1. Introduction

Populism has been the subject of ever-increasing levels of attention in recent years, as shown by the exponential increase of scholarly articles on the subject. Although political scientists have long lamented the lack of conceptual clarity and consensus on what the term populism denotes, recently some agreement appears to be emerging. Most scholars defer to Mudde's (Reference Mudde2004: 543) definition of populism “as an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite,’ and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.” Even scholars who deviate from Mudde's definition tend to agree that populism itself comes without any fixed programmatic orientation (Stavrakakis et al., Reference Stavrakakis, Katsambekis, Kioupkiolis, Nikisianis and Siomos2017).

Due to the “thin” nature of populism, it is able to shapeshift depending on “what it travels with” (Rovira Kaltwasser et al., Reference Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo, Ostiguy, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017b: 17). We argue that this trait significantly impacts the study of populism as it causes an all too common conflation with the accompanying “host” ideology. Art (Reference Art2020: 10) even concludes his essay on the “analytical utility of populism” stating he is “not convinced that ‘populism’ really exists in the same way (…) that regime types do (democracy, authoritarianism, and now competitive authoritarianism) or that nativism does.” Taking a less drastic stance, several scholars (Rovira Kaltwasser et al., Reference Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo, Ostiguy, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017b: 17; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2018: 4; Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2019: 365–7) have campaigned for greater attention to the distinction between populism and its host ideologies. We take up this mantle and, through analyses of peer-reviewed academic articles, present evidence for several divides running through the field of populism research. These divides not only stem from different host ideologies, but are also rooted in researchers' different methodological approaches and geographical foci.

In order to traverse these divides, we carry out a systematic review using text-as-data and qualitative methods. We do not present a synthesis of previous studies' substantive findings (see e.g., Gidron and Bonikowski, Reference Gidron and Bonikowski2013; Rovira Kaltwasser et al., Reference Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo, Ostiguy, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017a), but rather conduct a meta-analysis focusing on the set-up of previous research on populism. Our unit of analysis comprises 2794 abstracts of English-language journal articles published between 2004 and 2019, across all disciplines. First, we give a broad overview of developments in populism research regarding the quantity of research output and disciplinary diversity. Second, through the analysis of 884 abstracts of political science articles on populism, we reveal how divided the discipline's scholarship is in terms of methodological, theoretical, and substantive focus. Third, we move to an in-depth hand-coded analysis of 50 randomly selected articles in order to assess whether populism is conflated with its host ideologies across the divided field. Our study provides empirical support for several points of criticism: the ad-hoc conceptualization of populism based on single cases or host ideologies, the need for comparative research across regions and host ideologies, and the lack of fruitful exchanges and stimulation between research with different regional foci.

Although systematic literature reviews have received little attention within the social sciences (with an exception: Schwemmer and Wieczorek, Reference Schwemmer and Wieczorek2020), our study shows how they can help political scientists identify flaws and trends in exceptionally productive fields of study. Furthermore, the particularly insightful quality of text-as-data approaches for systematic reviews are demonstrated in their ability to detect patterns, differences, and commonalities in large sets of texts, for example, abstracts of peer-reviewed papers.

2. The divided populism research field

In the wake of Trump's election to the White House and Britain's vote to leave the European Union, attention to populism has skyrocketed. The Cambridge Dictionary declared populism 2017's Word of the Year, as media outlets drastically intensified their reporting, and occurrences of “populism” and “populist” in the New York Times nearly quadrupled from 2015 to 2017 (Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2019: 362). This trend is mirrored in academia: research on populism is trendy and increasingly employed across various disciplines.

Although this development has resulted in important innovations and scientific insights, we lack a systematic overview of this vast field. In this paper, we first show the increase in populism research across different disciplines. Second, we analyze how the field has developed over the last 15 years. We argue that there are divides running through the study of populism and that academics often sit at “separate tables”—following Almond's (Reference Almond1988) famous analogy. Such divisions come with several negative externalities for progress and innovation in academic research. As Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2018: 20) point out: “many of those who are starting to undertake comparative research on populism overlook an important wealth of knowledge that they could, and should, build on.” Although their argumentation calls for “standing on the shoulders of giants”—that is, referring to previous research—we aim to show parallel trends in populism research, that mostly develop separately from each other. In the following section, we discuss three origins of these divides (see Rovira Kaltwasser et al., Reference Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo, Ostiguy, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017b; De Cleen et al., Reference De Cleen, Glynos and Mondon2018; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2018; Urbinati, Reference Urbinati2019). We claim that (1) the geographical variance in the empirical manifestations of populism, and (2) the host ideologies of these examples of populism, as well as (3) the methodological discrepancies, have all led to a divided research field. We argue that this divide drives an overstatement of populism at the expense of the host ideologies in the interpretation of research findings.

As Sartori (Reference Sartori1970) famously argued, the enterprise of comparative politics depends upon the formation of clearly defined concepts and is threatened by “conceptual stretching.”Footnote 1 The particular elusiveness of the concept of populism has been pointed out repeatedly (Ionescu and Gellner, Reference Ionescu and Gellner1969; Canovan, Reference Canovan1981), and was described by Taggart (Reference Taggart2000) as “an essential impalpability, an awkward conceptual slipperiness.” However, recent scholarship does increasingly agree upon an ideational understanding of populism (Aslanidis, Reference Aslanidis2016: 89; Hawkins and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Hawkins and Kaltwasser2017: 527; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2018: 2–3; Bonikowski et al., Reference Bonikowski, Halikiopoulou, Kaufmann and Rooduijn2019: 62; Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2019: 363). Mudde's (Reference Mudde2004) definition has made a particularly profound contribution to unifying the field. Even though scholars might deviate from Mudde's understanding of populism as a “thin” ideology—perceiving populism as “framing device” (Bonikowski et al., Reference Bonikowski, Halikiopoulou, Kaufmann and Rooduijn2019: 62), “discursive frame” (Aslanidis, Reference Aslanidis2016: 98), “communication style” (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2017), “communication phenomenon” (de Vreese et al., Reference de Vreese, Esser, Aalberg, Reinemann and Stanyer2018), or “worldview” (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2009)—most are ideational and agree on the same core features. Other competing conceptualizations consider populism as a strategy (Weyland, Reference Weyland2001), an organizational form (Roberts, Reference Roberts2006), or a cultural style (Ostiguy, Reference Ostiguy, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017).

