The 2021–2023 Russian chairmanship

Pursuant to the terms of the Reykjavik Declaration adopted on 20 May 2021 at the Ministerial Meeting marking the close of Iceland’s term as chair of the Arctic Council (AC), the Russian Federation has assumed the chairmanship of the council for the second time (Arctic Council, 2021). While Russia has been an active participant in the activities of the council over the years, prevailing conditions have shifted markedly in the period since Russia’s first term as chair during 2004–2006. The impacts of climate change in the high latitudes have increased dramatically; the pace of extraction of the Arctic’s natural resources has accelerated sharply; the volume of shipping in Arctic waters is growing, and great-power politics have become more prominent in the region raising concerns about issues of military security in the Arctic. As a recent US Government document forecasts, “Arctic waters will see increasing transits of cargo and natural resources to global markets along with military activity, regional maritime traffic, tourism, and legitimate/illegitimate global fishing fleets” (US Navy, 2020). Taken together, these developments have generated a pivotal moment for the AC together with a growing collection of related governance arrangements. Under the circumstances, a simple plan calling for business as usual will not suffice to ensure continued success in addressing needs for governance in the Arctic during the 2020s. The challenge today is to adapt the Arctic governance system to changing circumstances, without disrupting the ongoing work of the AC and related bodies in a variety of functional areas.

Following the provisions of the Reykjavik Declaration (Arctic Council, 2021) and the Arctic Council Strategic Plan 2021 to 2030 (Arctic Council, 2021a) adopted at the same time, Russia has developed a detailed programme for its 2021–2023 chairmanship (Arctic Council, 2021b). Under the umbrella theme of “Responsible Governance for a Sustainable Arctic”, the Russian Chairmanship Programme sets forth plans for a sizeable number of substantive initiatives during Russia’s 2021–2023 term as chair (Arctic Council, 2021b). These are positive steps reflecting a serious commitment to constructive leadership in the AC.

Nevertheless, we are still left with the question of how to adapt the council and related Arctic arrangements to the far-reaching changes in the conditions affecting Arctic governance in the 2020s. This is our primary concern in this article. Specifically, we ask what opportunities will Russia have during the course of its chairmanship to take the lead in initiating adjustments in existing arrangements needed to ensure success in responding to issues of governance arising in the Arctic in the coming years? We address this question in several steps. The next section provides background regarding the treatment of the AC in Russian law and policy, including some observations concerning the record of Russia’s first term as council chair during 2004–2006. The next section sets the stage for our analysis of options by summarising the key elements of the 2021 Reykjavik Declaration, the Arctic Council Strategic Plan 2021 to 2030, and the Russian Chairmanship Programme.

We preface our exploration of options in the following section with a consideration of two overarching challenges confronting Arctic governance today: (i) how to reconcile the promotion of economic development with a concern for environmental protection and sustainability in the face of growing impacts of climate change and (ii) how to deal with the increasing prominence of matters relating to great-power politics and military security in the discourse regarding Arctic issues. From this point of departure, we turn to an exploration of several specific areas where we believe there are opportunities to adapt the AC and related arrangements to conditions prevailing in the 2020s. In a brief concluding section, we offer a concrete proposal regarding an initiative during the Russian Chairmanship that could energise the efforts of the AC to meet the challenge of adaptation, without disrupting its ongoing work.

The AC in Russian law and policy

With a coastline bordering almost half of the Arctic Basin and a population comprising roughly half of the human residents of the Arctic region, Russia is in many respects the pre-eminent Arctic state. The Arctic – sometimes separated into the High Arctic and the North in Russian discourse – figures prominently in Russian history and is an important focus of attention in Russian policy today. This means that Russia’s policy regarding the role of the AC is embedded in an extensive body of experience with Arctic affairs.

Prior to the initiation of perestroika in the 1980s, the Arctic policy of the Soviet Union was clear-cut. There was no place for any international institutions engaging in activities that might affect the Soviet Union’s “Arctic sector” (Scovazzi, Reference Scovazzi, Elferink and Rothwell2001, pp. 81–83; Vylegzhanin, Reference Vylegzhanin and Berkman2019, p. xv–xxiii) as defined in the official decree of 1926 “On the Proclamation of Lands and Islands Located in the Arctic Ocean as Territory of the USSR” (Berkman et al., Reference Berkman, Vylegzhanin and Young2019, p. 216). During the cold war, the Soviet government would never have agreed to a document like the 1996 Ottawa Declaration on the Establishment of the Arctic Council, creating a forum the majority of whose members were also members of NATO (Arctic Council, 1996). This led some Russian policymakers to criticise President Gorbachev for encouraging the internationalisation of the country’s Arctic sector during the 1980s as well as for triggering developments leading to the collapse of the USSR (Arbatov, Reference Arbatov and Zagorsky2010, pp. 10–15).

