1. Introduction

This paper argues that liberal democratic states face a dilemma with immigrant integration: in enacting the policies to incorporate immigrants into public life, they also have to take into account public opinion and, in particular, their less tolerant citizens' reactions. In line with the notion of “opinion backlash” (Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016), liberal policy decisions concerning immigrants' political rights act as events that cause a negative reaction among some citizens which in turn triggers negative attitudes and increases the intolerance toward this group. Thus, liberal democracy may bring about and foster the very conditions that undermine it.

Currently, this challenge presents itself in Western democracies that seek to politically integrate Muslim immigrants—a group of increasing political importance but whose traditional religiosity is sometimes viewed as a detrimental to Western liberal values, secularism, and maybe even democracy itself (Norris and Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2004; Sniderman and Hagendoorn, Reference Sniderman and Hagendoorn2007; Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Petersen, Slothuus and Stubager2014; Adida et al., Reference Adida, Laitin and Valfort2016; Helbling & Traunmüller, Reference Helbling and Traunmüller2020). Although Muslims often stand at the center of such debates, clearly not all immigrants are Muslim—and Christian immigrants also often hold very traditional views and values that are at odds with a liberal mainstream. The aim of this paper is to investigate how native citizens react toward the permission and banning of public demonstrations by different religious immigrant groups.

Several recent studies have suggested that citizens' tolerance toward immigrants depends, among others, on the nature of “policy regimes,” that is, the political and cultural rights granted to immigrant groups (e.g., Weldon, Reference Weldon2006; Wright, Reference Wright2011; Wright and Bloemraad, Reference Wright and Bloemraad2012). According to this line of research, liberal policies have a socializing effect and foster liberal attitudes among citizens whereas restrictive policies correspond to more critical feelings toward immigrants. The backlash argument presented here challenges and qualifies this optimistic view. Backlash may mean that public opinion as a whole turns against the thrust of a policy decision (e.g., Abrajano and Hajnal, Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2015). Or, as in this paper, it can refer to an increasing polarization where the opinion of those who agree and those who disagree with a policy are pushed in opposite directions (e.g., Aaroe, Reference Aaroe2012; Hersh and Schaffner, Reference Hersh and Schaffner2013).

We demonstrate that attitudes concerning religious immigrants and their rights result from an interaction between specific policy decisions and individual differences in policy preferences. Citizens who agree with a liberal policy stance become more sympathetic, while those in favor of restrictive policy become more critical of religious immigrants. This psychological process which we describe closely resembles what Stenner (Reference Stenner2005) has called “the authoritarian dynamic,” where instances of “normative threat,” such as controversial policy decisions that grant political rights to controversial groups, both activate and interact with authoritarian predispositions which then go on to produce expressions on intolerance (see also Feldman and Stenner, Reference Feldman and Stenner1997; Haidt, Reference Zagarri2016).

Our findings on the effects of policy decisions on citizens' attitudes toward immigrants are based on a large-scale survey experiment with over 4000 respondents in the UK. The experimental design has two key elements which allow us to study the backlash argument: (a) an experimental manipulation of the policy decision (i.e., a “ban” versus “permit” of demonstration) and (b) an experimental manipulation of different immigrant groups. The latter follows the logic of a “cross-category comparison” design as recently discussed by Sniderman (Reference Sniderman2018) (see also Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Slothuus, Stubager and Togeby2011 and Helbling and Traunmüller, Reference Helbling and Traunmüller2020 for a similar experimental design). The logic of this design is that if we want to understand intolerance toward “Muslim immigrants” we need to compare the attitudes toward this particular group with attitudes toward both “Non-Muslim (e.g., Christian) immigrants” and “Muslim non-immigrants (i.e., natives).” By also manipulating the religiosity of the social groups we gain additional leverage by separating “Secular or devout Muslims” from “Radical Muslims” and, importantly, by comparing “Secular or devout Muslims” to “Radical Christians.” This additional manipulation casts the described immigrant groups in terms of their social liberalism and thus their potential threat to mainstream society.

The UK is a well-suited case to study our backlash argument. On the one hand, its policy regime regarding immigrant integration and citizenship is usually described as “multiculturalist” or “individualistic-civic” with a liberal stance toward immigrants' cultural and political rights (e.g., Weldon, Reference Weldon2006; Koopmans et al., Reference Zagarri2005). Countries that are more open toward immigrants' rights, that is, who possess a more favorable opportunity structure, generally witness more demands from immigrants and claims for their rights (Koopmans et al., Reference Koopmans, Statham, Giugni and Passy2005). On the other hand, and as many other Western democracies, the UK has experienced a surge in so-called “populist” sentiment and dissatisfaction with established politics. The most notable expression of this development is the outcome of the 2016 Brexit referendum where 51.9 percent of the voters had voted to exit the EU. Many observers agree that immigration was the key decisive issue for those citizens that voted “leave” in the referendum. Finally, the UK has known important and highly controversial migrant demonstrations, such as the recent protests by Muslim communities against LGBT lessons in school.Footnote 1

The results of our survey experiment broadly support the backlash argument and contribute to recent debates on public attitudes toward immigrants in general (Hainmueller and Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014) and Muslim immigrants in particular (Sniderman and Hagendoorn, Reference Sniderman and Hagendoorn2007; Strabac and Listhaug, Reference Strabac and Listhaug2008; Kalkan et al., Reference Kalkan, Layman and Uslaner2009; Saroglou et al., Reference Saroglou, Lamkaddem, van Pachterbeke and Buxant2009; Van der Noll, Reference Van der Noll2010; Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Petersen, Slothuus and Stubager2014; Adida et al., Reference Adida, Laitin and Valfort2016; Spruyt and Van der Noll, Reference Spruyt and Van der Noll2017; Van der Noll et al., Reference Van der Noll, Saroglou, Latour and Dolezal2017; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Johnston, Citrin and Soroka2017).

Our finding has important implications because what citizens think about immigrants and their rights impact several challenges facing Western democracies: concerns over civic cohesion (Kalkan et al., Reference Kalkan, Layman and Uslaner2009), the acceptance of asylum policy regimes (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2016), the political response to terrorism (Sides and Gross, Reference Sides and Gross2013; Dunwoody and McFarland, Reference Dunwoody and McFarland2017), and the support for right-wing populist parties (Norris, Reference Norris2005; Werts et al., Reference Werts, Scheepers and Lubbers2013). The results of this paper open up a new way of understanding these attitudes because they focus on policy decisions of political actors. The current political conflict over migrant integration then emerges not only as struggle between immigrants and their receiving society but between citizens and their political elites. We believe that this paints a more realistic picture of current political challenges in Western democracies and of the inherent policy dilemma political elites face in the integration of immigrants.

2. How does integration policy affect attitudes toward immigrants?

Recent studies have established a strong association between integration regulations and citizens' attitudes toward immigrants. All of these studies concur in the idea that integration policies have a direct influence on individual attitudes toward immigrants and that citizens tend to follow the general thrust of these policies. Weldon's (Reference Weldon2006) study reports that countries with individualistic-civic regimes are more tolerant than collectivistic-ethnic regimes. Ariely (Reference Ariely2012) suggests that individuals in countries with a jus soli regime express less xenophobic attitudes than individuals in countries with a jus sanguinis regime. Schlueter et al. (Reference Schlueter, Meuleman and Davidov2013) find that more liberal citizenship regimes are related to lower levels of perceived immigrant threat. Finally, Wright (Reference Wright2011) argues that more immigrant-inclusive definitions of the national community are found in countries with a jus soli regime.

In sum, these studies adopt a socialization perspective, look at the average policy effects on the population and (at least implicitly) assume a consensus among citizens. After all, liberal regimes are supposed to breed liberal citizens whereas restrictive regimes lead to intolerant citizens. Although such long-term socialization processes may well exist, clearly, this view leaves no place for disagreement and polarization in the short term. This strikes us as unrealistic given how polarized public debates over immigration are (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Helbling, Hoeglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012).Footnote 2

Instead of assuming citizen consensus, we build on studies showing that the general public holds conflicting views and often disagrees with the liberal policies implemented by political elites. Teney and Helbling (Reference Teney and Helbling2014) show such attitudinal gaps for a range of policy questions related to immigration, such as the opening of national borders. Similarly, Bansak et al. (Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2016) suggest that European publics have preferences for asylum policy that run counter to existing regulations. More importantly, this disconnect between citizen and political elites is a major source of citizen disaffection (Crouch, Reference Crouch2004) and an important explanation for the raise of populist parties (Ignazi, Reference Ignazi1992; Mudde, Reference Mudde2007).

