In his chronicle Estoire des Engleis, Geffrei Gaimer refers to ‘a large book [in which] the first strophe is notated with music’.Footnote 1 One can hardly think of a more concise and accurate definition for the page layout standardised in the thirteenth-century chansonniers, by far the most significant sources of medieval monophony written in the vernacular. However, Gaimer's description is geographically located in England and dated to the second quarter of the twelfth century, 100 years or so before the copying of the earliest extant chansonniers, which are continental sources in most cases. This article sheds light on a certain type of vernacular song that has not been seen so far as a separate genre, distinct in style and transmission from the chansonnier tradition that it precedes by some decades. In light of the analysis of the earliest traces of notated vernacular lyric, the article will discuss the relation of this genre to the later chansonnier tradition and will further suggest a hypothesis concerning the propagandistic motivations that lay behind the rise of that ‘pre-chansonnier’ tradition.

The earliest evidence of notated vernacular lyrics comes down to us in a small and ununified group of twelfth-century sources, most of English provenance (see Table 1).Footnote 2 We may look at this corpus as another testament that ‘the English were not latecomers to a game already being played elsewhere’, as Peter Lefferts put it when discussing the development of musical repertories in the Anglo-French cultural sphere.Footnote 3 The current article takes as its focus one of these traces of a ‘pre-chansonnier’ tradition: the crusader recruitment song Chevalier mult estes guariz (RS 1548a, hereafter Chevalier). Probably the earliest extant copy of an Old French lyric,Footnote 4 with or without notation, this strophic song is solely preserved in the otherwise Latin, non-musical miscellany, Erfurt, Universitätsbibliothek, Codex Amplonianus 8˚ 32 (hereafter D-Ef 8˚ 32).Footnote 5 The text of the poem itself suggests a composition date of the mid-1140s, during the recruitment for the Second Crusade, no more than three or four decades before it was copied into its sole surviving source.Footnote 6 The song appears in a section of the manuscript that seems – based on both the script and the notation – to have been copied in England during the second half of the twelfth century. We can gain a better understanding of the scribal practice that lies behind this unicum through an examination of the multiple corrections and mise-en-page decisions made by the scribe, the kind of information that is usually harder to trace in chansonniers. Before turning to analyse the song and its manuscript presentation in more detail, the first part of this article is devoted to a survey of the characteristics of some other sources of notated strophic lyrics, in order to situate Chevalier in the wider context of the contemporary copying of secular music.

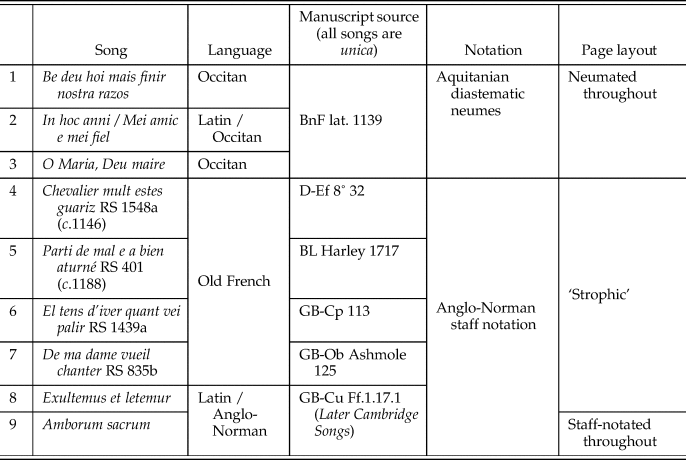

Table 1. Notated vernacular lyrics probably copied before 1200

Pre-chansonnier strophic page layouts

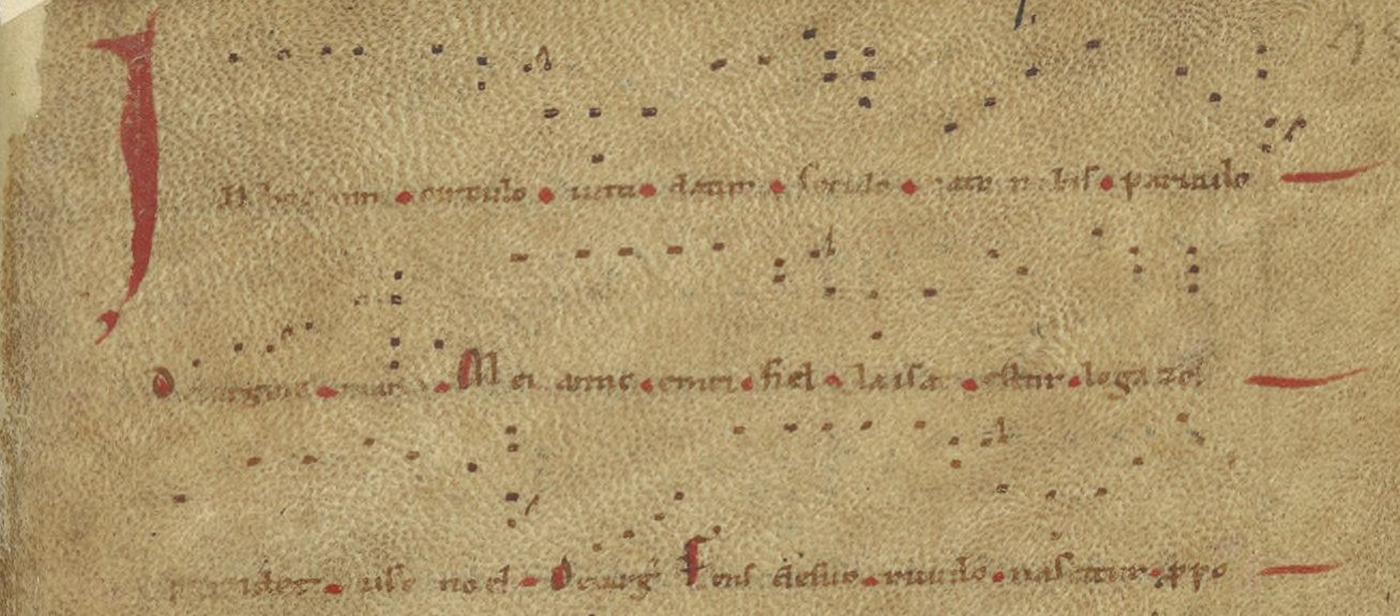

In terms of musical notation and page layout, the twelfth century was a period of significant transition, as well as a time at which different and long-standing methods coexisted.Footnote 7 Although staff-notation predominated as the century progressed, neumatic forms remained common. Both liturgical and secular manuscripts intended for neumation adopted a uniform text layout that made the addition of neumes convenient; even in those parts of a manuscript in which neumes were not added above the text, the spacing between textual lines remained similar. In both diastematic and adiastematic sources, successive strophes were in many cases fully notated, with or without variation, as can be seen in the example from BnF lat. 1139 in Figure 1, where the two strophes beginning with the texts In hoc anni and Mei amic e mei fiel receive the same music.Footnote 8

Fig. 1. BnF lat. 1139, excerpt from In hoc anni/Mei amic e mei fiel, fol. 48r.

