With a focus on firms, this paper reconsiders the proposition, implied by various arguments but not yet empirically demonstrated, that there is greater lobbying activity in more democratic regimes. This reconsideration is theoretically important because it helps to develop a political framework with regime type variation for special interest behavior (and not simply for voting), thus helping to explain political system differences on issues such as international trade and currency policy where the democratic state arguably does not face much direct voter pressure. If we can account for such policy differences based on lobbying variation by political regime type, then we have a new way to explain, for example, why more democratic governments have more open trade policies and more flexible exchange rate regimes.

Our analysis begins with a simple state/society political model in the style of Grossman and Helpman (Reference Grossman and Helpman1994). The state sets policy, including but not limited to international trade and currency policy, with some input from society. Societal actors with diverse interests have two possible ways to push the state toward their preferred policy outcome. The first is by voting; individuals can transmit their preferences through an electoral channel where this mechanism exists (i.e., in more democratic regimes). The second is by lobbying; organized groups may be able to influence policy by providing information and making financial contributions to the state. Thus, there is also a special interest channel through which firms may be able to influence state policy in both democratic and autocratic regimes.

When comparing democratic and autocratic regimes, scholars observe many systematic policy differences. Focusing on foreign economic policy, the empirical evidence shows that governments in more democratic regimes tend to hold more open trade policies (e.g., Bliss and Russett, Reference Bliss and Russett1998; Remmer, Reference Remmer1998; Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Milner and Rosendorff2000; Mansfield et al., Reference Mansfield, Milner and Rosendorff2002; Mitra et al., Reference Mitra, Thomakos and Ulubasoglu2002; Milner and Kubota, Reference Milner and Kubota2005; Kono Reference Kono2006; Hollyer and Rosendorff, Reference Hollyer and Rosendorff2012). The empirical evidence also shows that more democratic regimes usually operate with more flexible exchange rate regimes (e.g., Leblang, Reference Leblang1999; Frieden et al., Reference Frieden, Ghezzi, Stein, Frieden and Stein2001; Broz, Reference Broz2002; Bearce and Hallerberg, Reference Bearce and Hallerberg2011; Bearce, Reference Bearce2013; Steinberg and Malhotra, Reference Steinberg and Malhotra2014). In many ways, these represent primary results for Comparative/International Political Economy because they link a fundamental political concept (regime type) to the central phenomenon of economic globalization. However, these results are harder to explain than it may appear.

In trying to explain such policy differences, scholars have tended to rely on arguments about voter pressure (the first influence channel). As Kono (Reference Kono2006, 369) offered on international trade: “Voters as-consumers prefer liberal trade policies that lower prices and raise real incomes.” Consequently, “[c]ompetition for votes should thus drive democratic leaders toward liberal policy positions.” As Bearce and Hallerberg (Reference Bearce and Hallerberg2011, 172) proposed for exchange rates: “Voter/electoral pressure pushes more democratic governments to resolve” the trade-off between exchange rate stability and domestic monetary autonomy with international capital mobility “in favor of domestic monetary autonomy, leading to less de facto exchange rate fixity, because the median voter is likely to be a domestically oriented producer with a preference for this policy outcome.”

However, arguments about voter pressure may not provide much leverage in explaining regime type differences on policies, like those related to international trade and exchange rates, where most citizens do not consider the issues to be politically salient, do not have clear policy preferences, and tend not to cast their vote based on these issues even when they have coherent preferences (e.g., Guisinger, Reference Guisinger2009; Eichenberg, Reference Eichenberg2016; Kleinberg and Fordham, Reference Kleinberg and Fordham2018; Betz and Pond, Reference Betz and Pond2019). Thus, the puzzle remains: how to explain regime type differences on issues such as international trade and currency policy where more democratic states do not face much direct voter pressure?Footnote 1

Perhaps one can account for these differences in terms of lobbying (e.g., Bauerle Danzman, Reference Bauerle Danzman2019), the second influence channel in the simple political model outlined above. However, this would not be possible on a systematic basis if special interest politics operate in more or less the same way across regime types. But if lobbying patterns are generally different in more democratic regimes (e.g., more frequent lobbying with a different set of firm preferences within the special interest channel), then we may have a way to explain why democracies have different policies compared to autocracies on issues such as trade and currency policy where there is little direct electoral pressure on democratic policymakers.