We focus on the disagreement between citizens' preferences and elite decisions to understand citizens' opinions toward immigrants. The notion that policy decisions that are disliked or that threaten the status quo cause a negative reaction that adversely affects the group profiting from the policy is known as “opinion backlash” (Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016). Backlash reactions have been documented to affect several minority groups, including ethnic or racial groups (Bratton, Reference Bratton2002; Preuhs, Reference Preuhs2007), women (Zagarri, Reference Zagarri2007), and sexual minorities (Fejes, Reference Fejes2008, but see Fontana and Braman, Reference Fontana and Braman2012; Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016).

We expect that similar mechanisms in public opinion will also apply to policy decisions regarding the rights of immigrants in general and Muslim immigrants in particular. Although we aim at taking a more general view at attitudes toward religious migrants, the current literature focuses mostly on Muslim immigrants. As Helbling and Traunmüller (Reference Helbling and Traunmüller2016: 393) argue, accommodating Muslim immigrants' claims often “involves the changing of existing rules as well as the loss of longstanding traditions, valuable privileges, and maybe even everyday habits.” Some consider Muslims’ cultural beliefs on gender roles or sexuality as incompatible with liberal and secular lifestyles (e.g., Norris and Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2004; Sniderman and Hagendoorn, Reference Sniderman and Hagendoorn2007; Saroglou et al., Reference Saroglou, Lamkaddem, van Pachterbeke and Buxant2009; Van der Noll, Reference Van der Noll2010; Helbling, Reference Helbling2014). Others argue that Muslim immigration threatens the collective identities in Europe because the latter are deeply rooted in a religious tradition of Christianity (Helbling and Traunmüller, Reference Helbling and Traunmüller2016). As a result, some citizens may view liberal policy decisions, which afford cultural or political rights to Muslim immigrants, as a threat to their own rights and identity.

3. Backlash to policy decisions

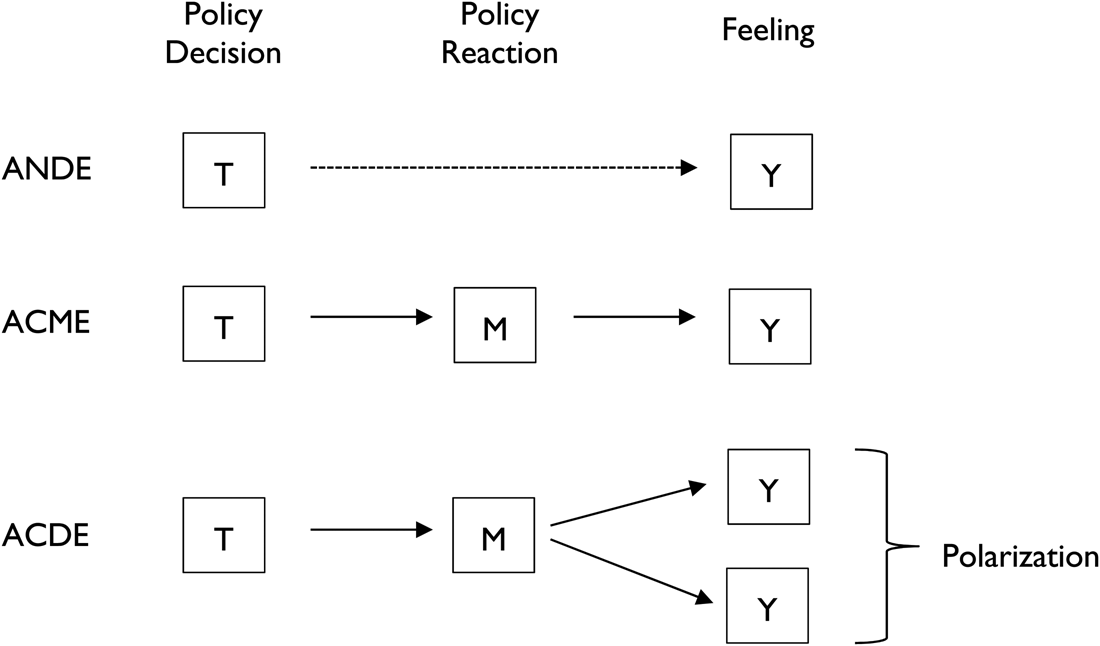

Following the idea of opinion backlash, our theoretical argument relates three variables to each other. We argue that policy decisions lead to a reaction among citizens, which then goes on to produce feelings, resulting in the following causal chain: Policy Decision (T) → Policy Reaction (M) → Feelings (Y). The key notion in our backlash argument is that it is citizens' reaction and more precisely their disagreement or rejection of a policy decision that triggers negative feelings toward groups benefitting from the decision.

To understand why this is the case and how we could think about the mechanism that produces this causal chain, we rely on what Stenner (Reference Stenner2005: 13) has called “the authoritarian dynamic.” It describes a psychological process where an event activates and interacts with an individual predisposition which then goes on to produce an expression of intolerance (see also Feldman and Stenner, Reference Feldman and Stenner1997, Haidt, Reference Haidt2016). A key feature of Stenner's (Reference Stenner2005: 16) argument is to distinguish between the predisposition and its manifestations, or in terms of the causal chain, to separate M and Y. According to Stenner, a predisposition is simply a stable tendency to react in a particular way to certain objects or events. But this stable predisposition has to be “switched on” in order to manifest its effects. In this sense, it is itself a post-treatment variable. What makes the predisposition “authoritarian” is the preference for uniformity as well as the consequent preference for group authority over individual autonomy.

Now the question is when and under what conditions an authoritarian predisposition produces manifestations of intolerance. Here Stenner (Reference Stenner2005: 17) argues that the predisposition is activated by “normative threat.” Normative threats are challenges to the existing order and in particular “questioned or questionable authorities and values” (Stenner, Reference Stenner2005: 17). These threats—which may well include policy decisions that grant political rights to groups with questionable values—trigger authoritarian preferences for conformity and the desire for restrictions of individual autonomy, including a ban of public demonstrations. Activated by normative threat the authoritarian predisposition then results in an increased rejection of and negative feelings toward out-groups, such as for example religious immigrants. Therefore, in a nutshell, the authoritarian dynamic describes a causal chain where normative threats (T) act as critical catalyst for the activation of authoritarian predispositions (M) which then in turn produce intolerant attitudes (Y).

An important assumption in this argument is that people vary in their predisposition so that different people react differently to instances of normative threat. Thus, we view feelings toward religious immigrants as resulting from an interaction between specific policy decisions and individuals' policy preference. Negative feelings toward religious immigrants result when an individual disagrees with and rejects a liberal policy proposal and its expected consequences. Of course, the effect of policy decisions may also run in the opposite direction: restrictive regulations which are viewed as being overly restrictive or even discriminating toward immigrants may evoke feelings of increased solidarity with this group.

An authoritarian disposition is politically color blind. It is a disposition that gets switched on when a person's normative order is threatened but it is a priori indifferent to what the content of this normative order may be. Therefore, if the normative order of liberals is threatened (e.g., by discriminatory behavior against immigrants) the authoritarian dynamic kicks in and leads to a rejection of the perceived source of threat (e.g., right-wingers, “fascists”) and, as a further consequence, an increased defense of and solidarity with the perceived target (e.g., immigrants). Either way, the effect of policy decisions on the attitudes toward immigrants will depend on citizens' support or opposition of these decisions. This leads to the intricacy that the policy reaction (M) should be viewed as both, a mediator and a moderator at the same time: a moderating mediator.

Feldman and Stenner (Reference Feldman and Stenner1997: 762) have shown “that certain types of threat polarize the attitudes of those high and low in authoritarianism, causing high authoritarians to become more intolerant and punitive, while low authoritarians become less so.” They also report that it is political threat—the perceived ideological disagreement with political elites—that has particularly polarizing consequences for the tolerance of out-groups. This is exactly the mechanism we believe to be at work in the context of integration policy decisions and attitudes toward religious immigrants.

