Introduction

In 1845, the Franklin Expedition left England to seek a Northwest Passage through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The expedition was under the overall command of Sir John Franklin, with Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier RN and James Fitzjames RN commanding H.M.S. Erebus and Terror, respectively. Initially on board the two vessels were 134 men, who were equipped with provisions intended to last at least three years. Aside from two whaling ships which saw Erebus and Terror in Baffin Bay in the summer of 1845, no Europeans ever saw the crews alive again (Cyriax, Reference Cyriax1939). In 1848, after no news or contact, the British Admiralty and others began to organise search missions to learn the fate of the expedition. In 1851, the first evidence which provided frustrating little information came with the discovery of the expedition’s 1845-1846 overwintering camp at Beechey Island, and a camp site Cape Riley off the Southwestern coast of Devon Island (Hansen, Reference Hansen2010). In 1854, Dr. John Rae learned from the Inuit that the expedition had met with disaster sometime prior near the mouth of Back’s Fish River and that many of the men may have resorted to cannibalism to avoid starvation (Rae, Reference Rae1889).

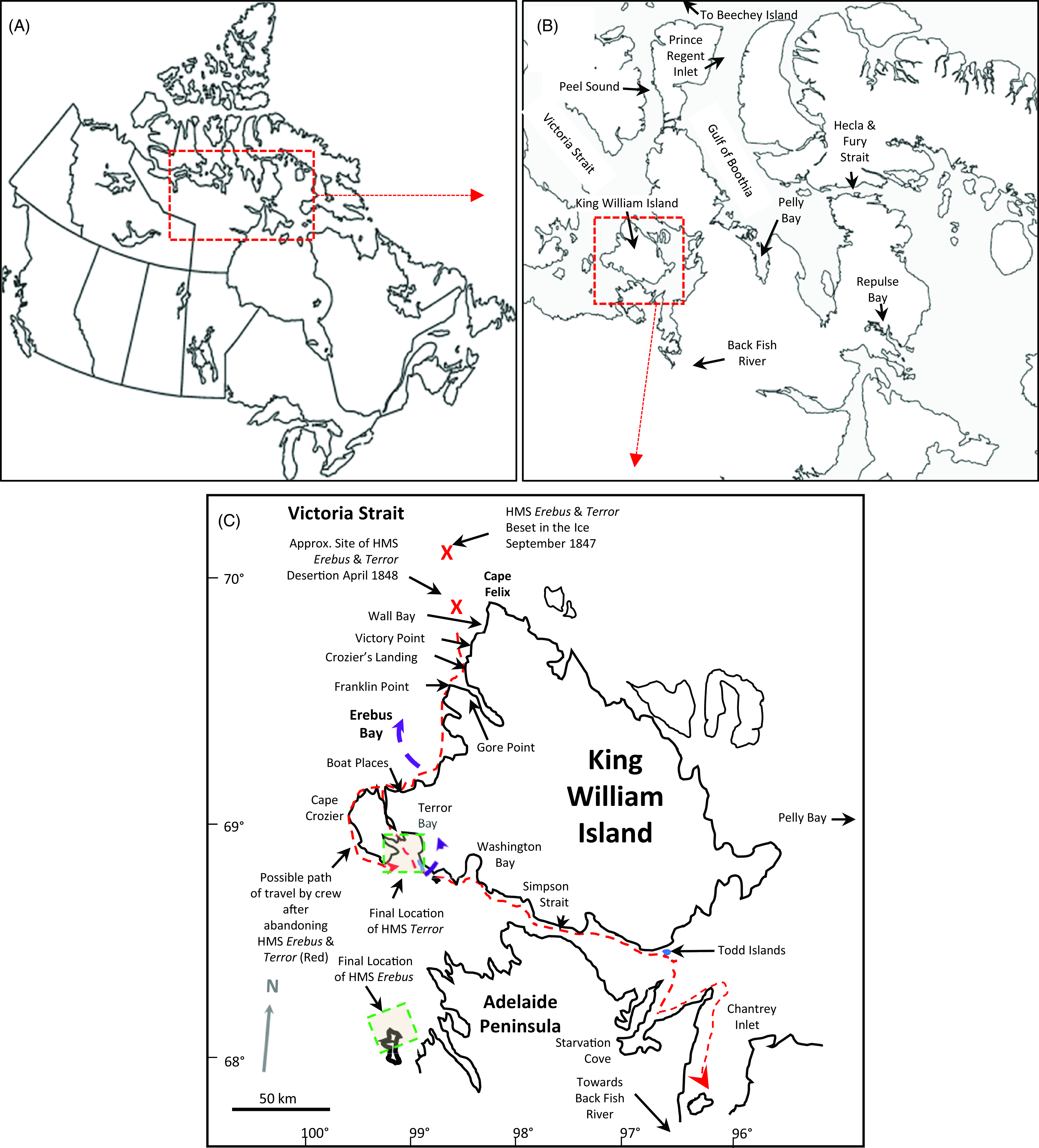

It was not until 1858 that a search party outfitted by Franklin’s wife Jane Franklin, and commanded by Leopold McClintock, found traces of the expedition on King William Island (KWI) and at Backs Fish River. Included in these discoveries were notes left in stone cairns by the Franklin Expedition at Gore Point and near Victory Point, KWI (M’Clintock, Reference M’Clintock1860) (Figure 1). It is from these notes made in 1847 that many of the details we now know relating to the expedition’s fate were learned. Initially, the crews over wintered at Beechey Island, and presumably in the spring of 1846, proceeded south through Peel Sound where they became trapped in the ice of Victoria Strait in 1846 (Figure 1). In the spring of 1847, the expedition sent out exploration parties which deposited the Gore Point and Victory Point notes. In 1848, the Victory Point note was recovered by the expedition and an addendum was added to the 1847 content of the note. It is in this addendum where it was learned that Sir John Franklin had died on June 11, 1847. The addendum also indicated that in April of 1848, the crews deserted the ships with the intention of reaching Back’s Fish River (Figure 1) (M’Clintock, Reference M’Clintock1860). From there we do not know where they intended to travel.