To explore if/how lobbying patterns differ in terms of the political regime, this paper uses data from the World Bank's Enterprise Surveys (WBES), considering almost 29,000 firms across 83 country/year surveys, to test the hypothesis that this political activity should be greater in democracies. Using a variety of democracy indicators and different measures of lobbying, we find strong support for this positive relationship. Having demonstrated that more firms enter the special interest channel in democracies, we then use these data to consider the trade and currency policy preferences of firms within the special interest channel, comparing democracies with non-democracies. Consistent with the evidence that democracies have more open trade policies, our results show a greater percentage of exporting firms with an expected preference for free trade and a lesser percentage of import-competing firms with an expected preference for trade protection within the democratic special interest channel. Also consistent with the existing evidence that democracies operate with more flexible exchange rate regimes, our results show a greater percentage of non-tradable firms with an expected preference for domestic monetary autonomy within the democratic special interest channel.

Before proceeding, it is important to address two concerns that might be raised about this analysis. The first is that a hypothesis about greater lobbying within democracies is simply obvious. We acknowledge that this may well be true for certain readers, but this relationship has not been demonstrated anywhere else in the literature. Indeed, the existing empirical evidence seems to suggest that this relationship is false (i.e., firm lobbying is not greater in more democratic regimes). For example, Weymouth (Reference Weymouth2012, 18) similarly hypothesized a positive relationship between firm lobbying and democracy but reported no support for this proposition when using the WBES dataset, concluding that “democratic political institutions appear to have no effect on lobbying.”

A second concern might be that we analyze WBES data from 2002 to 2005. However, there are no more recent datasets that address important questions about the cross-national variation in lobbying. Indeed, as argued by Kanol (Reference Kanol2015, 110), “there is, so far, scarce” research that compares, especially quantitatively, the lobbying patterns across countries and regions of the globe. Certainly, there are rich new datasets on firm lobbying that have been used to study trade liberalization (e.g., Kim, Reference Kim2017), but they capture this activity within a single country, usually the United States, so they are inappropriate for testing the argument advanced here.

1. The frequency of firm lobbying

1.1 The argument

We argue that firm lobbying should be greater in more democratic political regimes. This argument builds from the understanding that the special interest channel, defined as ways to influence state policy through the provision of money and/or information, is narrower in autocracies, or wider in democracies (Bearce and Velasco-Guachalla, Reference Bearce and Velasco-Guachalla2020). A “wider” special interest channel simply means that more firms and other organized groups can conduct these political activities, although the standard collective action problem is not expected to disappear.

First, a different structure of government should make the special interest channel wider in democracies. Democracies include separate branches, following the principle of checks and balances, with multiple bureaucracies within each branch (e.g., cabinets in the executive branch and committees in the legislative branch). Likewise, democracies often share, or distribute, power among multiple political parties both across branches and within the same branch of government. Such democratic institutions create greater access points for societal interest groups, lowering the costs of lobbying (Ehrlich, Reference Ehrlich2007) and allowing more firms to enter the special interest channel (Macher et al., Reference Macher, Mayo and Schiffer2011). Consistent with this understanding, Dür and De Bièvre (Reference Dür and De Bièvre2007, 4) observe the larger interest group population in the advanced industrial democracies, discussing how “several layers of decision-making open up new channels of influence and make it easier for [even] diffuse interests to influence policy outcomes.”

