The growing success of radical right parties (RRPs) has spurred considerable debate surrounding the causes and consequences of their ascent. A core question within both the academic and the broader public debate concerns the behavior of mainstream parties and how it affects the electoral fortunes of the radical right. The belief that accommodative strategies are beneficial, if not imperative in confronting radical right challengers remains widespread among politicians, pundits, and large parts of European publics. In political science, the influential work of Meguid (Reference Meguid2005, Reference Meguid2008) argues that niche parties are less successful when established parties choose accommodative strategies, i.e., when they emphasize the niche parties’ most important issue and coopt its issue position. Following this rationale, RRPs should be less successful when established parties adopt restrictive immigration positions. Empirical research indeed shows that mainstream parties seem to follow this rationale and overwhelmingly adopt accommodative strategies in response to radical right success (Han, Reference Han2015; Abou-Chadi, Reference Abou-Chadi2016; Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020).

In contrast, other scholars argue that the adoption of radical right positions by established parties legitimizes and popularizes this type of discourse. Increased salience of immigration, along with a discourse that has shifted toward the radical right, should therefore strengthen RRPs because voters—in the words of long-time Front National leader Jean-Marie Le Pen—“prefer the original to the copy” (Arzheimer and Carter, Reference Arzheimer and Carter2006; Dahlström and Sundell, Reference Dahlström and Sundell2012; Mudde, Reference Mudde2019).

In this research note, we provide a series of new tests on the (conditional) effectiveness of accommodative strategies on radical right success across a broad set of West European electoral contexts between 1976 and 2017. In contrast to Meguid (Reference Meguid2005, Reference Meguid2008) and other studies using data from the “third wave” (Mudde, Reference Mudde2019) of the radical right between 1980 and 2000, we thereby include many observations from the recent and persistent “fourth wave” of the European radical right. Furthermore, we present first-time evidence on how a large variety of context factors conditions the effectiveness of accommodative strategies, including characteristics of RRPs, their mainstream competitors, as well as the broader political context.

We investigate the electoral consequences of political accommodation at the macro level—focusing on RRPs’ election results—and the micro level—exploring vote switching between mainstream and radical right parties. Whereas our macro-level analyses speak to the question if mainstream party strategies can reduce support for the radical right, our micro-level analyses present novel evidence on the question if mainstream parties that accommodate benefit themselves by pulling voters from the radical right. In our analyses, we test whether accommodative strategies impact the change in RRPs’ vote share between two consecutive elections. We find neither general nor conditional support for the claim that accommodative strategies significantly reduce support for the radical right. To the contrary, voters are on average more likely to defect to the radical right when mainstream parties adopt anti-immigration positions, a pattern that has been particularly pronounced for established RRPs. Overall, our findings suggest that positional accommodation is fruitless in the best case, and can be detrimental in the worst case. This result contributes to existing experimental studies that directly address potential endogeneity issues between party position shifts and citizens’ voting behavior, but are limited in terms of the generalizability across political contexts (Hjorth and Larsen, Reference Hjorth and Larsen2020; Chou et al., Reference Chou, Dancygier, Egami and Jamal2021). Extensive robustness checks corroborate the credibility of our findings.

Our study contributes to a growing literature on the dynamics of party competition. It empirically challenges the widespread and persistent view that accommodation reduces support for niche parties and especially for the radical right. The implications of our study are, however, not only limited to the academic debate but also challenge the widely held belief in today's political debate that the adoption of more authoritarian-nationalist and anti-immigration positions by mainstream parties would curb the success of the radical right.

Empirical strategy

Our first set of analyses focuses on the party level. Here, we regress changes in radical right vote shares on the positional shifts of all relevant mainstream parties in a given election. We do so using a stacked data structure, where every outcome is replicated by the number of mainstream parties and subsequently matched with the policy shifts of each mainstream party. This allows us to analyze over 350 mainstream party strategies from 108 electoral contexts between 1976 and 2017.Footnote 1 We use linear models with country fixed effects and election-clustered standard errors. To account for the multiplication of identical outcomes due to stacking, we use fractional frequency weights such that, e.g., two duplicate radical right vote shares explained by the policy shifts of two different mainstream parties are each weighted by 0.5.

In a second step, we shift our attention to the individual level where we study vote switching between mainstream and radical right parties in consecutive elections. This is important because the aggregate view does not allow for isolating voter reactions to the strategic positioning of a given party. For instance, even if aggregate results suggested that accommodation reduces support for the radical right, this would not necessarily indicate that previous radical right voters switched to those parties that actively sought to accommodate the radical right. Instead, decreasing vote shares of RRPs could for example result from mobilizing former non-voters.