Figure 1. Maps of areas mentioned in the Jamme Report (Jamme, Reference Jamme1928). (A) Map of Canada showing the location of the Arctic coastal areas highlighted in the Jamme Report. (B) Hall’s area of activity and (C) King William Island areas associated with the Franklin Expedition described in the Jamme Report and approximate locations where HMS Erebus and Terror were discovered. Red dashed arrow indicates possible routes of travel to Backs Fish River, and purple arrows indicate possible return to the ships.

In the 1860s, Charles Francis Hall, an American, organised two expeditions to seek further answers as to what happened to the Franklin crews. His goal was to secure documents and relics, and if possible, rescue of any potential survivors (Nourse, Reference Nourse1879). During the second expedition (1864-1869), Hall made several attempts to reach KWI from his base near Repulse Bay, Nunavut, Canada. Hall wrote extensive notes on his travels and recorded many ethnographic observations. Critically, Hall recorded much of what he learned relative to the Inuit interactions with European explorers (Nourse, Reference Nourse1879).

Ultimately, Hall’s expedition was responsible for providing two reports which suggests that significant structures were established on the Western coast of KWI built by the Franklin Expedition. If the sites exist, reputedly they are either burial sites or repositories of expedition documents. The first of these reports was collected in June 1866, when Hall met an Inuit hunter named Sŭ-pung-er from Pelly Bay. Sŭ-pung-er reported that four years prior, he and his uncle had scoured the Western coast of KWI for resources including wood and metals abandoned by the Franklin Expedition, presumably in 1862 (Woodman, Reference Woodman1991; Woodman, Reference Woodman1995). Sŭ-pung-er reported that the structure they found was lined with stones, covered by large stones and had a “pillar” or “stick” which marked the location of the structure, which was seen from the shoreline (Gross & Taichman, Reference Gross and Taichman2017; Taichman, Reference Taichman2023). During Hall’s interactions with Sŭ-pung-er, Hall negotiated with Sŭ-pung-er to provide food and transport for Hall to visit the vault(s) site at a later date.