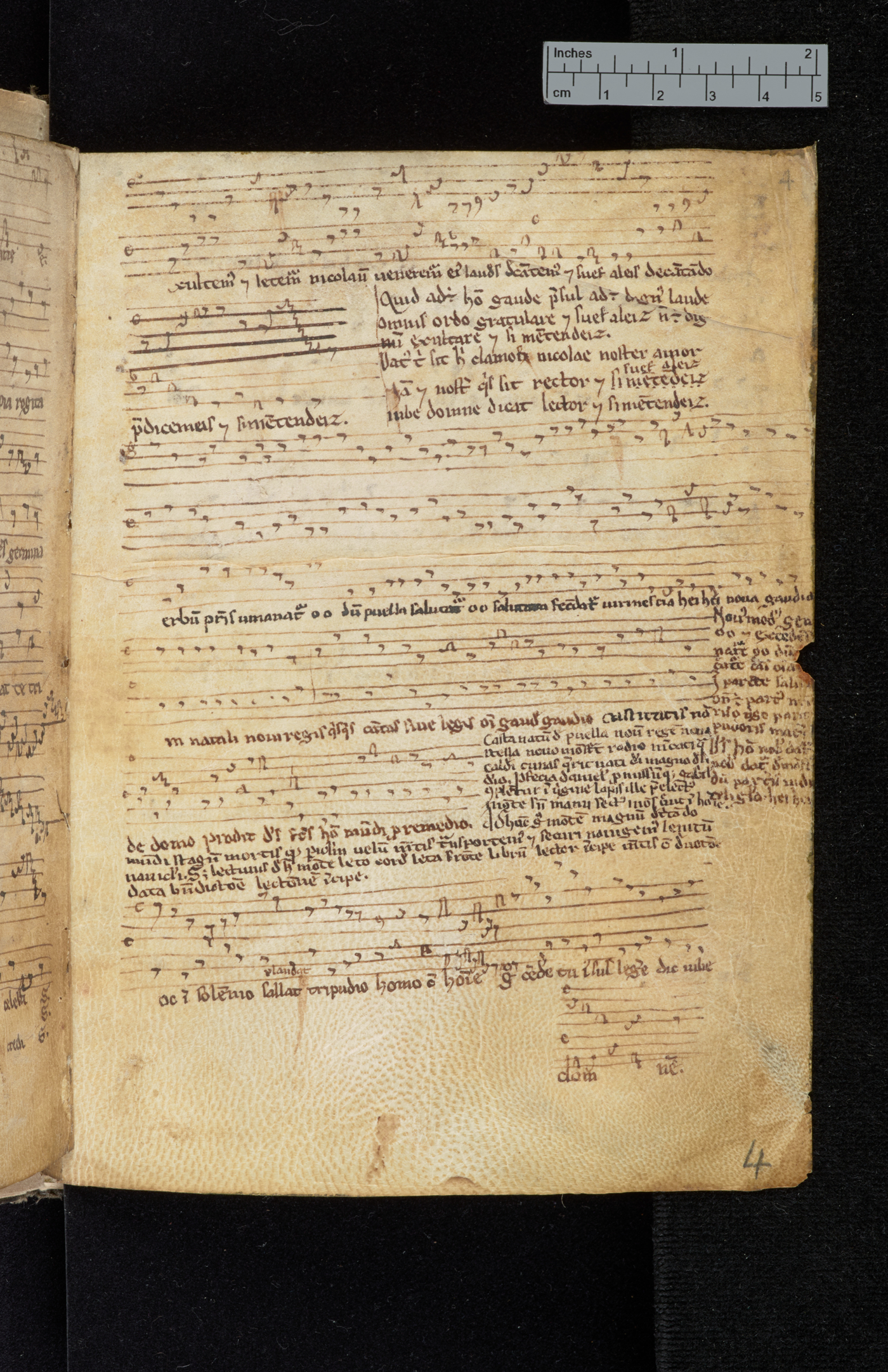

These principles of page layout are essentially different from those typical of thirteenth-century chansonniers. In the latter, only the first strophe is fully notated, while the remaining strophes are provided only with the text, consecutively copied in a separate, prose-like unit, with minimal spacing between different text-lines (I refer to this hereafter as ‘strophic page layout’). An exceptional case from the twelfth century is another book of English provenance including musical items, the so-called ‘Later Cambridge Songs’ (Cambridge University Library, Ff.1.17.1, hereafter GB-Cu Ff.1.17.1).Footnote 9 This is a Latin miscellany that includes a section with thirty-five staff-notated songs (twenty-three monophonic followed by twelve polyphonic) compressed into sixteen pages. Nineteen of these songs (fourteen monophonic, five polyphonic) are strophic and are basically similar in their page layout to the chansonniers (see Fig. 2). What is noteworthy here is that whenever a song is notated throughout, it is only because this song is not a strophic one. In other words, as in the chansonniers, in GB-Cu Ff.1.17.1 strophic songs are always notated using a strophic page layout.