Using a newly compiled data set that marries voting data from rounds 2–4 of the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, the European Voter Project, and nearly 30 national election studies, we analyze 228 instances of voter migration between mainstream and RRPs across 70 elections from 13 West European polities. We again generate a stacked data matrix, which pairs individual respondents with each of the mainstream parties competing in the corresponding electoral context. Using recall questions on respondents’ voting behavior in the current and previous general elections, we record for each voter–party dyad if voters switched from the respective mainstream party to RRPs, from RRPs to the respective mainstream party, or neither.Footnote 2 We then use this switching indicator as the outcome variable in a series of hierarchical regressions models, where random intercepts at the party-election level capture nominal percentages of the RRPs’ voter transfers with a given mainstream party. Additionally, election and country level random intercepts capture the dependence among parties from the same electoral contexts and same countries, respectively. In line with the approach of our macro-level analysis, we explain this variation in aggregate dyadic losses, gains, and net transfers as a function of mainstream parties’ positional shifts on the immigration issue.

Our analyses at the macro and micro levels employ the same selection rules for the inclusion of mainstream and radical right parties, use identical codings for measures of party strategies, and employ analogous strategies for testing the conditional effectiveness of accommodative strategies and for the selection of control variables. For the measures of party strategies, we use data from the MARPOR Project (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2019) which provides parties’ policy positions based on their election manifestos. To derive immigration position scales, we combine items that capture positive and negative mentions in the categories National Way of Life and Multiculturalism. The most important advantage of these data is that they provide estimates of party policies cross-nationally and for an extended time period. Furthermore, the comparability of our results is ensured since these data were used in related studies (e.g., Meguid, Reference Meguid2008). Following the widely used procedure introduced in Lowe (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Slava and Laver2011), we aggregate the MARPOR items using logit-transformed scales.

The association between mainstream parties’ position shifts and RRP support might be influenced by a number of conditioning factors. We consider various arguments suggesting that the effectiveness of accommodative strategies depends on contextual factors through a series of interaction effects. First, Meguid's (Reference Meguid2008, 39, 51) work emphasizes that the effectiveness of positional accommodation hinges on the radical right life cycle: Accommodation should be most effective when radical right challengers first break through into the electoral arena and pose an initial electoral threat, as mainstream parties can still exploit a valence advantage. We thus distinguish three phases that capture the dynamics of electoral threat and valence competition: marginalization (little to no electoral threat), breakthrough (initial electoral threat, initial valence asymmetry), and consolidation (persistent electoral threat, open valence competition). Following Art (Reference Art2011), we conceptualize these phases in terms of electoral persistence: When the radical right gains at least five percent of the national vote for the first time, it enters the breakthrough phase; when it does so for at least three consecutive national elections, we consider it consolidated.

Second, radical right success has increasingly become a European-wide phenomenon (Mudde, Reference Mudde2019). We test whether the mainstreaming of radical right politics over time undermines the effectiveness of accommodation akin to a linear time trend. Third, we test whether accommodation is more effective when combined with a cordon sanitaire, i.e., when mainstream parties systematically rule out cooperation with RRPs (see e.g., Art, Reference Art2011; van Spanje, Reference van Spanje2018). In elections with multiple RRPs, we focus on the largest RRP to determine whether a cordon sanitaire is present, as it is arithmetically most important for prospective government formation and its chances of joining government are likely most important in conditioning electoral responses to mainstream party policy strategies.

Fourth, Meguid (Reference Meguid2008) also underlines that the success of RRPs depends on the joint strategic behavior of the mainstream parties in a party system. Thus, for each mainstream party in our sample, we observe the range of policy positions among its mainstream competitors. Depending on whether these competitors’ positions are all restrictive, all liberal, or both, we define a mainstream parties’ competitive environment as restrictive, as liberal, or mixed. Fifth, we separate proximate and non-proximate competitors to RRPs by subsetting our analyses to parties of the mainstream left (social democrats) and mainstream right (conservatives, christian democrats, and selected liberal parties). Sixth, extant work on party system agendas suggests that parties must compete on issues that voters consider important (Green-Pedersen and Mortensen, Reference Green-Pedersen and Mortensen2010). Accommodative strategies should thus be most effective when campaigns revolve around the immigration issue. We test whether accommodative shifts are more effective when immigration is a highly salient issue on the party system agenda. Lastly, Tavits (Reference Tavits2007) argues that policy shifts on value-laden issues tend to lack credibility. Following this rationale, accommodative repositioning should only be effective if it remains consistent with parties’ past positions. For that reason, we condition accommodative shifts on parties’ past positions.

