No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

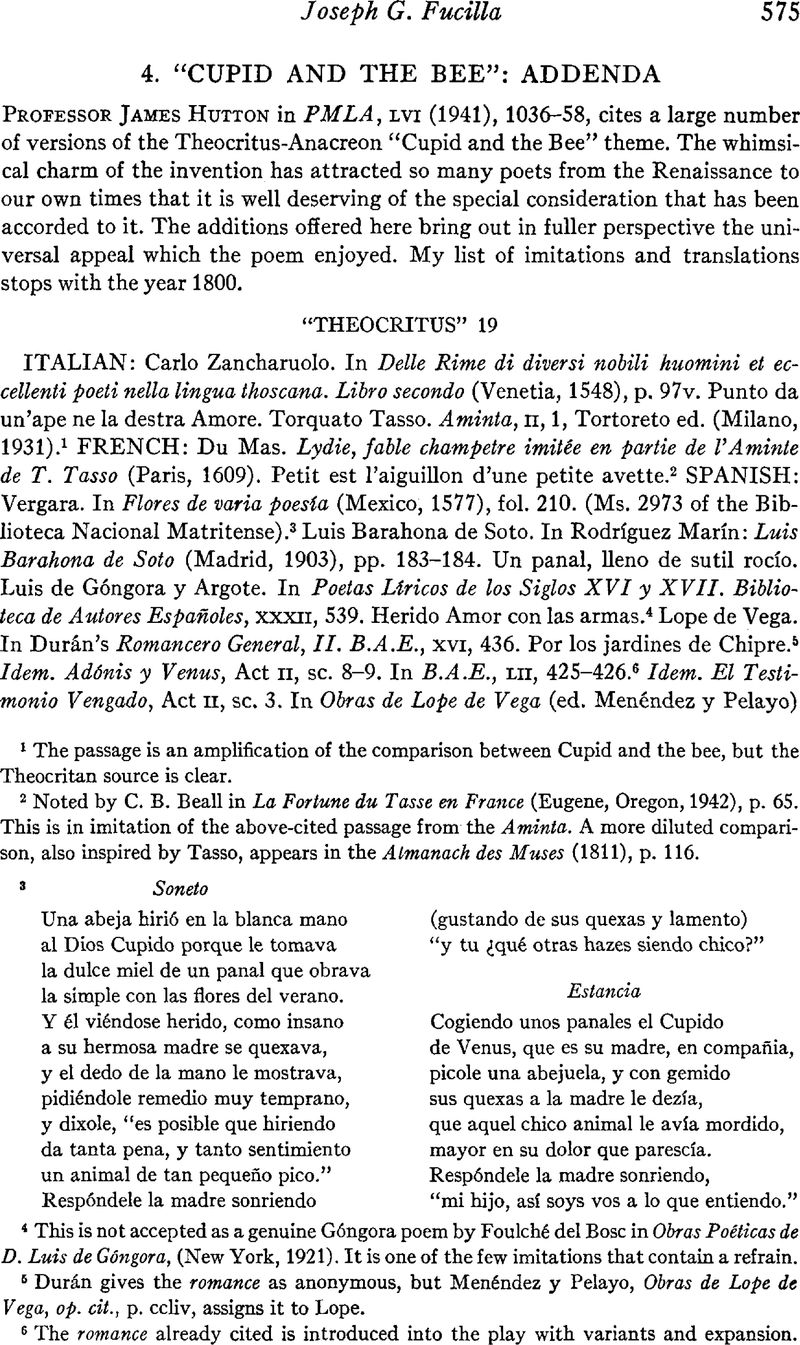

“Cupid and the Bee”: Addenda

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 December 2020

Abstract

- Type

- Comment and Criticism

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Modern Language Association of America, 1943

References

1 The passage is an amplification of the comparison between Cupid and the bee, but the Theocritan source is clear.

2 Noted by C. B. Beali in La Fortune du Tasse en France (Eugene, Oregon, 1942), p. 65. This is in imitation of the above-cited passage from the Aminta. A more diluted comparison, also inspired by Tasso, appears in the Almanack des Muses (1811), p. 116.

4 This is not accepted as a genuine Góngora poem by Foulché del Bosc in Obras Poéticas de D. Luis de Góngora, (New York, 1921). It is one of the few imitations that contain a refrain.