Fig. 2. GB-Cu Ff.1.17(I) (Later Cambridge Songs), fol. 7r. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Unlike many of the extant chansonniers, GB-Cu Ff.1.17.1, copied on a parchment of poor quality, is anything but luxurious. According to John Stevens, the layer of the manuscript in which the songs are preserved

[was] evidently not intended to last. It contains nothing but the songs, which are untitled, unattributed … So mean an object could not conceivably have been dedicated or presented to anyone … [the copyists] were not amateurs, but fluent trained scribes. (The notation is fluid and cursive, transitional between neumatic and square.) However, on this occasion their standards were low, and a great deal of their work is freehand.Footnote 10

Stevens's account of this rare preservation of ‘informal’ song copies also reliably describes the only extant copy of Chevalier. Yet although similarly ‘informal’ and using a strophic page layout, in one aspect it is essentially different from GB-Cu Ff.1.17.1. As Helen Deeming's work on Latin as well as vernacular songs copied in England during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries demonstrates, the compilation of GB-Cu Ff.1.17.1 in the format of a small songbook is exceptional. Much of this corpus, which also includes Chevalier and constitutes the most significant ‘pre-chansonnier’ repertory, was written down on originally blank pages within (at least seemingly) unrelated books.Footnote 11 As Deeming's study reveals, such a ‘scattered’ pattern of dissemination has resulted in a general scholarly neglect of these songs. Their joint examination, however, can provide us with valuable insights into the production and consumption of lyric and music practised in different institutions in high medieval England. A glance through the Latin and vernacular songs copied in England c.1150–1250 reveals that such a manuscript appearance – coupled with the use of a strophic page layout – is not exclusive to Chevalier; while that combination is not particularly common in the Latin song repertory, it is indeed a defining characteristic of the extant vernacular lyric from England in that period.Footnote 12

Following the examination of Chevalier alongside other copies of vernacular songs dated to the twelfth century, I shall draw conclusions concerning the relation between the earlier and later patterns of song production and preservation. I examine a range of aspects, including thematic framework, dating, authorship, manuscript presentation, scribal process, musical construction and intended audiences.

A clerical chanson de croisade?

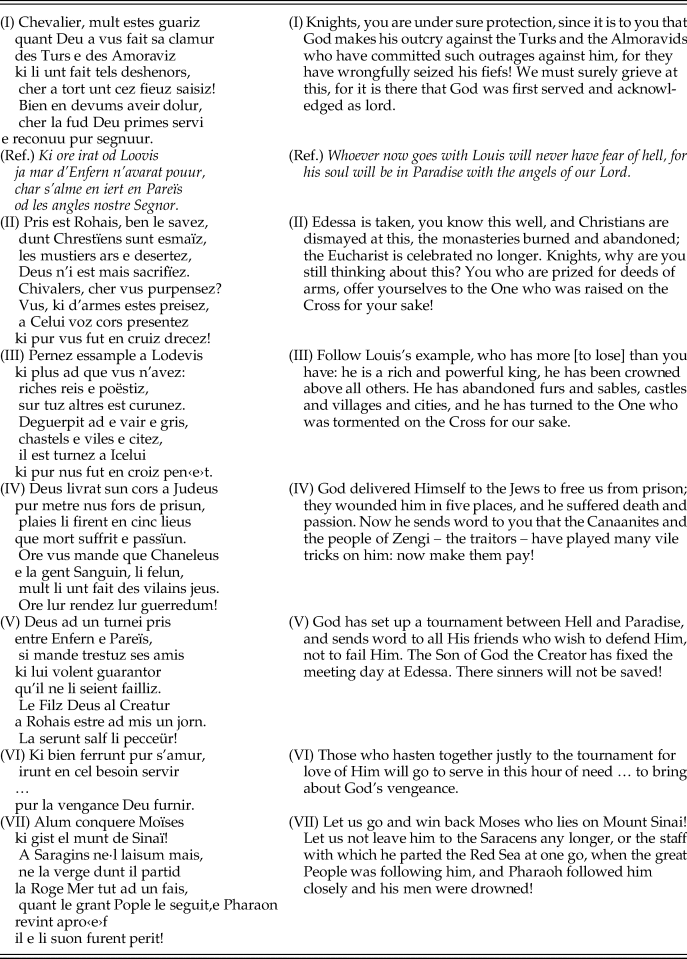

Chevalier is a hortatory crusade song, which highlights several propagandistic elements also typical of later crusade songs in the vernacular, especially those composed by the trouvères.Footnote 13 Notable among those elements is the general call for Christians, and more specifically for knights, to help God in the Holy Land; the depiction of the sin of the enemy who has ‘wrongfully seized [God's] fiefs’ in feudal and chivalric terms; and the description of the Western sorrow facing the situation at the Holy Land where ‘the Eucharist is celebrated no longer’. The complete text with English translation is as follows:Footnote 14

Alongside the exhortation to follow King Louis VII of France (1120–1180) to the Holy Land, the refrain of the song highlights an important component of crusading ideology: the promise for the crusader that his soul will ultimately be sent to paradise as a reward for his devotion and sacrifice. The song's stanzas further emphasise the value of sacrifice, and would-be crusaders are asked to ‘offer [themselves] to the One who was raised on the Cross!’ (stanza II). Louis's act of crusading is also presented in the third stanza as an act of personal sacrifice: ‘he, who has more [to lose] than you have … has abandoned furs and sables, castles and villages and cities, and he has turned to the One who was tormented on the Cross for our sake’.

Several textual elements indicate that Chevalier was composed in 1146–7, during the period of recruitment for the Second Crusade. We learn from the second stanza that ‘Rohes [Edessa] is taken … the churches are burnt and abandoned; God is no longer sacrificed there’, while the fourth stanza refers to the cruel Sanguin [Zengi] as God's enemy. The news of the fall of Edessa to the Seljuk forces led by Imad ad-Din Zengi (1087–1146) in December 1144 reached Pope Eugenius III (who reigned from 1145 to 1153) only by November 1145.Footnote 15 On 1 December Eugenius issued the papal bull Quantum praedecessores, calling for an armed pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Alongside the wider audience of Latin Christians, the bull was personally addressed to Louis VII, from whom would-be crusaders should take example according to the song. Since Louis announced his intention to take the cross by Christmas of the same year at Bourges, it is thus possible to posit a terminus post quem for the song as December 1145.Footnote 16 As for the terminus ante quem, scholars have suggested several different dates prior to the departure eastward in June 1147.Footnote 17 This date of composition situates Chevalier as contemporaneous with songs by troubadours active around the mid-twelfth century such as Cercamon, Marcabru and Jaufre Rudel, who also deployed crusader overtones in their verses;Footnote 18 moreover, the song shares some more specific vocabulary with early troubadour poetry.Footnote 19 When put against the earliest dated Old French songs preserved in the chansonniers, however, Chevalier stands alone, preceding the extant trouvère tradition by a decade or so.