We refer readers to the online Appendix for further information on data, measures, and models. Section A provides information on the electoral contexts and the selection of mainstream and RRPs. Section B details the measurement of party positions, provides in-depth descriptions of the moderators used for testing the conditional arguments, and describes all control variables. Corresponding summary statistics are reported in Section C. We provide additional explanations of the data structure and modeling choices in Section D. Regression tables can be found in Section E. Robustness checks, along with additional analyses, are reported in Section F.

Findings

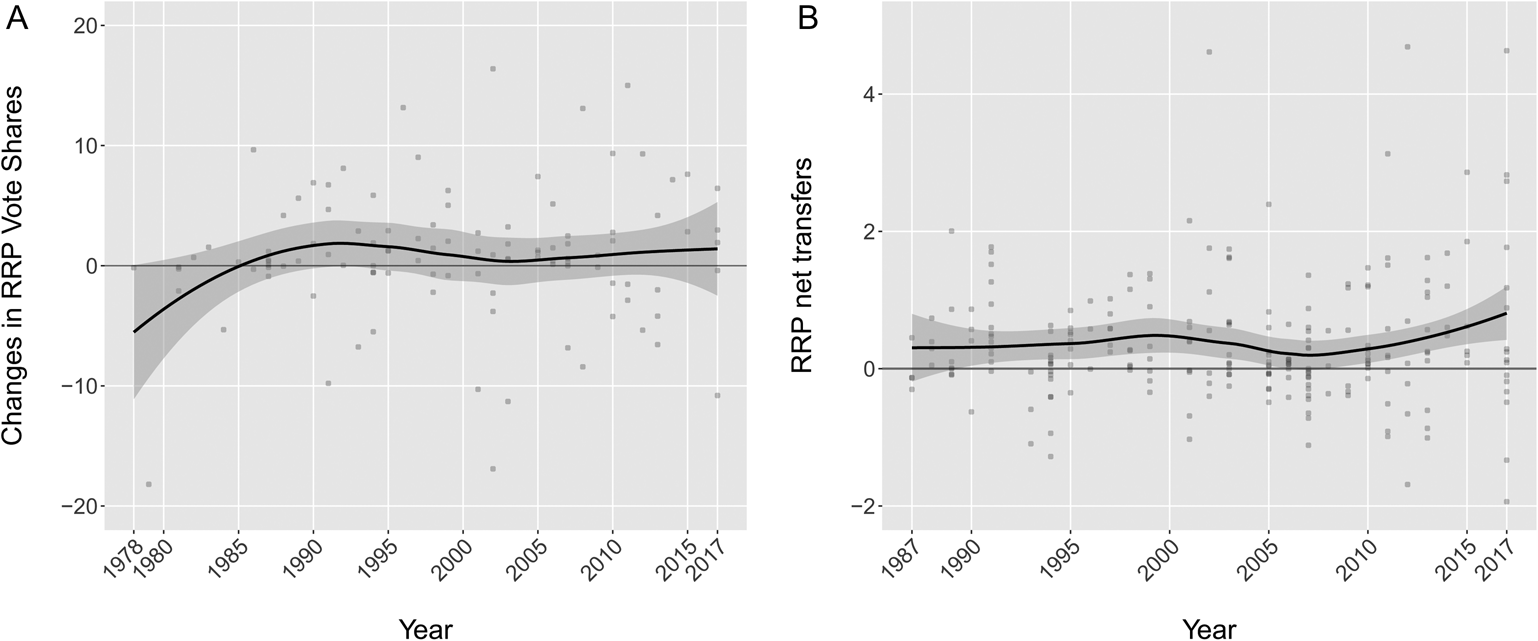

Figure 1 shows trends in radical right support akin to our two empirical approaches. Plot A, based on 108 election results, shows changes in macro-level radical right vote shares, 1976–2017. Plot B, based on micro-level survey data, shows dyadic RRP net transfers with 228 mainstream parties competing in 70 elections, 1987–2017. As we see in Plot A, RRPs have enjoyed average gains of 0.5–2 percentage points per election since the mid-1980s. Plot B reflects this pattern. Since the late 1980s, RRPs have, on average gained, 0.2–0.8 percentage points from each mainstream party. However, we also see considerable deviations from these average trends, both at the aggregate-level and in dyadic competition with mainstream competitors. We therefore turn to the questions if, and under which conditions, mainstream party policy shifts on immigration predict these variations in gains and losses.

