Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 December 2020

Widsith is the only Old English poem concerned exclusively with a scop and Deor the only one specifically attributed to a scop. In both a scop is represented as speaking, and in each he tells something of what had befallen him—Widsith, the far-wandering and richly rewarded scop, and Deor, the court scop who had lost his long-held and lucrative post to a rival. These poems are therefore similar and also the only ones which give us a first-person account of a scop's career. It is usually for the sake of the information thus provided that the poems are discussed together. This information is precious little, however, and some of it is dubious.

1 The standard editions of both poems and the ones cited here are Kemp Malone's Widsith, revised ed. (Copenhagen, 1962) and Deor, 3rd ed. (London, 1961).

2 In Widsith he is called a gleeman (glēoman), a term more or less synonymous with scop. In Beowulf Hrothgar's scop is referred to also as his glēoman.

3 How formidable this task has proved is reflected by the fact that in Malone's edition the glossary of names (pp. 126–216) occupies almost as much space as all the rest of the work.

4 This is obvious in Widsith, where the presence of the two kinds of matter has long been recognized. In Deor, however, the fictional and traditional matters are less clearly distinguished, for—as I shall try to show—the poet deliberately but cleverly blurred the distinction between the two.

5 For a more detailed analysis, revealing further instances of structural care, see Malone, pp. 27, 58–60, and especially 75–77.

6 A feature deriving no doubt from the formulas (ic wæs mid … and … sohte ic) in the name-catalogues. Why the poets who originally composed the catalogues used these formulas is uncertain—possibly to lend authenticity but more likely for no good reason at all, as is to be expected of poetry at the time when it was still being orally composed.

7 But see Morton W. Bloomfield, “The Form of Deor,” PMLA, ixxix (1964), 534–541. He believes a refrain is found also in Wulf and Eadwacer and in some of the charms. But because the repeated lines there, Ungelic is us (in W and E) and Ut, lytel spere, gif her inne sie (in the stitch charm), are not used to set off structural units consistently, I think it best not to call them refrains.

8 For this reason alone, it seems to me that P. J. Frankis' interpretation of Deor (Medium Ævum, xxxi, 1962, 161–175) must be rejected, for it requires that Deor and Wulf and Eadwacer be regarded, not as separate poems, but as parts of a single work.

9 On the meaning of mæg here, see Bloomfield's discussion, p. 536.

10 Or, as Malone puts it, “the final section … was in the nature of an afterthought or postscript” (p. 15).

11 A point vigorously expressed by Frankis: “Hitherto it has been assumed that the only connexion between the sections is one of casual association in the poet's mind. … it is hard to believe that the poem is entirely based on such an accidental train of thought” (p. 167). The connection which he tries to establish, however, is not much more satisfactory.

12 Lines 28–34 are discussed below.

13 The date and place of the composition of the poem are discussed in my paper, “The Story of Geat and MæÐhild in Deor,” Studies in Philology, lxii (1965), 495–509, where my main concern, however, is to try to explain the story.

14 As instances of actual misfortune, the poet's allusion to the Goths (see n. 30) is hard to justify and his allusion to the Mærings (n. 28) really impossible.

15 When the Heodenings flourished is unknown, but to the poet's audience it would have seemed a long time before.

16 “Widsith and the Scop,” PMLA, lx (1945), 623–630.

17 The italics and brackets are his; the footnotes and the dots indicating omissions are mine.

18 A torque worth six hundred shillings. Although the precise meaning here (ll. 90–92) is uncertain (see Malone, p. 48), there is no doubt about the fact that the torque was a “magnificent present” of “extraordinary value,” as R. W. Chambers says (Widsith, Cambridge, 1912, p. 26). He adds, “It would probably have been held ostentatious, and it would certainly have been imprudent, for a minstrel to wear treasure worth the price of his own life. Nobody but Eormanric, the possessor of fabulous wealth, could afford to give such an armlet to a singer.”

19 Wife of Eormanric.

20 Which French recognizes (p. 625) but construes as evidence that the poet was a scop—a conclusion I share but on other grounds.