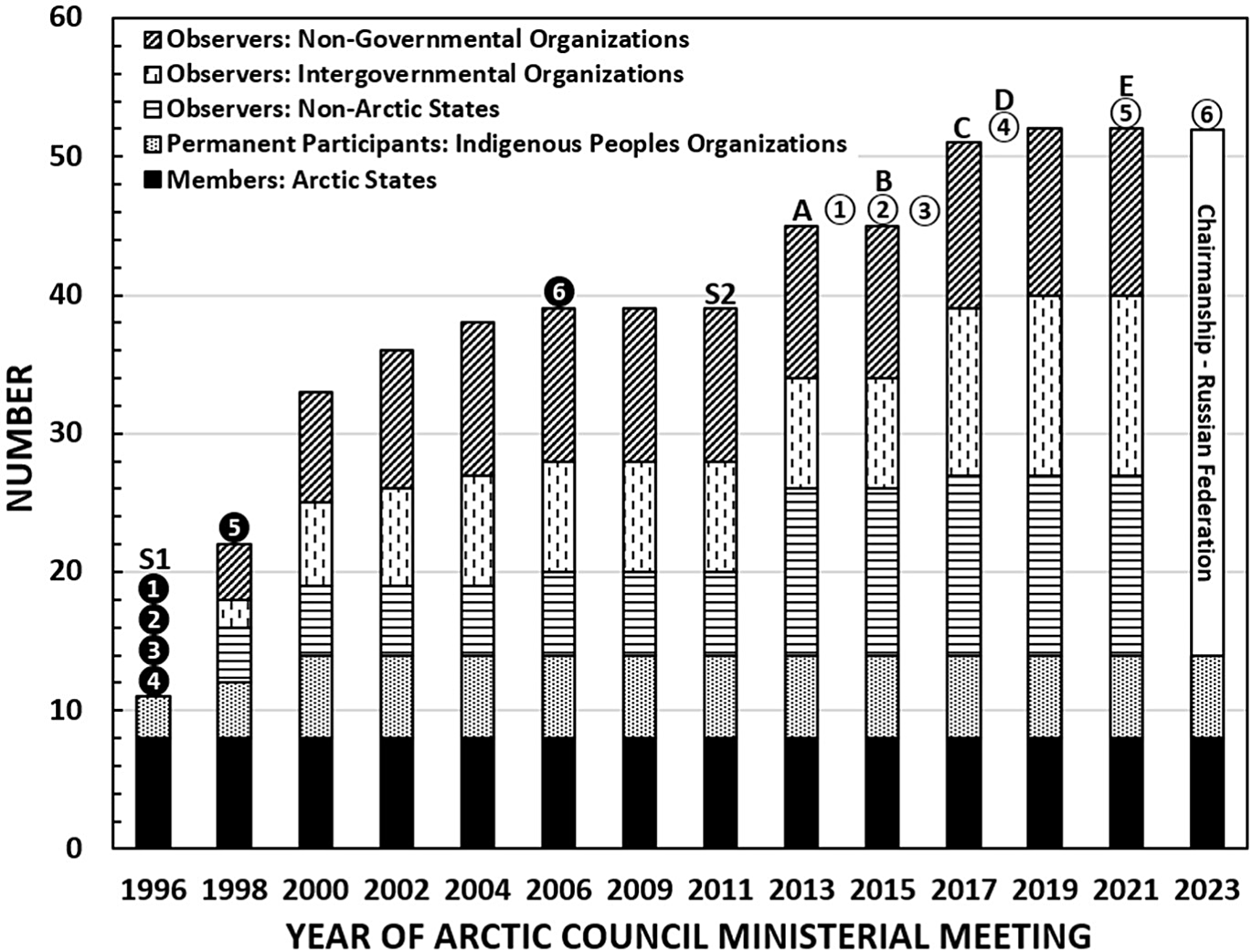

Yet many Russian observers have come to regard the creation of the AC as one of the most successful outcomes of cooperation among the Arctic states at the regional level (Korchunov & Tevatrosyan, Reference Korchunov and Tevotrasyan2020, p. 9; RIAC, 2021, pp. 5–6; Vylegzhanin, Reference Vylegzhanin and Berkman2019, pp. xviii–xix). They agree that the accomplishments of the AC have exceeded the expectations of those who took part in the creation of the council during the 1990s. They support the evolution of the organisational structure of the council over time as portrayed in Figure 1, and they share the view of those who nominated the council in 2018 for the Nobel Peace Prize as a model for maintaining regional peace and stability rather than falling prey to the geopolitical tensions prevailing outside the Arctic (Dudikina, Reference Dudikina2016, p. 251–297). As the participants in the May 2013 Ministerial Meeting in Kiruna marking the close of the Swedish chairmanship put it, “the Arctic Council has become the pre-eminent high-level forum of the Arctic region and we have made this region into an area of unique international cooperation” (Arctic Council, 2013b).

Figure 1. History of the Arctic Council system during the 25 years since the adoption of the 1996 Ottawa Declaration, showing the number of Members (Arctic states), Permanent Participants (Indigenous Peoples Organizations), and Observers (non-Arctic states, intergovernmental organisations and non-governmental organizations) associated with the Arctic Council Ministerial Meetings (ACMM) based on details from the Arctic Council website (https://arctic-council.org/en/). Note all ACMMs were two years apart except for 2006 and 2009. Also shown are years the six Arctic Council Working Groups (circles with black backgrounds) began contributing to the Arctic Council: Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response (EPPR), and Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME) in 1996 along with the Sustainable Development Working Group (SDWG) in 1998 and the Arctic Contaminants Action Program (ACAP) in 2006. Also shown are years when secretariats became associated with the Arctic Council: Arctic Indigenous Peoples Secretariat (S1) and Arctic Council Secretariat (S2). Affiliated initiatives that now align with rotation of the Arctic Council chairmanship are shown (circles with white backgrounds): Arctic Economic Council (2014); Arctic Coast Guard Forum (2015); 1st Arctic Science Ministerial (2016); 2nd Arctic Science Ministerial (2018); 3rd Arctic Science Ministerial (2021); and 4th Arctic Science Ministerial (2023). Also shown are the year of “Entry into Force” of binding Arctic agreements that have emerged since the Arctic Council was established in 1996: 2011 Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic in 2013 (A); 2013 Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic in 2016 (B); International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Water (Polar Code) adopted through the International Maritime Organization in 2017 (C); 2017 Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation in 2018 (D), and 2018 Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean in 2021 (E).

The ability of the Arctic states to create a successful regional mechanism is rooted in history, since these states have acted to shape the legal status of the region beginning with the Arctic convention of 1825 in which Great Britain and Russia established a boundary between their colonial domains in what is now Canada and Alaska. This bilateral action did not provoke protests from other states, despite legally challenging words in the convention regarding the “polar possessions” of Great Britain and Russia in the Arctic Ocean and “the meridian” (sector) boundary delimiting their possessions in the Arctic. At the time, non-Arctic states had no practical interest regarding the jurisdictional status of Arctic spaces (Berkman et al., Reference Berkman, Vylegzhanin and Young2019). Emerging at the close of the 20th century, the AC descends from this much earlier treatment of the Arctic as a distinctive international region with a unique legal status.

