No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

Richard Steele and William Lord Cowper: New Letters

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 December 2020

Abstract

- Type

- Notes, Documents, and Critical Comment

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Modern Language Association of America, 1965

References

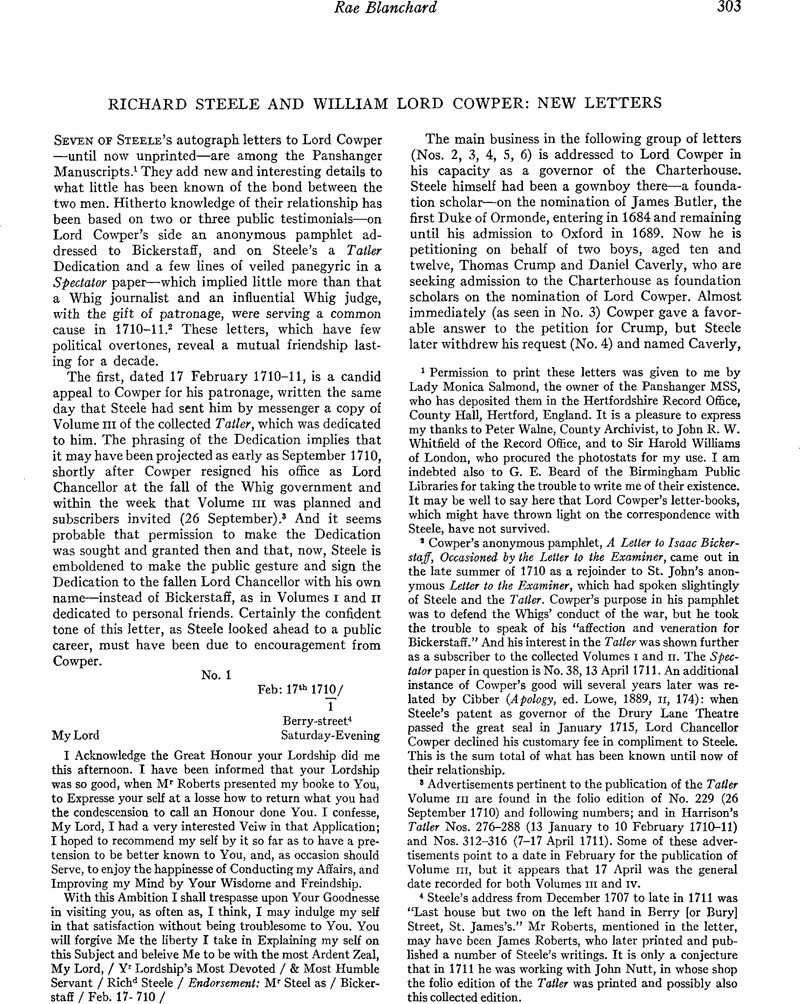

1 Permission to print these letters was given to me by Lady Monica Salmond, the owner of the Panshanger MSS, who has deposited them in the Hertfordshire Record Office, County Hall, Hertford, England. It is a pleasure to express my thanks to Peter Walne, County Archivist, to John R. W. Whitfield of the Record Office, and to Sir Harold Williams of London, who procured the photostats for my use. I am indebted also to G. E. Beard of the Birmingham Public Libraries for taking the trouble to write me of their existence. It may be well to say here that Lord Cowper's letter-books, which might have thrown light on the correspondence with Steele, have not survived.

2 Cowper's anonymous pamphlet, A Letter to Isaac Bickerstaff, Occasioned by the Letter to the Examiner, came out in the late summer of 1710 as a rejoinder to St. John's anonymous Letter to the Examiner, which had spoken slightingly of Steele and the Tatler. Cowper's purpose in his pamphlet was to defend the Whigs' conduct of the war, but he took the trouble to speak of his “affection and veneration for Bickerstaff.” And his interest in the Tatler was shown further as a subscriber to the collected Volumes i and ii. The Spectator paper in question is No. 38, 13 April 1711. An additional instance of Cowper's good will several years later was related by Cibber (Apology, ed. Lowe, 1889, ii, 174): when Steele's patent as governor of the Drury Lane Theatre passed the great seal in January 1715, Lord Chancellor Cowper declined his customary fee in compliment to Steele. This is the sum total of what has been known until now of their relationship.