The enthusiastic tone of the poem perhaps suggests that its author came from a French milieu, since it is less likely that an Englishman would have expressed such hortatory fervour in support of a French king. Yet the latter case is not impossible, since no English magnates of a comparable stature were taking part in that campaign, which might explain the reliance on Louis as a model for crusading.Footnote 20 The frequent use of knightly vocabulary, already evident in the initial second-person call addressed to the knighthood, leads most scholars to posit that the author was himself a knight.Footnote 21 The fifth and sixth stanzas, for example, present a striking knightly image: a divine tournament between heaven and hell, fought in Edessa, where ‘the sinners will be saved’. Tournaments became increasingly popular among the knightly class during the twelfth century. Since the Church was constantly attempting to legislate against such events during that period, this image can thus be associated with a secular, ‘unofficial’ point of view.Footnote 22 Another instance indicating a knightly authorship is the erroneous location of Moses's tomb in Mount Sinai in the seventh stanza, which makes a claim for a clerical background of the author less convincing.

In the face of these arguments, Anna Radaelli has suggested that there is no solid ground to reject the claim that the author had a clerical background, since the use of knightly and feudal vocabulary – including rather profane images – was among the most important characteristics of St Bernard's preaching for the Second Crusade, and even of Eugenius's Quantum praedecessores.Footnote 23 A claim for a knightly background merely on the basis of the mistaken reference to Moses's tomb thus seems too far-reaching. One can further argue that a simple cleric would have been capable of making such an error, or, alternatively, that this is not necessarily an error, since varying traditions concerning the burial-places of specific biblical figures, including Moses, spread throughout the Middle Ages.Footnote 24 Finally, it is important to stress that the distinction between clerics and laymen was not clear-cut during that period.Footnote 25 In the more specific context of vernacular lyric, Jennifer Saltzstein has demonstrated the extent to which the identities of trouvère, cleric and jongleur were intermingled in thirteenth-century Arras, the city where many of the chansonniers were produced.Footnote 26

Preceding not only the chansonnier scribal tradition but probably also the composition of the earliest extant trouvère songs, Chevalier thus might have been composed by ‘proto-trouvère’ whose poetry exhibits both clerical and lay elements, an unsurprising fusion for a song treating the theme of crusade. The song's thematic emphases, vocabulary and enthusiastic hortatory tone do associate it with later crusader recruitment songs attributed to trouvères of the high aristocracy such as Conon de Béthune (who died in 1219) and Thibaut de Champagne (1201–53), who were also prominent crusaders themselves.Footnote 27

Manuscript presentation in transition

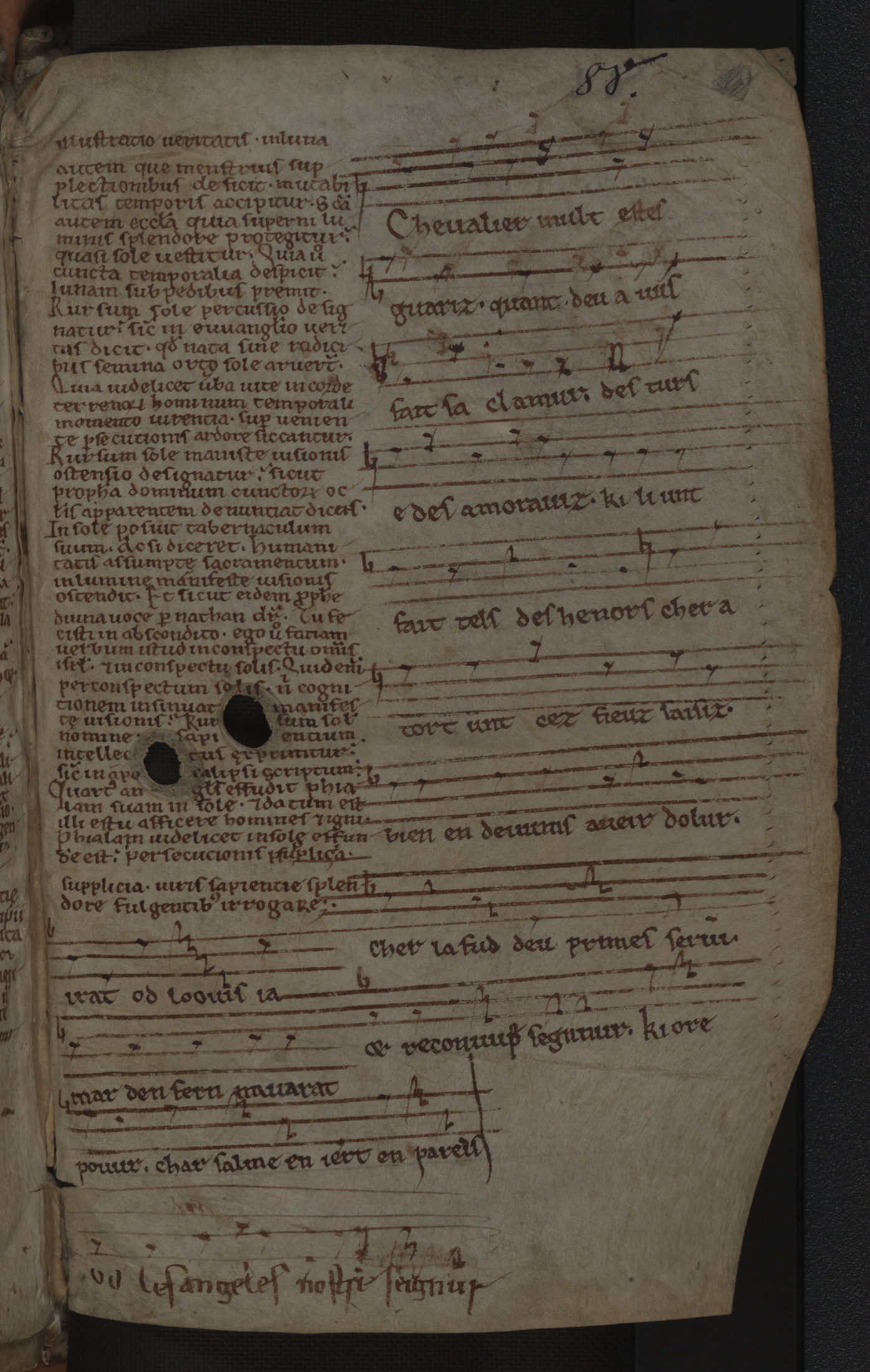

Chevalier is transmitted on both recto and verso of folio 88 in the second of D-Ef 8˚ 32's three distinct sections (see Fig. 3).Footnote 28 Located in the closing part of that section, the song appears at the end of a patristic text, an excerpt of Gregory the Great's Moralia in Iob. It is followed by another folio consisting of two short Latin texts, the sequence Axe Phoebus aureo,Footnote 29 which also includes musical notation, and Experimentum in dubiis, a short Latin text in prose. While these two Latin works are later, thirteenth-century additions in a different hand, Chevalier was probably copied during the second half the twelfth century, at the same time as Gregory the Great's text and most likely by the same scribe.