21 Especially the torque received from Eormanric and also, I think, the ancestral land received from Eadgils. The question is not whether Widsith received the estate as his legal right (as Malone convincingly argues, pp. 48–50) or as a grant from his lord, but whether a scop might actually have possessed such an estate. I am dubious, for this estate, like the one Deor claims to have received, seems to me to be an exaggerated claim rather than a likely fact.

22 By adding “realistic touches,” as Malone (p. 112) characterizes the poet's “constant talk about gifts”—touches which I think are anything but realistic. Had it been the poet's wish to make Widsith seem true to life, there were many realistic touches he might have added—and would to God he had!—about the scop's craft and how it was actually pursued (cf. Ælfric's Colloquy).

23 In addition to “the only touch of wit in the poem” that Malone detects (p. 56) in ll. 125–126, there may be another in ll. 103–108. Here Widsith tells how he and Scilling burst out in song, presumably in thanks for a second torque given him by Ealhhild. This Scilling, uncapitalized in the MS, has always been puzzling and is variously construed as the name of Widsith's harp, of the harper playing his accompaniment, or of a fellow-scop joining him in a duet (see Malone, pp. 50–51 and 194, who somewhat doubtfully adopts this last view). Perhaps it is an attempt at wit, the poet intending scilling ‘shilling’ to signify (by synecdoche) the torque and wit scilling (we two, I and my torque) to mean “I, Widsith, thus rewarded by Ealhhild, burst out in song.” Worth noting is the fact that scilling occurs only once elsewhere in the poem, a few lines earlier, where (l. 92) it clearly means ‘shilling’ and is used in describing a torque (see n. 18). The only other possible trace of wit that I can detect is the name Widsith, which the poet may conceivably have coined not in sober acknowledgement of the scop's extensive travels but in wry amusement. Wit clearly was not the Widsith poet's forte.

24 Thus also French (see n. 20). Malone, however, believes he was a cleric (p. 112).

25 Unidentifiable because of our uncertainty about the date and place of the composition of Widsith. Malone can date it no more precisely than “the latter part of the seventh century” (p. 116). Though apparently inclined toward Mercia, he hesitates to assign it there or anywhere else because of the diversity of its dialect features (pp. 112–115).

26 See Malone, pp. 28–34 and 146–149.

27 My reasons for dating the poem thus are set forth in the paper mentioned above where I discuss the tale the poet is referring to and point out why this tale indicates that the poem is of Mercian provenance. My dating and localizing of the poem are conjectural, to be sure, but in the absence of contrary or better evidence I think they are tenable. Nonetheless, it may seem needlessly risky to assume, as I do, that the poet was Offa's scop rather than a scop, say, at some other court nearby, that of some petty king or noble subjugated by Offa. The risk is a calculated one, defensible as the simplest and, I think, the best among the various possibilities that might be conjured up. The crucial point, after all, is not that he is Offa's scop but that he is a scop seeking something from someone and doing so in a cryptic way that demands explanation.

Aside from my paper in SP, the only other recent attempt to date Deor is Frederick Norman's “Problems in the Dating of Deor and its Allusions,” Franciplegius: Medieval and Linguistic Studies in Honor of Francis Peabody Magoun, Jr. (New York, 1965), pp. 205–213. He favors a date somewhere between 700 and 850 (p. 208). Though evidently sharing my view that Deor is a begging poem (p. 212, n. 5), Norman does not elaborate on the matter.

