One week into 2021, Epic Games had already made the headlines twice. On 3 January, the developer of the megahit game Fortnite, based in Cary, North Carolina, announced it was moving its headquarters across town to the Cary Towne Center, a 980,000-square-foot mall opened in 1979 and now mostly empty (Wagner and Eanes). Four days later, the company acquired RAD, a maker of game tools whose products are featured in every game being made today (Coldewey). The repurposing of the defunct mall was a widely applauded vote of confidence in the town of Cary. It was a sign that, even with the pandemic, all was well in the Research Triangle—the National Humanities Center; the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; and Duke University.

Epic Games is the purveyor of a fantasy world remarkably attuned to the pulses of the moment. Its resources are superabundant, but its ability to intervene in real time is the rule rather than the exception. The gaming industry is one of the few economic sectors to continue to flourish under COVID-19 (Smith). The industry often closely tracks current events, sometimes at considerable risk to itself. In April 2020, Animal Crossing, an open-ended game developed by Nintendo that allows players to live among animals and write their own scripts, was banned by China, apparently for lending support to the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong (Davidson). Ian Bogost argues in The Atlantic that this social simulation series is political, not escapist. Can this be said of games in general?

That question would come up again after the violence on the United States Capitol in January 2021, when commentators were struck by the “eerie parallels” between the riots and another game franchise, Tom Clancy's The Division (Kerridge). “There can't be many people who failed to find themselves transfixed by Wednesday's footage,” Jake Kerridge writes in the Telegraph. “And yet there is one demographic who may have watched the mayhem unfold with a slightly blasé sense of having seen it all before: gamers.” The Division is set in a divided America, brought low by a global pandemic and domestic terrorism. The first installment of the game, released in 2016, features medics in personal protective equipment struggling to stay afloat in an overwhelmed hospital, with the tagline, “They said it was just the flu, but it turned out to be something else entirely.” The Division 2, released in March 2019, shows the Capitol taken over by right-wing extremists known as the True Sons (short for the True Sons of Liberty), a well-trained, well-armed group of disaffected military personnel.

Epic's collision with history is not quite as dramatic, but it is hardly inconsequential. On 13 August 2020, in the wake of the congressional antitrust hearings on big tech, Epic's founder and chief executive officer, Tim Sweeney, filed two lawsuits, first against Apple and then against Google, for charging a thirty-percent fee on apps downloaded onto iPhones through the Apple Store (Griffith). Epic Games, valued at $17.3 billion, with 350 million registered players for Fortnite, isn't exactly a David fighting two Goliaths, but it is without question the underdog in these two cases. It had interim success in court, winning the dismissal of two of Apple's tort claims and the opinion from Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers that “[t]his is a high-stakes breach of contract case and an antitrust case” (qtd. in Hurtado).

Epic's decision to move into the Cary Towne Center and acquire RAD came in the midst of this legal battle—and, of course, the pandemic. With the acquisition of RAD, it becomes a company partly based in Kirkland, Washington; it has announced job openings in that city. For many of us, Kirkland rings a bell in one context: COVID-19. The first reported death from the virus in the United States occurred here, at the EvergreenHealth Medical Center, while the outbreak at the Life Care Center nursing home, eventually infecting one-sixth of the residents and staff, marked the official arrival of the pandemic. That coincidence could not have been a factor in Epic's decision to acquire RAD, but it is fitting that Kirkland is now part of a long-running, outcome-uncertain epic game. Something else might come of the pandemic. Like Cary, Kirkland is poised to write itself into a different script and go down in history in ways yet to be decided.