Second, restrictions should also narrow the special interest channel in autocracies. The non-democratic state's restrictions on societal freedom (i.e., repression) make it harder for many potential groups to organize formally, even when they represent concentrated interests and would otherwise be able to overcome the collective action problem, and to access the state even when they are able to organize clandestinely. While data on formal lobbying restrictions are quite limited on a cross-national basis, these restrictions tend to be greater in less democratic regimes (Chari et al., Reference Chari, Hogan, Murphy and Crepaz2020). And the comparative case studies of corporate lobbying in China and the United States offered by Gao (Reference Gao2006) accord with this general proposition. This is not to deny that there are many lobbying regulations in more democratic regimes like the United States, but these regulations are more aimed toward making special interest politics more transparent and less directed toward restricting the same (Holman and Luneburg, Reference Holman and Luneburg2012). Furthermore, there are often informal restrictions on lobbying in less democratic political systems. According to Thomas and Hrebenar (Reference Thomas and Hrebenar2008, 6), “special interests were often viewed with great suspicion and generally seen as illegitimate in authoritarian regimes.” Consequently, “a very narrow range of groups likely exists when the [authoritarian] system begins to transition to democracy” (ibid, 7 emphasis added).

Of course, even if organized groups (e.g., firms) can more readily access the democratic state, this does not mean that they actually choose to do so. First, more developed political-economies may better satisfy the needs of the actors within it, thereby reducing the demand for policy change. Thus, while firms could more readily lobby the state in more democratic regimes, they also might have a lesser need to engage in this political activity in more developed and mature national contexts. Second, and more importantly, a wider special interest channel in more democratic regimes may simply exacerbate the collective action problem. Given that lobbying remains costly even with greater access to the state, many firms may prefer to free-ride, hoping that other organized groups will lobby on behalf of their policy preferences. Following this logic, one would not expect to observe greater firm lobbying in more democratic political regimes because any lobbying advantage offered by greater access to the state would be offset by greater corresponding incentives to free ride.

However, Barber et al. (Reference Barber, Pierskalla and Weschle2014) tested Olson's (Reference Olson1971) hypothesis that there should be less lobbying in less concentrated industries, where firms arguably face a greater collective action problem and found no relationship between firm lobbying and industry concentration. Thus, to the extent that there appears not to be a large collective action problem—perhaps because firms perceive sufficient private goods within highly differentiated industries to justify their lobbying activity (Kim, Reference Kim2017)—we hypothesize that there should be a greater probability of firm lobbying in more democratic regimes.

1.2 The data

Testing this hypothesis requires cross-national data on firm lobbying, and there are very few datasets capturing this political behavior in different countries. Consequently, we use the WBES,Footnote 2 which interviewed firm managers/owners in a large set of mostly developing middle-income countries, thus providing good variation in terms of the political regime. The World Bank selected firms through stratified sampling to increase their representativeness in terms of location, size, and ownership (among other criteria). These surveys began in 2002, and the lobbying query (described below) was dropped after 2005. Within the 2002–05 period, 29,511 firms within 83 country/year surveys were offered the opportunity to answer a question about their lobbying behavior.Footnote 3 Table A1 in our online Appendix provides information about the number of firms appearing in each of these surveys.

Our dependent variable is a dichotomous measure of firm lobbying based on the query asking firm managers/owners to “[t]hink about national laws and regulations enacted in the last two years that have a substantial impact on your business. Did your firm seek to lobby the government or otherwise influence the content of laws and regulations affecting it?” (World Bank, 2002, 7). Lobby is coded as 1 if the firm responded “yes” and 0 if “no.” Among the 29,511 firms receiving this query, 29,352 answered it (for a response rate of 99.5 percent) with 15 percent responding in the affirmative. Descriptive statistics (including the response rate) are provided in Table A2 in our online Appendix.

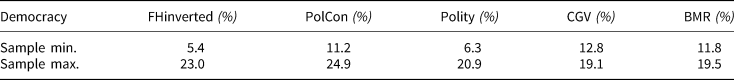

Our primary independent variable is the political regime type (Democracy) of the firm's country/year, using (in sequence) five different operational measures. We begin with the indicators considered by Weymouth (Reference Weymouth2012): Freedom House's combined measure of political rights and civil liberties, which has been inverted so that larger values indicate a more democratic regime (FHinverted)Footnote 4 and the quantity of political constraints (PolCon), or veto players, which increases with democracy (Henisz, Reference Henisz2000).Footnote 5 As the most commonly used regime type indicator, we next consider Polity (rescaled 0–20 for the interaction models in our online Appendix),Footnote 6 followed by two dichotomous indicators consistent with minimalist definitions of democracy: CGV (Cheibub et al., Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010) and BMR (Boix et al., Reference Boix, Miller and Rosato2013). These dichotomous indicators will be especially useful in the second section when we examine what firms lobby in democracies compared to non-democracies.