Academics' methodological choices represent one possible divide in the research field. For researchers who conceive of populism as combined with host ideologies and of a more discursive quality, attempts to measure populism have become a broad literature strand, either using hand-coding (Jagers and Walgrave, Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007), holistic grading (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2009), discourse theories (De Cleen et al., Reference De Cleen, Moffitt, Panayotu and Stavrakakis2019), or automated methods (Rooduijn and Pauwels, Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011). Closely related to measuring populism is the debate about its “degreeism” (Rooduijn and Akkerman, Reference Rooduijn and Akkerman2017; see also Aslanidis, Reference Aslanidis2016). This notion implies that we should use “populist” as a gradual adjective (Cammack, Reference Cammack2000: 155). Contrary to a degree-ist understanding, populist parties are also considered a party family, with a more static understanding of populism employed (e.g., Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013; for a discussion see Aslanidis, Reference Aslanidis2016, 92). The degree-ist versus static understanding of populism is expected to be reflected in different methodological approaches, for instance, qualitative versus quantitative studies. This divide is ubiquitous in political science, beyond studies of populism (Mahoney and Goertz, Reference Mahoney and Goertz2006). Nevertheless, whether research uses quantitative or qualitative approaches, and aims for measurement or categorization, clear definitions of concepts remain fundamental (Sartori, Reference Sartori1970: 1038).

Although populism has become a global phenomenon, its empirical manifestations in different regions are ideologically diverse, with profound consequences for scholarship. Since the 1990s, research on populism in Latin America and Europe has grown at an especially fast pace. In Latin America, a succession of new populist leaders of various ideological sub-types emerged in the early 1990s and around the turn of the millennium (De la Torre, Reference De la Torre, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017). Archetypal examples include the neoliberal Fujimori in Peru during the 1990s, and socialist Chavez in the following decade in Venezuela. Tensions between the inclusionary promises of populists and the harm done to liberal democratic institutions once in power have shaped debates in the literature (Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Rovira Kaltwasser2012; Levitsky and Loxton, Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013).

In Europe, the electoral success of populist radical right parties in the early 1990s, for example, the FN, the FPÖ, and the SVP, sparked academic interest into the determinants of this breakthrough (Taggart, Reference Taggart1995; McGann and Kitschelt, Reference McGann and Kitschelt2005; Norris, Reference Norris2005; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). In the subsequent one and a half decades, scholarship on populism in Europe continued to focus overwhelmingly on right-wing populist parties.

Even though left-wing populism has become increasingly relevant in Europe, especially in the south, we argue that the geographical divide in populism research is mostly rooted in the different host ideologies that are prevalent on the two continents. Several authors have warned about the risk of conflating populism with its host ideologies. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2018: 4) point out that “we need to study populism not in isolation but rather in combination with different ideologies.” De Cleen and Stavrakakis (Reference De Cleen and Stavrakakis2017) argue that distinguishing between populism and nationalism is necessary in order to grasp the complexity and variance of different populist actors. Rooduijn (Reference Rooduijn2019: 365–7) emphasizes that we must not draw generalizations from findings on—for instance—right-wing populist voters to the “broader category of ‘populists in general’.” Populism is often used as the central explanatory concept for outcomes that are more related to the host ideology, for instance contagion effects on mainstream parties' immigration positions. Comparing cases of populism in different regions and ideological forms, would allow researchers to draw more reliable and generalizable conclusions (see also Rovira Kaltwasser et al., Reference Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo, Ostiguy, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017b: 17–8).

Building on the pleas voiced by leading scholars, we claim that these imprecisions in the study of populism are rooted in three intertwined divides: first, the geographical variance in the empirical manifestations of populism, second, the conflation of populism with its host ideologies, and third, methodological discrepancies. Geography and ideology are two divides that are linked due to the regional clustering of populist actors of similar ideologies. Methodology is linked to geography and host ideology as the leading scholars who shaped the sub-fields paved the way for very different methodological traditions. For instance, the late Laclau (Reference Laclau1978, Reference Laclau2005), whose work builds on a Gramscian and psychoanalytical tradition which rejects quantitative approaches, has been very influential for Latin American research on populism.

3. Systematic reviews in political science

Although scholars of political science use literature reviews or meta-analyses to compare studies' findings, systematic reviews of research trends have hardly been employed in the discipline (Dacombe, Reference Dacombe2018: 148). They differ from classical literature reviews as “they conform to the methodological standards used in primary research, namely transparency, rigor, comprehensiveness, and reproducibility” (Reference Daigneault, Jacob and OuimetDaigneault et al., 2014: 268). Using existing studies as the unit of analysis (Petticrew and Roberts, Reference Petticrew and Roberts2006), this specific methodology “locates existing studies, selects and evaluates contributions, analyses and synthesizes data, and reports the evidence in such a way that allows reasonably clear conclusions to be reached about what is and is not known” (Denyer and Tranfield, Reference Denyer, Tranfield, Buchanan and Bryman2009: 672).

