The last several decades have seen a significant rise in the number of women gaining access to political institutions in the United States. Since the early 1970s women have increased their numbers in the United States Congress by more than sixfold, and now hold 19 percent of the seats in the US House and 20 percent of the seats in the US Senate. While still far short of parity, the increase in female representation has spurred many questions about what differences, if any, exist between male and female legislators.

The scholarly literature that engages these questions has suggested that gender is an important variable for explaining political behavior and legislative interactions in areas such as leadership styles (Jewell and Whicker Reference Jewell and Whicker1993; Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal1998), constituency service (Thomas Reference Thomas1992; Richardson and Freeman Reference Richardson and Freeman1995), communication patterns in hearings (Kathlene Reference Kathlene1994), and (most extensively) the policy priorities of female legislators. Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge2005, 622) offers a parsimonious summary: “descriptive representation by gender improves substantive outcomes for women in every polity for which we have a measure.” All said, there is an underlying assumption in much of this literature that as the number of women in Congress increases, so, too, will the substantive representation of women.

If the increasing numbers of women are to have a major impact on the nature of the policies Congress addresses, however, certain conditions must be met. First, women in Congress must have different goals or agenda items than do men. Second, women must be able to use their interest and expertise in such “women’s issues” to translate their proposals into law. Third, women must help transform the institution of Congress into one that is more open to and friendly toward women’s issues.Footnote 1 Whether these three conditions are met in Congress remains an open question, one which we seek to address. More specifically, we ask: are there issues that women in Congress dedicate greater attention to than do men? On such “women’s issues,” are the attention and expertise of women rewarded with a greater likelihood of their proposals becoming law? And, is the Congress biased in favor of (or against) the enactment of legislation on women’s issues? The collective answers to these three questions offer an overall assessment of how women in Congress have changed the nature of policies advanced and adopted.

Our approach is especially novel given the way that the link between descriptive representation and substantive representation has been conceptualized within the gender and politics literature. Specifically, scholars have typically studied this link by tracking bill introductions and/or votes of a sample of bills that they designated ex ante as “women’s issue” bills. While this approach has a strong theoretical basis, the result is that the definition and operationalization of “women’s issues” can vary substantially, depending on the scholar undertaking the analysis. Moreover, by selecting only women’s issues, no comparable baseline of other issues is considered to better gauge the actions and effectiveness of women across all possible issues.

In contrast, rather than beginning with a presumed definition of women’s issues in Congress, we employ a novel data set to examine all 151,824 public bills (H.R.s) introduced across all 19 major issue areas in the US House of Representatives over four decades (1973–2014). We identify women’s issues as those on which women introduce significantly more bills than do men, and we compare the lawmaking success of women on these issues to their success elsewhere, to gauge whether women are rewarded for their efforts and expertise. Finally, we identify various institutional features of Congress that might contribute to these findings.

While our approach for defining women’s issues and tracking their fates across all bills introduced over 40 years is quite expansive, to provide the broad brush strokes offered here, we necessarily set aside many finer details of policymaking. For example, our substantive categories are rather broad. Whereas other studies may code bills dealing with abortion policy as distinct from contraception policy, our classification places them both in the general category of Health (with each bill assigned to only one general category). Similarly, our approach does not allow us to decipher the ideological dimensions or policy directions of each bill. In addition, although our quantitative approach provides an important perspective on women’s issues in Congress, it prohibits us from accounting for such things as conversational dynamics in committee or self-reports about gendered interactions (e.g., Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003), which also shed light on the policy impacts of female lawmakers’ legislative strategies. We believe that our study complements such qualitative scholarship; and taken together, these different methodologies can present the most complete picture of the role that women play within legislative institutions. Finally, as our data are focused solely on the US House, we cannot speak to the policy impact of women in the US Senate or other legislative bodies; we hope that our approach will be applied more broadly in future work.

Defining Women’s Issues

As alluded to above, much of the literature concerning representation and women has focused its attention on the substantive benefits of descriptive representation. Underlying this research are notions that there is a definitive collection of “women’s issues,” that these issues arise because women in politics “act for” women in the public, and that women’s interests and issues can be systematically characterized and quantified (Baldez Reference Baldez2011).Footnote 2

Building on this premise, many scholars of substantive representation have investigated whether distinct differences between the policy priorities of male and female legislators exist. A pervasive finding in this literature is that, even after controlling for a host of other factors, female representatives are more likely to care about, sponsor, and vote for women’s issue bills. While scholars are in general agreement regarding female legislators’ propensities to advance women’s issues, less agreement can be obtained regarding what, precisely, constitutes a women’s issue,Footnote 3 as numerous definitions and operationalizations have been advanced.