While the WBES represents the best (if not the only) available dataset to test arguments about firm lobbying across different political regimes, it does have certain problems that we must both acknowledge and address. The first concerns firm selection into these surveys. Firms, especially smaller firms, may be harder to reach and interview in less democratic regimes, which is problematic because research (e.g., Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Lincoln and Mishra2014) shows that the firm characteristic most strongly associated with lobbying activity is its size. The size measure with the least missing data in the WBES is the firm's number of workers, which we measure on a logged basis (Workersln).Footnote 7 Indeed, all five operational measures of Democracy show a significant negative correlation with Workersln.Footnote 8 Thus, firms that are more likely to lobby are comparatively over-represented in the surveys conducted in less democratic country/years, so we address this potential source of bias by always controlling for firm size.

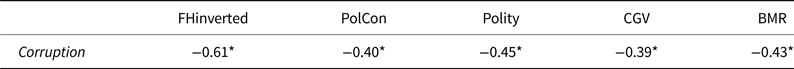

Second, there could be a problem of mis-response to the lobbying query. To clarify, mis-response is not the same as non-response. Indeed, there appears to be no particular problem related to the latter given that 99.5 percent of the firms receiving this question also responded to it. Likewise, we show in Table A3 in our online Appendix that there is no evidence that responding to the Lobby query is correlated with the political regime.Footnote 9 However, there could be mis-response based on the expectation that firms engaging in this special interest behavior might be perceived as corrupt, especially in less democratic political environments. On this basis, systemic corruption is a potential confounder for our hypothesis since it is negatively correlated with Democracy,Footnote 10 and it may also influence how firms report their lobbying behavior. To address this possibility, we control for the level of Corruption in the survey's country/year using data from Transparency International.Footnote 11

Likewise, lobbying patterns may change in more developed and mature political-economies with national development and maturity as factors that are also correlated with a more democratic political regime. To address the confounding problem related to economic development, we include the logged value of the country/year's Gross Domestic Product per capita (GDPpcln) using data from World Bank.Footnote 12 And to address the confounding problem related to the maturity of the national market, we take the logged value of the country/year's age since WWII (Market Ageln), which arguably marks the start of the current era of economic globalization.Footnote 13

Furthermore, to account for regional traditions in special interest behavior that may be correlated with Democracy per contagion theories of democratization, we include a set of regional dummy variables, using the World Bank's regional categories (East Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, South Asia with Sub-Saharan Africa as the omitted regional category).Footnote 14 Finally, given a democratization trend over the period of firm surveys, any trend in lobbying might be falsely assigned to the Democracy variable. Accordingly, we include a set of year dummy variables to proxy these temporal patterns.

1.3 The results

To test our hypothesis, we regress Lobby, measured at the firm-level, on the sequence of Democracy variables with variation at the survey (or country/year) level.Footnote 15 With variation at two levels, our models are estimated as hierarchical, or mixed-effects, models with survey random effects and the standard errors clustered on the country. These regressions begin with a simple specification that includes only the control variables described above. This basic specification addresses the primary sources of bias (e.g., firm selection, mis-response to the Lobby query, and various Democracy confounders) and, given missing data at the firm-level, it also maximizes our sample size (N = 28,617). We will later demonstrate the robustness of these results by adding a larger set of control variables at the firm level, which reduces our sample size by about 16 percent.