In 1867, Hall negotiated with captains of the nearby whaling fleet to hire several men to hunt and prepare provisions for his envisioned 1868 spring trip to KWI (Nourse, Reference Nourse1879). These whalers included Peter Bayne from Nova Scotia, Patrick Coleman of Dublin, Frank Laylor of Bangor, Maine, John S. Spearman of Quebec, Jose Francis from the Azores and Antoine of uncertain origins (Hall, Reference Hall1866; Loomis, Reference Loomis1971). While preparing for his 1868 trip to KWI, Hall learned that there might be Franklin survivors near the Hecla and Fury Strait (Nourse, Reference Nourse1879). Hall left most of the whalers near his Repulse Bay base camp and travelled to where he believed he would find these so-called survivors. When he returned to his base camp, he learned that Bayne and Coleman had met and interviewed an Inuit family from Pelly Bay who had had interactions with the crew of the Franklin Expedition (Harper, Reference Harper2007a,b). Most notably, the Inuit reported that they had witnessed a burial of a high-ranking officer, possibly Franklin himself: “that one man died on the ships and was brought ashore and was burled on the hill, near where the others were buried; this man was not buried in the ground like the others but in an opening in the rock” and his body covered with something that, “after a while was all same stone” and “many guns were fired”(Burwash, Reference Burwash1931).

Soon after arriving back at his base, Hall for reasons which remain unclear, alleged that Coleman was in the process of staging a mutiny (Harper, Reference Harper2007a,b). In a moment which Hall later expressed remorse, Hall shot Coleman. Coleman ultimately died of his wounds two weeks later, and almost as soon as the whaling ships returned to the area, the hired men abandoned Hall and his cause. The information that Bayne gained from the Inuit in 1848 remained undisclosed for many years. It was not until 1913, when it was reported that Bayne had purchased the schooner Duxbury in which he intended to head back to KWI in search of the site which he had learned about ~45 years earlier in 1868 (“Hunt for Franklin’s body planned.,” 1913, April 26.; “A Septuagenarian Arctic Explorer,” 1913). Whether Bayne ever made that trip remains unknown.

Bayne died in 1926. Sometime prior to Bayne’s death, he became acquainted with George Jamme. Jamme likely met Bayne doing geological survey work as a mining engineer in Nome Alaska. In 1928, Judge TW Jackson of Vancouver tried to sell the details of what Bayne learned pertaining to the Franklin Expedition to the Canadian Government. It appears that Jackson was serving as Jamme’s agent in brokering a deal for the document. How Jamme and Jackson became acquainted remains unknown. The details of the Bayne testimony are frequently referred to as the “Jamme Report,” which served as part of the justification for the Canadian Government to send Lieutenant L.T. Burwash to the Canadian Arctic between 1925 and 1930. Burwash, using a float plane, landed near Victory Point to search for the grave/vault sites (Burwash, Reference Burwash1931). Unfortunately, his search did not identify any relevant site(s). In 1931, Burwash wrote a report entitled “Canada’s Western Arctic: Report on Investigations in 1925-26, 1928-29, and 1930 (Burwash, Reference Burwash1931).” Included in this report are excerpts of the Jamme Report included in an appendix (appendix C). However, the entirety of the Jamme Report was never widely distributed (Jamme, Reference Jamme1928).

Given that there are only two major reports which suggest that a grave or vault-like structure was established by the Franklin Expedition on KWI, any detail pertaining to the site(s) is of value (Hall, Reference Hall1866; Jamme, Reference Jamme1928; Loomis, Reference Loomis1971). Individuals have argued that the site does not exist (Cyriax, Reference Cyriax1969), while others (including the author) have speculated that the site does exist, and it is possible that the Bayne and Sŭ-pung-er sites are the same, but represent observations made at different times (Gross & Taichman, Reference Gross and Taichman2017). If these observations were of one site, the Inuit who interacted with Bayne likely observed a burial sometime between 1847 and 1848, and Sŭ-pung-er likely observed the site between 1859 and 1861, when it was no longer intact. Despite the differences of opinions, many searchers have sought to locate the site(s), and the search continues to this day (M’Clintock, Reference M’Clintock1860; Wright, Reference Wright1959; Klutschak, Barr, & Schwatka, Reference Klutschak, Barr and Schwatka1987; Beattie, Geiger, & Tanaka, Reference Beattie, Geiger and Tanaka1992; Woodman, Reference Woodman1995; Gross, Reference Gross2012; Stenton, Reference Stenton2014; Kamookak, Reference Kamookak2017; Gross, Reference Gross2018; Coleman, Reference Coleman2020).

