Introduction

In 2015, the fishing town of Havøysund on the northwestern coast of Finnmark, Norway, got its first Sámi tourism company. The entrepreneurs behind Arctic View (Arktisk utsikt) were Reidun Mortensen and Aslak Henrik Lango. The core of their venture was a high-quality restaurant that they opened in a small modernist concrete house located 5 km from the town centre, on Mount Havøygavlen. The house was built in 2005, on the edge of the cliffs on the outer side of the mountain. The site and architecture provided an excellent view from the new restaurant to the nearby fishing grounds, and the horizon of the Arctic Ocean. A more peculiar feature was Arctic View’s location on the margins of a wind power plant. The production of wind energy had started at Havøygavlen in 2003, and it was the old construction road that enabled visitors to travel to the new restaurant, and the furthest wind turbine supplied it with electricity. Any tourism entrepreneur would probably value the view offered by the location highly, despite the wind turbines. The morphology of Havøygavlen may even remind visitors of the iconic North Cape tourist destination, which is located slightly further along the coast, close to Honningsvåg town. Arctic View and Havøysund are, however, “off the beaten track” of tourism. The first years of Reidun and Aslak’s venture were characterised by great challenges as well as exciting and enriching experiences. Unexpected setbacks awaited, however, and today, Arctic View is closed. The reconstruction of the wind power plant made it impossible to maintain the business for the two years that the work took. Controversies surrounding the situation have left Reidun and Aslak dubious about the situation and highly uncertain about their future as tourism entrepreneurs in Havøysund.

Within the context of pre-pandemic tourism growth in the Norwegian Arctic, both Sámi and Norwegian governmental institutions had expectations that the communities of Finnmark and Sápmi, the area traditionally inhabited by the Sámi people, would engage more strongly in the tourism economy. In 2018, and right before the reconstruction of the wind power plant was announced, Reidun and Aslak became our main cooperative partners in a research project on Sámi entrepreneurship in tourism. The research aimed to contribute with knowledge that could illuminate the conditions of the current indigenous tourism ventures in Sápmi, based on qualitative cooperative studies of the on-ground experiences of Sámi entrepreneurs. The research process led to a study of Reidun and Aslak’s entrepreneurship, which enabled the current paper’s explorations.

At destination management level, tourism in Sápmi has so far not been “a matter of indigenous control” (Müller & Viken, Reference Müller, Viken, Viken and Müller2017, p. 4), and the extensive use of Sámi culture in destination marketing controlled by non-Sámi has meant that Sámi people are “used to sell destinations” (Müller & Hoppstadius, Reference Müller, Hoppstadius, Viken and Müller2017, p. 74). Despite this, Sámi people in Norway and Sweden have had relatively strong control as entrepreneurs in Sámi tourism, when compared to Finland and Russia. Several research projects have engaged in the co-creation of knowledge about Sámi tourism with indigenous entrepreneurs (see, e.g. Höckert, Kugapi, & Lüthje, Reference Höckert, Kugapi, Lüthje, Harju-Myllyaho and Jutila2021; Kramvig & Førde, Reference Kramvig and Førde2020).

The main body of previous research on Sámi tourism has focused on the development of indigenous tourism “…beyond the economic” (Bunten & Graburn, Reference Bunten, Graburn, Graburn and Bunten2018, p. 1) and emphasised matters of identity politics and representations (Viken, Reference Viken2006). This research has unfolded within prolonged research on communities, regional development and a wider range of Sámi issues (see, e.g. Baglo, Reference Baglo2017; Kramvig, Reference Kramvig, Viken and Müller2017; Olsen, Reference Olsen2002, Reference Olsen2003, Reference Olsen2006; Pashkevich & Keskitalo, Reference Pashkevich and Keskitalo2017; Pettersson, Reference Pettersson2004; Saarinen, Reference Saarinen and Ringer1999; Tuulentie, Reference Tuulentie2006, Reference Tuulentie, Viken and Müller2017; Müller & Viken, Reference Müller, Viken, Viken and Müller2017; Wright, Reference Wright2018). In line with studies of indigeneity on other continents (Bunten & Graburn, Reference Bunten, Graburn, Graburn and Bunten2018), investigations have focused on tourist–indigenous “host” interactions and discussed representations and communication along the lines of topics well known from the international research literature on indigeneity and tourism. The topics range from commodification, tourism imaginaries, and the indigenous “other” (see, e.g. Mathisen, Reference Mathisen2020; Niskala & Ridanpää, Reference Niskala and Ridanpää2016; Olsen, 2002, Reference Olsen2006; Wright, Reference Wright2018), boundary making (Schilar & Keskitalo, Reference Schilar and Keskitalo2018), and indigenous spirituality (Fonneland, Reference Fonneland2012), to storytelling (Kramvig & Førde, Reference Kramvig and Førde2020), the care and protection of Sámi cultures (Saari, Höckert, Lüthje, Kugapi & Mazzullo, Reference Saari, Höckert, Lüthje, Kugapi and Mazzullo2020), and governance issues (Angell, Nygaard & Selle, Reference Angell, Nygaard and Selle2020; Pashkevich, Stjernström & Lundmark, Reference Pashkevich, Stjernström and Lundmark2015). Hence, and while focusing more on explicit and unambiguous indigenous topics in Sámi tourism, the research literature has attended less to the way that indigenous identities, meanings and material practices imprint more discreetly on the steps taken by indigenous entrepreneurs when starting and developing tourism ventures in Sápmi, which is the aim of this paper. Such knowledge is relevant for illuminating what may be at stake as Sámi people become agents in Arctic destinations.

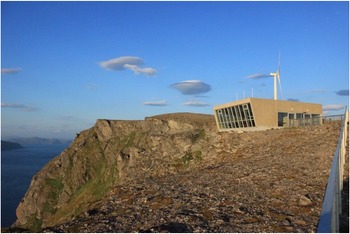

This paper attends to Sámi people who engage as entrepreneurs in tourism in Norwegian parts of Sápmi. We suggest ways to identify when and how indigeneity emerges as a topic and meaning dimension that makes a difference in the entrepreneurship process, before we discuss how indigeneity can mark the process in ambiguous ways. The exploration is based on a detailed account of Reidun and Aslak’s Arctic View venture in Havøysund (see Fig. 1). The rich description makes up “a story against which researchers can compare their experiences and gain (…) insights” (Dyer & Wilkins, Reference Dyer and Wilkins1991, p. 613), based on attentiveness to “the context in which events occur” (Ibid., p. 615) and the valuing of narrated context-dependent knowledge in “the collective process of knowledge accumulation” (Flyvbjerg, Reference Flyvbjerg2006, p. 227).

Fig. 1. Arctic View, on the edge of the cliffs of the mountain Havøygavlen, 5 km from Havøysund centre. Photo and copyright: Aslak Henrik Lango.