Though some Russian analysts criticised Gorbachev for allowing NATO to strengthen its presence in the Arctic, most have come to regard the development of the AC as a confirmation of the legal and political identity of the Arctic region (Ivanov, Reference Ivanov2018, p. 5; Vasilyev, Reference Vasilyev2021, p. 1; Vylegzhanin, Reference Vylegzhanin and Berkman2019, p. xix). There were no differences regarding the role of the council when the Arctic was a peripheral region in world affairs. But today, circumstances have changed. The Arctic “may become our first frontier” rather than the last frontier (Spohr and Hamilton, Reference Spohr and Hamilton2020, p. 1). Many international organisations now interact with the council, some in the role of AC Observers. Some of these interactions became feasible only after the close of the cold war. A prominent example is the role of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in establishing the Polar Code regulating Arctic shipping, partly in response to the Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment conducted by the AC and the continuing engagement of the council’s Working Group on the Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (Arctic Council, 2009).

For Russia, economic development in the Russian North and the stability of its Arctic communities were the top priorities in the 1990s. They remain so today, and they figure prominently in Russia’s Arctic policy documents (Russian Government, Reference Russian2020; Russian Government, Reference Russian2020a). Under the circumstances, Russia’s Arctic agenda differs somewhat from the priority others attach to environmental protection (Oldberg, Reference Oldberg2011, pp. 42–43). Though Russian policymakers attach importance to the goal of strengthening the sustainability of Arctic communities, they are committed to a vision of the Arctic as a central component of the country’s economy. Nevertheless, Russia acceded during its 2004–2006 chairmanship to “the majority view on prioritizing ecology and nature protection, rather than insisting on according priority to social and economic aspects of Arctic governance” (Oldberg, Reference Oldberg2011, p. 39).

In this spirit of compromise, Russia supports the AC as a regional body with a mandate to serve as a high-level forum for the consideration of Arctic issues and with a membership limited to the eight Arctic states. The importance of this regional approach to Arctic affairs is spelled out in the 1996 Ottawa Declaration and has been reiterated by the responsible political leaders and ministers of the eight Arctic states acting within the framework of the AC. Only the Arctic states that have citizens living in the Arctic and that exercise sovereignty and jurisdiction over the vast areas of the region share responsibility for the future of the Arctic’s inhabitants, including Indigenous peoples. The ministers of the Arctic states in consultation with representatives of the Permanent Participants make important decisions by consensus. Working groups and other subsidiary bodies prepare these decisions carefully, and the Senior Arctic Officials representing the foreign ministries of the member states review them in preparation for action on the part of the ministers. Non-Arctic states seeking to participate in the activities of the council as Observers recognise this reality in accepting the Terms of Reference for Observers adopted by the members of the AC. Thus, Observers must “accept and support the objectives of the Arctic Council defined in the Ottawa Declaration”, and they are expected to recognise “Arctic States’ sovereignty, sovereign rights and jurisdiction in the Arctic” (Arctic Council, 2013a).

Today, Russia takes for granted the central role of the AC in environmental and economic governance of the Arctic, though some Russian sources criticise specific activities of the council (Panichkin, Reference Panichkin2013, p. 154). The acceptance of non-Arctic states, including major Asian states like China as well as leading European members of NATO (e.g. France, Germany, Great Britain), as AC Observers confirms Russia’s pragmatic approach to the activities of the council (Korchunov & Chilingarov, Reference Korchunov and Chiilingarov2019, p. 6–7). Beginning with Great Britain and Germany in 1998, more and more states have applied for the status of AC Observer and have been accepted by the council (see Figure 1). Additional states have applied for Observer status, though no applications were approved at the 2021 AC Ministerial Meeting, and the likelihood that their applications will be accepted during the foreseeable future remains unclear.

Most Russian commentators share the view that what makes the AC successful as a mechanism for devising balanced approaches to Arctic issues is the fact that the members make decisions by consensus (Arctic Council, 1996). Though consensus is sometimes difficult to achieve, decisions arrived at through this process are particularly influential. When the members of the AC are able to move forward by consensus, it is hard for other states to oppose the results, despite the legal principle of pacta tertiis nec nocent nec prosunt (an international agreement does not bind third parties without their consent) formalised in the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. Operating in this spirit, Russia served as co-lead of the Arctic Council Task Forces that developed the provisions of the 2011 agreement of search and rescue, the 2013 agreement on marine oil spill preparedness and response, and the 2017 agreement on enhancement of cooperation in Arctic science.

As articulated by the president who has authority under the constitution to represent the Russian Federation, Russia takes the view that there is also a legitimate role for the Arctic 5, including Canada, Denmark/Greenland, Norway, Russia, and the United States as Arctic Ocean coastal states, in contrast to the Arctic 8, including all members of the AC. Only the Arctic 5 are signatories to the 1973 Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears; only the Arctic coastal states are signatories to the 2008 Ilulissat Declaration. These measures deal with issues of particular interest to states that (i) have sovereignty over internal waters and over the territorial sea in the Arctic up to the limit not exceeding 12 nautical miles measured from baselines in the direction of the sea, (ii) have sovereign rights in regard to natural resources within their 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zones established by respective domestic legislative acts, and (iii) have sovereign rights over their own portion of the continental shelf in the Arctic, including the subsoil, for the purpose of exploring and exploiting natural resources. Some observers have argued that action by the Arctic 5 in adopting measures like the Ilulissat Declaration “threatens to weaken” the AC (Oldberg, Reference Oldberg2011, p. 36). But, in reality, others have accepted the special interest of the Arctic 5 in marine issues, and these dire predictions have not been borne out in practice (Byers, Reference Byers2013).

A distinct question concerns the role of non-Arctic states in matters that involve them directly or touch on their rights under the provisions of the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS, 1982). For example, the 2011 search and rescue agreement contains a provision allowing non-Arctic states to “contribute to the conduct of search and rescue operations, consistent with existing international agreements” (Article 18). The Arctic states accepted non-Arctic states as signatories to the 2018 Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement due to the fact that the agreement covers areas of the high seas in which all states that are signatories to the law of the sea convention have rights. Still, it is worth noting that access to the high seas of the Central Arctic Ocean requires passage through areas (e.g. the Bering Strait) under the jurisdiction of the Arctic states and would in practice necessitate reliance on coastal infrastructure and communications facilities. Russia acknowledges the legitimacy of these interests on the part of non-Arctic states as exemplified in its active participation in the development of the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement (Vylegzhanin et al., Reference Vylegzhanin, Young and Berkman2020). At the same time, there is a range of perspectives both in Russia and elsewhere regarding the merits of including non-Arctic states like China in cooperative arrangements dealing with Arctic issues (Lackenbauer & Manicom, Reference Lackenbauer, Manikom, Hara and Coates2013; Conley et al., Reference Conley2017).