Nintendo and Epic have set a very high bar for the vital continuum between games and life. That continuum seems to be a key motivation as well for humanists throwing their hats into the ring. Patrick Jagoda, professor of English and cinema and media studies at the University of Chicago and the director of the Weston Game Lab, has long integrated games into his teaching for just this reason. His subgenre of game—alternate reality games, or ARGs—stretches the already elastic line between fiction and reality even further. Unlike commercial video games, played on specific devices such as phones, gaming consoles, or computers, ARGs claim the entire world as their stage, telling stories across a variety of platforms, including websites, video, live theater, e-mail, social media, posters, and phone calls, and layering itself into different public and private infrastructures to maximize the chances for interaction in each. “This is not a game”—a manifesto taken from The Beast, considered by many to be the first ARG—confers on these staged encounters the gravity of actual events. Players are encouraged to look into real-life problems, propose solutions, and share information with other players as each writes a different script.

Immersive games can easily become addictive, and Jagoda has exploited this dynamic to get students immersed in existential threats now facing us. In Terrarium, for example, a climate change ARG designed for the 2019 first-year orientation at the University of Chicago, incoming students were asked to start brainstorming about an online quest narrative before they arrived on campus, so that they were primed to forge ahead with the game as soon as the fall semester began. Among the dozens of ideas proposed were tree-shaped, bioluminescent bioreactors that would provide light and food on campus; a low-cost clothing swap program to reduce textile waste; and a strain of bioengineered carbon-sink plants. “This project isn't about immediate outcomes,” says Jagoda. “It's about getting students into different zones of perception, attention and motivation,” so that “they can extend such collaborative and imaginative energy across their four years here” (qtd. in Ehret).

Even without the $17.3 billion war chest Epic Games has at its disposal, humanists can come up with some decent productions. These are urgently needed now to reconnect communities dispersed and disoriented by the pandemic. Working with the Fourcast Lab, Jagoda came up with two ARGs designed for undergraduate students, graduate students, staff members, and alumni, along with high school students at the University of Chicago Lab School.

The first game, A Labyrinth, was launched on 6 April 2020, attracting 3,500 participants organized into 73 teams. Through a Twitch livestream platform, players were once again immersed in a quest narrative layered onto the university campus (fig. 1). This one featured the Minotaur, or the Taur in-game. Unlike the menacing creature in Greek mythology, this Taur was shy and had lost its way, needing help to get back to its home at the center of the labyrinth. The game was meant to be an updating of an epic tale, a reflection on the present, when so many are adrift, desperately needing to get back to a home of some sort. “Most of us have been disconnected physically from the University of Chicago campus, which is a kind of home,” Jagoda says. “So we wanted an allegorical narrative about helping one another come back home and about what it means to return to and rethink a home that's been transformed” (qtd. in Weise).

Fig. 1 The interface for A Labyrinth. Image courtesy of Patrick Jagoda for Fourcast Lab.