The paper attends to the entrepreneurship as part of Reidun and Aslak’s life stories, everyday life and material practices (Thompson, Verduijn, & Gartner, Reference Thompson, Verduijn and Gartner2020, p. 2479) and focuses on the intrinsic geographies and histories (Massey, Reference Massey1994, Reference Massey2005) to which their various relational practices connect the enterprise. The analytical narrative sensitises (Atkinson, Reference Atkinson2015) power-relevant historical-geographical continuities and transformations on this basis and considers the part played by indigenous tourism entrepreneurship in such processes. The approach accentuates how “…in the activities of the entrepreneur we may recognise processes which are fundamental to questions of social stability and change…” (Barth, Reference Barth and Barth1972, p. 4) and demonstrates how indigeneity may turn a tourism entrepreneurship into a matter of cultural endurance within processes of becoming (Clifford, Reference Clifford2013; Kraft, Tafjord, Longkumer, Alles, & Johnson, Reference Kraft, Tafjord, Longkumer, Alles, Johnson, Kraft, Tafjord, Longkumer, Alles and Johnson2020).

The historical-geographical approach relies on a spatial ontology (Massey, Reference Massey1994, Reference Massey2005) through which we pursue temporal-spatial relations that become part of the entrepreneurship through Reidun and Aslak’s undertakings. The relationships with places and times to which different encounters and interactions connect the entrepreneurship enable us to trace the wider geography and history that, step by step, become entangled in the remoulding of the venture’s space. It is within these geographical and historical relational processes that we identify emerging indigenous trajectories and discuss how they are assembled (c.f. Tsing, Reference Tsing2015), or are thrown together (Massey, Reference Massey2005) in the entrepreneurship space, and become part of its making.

At the same time, and in line with the spatial ontology, we understand places as continually reconstituted through diverse trajectories that meet up and intersect in them (Massey, Reference Massey1994, Reference Massey2005, Reference Massey2007). Places are thus dynamic patchworks of power relations involving negotiations – whether formal or informal, discreet or open – about what and who the place is for (Granås, Reference Granås, Viken and Granås2014). Negotiations over place happen within a wider history and geography than accounted for by the here-and-now of a place. When approaching their future, Reidun and Aslak relate to the people, places and practices of the past that sometimes mean that Sáminess surfaces in the venture, as well as in the venture’s places. In such processes, indigenous meanings appear as contingent relational after-effects of history, like a “history of the present” (Comaroff & Comaroff, Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2009, p. 38). In this way, we consider Sámi entrepreneurships in tourism in light of the unstable and changing ethnic qualities of places, while acknowledging the current transformative complexities of indigeneity (Clifford, Reference Clifford2013, p. 13) that the relational undertakings of Reidun and Aslak entail.

The study’s focus on people’s practices (Ortner, Reference Ortner2006) recognises that human relational practices sometimes imply engagements with more-than-human bodies and materialities. We consider how the venture itself, as well as the places it is part of, become with (Haraway, Reference Haraway2008) floras and faunas (Haraway, Reference Haraway2003, Reference Haraway2008; Palsson, Reference Palsson, Ingold and Palsson2013; Tsing, Reference Tsing2014), technologies, bodies (Haraway, Reference Haraway1991, Reference Haraway2003, Reference Haraway2008), and physical place qualities (Hinchliffe, Reference Hinchliffe, Featherstone and Painter2013). This view enriches the analysis by accounting for the difference that more-than-human “partners” in people’s relational practices make, based on the inherent material-semiotic capacities and time-spatial connections of such relational partners. The approach allows us to consider a similarly wider range of indigenously potent trajectories that become part of shaping the entrepreneurship space. Altogether, the materially condensed narration of the entrepreneurship considers, for example, wind, wildlife, mountains and houses, not as exogenous factors, but as part of the entrepreneurship process, where their material, semiotic and relational qualities sometimes make a difference. When pursuing a general request for geographical sensitivity in research on Sámi tourism (Müller & Viken, Reference Müller, Viken, Viken and Müller2017, p. xv), the historical-geographical approach and the more-than-human perspective helps us to situate discussions in the particular geographies and material histories of Northern Europe (Ren, Jóhannesson, Kramvig, Pashkevich & Höckert, Reference Ren, Jóhannesson, Kramvig, Pashkevich and Höckert2021).

The research process

The dialogue between Reidun, Aslak and the two university researchers who authored this paper began in April 2018. One of the authors and Reidun had already cooperated in a development project in Havøysund, without knowing each other well. All four of us live in the north and were born here, and we were connected through partly overlapping social networks in Finnmark before this study started. Since we began working together in 2018, we have met three times in Havøysund. Our meetings during these visits took place in Reidun and Aslak’s home, at the municipal hall, at the local hotel and at Arctic View. We have also been together in meetings with the municipality, the Arctic Wind energy company, the local association of tourism businesses and the research project group of which this study is part. Along the way, we have also communicated regularly by phone and through Microsoft Teams and met several times at the university campus.

The original plan to meet “in the field” during the writing phase was hindered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, we have had three online meetings of 2 to 3 hours length, based on draft versions of the paper. We discussed and elaborated the analysis together in these meetings, while ensuring that the story of the paper is one where the four of us share ownership. Traces of the dialogical writing process are sometimes explicitly noticeable in terms of the comments by Reidun and Aslak that appear throughout the analysis. The dialogue has provided a rich space for an abductive research process (Alvesson & Sköldberg, Reference Alvesson and Sköldberg2009) where theoretical resources have been (re)visited and new possibilities explored regarding how to provide depth to the analysis.

This way of working connects to a growing discourse on co-creation in research. The discourse encompasses many aspects (Ren van der Duim & Jóhannessonh, Reference Ren, van der Duim, Jóhannesson, Ren, van der Duim and Jóhannesson2017). Our application of a co-creating methodology relies on an interactionist and performative understanding of research (see, e.g. Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Coffey, Gubrium and Holstein2003; Järvinen & Mik-Meyer, Reference Järvinen, Mik-Meyer, Järvinen and Mik-Meyer2005) that sees data from observations, interviews and conversations as situational knowledge produced through interaction. Inspired by Gunnar Þór Jóhannesson, Lund, and Ren (Reference Jóhannesson, Lund, Ren, Ren, van der Duim and Jóhannesson2017), our aim has been to be open and seek out varying relational situations of knowledge production, using a flexible research process (Vannini, Reference Vannini2015). The closing of Arctic View, together with the pandemic lockdown, however, hindered our further opportunities to meet on different arenas and experience different situations together. In general, the process has nevertheless nurtured the authors’ understanding of co-creation as a way of embracing the potential for relational ethical knowledge in research co-creation. As Maria Puig de la Bellacasa (Reference Puig de la Bellacasa2012) argues, caring and thinking is relational. The co-creative methodology was decisive for our access to emerging indigenous meanings in Reidun and Aslak’s story, as the subject itself calls for dialogue over time within relations of mutual respect, trust and care (Puig de la Bellacasa, Reference Puig de la Bellacasa2012).

