, and the severity of the charge on which the defendant was convicted, which also has a positive effect on sentence severity. Both factors have a clear legal rationale underlying them and would clearly be relevant at the sentencing stage. In contrast, the variables for the relationship of the defendant and victim included in Models 5 and 6 are both statistically insignificant, indicating that neither factor adds explanatory power to the model, given the other included control variables. This result is not altogether surprising, given the use of mandatory sentencing guidelines in Michigan. Beyond this point, however, it is important to remember that unlike most other studies that focus on sentencing outcomes, this article focuses exclusively on convictions for homicide cases; the range of sentencing outcomes is necessarily limited because in all the cases, defendants have been convicted of the same crime. Future studies should consider other ways in which the harshness of the penalty might be manipulated, for instance, in the granting of parole.

Table 3 Ordered probit analysis: Sentence length

Note: Standard errors in parentheses with p-valuessuperscripted.

Less explicable from a purely legal standpoint is the finding that cases in which the victim was white had a higher probability of receiving a longer sentence. Figure 2 plots the predicted probability of a hypothetical defendant receiving a sentence of 25 years to life with the possibility of parole, or mandatory life in prison.Footnote 21 The results of this hypothetical exercise are really quite remarkable. Holding all the other factors constant, the cases with a white victim have a higher probability of the more severe sentence. Within each victim race category, the black defendant has a higher probability of a more severe sentence; within each defendant-victim-racial dyad, the female defendant has a lower probability, albeit only marginally so. Further, note that the probabilities attached to black female defendants is virtually identical to those attached to white male defendants—lower than black males but higher than white females. As anticipated by an intersectionality perspective, the experience of the hypothetical black woman in this simulation is captured by neither her race nor her gender, but rather by the interaction of the two.

Figure 2 Probability of receiving a sentence of 25 years or longer.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This article uses an original data set to investigate gender and race effects in the U.S. justice system's treatment of homicide cases. There are three principal findings. The first is that the defendant's gender and race have an important interactive effect on the probability of conviction. Black women have a higher probability of being convicted, while white women have a lower probability. In the context of an enormous and well-established literature on the intersectionality of race and gender, this finding adds empirical evidence of its importance for women in the court system.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the second analysis of sentence severity. Black defendants have a higher probability of receiving the highest sentences, all other things equal, than their white counterparts. And the race of the victim matters significantly. Defendants convicted of killing a white person are far more likely to get a severe sentence than are those convicted of killing a black person.

Finally, the article presents the first systematic evidence of which this author is aware for the importance of taking seriously the nature of the relationship between the defendant and victim. Women defendants are far more likely to be arrested for the homicide of an intimate partner or family member than for a stranger. And domestic violence is much more likely to be part of a female defendant's case. Given these facts, my finding that women arrested for killing their batterers are far more likely to be convicted, even when controlling for legally relevant factors and demographic characteristics, is troubling.

Put together, these findings lend support for the sexual stratification argument that structures this analysis. Specifically, that argument hypothesized that women who kill their batterers should be treated severely by the court system since their actions threaten existing sexual hierarchies in a society that accords men dominance over women. Even as the women's movement has eroded the overt exercise of this dominance in the public sphere, the private sphere remains a last bastion for patriarchy. And the strong positive and statistically significant coefficient in the conviction model for the defendant-killed-her-batterer variable supports this contention. The second testable implication, derived from the intersectionality perspective, is that violence against women is treated differently depending on the race of the woman in question. White women are accorded a higher status in this society and deemed more worthy of protection than are black women. As such, my argument predicted that black women accused of killing their batterers would be treated more harshly than white women in the same situation. Again, the data are very supportive of this claim, though the very small cell sizes make it difficult to distinguish clearly among the effects of race, gender, and abuse allegation. A final testable implication of my argument was that black women who kill white male batterers would be treated most harshly, while white women accused of killing black male batterers would be most likely to benefit from leniency. The absence of any interracial pairs in these data makes a direct test of this hypothesis infeasible, but it remains an interesting avenue for future research.

Three caveats are worth considering in evaluating the contributions of this article. Most troubling for my argument is the counterargument that cases involving domestic abuse are particularly easy to adjudicate for courts, given the facts of the case. It might certainly be true that women with limited resources are more likely to find themselves without access to formal third-party conflict resolution opportunities and, therefore, more likely to require self-help social control. Indeed, considerable research has documented that homicide by women is more often in self-defense or in protection of children (Gauthier and Bankston Reference Gauthier and Bankston2004). This type of self-help behavior is itself regarded as criminal by the authorities, however, and at least two factors make it unlikely to be viewed sympathetically.