Dacombe (Reference Dacombe2018, 154–5) argues that systematic reviews can be particularly helpful to political science for scoping, problem formation, and as meta-analysis of existing findings. They can help researchers to locate flaws and gaps in the literature, and to detect where conflicting findings point toward a more complex picture than previously assumed. Although most systematic reviews study outcomes and different sets of explanatory variables, our paper instead studies an earlier stage of the research cycle: the existing studies' research design and research objects. A transparent and systematic synthesis of the conceptualization and set-up of studies in the field can provide valuable insights into the strengths and weaknesses of the abundant existing scholarship.

4. Data collection and methods

Collecting data for a systematic review is—like for any other type of research—no trivial matter. Petticrew and Roberts (Reference Petticrew and Roberts2006: 81–5) discuss two mutually exclusive characteristics of the search strategy: sensitivity and specificity. Although a high sensitivity finds all relevant studies, a high specificity comes with a greater accuracy, that is, only relevant studies will be identified, keeping the number of false positives low.

As we are interested in studies on populism across disciplines as well as in political science specifically, we start with a broader data collection approach before narrowing it down to the discipline of interest. Our data consist of abstracts of peer-reviewed journal articles which were downloaded from Web of Science (WoS) (Serôdio, Reference Serôdio2018). We analyze abstracts instead of full papers, first, due to data availability; most articles are behind paywalls whereas abstracts are freely available. Second, abstracts summarize the key aims, methods, and findings of articles (Syed and Spruit, Reference Syed and Spruit2017; Hofstra et al., Reference Hofstra, Kulkarni, Munoz-Najar Galvez, He, Jurafsky and McFarland2020). Web of Science has several advantages regarding accessibility, selectivity, and coverage. It covers more than 18,000 journals, with far less “gray” literature than Google Scholar, and allows for flexible search queries. Our search was limited to only include: (1) English-language publications,Footnote 2 (2) articles as document type, (3) journals that are included in at least one of the following indexes: Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts & Humanities Citation Index, and Emerging Sources Citation Index. Moreover, we limited the time period to 2004–2018, as Mudde's seminal definition was first published in 2004 and populism research has been growing at the fastest pace after this point (see figure 1 in the online appendix). WoS offers a basic topic search that covers title, abstract, and keywords of the article. For our search, we specified “populis*” which picks up “populist,” “populists,” and “populism,” with the asterisk serving as a wild card. After removing duplicates, our full data set comprises 2794 journal articles from various disciplines. The data include the title, journal, abstract, keywords, publication date, author(s) and affiliations, grant number and funding text, doi, and the WoS category (i.e., discipline) for each article.Footnote 3

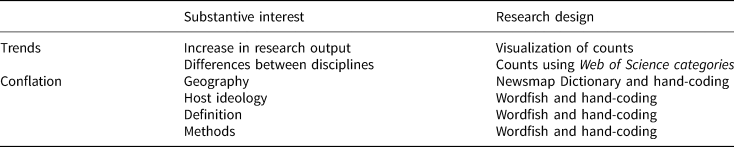

We employ a multi-step research design (Table 1) to analyze these data and test our theoretical expectations. First, we study the expansion of populism research across disciplines using the counts of published papers. Second, we show the geographical foci of studies, using the newsmap dictionary. Third, our Wordfish model—implemented with quanteda (Benoit et al., Reference Benoit, Watanabe, Wang, Nulty, Obeng, Müller and Matsuo2018)—shows how the research field is divided by different geographical foci, methods, and host ideologies. This conflation is then systematically assessed by hand-coding a random sample of 50 full articles. We demonstrate in detail whether studies clearly define populism, its relevance to the argument of the paper, whether they avoid the conflation with other ideologies, and whether these ideologies are considered separately and/or in interaction with populism.

Table 1. Methods for different trends and possible divides

5. Empirical results

5.1 The surge of populism research

First, we consider the broader developments in populism research. We compare the research output across disciplines using the categories that each item in the WoS-core collection is assigned to. We use this classification to show trends in the general and discipline-specific attention toward populism. Table 2 shows the total number of articles by disciplines from 2004 to 2018, excluding disciplines with less than 20 publications on populism.Footnote 4 Political science is by far the front-runner with 884 articles published on populism, followed by sociology, communication studies, area studies, and history.

Table 2. Total number of published journal articles by disciplines

Figure 1 shows the nominal development of publications over time. We focus on political science as our main discipline under review, as well as several neighboring disciplines which account for most publications. All other disciplines are subsumed under the category “Other.” Both political science and the “Other”-category show a steady growth. The trend for political science takes off in 2012. For sociology, communication studies, international relations, area studies, and economics the numbers are comparatively low and stable over the years, until a sharp increase in 2016, which seems to confirm the interpretation of Rovira Kaltwasser et al. (Reference Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo, Ostiguy, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017b: 11), that the 2016 US presidential election was a turning point that greatly motivated US scholars to study the concept of populism.

Figure 1. Yearly number of published journal articles on populism across disciplines.

In the subsequent sections of the analysis, we limit our data to political science articles. First, we study how the focus on different world regions is distributed across the research field using the newsmap dictionary developed by Watanabe (Reference Watanabe2018). This dictionary is structured into three different levels: the country-level, regions within continents (e.g., North America and South-East Asia), and continents. At the lowest level, each country-specific dictionary comes with several keywords, for example, uk, united kingdom, britain, british, briton*, brit*, london for Great Britain. The country dictionaries are clustered into regions and then continents by aggregating the hits for each country. We also added keywords such as “*europe*” and “latin america*” to the dictionaries. This multi-level design allows us to categorize the abstracts by regions. As we include abstracts falling into several categories, graph 2 includes 1079 geographical references while our sample includes only 884 papers.