3 Advertisements pertinent to the publication of the Tatler Volume iii are found in the folio edition of No. 229 (26 September 1710) and following numbers; and in Harrison's Tatler Nos. 276–288 (13 January to 10 February 1710–11) and Nos. 312–316 (7–17 April 1711). Some of these advertisements point to a date in February for the publication of Volume iii, but it appears that 17 April was the general date recorded for both Volumes iii and iv.

4 Steele's address from December 1707 to late in 1711 was “Last house but two on the left hand in Berry [or Bury] Street, St. James's.” Mr Roberts, mentioned in the letter, may have been James Roberts, who later printed and published a number of Steele's writings. It is only a conjecture that in 1711 he was working with John Nutt, in whose shop the folio edition of the Tatler was printed and possibly also this collected edition.

5 I am indebted to C. F. H. Evans, Librarian at the Charterhouse, Godalming, Surrey, for a search of the records there.

6 The reference to Cicero could not be traced. Steele may have had in mind any one of the three known letters, all generously and painstakingly recommending young men to Caesar's patronage: Trebatius, Praecilius, and Crassus, son of the triumvir.

7 Lord Cowper was living at his country house, Colegreen (later to be the site of Panshanger), which was near Hertford in the parish of Hertingfordbury.

8 The Whig nobleman John (Holies) Marquess of Clare and Duke of Newcastle-upon-Tyne died at Welbeck, Notts, on 15 July, two days after a fall from his horse while stag-hunting. His nephew and successor, Thomas Pelham, Lord Clare, afterwards Duke of Newcastle, became Steele's patron in 1715.

9 The procedure followed was nomination by means of a signed warrant by a governor or by the crown directed to Master and Register, who prepared the list of nominees to be elected by the governors in assembly. Nominations were made by the governors in rotation. The elections took place every other year or so, and admissions were restricted to a limited number.

10 Bower Marsh, Alumni Carthusiani: A Record of the Foundation Scholars of Charterhouse 1614–1872 (London, 1913), p. 74.

11 The dating of the letter is of interest. For a time in 1712 the Steele family apparently were living with Mrs. Steele's mother at her lodgings “the last door left hand, Bromley Street, Holborn.” But this is the only one extant of Steele's letters dated from Bromley Street. The signature bears out what has already been recorded, that about the beginning of 1712 Steele changed it, replacing Richd with Richard.

12 A Letter to the Right Worshipful Sir R. S. concerning his Remarks on the Pretender's Declaration (London, 1716, Printed for E. Smith) [published 28 January 1715–16], p. 6. This anonymous pamphleteer stated that “the learned Lord Chancellor could not be prevailed on to break through the Statutes of the place to gratify your Ambition.”

13 Residence on the premises was required of the Master, and he could hold no other employments. He had complete charge of the economic government of the institution and the general educational direction of the students—forty foundation scholars and a number of boarders—and oversight of the eighty old gentlemen pensioners.

14 The exact list of the electing governors is not known. But the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishop of London, and the Bishop of Ely, the Tory ex-ministers—Lord Harcourt and the Earl of Dartmouth—the Tory Duke of Buckingham, and possibly Sir Nathan Wright would be expected to cast negative votes.

15 Steele's address from March 1715 to December 1718 was St. James's Street over-against Park Place.

16 David Scurlock (1694–1768), Oxford, B.A., 1714. See The Correspondence of Steele (Oxford, 1941), pp. 184, 329–30.

17 When Lord Cowper resigned his second tenure as Lord Chancellor in 1718, he was created first Earl Cowper. He had been raised to the peerage as Baron Wingham in 1706, when he succeeded his father as a baronet.

18 A final query which cannot now be answered: Were mutual first impressions formed between Steele and the Lord High Chancellor while Steele was a suitor in the Court of Chancery? Steele's suits heard in this Court during the early period were (1) Steele versus Christopher Rich, Patentee of the Drury Lane Theatre, 1707–10, and (2) Addison versus Steele and the trustees of the Barbados estate, 1708–(?)