Russia’s position regarding the role the intergovernmental organisations that have been accepted as AC Observers (see Figure 1) is generally cautious. Russia shares the common view that interaction between the council and these observer organisations can play a constructive role in harmonising the increasingly complex network of Arctic governance mechanisms. Including a body like the IMO, for example, as an AC Observer is helpful in integrating the work of the AC’s Working Group on the Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment on Arctic shipping and the rule-making activities of the IMO recognised under UNCLOS as the “competent international organization” in the field of “navigation, including pollution from vessels”. More generally, Observers can play a role in contributing to informed decision-making regarding issues of common concern. On the other hand, there is a concern that growth in the ranks of intergovernmental organisations as AC Observers may accentuate the interests of international bureaucracies in contrast to the interests of the member states in the deliberations of the council (Ivanov, Reference Ivanov2013, p.16).

During its 2004–2006 chairmanship, as noted, Russia opted to steer a course conforming to the Ottawa Declaration’s emphasis on environmental protection and sustainable development. A particular concern at that time was the importance of addressing problems of environmental contamination resulting from poorly regulated industrial activities and hasty decommissioning of ships and military installations in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Russian initiatives in this realm led to an emphasis in the work of the AC on projects aimed at addressing contamination, eventuating in the establishment of the Arctic Contaminants Action Program as a sixth working group of the council in 2006. More generally, this experience reflects a concern with environmental problems associated with industrial activities in the Arctic. As exemplified by the NorNickel oil spill of 2020, such problems remain prominent in the Arctic today, and it is reasonable to accept at face value Russia’s declared intention to take an active interest in avoiding their occurrence and responding vigorously to such incidents when they do occur. Nevertheless, the growing impacts of climate change are likely to heighten the salience of such problems during the coming years (Greenpeace, 2011).

Another theme prominent in the 2004–2006 chairmanship featured issues involving relationships among the various elements of the AC. The Salekhard Declaration, adopted at the close of the first Russian Chairmanship in 2006, requests the Senior Arctic Officials to take up questions regarding the efficiency and effectiveness of the council’s structure going forward (Arctic Council, 2006). In reality, this issue has become more complex in recent years with the creation of Task Forces, Expert Groups, and a Permanent Secretariat along with the establishment of formally independent but closely aligned bodies like the Arctic Coast Guard Forum and the Arctic Economic Council. Russia has a continuing interest in rationalising the structure of the AC, an issue to which we return in the discussion of opportunities arising during the 2021–2023 chairmanship in a later section.

The state of play following the 2021 Ministerial Meeting

Following the established practice of the AC, the provisions of the Ministerial Declaration adopted at the end of one chairmanship serve also to set the course for the activities of the incoming chair. Thus, we can turn first to the provisions of the 2021 Reykjavik Declaration, developed through consultation between Iceland as the outgoing chair and Russia as the incoming chair and signed by the foreign ministers of the eight Arctic states, to get a sense of what is envisioned for the 2021–2023 biennium (Arctic Council, 2021). In Reykjavik, members of the AC also broke new ground by adopting the Arctic Council Strategic Plan 2021 to 2030 (Arctic Council, 2021a). It is helpful to consider both documents together in asking about the council’s own views regarding forthcoming activities.

The declaration starts out by celebrating the “25th anniversary of the Arctic Council and the progress achieved towards its commitment to sustainable development in the Arctic region and to the protection of the Arctic environment”. It then proceeds to hail the council as the “preeminent forum for cooperation in the region”. What follows is a set of 62 specific provisions noting, recognising, and welcoming a wide range of developments, including in the first instance achievements occurring during the Icelandic chairmanship in the areas of people and communities of the Arctic; sustainable economic development; climate, green energy solutions, environment, and biodiversity, and Arctic marine environment. The declaration identifies some specific accomplishments, such as the development of the Circumpolar Biodiversity Monitoring Program Strategic Plan (2021–2025), the completion of the Regional Action Plan on Marine Litter in the Arctic, and the launching of the SAO-based Marine Mechanism. The general tone of the declaration is that the council is performing well and should continue to pursue specific initiatives falling within its existing remit. The declaration does acknowledge the “need to ensure that the Council is ready to meet future challenges”, and it endorses several measures relevant to achieving this goal.

The adoption of an Arctic Council Strategic Plan is a significant innovation for the council. First proposed during the 2015–2017 US Chairmanship, the idea of adopting a strategic plan became a focus of extensive discussions over a period of years. The document adopted in Reykjavik begins with an assertion that “[i]n 2030 we envision the Arctic to remain a region of peace, stability and constructive cooperation, that is a vibrant, prosperous, sustainable and secure home for all its inhabitants, including Indigenous Peoples, and where their rights and wellbeing are respected” (Arctic Council, 2021a: 1). In furtherance of this vision, the plan calls on the council to play active roles in seven areas, including Arctic climate; healthy and resilient Arctic ecosystems; healthy Arctic marine environment; sustainable social development; sustainable economic development; knowledge and communications, and a stronger AC. As is often the case with strategic plans, this one encompasses a wide range of themes; it does not set explicit priorities or describe specific activities that are to be initiated and completed within a specified period of time in the interests of meeting these priorities. Nevertheless, the plan does contain a list of 49 things that the council “will” do to fulfill its goals in the seven thematic areas. In this sense, it provides a useful guide to thinking in the policy communities of the Arctic states regarding matters than can and should be addressed in the coming years.