4. Hypotheses

In sum, we argue that policy decisions on religious migrant political rights affect citizens' attitudes toward religious migrants depending on their agreement with the policy decisions. Citizens who agree with a liberal policy stance become more sympathetic, while those in favor of a restrictive policy become more critical of religious immigrants. We give a more formal description of our hypothesized causal mechanism in the Supplementary material. There we define more precisely how we think about the policy effect on citizens' attitudes toward religious immigrants and lay open the assumptions needed to identify and estimate this effect. Since our theoretical argument stresses the importance of citizens' policy reaction, we decompose the policy effect in two parts: an indirect or mediated effect that runs via citizens' reaction—and thus captures our argument—and a direct effect that captures all possible remaining policy influences on citizens' attitudes (cf. Imai et al., Reference Imai, Keele, Tingley and Yamamoto2011).

We are interested in the average causal mediation effect (ACME), that is, how the population thinks about religious immigrants compared to how the population would think about them if we changed their policy reaction, while holding the actual policy constant. In contrast, the average natural direct effect (ANDE) subsumes all policy effects that impact public opinion on religious immigration but which do not work through citizens' critical response. Finally, our main argument is captured by the average controlled direct effect (ACDE). Although the ACME describes how the outcome changes with a treatment-induced change in the mediator, the ACDE captures the treatment-induced change in the outcome as a function of the value of the mediator: the first is the mediating effect of the mediator, the second is the moderating effect of the mediator (Imai et al., Reference Imai, Keele and Yamamoto2010a). In terms of our research interest it quantifies how a specific degree of support or opposition to liberal policy decisions affects its impact on attitudes toward immigrants.

Figure 1 summarizes the mechanisms underlying our hypotheses. Policy decisions concerning the rights of religious immigrants shape the feelings toward them via citizens' policy reaction (H1). Thus, we would expect to see a significant ACME, but not an ANDE. Moreover, the direction of the effect of policy decisions on feelings toward religious immigrants will depend on a citizen's support or opposition toward the policy (H2). Thus, we would expect to see a polarization in terms of significantly different ACDEs.

Figure 1. The causal mechanisms of backlash to policy decision.

5. Data and methods

To test the causal impact of policy decisions on citizens' attitudes toward immigrants we conducted an online survey experiment in the UK in June 2015. Based on their online access panel of over 360,000 British adults, YouGov provided us with a sub-sample of N = 4468 respondents who are representative of the general national British population in terms of age, gender, social class, region, party identification, and newspaper readership. Selected panelists were invited by email to visit a website where they could answer the survey and receive a small cash reward.Footnote 3 In our particular sample 51 percent of the respondents are female with a mean age of 50 years (SD: 15.8 years). The youngest is 18 and the oldest 86 years old. Some 47 percent hold a university degree and 91 percent identify as white British. Since our theory really concerns the majority's reaction to immigrant rights, we have decided to restrict our sample to white British respondents and to run all of our analyses on this subset of our data. Although findings do not change much, they have a clearer interpretation: they refer to attitudes of the majority population in Britain.

6. Experimental setup

Our experimental design is based on a full factorial vignette analysis (Auspurg and Hinz, Reference Auspurg and Hinz2015) that manipulates the immigrant status of a fictitious group (immigrants from Bulgaria and immigrants from Nigeria or native British), their religious denomination (Muslim or Christian), and their degree of religiosity (non-practicing, devout, or radical). Importantly, respondents were randomly assigned to either of two different policy decisions of how to deal with the religious group's demand to hold public demonstrations. Although the first is a liberal policy response to the demands made by the group, the second adapts a restrictive policy approach. Respondents were asked whether they supported or opposed the policy proposal. We then recorded respondents' general feelings toward these groups and to what extent they thought these groups deserved welfare benefits and should have further political rights.

Each respondent was presented with a single vignette as follows (varying the groups' immigrant status, religion and religiosity, and policy decision):

“Now we are interested in your opinion regarding some groups that are currently active in social and political life in Great Britain. Imagine a group of immigrants from Nigeria who are devout Muslims who regularly go to the mosque and regularly pray at home. Members of this group want to hold public rallies and demonstrations for a better recognition of their interests in Britain. The authorities propose to permit these demonstrations.”

We restricted our vignettes to Muslim and Christian groups as the former constitute a controversial immigrant group in Great Britain (and most Western European countries) and the latter the traditional majority religion in Great Britain. In the vignettes seculars were defined as persons who never go to church/mosque and never pray. Devout persons regularly go to church/mosque and regularly pray. Radicals think that there is only one interpretation of the Bible/Koran that is for them more important than British laws. We decided to describe immigrants as coming from either Bulgaria or Nigeria as we wanted to select countries where both Muslims and Christians exist to make the vignettes realistic. In Nigeria, Muslims make up roughly 40 percent and in Bulgaria 10 percent of the population (Johnson and Grim, Reference Zagarri2013). Moreover, both nationalities constitute important migrant groups in Great Britain. Due to its colonial past there have been large migration flows from Nigeria over the last half-decade. EU enlargement in the mid-2000s has led to increased immigration from Eastern Europe. Focusing on Bulgarian and Nigerian immigrants allows us to vary cultural distance and to differentiate between EU and non-EU migrants.

Importantly, respondents were randomly assigned to either of two different policy decisions concerning the group's exercise of the democratic right to hold public demonstrations (T).Footnote 4 The first provides the respondents with a liberal policy decision to the demands made by the religious group (“The authorities propose to permit these demonstrations”) and the second frames the vignette in terms of a restrictive policy decision (“The authorities propose to ban these demonstrations”).Footnote 5 Although respondents are only presented fictional descriptions, this experiment closely resembles how many citizens would experience the policy decisions in a more natural setting. The average citizen would learn about the authority decision in an indirect fashion, either by reading about it in a newspaper or hearing about it in a discussion among acquaintances. Concerns about the external validity of this experiment are therefore likely to be minor.

After the vignette on the public demonstrations and authorities' decision, we first elicited respondents' policy reaction (M) by asking: “How would you react to such a permit/ban?” The answer categories were “Strongly support,” “Support,” “Neither support nor oppose,” “Oppose,” and “Strongly Oppose.” We then asked them to indicate their general feelings toward the religious group just described in the vignette. The question text reads as follows:

“Now we would like to know what your general feelings are about this group. We'd like you to rate them with a feeling thermometer. Ratings between 50 and 100 degrees mean that you feel favorably and warm toward them; ratings between 0 and 50 degrees mean that you don't feel favorably towards them and that you don't care too much for them. If you don't feel particularly warm or cold toward them you would rate them at 50 degrees.”

We use the feeling thermometer scores as the final outcome variable (Y) in our analysis and test how it is affected by the policy treatment and citizens' reaction to the regulation proposed by the authorities.

6.1 Statistical analysis

The estimations of the different causal effects (ACME, ANDE, and ACDE) proceed in several steps (see the Supplementary material for a more technical description and additional analyses). We first assess whether liberal or restrictive policy decisions by the authorities (T) have a causal effect on citizens' policy reactions (M). Here, we combined the answers of both experimental groups such that higher values correspond to greater support of the permission or greater opposition to the ban of the demonstration.Footnote 6 This regression equation includes all vignette characteristics along with basic pre-treatment covariates: sex, age, education, political ideology, and religiosity.Footnote 7 Since we found that empirically the distinction between Bulgarians and Nigerians did not matter much, we collapsed both groups into a single category “immigrant.”Footnote 8 We rely on ordinary least squares regression because it is easy to interpret and, more importantly, it allows for a more straightforward sensitivity analysis (see further below). We deal with missing data in covariates by imputing five complete data sets, running all models on each of these data sets and presenting the combined results (Little and Rubin, Reference Little and Rubin1987).

In a second step, we model citizens' general feeling toward that group (Y) using a second equation including the treatment (T), the mediator (M), vignette characteristics, and the same basic pre-treatment controls. We also enter a multiplicative interaction term between policy decision and citizen reaction to allow for the possibility that the mediation effect depends on treatment status.