Given the importance of the Jamme document in the quest to learn what happened to the Franklin expedition and the validity of a cemented vault or grave, the Jamme document is replicated in the appendices in their entirety. The purpose of this communication is to present the Jamme report in its entirety along with a critique so that scholars in the future may have this tool if a vault or grave site is found.

Materials and methods

Beginning in August 2017, inquiries were made to several Libraries and Archives in Canada to request information on their holdings and for information on George Jamme, Judge TW Jackson or Peter Bayne. On April 1, 2022, a scanned copy of the original Jamme Report of 1928 was received from the Departmental Librarian, Corporate Information Management Directorate, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. Due to the length of the document and to present the Jamme Report as a whole, the report is presented as in the Appendix 1.

The scanned copy included a title page, a letter, an outline of the history of the Franklin Expedition and an account of Bayne’s experiences pertaining to the Franklin expedition and a discussion. Included in the scan were three sketches showing “the location of King William Island and Repulse Bay and the probable course taken by the Franklin expedition” which was not included in Burwash’s 1931 report in Appendix C (Burwash, Reference Burwash1931), a map intending to show the course taken by the crews after their abandonment of the ships as well as graves, relics and cairns. Finally, a sketch was included made by Jamme “from memory of a map Captain Bayne had among his papers, but which cannot be located now” which was labelled in the report as the probable location of Franklin’s tomb (Burwash, Reference Burwash1931).

The materials were transcribed in their entirety and are presented in Appendix 2. Materials which are extracted from the Jamme Report which appear in Burwash’s 1931 “Appendix C” are underlined in Appendix 2. Materials which are presented in the Burwash document which do not match those in the Jamme report are indicated in [squared brackets]. Source materials which contain spelling or grammatical errors are denoted through the use of sic in squared brackets (e.g. [sic]), rather than replacing the error. At several points in the manuscript, Jamme used several asterisks in the middle of lengthy paragraphs. These asterisks are transcribed, but for clarity, the passages are broken into separate paragraphs.

There are comments in the Jamme Report pertaining to race which are transcribed as presented for historic purposes. The comment “It was one of those great episodes in human affairs that shows the Anglo-Saxon to be the superior race” is racist, does not reflect the authors’ sensibilities and is not condoned.

Discussion

The search for the Franklin Expedition has fascinated experts and the public for generations (Potter, Reference Potter2016). In 1859, the first concrete evidence regarding the fate of the expedition was found by Lieutenant W.R. Hobson R.N., who, under the command of Captain Francis McClintock, led a sledge party to KWI and found a note in a cairn near Victory Point, KWI (M’Clintock, Reference M’Clintock1859). That document, often referred to as the “Victory Cairn Note,” was a standard naval message form to be filled out in transit and deposited at sea, or in cairns, at prominent points of land. Two brief messages were identified. The first written in May of 1847 indicated the expedition had over wintered at Beechey Island in 1845-1846 and that in September 1846, the ships had become locked in the ice to the Northwest of KWI. This 1847 message did not indicate any other problems, but was deposited in the cairn by an exploration party headed by Lieutenant Graham Gore, consisting of two officers and six men, which had left the ships on Monday, 24th May 1847.

The second Victory Point Note message of 1848 struck a different tone. Written in the margins of the first note, the message stated that Sir Franklin had died on June 11, 1847, and on April 22, 1848 the men, had deserted the Erebus and Terror and were headed to Back’s Fish River under the command of Captain Francis Crozier. After Back’s Fish River, it is not known where they intended to travel. No other document found to date has provided more insight into what happened to the crews. Specifically, did the crews return to their ships and sail them further South? How long did the crews survive and was Crozier amongst the last survivors as suggested by Hall (Hall, Reference Hall1866)? Did any of the critical ship logs and papers survive? And most germane to the current work, did they construct a site or sites on KWI to deposit documents, or was it a burial site of Sir John Franklin or another high-ranking officer? The answers to these questions remain unanswered.