To gain a concrete picture of what is in store during the 2021–2023 biennium, it is necessary to turn to several documents Russia has prepared, including a detailed pamphlet entitled Russia’s Chairmanship Programme for the Arctic Council 2021–2023 submitted to the May 2021 Ministerial Meeting (Arctic Council, 2021b). Adopting the overarching vision of “Responsible Governance for a Sustainable Arctic”, the Russian Federation proposes to pursue this vision through “promoting collective approaches to the sustainable development of the Arctic, environmentally, socially and economically balanced, enhancing synergy and coordination with other regional structures, as well as implementation of the Council’s Strategic Plan, while respecting the rule of law” (Arctic Council, 2021c, p. 1). Within this rather grand vision, Russia has identified a set of thematic priorities for its chairmanship. Individual documents phrase these priorities somewhat differently, but the centre of gravity in the various formulations features people of the Arctic, including Indigenous peoples; environmental protection, including climate change; socio-economic development, and strengthening of the AC.

Stated in general terms, these priorities are by no means novel; they all cover issue domains that have occupied the attention of the council from its inception. But what is notable about the Russia’s Chairmanship Programme for the AC is that it identifies a large number of concrete activities that Russia proposes to organise under the umbrella of this programme. Overall, “[m]ore than 100 international Arctic events, divided into 11 thematic clusters, are planned within the framework, and under the auspices, of the Russian Chairmanship in a hybrid face-to-face and online format” (Arctic Council, 2021b, p. 5). These events range from an annual Northern Sustainable Development Forum through convening the Third Biodiversity Congress, conducting exercises to prevent emergencies, holding a conference on green energy, transport infrastructure, and sustainable navigation and on to completing the year round “Snowflake” International Arctic Station powered by hydrogen.

In the nature of things, the transition from paper to practice is almost always complex and often generates issues that are tricky to resolve. Some of the initiatives identified in the programme will likely fall by the wayside for one reason or another. Others will evolve into events that differ more or less significantly from what is envisioned in the chairmanship programme. Nevertheless, this is an impressive plan that reflects serious interest on the part of Russia in the work of the AC, considerable thought on the part of Russian officials interested in Arctic affairs, and a willingness to invest resources in activities to be carried out under the auspices of the council. The first (hybrid) AC executive meeting under the Russian Chairmanship, which took place in Moscow on 29–30 June 2021, focused on work plans to follow up on action items included in the Reykjavik Declaration, priorities identified in the Arctic Council Strategic Plan, and initiatives and side events called for under the Russian Chairmanship Programme (Arctic Council, 2021d).

Responding to the challenges of the 2020s

There can be no doubt, then, that Russia has adopted a pro-active approach to its 2021–2023 chairmanship of the AC. Still, there is a clear sense in which both the Arctic Council Strategic Plan and the Russian Chairmanship Programme envision the existence of an overarching biophysical, socio-economic, and geopolitical setting that is not materially different from the setting prevailing in earlier years. This is where larger concerns about the future of Arctic governance come into focus. We turn now to an exploration of specific ways to adapt the AC and related bodies to major changes in conditions prevailing in the Arctic both to ensure continued success in the realm of Arctic governance and to examine opportunities for the 2021–2023 Russian Chairmanship to play a constructive role in dealing with the future of Arctic governance.

Two overarching issues provide the context for this exploration: one centres on the tension between mainstream economic development and environmental protection/sustainability in the Arctic; the other arises from the growing concern about increasing military activities in the Arctic and the tendency to adopt what international relations scholars call a narrative of securitisation in analyses of Arctic affairs. How these overarching issues play out in the coming years will have a determinative effect on the treatment of issues arising in the AC and related bodies.

Arctic economic development has emerged as a cornerstone of Russia’s strategy for rebuilding its economy and reasserting its claim to great power status. Well-informed Russian analysts have stated that Arctic activities account for ∼15% of the Russian Federation’s current GDP and a similarly large fraction of the Russian government’s revenue flow (Mitrova, Reference Mitrova and Corell2019, p. 205). This has given rise to a concerted effort at the highest levels to coordinate public policies and corporate initiatives together with the integration of external funding to promote the production and shipment of natural resources from the Arctic to southern markets at home and abroad. The rapid and continuing development of northwestern Siberia’s massive deposits of natural gas and the deployment of sophisticated LNG tankers to transport this gas along the Northern Sea Route to European and Asian markets exemplify this pattern. At the same time, the disruptive impacts of climate change are posing mounting problems in such forms as melting permafrost, flooding, wildfires, and extreme heat waves, raising urgent questions about adaptation strategies for human settlements throughout the Arctic as well as the protection of Arctic ecosystems (NOAA, 2020). There is no simple way to resolve the resultant tensions. But they constitute an increasingly prominent feature of the landscape of Russia’s Arctic policy. Balancing the drive to promote economic development and the need to secure the resilience of communities constitutes one key fulcrum of Russia’s Arctic policy.

Recent years have produced a pronounced increase in the attention devoted to great-power politics and, more specifically, military security in the international discourse regarding Arctic issues. As Russian policymakers have emphasised repeatedly, activities like the rebuilding of the Northern Fleet and the reoccupation of abandoned cold war military installations in the Arctic are not indications of a belief on the part of Russian policymakers that the Arctic is transitioning from a zone of peace to a zone of conflict. But there is no denying the growing prominence of great-power politics in the Arctic and the propensity of analysts in both Arctic states and non-Arctic states to frame Arctic issues in the language of geopolitics. An emphasis on rising tensions among China, the United States, and Russia is a central feature of this way of framing Arctic issues (Pincus, Reference Pincus2020). The United States, in particular, has taken a number of concrete steps (e.g. the deployment of the reactivated 2nd Fleet and the publication of a number of policy documents) motivated by a concern regarding the remilitarisation of the Arctic. This development raises complex questions about the role of the AC whose founding document includes an explicit injunction to avoid dealing with matters of military security in its constitutive provisions (Arctic Council, 1996).

These concerns provide a backdrop for an exploration of ways to adapt the Arctic governance system to conditions prevailing in the 2020s. In the following subsections, we consider a range of options dealing with (i) adjustments in the AC’s constitutive arrangements, (ii) interactions between the council and related governance arrangements, (iii) the role of science diplomacy, and (iv) issues of military security. The central issue throughout concerns opportunities Russia may want to explore during its 2021–2023 AC chairmanship.