Table S5 in the Supplementary material presents the model results for the mediator and outcome equation, respectively. Based on the estimates from these two model equations, we then employ the algorithm proposed by Imai et al. (Reference Imai, Keele and Yamamoto2010a, Reference Imai, Keele and Tingley2010b) to calculate the ACME and ANDE. Finally, we estimate the ACDE using the algorithm proposed by Acharya et al. (Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016).

7. Results

7.1 How citizens' reactions mediate the effect of policy on feelings

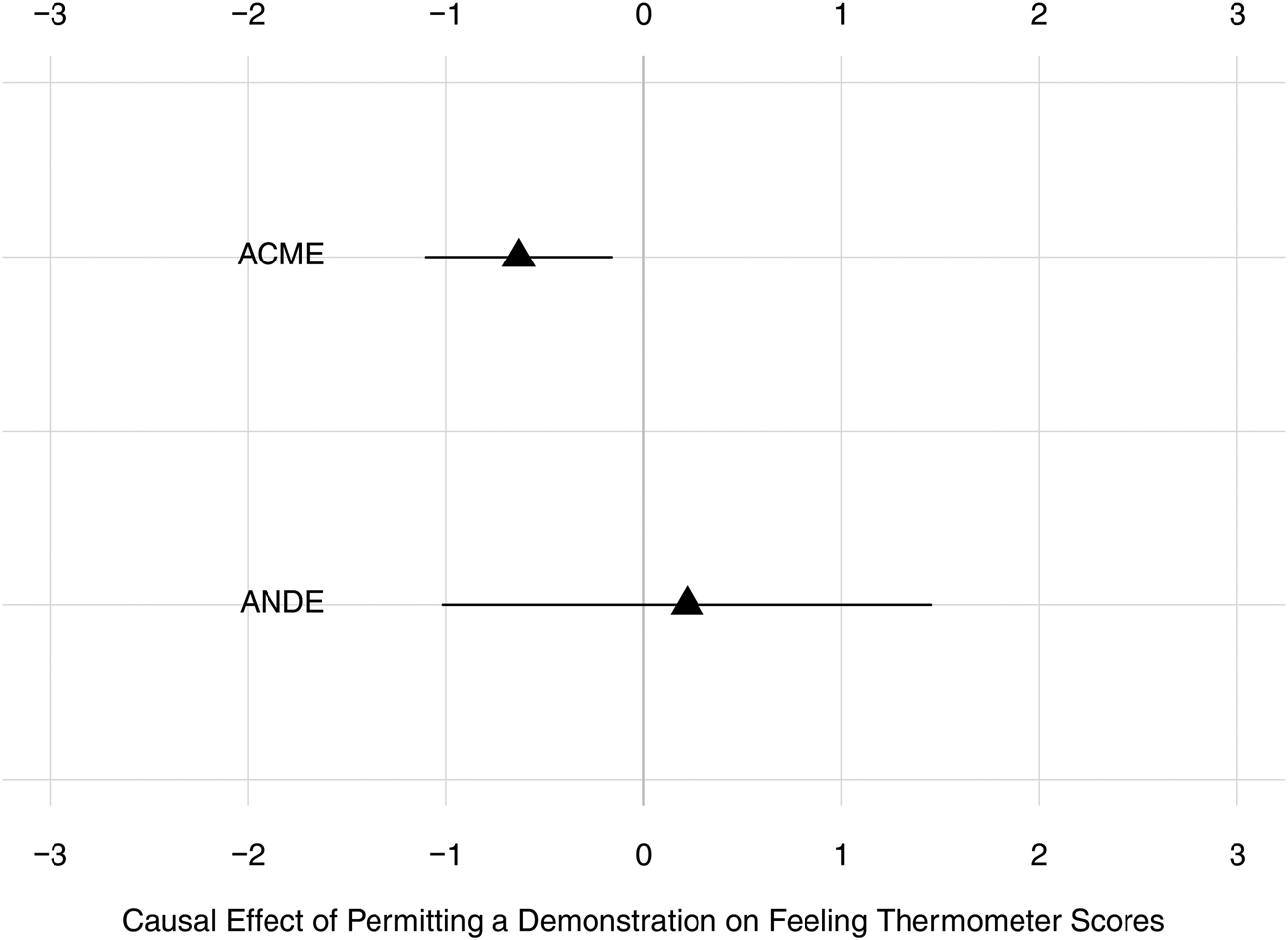

Figure 2 presents the ACME and ANDE of policy decisions on feeling thermometer scores. The first effect quantifies the difference in how the population feels about religious groups compared to how the population would feel about the groups if we only changed their policy reaction, but kept the actual policy constant. The second effect quantifies the difference in how the population feels about religious groups if we changed the policy but kept their reaction constant.Footnote 9

Figure 2. AMCE and ANDE of permitting a demonstration on feeling thermometer toward religious groups along with 95 percent CIs (based on 1000 simulations). Combined effects from five multiply imputed data sets.

Although the estimated ACME is statistically significant, the estimated ANDE is not. This suggests that the policy treatment of authority permission causes negative general feelings toward religious groups because citizens tend to react negatively to liberal regulation of public demonstrations of religious groups. Although the reported effect is small in substantive terms (−0.63 [95 percent confidence interval (CI): −1.10, −0.16]), it does provide evidence that changes in feelings toward religious groups result from citizen reactions triggered by regulatory political decisions.

Since the causal interpretation of policy effects rests on the untestable assumption of no unobserved confounders of the relation between citizens' reaction (M) and their feelings toward religious groups (Y), we conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the sensitivity of our results to this assumption (Imai et al., Reference Imai, Keele and Yamamoto2010a) and document it in the Supplementary material (see Figures S3 and S4). Here, it suffices to note that a violation of this assumption is unlikely to have major consequences for our main inference.

Our result also rests on the assumption that the causal order indeed runs from citizens' reaction to feelings and not the other way around, that is, in the sense that permitting a demonstration triggers a dislike of a group which then leads to a negative policy reaction. To bolster our causal claim, we rely on two observations.

First, we reverse our causal mediation analysis by treating feeling thermometer scores as mediators (M) and policy reaction as outcome (Y). We obtain a non-significant ACME of −0.02 [95 percent CI: −0.05, 0.01] and a significant but small ANDE of −0.08 [−0.15, −0.02]. In other words, the effect of authorities' permission of a demonstration on respondents' reaction is not mediated through feelings, but instead runs directly from permission to respondents' opposition.

Second, our causal perspective is supported by a classical experiment in the study of racial prejudice. In their famous “mere mention” experiment, Sniderman and Piazza (Reference Sniderman and Piazza1993) also relate policy preference to feelings toward a group (opposition to affirmative action and feelings toward Blacks). Crucially and unlike our experimental set-up they randomized the order between the policy question and the feeling question and found that raising the issue of affirmative action “was sufficient to excite a statistically significant response, demonstrating that dislike of particular racial policies can provoke dislike of blacks” (Sniderman and Piazza, Reference Sniderman and Piazza1993: 104, emphasis added).