First, research on victims of domestic violence consistently finds that judges, prosecutors and other legal authorities often question victims' decisions “not to leave their abuser.”Footnote 22 Such a position misrepresents the victim's position. Not only might a battered woman be afraid to take such a step, but most also seek to end the violence in the relationship, not the relationship itself. And such a tack of questioning comes dangerously close to sounding like “she deserved it” or “she was asking for it” or “it couldn't have been so bad or she would have left him.” In any of these forms, the reaction is likely to be quite disempowering for women and, worse, its anticipation might make battered women less likely to seek outside help. Second, unlike the prototypical case of self-defense, where someone reacts in the instant to an attack, intimate partner killing in the context of domestic violence is more likely to appear to be premeditated to the outside observer (Swatt and He Reference Swatt and He2006). Women being abused are rarely strong enough to fight back while they are being beaten. More commonly, the abuse eventually becomes so unbearable that the victim begins to fear for her life. Then at some moment when her abuser is unguarded, she might seize her opportunity to do something. This syndrome now goes by the name of “battered woman's syndrome” (BWS).Footnote 23 And there's a further problem, since the very nature of a defense based on BWS begins with an admission of the “facts of the case,” making it difficult for judges or juries not to convict a defendant.Footnote 24

While these concerns are certainly valid, I would argue that they actually help make the larger point in this article. It is certainly true that intimate partner killings, and killings of alleged batterers specifically, lend themselves to easier convictions. But since women—and poor black women even more so—are systematically more likely to find themselves in such situations, ignoring this fact is to ignore the role that gender, race, and class play in structuring these situations. For the justice system to be “blind” to such considerations therefore results in what Mary Hawkesworth (Reference Hawkesworth2003, 537) terms “racing-gendering.” Hawkesworth states that “[t]o speak of an institution as raced-gendered is to suggest that race-specific constructions of masculinity and feminity are intertwined in the daily culture of the institution.” Or, to use Karen Beckwith's (Reference Beckwith2005, 132) formulation, “gender as process is manifested as the differential effects of apparently gender-neutral structures and policies upon women and men.” Applied here, these ideas challenge theorists to start thinking of the judicial system as raced-gendered, since its dominant patterns of thinking presume a male-centered view of violence (involving strangers and a clear distinction between attacker and victim) and ignore the possibility of a different dynamic underlying cases of homicide with female defendants (involving intimate partners and an ambiguous and situational distinction between attacker and victim; see Swatt and He Reference Swatt and He2006 on the latter point). Similarly, opportunities exist to analyze the development of ostensibly neutral rules of evidence or sentencing guidelines as raced-gendered institutions.

The second and third caveats concern the data used in this article. The data suffer from two linked limitations: small sample size and problems of generalizability. The analysis presented here is based on a sample of 82 homicide cases in Oakland County, Michigan, from 1986 to 1988. Maximum-likelihood estimation techniques, such as those utilized in this article, typically assume at least two and a half times that many data points, which suggests that caution is recommended in assessing these results, since they might be unstable. Further, the small number of female defendants, and the even smaller number of them involved in domestic-violence situations, limits the power of the analysis for distinguishing between alternative effects.

The second data limitation is that the cases here are drawn from a single county in Michigan. As noted, Oakland County is richer and slightly whiter than the rest of Michigan (and, indeed, than the United States as a whole). To the extent that one believes the sexual stratification hypothesis, then, it is also true that it should be more likely to be true in Oakland County and that its effects should be less pronounced in areas of the country where white men are not the predominant group. While this concern certainly suggests that concerns about the generalizability of these results are valid, I believe that this is ultimately an empirical question, and I urge future researchers to subject the argument presented here to tests on larger and more general data sets.

Given that most research on questions concerning how homicide cases are adjudicated is conducted in the discipline of criminology, it is hardly surprising that the greatest attention is paid to legally relevant factors. Ignoring the context within which crimes are committed, however, means that we miss potentially important information about how gender enters the picture. All crimes are not equally likely to be committed by each gender. Women are far more likely to be in the court system as defendants in violent crime cases because they were defending themselves against an alleged batterer, and because they lacked the resources to extract themselves from an unhealthy relationship. Ignoring these facts, I have argued, has important legal and gendered consequences; I hope this article will motivate more scholarly attention to be paid to theorizing the political consequences of how crime is gendered.Footnote 25

One change in the U.S. legal landscape over the past 15 years has been the greater recognition of such questions and increased debate about the validity of battered woman's syndrome as an admissible defense in criminal trials. The debate over BWS and its acceptance or rejection in courts is an inherently political question that should provide leverage for political scientists interested in understanding the role of gender in the making of public policy; explaining variation in rules governing BWS remains ripe for further research.Footnote 26

Seventeen years after her arrest, Karen Kantzler remains in prison. Numerous appeals by her lawyers to introduce the history of the battering she suffered have been rejected by the courts. At her sentencing hearing, and at subsequent appeal hearings, the presiding judges have consistently expressed sympathy for the situation in which she found herself, but have admonished her for not “seeking a separation or divorce.”Footnote 27 The Michigan Battered Woman's Clemency Project continues to petition for a new trial on her behalf.