Fig. 1. Trends in radical right gains/losses over time. (A) Changes in vote shares. (B) Survey-based radical right net transfers per mainstream party in a given election.

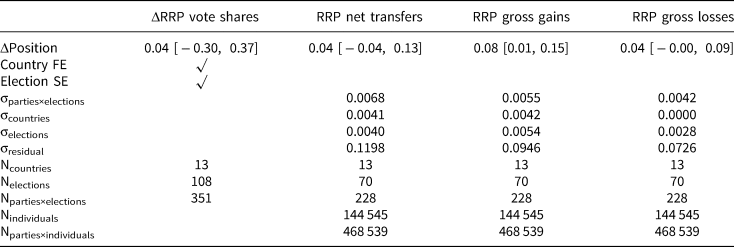

Table 1 shows the results of our analyses for the overall (i.e., unconditioned) effect. The first model shows the marginal effect of mainstream parties’ one unit shifts toward restrictive immigration positions on changes in radical right vote shares (in percentage points). For the micro-level findings, we report the effects of a given mainstream party's strategy on the percentage of voters that RRPs win from and lose to it (models 3 and 4), as well as the net balance of this trade (model 2).

Table 1. Reduced-form regression tables showing the effect of mainstream party policy shifts on various outcomes

Model 1: OLS with country fixed-effects and election-clustered standard errors. Models 2–4: hierarchical linear models with varying intercepts for countries, elections, and party-elections.

At the macro level, the marginal effect is close to zero and fails to reach conventional levels of statistical significance. Hence, there is no support for the claim that accommodating radical right positions weakens the radical right electorally. At the individual level, we gain a more nuanced picture. The estimates show that accommodative shifts catalyze voter transfers between mainstream parties and the radical right, predicting increases in both gains and losses of RRPs. Crucially, however, we find that accommodative policy shifts tend to do more good than harm to the radical right. The effect on gross radical right gains is pronouncedly positive, statistically significant, and clearly outweighs the effect on the increase in losses in terms of magnitude. Even though the overall net effect is statistically indistinguishable from zero, the findings thus show that rightward shifts on immigration result in significantly greater gains for RRPs and suggest that mainstream parties that move toward the radical right's core issue positions risk losing more voters to the radical right than they win in return.