One approach has been to use external sources to delineate the boundaries of women’s issues. Dolan (Reference Dolan1998) and Swers (Reference Swers2005), for example, define women’s issues as those that are supported by the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues. Frederick (Reference Frederick2011) and Swers (Reference Swers1998, Reference Swers2002a, Reference Swers2005) consult groups such as the American Association of University Women. Cowell-Meyers and Langbein (Reference Cowell-Meyers and Langbein2009) look to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Other scholars (e.g., Welch Reference Welch1985; Burrell Reference Burrell1994; Reingold Reference Reingold2000) define women’s issues to be those that create a demonstrable gender gap in public opinion.

Another approach has been to define women’s issues in more theoretically based terms, such as arguing that women’s issues are those issues that are “particularly salient to women—either because they primarily, more directly, or disproportionately concern or affect women in particular or because they reflect the more ‘traditional’ concerns (or interests) that women presumably have about others” (Reingold and Swers Reference Reingold and Swers2011, 431). While this approach does not rely on external sources to categorize issues, it still raises potential measurement concerns. More specifically, scholars employing such an approach must make ex ante judgment calls regarding whether they operationalize women’s issues as those policy areas that are explicitly about women (e.g., sexual discrimination), those policy areas that have conventionally been associated with women or the private realm (e.g., children and families), or those that aim for feminist outcomes (e.g., establishing fair pay). Taken together, it should be unsurprising that a multitude of issues, such as abortion, women’s health, childcare, education, discrimination, welfare, family leave, and general healthcare have all, at times, been categorized as women’s issues.

Reingold and Swers critique the current scholarly approach:

all of these attempts to define and measure women’s interests and issues have one thing in common: none relies on the subjects of inquiry (elected officials, in this case) to define (actively or passively, directly or indirectly) … their own conceptions of women’s interests/issues. Instead, each of us has defined our terms exogenously, assuming perhaps that our primary task or challenge as researchers is to create a priori a valid, defensible, and appropriate definition of women’s interests/issues (Reference Reingold and Swers2011, 431–2).

As a result, “no matter how careful, conscientious, or inclusive [scholars] may be, [they] still risk some degree of oversimplification or overgeneralization” (Reingold and Swers Reference Reingold and Swers2011, 432).

In a departure from past practice, we embrace Reingold and Swers’s implicit suggestion of allowing female lawmakers themselves to define what they consider to be women’s issues.Footnote 4 Specifically, we label an issue as a women’s issue if women in Congress are more likely than men to raise the issue or if women raise the issue in a greater volume than do men. These self-defined women’s issues therefore need not match those of the prior literature. (Given the scope and breadth of previous research, however, we believe it likely that the extant scholarship has been closely related to female legislators’ actual areas of interest.)

To undertake our analysis, we employ a data set that identifies every public bill (H.R.) introduced into the US House from the 93rd–113th Congresses (1973–2014), categorized by substantive issue area, and tracked from bill introduction to enactment into law. By analyzing all of the 151,824 bills that were introduced during this time period, we are able to identify the substantive areas (and quantities) of the bills that female and male legislators introduced, and assess how far these bills advanced across different stages in the legislative process.

Although there are a number of different ways that one could categorize each bill, we adopted the issue classification protocol of Baumgartner and Jones (Reference Baumgartner and Jones2002) in which each bill (from the narrowly tailored to the massive omnibus) is assigned to one (and only one) of 19 major topics. This coding scheme has been incorporated into several substantial research projects, including the Policy Agendas Project of Bryan Jones, John Wilkerson, and Frank Baumgartner (www.policyagendas.org), and the Congressional Bills Project of Scott Adler and John Wilkerson (www.congressionalbills.org).Footnote 5 The Congressional Bills Project has manually classified bills according to the coding system of the Policy Agendas Project; and it is from this data set that we categorize our bills into issue areas. We begin with the 93rd Congress, as this is the first Congress tracked by the Library of Congress website, from which we draw information about bill sponsors and the progress of bills through the lawmaking process.Footnote 6 We end our analysis with the 113th Congress (2013–2014), the most recently completed Congress. We focus on the 19 major topics to offer a comprehensive overview of issues in Congress over three decades. Future work replicating our approach on sub-topics within these major categories would be welcome, and may well identify further important variation within the women’s issues identified here.

After categorizing each bill into one of the 19 issue areas, we then identified (for each issue area) the percentage of women who introduced bills, the percentage of men who introduced bills, the average number of introductions by women, and the average number of introductions by men.Footnote 7 We display these percentages and averages in Table 1, highlighting differences that are statistically significant based on χ 2 tests.