Our interest in indigenous emergences and our processual approach to entrepreneurships, places and indigeneity relies on “…the indispensable moral and analytical value of the micro, the singular and partial…” (Biehl & Locke, Reference Biehl, Locke, Biehl and Locke2017, p. xi). This approach acknowledges the “world-historical significance” of specificity (Biehl & Locke, Reference Biehl, Locke, Biehl and Locke2017, pp. 11–12) and values that of attending to the many small generic moments (Kapferer, Reference Kapferer, Meinert and Kapferer2015) of an entrepreneurship process like the one studied here. Based on this methodology, and in line with the logics of the classic case study method, the analysis prioritises deep understanding and contextual insight before comparative insight (Dyer & Wilkins, Reference Dyer and Wilkins1991, pp. 613–614; see also Torrance, Reference Torrance, Somekh and Lewin2005, and Stake, Reference Stake, Denzin and Lincoln2005).

The outcome of our approach is an analysis that encompasses many moments and aspects of the entrepreneurship studied. As we enter the analysis, we hold back explicit references to the main theoretical perspective while allowing for Reidun and Aslak’s story to be told (cf. Dyers & Wilkins, Reference Dyer and Wilkins1991) in a way that is nevertheless analytical and marked by the perspectives described above.

Considering a tourism venture

Reidun and Aslak decided to move to the coast and start Arctic View in 2014. Since then, their home and “central station” have been Reidun’s childhood home in Havøysund, a post-war house (etterkrigshus) in the town centre, built according to the typical architecture of post-war Finnmark and Northern Troms. Reidun’s family moved here from the coastal Sámi settlement Burstad at the end of the 1960s, when Reidun was a toddler. This was then her home until she finished school and left the town 30 years ago. Rather unexpectedly, and due to family circumstances, the house became vacant in 2013. This was also the year when, momentously enough, Aslak left reindeer herding. His background is the Sámi reindeer herding community in Finnmark and its main base in the interior of the county. His year of birth meant that the Norwegian government’s Reindeer Husbandry Act of 1978 left him without the right to make a living from his reinmerke (traditional reindeer brand). In 2013, Aslak had realised for a while that he could not make enough money from reindeer herding. Therefore, he and Reidun now worked fully with a reindeer meat distribution company that he had started up three years earlier to supplement his income. By naming the company Fjellfinngutt (mountain finn boy), he gave a post-colonial twist to the term finn, a (previously) derogatory word for Sámi.

Earlier in his life, Aslak had worked for several years as a hotel receptionist in Finnmark and for the Norwegian Armed Forces. Reidun had studied at university, and then worked for a seafood company in the south of Norway and abroad. When she and Aslak became a couple, she decided to move back to Finnmark. The two agreed to live together på fjellet (at the mountain), says Aslak, so that Reidun could get to know his life as a reindeer herder. Aslak’s “mountain” includes the landscapes that stretche from his siida’s (i.e. the group of reindeer owners with whom he has performed his reindeer herding) winter pastures in interior Finnmark to their summer pastures on the coast, not too far away from Måsøy municipality and Havøysund.

As Reidun’s family home became vacant, another house in Havøysund, Arctic View, had become available. Strangely enough, this house had materialised as a consequence of the Arctic Wind wind power plant, which began production at Havøygavlen in 2003. The plant was the first of its kind in Troms and Finnmark and was known as “the world’s northernmost wind power plant.” Arctic Wind’s economy was based on green certificate trading in an interconnected European energy market. Nuon, a Dutch energy company, constructed the plant together with Norsk Hydro and Norsk Miljøkraft. As part of a deal with the community, they built Arctic View in 2005 and gave it to Måsøy Municipality. Several people ran different dining concepts there in the following years. As Reidun’s childhood home turned the couple’s attention towards Havøysund, the vacant Arctic View and the mountain Havøygavlen interrupted their Fjellfinngutt venture and på fjellet life and inspired an idea to instead make a future together on the coast of Sápmi.

Reidun and Aslak started seeing a potential for high-end tourism based on Sámi values in the skinny tourism landscape of Havøysund and Måsøy. They understood the semiotics of wind turbines as somehow acceptable in their idea, considering that wind power was known as green energy and that the construction period was finished years ago. Also, when at Arctic View, visitors’ eyes are drawn towards the Arctic Ocean, and no wind turbines can be seen through the windows. They soon concluded that a high-quality restaurant based on Sámi values should be the start of their venture here. The restaurant would be the first of its kind and the first tourism initiative in Måsøy to be profiled as Sámi.

Part of the consideration phase involved Reidun and Aslak’s awareness of Havøygavlen’s resemblances to the North Cape in the neighbouring municipality. Havøygavlen seemed to be a potentially more “exclusive” version of the North Cape, which, with its large visitor centre and around 250 000 guests every year, had been a strong tourist attraction in Northern Norway for more than a century (Jacobsen, Reference Jacobsen1997; Tiffany, Reference Tiffany1884). They had also witnessed the recent general growth in Arctic tourism (Müller, Reference Müller, Carson, de la Barre, Granås, Jóhannesson, Øyen, Rantala, Saarinen, Salmela, Tervo-Kankare and Welling2015; Stewart, Draper, & Johnston, Reference Stewart, Draper and Johnston2005) that has marked several places in Finnmark (Müller et al., Reference Müller, Evengård, Nymand Larsen and Paasche2020). Nevertheless, and partly due to physical geography and infrastructure, Måsøy had so far been disconnected from the main tourism streams of the region. Around 1000 inhabitants live in houses in Måsøy’s municipal centre, closely packed around a harbour. Extensive fishing industry constructions speak of fisheries as a pillar for the area’s culture and economy. Tourism here had so far evolved in the shadows, with fishing tourism as the main activity. Reidun and Aslak were excited to add something new to the tourism landscape while pursuing “the good life” on the coast, as Reidun puts it.

Entangled in historical-geographical politics of indigenous loss

As they took their very first steps towards moulding the space of their entrepreneurship, Reidun and Aslak engaged with various human and more-than-human partners. Materialities in terms of houses, mountains and non-human-animals “impinge on the subject” and both encouraged and constrained their possibilities (Biehl & Locke, Reference Biehl, Locke, Biehl and Locke2017, p. 6). Together with their human partners, such materialities connected the entrepreneurship to the time–space relationships that we will track in the following. We will also start considering the role of entrepreneurship in Sápmi place processes, starting from Aslak’s reindeer, and the relationships to which the reindeer connected the entrepreneurship.