Fig. 3. D-Ef 8˚ 32, fol. 88r. Used with permission of the Universitätsbibliothek Erfurt.

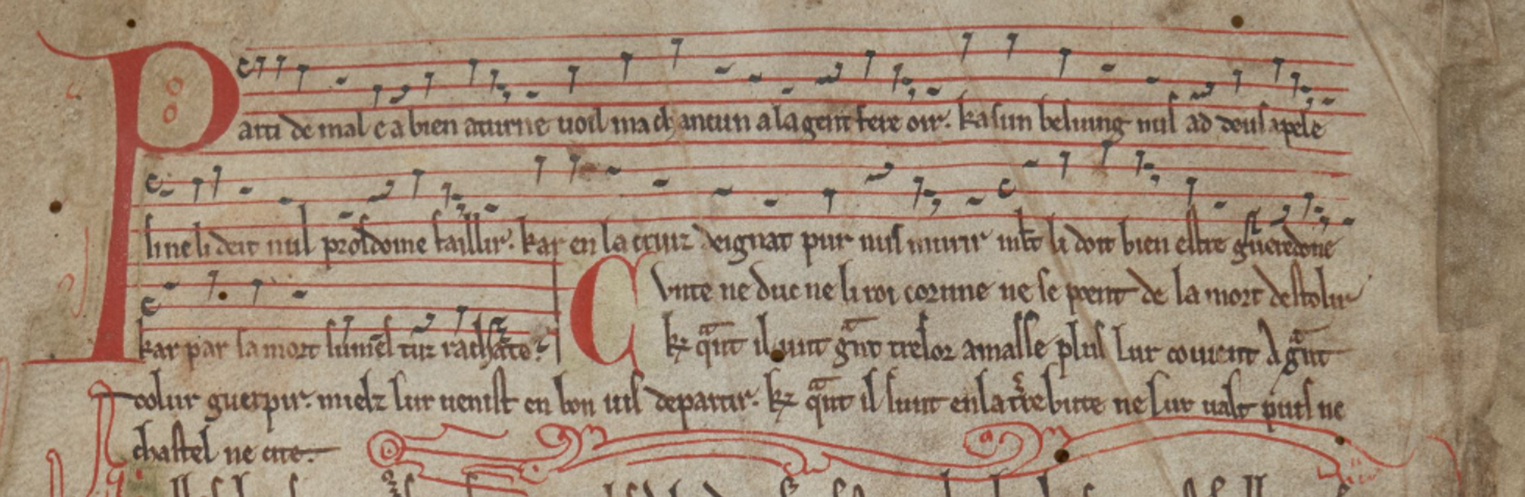

The script of Moralia in Iob and Chevalier is an informal Gothic textualis, characteristic of late twelfth- and early thirteenth-century England (c.1180–1230). It is distinctively different from the formal cursive script associated with the Plantagenet royal circle (for the latter see, for example, the script of Parti de mal in Fig. 6), as well as from the northern French Gothic script characteristic of the chansonniers.Footnote 30 Heinrich Gelzer pointed to several Poitevin palaeographic and linguistic elements, which suggests a continental origin for the scribe,Footnote 31 and Ulrich Mölk reinforced this argument while suggesting that northern French elements are present as well.Footnote 32 This song as it came down to us in D-Ef 8˚ 32 may well be understood as an ‘international’ product that includes both insular and continental elements; composed in 1146–7 in France, it was more probably copied in later twelfth-century England, perhaps by a scribe of continental origin, in a manuscript that presumably travelled to France sometime during the first half of thirteenth century, where further layers were added to it.

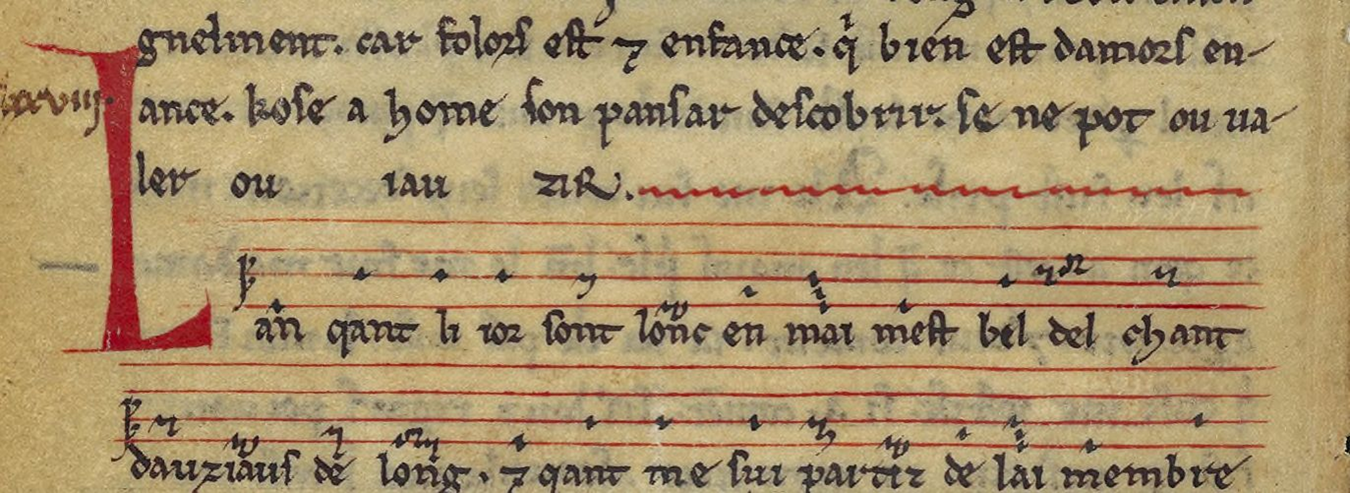

The notation of Chevalier presents another rich and complex aspect of the scribal process. It belongs to a group of late twelfth- and early thirteenth-century sources, whose notational systems are often seen as ‘transitional’ and include both neumatic and quadratic elements. The Chansonnier de Saint-Germain-des-Prés (BnF fr. 20050), probably the earliest extant chansonnier (dated c.1231),Footnote 33 is perhaps the best known among these sources. Its ‘Messine’ combination of neumatic and quadratic methods is often treated as a ‘final link’ between the earlier copying tradition and the chansonnier tradition, in which square notation became the rule.Footnote 34 The excerpt in Figure 4 from Lanquan li jorn son lonc en mai (PC 262.2) by Jaufre Rudel, a famous troubadour song perhaps composed during the preparation for the Second Crusade as well, exemplifies the kind of ‘transitional’ notation used throughout BnF fr. 20050.