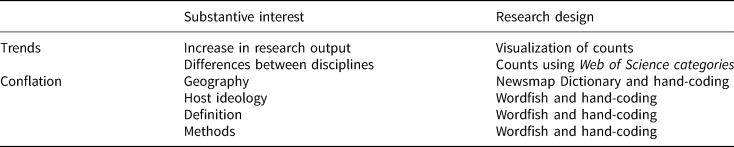

The information on regions is missing for 237 abstracts, which is shown by the category “no information” in Graph 2. More interesting, however, is how much Europe sticks out.Footnote 5 The region receives by far the most attention from researchers, at least six times more than North America, Latin America, Africa, Asia, and Oceania (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Yearly number of published journal articles on populism by regional focus.

5.2 The unidimensional divide: different regions, methods, and host ideologies

In this section, we aim to show how methods, regions, and host ideologies divide the field of populism research. We do so by using Wordfish, a text analysis model which was developed to scale large amounts of text based on a latent dimension in an unsupervised manner (Slapin and Proksch, Reference Slapin and Proksch2008; see also Grimmer and Stewart, Reference Grimmer and Stewart2013). It is often used to estimate the position of political speeches on a left-right ideological space. In scaling the texts, Wordfish assumes that some words are more common on one side of the spectrum (e.g., left-wing politics) than on the other. We use the Wordfish algorithm in order to show how much abstracts differ from each other and which words are indicative for a position on the extremes of the spectrum. As the model is unsupervised, it picks up the least latent dimension present in the texts. The researcher employing the model has no control over what this dimension is but can interpret this dimension after applying the model by evaluating the words that “load” most heavily on this dimension.