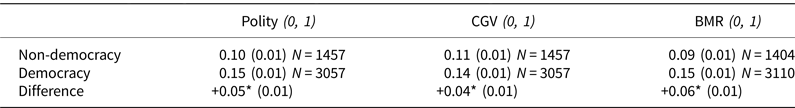

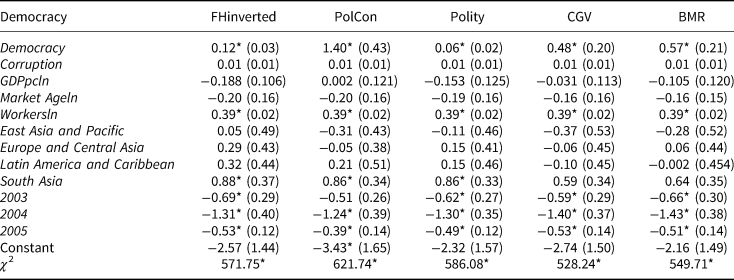

Table 1 provides five mixed-effects logit models of Lobby,Footnote 16 using each of the Democracy indicators in sequence to demonstrate robustness. For each indicator, the result is statistically significant and consistent with the hypothesis that a more democratic political regime is associated with a greater probability of firm lobbying. These results are also substantively significant. In Table 2, we provide the linear probability of the average firm lobbying across the range of Democracy values, moving from the sample's minimum to maximum value for each operational indicator. For the continuous measures, this probability effectively quadruples for FHinverted, triples for Polity, and more than doubles for PolCon. Using the coarser dichotomous measures, the probability of a firm lobbying in a democracy compared to a non-democracy is about 50 percent greater for CGV and about 65 percent greater for BMR.

Table 1. Models of Lobby

N = 28,617 firms across 83 country/year surveys. Mixed-effects logit coefficients with survey random effects and standard errors clustered on the country.

Sub-Saharan Africa is the omitted region and 2002 is the omitted survey year.

*p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Table 2. Probability of Lobby = 1

It is next important to demonstrate that these results are not simply an artifact of using the basic right-hand side specification in Table 1 with few firm-level controls. We thus add a large set of variables measured at the firm-level, so that our specification more closely parallels the one used by Weymouth (Reference Weymouth2012). However, as mentioned earlier, the addition of these firm-level controls reduces our sample size by about 16 percent (N = 24,107).

The extended set of right-hand side variables begin with the logged age of the firm in years (Firm Ageln) to account for its experience, expected to be positively correlated with lobbying. We next capture a locational advantage in lobbying the state by including a dichotomous variable Located in Capital. Our specification also controls for the percent of the firm owned by foreigners (Foreign Ownership) and the government (Government Ownership) since these attributes may not only affect their ability to lobby but be correlated with political regime type. Similarly, the percent of their Sales to Government and being Publicly Listed may influence the firm's access to the state and be associated with the political regime. Following Weymouth (Reference Weymouth2012), we also control for Domestic Inputs (as a percent of total inputs) and include dummy variables for the firms that report as Exporting and as multinational corporations (MNC). Finally at the firm-level, we control for the firm's sector of production with dummy variables for Manufacturing, Agriculture, Construction, and Services (with Other as the omitted sectoral category).Footnote 17

With this extensive right-hand side specification, Table 3 provides the same sequence of Lobby mixed-effects models using the different Democracy measures. Due to missing data at the firm-level, we lose 7 country/year surveys where one or more queries about the firm were not included in the WBES survey instrument (for whatever reason). Even with the addition of these firm-level control variables and corresponding reduction in sample size, each of the Democracy measures remains positively associated with firm lobbying. It is important to note that while we do not mark the positive CGV coefficient in Table 3 as statistically significant at the 0.05 level using a two-tailed test, it is statistically significant either at the 0.10 level using a two-tailed test or at the 0.05 level using a one-tailed test (which would be appropriate given our directional hypothesis).

Table 3. Additional models of Lobby

N = 24,107 firms across 76 country/year surveys. Mixed-effects logit coefficients with survey random effects and standard errors clustered on the country.

Sub-Saharan Africa is the omitted region and 2002 is the omitted survey year.