In part based on Inuit testimony, in 2014 the wreck of HMS Erebus was located near Wilmot and Crampton Bay, on the Western coast of the Adelaide Peninsula, Nunavut, Canada (Figure 1). In 2016, Terror was located in Terror Bay on the Southeast coast of KWI. Like Erebus, the discovery of Terror was also partly based on Inuit testimony (Figure 1). In 1866, Charles Hall received testimony from a Pelly Bay Inuit named Sŭ-pung-er which suggested a site had been constructed by the Franklin crews on the Northwest coast of KWI. From Sŭ-pung-er’s description, Hall believed the site contained documents or that it may have been the grave of Sir John Franklin (Hall, Reference Hall1866). In 1868, members of Hall’s expedition including Peter Bayne reportedly learned from Pelly Bay Inuit that the Inuit had interacted with members of the Franklin crews, presumably during 1846-1848 (Harper, Reference Harper2007a; Gross, Reference Gross2012; Gross, Reference Gross2018; Jamme, Reference Jamme1928). Critically, the 1868 information reportedly indicated that many sick men were at a shore-based camp, some men were buried behind the camp, and one man died on the ships and was brought to shore, but was not buried in the ground like the others. This man was placed in an opening in the rock and covered with a material that turned “all the same stone” (Jamme, Reference Jamme1928; Burwash, Reference Burwash1931). The testimony also reported that “many guns were fired” suggesting a military burial (Jamme, Reference Jamme1928; Burwash, Reference Burwash1931). The 1868 testimony further suggested that there may have been several smaller sites constructed nearby.

This 1868 testimony is often referred to as the “Bayne Testimony.” It was first published as an extraction of a report written by George Jamme and sold to the Canadian Government (Jamme, Reference Jamme1928; Gross, Reference Gross2012). The Jamme Report has never been widely distributed but was published in extracted form by Burwash in 1931 as part of a comprehensive summary of his work in the territory (Burwash, Reference Burwash1931). Given that the Jamme Report remains one of the few, purported eyewitness accounts of the activities of the Franklin Expedition it remains of great value at least until additional new information is extracted either from the ships themselves, or new sites are discovered. Further, the report is significant, in and of itself, as it suggests the existence of a grave or vault(s) of potential documents. If the report is reliable, it could corroborate the 1866 testimony reported to Hall by Sŭ-pung-er (Hall, Reference Hall1866; Gross & Taichman, Reference Gross and Taichman2017). Therefore, a complete reporting of any Inuit testimony is important (Jamme, Reference Jamme1928).

So what did we learn from the full Jamme Report that was not already conveyed in the Burwash Report (Burwash, Reference Burwash1931)? First, we learn greater details as to how the Jamme Report was generated, and the relationship between Judge TW Jackson of Vancouver, George Jamme, and Peter Bayne. From the introductory letter, it is learned that Jackson was serving as Jamme’s agent in brokering a financial deal for the document with the Canadian Government. We also learn that Jamme had become acquainted with Bayne while performing geological survey work in Alaska. We learn that the report contained a history of the Franklin Expedition and an analysis of Hall’s exploits. These new and substantial details provide a broader understanding of the report, which previously had been limited to the details pertaining to the Inuit observations of the Franklin crews. While these details, in and of themselves, do not assist us in determining the validity of any of the contents, they do provide a more robust picture.

We also learn that the report was not generated in a vacuum. Jamme reported that he had read extensively on the subject of the Franklin Expedition, as well as “Hall’s traits and personality so as to make clear his actions and attitude. Bayne, of course, had many things to relate of his adventures in connection with this employment, some of which were relevant, others not…” (Jamme, Reference Jamme1928). Jamme related that in his discussions with Bayne, he believed that he had triangulated the details with known facts to sufficiently establish the truth of the Bayne story. It is notable that Jamme was aware of this criticism given the time which had transpired between when Bayne had theoretically received the Inuit testimony (1868), and when Jamme became acquainted with Bayne, likely between 1810 and 1820s. Yet he also expressed some doubt in the stories when he stated “The labor in the matter was to substantiate these bare facts by historical data. This latter the writer has done as far as it seems possible to go. The evidence is not conclusive, but it is sufficient to be considered as reasonable.”

The 1928 Jamme Report proposed that the site reported in the Inuit testimony was that of a high-ranking officer. Bayne clearly believed this to be the case as was stated in several newspaper articles first appearing in 1913 (Hunt for Franklin’s body planned, 1913, April 26.; “A Septuagenarian Arctic Explorer,” 1913). These articles reported that Bayne purchased a schooner in preparation of a trip to KWI. Jamme likely based his belief that the site was a grave and that it represented Sir John Franklin himself, as he wrote “If the three members of the crew who died during the first winter at the Beechey Island camp were buried on land, and if the other members of the crew who died while the ships were fast in the ice off King William Land were buried on the land, it is more than likely, then, that their leader would also be buried on the land.” The possibility that there was sufficient manpower and the crew were in sufficient health to bring a body from the ship’s known position to land was possible given that the Victory Point document of 1847 indicated, “Sir John Franklin commanding the expedition. All well.” As the weather was favourable enough in May 1847 for exploration parties to be sent out, a burial sometime after the reported death of Franklin in June 1847 on shore, was feasible.