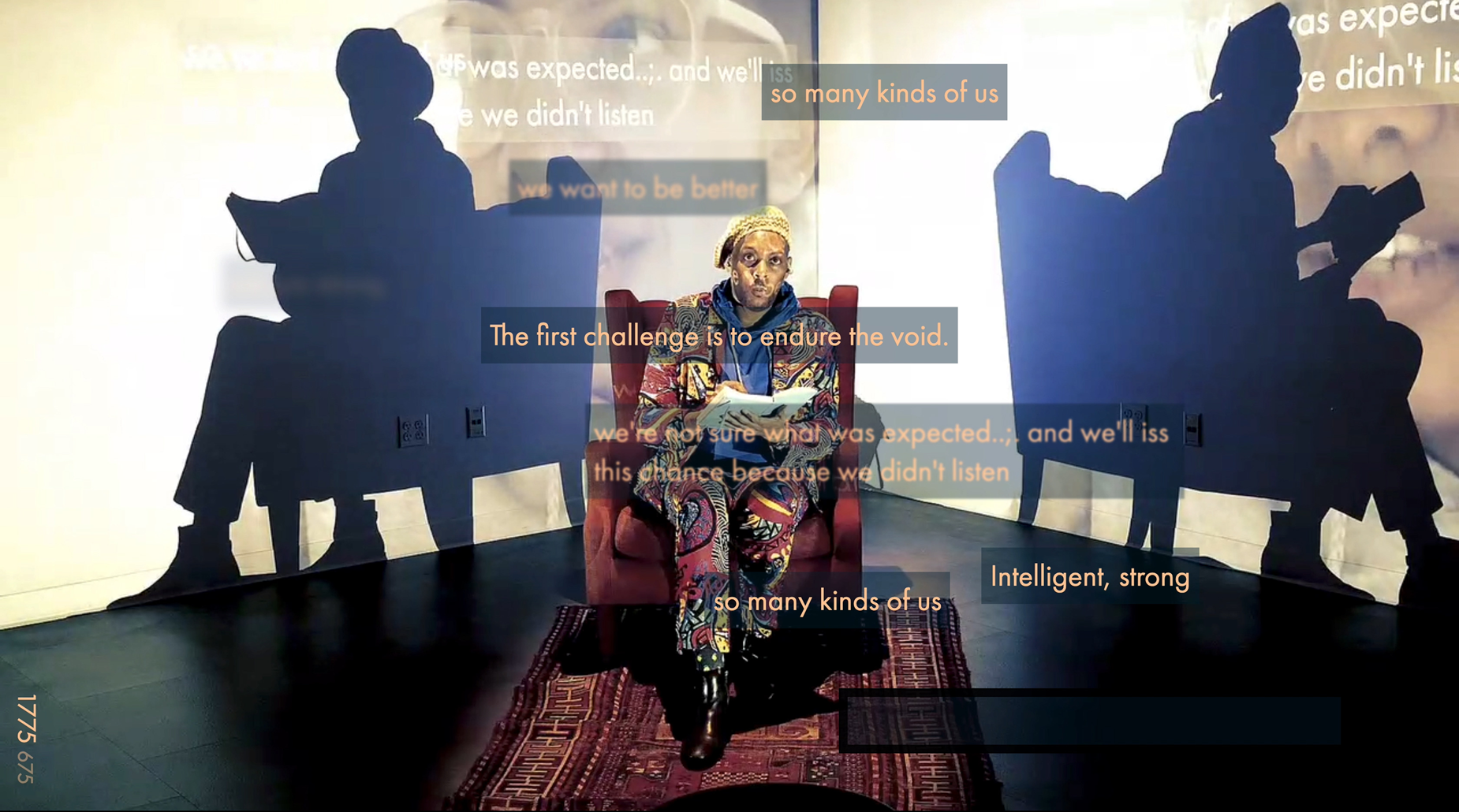

Six months into the pandemic, the Fourcast team followed up with a second ARG, ECHO, specifically addressing the mental and physical health of the players. In addition to team-based quests, a ninety-minute livestreamed finale was added, taking participants through a virtual portal in the Regenstein Library and into a series of interactive rooms that featured characters from an echo world, sonically as well as socially distanced yet palpably related to our own (fig. 2). Some of the participants took it upon themselves to tell stories about the pandemic to these kindred strangers. “It's difficult to gain critical distance when you're in the middle of a situation,” explains Jagoda. “So we tried to defamiliarize the COVID-19 pandemic by thinking back to the 1918 influenza pandemic, and then asking people to speculate about a possible future engaging with our present” (qtd. in Austen-Smith).

Fig. 2 An image from the ECHO finale, courtesy of Ben Kolak for Fourcast Lab.

A team of first-year medical students called the Pritzker Scrubs used Twine, a nonlinear storytelling tool, to create a script about COVID-19 from the perspective of the virus. “It relies a lot on logic—what decision do you make in order to infect as many people as possible?” explains Mahmoud Yousef, the captain of the team. “In the end, we see the strengths and weaknesses of the virus, which we hope teaches people how to use that to their advantage and protect themselves and their communities” (qtd. in Austen-Smith). The labor-intensive work needed to pull off this script left a muscle tone of sorts, more lasting than the game itself. “My teammates are now really close friends,” says Yousef. “We shared many memories with each other that we will keep forever” (qtd. in Austen-Smith).