Table 1 Bill Introductions by Issue Area

Note: Italicized issue areas are hypothesized to be “women’s issues,” based on prior scholarship.

**p<0.01, *p<0.05, on differences across genders, shown next to gender with higher value.

The seven italicized issues in the table are those most commonly characterized as women’s issues in the extant literature.Footnote 8 Of those seven issues, six display significant patterns. Specifically, 26.5 percent of women introduce Civil Rights & Liberties bills, compared with 19 percent of men; 65.4 percent of women introduce bills in the Health issue area, versus only 48.3 percent of men; and 49.8 percent of women sponsor Law, Crime & Family legislation, compared with 39.2 percent of men. There are also nearly 10 percentage point gaps for Education and for Labor, Employment & Immigration. Housing & Community Development features a nearly 4 percentage point gap between men and women; and Social Welfare bills feature equal rates of sponsorship by men and women.Footnote 9 In terms of the numbers of bills an average member introduces in each Congress, women are significantly more prolific on Education, Health, Housing & Community Development, and Civil Rights & Liberties.Footnote 10

In contrast, there are seven issue areas in which either a larger percentage of men introduce bills or men introduce a greater number of bills on average, at a statistically significant level.Footnote 11 Such differences are most dramatic in Agriculture, Energy, and Macroeconomics, areas in which the average man introduces almost twice as many bills as the average woman. None of these issue areas is among those typically listed as women’s issues in the existing literature.

In sum, we find significant (although not complete) overlap between issues classically studied as “women’s issues” in the current literature and those major issue areas addressed more frequently and in greater numbers by women in their sponsored legislation over the past four decades. For the purposes of tracking the fates of such proposals, we are therefore comfortable defining the following six areas as women’s issues for the remainder of this study: Civil Rights & Liberties; Education; Health; Housing & Community Development; Labor, Employment & Immigration; and Law, Crime & Family.Footnote 12 Each of these six areas features a larger percentage of women sponsoring bills, a larger average number of bills sponsored by the average woman, and at least one of those differences attaining statistical significance (p<0.05).Footnote 13 Consistent with the prior literature, there may be a variety of reasons why women introduce more legislation in these areas. For example, as with all legislators, women may simply introduce more bills in areas about which they themselves care the most. Moreover, women may feel an additional responsibility to represent women generally, even beyond the concerns that would normally arise from their own preferences and district concerns. Regardless of the reason, the work here establishes that quite similar patterns of women’s issues arise through our new method as through the approaches used previously in this literature.

Theoretical Considerations

Expertise and Lawmaking Success

Having established that women specialize in particular issue areas, we now explore whether women experience enhanced legislative success in correspondence with their interests and expertise. Theoretically, there are several reasons why one might expect women’s issue specialization efforts to yield such benefits. Previous research has demonstrated that female politicians are viewed as better suited to handle issues such as social welfare and healthcare, whereas male politicians are considered experts in such areas as economics and business (Leeper Reference Leeper1991; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993a; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993b). On this point, interview data suggests that “both female and male representatives [feel] that women in elected office have a better sense of how to develop and implement feminist policy as a result of their life experiences” (Tamerius Reference Tamerius1995, 102). If female legislators are recognized to be experts in particular issue areas (either because they can draw on their own personal experiences, or because they have cultivated a body of expertise through extensive research and outreach), then informational theories of legislative organization (e.g., Gilligan and Krehbiel Reference Githens and Prestage1987; Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel1991) would suggest that the House would defer to these legislators’ expertise in these policy areas. As a result, legislators (including male legislators) may be more willing to support bills that are introduced by women if they fall within one of these women’s issue domains.Footnote 14

Consistent with this view, several studies have identified a pattern of deference in US state legislatures, whereby women appear to be more successful than their male counterparts at advancing bills that engage women’s issues. Thomas (Reference Thomas1991), for example, finds that bills pertaining to women, children, and families had a success rate of 29 percent when introduced by women, but only 13 percent when introduced by men; and Saint-Germain (Reference Saint-Germain1989, 965) finds that female state legislators have better rates of success in advancing women’s issues bills than do men. Hence, one might expect that female legislators in Congress would be similarly rewarded for their specialization efforts, particularly if they specialize in bills that engage women’s issues, which serves as the motivation for the following hypothesis:

Expertise and Lawmaking Success Hypothesis: Women are more successful than men at converting women’s issue proposals into law.