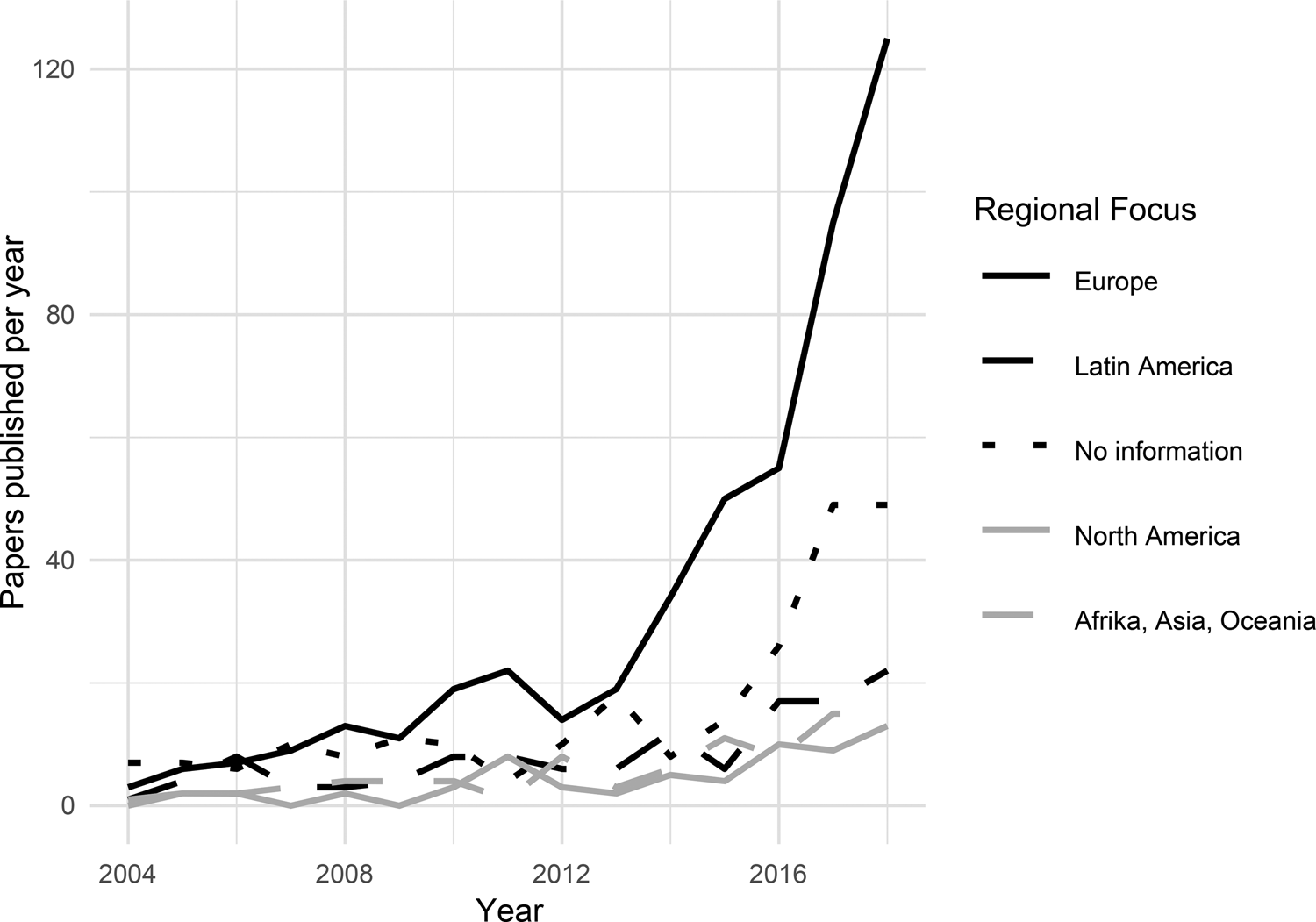

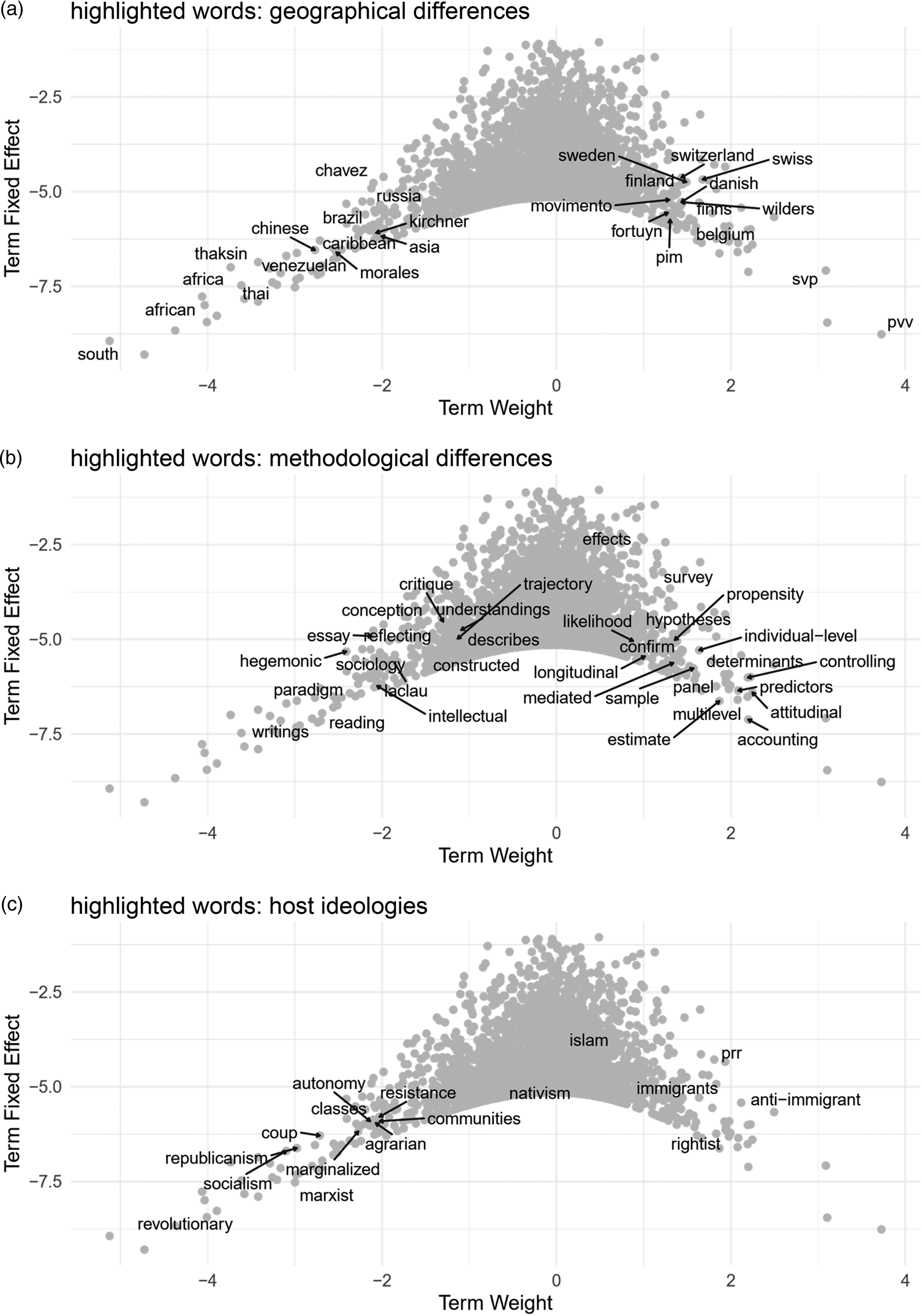

Figure 3 shows results of the Wordfish model applied to the abstracts of the 884 political science papers on populism published from 2004 to 2018. The three panels in the figure contain the distribution of the “features”, that is, the words in the abstracts, where the x-axis shows the relevance of single words for the underlying dimension and the y-axis shows term fixed effects. In short, higher term fixed effects show that a word is used more frequently in the abstracts, whereas more extreme values on the x-axis signal an asymmetry in the use across the spectrum of the underlying dimension which the model identifies. Here, the graph has the typical shape of Wordfish models where more common words that are in all abstracts are also less indicative for the position of a text on the dimension.Footnote 6 The location of a word on the x-axis provides an indication of its location along the dimension identified by the Wordfish algorithm. By considering how words representative of the proposed divisions are distributed on the x-axis, we can also assess whether these division align on one dimension or are cross-cutting.

Figure 3. Wordfish features plotted by weight and frequency.

Although panels a–c show the exact same underlying model, we highlight different features in each panel that represent the three proposed divisions. These words were identified through a close reading of the features (see table 3, online appendix) and are related to the divides which separate the field of populism research. In panel a, the highlighted words on both ends of the spectrum—the latent dimension that the Wordfish models measures—are related to geography. The words on the right-hand side relate to European countries and parties, while the words on the left refer to the Global South. In panel b, the words are indicative of a methodological divide. The words on the left-hand side are related to qualitative, constructivist research, while the words on the right-hand side point in the direction of quantitative research, with words such as “determinants,” “controlling,” and “estimate.” Finally, panel c shows words related to host ideologies. Although on the left we find words like “revolutionary,” “Marxists,” “socialism,” or “classes” that suggest a left-wing ideology, the highlighted features on the right suggest a radical right host ideology, for example “immigrants” and “anti-immigrants.”

These findings indicate that the field of populism research is indeed clearly split into two different traditions, and this divide stems from different, but interrelated factors: differences in host ideologies, geographical focus, and methodological approaches.Footnote 7 Although the graph above only shows us the features, that is, the words, we argue that the clustered location of features related to methods, geography, and host ideology points to the existence of two camps in the field of populism research. In the following section, our hand-coded analysis of a sample of these papers shows that this divide may be traced back to an overstatement of populism at the expense of host ideologies. As we have already argued, the regional clustering of populists sharing the same host ideologies, and regional-specific traditions of populism research, drive this conflation of host ideology and populism.