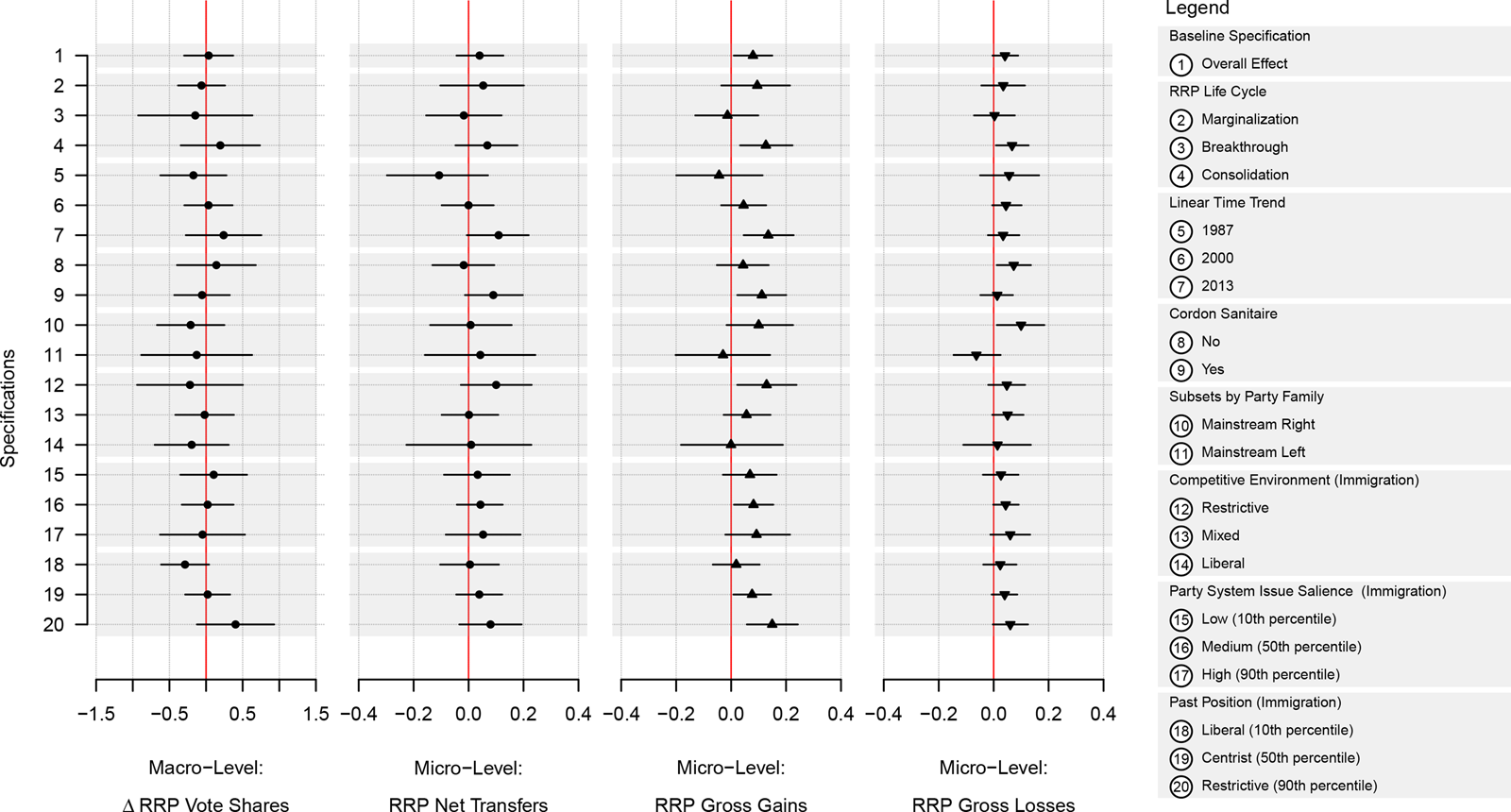

Next to this baseline specification, Figure 2 presents a series of alternative specifications that scrutinize the conditional impact of accommodative strategies. The findings show a clear picture: We find no significant effects at the 95 percent level on macro-level changes in the overall radical right vote share (first column).

Fig. 2. Alternative specifications—marginal effects with 95 percent confidence intervals.

Turning to the micro-level analyses that show net voter transfers (column 2) as well as disaggregated gross gains and losses (columns 3 and 4), we see some interesting insights into the patterns underlying the remaining null results. In particular, they show several conditions under which we can observe significant radical right gains as a result of mainstream party accommodation. Radical right gross gains are particularly pronounced when mainstream parties compete with RRPs that have become consolidated players in the electoral arena (spec. 4). In addition, we find that accommodative shifts have become increasingly ineffective over time, resulting in a significantly positive effect on net voter transfers to RRPs by the 2010s (spec. 7). These two findings suggest that accommodative strategies can benefit RRPs if they are more established players in their respective political arena.

Second and in contrast to previous findings presented in van Spanje (Reference van Spanje2018), the combination of accommodation with a cordon sanitaire does not play in mainstream parties’ favor: Accommodation is more effective in winning voters from the radical right in the absence of a cordon sanitaire and predicts greater losses to the radical right when employed in combination with a cordon sanitaire (specs. 8 + 9).

Lastly, the results suggest that too much co-optation of the radical right leads to gains for these challengers. On the one hand, where other mainstream parties already occupy restrictive immigration positions, RRPs gain strongly from parties that choose to accommodate (spec. 12). On the other hand, accommodative strategies predict higher radical right gains and losses when employed by parties that had previously assumed restrictive positions on these issues (specs. 18–20). This suggests that vote switching in response to mainstream party policy shifts is most pronounced in the competition of RRPs and mainstream parties with a hard-line stance on immigration. Again, we see that the effects on gains outweigh the effects on losses. Accommodating radical right issue positions does thus not benefit mainstream parties even if they can claim to toughen a stance that they previously advocated. In contrast, voters defect from these parties to the radical right in remarkable numbers.