7.2. Are Muslim immigrants affected more by backlash?

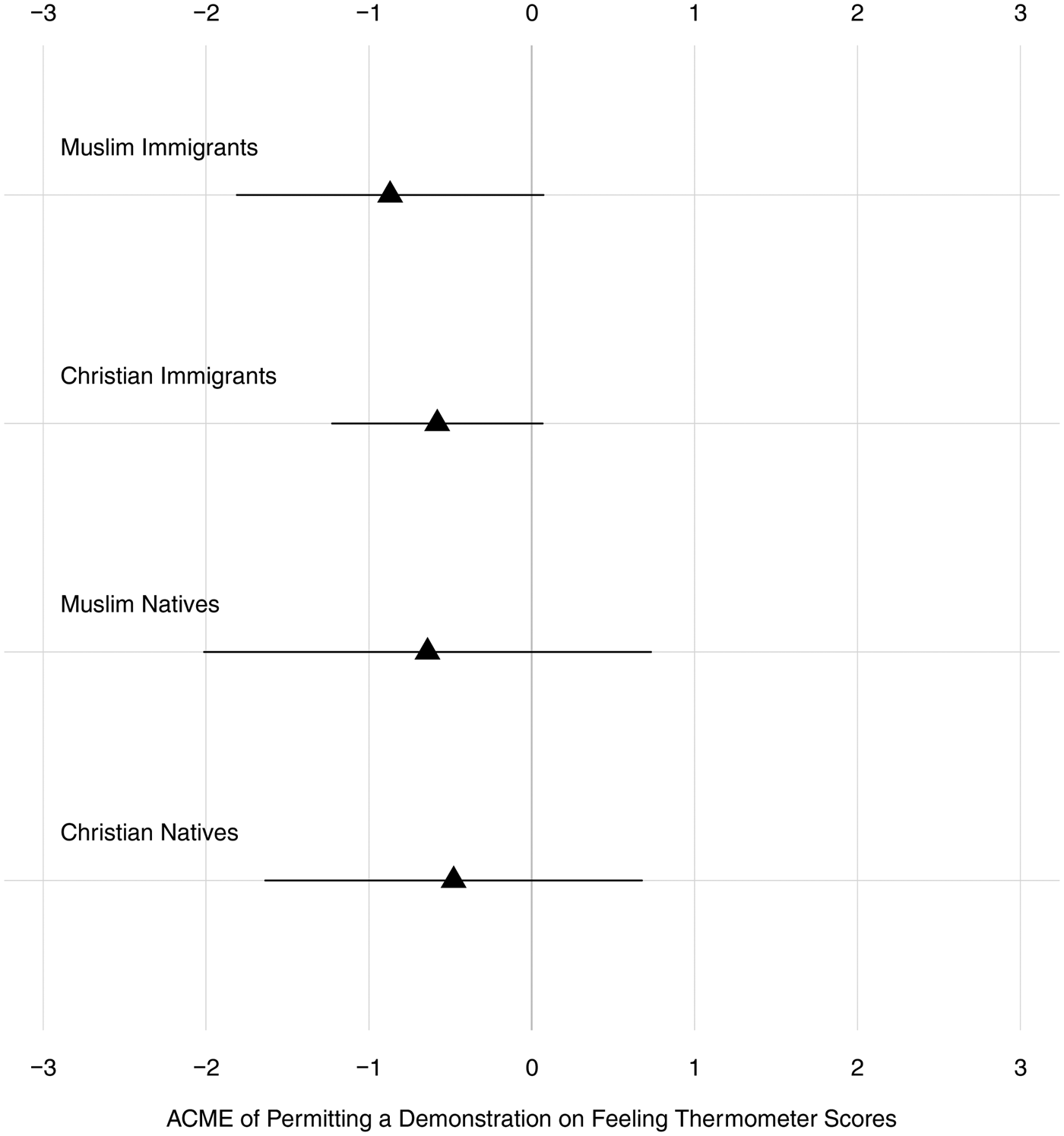

In this section, we demonstrate that the policy effect on citizens' feelings does not affect all groups the same way. Figure 3 presents the ACMEs of permitting demonstrations on the feelings toward four religious groups cross-classified by religious tradition and immigrant status. These estimates are based on regression models with additional multi-way interactions.

Figure 3. Causal mediation analysis of the effect of regulation on citizens' feelings toward four social groups cross-classified by religious tradition and immigrant status. ACMEs for treatment and control condition as well as average ACME reported along with 95 percent quasi-Bayesian CIs based on 1000 simulations.

In general, immigration status seems to matter more than religious tradition. Although there are no significant mediated policy effects on citizens' feelings toward UK natives, regardless of their religious identity, permitting demonstrations tends to produce cooler feelings toward immigrants—although by strict adherence to conventional standards this negative effect is not statistically significant for either Christian immigrants (average ACME: −0.58 [−1.23, 0.07]), or Muslim immigrants (average ACME: −0.87 [−1.81, 0.07]). Yet, this refines our previous result and suggests that citizens are especially critical of immigrants' public demonstrations and respond with greater dislike of this group when authorities decide to follow a permissive approach. As before, the substantive size of this policy effect is not very large but nonetheless visible.

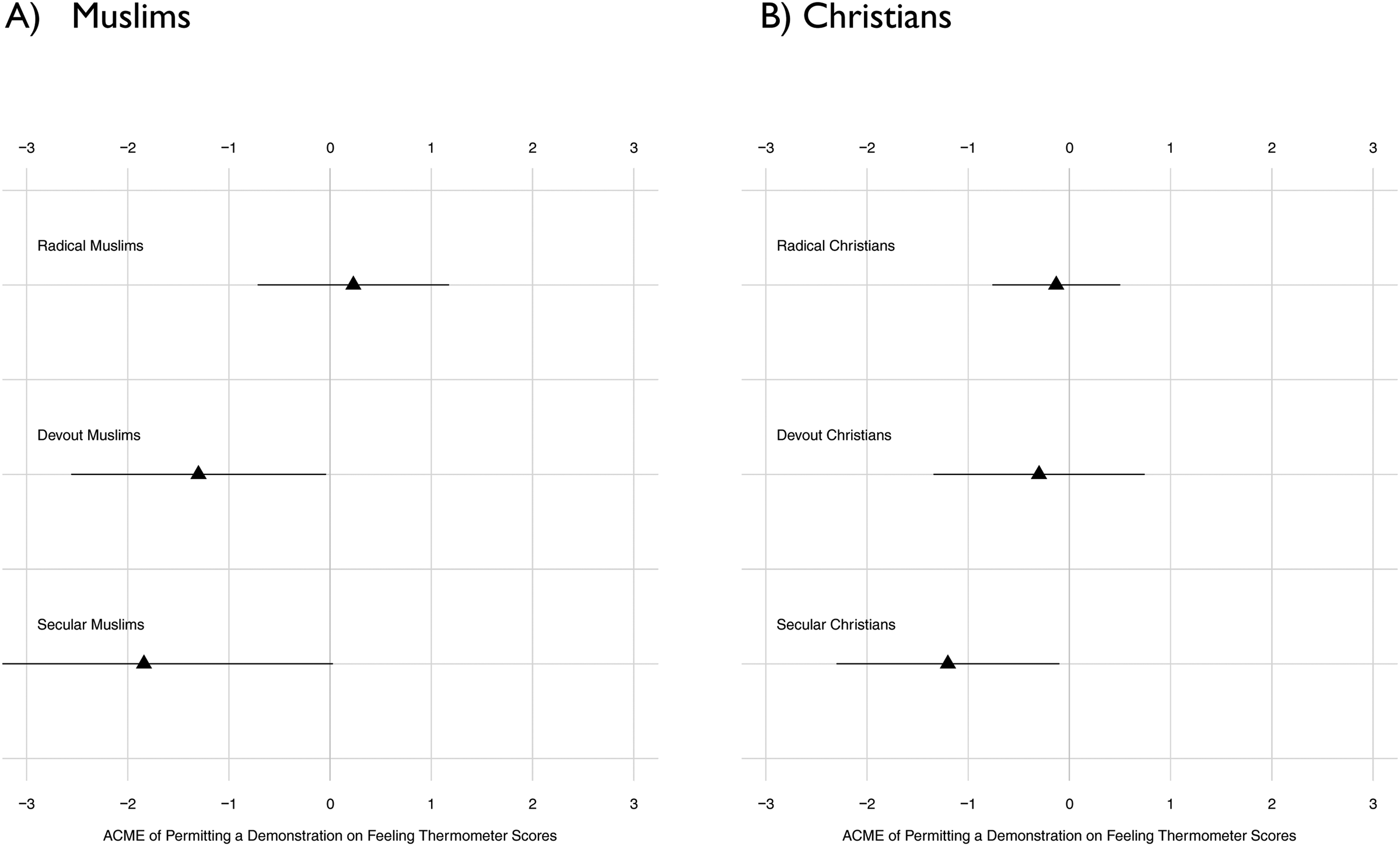

Next, we assess whether citizens’ reactions to permitting a demonstration differ depending on the nature of the demonstrators' religiosity, that is, whether the group is described as non-practicing, devout, or radical. Figure 4 illustrates how permissive regulations affect citizens' feelings toward social groups cross-classified by religious faith and type of religiosity.

Figure 4. Causal mediation analysis of the effect of regulation on citizens' feelings toward Muslim groups by type of religiosity. ACMEs for treatment and control condition as well as average ACME reported along with 95 percent quasi-Bayesian CIs based on 1000 simulations: (A) Muslims and (B) Christians.