Institutional Biases

In contrast to the above hypothesis, the findings from state legislatures may not generalize to all legislatures, nor to the US Congress in particular. That is, while female members of Congress may specialize in women’s issues, they might not receive deference and enhanced legislative success in these areas. As noted by Githens and Prestage (Reference Gilligan and Krehbiel1977, 399), politics has long been considered a “man’s business,” and thus, female legislators may face a unique set of institutional hurdles due to their gender. A survey of state legislators found, for example, that approximately one-quarter of all women have concerns about institutional discrimination, citing issues such as the “isolation of women members,” and trouble “having my male counterparts deal with me on their level” (Thomas Reference Thomas2005, 252). Similarly, Kathlene (Reference Kathlene1994) offers evidence of gendered patterns in legislative committee hearings, where men were much more likely to interrupt and talk over female legislators than over their male counterparts. Thus, while “legislative egalitarianism” might follow from formal congressional rules (Hall Reference Hall1996), informal practices continue to impact social interactions and policy processes.Footnote 15

Such considerations may lead to two distinct institutional biases. First, women themselves may find their proposals dismissed at a greater rate than do men. Whether because they are raising issues that do not resonate with men, and thus with the vast majority of lawmakers, or whether their proposals are taken less seriously for other reasons, women may be less effective as lawmakers than are men. Second, the issues that women care about the most may be dismissed more easily in male-dominated institutions than are the issues that men care about the most. Raising new issues and introducing a new agenda may be of little use if women’s issues are then immediately bottled up in committee, never voted upon, never enacted, and thus never actually allowed to address the needs of the constituents that women are seeking to represent.Footnote 16

On the question of overall effectiveness, the existing literature tends to point to the enhanced effectiveness of women (e.g., Saint-Germain Reference Saint-Germain1989; Bratton and Haynie Reference Bratton and Haynie1999; Jeydel and Taylor Reference Jeydel and Taylor2003; Anzia and Berry Reference Anzia and Berry2011; Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer Reference Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer2013; but see Lazarus and Steigerwalt Reference Lazarus and Steigerwalt2011). However, such research tends to focus either on a small subset of issues or on lawmaking as a whole. We believe it is important, instead, to assess the effectiveness of women on the wide range of women’s issues, set in contrast to their effectiveness on all other issues and to the comparable effectiveness of men. More specifically, the existence, extent, and nature of any gender bias in Congress can be explored through the following hypothesis, based on our approach to defining women’s issues and tracking their progress through the lawmaking process.

Institutional Bias Hypothesis: Women’s issues and the proposals offered by female lawmakers are less successful in moving through Congress and into law than are the proposals offered by male lawmakers.

Empirical Approach and Findings

The Fates of Women’s Issues

To test the Expertise and Lawmaking, and Institutional Bias hypotheses, we calculated bill success rates for women and men, where bill success is equivalent to the frequently examined “hit-rates” characterizing the percent of introduced bills that become law (e.g., Box-Steffensmeier and Grant Reference Box-Steffensmeier and Grant1999; Jeydel and Taylor Reference Jeydel and Taylor2003). Unlike a typical “hit-rate” analysis that looks only at aggregate conversion rates, however, our analysis also identifies whether there are gender differences across each issue area. We first explore these issues with aggregate summary statistics, before ultimately treating each bill as a separate observation in logit regression analyses.

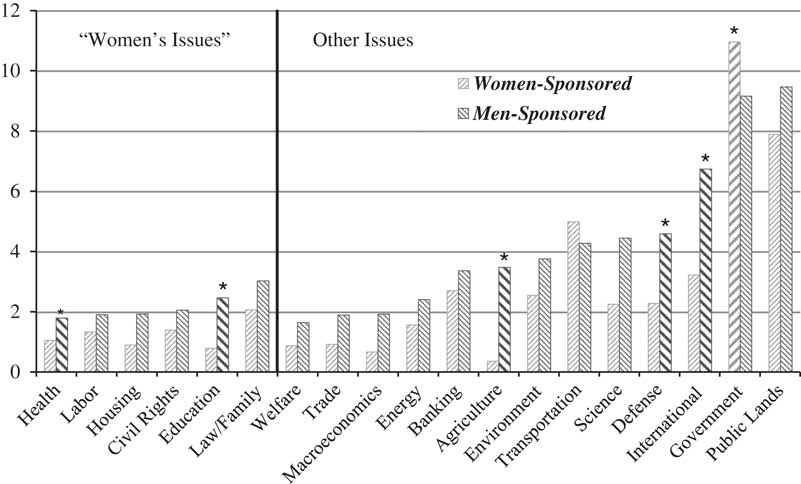

We begin by analyzing the bill success rates of women and men by issue area, where success is defined as the percentage of bills introduced that ultimately become law. In Figure 1, issues are grouped into women’s and other issues, and then organized from the most gridlocked to the least. The more darkly shaded and starred columns represent a statistically larger success rate for the starred gender in the particular issue area.