Fig. 4. BnF fr. 20050, excerpt from Lanquan li jorn son lonc en mai, fol. 81v.

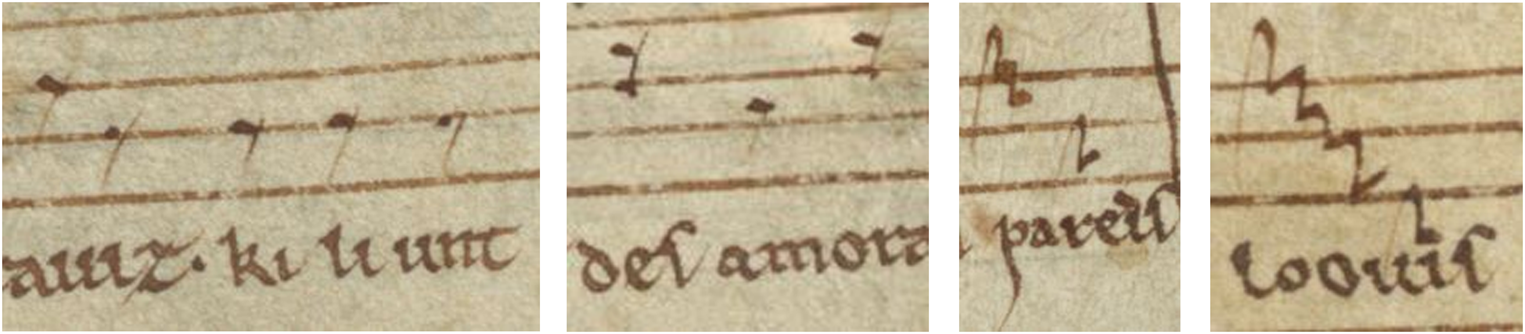

In the case of Chevalier, the notational vocabulary is fairly idiosyncratic, but it clearly belongs to the Norman-French ‘family’, which by the mid-twelfth century was among the most widespread notational systems. Among the distinctive characteristics of that notational family, to which the songs copies included in GB-Cu Ff.1.17.1 also belong, are the use of flat and natural accidentals themselves as signs of clef, as well as the clear preference for virgae over puncta. One may draw a parallel between this characterisation of the song's notation and the aforementioned versatility of its script; both aspects of manuscript presentation can be understood as ‘transitional’.Footnote 35

Let us now have a closer look at the basic note-shapes of Chevalier (Fig. 5). The shape of the virga (see the five successive virgae in Fig. 5a), by far the most common sign, is characteristic of the Norman-French notational system. Its head is slightly sloping down to the right towards a thin, rather straight right-hand tail, which is inclined to the left. The shape of the pes (see Fig. 5b, in which one can see two pedes with one virga separating between them) is more unusual, and seems to be based on the virga's shape: a lower note-head is added towards bottom-end of the tail, and the tail itself is slightly curvier and begins a bit higher in relation to the upper note-head. To the virga and the pes, one should add descending neumes, all of which begin with a thin left-hand tail followed by a snake-like descending figure, also characteristic of the Norman-French notational system and similar of their equivalents in GB-Cu Ff.1.17.1 (see Fig. 5c and for a climacus followed by a clivis and Fig. 5d for a five-notes descending neume followed by another clivis).Footnote 36 While clearly associated with a deep-rooted notational tradition, the appearance of these shapes in the manuscript is not uniform at all. Furthermore, the staves upon which these note-shapes were drawn vary in their number of staff-lines (two to four) according to the range of the melodic segment that appears at any given staff, but this element is not a coherent one either. The reason for the latter practice was probably first and foremost to save space and ink, and perhaps also time for the scribe.Footnote 37

Fig. 5. Basic note shapes in Chevalier mult estes guaritz (D-Ef 8˚ 32, fol. 88r): a) virgae; b) pes-virga-pes; c) climacus followed by clivis; and d) descending five-note neume followed by clivis.

Folio 88r, on which the musical setting of the first strophe appears, was laid out in two columns, and about two-thirds of the left-hand column is dedicated to the end of Gregory the Great's commentary on Job. Chevalier begins at the facing upper part of the right-hand column, which was never pricked. The ruling of staves is far from perfect, while the staves of the refrain that follows, which appear at the bottom of the left-hand column, are continuations of the staff-lines of the right-hand column. What might look like a notation of two coexisting melodic lines in the three initial staves is most likely a correction of a scribal error: the ‘lower’ melody is bolder and was probably added later. It is also probable that the original intention of the scribe was to supply a full melodic version of the first strophe and the refrain in the right-hand column. However, at a certain point the scribe realised there was not enough space, and then decided to expand to the space left at the bottom of the left-hand column, following Gregory the Great's text. The result is inelegant, but not difficult to decipher.

The text of the rest of the strophes was copied in the facing folio, 88v, using a different page layout in which the text is given in a single-column, prose-like format. Only the single word ‘Ki’ signals each reiteration of the refrain, while slightly larger initials indicate that a new strophe has begun. Curiously, the page does not open with the first verse of the second stanza, as would be expected, but rather with the final verse of the refrain (od les angeles nostre seignur). This must be a copying error: the scribe has mistakenly considered this verse as part of the second stanza. This is confirmed on the recto page: it is clear that this verse was missing from the original copy, and as a consequence was first left un-notated. A notated version of this verse was added later by a different hand, drawn imprecisely at the lower margin of the left-hand column. While there is no way of knowing where and when this staff was added, it is reasonable that this completion of the melody was added by someone who knew the song beforehand and valued it enough to return to it and add this bit of missing information.