5.3 The latent conflation of populism and host ideologies

The preceding Wordfish model reveals what researchers claim to study; that is, how they frame their papers in their abstracts. What is the relationship between populism and host ideology within the papers themselves? In this section, we study whether the theoretical mechanisms employed are in fact based on populism or if they are rather rooted in its host ideology due to a conflation between the two. We hand-code a random sample of 50 full articles out of our population of 884 populism abstracts.Footnote 8 We select the articles at random, in order to avoid the introduction of bias as other selection criteria would. For example, to instead select by journal impact factor would likely favor quantitative and/or European-focused studies. Comprehensiveness across both sides of the divided field—in terms of host ideologies, geographical focus, and methods—is of course crucial to our analysis. Moreover, our findings indicate no relationship between the journal impact factor and an article's effective conceptualization of populism.Footnote 9

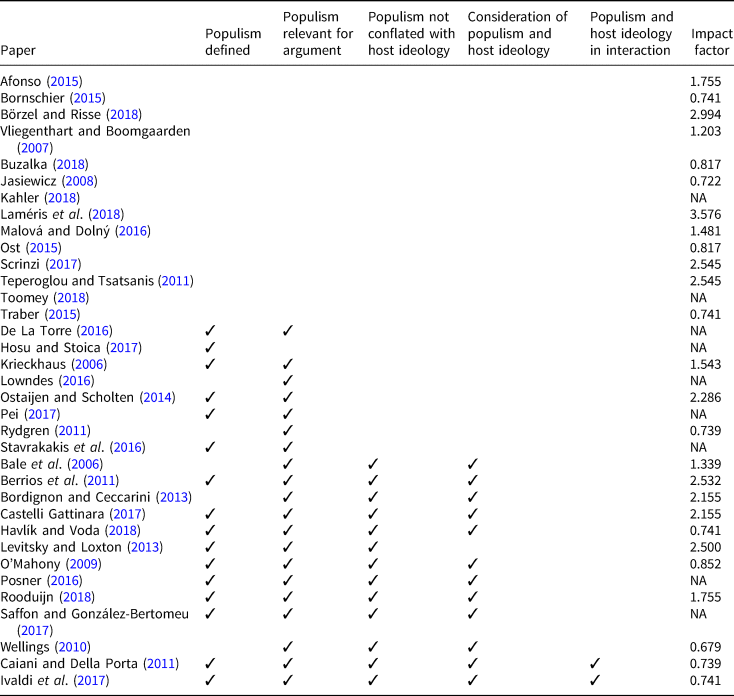

As depicted in Table 3, we present the hand-coded papers following several criteria, to systematically assess the papers' (mis)use of the concept of populism. Each paragraph of the section corresponds to an indicator used in the coding process and presents details on the papers and how we coded them. First, we assess whether they provide a clear definition of the concept of populism. Second, we check whether populism is relevant for the argument of the paper, rather than, for instance, merely being used as a label. Third, we ask whether populism is used in a way that does not conflate its features with the host ideology's features, either left- or right-wing. In other words, do scholars argue that populism is driving their hypotheses, while the host ideology is in fact the determining characteristic? Fourth, whether a paper considers both populism and host ideologies separately and fifth, most sophisticated of all, whether it considers the concepts in interaction with each other. In our opinion, those papers that do not fulfill any of the criteria would have been just as successful without employing the populist concept. The next section presents the results of our hand-coding approach, consecutively following the individual indicators.

Table 3. Categorization of hand-coded papers

Our findings show that the distribution of these indicators is not at random, but seem to follow each other sequentially. That is, in papers which do not define populism, the concept is very likely to be irrelevant to the theoretical argument; if the concept is irrelevant for the study, then it also tends to be conflated with the host ideology.

Our analysis reveals, first, the prevalence of the use of populism purely as a label. In such papers, the focus is upon so-called “populist parties” (of various forms), yet populism is often left undefined. Of the papers coded, only 16 provide a definition of populism, of which six use an ideational understanding, five consider populism a strategy, one considers it a frame, one as an economic policy approach, and five have a discursive understanding of the concept.

Second, in the papers lacking a definition of populism, the very concept is often irrelevant to the argument or causal claim made. The populist label is attached to research that speaks rather of other ideological concepts. Kahler (Reference Kahler2018) discusses the dangers of “emerging populist groups” such as “supporters of Trump, the UK Independence Party (UKIP), or […] the National Front” for global governance due to their anti-globalization stances. Yet, such stances are unrelated to populism, and rather rooted in radical-right and radical-left ideologies. Similarly, the research of Toomey (Reference Toomey2018) into Orban's election victories posits the importance of a “populist-urbanist cleavage” that helped to legitimate Orban's reactionary image of Hungarian nationalism.Footnote 10 Buzalka (Reference Buzalka2018) also leaves populism undefined but it seems to be an irrelevant concept for the argument that concerns a strategy of peasant mobilization based upon communist nostalgia. More commonly, research on the European radical right subsumes this party family as “populist,” which is then applied unhelpfully as the primary label with which these parties are categorized. For instance, Afonso (Reference Afonso2015) and Vliegenthart and Boomgaarden (Reference Vliegenthart and Boomgaarden2007) study populist radical right parties, to which they repeatedly refer as “populist right-wing” and “anti-immigrant populist” parties. Similarly, in studies of the “right-wing populist” SVP by Traber (Reference Traber2015), the “populist radical right” Lega Nord by Scrinzi (Reference Scrinzi2017), the “rightwing populist” LAOS by Teperoglou and Tsatsanis (Reference Teperoglou and Tsatsanis2011), the “radical populists” SRP by Jasiewicz (Reference Jasiewicz2008), and the Polish “illiberal populist nationalism” by Ost (Reference Ost2015) the concept plays no analytical role. Despite the use of the populism label, the mechanisms in these papers are unrelated to the presumed populist nature of the parties and so the concept remains a buzzword.