There are several issues pertaining to the burial which merit speculation as to the Jamme Report’s veracity. First is the notion that a high-ranking officer, possibly Franklin himself, might have been buried with a different formality than other officers. At the time of his death, the officers and crew of the Erebus and Terror likely retained hope for the success of their Northwest Passage mission. In fact, many speculate that Lieutenant Gore likely had made the first transit of the Northwest Passage prior to Franklin’s death, based on the information obtained from the Victory Point note. Therefore, it is possible that the expedition’s crew would have wanted to provide a fitting memorial to an admired leader (Potter, Reference Potter2022) and who had led the expedition which had finally completed the Northwest Passage. However, there is no evidence that it was Franklin, or for that matter, any other officer who was buried apart from the others. The author is not aware of similar constructions being made to honour other British Naval officers on previous expeditions. The more traditional course of action would have been to bury a body at sea through the ice near the ships (Zorn, Reference Zorn2023). Another option would have been the approach used on Nelson’s body after the Battle of Trafalgar, which was to put his body in a barrel of alcohol for return to Britain for burial (Zorn, Reference Zorn2023). It is also possible that the crews sought a temporary cache for the officer’s body, rather than a permanent entombment, with the intention of eventual repatriation for a more fitting burial later. In which case, the establishment of an elaborate tomb, as insinuated by the Inuit, might have been excessive.

Likewise, if it was Franklin’s body entombed in the structure, we would want to know whether he was buried with his Guelphic Order medal. It is possible that the Franklin crews had chosen to transport the Guelphic Order with them for delivery to Lady Jane at some later date given its significance. Such that the medal was subsequently among the relics the Inuit found amongst the dead on KWI or near Back’s River. If Franklin was buried with the medal, then the vault must have been broken into. Unfortunately, the providence of the Guelphic Order, which was recovered by Rae, is unknown other than that Rae recovered it in trade from the Inuit he encountered in 1854 (Rae, Reference Rae1889).

A further issue which raises questions in the Jamme Report is the detail of a large number of burials behind a camp where ships boats normally come in, at or near Victory Point, Cape Felix or any prominent point on the West Coast of KWI. To date, no such camp or burial site has been located. The lack of a mass burial site might be explained if the crew that were lost did not die near the ships. However, the Jamme Report indicates that an officer guided the Inuit informant to view a camp near shore from the ships. Given the reported location of the ships in the Victory Point note, this would only have been possible if at some point the ships had been closer to shore, possibly before the ships became beset in the ice in 1846, or sometime after the 1848 “desertion.” While these observations do not negate the veracity of the Jamme Report, they do raise speculation. However, in Hall’s journals there are reports of Inuit being told to avoid shore-based camps allegedly associated with the Franklin Expedition (Hall, Reference Hall1866).

The Jamme report also proposes the covering of the site “was probably not Portland cement, as “cemented tomb” would suggest, but a mixture of tar and sand. All ships carry tar for calking purposes which, when mixed with sand and cooled, would become hard as described.” If the “cemented” vault is real, it is possible that the materials used in its construction would have been made of resin or pitch with sand and stone, which would over time become “one stone.” Alternatively, it was known by the 1830s that the primary raw materials used to make cement are limestone, clay or shale. The process of making a cement involves heating a mixture of these raw materials to a very high temperature. It is important to note that there are different types of cements, and variations in the raw materials and manufacturing processes can produce different types of cement with varying properties. While the area near where the ships were beset on KWI has abundant raw materials for the construction of a cement, fuel to heat the materials would have been scarce unless coal from the ships had been utilized. The heated materials would then have had to have been ground into a fine powder, transported to the site or fabricated in situ. Unfortunately, there is little evidence that cement was made by the expedition. Nor is there evidence of kilns having been made to heat the raw materials on either ship or in the surrounding areas although the possibility remains. Several Inuit sources suggest the finding of the remains of cast-iron stoves, although their utility to generate cement is highly doubtful (Hall, Reference Hall1866; Stenton & Park, Reference Stenton and Park2020).