Considering constitutive adjustments

A key question for Russia in consideration of the Reykjavik Declaration’s emphasis on a “stronger Arctic Council” is whether to propose inclusion in the terms of the 2023 ministerial declaration of pragmatic adjustments in the council’s constitutive arrangements. The issue here involves an assessment of whether there is a need to reconfigure the council to allow it to play an effective role as a “high-level forum” dealing with matters of Arctic governance arising under conditions prevailing in the 2020s.

The 1996 Ottawa Declaration on the Establishment of the AC is a legal document. But it is not an international treaty as defined by the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. As signatories, the eight Arctic states have not created the AC as an intergovernmental organisation based on an international treaty; they have not agreed explicitly to abide by its decisions, and they have not granted the AC the authority to make legally binding decisions. That is why the 2011, 2013, and 2017 agreements are not formally AC agreements, though they were signed in conjunction with AC Ministerial Meetings. In 1996, the members states emphasised the positive in contrast to the negative features of this arrangement, highlighting its flexibility in accommodating the interests of different states in the Arctic (Exner-Pirot et al., Reference Exner-Pirot, Ackren, Loukacheva, Nicol, Nilsson and Spense2019). But there is no denying that this situation imposes significant limitations on the work of the council.

Is it an option for Russia to advocate the establishment of a formal legal basis for the AC or at least to put this question on the AC Agenda for the next chairmanship? While the USSR traditionally preferred treaty obligations, clearly formulated and formalised in legally binding instruments rather than soft-law declarations or references to international customs, this is not a uniform preference in contemporary Russian legal policy (Dudikina, Reference Dudikina2016, pp. 21–35).

On the one hand, starting from 1996, the eight Arctic states, including Russia, have adhered to the provisions of the 1996 Declaration as if this document were a treaty or an international legally binding instrument. This may be regarded as evidence that the members of the council have come to regard the provisions of the Ottawa Declaration as customary international law, taking into account the tacit acceptance of this practice by other states. On the other hand, within the current constitutive arrangements, the government of any Arctic state may at any moment block the activities of the council, even if its parliament (or other legislative authority) does not support such a move on the part of the Government. That is an advantage for some governments and a disadvantage for others. To alleviate this legal fragility, the Arctic states might consider formalising the constitutive features of the AC in a legally binding agreement. Another option would be to develop a protocol to the 1996 Ottawa Declaration, making contemporary adjustments in the governance system embedded in the 1996 Declaration to meet the challenges in the 21st century, without changing its soft-law format.

A protocol to the Ottawa Declaration might mandate paying more attention, for example, to the exchange of information about environmentally friendly infrastructure and technologies in the Far North to meet the needs of local inhabitants of the Arctic, including Indigenous peoples, and to promote adaptation to the impacts of climate change. In this regard, the council might devote more attention to practical concerns like encouraging the introduction of technologies to provide indoor plumbing in the houses of Arctic communities in contrast to the production of bulky studies of various aspects of sustainable development.

This does not mean that general concerns regarding environmental security (Berkman and Vylegzhanin, Reference Berkman and Vylegzhanin2013) should be dropped from the AC’s agenda. Success stories like the 2004 Arctic Climate Impact Assessment and the 2009 Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment should be treated as models for future initiatives (ACIA 2005; Arctic Council 2009). The same is true regarding other successful initiatives like the work of the Expert Groups on ecosystem-based management and on black carbon and methane and the development of the 2015–2025 strategic plan for protecting marine and coastal Arctic ecosystems. But there is a need to reconfigure the council to increase the priority accorded to issues relating to the urgent needs of the peoples of the North in the rapidly changing Arctic environment.

Organising relations with other international bodies

The 2013 Ministerial Declaration noted “the leadership of the Arctic Council in taking concrete action to respond to new challenges and opportunities” (Arctic Council, 2013). Nevertheless, the council does not have any political or legal monopoly regarding the handling of needs for regional governance. The Nordic Council of Ministers, for example, was created in 1971 without the participation of Russia; the Barents Euro-Arctic Council was created in 1993 without the participation of Canada and the United States. In general, these bodies coexist peacefully and productively, highlighting the prospects for fruitful cooperation between the AC and other international bodies.

In this context, the Russian chairmanship may consider ways to strengthen cooperation between the AC and several other members of the growing constellation of international bodies concerned with Arctic issues and interacting with the council. One prominent case involves interaction with the Arctic Coast Guard Forum. The forum is an intergovernmental organisation established in October 2015 under the terms of the Joint Statement of Intent to Further Develop Multilateral Cooperation of Agencies Representing Coast Guard Functions (Arctic Coast Guard Forum, 2015). Representatives of all eight Arctic states signed this document. The signatories adopted Terms of Reference for the organisation according to which the Arctic Coast Guard Forum is an “independent, informal operationally driven organization, not bound by treaty, to foster safe, secure, and environmentally responsible maritime activity in the Arctic”. The forum is already collaborating with the AC’s Working Group on Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response regarding implementation of the 2013 Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic. Such collaboration includes, for example, joint exercises for oil pollution response. A logical next step would be to grant the Arctic Coast Guard Forum formal Observer status in the AC.

Turning to the Arctic Economic Council, we note that in April 2019 the heads of the Secretariats of the two organisations (but not representatives of the members of the AC) signed a Memorandum of understanding between the AC and the Arctic Economic Council (Arctic Economic Council, 2020). This document provides for an organisational connection between the AC and the Arctic Economic Council, which is described as “an independent organization” with a mandate to contribute to the “responsible economic development” of the Arctic Region, first of all by facilitating exchanges of “best practices” and technologies. Some observers have noted that “[e]fforts to promote economic development have been mostly relegated to the Arctic Economic Council” but that the AEC “has limited capacity” and its relationship with the AC “remains ambiguous” (Exner-Pirot et al., Reference Exner-Pirot, Ackren, Loukacheva, Nicol, Nilsson and Spense2019). Others have adopted a different view of the relationship, emphasising that the AEC is a meeting place for private actors not formally subordinate to governments but informally guided by the actions of the council relating to environmental protection and sustainable development (Korchunov & Tevotrasyan, Reference Korchunov and Tevotrasyan2020, p. 6). This suggests that the Russian Chairmanship might want to undertake an evaluation of the AC–AEC relationship with an eye towards encouraging fruitful cooperation.