Fig. 1 Percent bill success rate, by issue type and gender of sponsor Note: Column heights show percent of sponsored bills that become law. Darker shaded, starred (*) columns represent gender with statistically significant greater success (p<0.05).

Three major findings are illustrated in Figure 1. First, men have a greater success rate than do women. For 17 of the 19 issues, men convert a larger fraction of their sponsored bills into law. In five of those areas, the enhanced lawmaking success of men is statistically significant (p<0.05). In only Government Operations are women statistically more successful than men.Footnote 17

Second, in the six areas we label as women’s issues, men are more successful than women for all of them. In two of these cases (Health and Education), women are statistically less successful than men. For example, 1.8 percent of Health bills sponsored by men become law, whereas only 1.1 percent of those sponsored by women become law. Collectively, this is strong evidence against the Expertise and Lawmaking Success Hypothesis. Indeed, based on this figure, the only reason why women may alter the production of women’s issues in Congress is because they sponsor so much more legislation in these areas. For example, women on average sponsor more than 50 percent more bills than do men on Civil Rights & Liberties. Because their success rate is more than two-thirds that of men, the net result is a small increase in laws in this area. However, any such differences are not statistically significant.

Third, women’s issues are among the most gridlocked of all issues in Congress. Of all 151,824 bills introduced between 1973 and 2014 in the House, 6163 became law, for an overall success rate of 4.1 percent. However, the success rate for women’s issues is about half that, at 2.1 percent. Moreover, the most gridlocked “Other Issue” is Social Welfare, which is commonly deemed to be a women’s issue by previous scholars.Footnote 18 These results provide strong support for the Institutional Bias Hypothesis. In short, the bills sponsored by women, and the issues that they care the most about, are systematically more gridlocked than are male-sponsored bills.

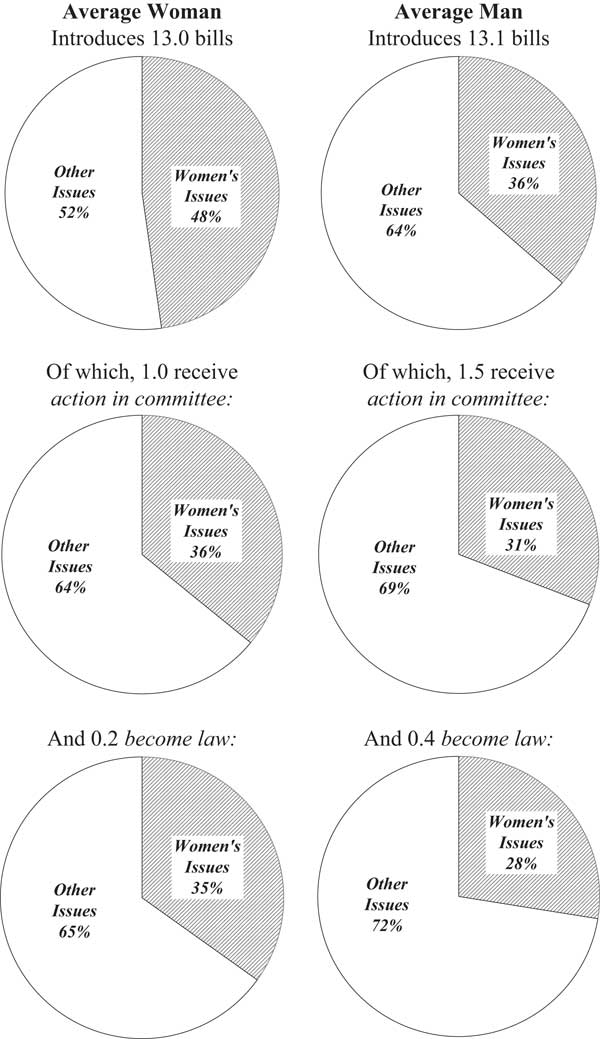

Put another way, the legislative portfolio of women in Congress is made up of a large proportion of women’s issues at the bill proposal stage. Moving through the lawmaking process, however, those women’s issue bills fall away at a greater rate than do other bills, leaving congresswomen little further along in advancing issues important to American women than are congressmen. We illustrate this process in Figure 2.