In many ways, the venture was a consequence of Aslak being one of many reindeer herders who could no longer herd reindeers (Müller & Hoppstadius, Reference Müller, Hoppstadius, Viken and Müller2017, p. 72). For him, this is a disappointing outcome of state regulations that handed him the wrong cards in life. Reindeer herding in Norway is performed in ethnically fluid and manifold landscapes. The practice itself is nevertheless defined as Sámi and reserved for Sámi people. Modern-day reindeer herding is not controlled by Sámi institutions alone, but managed by the Norwegian government, and is mainly within the competence of the Ministry of Agriculture. In recent decades, indigenous peoples around the world have argued for the right to “repatriate” not only cultural artefacts and knowledge but also land and resources (Castree, Reference Castree2004, p. 136). All these elements are pursued in Sámi politics. Notably, and importantly in a sensitising of Sámi geographies of today, the idea of repatriating Sápmi in terms of claiming “…full control of land…” (Castree, Reference Castree2004, p. 137) is not an outspoken claim from Sámi people. Sápmi is even more marked by current sovereignty discourses within which “patterns of belonging (…) accentuate sovereignty without secession” (Maaka & Fleras, Reference Maaka, Fleras, Ivision, Patton and Sanders2000, p. 108). Reidun claims that the repatriation of Sápmi is considered taboo as a subject, which reminds us that to cast someone or something as indigenous is never an innocent act, but “assertions of priority and ownership [that] are always claims to power” (Clifford, Reference Clifford2013, p. 14).

More specific rights to make use of landscapes and their many assets and affordances, for example, for land-intensive reindeer herding, is explicitly contested in places within Sápmi today. This is a contested history-in-the-present (Comaroff & Comaroff, Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2009, p. 38) which includes different historically connected experiences of loss among today’s multi-ethnic inhabitants of the area. Aslak’s departure from reindeer herding, which was directly bound to a sensitive history of governmental policies regarding reindeer herding, exemplifies such a loss. For Aslak, the loss concerns his indigenous identity and is thus of existential proportions and hard to “leave behind.” Ultimately, this tourism entrepreneur is still a reindeer herder.

Other relationships activated in the venture’s start-up can be traced through Reidun’s childhood home. As with Aslak’s departure from reindeer herding, it is hard to imagine their entrepreneurship without the relationships to which their new home on the coast connects them. By the end of WW2, the occupying German power had forced the inhabitants of Northern Troms and Finnmark to evacuate, before burning down practically all towns and villages. The house in Havøysund was raised during the rebuilding in the late 1940s and 1950s. Although material–cultural ties to the past had been cut during the burning, modernisation now materialised abruptly in people’s homes.

Reidun’s family decided to move to Havøysund years after Burstad as well as Havøysund had been rebuilt. Their move from Burstad was driven by centralisation, which was another aspect of post-war state policy. The state offered her parents 30 000 NOK to move, Reidun says. At this point, it took her father 4 h to take his children to school by boat. Her parents had fought for a road connection to ensure that Burstad could keep up with the modernisation processes in the region. Now, they gave up the battle. The state’s centralisation politics per se were “blind” to ethnicity. The family, however, moved from a Sámi community to a Norwegian town in-the-making. The Sámi language was definitely lost for Reidun, who was one-year-old at the time. These days, she wonders what it was like for her father, the fisherman. Altogether, the ethnically dispassionate centralisation politics of this period implied the weighing of ethnic anchors in place, practices, knowledges and ways of life for many coastal Sámi. For Reidun, this geographical history entails emotional relationships with indigenous value, both within her family and to the place they left behind before she was old enough to remember life there herself. As Reidun and Aslak’s life in Havøysund and tourism venture unfolded, different relational practices entangled them with this convoluted history of disruptions.

Practicing natural resource periphery through tourism: conflicting interests in Sápmi

Tourism-wise, Reidun and Aslak’s start-up in Havøysund by no means came “out of the blue.” The idea to work with tourism had grown upon them during a range of previous life experiences and reflections (Tuulentie, Reference Tuulentie2006). The potential they ascribed to the place of their venture was bound to topical tourism considerations when relating it to other places in the area (cf. Massey, Reference Massey2004), not least to the North Cape. Their initiative also followed in the wake of the recent decade’s governmental politics to promote tourism as a potentially important economy in the peripheries (Hujibens & Jóhannesson, Reference Hujibens and Jóhannesson2019; Müller & Viken, Reference Müller, Viken, Viken and Müller2017, p. 4). In Norway, the government used tourism as a tool with which to strengthen the particular economy and culture of Sápmi (Kramvig, Reference Kramvig, Viken and Müller2017; Müller & Viken, Reference Müller, Viken, Viken and Müller2017) entailed in the periphery geography of the north.

The Norwegian state, however, makes use of a wider repertoire than tourism in its continual practicing of the high north as a natural resource periphery. The wind turbines at Havøygavlen are a materialisation of a state repertoire that has been dominated by capitalist-based modernist industry initiatives within fisheries, mineral extraction and energy production. Such initiatives are regularly caught up in place processes. Towns and villages have been exposed to industrialisation since long before WW2, and layers of centre–periphery power relations have marked their development. Throughout the post-war era, new technologies and recent neoliberal policies have intensified extractive processes and changed economic conditions for local communities. Inhabitants have experienced ever-reduced access to fishing, and communities have been left with ever-fewer economic gains. Delimited local benefits also haunt the more recent wind power production and fish farming. This development is an important backdrop for understanding the depopulation suffered by Havøysund and other coastal communities in the area after the rebuilding period. Places have been left vulnerable in encounters with external investors who approach the area with new natural resource-based industrial projects. The importance of such centre–periphery relations is acknowledged by many inhabitants. This geographical relationship is asymmetrical, and one of dependency; and thus, the local space may be limited as regards critical opposition to the “central powers” who want to intervene and invest there. Reidun and Aslak are among those who nevertheless may raise their voices against modernist industry politics and question how forward-looking they actually are and what overall value they have for life in the north.

Tourism development in the Arctic must be understood in relation to “…the areas’ history and presence as resource peripheries” (Müller & Viken, Reference Müller, Viken, Viken and Müller2017, p. 5). Tourism relies on similar geographical understandings of the area – as an exotified wilderness – as, for example, extractive industries (Herva, Varnajot, & Pashkevich, Reference Herva, Varnajot and Pashkevich2020; Granås, Reference Granås2018). Reidun and Aslak’s entrepreneurship, and places like Havøysund and Sápmi of which it is part, are entangled in globalising neoliberalism through different natural resource periphery economies. These include tourism and energy production. This does not necessarily imply that the indigenous and multi-ethnic places and entrepreneurships of the periphery are victims at “the loser’s end” of geographical relationships. Rather, a venture like the one explored here takes part in and makes use of “the multidirectional, unrepresentable sum of material and cultural relationships” of globalisation, and the “places and people, distant and nearby” to which they are connected (Clifford, Reference Clifford2013, p. 6).

The area’s periphery status may be a double-edged sword for its many small-scale tourism entrepreneurs. While it spurs the government to suggest that tourism is developed, governmental expectations seem to be based on a new-colonial and capitalist rationale. Not to anticipate the events of Reidun and Aslak’s story, this rationale does not reflect the workings of small-scale tourism and may leave entrepreneurs vulnerable in situations of conflicting interests in place – as different economies intersect in place (Massey, Reference Massey2005), frictions follow (Tsing, Reference Tsing2005). For entrepreneurs like Reidun and Aslak, the conflicting interests between different industries in Sápmi connect to a troublesome past and to the uncertainties of making a life and a living as a Sámi in the future.