Another case involves clarifying the relationship between the AC and bodies dealing with scientific matters, including the International Arctic Science Committee (IASC) and the Arctic Science Ministerial (ASM) Meetings. Established in 1990 by the eight Arctic states, IASC is formally a nongovernmental organisation. But its members are national scientific organisations (e.g. national academies of sciences). IASC now has 23 members and has Observer status with the AC (IASC, 2021). IASC collaborates actively with AC working groups including the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program, the Working Group on the Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment, and the Working Group on the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna. IASC collaborated with the AC in producing the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment and is currently involved in a number of AC projects, including Actions for Arctic Biodiversity 2013–2021; the Sustaining Arctic Observing Network, and the project on Blue Bioeconomy in the Arctic Region. The de facto collaboration between the AC and IASC is strong. But it has no explicit basis in the Ottawa Declaration or in the AC’s Rules of Procedure.

The ASM Meetings originated with what was envisioned initially as a single gathering organised during the US chairmanship of the AC in 2016. Subsequent meetings have led to the emergence of an informal but recognised practice. The third ASM meeting organised by Iceland and Japan and hosted by Japan took place in May 2021 at the close of the Icelandic chairmanship. Russia has indicated that it intends to organise/host (probably in collaboration with France) a fourth ASM during the course of its 2021–2023 chairmanship. Participation in the ASMs is not limited to members of the AC. Nevertheless, it would be appropriate now to provide more formal recognition of this practice and to clarify its role in the growing family of international bodies dealing with issues of Arctic governance.

Additional issues of a somewhat similar nature are coming into focus. Early in the Icelandic Chairmanship, for example, the Arctic states created a Senior Arctic Officials-based Marine Mechanism (SMM) to coordinate initiatives involving the Arctic Ocean. While the SMM is clearly a member of the AC family, its place in the constellation remains ambiguous. It is not a Working Group, a Task Force, or an Expert Group. But its remit cuts across the concerns of other AC bodies as well as organisations external to the council, such as the IMO. There is a need to clarify the role of the SMM to minimise contradictions and encourage synergy. With particular regard to conservation and rational management of marine living resources (including stock assessments), there is considerable interest in the establishment of an Arctic counterpart to the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) in the North Atlantic and the North Pacific Marine Science Organization (PICES) in the North Pacific to provide science-based input into policymaking regarding Arctic Ocean issues. Such a body would also complement work under the auspices of the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement, which entered into force on 25 June 2021. However, this proposal, too, raises questions regarding the place of a prospective new element in the constellation of bodies responding to need for governance relating to Arctic issues. Should such a body be based on an explicit intergovernmental agreement, for example, as is the case with ICES and PICES?

The point of this discussion is that there is a growing need to rationalise the structure of governance mechanisms dealing with Arctic matters not only to minimise the dangers of mutual interference but also to maximise the prospects for generating synergy in the realm of Arctic governance. There is no simple formula for rationalising this constellation of non-hierarchically related elements which analysts of governance think of as a regime complex (Oberthür and Stokke, 2011). But Russia is in a position to take the initiative in this realm during its 2021–2023 chairmanship by virtue of the facts that it will serve concurrently as chair of the AC Sustainable Development Working Group, the Arctic Coast Guard Forum and the Arctic Economic Council and as co-host of the ASM Meeting. An important point of departure in this realm is that most of the relevant players are now among the 38 non-Arctic states, intergovernmental organisations, and nongovernmental organisations that have the status of AC Observers. This gives the AC considerable convening power when it comes to addressing matters calling for formal cooperation or more informal collaboration among elements of the Arctic regime complex. Representatives of most of the distinct elements attend meetings of the AC’s Senior Arctic Officials, where they have opportunities to engage in informal interactions of the sort needed to work out the details of cooperative initiatives.

AC Observers are authorised to participate in council meetings and even to suggest their own drafts of documents for consideration (§38 of the Rules of Procedure of the AC). But both the status of Observers and the exact nature of their participation in council meetings remain a source of confusion. What is needed is a careful effort to rethink the role of AC Observers with the goal of improving the capacity of the Arctic regime complex to address challenging needs for governance under the conditions prevailing in the 2020s. Because the AC operates largely by consensus and achieves results by finding ways to knit together the concerns of many stakeholders and to provide leadership in launching widely supported initiatives, there may be opportunities to revisit the rules regarding the roles of various players in this increasingly complex constellation. No one wants to dilute the status of the eight Arctic states as members or the status of the six Indigenous Peoples Organizations as Permanent Participants. But there may be room to adjust the status of Observers to strengthen their role in addressing issues relating to harmonising the elements of the Arctic regime complex going forward. Given its concurrent chairmanships of a number of key elements during 2021–2023, Russia is in a strong position to exercise leadership in this increasingly important domain.

Foregrounding science diplomacy

Another issue for consideration during Russia’s chairmanship concerns the role of science diplomacy in contributing to informed decision-making regarding Arctic issues (Berkman et al., Reference Berkman, Vylegzhanin and Young2019, p. vii; Young et al., Reference Young, Spohr and Hamilton2020, pp. v–xxv). Hundreds of publications address the role of science in international law and policy, even suggesting a new branch of law sometimes described as the “global administrative law of science” (Reffert & Steinecke, Reference Ruffert and Steinecke2011, pp. 4–5). Here, we draw attention not only to the Arctic science agreement, negotiated by an Arctic Council Task Force co-led by the Russian Federation and the United States and signed at the 2017 AC Ministerial Meeting marking the close of the US Chairmanship, but also to broader contributions associated with the evolving practice of science diplomacy.

The legally binding 2017 agreement aims to enhance research cooperation in the Arctic by removing obstacles to collaboration and by providing mechanisms to facilitate access to research field sites on a pan-Arctic scale (Berkman et al. Reference Berkman, Kullerud, Pope, Vylegzhanin and Young2017). But much remains to be done in moving the provisions of the agreement from paper to practice and in integrating the provisions of this agreement with the related practices of the IASC and the initiatives of the ASM Meetings. Russia has assumed responsibility for the administration of the 2017 agreement during its AC chairmanship and has communicated clear interest in harmonising the various elements of the Arctic science system. As an initial step, Russia has announced its intention to organise a meeting in September 2021 to make a start in addressing this challenge.