Against the differences between Chevalier's copy and the earliest chansonniers in matters of work-plan and dissemination are the similarity of strophic page layout and the general association between ‘transitional’ notational systems. In both Chevalier and the chansonniers, it is hard to determine what were the intended uses of the extant song copies, which could have served a range of purposes beyond simply performance, including pre-performance preparation or instruction, preservation of materials that might otherwise be forgotten, glancing at the manuscript while the songs are being performed by others, sotto voce singing, or experiencing them visually, in the inner ear, rather than realising them as audible songs.Footnote 38 Unlike in the chansonniers, in the cases of Chevalier and other songs appearing within otherwise non-musical miscellanies of English origin, one may add the option of a commentary on other, textual items appearing within the same manuscript; as Deeming demonstrates, in many cases both these textual items (often patristic or moral) and the songs might be understood as aimed at different sorts of religious instruction.Footnote 39 In the final part this article, I point to the possibility of another, more general purpose of Chevalier's composition and copying, which concerns contemporary propaganda. Before that, I complement its thematic and musico-palaeographic examination with the analysis of formal and musical aspects of the song.

A glance into a ‘pre-courtly’ formal tradition

Another facet of Chevalier has to do with its stylistic affinity with the main types of songs preserved in the chansonniers, or with the possibility of it serving as a model, in terms of melodic and poetic structure, for other songs of a similar genre that are preserved in the chansonniers. An examination of the poetic and musical characteristics of Chevalier and a handful of other pre-chansonnier songs of English provenance against the background of the much wider repertory documented in the chansonniers will help determine whether they could have hypothetically found their way into chansonniers that do not survive. As the following analysis reveals, the answer is more probably negative, indicating that these songs belong to a distinct type with which we have no firm reason to posit that the poet-composers whose songs are documented in the chansonniers were familiar.

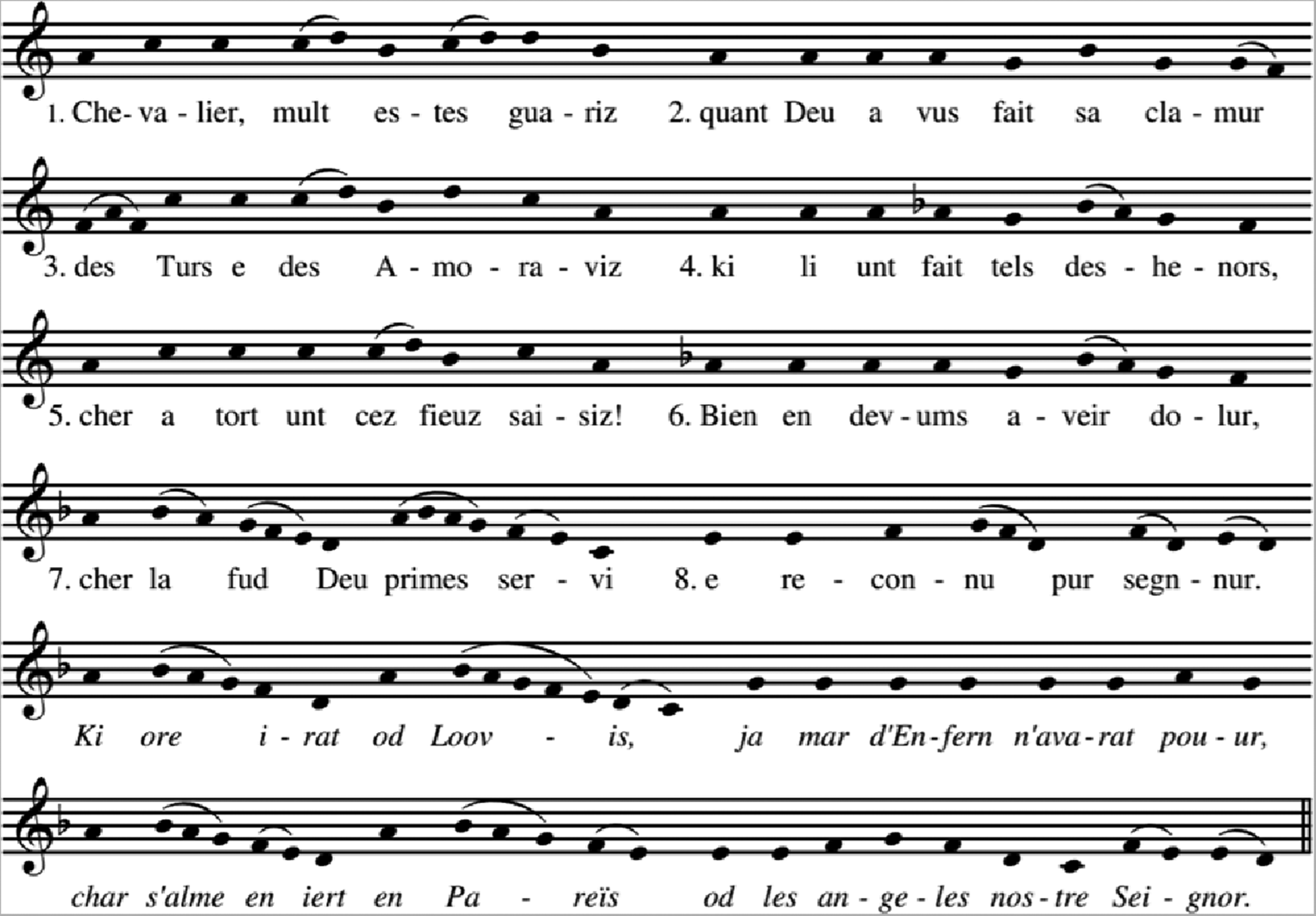

The poem of Chevalier is composed of stanzas of eight octosyllabic verses, as can be seen in the opening stanza:

Each of the seven stanzas, all with the rhyme scheme of ABABABAB, is followed by a four-verse refrain, which preserves the same principle of rhyme alternation (CDCD):