Robustness checks

We subject our analyses to an extensive set of robustness checks. First, in Section B.1 of the online Appendix, we use three alternative measures for parties’ policy strategies, including the manifesto codings by Dancygier and Margalit (Reference Dancygier and Margalit2020), which explicitly focus on immigration. Second, we re-estimate our macro-level analyses using jackknife resampling at the country and the election level. Third, as our micro-level analyses use a smaller sample than our macro-level analyses for reasons of data availability, we re-estimate our macro-level analyses on the exact same subset of elections and parties as the micro-level analyses. Fourth, one factor potentially affecting the interpretation of our results is public opinion. It is possible that both our variables of interest—RRP vote shares and mainstream parties’ shifts—are simultaneously driven by shifts in voters’ preferences on the immigration issue. We examined the robustness of our results, while controlling for changes in public preferences toward immigration.Footnote 3 Fifth, we present analyses if only the electorally strongest RRP is considered instead of aggregating all relevant RRPs. Lastly, we also provide a more direct test of our macro-level analysis because the stacked structure of our data potentially obscures effects driven by shifts of entire party systems. We do so by estimating the effect of the average response of all mainstream parties on RRPs’ electoral support.

These robustness checks, reported in Section F of the online Appendix, strongly support our point that accommodative strategies fail to prevent, stop, or revert the rise of radical right parties. To the contrary, several specifications suggest that co-opting the radical right's core issue positions tends to benefit them electorally. While few findings are robust across all specifications, we find repeated evidence at the micro-level that RRPs win voters from mainstream parties following accommodation when they are consolidated competitors and when mainstream parties simultaneously employ a cordon sanitaire.

Across all robustness checks, we find in fact only one specification, focusing on marginal RRPs prior to their electoral breakthrough, which yields a signficantly negative, albeit substantively small, effect. This specification strongly resembles Meguid's (Reference Meguid2005, Reference Meguid2008) analysis in terms of sample and measures and thus seemingly corroborates her original findings. However, this finding is neither supported by the corresponding micro-level analysis nor by any of the other macro-level variants of the same scenario. It thus seems that our only negative finding is driven by a particular combination of sample and measure—and not indicative of the conditional effectiveness of positional accommodation of emergent RRPs.

Conclusion

In this research note, we investigate one of the core questions within the research on radical right success: Do accommodative strategies help to weaken RRPs electorally? Our analyses do not provide any evidence that adopting more anti-immigrant positions reduces the radical right's support. Combining macro- and micro-level evidence, we can demonstrate that this does not mean that voters are generally unresponsive to party repositioning. To the contrary, accommodative policy shifts by mainstream parties tend to catalyze voter transfers between mainstream parties and RRPs. While some of these transitions cancel out in aggregation, the radical right, if anything, seems to be the net beneficiary of this exchange.

Our findings have important implications for the literature on party competition and RRPs in particular. The idea that accommodation helps to reduce niche party success has become a working assumption in many other studies. This is especially the case in research on mainstream party reactions to niche party success. However, the findings of our article open up a puzzle. While it is well-documented that mainstream parties react to radical right success by shifting toward their policy position (van Spanje, Reference van Spanje2010; Han, Reference Han2015; Abou-Chadi, Reference Abou-Chadi2016; Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020), these strategies do not seem to pay off electorally. Future work focusing on intra-party dynamics and competition between mainstream parties should explore this discrepancy further.Footnote 4

As a note of caution, the associational character of our study is unable to rule out potential endogeneity. While this problem is common to comparative research on parties’ position shifts and vote choice, our study complements recent experimental work on the consequences of accommodative strategies that focus on isolated electoral contexts (Hjorth and Larsen, Reference Hjorth and Larsen2020; Chou et al., Reference Chou, Dancygier, Egami and Jamal2021). On a broad comparative basis, our findings substantiate these studies by indicating that accommodative strategies will not pay off for mainstream parties. Nevertheless, future research should address this topic further with research designs suitable for causally identifying the effects of party strategies on voter behavior across different political contexts. One related point is to extend our analyses to multiple issues. Future research should also take into account that party system dynamics are inherently inter-related. Research should thus take up the conceptual and methodological challenge for an encompassing approach to vote switching between parties and patterns of voter mobilization and abstention.

In addition, our research can inform the current broader debate about the success of RRPs in Europe. Commentators and politicians alike often seem to be convinced that (a) the success of the radical right is a consequence of too centrist positions of mainstream parties and that (b) more anti-immigrant positions especially from mainstream right parties should help to weaken the radical right again. Our study provides support for neither of these claims. On the contrary, our findings suggest that, if anything, accommodative strategies of mainstream parties strengthen the radical right. This is supplemented by the finding that mainstream parties do not seem to benefit from accommodative strategies. There is no effect for either the mainstream right or the mainstream left in terms of their voter support, according to our analyses. When mainstream parties pick up radical right issues, they rather run the risk of legitimizing and normalizing radical right discourse and strengthening the radical right in the long run.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2022.8. To obtain replication material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GBWB8I