Fig. 2 Share of women’s issues at different lawmaking stages (excluding Government Operations and Public Lands)

The top set of pie graphs show the proportion of women’s issues among the bills sponsored by women (on the left) and men (on the right). In constructing these figures, we excluded bills on Government Operations and on Public Lands. Both are outliers in terms of the large number of bills advanced and laws produced, and neither is representative of the types of substantive issue areas discussed in the expansive literature on women’s issues.Footnote 19 Setting these issues aside, we see that across the 40 years of our study, men and women each sponsor about 13 bills/Congress. While nearly half of those bills sponsored by women raise women’s issues, that proportion is about one-third for men.

To assess these bills’ fates, we tracked the proportion of each type of bill through four additional major stages of the lawmaking process: (1) did the bill receive “action in committee,” in terms of hearings, bills markups, and subcommittee votes; (2) did the bill make it out of committee and onto one of the legislative calendars; (3) did the bill pass the House; and (4) did the bill become law? Of these, the critical stage in translating the aspirations of women into their legislative accomplishments is whether their bills immediately die in committee or whether they receive some form of action there. Following that stage, the proportion of women’s issues to other issues changes very little, right on through the passage into law.

As such, the second row of pie charts in Figure 2 shows how the mix of bills changes in the committee process. Before discussing the changing proportions, it is worth noting the extent to which proposals die in committee without so much as a hearing. Of the bills sponsored by women, only 7.7 percent receive any attention in committee at all. This is in contrast to 11.5 percent of men’s sponsored bills receiving action in committee. It is really at the committee stage that the institutional bias leaves its mark. Moreover, this bias alters the mix of bills moving forward. For women sponsors (on the left), the share of women’s issue bills remaining alive is slightly more than one-third, a drop of 12 percent in terms of their overall portfolio. So, not only do the proposals of women generally fall by the wayside at a greater rate than those of men, but their women’s issues proposals suffer an even greater reduction. A similar (although less pronounced) pattern emerges for men’s portfolios, with women’s issues diminishing at the committee stage.

In the subsequent stages to becoming law, about three-fourths of the remaining bills fall by the wayside. Yet, the proportional mix of bills remains about the same. In terms of laws produced, illustrated in the bottom set of pie charts, women’s issues make up 35 percent of the average woman’s portfolio, compared with 28 percent of the average man’s portfolio. This slightly larger share of women’s issues sponsored by women is more than offset by the smaller number of laws produced by the average woman (about 0.2 per woman per Congress, compared with 0.4 per man).

Multivariate Analysis of the Fate of Women’s Issues

Thus far, we have demonstrated that female legislators specialize in sponsoring particular types of bills, and that they experience systematically less success on these issues in committees and in lawmaking more generally. At face value, these findings fail to support the Expertise and Lawmaking Success Hypothesis, while supporting the Institutional Bias Hypothesis. However, it is plausible that these aggregate findings are merely artifacts of female legislators not having obtained positions of influence in Congress, given that they are relatively junior and hold few committee chairs. Across the 30 years that we study, women averaged 4.1 terms of prior service, compared with 5.4 terms for men; and while 9.2 percent of men in the majority party served as committee chairs and 43.1 percent served as subcommittee chairs across the Congresses in our data set, only 2.9 and 33.7 percent of women in the majority party held either a committee or subcommittee chair.Footnote 20 In light of these disparities, it is important to explore whether our findings are robust to controlling for a legislator’s seniority, committee chair status, and other determinants of legislative success.

To address these issues, Table 2 presents the results from a series of logit regressions with robust standard errors (clustered by legislator), where the unit of analysis is each sponsored bill. The dependent variable takes a value of “1” if a sponsor’s bill was ultimately signed into law (for Models 1–4) or advanced beyond committee (for Model 5), and 0 otherwise. The first three models explore success based on whether the subject of the bill was a women’s issue (Model 1), the bill’s sponsor was female (Model 2), or both, with an interaction variable (Model 3). Models 4 and 5 include these variables, as well as a wide array of other variables that have been demonstrated to be correlated with legislative success in earlier studies (specifically, Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer Reference Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer2013; Volden and Wiseman Reference Volden and Wiseman2014), in addition to a time trend variable (Congress), which serves to control for the underlying propensity for gridlock in recent versus earlier congresses. (This trend variable also serves as a meaningful proxy for the increasing number of women in the House, which has risen over time.) Sources and descriptive statistics for all variables are given in the (Online) Appendix table drawn from data sources including Squire (1992).

Table 2 Determinants of Legislative Success in Congress

Note: Results from logit regressions, with clustered standard errors (by legislator) in parentheses.

*p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01 (two-tailed).