A pertinent aspect of the vault story is whether Hall knew of the testimony obtained by Coleman and Bayne. Jamme insinuates that Hall did when he states that “It is not known whether Hall queried the local natives as to the recitals of the Boothia natives; presumably he did. In his records he mentioned cemented vault in which papers have been placed but in no way mentions the burial of Franklin – either in the deep or on the land” (Jamme, Reference Jamme1928). Whether Hall sought additional knowledge from the Inuit regarding this testimony is not known. It is known however that Hall did know of the Bayne testimony based upon a letter dated March 1868 (Kilmer, Reference Kilmer1868). This letter written by Hall’s friend Captain C.B. Kilmer of the whaler Ansel Gibbs, was written to Hall’s sponsor Henry Grinnell. Kilmer wrote that the story reported by Sŭ-pung-er is inaccurate; “The story about the natives who saw ‘some white men carry a dead body on shore’ etc, and that said body was supposed to be Sir John, is all very nice in theory, but there is not one word of truth in the whole thing. I am thoroughly posted in this regard to the statement made by the natives, besides Mr. Hall and myself have discussed the subject a hundred times” (Kilmer, Reference Kilmer1868). Sŭ-pung-er’s testimony does not include carrying a dead body to shore; therefore, it can only have been obtained in connection with the testimony related to Bayne and Coleman in 1868.

An aspect that is new to the narrative is that when Bayne probed the relationships between the different “tribes or settlements” in an effort to learn whether it was safe to travel to KWL, he learned that the individual he was conversing with “knew of Hall’s meeting with the Pelly Bay native, and of the cause of the turning back, and as he expected to make the King William trip in the following spring, he very naturally wanted to know what to expect on the way.” This is likely a reference to Sŭ-pun-ger’s meetings with Hall in 1866. Sŭ-pung-ger, and other Pelly Bay natives met Hall on his initial attempt to reach KWI. We have speculated that the Sŭ-pung-er and Bayne testimonies relate to the same structures, observed at different times (Gross & Taichman, Reference Gross and Taichman2017). If so, the Bayne testimony relates to events taking place around 1846-1848, and Sŭ-pung-er’s in 1862-3, where someone is buried (Bayne testimony), and subsequently, the site is broken into (Sŭ-pung-er’s testimony).

One of the most poignant details which is learned from the full Jamme Report are details surrounding the translation of the testimony to Bayne and others. We learn that a young Inuit girl who had been with Bayne on his two prior hunting trips during 1867-1868 assisted in the process, “What was desired was that the local natives should get a full understanding, in their own language, of the new features of Franklin’s Expedition which these Boothia natives had to tell. Bayne could understand most of the things that were said. But there were occasional expressions he had never heard before; and, when he got stuck the young girl would generally be able to tell him what was meant (Jamme, Reference Jamme1928).” Unfortunately, we have no indication from contemporary Hall’s notes that Bayne was proficient in communications with the Inuit. This is relevant given the details the Bayne report relates and the uncertainty is underscored by his reliance on a young Inuit female companion for translation, which raises the possibility that some of the information he acquired may have been misinterpreted or inaccurate. It is also of interest to note that the “Pelly Bay natives were on their way to Wagner Inlet as they, they wanted to try and get powder and shot from the whalers. They had with them a single-barrel muzzle-loading, small-bore gun which they said they had secured in trade from another native who had picked it up on King William Land.” So far as is known, the only site on KWI where rifles were left by the Europeans was at the “Boat Place,” on the Southern Coast of Erebus Bay, KWI (M’Clintock, Reference M’Clintock1860). Further, we learn that Bayne and Coleman devised a plan to prevent the Inuit from learning how to effectively operate the firearm in the event it would be used against them in the future. All of these communications were likely translated by the young Inuit woman and her family. Her ability to serve as an accurate translator is not known.