5 Duran gives the romance as anonymous, but Menéndez y Pelayo, Obras de Lope de Vega, op. cit., p. ccliv, assigns it to Lope.

6 The romance already cited is introduced into the play with variants and expansion.

7 The last two imitations were noted by M. A. Buchanan in “Short Stories and Anecdotes in Spanish Plays,” MLR, iv (1908–09), 180. On the period when the three plays were written, 1597–1603, 1596–1603, 1613–22 respectively, see Morley and Bruerton, Chronology of Lope de Vega's Comedias (New York, 1940), p. 362 and p. 368.

9 Meseguer was born about 1760.

10 The caption—“Cupid wounded. From Anacreon and Theocritus—” makes clear the double source of the poem.

11 The 19th Idyllium of Theocritus Attempted in the Cumberland Dialect

12 The initial line should be compared with the beginning of the American song cited by Hutton (PMLA, lvi, 1037), As Cupid in a garden stray'd.

13 Lines 7–10

are virtually copied from the poem in Town and Country Mag.

As to tie English popular song: To heal the wound (PMLA, lvi, 1044) it is more closely related to Tasso's Aminta, Act i, p. 42, op. cit. than to Guarini's madrigal.

14 Götz' poem avowedly comes from Guarini.

15 The first two imitations are noted in G. Witkowski, “Die Vorläufer der anakreontischen Dichtung in Deutschland.” Zeitschrift für vergleichende Literaturgeschichte und renaissance Literatur, Neue folge, iii (1889–90), while the last two are noticed in F. Ausfeld, Die deutsche anakreontische Dichtung des 18. Jahrhunderts … (Strassburg, 1907).

It is interesting to observe that the first painting embodying the theme is by Lucas Cranach. It is now in the Nürnberg National Museum. In the upper right hand corner are the verses of Sabinus (PMLA, lvi, 1041). William H. Riback has called my attention to an article in Time for Oct. 19, 1936, which deals with the loan exhibition of German art brought to the U. S. through the efforts of Mrs. Helen Appleton Read, art critic of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Cranach's Venus und Amor, here reproduced, is described as the “high spot of the whole exhibit.”

16 The villanella belongs to the sixteenth century.

17

This is, to be sure, only an echo of Anacreon, but it is an unmistakable one. Rolli had previously made a translation of the Greek author: Delle ode d'Anacreonte Teio (Londra, 1741).

18

19 The composition appears anonymously in Coleccion de Poesías Escogidas. A note here states that it comes from the manscript Flores de Varía Poesía (Mexico, 1577).

20 This is a re-working of the poem cited above, and is included by Rodríguez Marín in his Luis Barahona de Soto (Madrid, 1903), p. 309.

21 See Quevedo's note, op. cit., p. 455, in which he claims that all of the translators including Estienne and Elias Andreas have carelessly translated the conclusion of Anacreon's poem.

22 The first version is a translation, while the second is a sprightly adaptation minus the usual ending.

23 Faria y Sousa was a Portuguese who wrote both in his native tongue and in Spanish. A fellow countryman—Pedro de Andrade Caminha—has two unedited imitations in Portuguese: De urna abelha o Amor na mão mordido and Ferido de urna abelha Amor fogia, but I have no means of determining whether he is indebted to Anacreon or to Theocritus. See Carolina Michaelis de Vasconcelos in Revue Hispanique, viii (1901), 429 and 434.

24 The madrigal by Luis Martin in Flores de Poetas Ilustres, i (Sevilla, 1896), p. 43, is an imitation of Tasso's Mentre madonna s'appoggiò pensosa, but the detail of the bee hidden within the rose, entre una rosa una abeja escondida, comes from Anacreon.

25 This poem is also an imitation of Tasso's Mentre Madonna ….. However, the ending:

26 The opening verses have some originality:

27 Ascribed to J. W. in Poetical Register (1814), p. 334. Another poem: Once as Cupid tir'd with play, cited by Hutton (op. cit., p. 1057, also appeared in the Universal Mag., June, 1762, p. 320.

28 The prick of a rose thorn replaces the bee's sting in this poem. Both the Lessing and Gleim imitations have been noted by Ausfeld, op. cit.