The results suggest that, interestingly, moderate social groups are more affected by citizens' backlash than radical ones. In fact, we found no significant policy effect on the feelings toward radical Muslims or Christians. Along with the low feeling thermometer scores (reported in Table S3 in the Supplementary appendix) this hints at an unconditional rejection of religious radicalism, regardless of the policy approach adopted. However, permitting demonstrations leads to cooler feelings toward both secular Muslims and Christians. The average ACMEs are −1.84 [−3.70, 0.02] and −1.20 [−2.30, −0.10], respectively. Although respondents do not distinguish between secular groups, they react different to Muslim and Christian religiosity. Permitting demonstrations reduces feelings toward devout Muslims (−1.20 [−2.55, −0.05]) but not toward devout Christians (−0.30 [−1.34, 0.74]).

7.3. How citizens' reactions moderate the effect of policy on feelings

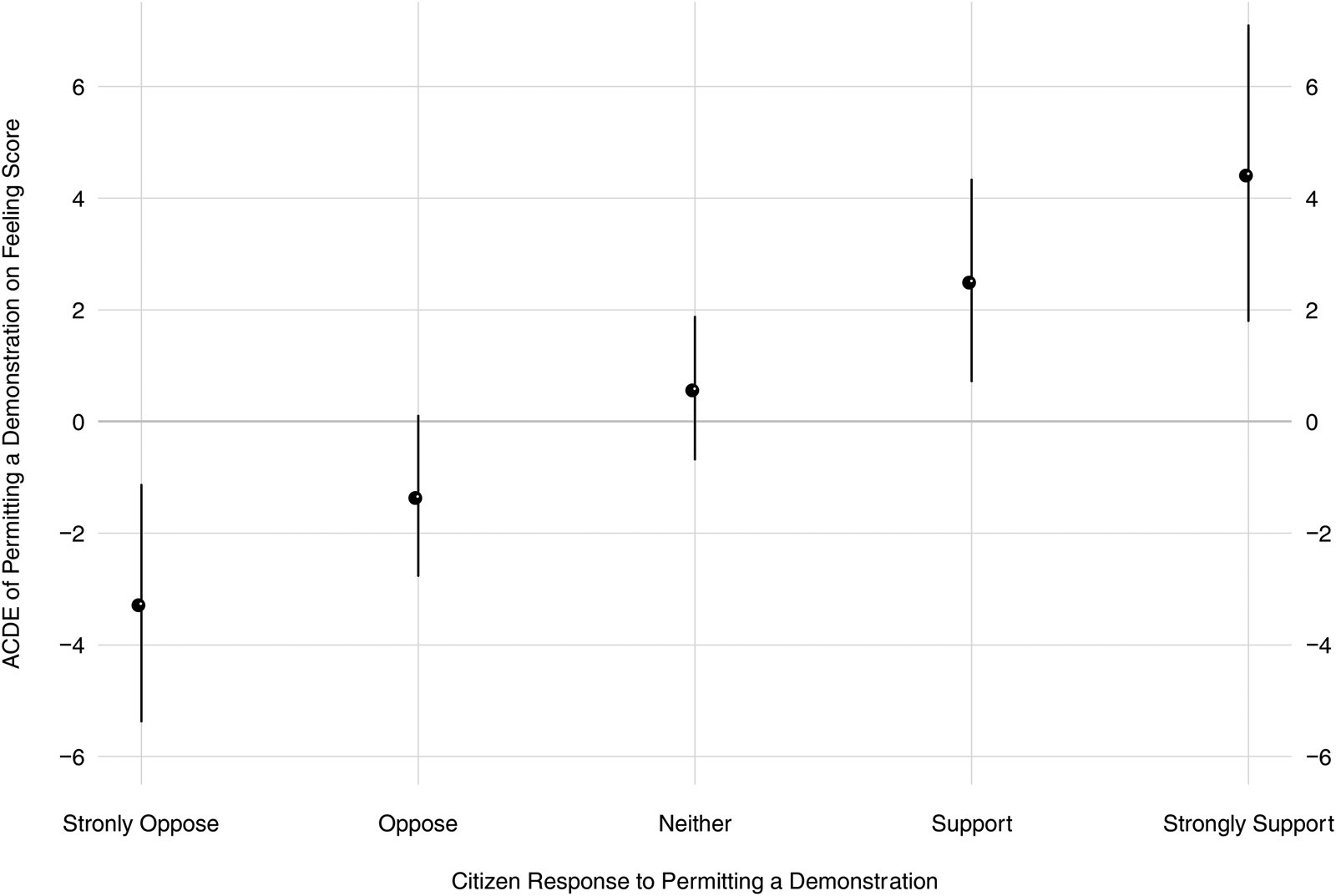

The central element of our backlash argument is that the effect of permitting demonstrations on feelings toward religious groups depends on citizens' policy preferences and thus results in a polarization. We now shed more light on this causal mechanism by taking a look at the ACDE presented in Figure 5. The ACDE illustrates how the effect of a policy is moderated by respondents' particular reaction to the authorities' decision, that is, their degree of support or opposition toward permitting a demonstration. This operationalizes our backlash argument.

Figure 5. How the effect of permitting demonstrations on feelings toward social groups depends on citizens' reactions. ACDEs based on model 2 in Supplementary material Table S5 with simulated 95 percent CIs.

Liberal respondents who support the right to demonstrate increase their warm feelings under liberal regulation. The respective ACDE is 2.53 [95 percent CI: 0.73, 4.33] for supporters of the policy and 4.45 [95 percent CI 1.80, 7.10] for strong supporters. Conversely, respondents who oppose a liberal policy decision reduce their warm feelings toward social groups permitted to demonstrate: by −1.33 [95 percent CI: −2.76, 0.10] for those opposed and −3.25 [95 percent CI: −5.37, −1.13] for those strongly opposed. For those in the indifferent we find no significant ACDE (0.60 [95 percent CI: −0.67, 1.87]). Thus, permitting demonstrations has completely opposite effects on the attitudes toward social groups, depending on whether citizens oppose or support the permission. Although the effect sizes on both sides of the polarization are roughly comparable, it is also instructive to consider the share of people on each side of the spectrum.Footnote 10 Supporters and opponents have equal population shares (20 versus 21 percent). But there are three times as many strong opponents (21 percent) than there are strong supporters (7 percent). Thus, the overall negative mediated impact reported before is due to the fact that considerably more citizens favor a restrictive approach—and liberal decisions by the authorities push even more people in this direction.

Since we rely on Stenner's (Reference Stenner2005) “authoritarian dynamic” to understand the psychological mechanism behind this polarizing backlash effect, a remaining question is whether citizens' policy reactions are indeed related to authoritarian dispositions. Although the experiment itself does not include measures of authoritarianism as potential moderating mediators it is possible to verify that respondents with authoritarian dispositions indeed react to the policy decision in predictable ways (i.e., support a ban and oppose a permit). Our survey includes three items that tap into authoritarian dispositions that were asked before the survey experiment.Footnote 11