*p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Our final robustness check considers a change in the dependent variable, expanding the definition of lobbying to include indirect special interest pressure applied through a business association (BA). The WBES also queried firms if they were a “member of a business association.” Following this question, they were asked if their BA provided the service of “lobbying government” and how valuable this service was to the firm (World Bank, 2002, 4). If the firm indicated that this service was of at least some value to them (i.e., “minor value” or greater), then we treat their response as evidence of indirect lobbying through their BA. For a firm that meets this criterion, but did not report as directly lobbying, we recode their 0 (for Lobby) to 1, thus creating the new dependent variable LobbyBA.Footnote 18 Given that there are a handful of firms that did not answer the Lobby query, but did respond to the query above, our sample size also increases slightly from 24,107 to 24,150. This expanded definition of lobbying increases the percentage of firms engaging in this special interest behavior in both more and less democratic regimes, thus doubling the sample's average from 0.15 for Lobby to 0.30 for LobbyBA (see Table A2 in the online Appendix).

Table 4 presents the same sequence of models (using each Democracy indicator) with LobbyBA as the dependent variable. While some control variables gain or lose statistical significance compared to the Lobby results in Table 3, the Democracy coefficients remain positively signed and are statistically significant in all five models.Footnote 19 Comparing these coefficients in Table 3 (where Lobby is the dependent variable) with the same in Table 4 (where LobbyBA becomes the dependent variable), one can observe that they tend to attenuate in the latter (except for the CGV measure). These results obtain because while Democracy is positively associated with indirect lobbying only through a BA as shown in Table A4 where BALobbies (0, 1) becomes the dependent variable, the regime type/indirect lobbying relationship tends to be weaker than the regime type/direct lobbying relationship shown in Table 3. Thus, when we combine direct lobbying (Lobby) with indirect lobbying through a BA (BALobbies) to create the combined measure (LobbyBA), the Democracy results tend to weaken, but they all remain statistically significant in Table 4.

Table 4. Models of LobbyBA

N = 24,150 firms across 76 country/year surveys. Mixed-effects logit coefficients with survey random effects and standard errors clustered on the country.

Sub-Saharan Africa is the omitted region and 2002 is the omitted survey year.

*p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

2. Firm preferences within the special interest channel

Robust across five democracy indicators, different statistical specifications/samples, and multiple measures of lobbying, the results above provide what we believe to be the first systematic empirical evidence showing that there is greater lobbying, at least by firms, in more democratic political regimes. We also demonstrate in Table A5 in our online Appendix that, perhaps unsurprisingly, firm lobbying appears to matter in terms of self-reported policy Influence.Footnote 20 Arguably more surprisingly, these interaction models also show that the influence advantage enjoyed by lobbying firms does not significantly vary by political regime (i.e., lobbying appears to be more or less equally effective in democracies compared to non-democracies). Based on these results, the primary lobbying difference by political regime appears to be greater access or frequency in democracies compared to autocracies and not in the perceived effectiveness of this special interest behavior.

From this starting point, we now turn to the second task as discussed in the introduction: examining the mass of firms with different preferences for open trade and flexible exchange rates within the democratic special interest channel compared to the same in non-democracies. If it can be shown, for example, that as the special interest channel gets wider with democratization, firms with preferences for free trade and domestic monetary autonomy (consistent with flexible exchange rates) lobby more (for whatever reason), then we may be able to better understand why democratic states tend toward these foreign economic policies: they face greater special interest pressure to move in these directions. In terms of international trade, this demonstration would offer further evidence in support of Betz's (Reference Betz2017, 1250) argument that “tariff reduction…can be rent-seeking” with “the rents coming from groups that prefer tariff reductions.”

Before proceeding, it is important to clarify that this demonstration does not constitute proof that more open trade with greater domestic monetary autonomy in democracies is “caused” by greater firm lobbying for these outcomes, especially since there are other explanations that could also account for these results. However, it would be consistent with a special interest account for why democracies operate with these policies, assuming (not too heroically) that the state sets foreign economic policy based, at least in part, on the relative pressure from organized groups with different preferences. This assumption does not deny the possibility that the state may also set policy to accord with its own preferences. Instead, it simply proposes that even a self-interested state must take into account the policy preferences of the larger organized societal group or it risks losing political support and power.