Third, we find that a conflation of populism with nativism is a common feature of European populism research. That is, theoretical arguments are connected to the concept of populism and hence presented as central to the study, while the host ideology is in fact the factor driving the core arguments. Börzel and Risse (Reference Börzel and Risse2018) deem “populist parties” culpable for the stalemate in the Schengen crisis, due to their mobilization on nationalist and anti-migrant attitudes, and Bornschier (Reference Bornschier2015) refers to the (extreme) populist right who represent the polar opposite of the New Left on the cultural dimension. Clearly, “nationalist,” “anti-migrant,” or simply “radical right,” parties would be a more appropriate label in such cases. Laméris et al. (Reference Laméris, Jong-A-Pin and Garretsen2018) develop a typology of voter ideology dimensions along economic and cultural lines: the latter opposing preferences for personal and cultural freedom to “nationalist, protectionist and populist preferences.” This clustering suggests that populism is inherently linked to nationalism and protectionism, rather than a concept that can also be comfortably linked with left-wing (economic and/or cultural) ideas. A similar issue arises in the North American context. Pei (Reference Pei2017) attributes the promotion of white supremacism to the “populist campaign proposals” of Trump, as “with relation to foreigners and to minorities distinct from ‘the people,’ populism emphasizes hostility and exclusion.” In their analysis of policy populism, Ostaijen and Scholten (Reference Ostaijen and Scholten2014: 685) speak of “typically ‘populist’ topics like immigration, integration, justice and crime” and focus upon policies that exclude migrants; and Malová and Dolný (Reference Malová and Dolný2016: 9) refer to a “populist and paternalist political style, [that portrays] refugees and migrants as a security risk.” Although Hosu and Stoica (Reference Hosu and Stoica2017) do well to consider populism as a possible presence on both sides of the political spectrum, the analysis focuses upon right-wing populist parties, which are defined by their nationalist appeals and anti-immigrant rhetoric. Our position is that nativism—and not populism—is in fact the relevant concept to explain the hostile and exclusionary emphasis on foreigners and minorities.

The conflation of populism and host ideology is also apparent on the other side of the divided field. The majority of papers on Latin American populism analyzes (left-wing) populists in government and study the consequences for the national economies and democratic quality (e.g., Berrios et al., Reference Berrios, Marak and Morgenstern2011; Levitsky and Loxton, Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013). Yet, many papers are not clear in the conceptual divide between the thin populism and the left-wing host ideology. When Stavrakakis et al. (Reference Stavrakakis, Kioupkiolis, Katsambekis, Nikisianis and Siomos2016) describe the success of Chavez's “populist politics,” they do not distinguish actions which may well be considered populist—democratization, participatory reform—from left-wing economic policies—wealth redistribution and social welfare programs. Studies from de la Torre (Reference de la Torre2016) and Levitsky and Loxton (Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013) aim to delineate the democratic consequences of populism, yet the distinct contributions of left-wing ideological components are not considered, nor are the crucial differences from non-populist leftists clearly argued. Others focus upon the consequences of left-wing ideology—increased government spending and redistribution—rather than populism itself (Krieckhaus, Reference Krieckhaus2006). A similar approach is shown in the (North American) research of Lowndes (Reference Lowndes2016) on Trump's “White Populism,” defined as the combination of nativism with progressive economic positions. The conclusions of research into Latin American populist governments that conflates populism and leftwing ideology are thus prevented from being applied to cases of populism on the other side of the “divide,” for example, increasingly common examples of European right-wing populism in government.

We do find examples which provide a clear definition of populism, where the concept is relevant to a paper's argument, and populism is considered separately from host ideologies. A consummate example is the study of Posner (Reference Posner2016) which defines populism in a strategic sense following Weyland (Reference Weyland2001), and clearly distinguishes its effects from the regime's left-wing rhetoric. Similarly, Saffon and González-Bertomeu (Reference Saffon and González-Bertomeu2017) consider the democratic consequences of populist governments in isolation from their varied economic orientations, and Berrios et al. (Reference Berrios, Marak and Morgenstern2011), following Roberts (Reference Roberts2006) organizational conceptualization of populism, analyze hydrocarbon nationalization by Latin American leaders and consider the separate effect of left-wing ideology and populism.

Other positive (European focused) examples include: the study of centrist populism in Eastern Europe from Havlík and Voda (Reference Havlík and Voda2018), which test models based upon the theoretical underpinnings of both populist attitudes and center-right ideology; the discursive analysis of three types of far-right actors from Castelli Gattinara (Reference Castelli Gattinara2017) which shows the populist features that differentiate the populist radical right from extreme-right and ultra-religious groups; and the study from O'Mahony (Reference O'Mahony2009) which demonstrates the use of populist rhetoric during the Irish referendum debate from actors across the political spectrum. Focusing instead upon the demand-side, Rooduijn (Reference Rooduijn2018) assesses the importance of populist attitudes toward voting for populist parties of various host ideologies. Although the studies of Wellings (Reference Wellings2010), Bordignon and Ceccarini (Reference Bordignon and Ceccarini2013), and Bale et al. (Reference Bale, Taggart and Webb2006) lack a clear definition of populism, they all consider the distinct contribution made by features of populism that fit with the ideational conceptualization while avoiding conflation with other ideological features.