Games like Terrarium, A Labyrinth, and ECHO are epic in the space and time they conjure up. They bring together participants across race, gender, and discipline, reconstituting players as an action-ready collective, coming to grips with existential threats that, though unequally distributed at the moment, are nonetheless species-wide in their ultimate implications and require flights of the imagination to address, not divisible along the lines of academic departments. But the epic scope of games can also translate into large-scale action of other sorts, taking the form not of an exuberant inventiveness uniting one particular campus but of an extended partnership distributed across several institutions, and indeed across national borders, though operating within the classroom of one particular discipline. Games such as these are global collectives in one sense but locally situated and individually embodied in the existential threat tackled in each instance. Play the Knave, a mixed-reality game developed by Gina Bloom to teach Shakespeare to K–12 students, is a case in point.

Conceived in 2013, Play the Knave is a long-running saga, the work of a continually expanding team of collaborators. It began with faculty members and students from several departments at the University of California, Davis—English, computer science, and cultural studies—interested in gamifying literary studies, particularly Shakespeare. Though initially targeting college students, the game's audience has broadened in recent years. Bloom, the project director, has been actively reaching out, combining social-justice pedagogy with game-based pedagogy in primary and secondary schools (Bloom et al.). Since Shakespeare is the only author specified on the Common Core English Language Arts Standards in the United States and on the national curriculum in the United Kingdom—and in the national curricula of many former British colonies—the stakes for innovation are especially high.

Through an internship program, two dozen UC Davis undergraduate students introduced Play the Knave to K–12 classrooms in Northern California. Just before the pandemic hit, Bloom went further, taking the game to two South African high schools: the German School in Cape Town, a private school serving mostly white students, and Thuto-Lore, a public school in the Sharpeville Township, the site of a 1960 massacre by the apartheid government, serving mostly Black students (fig. 3). She is now collaborating with three South African educators—Lauren Bates, Fazeela Haffejee, and Kelly McKenzie—to bring the game to more schools in the Western Cape, especially underserved schools that typically have over forty students per class, where Shakespeare is often greeted with trepidation or indifference.

Fig. 3 Students at Thuto-Lore, in the Sharpeville Township, South Africa, playing Play the Knave. Photo courtesy of Gina Bloom.

South Africa is a fitting choice as a project site. Over the past decades, as the postapartheid government tries to grapple with the legacy of social injustice, the country has continued to be plagued by violence. Youths of color living in townships are especially vulnerable to crimes and gang activities, although violence is a problem for South Africans across the board, irrespective of race, geographic location, or socioeconomic level. Gated communities have sprung up, relying on electric fences and private security for protection. These have done little, however, for the physical, social, and emotional well-being of youths of color. Could literature classes help by encouraging students to take things into their own hands, prompting imaginative responses to the existential threats facing them each day? The Shakespeare plays mandated by regional education departments, such as that of the Western Cape, make the school curriculum an ideal testing ground. Assigned texts usually include some of the most violent plays, Othello and Macbeth foremost among them. What might literature classes make of these plays if gamified through Play the Knave? Is there a chance students might speak in their own accents, feel with their own bodies, and act from their own histories?

Play the Knave is a highly interactive game ideal for developing countries. It does not need broadband Internet, a scarce resource in South Africa. In addition to a computer and a projector, it requires only a Kinect motion-sensing camera that maps the voices and physical movements of players onto avatars on a digital platform. (Since Microsoft stopped manufacturing Kinect cameras, there is a glut of used ones available on the cheap.) Students can either choose from the hundreds of scripts from Shakespeare's plays preloaded onto the platform or write their own scripts, using an online tool, the Mekanimator Scriptmaker, to upload them to the system. They then pick their virtual cast by choosing from a wide range of avatars to represent Shakespeare's characters (fig. 4). With these in place, students perform the scenes karaoke style, activating the digital interface in the process. As the Kinect camera follows the speech and movement of the students, the avatars on-screen speak and move in tandem. The students are in effect producing two performances simultaneously, one in the physical classroom and the other virtually on-screen. The virtual performance is recorded, yielding a short animated video that can be edited and analyzed.