A central aspect of the credibility of the Jamme Report hinges upon the trustworthiness of Peter Bayne. It is noteworthy that Bayne related his story to Jamme decades after the events of C.F. Hall’s expedition. While this raises significant doubts regarding the accuracy of Bayne’s recollections of those events, there are also several contemporary reports in newspapers which impugn Bayne’s character. There were allegations that Bayne deserted his family during a prolonged absence while whaling which led to his divorce (“An Enoch Arden Case. A New Light on a Seattle Sensation. Treachery of Mrs. Bayne. Death Cuts Short Her Sinful Career – A Motherless Babe Left,” An Enoch Arden Case, 1890). There is also a report that Bayne was arrested for teaching the natives how to make alcohol (Gross, Reference Gross2018). To date, however, there is no indication that Bayne was convicted. These events suggest that while Bayne was a complex individual, his trustworthiness remains unknown, but is a central critique of the Jamme Report.

A significant and frequently cited criticism of the Jamme report revolves around its sale to the Canadian Government. Allegedly, Bayne confided in Jamme about the vault’s story and his desire to search for it. Bayne was likely in his 70s when this occurred perhaps making a trip to King William Island less likely. It is known that Bayne possessed a map indicating the site’s location, but that map was lost, and the one included in the Jamme Report was reconstructed from memory by Jamme. Following Bayne’s death in 1926, Jamme passed the story to Judge T.W. Jackson of Vancouver. In 1929, Jackson attempted to sell the document to the Canadian Government reportedly for twenty-five thousand dollars. The Department of the Interior reluctantly paid one thousand dollars for the document, and in 1930 Major L.T. Burwash, was tasked to follow up on the story by arial and land-based surveys in the vicinity of Victory Point. Regrettably, Burwash did not find any evidence as to the credibility of the report. Together, the sale of the document and the financial motivations involved raises questions as to the integrity of the information. In all of the copious notes that Hall made during his time in the Arctic, precious little is recorded during the period between when he returned from his trip from Hecla and Fury Bay in 1868, until after Coleman died of wounds inflicted by Hall (Harper, Reference Harper2007a, Reference Harper2007b). In Hall’s existing notes, there is no direct record that Hall ever heard what Coleman and Bayne had learned, apart from the Kilmer letter (Kilmer, Reference Kilmer1868), and therefore, the Jamme Report remains the sole document which records what the whalers learned from the Inuit. In fact, Hall’s notes almost appear as if they had been sanitised as Hall may have believed he would face murder charges upon his return to the United States. In reality, though Hall was accused of murdering Coleman in cold blood, the Canadian Government considered Hall’s expedition under American jurisdiction, and the Americans did not want to prosecute a crime committed on Canadian territory (Harper, Reference Harper2007a, Reference Harper2007b). As a result, Hall was never tried for Coleman’s murder.

In summary, the current report adds colour to what may have happened to the Franklin Expedition, and the crew member’s interactions with the indigenous populations. What we do know pertaining to the fate of the Franklin Expedition after it departed England in 1845 is predominately derived from the archaeological record and from the Victory Point Note. Charles Francis Hall, during the 1860s went to the Arctic in search of survivors, papers and relics. Through Hall’s expedition, Inuit testimony provided a clearer picture of the fate of the crew and established two testimonies which reputedly describe either an underground vault or burial site. The first testimony was recorded by Hall himself was obtained from Sŭ-pung-er in 1866. Interestingly, Sŭ-pung-er reported that a pillar had stood over the site, and he had taken it down for want of building materials. A model of the pillar was recently located (Taichman, Reference Taichman2023). The second testimony was obtained from Pelly Bay Inuit during Hall’s absence by members of Hall’s support team, specifically Peter Bayne, in 1868. The second testimony was eventually sold to the Canadian Government in the form of a report written in 1928 by George Jamme. Until now, only abstracts of the Jamme Report have been made available. This paper provides the Jamme report in its entirety, with critical analysis, so that future scholars may have this tool in the event the vault or grave site is identified.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247423000347.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks their families and friends for enduring hours of banter regarding the Franklin Expedition and the Northwest Passage. The author is grateful to Susan Taichman-Robins (Philadelphia, PA, USA) and Tom Gross (Hay River, Northwest Territories, Canada) for their helpful discussions and for their ongoing collaborative activities. Mr. Joe Hursey and staff, Charles Francis Hall Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History (NMAH), Smithsonian Institution, were helpful in providing context to the Hall papers. The author also thanks the unnamed reviewers for their assistance in improving the paper.

Competing interests

The author has no relevant conflicts of interest pertaining to this work.