Unfolding

The modernist architecture of Arctic View by no means suggests that it is located in Sápmi. When Reidun and Aslak began their business, they themselves conversely brought a small selection of items into the house that displayed prominent Sámi symbols. Among them were the well-known Sámi souvenirs found in the glass showcase by the entrance, some of which were made by Aslak’s mother. Pieces of reindeer antlers are made into table decorations, together with stones and heather, and reindeer furs hang over some of the chairs. A reindeer makes up the centre of the company’s logo. Guests are welcomed in Sámi with the words Buorre beaivi (hi/good morning) written on the chalk board by the kitchen.

When it comes to food experiences, the principle of Arctic View has been to serve reindeer as the only meat, and then base the menu on other local ingredients, such as cod and other seafood, and herbs, berries and the like. The restaurant had a head start in its first year, when they were asked to host a dinner for Norway’s King and Queen. Local products on the Royal Menu of June 2015 ranged from cod fish, reindeer and king crab, to different berries, herbs and seaweed gathered in the area. Neither Reidun nor Aslak are trained chefs, but they both have extensive experience from earlier work with food production, including dealing with the bureaucracy of food safety regulations from Mattilsynet (the Norwegian Food Safety Authority). Notably, they are both “foodies,” with a pronounced culinary sense. These are all resources that, when activated in their networking, enabled them to cooperate with professional chefs in the time to come.

From the very start, the two worked to integrate Arctic View into the community life. They hosted special dining events during the local festival Havøysundagan and Norway’s National Day and organised concerts and other cultural events, often without any particular Sámi theme. All the activities took place during the summer season, which is when Arctic View is accessible. As with many small-scale experience providers in tourism, Reidun and Aslak soon saw the need to develop an accommodation concept, to allow long-distance travellers to stay longer and thereby keep their head above water business-wise. At the same time, they were eager to expand their indigenous performance space. Their next step was thus a glamping concept at Havøygavlen, using the lávvu, the traditional Sámi temporal dwelling. Both before and during their venture, Aslak sometimes organised excursions på fjellet for smaller tourist groups on request, where he has tested and developed ideas about how to introduce tourists to his culture. Glamping provided possibilities for working further with such ideas at Havøygavlen, not least by inviting tourists into a mode of sensing the world while being in the landscape, “in rhythm with nature” and “with watches put aside,” Aslak explains.

The venture gradually matured. Inspired by customer feedback and enthusiastic tourists in particular, the two entrepreneurs came up with ever more ideas about how to advance their business, including how Arctic View could be used during the winter, despite the hard and unpredictable weather conditions. As a pilot project, they hosted an overnight stay for a newlywed couple at Arctic View during the winter. The couple spent the night in a lavvu put up indoors, laced with its opening directed towards the windows, and thus a view of the ocean and the northern lights. Other ideas included taking tourists to Burstad and cooperating with reindeer herders who had their pastures in Måsøy.

When they moved to Havøysund in 2014, they took different paths into the community. Reidun was already considered a “local.” She had only embraced her Sámi identity after becoming an adult, so the newest thing about her was mainly that she now presented herself as Sámi. Her commitments to regional and economic development prompted her to join local politics upon her return. These commitments come with a devotion to environmental issues that she herself understands as the Sámi heritage from her parents who had instilled into her the values of being varsom (cautious) with nature. Her political engagement soon took an unexpected turn. Sadly, the elected mayor fell sick in the middle of the election period. As she represented the mayor’s party on the municipal board, Reidun was encouraged to step up. Two years into their venture, she found herself the political leader of Måsøy. One of the many things she did as mayor was to initiate the municipality’s first public celebration of Samefolkets dag (the day of the Sámi people/Sámi National Day) in 2017.

Since Aslak belonged to a siida that has its summer pastures in the neighbouring municipality, he was already familiar with the coastal landscape when he moved to Havøysund. Further back in time, his family had their summer pastures in Måsøy. This explains why one of his grandfathers is buried in the town. Aslak believes that the inhabitants’ awareness of his ancestors’ place affiliations may have given him a certain degree of legitimacy upon arrival. He was still conscious about not “putting on his kofta” (Sámi costume) and “bandying around” in it, he explained to us after a meeting in the local association of tourism businesses. This was his response when we discussed the support he had gained for his ideas about branding Måsøy as a slow-tourism high-end destination. Aslak was involved early in the celebration of Samefolkets dag, mainly through meeting school children and discussing Sámi issues with them. He speaks warmly of this experience. Later in our cooperation, however, he described his position in the community as increasingly difficult. At one point, he mentioned that he had been asked by inhabitants where he thinks he “actually comes from” (egentlig kommer fra). Reidun is very familiar with the question, and they agree that its connotations are disturbing. Still, she insists that she would never be confronted with it by people in her home town.

Aslak’s problematising of his position came at a time when their tourism venture had run aground, and, after a turbulent election campaign in 2019, Reidun’s party had lost and she was no longer mayor. In 2018, energy production had challenged their venture and “good life” at the coast in highly problematic ways, as they were informed that the wind power plant was to be renovated. This meant that the old wind turbines would be replaced by new and bigger ones, with a construction period of two years. Reidun had disqualified herself as mayor from any municipal dealings with Arctic View. Soon, Aslak took the lead in the process of negotiating solutions, while Reidun was manoeuvring through a growing political storm at the municipal hall. An important consideration for Aslak was to ensure that their new brand would survive the two years without losing its value, and the market position it carefully was about to gain. The main negotiating partners were the current owner of Arctic Wind and the municipality, which still owned Arctic View as a building. Many ideas were discussed. Ultimately, and after two years of intensive and difficult negotiations, no deal was made. The renovation of Arctic Wind began in 2020. The electricity supply from the wind turbines to Arctic View was cut off, and the road at Havøygavlen was closed.