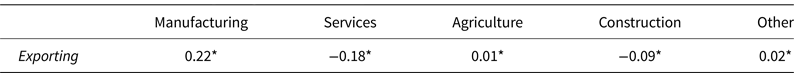

To compare the interests of firms within the democratic special interest channel compared to the same in non-democracies, we now sort them by their expected preferences in terms of international trade and currency policy. From the WBES data on (1) whether the firm exports and (2) its sectoral classification (manufacturing, services, agriculture, construction, and other), we can assign firms into three mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories: Exporting, Import Competing, and Nontradable. First, any firm that reports as an exporter (and is non-missing in terms of its sector), we classify as Exporting. Second, any firm that lies within a potentially tradable sector, defined as one that does not show a negative correlation with Exporting (i.e., Manufacturing, Agriculture, and Other), but does not report as an exporter is treated as Import Competing.Footnote 21 Third, any firm that lies within the sectors that show a negative correlation with Exporting (i.e., Services and Construction) and does not export is classified as Nontradable. These coding rules to identify firm preferences accord with those used by Broz et al. (Reference Broz, Frieden and Weymouth2008).Footnote 22

Our analysis now focuses only on lobbying firms (thus excluding non-lobbyers), comparing the percentage classified as Exporting in non-democracies compared to democracies. Considering that exporting firms have an expected preference for a more open trade policy (Milner, Reference Milner1988), we might be able to explain why democracies move in this direction based on special interest pressure if there is a greater mass of Exporting firms within their special interest channel. Using three dichotomous regime type measures including one based on the Polity measure,Footnote 23 the first column in Table 5 shows a significantly greater percentage of exporters within the special interest channel in democracies compared to non-democracies: an increase of 3 percent for Polity, an increase of 4 percent for CGV, and an increase of 7 percent for BMR.Footnote 24 Although it does not cleanly fit into our three mutually exclusive and exhaustive firm categories,Footnote 25 we also find a significantly larger percentage of multinational corporations (MNC), also with an expected preference for an open market due to their global supply chains (Osgood, Reference Osgood2018), within the democratic special interest channel.Footnote 26

Table 5. Comparing the percent of Lobby firms in three categories

Cell entries show the group's mean value by firm category with standard error in parentheses.

Difference based on a t-test with equal variances assumed.

*p < 0.05 (two tailed).

To complement the larger proportion of firms that lobby the democratic state for a more open trade policy, the second column in Table 5 also shows that there is a significantly smaller percentage of Import Competing firms with an expected preference for a more protected trade policy within the democratic special interest channel (compared to the same in non-democracies): a decrease of 19 percent for Polity and a decrease of 17 percent for both CGV and BMR. Thus, the democratic state appears not only to face more lobbying pressure in favor of free trade, but less for trade protection,Footnote 27 further helping to account for the finding that democracies tend to hold more open trade policies. This evidence directly accords with the argument advanced by Kim and Osgood (Reference Kim and Osgood2019, 410) about how “[i]nstitutional changes that facilitate lobbying” (e.g., democratization) should “strengthen the voices of primarily protrade actors.” Likewise, it fits with the argument by Frye and Mansfield (Reference Frye and Mansfield2003, 636) about the effect of democratization: “the dispersion of power from protectionist elites affiliated with the prior regime has created political space for interest groups favouring openness to increase their influence over trade policy.”

Models of currency policy preferences identify non-tradable firms as having a strong interest in domestic monetary policy autonomy (Frieden, Reference Frieden1991), defined as the ability to use the monetary policy instrument for an internal economic goal like growth or inflation control, which requires flexible exchange rates. The third column in Table 5 shows that there is a far greater percentage of firms classified as Nontradable within the special interest channel in democracies compared to non-democracies: an increase of 16 percent for Polity, 13 percent for CGV, and 10 percent for BMR.

Of course, exporters have an expected contrary preference for fixed exchange rates (Frieden, Reference Frieden1991), and we have already observed a greater percent of Exporting firms in the democratic special interest channel. However, the mass of Nontradable firms is not only consistently larger than the mass of Exporting firms within the democratic special interest channel (e.g., 0.46 versus 0.30 using Polity), the size advantage of Nontradable firms over Exporting firms is also consistently larger than the same in the non-democratic special interest channel (e.g., 0.16 (0.46–0.30) versus 0.03 (0.30–0.27) using Polity). Thus, even when we account for the growing counter-lobbying pressure of Exporting firms for fixed exchange rates, the larger growth in the lobbying mass of Nontradable firms favoring domestic monetary autonomy accords with the existing evidence that democratic states tend to operate with more flexible exchange rates.