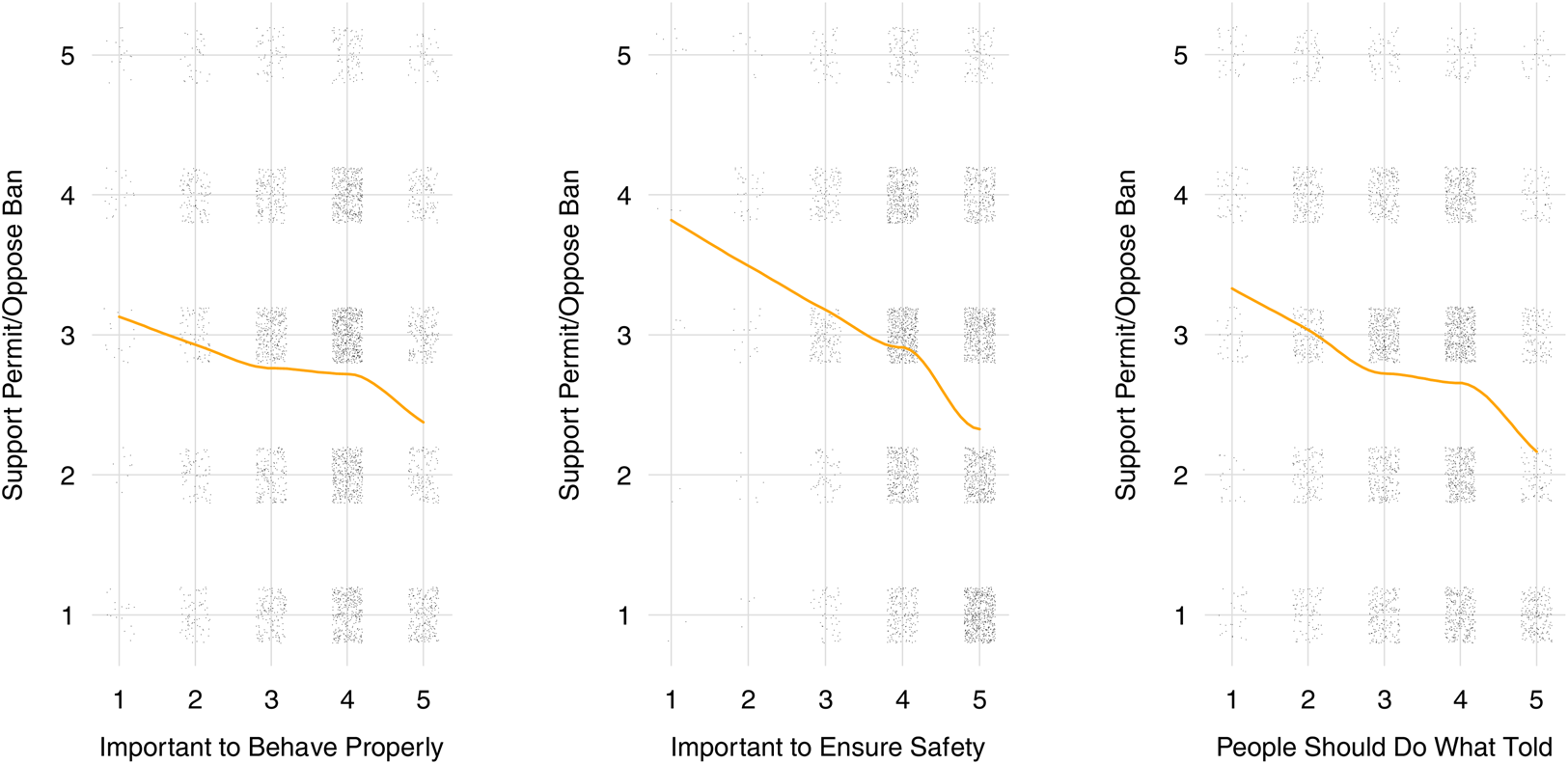

As Figure 6 shows, stronger agreement with these authoritarian ideas clearly correspond to lower support for permitting demonstrations or opposition to banning demonstrations. The correlation between supporting demonstrations and the view that one should always behave properly is −0.11 (p < 0.001), the view that government should ensure safety −0.25 (p < 0.001), and the view that people should do what they are told −0.19 (p < 0.001). The three items form a reasonable scale tapping into the same underlying authoritarian trait (Cronbach's α = 0.68) and a simple mean score is also significantly related to respondents' policy reaction (−0.23, p < 0.001). We interpret this as supporting evidence for our idea that respondents' policy reactions are indeed rooted in authoritarian dispositions which, when activated, lead to feelings of intolerance.

Figure 6. How the policy reactions relate to authoritarian dispositions. Jittered data with scatter plot smoother.

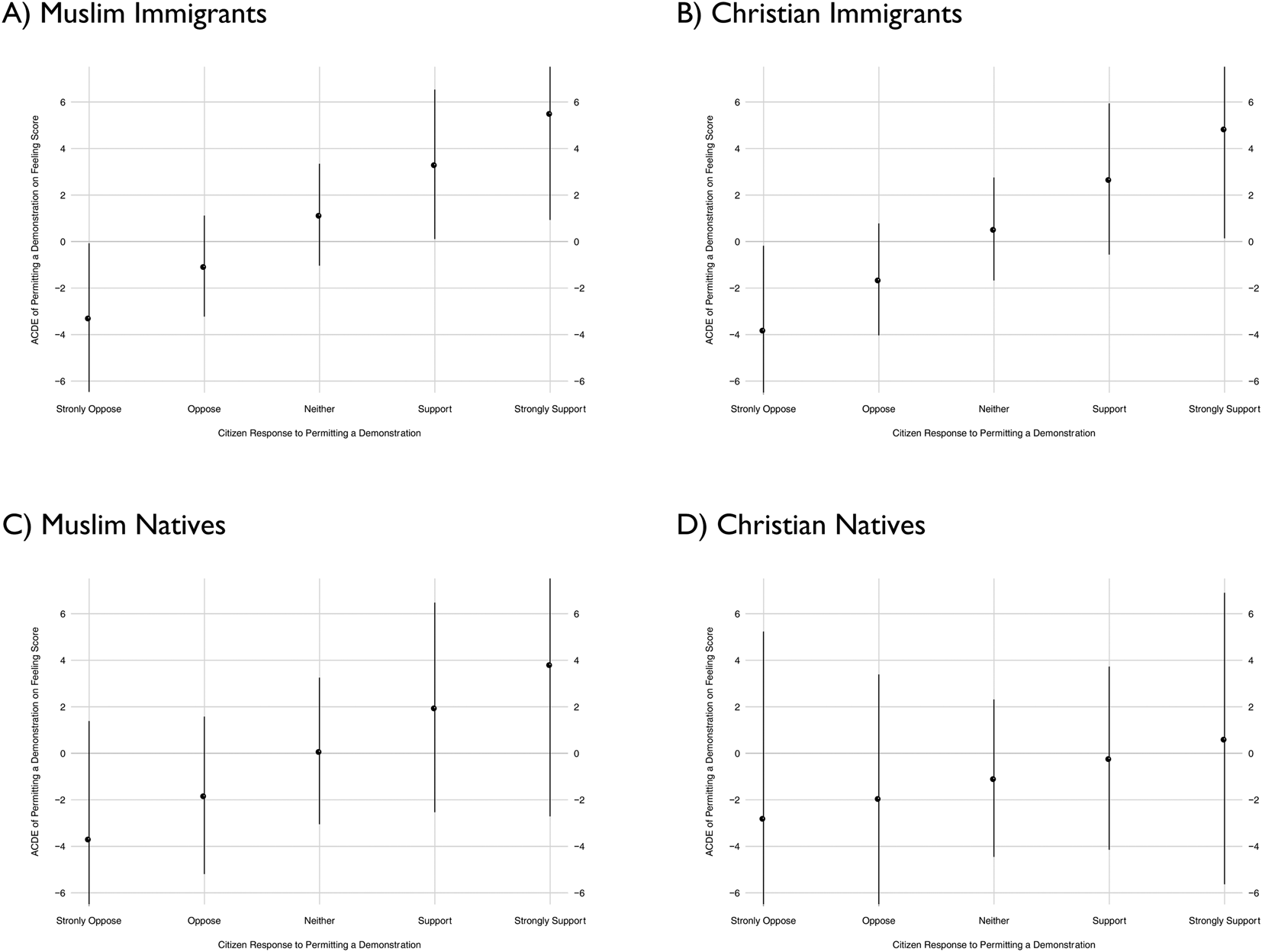

In the remainder, we again assess whether permitting demonstrations has comparable polarizing effects when different social groups are involved. As before, we find that permitting demonstrations for immigrants polarizes the public, but permitting demonstrations for natives does not (see Figure 7). And as before, respondents do not distinguish between Muslims and Christians. Permitting demonstrations of Muslim immigrants reduces the feelings of strong opponents by −3.27 [−6.45, −0.09] points on the feeling thermometer and increases them by 5.53 [0.94, 10.12] points for strong supporters. Permitting demonstrations of Christian immigrants reduces the feelings of strong opponents by −3.79 [−7.38, −0.20] and increases the feelings of strong supporters by 4.86 [0.16, 9.56] scale points.

