Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 December 2020

The divided self in James’s fiction may be regarded as an inevitable structural consequence of James’s desire to dramatize the problem of the free spirit in an enslaving world. But the divided self required by art is not essentially different from the divided self known to psychology, and an understanding of the anxieties of that self, particularly of the “obsessive imagery” James uses to depict those anxieties, enriches our understanding of James’s work. The fear of a world that threatens one’s being issues in an elaborate development of an escape motif; of imagery of seizure by the eye and by the world of appearances; and of imagery of petrification, reflecting a dread of being turned into a mere tool or machine. James’s vision of “the great trap of life” permits him to come to terms with his own limitations and culminates in a searching philosophic examination of the problem of free will and determinism.

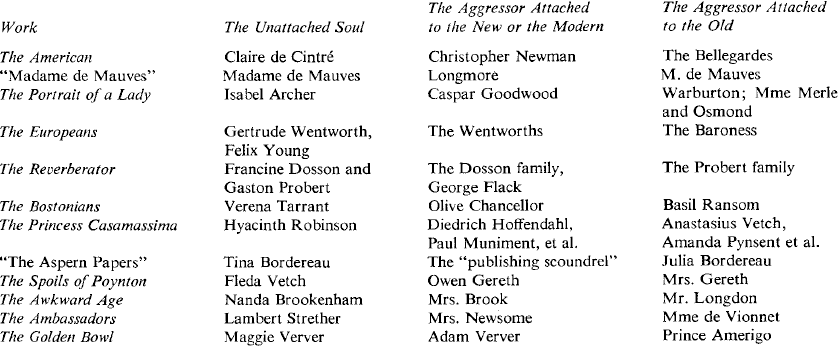

1 The following table exhibits the basic principle at work in the construction of characters in tales from 1877 to the major-phase period:

| Work | The Unattached Soul | The Aggressor Attached to the New or the Modern | The Aggressor Attached to the Old |

| The American | Claire de Cintré | Christopher Newman | The Bellegardes |

| “Madame de Mauves” | Madame de Mauves | Longmore | M. de Mauves |

| The Portrait of a Lady | Isabel Archer | Caspar Goodwood | Warburton; Mme Merle and Osmond |

| The Europeans | Gertrude Wentworth, Felix Young | The Wentworths | The Baroness |

| The Reverberator | Francine Dosson and | The Dosson family, | The Probert family |

| Gaston Probert | George Flack | ||

| The Bostonians | Verena Tarrant | Olive Chancellor | Basil Ransom |

| The Princess Casamassima | Hyacinth Robinson | Diedrich Hoffendahl, Paul Muniment, et al. | Anastasius Vetch, Amanda Pynsent et al. |

| “The Aspern Papers” | Tina Bordereau | The “publishing scoundrel” | Julia Bordereau |

| The Spoils of Poynton | Fleda Vetch | Owen Gereth | Mrs. Gereth |

| The Awkward Age | Nanda Brookenham | Mrs. Brook | Mr. Longdon |

| The Ambassadors | Lambert Strether | Mrs. Newsome | Mme de Vionnet |

| The Golden Bowl | Maggie Verver | Adam Verver | Prince Amerigo |

The list might be much extended. There are, it goes without saying, complexities in structure that the paradigm cannot begin to suggest. But the formula of enslaver-aggressor versus free (i.e., divided) spirit persists throughout.

2 The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness (Baltimore: Penguin, 1965), pp. 137, 46. All subsequent references to Laing are to this edition.

3 The Novels and Tales of Henry James, 26 vols. (New York: Scribners, 1907–17). All subsequent references to James's work are to this edition unless otherwise indicated.

4 To Edmund Gosse in 1896 James writes: “But I stay in solitude. I don't see a creature. That, too, dreadful to relate, I like” (The Letters of Henry James, ed. Percy Lubbock, New York: Scribners, 1920,1, 248). To Mrs. John L. Gardner he writes: “I return to England to enter a monastery for the rest of my days”; and again, he says he will get away from London “as quickly as possible into the country—to a cot beside a rill, the address of which no man knoweth” (i, 239).

5 F. O. Matthiessen and Kenneth B. Murdock, ed., The Notebooks of Henry James (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1947), p. 311.

6 James was particularly struck by “the interest [his father] shed for us on the whole side of the human scene usually held least interesting—the element, the appearance, of waste which plays there such a part and into which he could read under provocation so much character and colour and charm, so many implications of the fine and worthy, that … enlarged not a little our field and our categories of appreciation and perception … we breathed somehow an air in which waste, for us at least, couldn't and didn't live.” Notes of a Son and Brother (New York: Scribners, 1914), p. 111.

7 The advent of World War I prompted James to denounce “all the active great ones of the earth, active for evil, in our time (to speak only of that) from the monstrous Bismarck down!” (Letters, ii, 390).

8 “The Tyranny of the Eye: The Observer as Aggressor in Henry James's Fictions,” Diss. Yale 1969.

9 The Tragic Muse, vii, 168; Ch. ix.

10 F. O. Matthiessen, The James Family (New York: Knopf, 1947), p. 250.

11 Preface, xi, xii.

12 “The Ironic Imagery and Symbolism of James's The Ambassadors,” Criticism, 9 (Spring, 1967), 174–96.

13 “Henry James and the Trapped Spectator,” Explorations: Essays in Criticism (London: Peregrine, 1964), pp. 164–65.

14 A Small Boy and Others (London: Macmillan, 1913).

15 A Small Boy and Others, pp. 184–85.