29 As early as 774 he had styled himself rex Anglorum and rex totius Anglorum patriae. On Offa, see Sir Frank Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England (Oxford, 1943), especially pp. 216–217.

| We geascodan | Eormanrices |

| wylfenne geþoht; | ahte wide folc |

| Gotena rices; | þæt wæs grim cyning. |

| Sæt secg monig | sorgum gebunden, |

| wean on wenan, | wyscte geneahhe |

| þast þæs cynerices | ofercumen wurde. |

31 As Malone accounts for the difference (Widsith, p. 33).

32 My reasons for regarding Unferth as a jester rather than a court dignitary are explained in Speculum, xxxviii (1963), 267–284. Unferth is called a þyle, a term possessing various senses, among them (as gloss evidence clearly shows) ‘scurrilous jester’ (ibid., p. 268; cf. J. D. A. Ogilvy, PMLA, lxxix, 1964, 370–371). This sense is shared also by glēoman (as gloss evidence indicates—see pp. 281–282 of my Speculum paper) and by scop as well (as the citations indicate in Bosworth-Toller, An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, Oxford, 1898, 1921). For scop this was evidently the etymological sense, as is usually rather diffidently suggested, e.g., in Bosworth-Toller, but sometimes more positively asserted, e.g., in Walde-Pokorny, Vergleichendes Wörterbuch der indogermanischen Sprachen, ii (Berlin and Leipzig, 1927), 556: scop “Dichter (ursprgl. von Spottversen).”

The lexical evidence is thus quite clear that scop possessed the unfavorable sense ‘scoffing poet’ as well as the more favorable or neutral sense ‘poet.‘ Although this has long been recognized (cf. Reallexicon der germanischen Altertumskunde, i, 1911–13, 445), it has been ignored, scop (like glēoman and pyle) being accorded only the favorable sense that Deor, Widsith, and Beowulf have heretofore seemed to require.

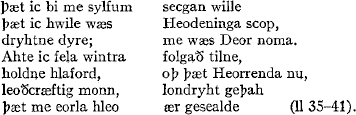

| þæt ic bi me sylfum | secgan wille |

| þæt ic hwile wæs | Heodeninga scop, |

| dryhtne dyre; | me wæs Deor noma. |

| Ahte ic fela wintra | folgaÐ tilne, |

| holdne hlaford, | oþ þæt Heorrenda nu, |

| leoÐcræftig monn, | londryht geþah |

| þæt me eorla hleo | ær gesealde (ll 35–41). |

34 Deor, like Widsith, is a name which the poet presumably coined, in this instance rather wittily, I suggest, deriving it from the adjective deore (used in the same line, where it appears, however, in its later West-Saxon guise as dyre) and thus calling attention to his former, more fortunate lot. This evidently is why he uses the past rather than the present tense. Line 37 accordingly means, “[I was] dear to my lord; my name once was Dear.” Nu (l. 39b) is probably an interjection rather than an adverb.

35 Which would account in part for the dialectal admixture found in most of the extant Old English poetry.

36 Its fullest and clearest expression is to be found in L. F. Anderson, The Anglo-Saxon Scop (Toronto, 1903). An M.A. thesis of only 45 pages and now completely outdated, it is still cited as the standard work on the subject. A few of Anderson's comments, all of them echoing earlier judgments of the same sort and echoed repeatedly since, are worth citing: “The poems Widsith, Beowulf and Deor's Complaint contain nearly all the information obtainable in Anglo-Saxon literature itself concerning the professional singer. … Widsith is … of the greatest value. It is an account composed originally by a court singer of his experiences in the practice of his profession” (p. 5). A passage there (ll. 50–55) “indicates quite distinctly that to have seen many lands, to have had a wide and varied experience was considered a qualification for the poet-singer's calling” (p. 27). “The scop held among the early Anglo-Saxons a position of honour. The simplicity of their social organization, the immediate relations in which one member of the tribe stood to the others gave the incumbent of this office a weight and influence which it is difficult to imagine” (p. 30). “The dignity and worth of the scop stand out in marked contrast to the disrepute of their degenerate successors of later times” (p. 34). “… the fact … that Deor, Heorrenda, and Widsith received grants of land favour[s] the opinion that the art of the ancient scop was richly rewarded” (p. 42). “[The scop] was esteemed by his contemporaries, not simply as the poet but also as the sage, the teacher, the historian of his time. His power of moulding public opinion secured for him marked consideration from the great and powerful” (p. 45).

37 It evidently began to flourish with the coming of the friars in the thirteenth century, when beg first entered into the English vocabulary.

38 I have found nothing of any worth on the subject.