The most sophisticated studies not only consider populism and other host ideologies separately, but also their interaction with each other. The study of Ivaldi et al. (Reference Ivaldi, Lanzone and Woods2017) is commendable in this regard, due to its consideration of parties from across the left-right spectrum, and the interaction between the core features of populism with their varied “host” ideologies. Caiani and della Porta (Reference Caiani and della Porta2011) reveal the various forms of populism that emerge in different extreme right-wing parties and movements in Italy and Germany. The different discursive opportunity structures provided by organizational and national contexts affect how relevant populism is for the actors and thus the way populism is embodied. Such deep engagement with the interdependence between populism and its host ideologies is rare. The application of the populism concept in this manner would be beneficial for other research foci— across geographical regions, ideological forms and methodological approaches—and facilitate the cross-fertilization of ideas regarding populism across the currently divided field.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we conduct a comprehensive meta-study of populism research. We show that scholars of populism are “sitting at separate tables” due to three divides. These are rooted in (a) the different host ideologies under analysis, (b) different geographical foci, and (c) methodological differences. We show that although many studies use populism as a central theme, the actual focus of this research is the host ideology. Such misuses of the concept, and the divisions running through the field, come with several negative consequences. In particular, they are likely to hinder cross-fertilization between different strands and hence pose an obstacle to generalizable scientific findings regarding populism, distinct from host ideologies.

In our empirical analyses, we show this in two main steps. First, we rely on the abstracts of all 884 political science articles published in peer-reviewed journals from 2004 to 2018 and analyze them using text-as-data approaches. Our Wordfish model shows that all three proposed divides actually exist. Furthermore, they cut through the research field in the same vein; that is, all divides align on one dimension. One pole is typified by a focus on the Global South, a left-wing host ideology and the use of qualitative methods, while a focus on Western countries, a radical-right host ideology and quantitative methods are located on the other side of the spectrum.

In a second step, we complement the quantitative analyses with a more in-depth assessment of the field. We carry out a detailed hand-coding of a random sample of 50 articles. This step goes beyond quantifying the use of populism in the 884 articles and aims to systematically assess the true role that populism, host ideologies, geography, and methods play in these articles. Our results show that populism is often used as a label to describe the party family without being used in the studies' argumentation, and is commonly conflated with other ideologies. We show examples of papers from both sides of the divide that base their theoretical expectations on host ideologies, while claiming that the phenomenon under study is populism. We conclude by highlighting papers that engage with the concept across different ideologies and emphasize the interplay between host ideologies and populism. Our paper contributes to the literature in three ways. First, we offer a comprehensive yet succinct overview of how populism research has developed since 2004 which, due to its considerable growth, would not be feasible with a classical literature review. Second, the use of both text-as-data methods and qualitative hand-coding shows the utility of mixed methods in order to conduct systematic literature reviews of research strands in political science. Although classic literature reviews can describe a few key publications, systematic reviews are better able to analyze the direction of the whole field. Third, we provide evidence for a divided field and demonstrate how a focus on host ideologies comes at the expense of clear findings on populism. The two sides of the field—both of which have a tendency toward this lack of conceptual distinction—develop conceptions of populism that are different from one another due to their different host ideological, geographical, and methodological foci. Thus, to crudely stereotype, in European studies nativism and populism are combined and populism is portrayed fearfully, and in Latin American studies socialism and populism are combined and the latter concept is portrayed more hopefully.

Our findings leave us with three recommendations on how the field of populism research ought to move forward. First, studies should provide a clear definition of populism. Although a Sartorian approach would demand that all scholars adopt the same definition—for example, the dominant ideational understanding of Mudde (Reference Mudde2004)—we make a more modest case for scholars to provide clear definitions, which might well vary. Second, they should be explicit about the contribution of populism to their article's core argument, while keeping the concept separate to other (“host”) ideologies. Third, scholars ought to dedicate attention to the connection between populism and its host ideologies; how do they interact or condition one another? This would better enable the comparative study and formulation of hypotheses regarding populist and non-populist parties with different host ideologies. As Mair (Reference Mair, Della Porta and Keating2008: 196) states, “meanings and applications may vary, but they must be explained and justified. This is where opinion ends and comparative social science begins.” As it stands, too many lessons about populism that are learnt from one side of the field cannot be readily applied to the other. Following the above propositions would help the cross-fertilization of ideas across our currently divided field.

The current hype surrounding the term, and its frequently imprecise application, also have real-world consequences. When the far-right are defined (primarily) as populist, the ideological concepts that are more fundamental to their political programs are concealed (Brown and Mondon, Reference Brown and Mondon2020). The blurring of populism and nativism plays into the hands of populist radical right parties as it enables them to disguise their nativism with populism, and thus supports their claims to be down to earth and close to “the people.” This is especially misleading as “populism comes secondary to nativism, and within contemporary European and US politics, populism functions at best as a fuzzy blanket to camouflage the nastier nativism” (Mudde, Reference Mudde2017). Moreover, the distinctiveness of those labeled as populist on the left and right are obscured by the lack of attention to their differences, rooted in their contrasting host ideologies. The use of populism as a mere “buzzword,” and a pejorative one at that, therefore puts a roadblock in the way of debate regarding political concepts and alternatives to the status quo. It may also provide cover behind which ideas harmful to liberal democracy can hide and develop.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.44

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Andrej Zaslove, Luke March, Heike Klüver, Sarah de Lange, Hanspeter Kriesi, Stefan Müller, Theresa Gessler, Vicente Valentim, Louisa Bayerlein, Anja Neundorf, and two anonymous reviewers for their excellent feedback. We are also grateful to all those who provided comments on earlier versions of the article presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the European Political Science Association, the EUI Workshop “Populism in Europe: A Critical Debate for Interesting Times”, and the Mini Conference of the Summer School for Women in Political Methodology 2020.