In considering the first three models, several findings clearly emerge. First, consistent with our earlier analysis, women’s issue bills are less likely to be signed into law than are other bills (Model 1). Second, bills sponsored by women are also less likely to be signed into law than are those sponsored by men (Model 2). While the former finding is robust to the inclusion of an interaction term between Women’s Issue and Female (Model 3), the direct effect of a female sponsor on a bill’s fate is now reduced considerably. The interaction variable itself is negative and statistically significant. Put simply, women’s issues bills are significantly less likely to be signed into law than other bills, and female legislators who sponsor women’s issue bills are also less likely to see those bills advanced into law than other bills that they sponsor. In terms of magnitude of these effects, the results of Model 3 show the baseline probability of any bill being signed into law to be approximately 4.1 percent, while bills dealing with women’s issues are half as likely to be signed into law. Moreover, if a female legislator is sponsoring a women’s issue bill, her probability of success drops to a mere 1.3 percent.

Models 4 and 5 demonstrate that these results are substantively robust to the inclusion of a wide array of control variables. As one might expect, bills sponsored by committee chairs, subcommittee chairs, and more-senior members are more likely to advance out of committee (Model 5); and similar factors are positively correlated with whether a bill is signed into law (Model 4). Moreover, after accounting for whether a sponsor holds a committee or subcommittee chair, and for the other control variables, female lawmakers are no less successful at seeing their sponsored bills signed into law than men—unless they are advocating women’s issues.

These results are robust to numerous alternative specifications.Footnote 21 Perhaps most importantly, one may be concerned that these findings are driven by the large numbers of minority party women in recently highly polarized Republican Congresses. If, as suggested by Frederick (Reference Frederick2009) and others, this increase in polarization has corresponded with a decrease in the number of moderate Republican women, one wonders whether ideological shifts among female legislators correspond with changes in the types of policies that women advocate, or whether they continue to advocate for policies that are traditionally associated with women’s issues, as Schultze (Reference Schultze2013) suggests. Moreover, are some women’s issue policy areas, themselves, more polarizing or divisive, perhaps accounting for some of their reduced success rates? Such a combination of circumstances might together explain the results uncovered here. Yet, replicating Model 4 solely on Congresses before the 1994 Republican Revolution shows nearly identical coefficients for Women’s Issue (−0.723) and Women’s Issue×Female (−0.487). Likewise, if we replicate the analysis in Model 4 solely on the 104th–113th Congresses (1995–2014), we obtain substantively similar results with coefficients for Women’s Issue being (−0.901) and Women’s Issue×Female being (−0.363).Footnote 22

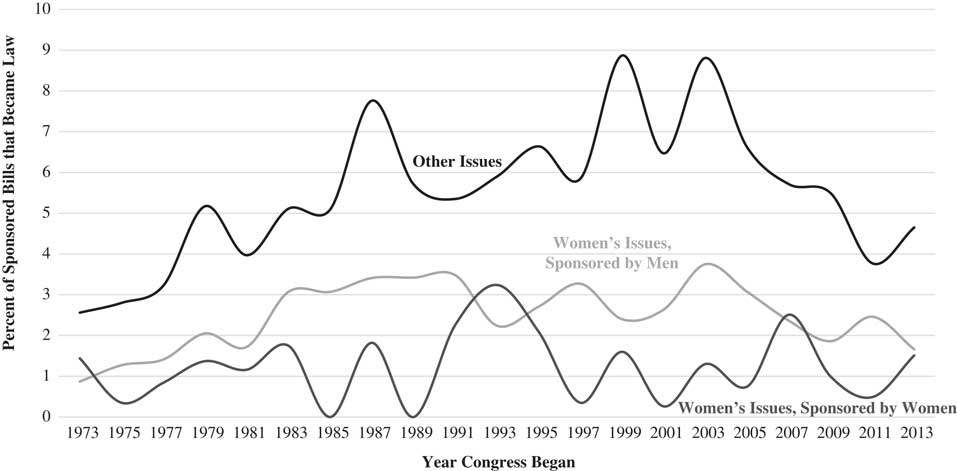

More generally considered, Figure 3 presents bill success rates over time, by issue type and the gender of sponsor. As is illustrated in the Figure, the success rates for “Other Issues” are consistently higher than those for women’s issues. Likewise, the success rates for bills that engage women’s issues are almost always higher when they are sponsored by male legislators rather than female legislators—even in more recent, and politically polarized, Congresses.Footnote 23 Indeed, of the 21 Congresses examined here, only three offer exceptions to this rule, and they are scattered across history—the 93rd (1973–1974), 103rd (1993–1994), and 110th (2007–2008) Congresses. Although these three were all Congresses controlled by Democrats, so too were the two in which not a single women’s issue bill sponsored by a woman became law—the 99th (1985–1986) and 101st (1989–1990) Congresses.