Indigenous performances of places in Sápmi

Guided by an interest in the entrepreneurship’s inseparability from performances of everyday lives (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Verduijn and Gartner2020, p. 247) in places (Massey, Reference Massey1994, Reference Massey2005), the next step will be to look into Reidun and Aslak’s wider engagements in the local community. This starts with their first public celebration of Samefolkets dag in the town in 2017, which was 25 years after the Sámi Congress had decided that Sápmi should be celebrated on February 6 every year. The Congress had set the date according to the opening of the very first Sámi Congress in 1917. In 2017, the flag of Sápmi had been officially recognised for more than 30 years, and Samefolkets dag had become a well-established anniversary in the Norwegian parts of Sápmi, but not everywhere. The late first celebration in Havøysund mirrors the fluid ethnic status of many of Sápmi’s places. The town exemplifies the places that cannot be assessed as “Sámi only” and where Norwegians are often in the majority (Pettersson & Viken, Reference Pettersson, Viken, Butler and Hinch2007; Schilar & Keskitalo, Reference Schilar and Keskitalo2018). The ethnic status of places is not only about numbers, but also it concerns historical relations that affect how ethnicity is understood (Comaroff & Comaroff, Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2009, p. 38). It is thus connected to a history of northern Europe that describes indigenous–non-indigenous relationships that sometimes differ from the North American settler history narration (Keskitalo, Reference Keskitalo, Hansson and Norberg2009; Thuen, Reference Thuen2012). Notably, ethnic and colonial histories in Sápmi are place-specific, and many settlements were multi-ethnic before the time of modern colonialism, and some had been so since pre-historic times. Within this ethnically multi-layered northern European geography, Sápmi has emerged as a politically acknowledged and institutionally consolidated level during the last 40 years. The contested about this geography tends to come to life in discussions about how Sámi is a specific town or village. Notably, the two entrepreneurs were engaged in a place that was weakly associated with Sápmi at that point. With Arctic View and Samefolkets dag, they initiated two moves that stood out in the ways they asserted its Sámi identity.

Aslak’s comment about not “bandying around” in his kofta speaks of a wariness in place, and being asked “where one is actually from” confirms this uneasiness. The question relates to a history to which today’s inhabitants around Sápmi may refer, which is very old, and, through archaeological remains, takes us back to the first humans present here after the last glacial period. Public discussions may surface about who they and later arriving groups were, and where they came from. These discussions are fuelled by interpretations of pre-history based on current ideas about ethnicity and indigeneity. Sámi people may thus be wary in place and discomforted when asked where they are actually from. The question breathes life into, and also attacks, the power-laden idea that people who are acknowledged as indigenous today have priority in a specific place (cf. Clifford, Reference Clifford2013). No matter what, their indigenous status is challenged. While indigeneity may not be radically questioned in Norwegian mainstream politics, such notions do circulate, and may surface in local politics around Sápmi, as also experienced by Reidun and Aslak. The suspense about the indigenous practicing of places that their story reflects is important regarding the “bad feeling” that one risks provoking when undertaking an indigenous entrepreneurship in Sápmi today. Indigenous entrepreneurships call for attention within local communities where “…both clear-cut and hybrid identity categories (…) co-exist” (Thuen, Reference Thuen2012, pp. 240–241). Ethnic identity may not be a black-or-white matter or mean that much at all for inhabitants.

It was new for Aslak to be part of the Sámi minority of a small town like this. Where he is from, the Sámi are in majority. As with his ancestors, his affiliations with the coast had until now been based on nomadic reindeer herding. To live here permanently and be a tourism entrepreneur was indeed something new and something that disrupted the traditional time-spatial directions for when a reindeer herding Sámi was expected to be present where in Sápmi, and do what. Within this tradition, the social institution called verdde is known to organise interactions between the coastal and the reindeer herding Sámi. Some have suggested translating verdde as “a helping friend” and explained the term’s traditional denotation as “…the mutual beneficial and social connection between the reindeer herders and the settled residents…” (Svensson & Viken Reference Svensson, Viken, Viken and Müller2017, p. 261) along the coast. When reflecting on his increasing difficulties in Havøysund, Aslak claimed that verdde is important, but that here, people have forgotten about it or ignore it. When referring to verdde, he gropes for a social organisation that could have better supported his indigenous presence in place, based on the fact that he still considers himself a reindeer herder. Today, and without reindeer but with a tourism business, such a position as a member of Sápmi (Magga, Reference Magga, Brantenberg, Hansen and Minde1993, p. 87) may nevertheless be out of reach. Aslak admits that it seems to him that the verdde institution lies fallow on this particular part of the coast these days.

This takes us to the hybrid histories and geographies of the Norwegianisation of Sápmi. As documented by Harald Eidheim (Reference Eidheim1966), verdde has been pressured and transformed for a long time, due to Norwegianisation and modernisation politics. The fact that Aslak’s mother tongue is Northern Sámi reflects that the core areas of the reindeer herding communities are where the Sámi language has stood strongest during the many years of governmental measures to assimilate and hence Norwegianise the Sámi people. Reidun’s history, however, connects the entrepreneurship and its place to the young Norwegian nation’s assimilation politics that, reinforced by modernisation, ran effectually on the more multi-ethnic and multi-lingual coast from the 1800s (Eidheim, Reference Eidheim1966, Reference Eidheim and Barth1969, Reference Eidheim and Barth1972; Eythórsson, Reference Eythórsson2008; Hermansen & Olsen, Reference Hermansen and Olsen2020; Olsen, Reference Olsen2006; Pain, Reference Pain1960). As argued by Trond Thuen (Reference Thuen2012), part of the assimilation of Sámi people on the coast can be explained by “the experience of belonging to the same class of peasants/fishers [that] weakened the significance of the ethnic border (Thuen, Reference Thuen2012, p. 240). Eidheim, on the other hand, described how coastal Sámi people in the 1950s and 1960s “navigated their ethnic expressions within a highly stigmatised environment” (Hernes, Reference Hernes2017, p. 32). In this period, the majority of the coastal Sámi lost their language (Eidheim, Reference Eidheim and Barth1969; Hermansen & Olsen, Reference Hermansen and Olsen2020; Pain, Reference Pain1960). If we compare the number of inhabitants who consider themselves Sámi today with those accounted for in the 1900 Norwegian population census (Eythórsson, Reference Eythórsson2008) in many of the coastal municipalities, the reduction is striking. Måsøy is one example: in 1900, which was a long way into the Norwegianisation process, 580 inhabitants (33%) were registered as Sámi. The number of inhabitants (above the age of 18 years) enlisted as members of Samemanntallet (with a right to vote at Sámediggi) in 2008 was, however, less than 80 (7%) (Eythórsson, Reference Eythórsson2008, p. 21; Sámediggi 2022). These numbers primarily indicate that in the wake of Norwegianisation, this is an area where few inhabitants have so far reclaimed the Sámi identity that their kinship prepares them for. It should however be noted that there are no indications that the general depopulation along the coast affects the relative number of inhabitants who present themselves publicly as Sámi.

Reidun’s reappearance in the town as a Sámi is potentially contested in its own specific ways. Her taking back of her Sámi identity as a grown up is part of a collective history of Sámi resistance and revitalisation that manifests itself in place through her embodied presence. The Sámi Congress in 1917, mentioned earlier, indicates a long history of political mobilisation to promote the affairs of Sápmi. As the consequences of the state’s previous Norwegianisation measures continued to affect Sápmi long after WW2, the counter-movement and resistance rose to new levels. It had considerable effects, with the establishment of Sámediggi (the Sámi Parliament of Norway) in 1989 and Norway’s ratification of the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples (ILO) Convention in 1990 as two important milestones. Particularly since the 1980s, Sámi revitalisation has made northern Norway “more Sámi.” Indigenous revitalisation, however, progresses differently in different places. Reidun’s life history was once again interwoven with her home town. Through who she was now and her consequent participation in local politics and in tourism at the same time, she found herself on the front line of the town’s revitalisation as Sámi.