Figure 7. The polarizing effect of permitting demonstrations for groups cross-classified by religious faith and immigrant status: (A) Muslim immigrants, (B) Christian immigrants, (C) Muslim natives, and (D) Christian natives.

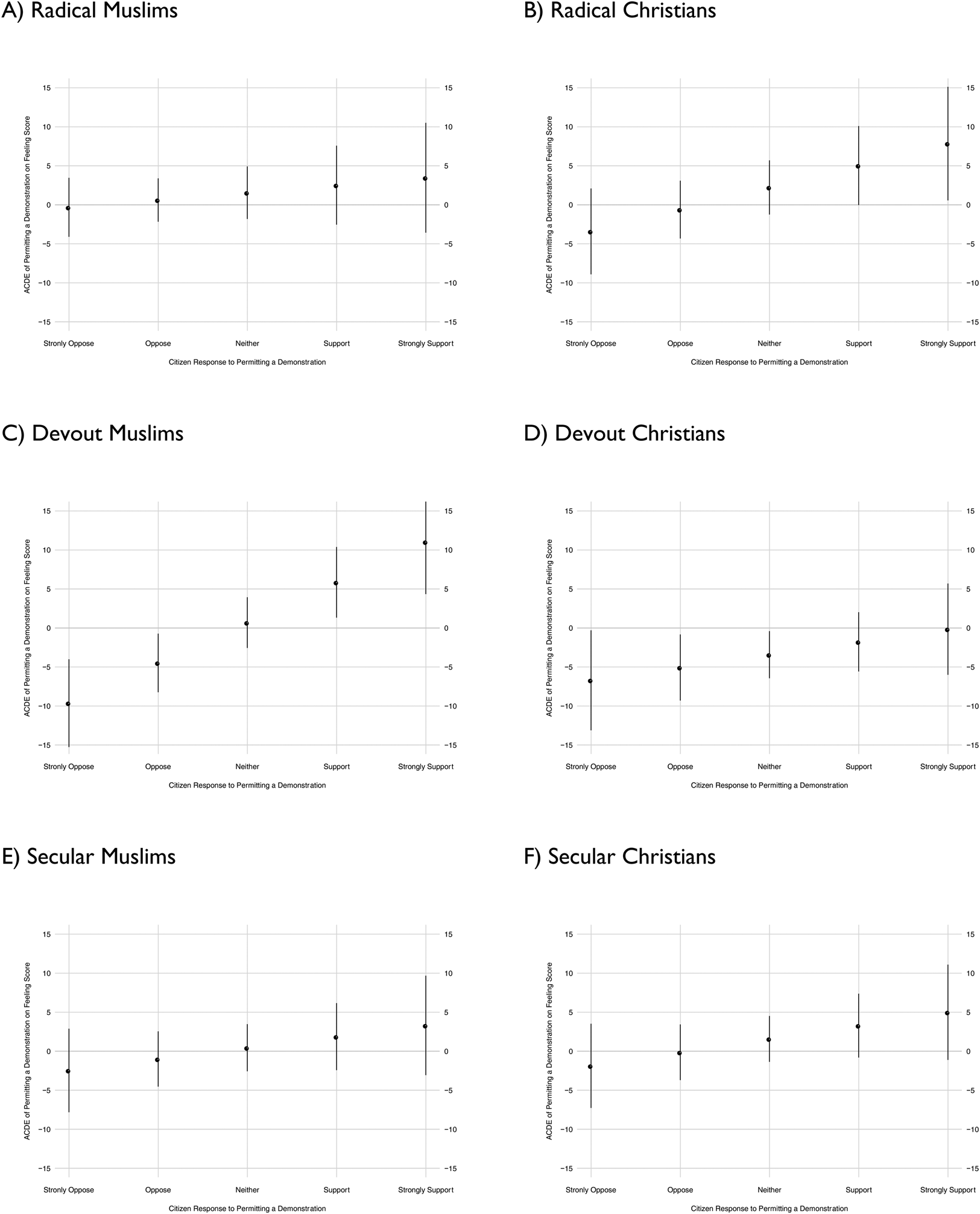

Separating groups of demonstrators according to their religious faith and type of religiosity (i.e., secular, devout, or radical, see Figure 8) reveals that permitting the demonstrations of two groups have the potential to polarize the public: devout Muslims and, to a somewhat lower degree, radical Christians. Clearly, the most pronounced polarization occurs for devout Muslims, where permitting demonstrations reduces the feeling scores of strong opponents by no less than −9.64 [−15.23, −4.05] points. On the other side of the polarization, it increases the sympathy of strong supporters by 11.02 [4.38, 17.66] scale points. For radical Christians, the effects on both sides of the spectrum are −3.42 [−8.89, 2.05] and 7.83 [0.60, 15.06], respectively. Permitting demonstrations for the remaining religious groups does not result in polarization.

Figure 8. The polarizing effect of permitting demonstrations for groups cross-classified by religious faith and type of religiosity: (A) radical Muslims, (B) radical Christians, (C) devout Muslims, (D) devout Christians, (E) secular Muslims, and (F) secular Christians.

8. Conclusion

Political conflicts over immigration, the public demands of immigrants, and their political rights have advanced to challenges in almost all Western democracies. In this paper, we have demonstrated that policy decisions can shape citizens' views on immigrants and their rights. Based on a survey experiment we were able to show that liberal policy decisions lead to a polarization in attitudes toward different groups of religious immigrants: Citizens who agree with a liberal policy decision become more sympathetic, while those in favor of a restrictive decision become more critical of immigrants.

This finding on opinion backlash to integration policy decisions has several important implications. It indicates that political elites face a considerable dilemma when regulating migrant integration. Even well-intentioned liberal policy may harm immigrants because it risks a backlash among more conservative citizens and increases opposition to the rights of this particular minority group. This insight qualifies previous research on the socialization effects of integration policy regimes in the explanation of citizens' attitudes toward minorities which suggests that liberal policy regimes which grant wide ranging political and cultural rights will make citizens more tolerant (Weldon, Reference Weldon2006; Wright, Reference Wright2011; Schlueter et al., Reference Schlueter, Meuleman and Davidov2013).

Our findings call this optimistic view into question and suggest that—at least in the short run—integration policy is not the subject of a shared consensus among citizens, but one of polarization. Citizens are not simply socialized into an integration regime. Instead, they form their opinion toward immigrants in a critical response to the regulatory approaches suggested by political actors. Policies that threaten the status quo are rejected by many and result in counter-productive outcomes in the sense that some citizens are less likely to accept immigrants and their political demands. This seems to limit the strategic options of political actors who, by devising liberal policy, not only risk losing citizens' electoral support but also failing their intended policy goal.

It would be wrong to conclude that yielding to the intolerance of some and restricting immigrants' political rights could be seen as a viable solution to this dilemma. Apart from being problematic on normative grounds, restricting the rights of immigrants or creating a hostile environment may itself lead to a reactive effect, expressed in higher rates of traditional or even radical religiosity as well as lower willingness to adapt to or to identify with the values of the host society (Foner and Alba, Reference Foner and Alba2008; Connor, Reference Connor2010; Voas and Fleischmann, Reference Voas and Fleischmann2012; Carol and Koopmans, Reference Carol and Koopmans2013). This way, a “discriminatory equilibrium” (Adida et al., Reference Adida, Laitin and Valfort2014) is maintained where immigrants experience discrimination and are reluctant to assimilate, whereas members of the majority identify the lack of assimilation and express a distaste for immigrants.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2020.44.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the EPSA annual meetings 2016 and 2018 and invited talks at the Cologne Center for Comparative Politics, Goethe University Frankfurt and Social Science Research Center Berlin. We thank the audiences at these events, Anselm Hager, Andrew Hall, Melanie Kolbe, Moritz Marbach, the PSRM editors, and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions and feedback. Keigo Tanabe provided excellent assistance in the final replication process. Full replication materials can be found at the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NHSJMJ. Special thanks go to Robert Ford, Marcel Coenders, Anouk Kootstra, and Menno van Setten for allowing us to include our survey experiment in their panel study.

Financial support

This research has been partly funded by the German Research Foundation (Grant numbers HE 6182/5-1 and TR 1334/3-1).