Fig. 3 Percent bill success over time, by issue type and gender of sponsor

In sum, consistent with our earlier aggregate findings, much of the reduced success of women’s issue bills, and of bills sponsored by women more generally, can be traced to committee decisions. On average, 12 percent of “Other Issue” bills reach the floor of the House. In contrast, upon setting control variables at their means, the results of Model 5 establish that women’s issue bills sponsored by men overcome committee hurdles 8 percent of the time. Finally, women’s issue bills sponsored by women average less than 5 percent success through committee. These findings complement recent works on the effectiveness of women in Congress, such as Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer (Reference Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer2013) who trace women’s effectiveness to female lawmakers introducing more bills and building coalitions beyond committee, rather than to success within committees. These results lend further support for the Institutional Bias Hypothesis over the Expertise and Lawmaking Success Hypothesis.

Implications and Conclusion

As the composition of the US Congress has changed to include more women over the past 40 years, significant attention has turned to the differences that these women make in the lawmaking process. Among the most prominent strands of scholarship in this area is work that explores whether women specialize in policy areas often denoted as women’s issues. Drawing on all 151,824 public bills that male and female lawmakers sponsored in the US House between 1973 and 2014, our study illustrates a new, data-driven method that scholars might employ to identify which issues might be most accurately characterized to be “women’s issues.” Employing our method, we have demonstrated that women clearly engage in legislative specialization—often in policy areas that are traditionally regarded as women’s issues. Furthermore, we have also demonstrated that these areas of issue specialization apply to all female legislators, not just legislators of one political party (e.g., Democratic women). Hence, we have identified specialization patterns that are pervasive across female lawmakers, yet transcend traditional political and/or ideological divisions in the US Congress.

Having established these specialization patterns, however, we have also identified that women do not seem to benefit from such specialization efforts. The proposals of women in general (and for women’s issues specifically) are systematically dismissed and disregarded throughout the legislative process, relative to those of men. The explorations here were based on correlative evidence and are thus not assumed to be causal. However, by controlling for many of the partisan and institutional considerations that might explain bill success, we are left with strong evidence that women sponsor bills on different issues than men and achieve less success on those women’s issues. While these findings are compelling in their own right, they also raise several important questions for understanding the future of women’s issues in Congress.

First, how might our findings change as more women are elected to Congress? This question is especially relevant in light of the literature on the “critical mass” of women in legislatures, which speaks to how the percentage of women in a legislature affects political behavior and policy outputs (e.g., Kanter Reference Kanter1977; Saint-Germain Reference Saint-Germain1989; Thomas Reference Thomas1991; Thomas Reference Thomas1994; Ford and Dolan Reference Ford and Dolan1995; Murphy Reference Murphy1997; Bratton Reference Bratton2002; Bratton Reference Bratton2005). Taken together, this work suggests that increasing gender diversity within a legislature may lead to increased attention to, and successful passage of, women’s issue bills (but see Yoder Reference Yoder1991; Kathlene Reference Kathlene1994; Reingold Reference Reingold2000; Cowell-Meyers and Langbein Reference Cowell-Meyers and Langbein2009; Kanthak and Krause Reference Kanthak and Krause2013 for complexities of this relationship). Our over-time analysis suggests that little has changed in the US Congress, however; perhaps women have yet to achieve a critical mass.

Second, in light of the observed difficulties that female legislators experience in committee, in comparison with their male peers, greater attention should be given to intra-committee politics and deliberations, in order to identify the determinants of legislative success in committee.Footnote 24 That gender differences in committee decisions still exist upon controlling for legislator seniority, holding a committee chair, and other institutional variables makes this question particularly intriguing, and worthy of further study.Footnote 25 Also of interest is whether women, in attempting to take on a larger legislative portfolio in order to represent women generally, sponsor more bills that are referred to committees other than the ones on which they sit. Such a possibility may help explain their lack of success within committees.Footnote 26

Finally, one wonders whether similar results might be obtained if our approach were applied to other legislative institutions. Is it generally the case that female legislators specialize in a particular subset of issues, and that those issues tend to be among the most gridlocked? And how might these relationships be exacerbated or ameliorated over time, perhaps due to an increasing number of women in legislatures? Given the growing scholarship on women in US state legislatures, in the US Senate, and in legislative institutions around the world, such questions are ripe for further empirical investigation.