Fig. 4 An avatar-selection screen from Play the Knave, courtesy of Gina Bloom.

Bloom's research thus far shows that the digital platform is especially helpful in freeing the students’ imaginations, encouraging them to choose unorthodox avatars for Shakespeare's characters, and thinking through the consequences of these casting decisions. How might this student-generated game pedagogy work in 2021, under the shadow of an ongoing pandemic?

Even though COVID-19 was fairly well under control in South Africa in its early days, a second wave has been brutal, resulting, as of 15 February 2021, in 1,492,909 infections and 48,094 deaths in a country of 58.56 million (“COVID-19 Dashboard”). Travel bans have been imposed. And yet, even with these devastations, the South African public health infrastructure remains ahead of its counterpart in the United States. While genomic sequencing is rarely performed in this country, it has been a standard practice in South Africa since the building of the KwaZulu-Natal Research Innovation and Sequencing Platform (KRISP) in 2017, enabling it to spot new mutations in viruses as soon as they occur. Genomic sequencing is relatively low-budget; developing countries can take the lead here. Hundreds of genomic samples of the COVID-19 virus have been sequenced in South Africa since the pandemic began in March 2020 (Cyranoski).

It was this painstaking work that enabled the KRISP team to identify a new variant of the coronavirus, 501Y.V2, with mutations in its spike protein that make it transmit more easily, infect a younger demographic, and possibly evade the antibodies released by some of the vaccines. The announcement was made on 18 December 2020 by Zweli Mkhize, South Africa's health minister, and Tulio De Oliveira, the director of KRISP. The data were shared with the World Health Organization and scientists around the world (“South Africa”). In a separate statement, De Oliveira noted, “Genomic sequencing is vital to understand Covid-19.” The new variant “appeared very quickly and started dominating almost all the genomes we analysed from the past two months. Ninety percent of this second wave is dominated by this single lineage” (qtd. in Craig). There has been a “shift in the clinical epidemiological picture,” Mkhize affirmed (qtd. in Cele). He added that it was the South African findings that prompted British researchers to look for similar mutations in their own genomic samples and identify the variant then circulating in the south of England, leading to a new lockdown order for many parts of the United Kingdom on 23 December (Craig).

Clearly, there is much to learn from South Africa, a former British colony now leading the way in COVID-19 research. Game pedagogy is a two-way street in this context, a conduit for knowledge reciprocity, with a learning curve on both sides. Meanwhile, South Africa does not have the luxury of pivoting to virtual learning for months on end, since most families do not have reliable access to the Internet. Schools will have to find ways to open safely. Fortunately, Play the Knave is ready for just that eventuality. Its digital platform allows the socially distanced classroom to remain intimate and expressive, with the students wearing masks and their avatars not.

The game will launch as soon as the new academic year starts up at the end of March 2021. Meanwhile Bloom has been working with a former colleague, the computer scientist Nicholas Toothman, now a professor at California State University, Bakersfield, to develop a remote-collaboration feature that allows players to create a joint performance asynchronously. One student can perform a character in a scene and record it, then another student can layer on a second character. Eventually, all the avatars would be interacting in the same video, though none of the students would have been in the same room together at the same time. Once this remote-collaboration feature is fully tested and fine-tuned, Play the Knave will become an invaluable education resource during public health crises, a user-generated game pedagogy adaptable to any number of situations limiting classroom interactions—and any number of players.

Many unknowns remain. For one thing, since the virus mutates naturally, continually eroding the efficacy of existing vaccines as it circulates and replicates around the world, the years ahead will require global collaboration to prevent fresh outbreaks. The more partnerships we build, the more resilient we will be for unforeseeable hazards that arise. Literature and catastrophe have long been intertwined. A 1500 BCE text known as the Ebers papyrus mentions a disease that “has produced a bubo” (Walker). Book 1 of the Iliad likewise refers to a “fatal plague” sent by Apollo to punish Agamemnon (Homer 77). It is not surprising that this epic threat should still be with us, upending our world, but also educating us in the process, as long as we are game.