Sápmi remakings

The architecture of Arctic View is of a kind that you would not be surprised to encounter at any continent. Inspired by Doreen Massey’s place theory (Massey, Reference Massey1994, Reference Massey2005), the house can be seen as a material-semiotic (cf. Haraway, Reference Haraway1991) manifestation of the diverse globally situated realities of the place we are in, as constituted through tourism, as well as fisheries, power production and much more. The large windows anchor and stage indoor experiences in the specific landscape where it is located. At the same time, the architecture encourages re-interpretations through the perspectives on, and relationships to, the landscape that it provides. Reidun and Aslak’s high-quality restaurant based on local ingredients utilised the potential of working as a team with this assemblage of material partners in place (cf. Tsing, Reference Tsing2015, p. 292). The straightforward modernist building became a place where they could improvise their involvement with people, food, heritage and landscape. They could do so together with well-known Sámi souvenirs that comprise “symbols of distinction” in tourism (Bunten & Graburn Reference Bunten, Graburn, Graburn and Bunten2018, p. 8) and in ethno-politics (Kramvig, Reference Kramvig, Forbord, Kvam and Rønningen2012). Even more so, they could set out without heavy material constructions that predetermined their dealings with ethnicity and the many different livelihoods of Sápmi in the past and present that connect to the entrepreneurship space, both through their life stories and through the place processes of which the venture is part.

At Reidun and Aslak’s Arctic View restaurant, reindeer has so far been the only meat on the menu. Even though it can be served at any restaurant in Fennoscandia, it is the only one of the principle ingredients on the menu that is widely acknowledged as Sámi. Aslak anchors reindeer meat in Sámi knowledge and traditions through his role as chief buyer and cultural translator for the professional chefs that prepare it. The reindeer that is served also has a central place in the Sámi iconography that dominates in tourism, and which ultimately builds first and foremost on preconceptions about a traditional reindeer herding culture (Olsen, Reference Olsen2003; Wright, Reference Wright2018). Other Sámi livelihoods in the past and present have not added similarly to this iconography. This includes the material culture of the coastal Sámi, which once upon a time was based on fishing within combined livelihoods, primarily in combination with small-scale livestock farming (Eythórsson, Reference Eythórsson2008). In the 1960s, Eidheim commented on a “lack of ‘contrasting cultural traits’” (Eidheim, Reference Eidheim and Barth1969, p. 40) between coastal Sámi and Norwegians. Notably, he described this lack as “conspicuous” (Eidheim, Reference Eidheim and Barth1969, p. 40). Today, the cultural traits of coastal Sámi are still not easy to distinguish. Reidun and Aslak, however, express no worries about that.

Cod fish and wild salmon are the main types of saltwater fish served at Arctic View. The saltwater fish entangles in the entrepreneurship as a local resource. This fish is, however, important for the venture in the way it connects to the coastal Sámi and moulds the entrepreneurship’s indigenous space in relation to this material culture. At the same time, saltwater fish ties the restaurant to the highly “Norwegian” fishing town of Havøysund and supports the restaurant’s foothold there. In the post-war era, cod became a well-established gem in the iconography of “North-Norwegianness.” By making cod central to their indigenous menu, Reidun and Aslak re-contextualise it and reclaim the cod as indigenous, and in accordance with a traditional coastal Sámi scheme. The cod thus re-becomes Sámi after a period of Norwegianisation. Notably, they make the cod Sámi also, as opposed to reclaiming this iconic fish as Sámi only, which is a claim that has been made by others (Hansen, Reference Hansen2019). The same is true of the wild salmon on their menu, a delicacy along the coast that however has a vaguer ethnic iconic status. Today, wild salmon are at risk and displaced by farmed salmon in the fjords along the coast. Reidun and Aslak buy their wild salmon from local fishermen who, be they Sámi or Norwegian, have maintained their knowledge about wild salmon fishing throughout modernity.

Similarly, Reidun and Aslak encourage us discreetly to understand the fishing culture of Havøysund as multi-ethnic. Instead of making power claims to priority in place (cf. Clifford, Reference Clifford2013), they appear as “life experimenters…” who are capable of changing their own and other people’s thinking in contingent ways, without being “…knowable ahead of time” (Biehl & Locke, Reference Biehl, Locke, Biehl and Locke2017, p. 7). Within the assemblage at Arctic View, where the architecture allows the fishing grounds in, and where “local” is a principle, the entrepreneurs re-enact a coastal Sámi culture with deep roots in rich and profound ways. In doing so, they include emblematic elements from the reindeer herding culture, such as well-known souvenirs, lavvus, reindeer meat and reindeer antlers, in processes where indigeneity come to life.

In these entrepreneurial undertakings, different livelihoods in Sápmi in past and present are brought together rather than being practiced as distinct. The indigenous becomings of the venture “occupies its own kind of temporality that unfolds in the present: a dynamic interpenetration of past and future” (Biehl & Locke, Reference Biehl, Locke, Biehl and Locke2017, p. 6). At the same time, they allow for indigeneity to be enacted together with non-Sámi, such as the Danish chef who worked there when this study was beginning. Over the years, Reidun and Aslak have explored the local fauna and flora together with different chefs, in search of new culinary expressions. The entrepreneurship thus engages in revitalisations of Sápmi in novel ways and has the potential for nuancing emblematic understandings of Sámi culture, in and through tourism.

For Reidun and Aslak, the Arctic View venture is somewhere they can help indigeneity survive, through combined performances and the emerging indigeneity they may bring (Clifford, Reference Clifford2013, p. 85). In doing so, they “…reproduce tropes of indigeneity while opening pathways for emergent and creative expressions of identity…” (Bunten & Graburn, Reference Bunten, Graburn, Graburn and Bunten2018, p. 10). In his elaborations on the survival and struggle of indigenous peoples throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Clifford speaks to our entrepreneurs when stating that:

But many have held on, adapting and combining the remnants of an interrupted way of life. They reach back selectively to deeply rooted, adaptive traditions: creating new pathways in a complex postmodernity. Cultural endurance is a process of becoming. (Clifford, Reference Clifford2013, p. 7).

Sáminess in Reidun and Aslak’s endeavour becomes “neither a monolithic ‘thing’ nor (…) an analytic construct,” but “a loose repertoire of signs by means of which relations are constructed and communicated” (Comaroff & Comaroff, Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2009, p. 38). We suggest to see the sum of their different moves as discreet non-strategic enactments of the multi-ethnic geographies of Sápmi, within which reconciling undertones are heard (cf. Kramvig & Førde, Reference Kramvig and Førde2020).

Do we allow for unhappy endings?