In Table 6, we conduct the same analysis comparing the percentage of firms in these three categories within the special interest channel, but using the more expansive definition of lobbying that includes indirect lobbying through a business association (LobbyBA = 1). While the specific percentages are different in Table 6 (compared to Table 5), the basic patterns remain the same: (1) there is a greater mass of Exporting firms,Footnote 28 (2) a lesser mass of Import Competing firms, and (3) a greater mass of Nontradable firms within the democratic special interest channel with significant differences using all three dichotomous Democracy indicators.

Table 6. Comparing the percent of LobbyBA firms in three categories

Cell entries show the group's mean value by firm category with standard error in parentheses.

Difference based on a t-test with equal variances assumed.

*p < 0.05 (two tailed).

3. Discussion

This paper has considered the variation in firm lobbying by political regime type using data from the WBES. It first tested the hypothesis that this special interest behavior should be greater in more democratic regimes, providing the first set of empirical results to demonstrate this expected positive relationship. It then examined the percentage of firms within the special interest channel with different preferences in terms of foreign economic policy. Helping to explain why democracies have more open trade policies, our results showed a greater relative mass of exporting firms with an expected preference for free trade and a lesser relative mass of import-competing firms with an expected preference for trade protection within the democratic special interest channel. To help explain why democracies have more flexible exchange rate regimes, the results also showed a greater percentage of non-tradable firms with an expected preference for domestic monetary autonomy within the democratic special interest channel.

Given space constraints, we can offer no theory here for why there should be more firms favoring open markets and flexible exchange rates within the democratic special interest channel. However, there are two primary (and potentially complementary) explanations to account for these results. The first stems from firm creation within democracies. A different regulatory environment with greater market competition may facilitate the transition of tradable firms into exporting (Roosevelt, Reference Roosevelt2021) and the emergence of smaller non-tradable firms. The second possibility, developed by Bearce and Velasco Guachalla (Reference Bearce and Velasco-Guachalla2020), is that non-tradable and exporting firms are not necessarily less present within autocracies but are largely blocked from access to the narrow special interest channel, which is occupied by large but less competitive tradable firms with import-competing preferences. Having established these regime type differences in terms of the firms that lobby, an important next step is to better establish why such differences exist.Footnote 29

Another step would be to explore the lobbying variation among different types of autocracies and the same among different types of democracies. Starting with authoritarian regimes, one might split them into three types: civilian party-based dictatorships, military governments, and monarchies (Cheibub et al., Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010). And if one thinks of civilian party-based dictatorships as the most “democratic” among the authoritarian regime types, then it has already been shown they have more open trade policies and more flexible exchange rates compared to military governments and monarchies (e.g., Hankla and Kuthy, Reference Hankla and Kuthy2013; Steinberg and Malhotra, Reference Steinberg and Malhotra2014). Based on our argument, one might expect to observe greater lobbying, especially by exporting and non-tradable firms, in civilian party-based dictatorships compared to military governments and monarchies. Likewise, one can split democratic regimes based on their electoral system: majoritarian versus proportional representation (PR). It has already been shown that PR systems tend to have more open trade policies (e.g., Rogowski, Reference Rogowski1987; Rickard, Reference Rickard2012) and more flexible exchange rates (e.g., Leblang, Reference Leblang1999; Bearce, Reference Bearce2002). As a potential explanation for these results, our argument would predict greater lobbying in PR systems by exporting and non-tradable firms compared to majoritarian systems.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.79. To obtain replication material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AX4CT3.

Acknowledgments

An earlier draft was presented at APSA 2019 in Washington, DC. We thank the anonymous reviewers, Timm Betz, Bill Clark, Marco Martini, Iain Osgood, and Steve Weymouth for helpful comments.