More broadly, there is an emerging role for science diplomacy in promoting collaboration in addressing issues of Arctic governance by contributing to the formulation of questions, the gathering of data, the distillation of evidence, and the framing of options that together constitute the basis of what has become known as the co-production of knowledge for the pursuit of informed decision-making (Berkman et al., Reference Berkmanforthcoming). The value of these contributions is discussed not only among the foreign ministries of the Arctic states but also as a pivotal topic at the ASM Meetings (Berkman et al., Reference Berkman2017; Berkman, Reference Berkman, Scott and Vander Zwaag2020). But there is a need to take additional steps to refine the practice of science diplomacy and to apply it to the case of the Arctic. There is an opportunity for the Russian Chairmanship to play an active role in the progressive development of science diplomacy as applied to the Arctic. An encouraging step in this regard is the establishment in June 2021 of a Science Diplomacy Center at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO University), a leading player in Russia in education and research relating to matters of sustainability at the international level.

Attending to issues of military security

On 15 October 2020, “The Independent Barents Observer” published an article entitled “Moscow signals it will make national security a priority as Russia prepares to chair the Arctic Council” (Independent Barents Observer, 2020). The article notes that Dmitry Medvedev, a former president and prime-minister of Russia, “made clear” that “issues of national security will be part of his country’s upcoming chairmanship priorities in the Arctic Council”. But as the article notes, the 1996 Ottawa Declaration says specifically that “the Arctic Council should not deal with matters related to military security” (Arctic Council, 1996). How should we think about this issue? Is it timely to consider adjusting the provisions of the Ottawa Declaration or taking other steps, and is there an opportunity for Russian leadership in this realm?

It is easier to change the terms of an informal instrument like the Ottawa Declaration than the provisions of an international legally binding instrument. However, such changes are more difficult than reaching agreement on the agenda of the AC. While only six members are needed under the council’s Rules of Procedure to form a quorum for purposes of making decisions on the agenda (Arctic Council, 2013a), all eight members of the council would need to agree to any adjustments in the provisions of the Ottawa Declaration such as removing the prohibition on considering matters of military security. This means that even if it were possible to reach agreement regarding this issue, the first opportunity to make such a change would be at the time of the 2023 AC Ministerial Meeting. Thus, the adjustment would apply in practice to activities taking place after the close of the Russian Chairmanship.

Nevertheless, issues relating to military security are becoming increasingly prominent in the Arctic. They will not go away, even if we choose to ignore them in the activities of the AC. Issues pertaining to military security are often considered in more informal forums like Arctic Frontiers in Norway, the Arctic Circle in Iceland, and the Arctic as a Territory of Dialogue in Russia. The importance of these issues is also reflected in the Arctic policies of both Arctic and non-Arctic states. Prominent examples include recent Russian documents like “The Fundamentals of State Policy of the Russian Federation in the Arctic until 2035” (Russian Government, 2021) and “The Strategy of Development of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation and National Security until 2035” (Russian Government, 2021a).

One practical response to this situation would be to restart the Arctic Chiefs of Defense Staff Conferences that took place in earlier years but were cancelled at the end of 2014 during the Canadian Chairmanship of the AC in the wake of disagreements between Russia and other AC members regarding the situation in Ukraine. As in the cases of the Arctic Coast Guard Forum and the Arctic Economic Council, the basic idea underlying this suggestion would be to enhance the Arctic governance family by creating a body not formally a component of the AC but able to interact with the council in addressing matters of common concern. Gatherings of the armed forces chiefs to address Arctic matters of common concern would not have the authority to make binding decisions about matters relating to military security. But by providing a regular channel for issue-specific communication and cooperation, such a body could play a constructive role in avoiding misunderstandings arising from the securitisation of the international discourse relating to Arctic affairs and devising informal codes of conduct designed to minimise the risk of accidental and unintended clashes. Supplementing but not replacing the more formal procedures for dispute resolution set forth in the UN Charter, this informal arrangement could help to alleviate the atmosphere of tension between Russia and the NATO members of the AC that has had a chilling effect on efforts to address needs for governance regarding Arctic matters in recent years.

Reenergising the Arctic governance system

Russia regards the AC as an important mechanism for addressing regional matters of interest to the Arctic states. But changing conditions are posing growing challenges to the continued effectiveness of this mechanism. One such challenge arises from rising tension between promoting economic development in the Arctic and the looming threat of climate change that is eroding the resilience of Arctic communities. Another arises from the militarisation of the discourse regarding Arctic affairs that is threatening to replace the emphasis on cooperative activities within the AC with escalating activities reflecting the perceived imperatives of great-power politics. While the AC continues to make progress regarding a variety of specific initiatives, the result is growing concern about the continued validity of the 2013 Kiruna “Vision for the Arctic” asserting that “… the Arctic Council has become the pre-eminent high-level forum of the Arctic region and we have made this region into an area of unique international cooperation” (Arctic Council, 2013b).

How should we proceed at this critical juncture to ensure that the core of the 2013 vision remains viable during the 2020s? Over and above addressing specific items on the agenda of the AC, is this a suitable topic for consideration during the Russian Chairmanship? One appealing response to these questions would be to launch a high-level dialogue regarding ways to ensure that the AC and related bodies remain effective under conditions prevailing in the Arctic today. If this dialogue proved productive, it could provide the basis for organising an Arctic heads of state/government meeting (Berkman, Reference Berkman2010; Berkman, Reference Berkman2017) to reconfirm the value of the AC and the Arctic regime complex more broadly and to provide the council with a renewed mandate reflecting changes occurring over the last 25 years together with new mechanisms to strengthen the capacity of the council and related bodies to deal with needs for governance in the Arctic during the 2020s. Ideally, such a meeting could take place during the first half of 2023, forming a capstone on the second Russian Chairmanship of the AC.

Financial support

The preparation of this article was supported in part by US NSF Award 1660449 – Belmont Forum Collaborative Research: Pan-Arctic Options: Holistic Integration for Arctic Coastal Marine Sustainability.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.