Arctic View is now closed. Reidun is still active in local and regional politics. Otherwise, she is unemployed. Aslak however works as a fisherman. When they closed Arctic View, an old man in Havøysund contacted him and invited him to join him fishing on his small smack. Aslak later took over the boat, and these days, he goes fishing in the fjords of Måsøy together with the old man’s son. Reidun and Aslak are not sure whether they can re-start their tourism business when the reconstruction of the wind power plant is complete. Their overall experience is that their life here as entrepreneurs has been paved with local political adversities. They also worry that some of the adversities may be encumbered with suspicion towards them as indigenous people.

By describing multi-layered northern geographies and histories, we have indicated the challenges that, regardless of ethnicity, come with being a small tourism entrepreneur in place negotiations in the natural resource periphery. Critiques of modernist industrial projects in the area risk being understood as “against development,” and hence against the well-being of an already marginalised community. At times, Aslak’s demands in the negotiations with the power company had implied potential economic expences and costly delays for the power company. Ultimately, he obstructed what local political forces saw as a more important development project for the municipality. Reidun’s political arguments for environmental issues and securing local benefits in industry development had the potential to add to this understanding. In this context of the natural resource periphery place, the tourism entrepreneurs altogether felt that their negotiating partners lacked understanding and respect for a small-scale tourism entrepreneurship.

The history of Reidun and Aslak, however, also speaks of an entrepreneurship space that takes shape in connection with indigenous losses and Sámi revitalisation. Their presence in place and the moves they made implied enactments of Havøysund as Sámi, and their venture has left traces of novel performances of Sápmi. This story provides glimpses of hope, reconciliation and vital remakings of Sápmi. Nevertheless, the entrepreneurship process indicates that northern environments involve stigmatisation of indigenous people and demands for careful navigations of ethnic expressions. It is this latter aspect that twists the adversities of an entrepreneurship into a matter of Sáminess at risk in place.

Reidun asked if unhappy endings are allowed in studies like this. The question is intriguing for the current analysis. It is not only a call for recognition of their unhappiness about the potential end of a tourism venture but also a call to acknowledge the unhappiness about an entrepreneurship process that is inseparable from indigenous life itself. Framed as a question, Reidun’s appeal was made with an awareness of how indigenous discomfort tends to be rejected – why not let the past be the past? Recently, the Norwegian government has nevertheless recognised formally that the indigenous past is important for the future: the government now notes that the Sámi people of the north have been particularly marginalised and suppressed throughout modernity, as have the Kven/Norwegian Finn minority. At the time of the current study, this politics of recognition is expressed in the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The commission is set to investigate the Norwegianisation policy and to lay the groundwork for the recognition of the experiences of the Sámi and Kvens/Norwegian Finns during enforcement of this policy, based on investigations of “what consequences these experiences have had for them as groups and individuals” (The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2022). The government thus altogether indicates that personal, emotional and existential indigenous experiences have political relevance.

Reidun also appealed to us to include emotions in the study. Even though the subject calls for further investigations, we would like to comment on it by the end of this paper. Sara Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2002) has described how emotions should not be isolated in the private sphere and then potentially pathologised. Emotions must be considered in light of their social relational scope. Thinking back on, for example, Aslak’s loss as a reindeer herder, this is an experience that clings to him. It becomes part of accumulated experiences (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2002) throughout life and throughout the Arctic View venture. The loss surfaces over time, as an accumulated experience of pain with indigenous meaning. This is also a way of reading Aslak’s descriptions of how he feels haunted in life – his own life and his family’s work life have been revisited by modernist industrial interventions in Sápmi: Aslak himself had to leave reindeer herding due to land use pressure and land management that delimited his space as a reindeer herder. He then had to leave tourism because of wind power. Meanwhile, he has helped his brothers, who were protesting against a new mining project, to secure their pastures. Now he is a fjord fisher, and the fishing grounds are threatened by the same mining project, as well as by fish farming. This process of accumulated experiences of land use contestations with indigenous meanings may explain why, as noted by Müller and Hoppstadius (Reference Müller, Hoppstadius, Viken and Müller2017), Sámi tourism entrepreneurs who are not involved in such contestations with their business still emphasise land use interests as a major challenge (Müller & Hoppstadius, Reference Müller, Hoppstadius, Viken and Müller2017, p. 81).

“Unfinishedness is both precondition and product of becoming,” João Biehl and Peter Locke claim (Reference Biehl, Locke, Biehl and Locke2017, p. x). If Sápmi is one and many places, if places are becoming, and if indigeneity is becoming within processes of endurance, (Clifford, Reference Clifford2013) as once observed here, then indigenous geographies are also unfinished. Similarly, Reidun and Aslak “are not finished with” their Arctic View venture or their explorations of potentially transformative practices which tie them to the past while making a future. Their story is also unfinished. “But we have to stop at some point and finish this writing,” Aslak concludes.

Closing comments

While relying on geographical, anthropological and sociological theoretical perspectives, the analysis demonstrates how indigeneity can be identified as contingently emerging meaning aspects in the entrepreneurship process. In other respects, the particular entrepreneurship story above is just as “unrepresentable” (cf. Clifford, Reference Clifford2013, p. 6) as it is unfinished. Our intention in keeping the story open is “…to leave scope for readers of different backgrounds to make different interpretations and draw diverse conclusions regarding the question of what the case is a case of.” (Flyvbjerg, Reference Flyvbjerg2006, p. 238). The uniqueness of the story of Reidun and Aslak’s entrepreneurship appears as we get to know it in-depth and learn about its many nuances and connections in time and space. Its value for knowledge development concerning indigenous tourism entrepreneurships lies in the richness of our analytical narrative and the different possibilities for researchers around Sápmi and the world to connect to it as a case of something that becomes relevant in their own research.

Still, we would like to emphasise two more general points concerning the development of Sámi tourism. First, the material, geographical and historical situatedness of Sámi tourism entrepreneurships implies that politicians and others who expect Sámi people to become agents in Arctic destinations should make their approaches with an awareness of the unfinished geographies of Sápmi. Tourism entrepreneurships rely on extrovert endeavours in place that unavoidably interferes with the historical and geographical continuities and transformations of places in Sápmi. To become part of processes where a place, for example, becomes “more Sámi” can energise an entrepreneurship. At the same time, it can add social and emotional, as well as economic, vulnerability. As Aslak puts it, an entrepreneurship like this is like an uncooked egg. Awareness of and respect for the risks that cling to indigenous entrepreneurships in tourism are not least important within communities along the coast of Norwegian Sápmi, which are often Sámi minority communities. Finally, and as we have seen in this story from the coast, Sámi entrepreneurs of today may start up their tourism ventures not only in new places but also in ways that frame Sámi qualities in tourism in new and unexpected ways. The indigenous becomings at Arctic View should be recognised and valued as outcomes of endurance and as indications of a more heterogeneous Sámi tourism landscape in-the-making that can encourage more Sámi people to engage in the tourism economy in the years to come. Financial support

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway, Regionalt forskningsfond, Fondsregion Nord-Norge (RFFNORD).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.