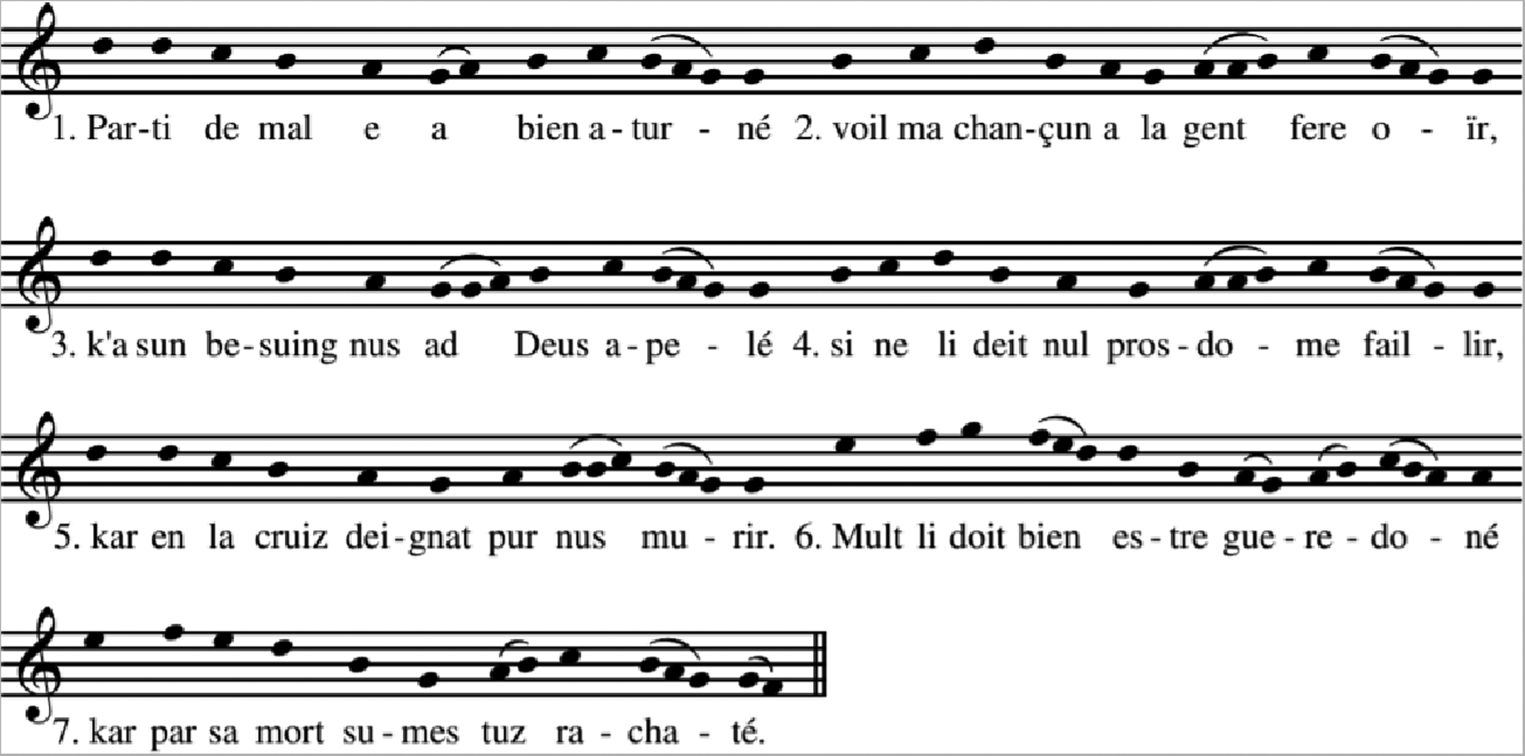

The melody supports the principle of verse alternation, with an ABA′B′A″B′CD form (see Ex. 1). The A melody (phrases 1, 3 and 5) ascend to c and d, at the top of the register, and mostly revolve around these two pitches. The B melody (phrases 2, 4 and 6), on the other hand, revolves around a, finally cadencing on F, which seems to be the central tone in these first six phrases. The melodies of the seventh and eighth phrases, which close the stanza, are more ornamented, exploring the lower register and cadencing on D; the refrain is largely based on similar melodic material and closes with an establishment of D as a central tone. The melody thus emphasises the two main structural divisions of the poem: into pairs of verses; and into stanzas and refrain-reiterations, with the two ending phrases of the stanza playing a transitional role.Footnote 40

Ex. 1. Chevalier mult estes guariz (RS 1548a), stanza I.

Poetic structures that highlight the principle of rhyme alternation in octosyllabic verses are indeed common in the troubadour and trouvère repertories. Their musical equivalents, which include more than two initial pedes (namely, when the inner-stanzaic form opens with an ABABAB structure, instead of the ABAB standardised in the pedes cum cauda form, both types of opening section that are followed by a new melodic material at the beginning of the cauda), are, however, much harder to trace in the grands chants of the chansonniers.Footnote 41 That form of Chevalier's melody, with its refrain and ‘conspicuous short-range repetitions and effects to create an instant “tunefulness”’, can be understood as falling under Christopher Page's definition of ‘lower style’ lyrics, standing in contrast to the ‘high style’ courtly song.Footnote 42 The three melodic pedes (ABABAB) that open Chevalier are followed by another musical form based on a similar principle of alternation (the CD material that closes the stanza, immediately followed by CECD in the refrain), marking the musical form of this song as exceptionally repetitive in comparison with grands chants. The overall repetitiveness as well as the principle of consistent poetic and musical verse alternation might have been experienced as a simpler and more direct expression, perhaps also adequate with the straightforward propagandistic content of the text. As the following analyses of two further ‘pre-chansonnier’ songs of English provenance reveal, we may speculate that the musical structure of this song is only a vestige of a more widespread formal tradition, in which both the repetitive quality and the equivalence between poetic and musical forms were more significant when compared with the repertory documented in the chansonniers.Footnote 43

Musical repetitiveness is also a foremost characteristic of Parti de mal e a bien aturné (RS 401, hereafter Parti de mal), another crusader recruitment song, dated to the time of preparation for the Third Crusade, and which is also solely found in a twelfth-century, otherwise non-musical miscellany of English provenance.Footnote 44 Here is the fifth stanza of Parti de mal, representative of the crusader spirit of this song, and which like Chevalier promise a godly reward for the crusader:Footnote 45

Other than its thematic emphasis and repetitive construction of musical form, this unicum shares some additional traits of preservation with Chevalier: as can be seen in the manuscript presentation of the first (notated) and second stanzas of the song in Figure 6, it is characterised by a ‘transitional’ Norman-French notational system, and it has a strophic page layout.

Fig. 6. BL Harley 1717, stanzas I (notated) and II from Parti de mal, fol. 251v.

At first glance, it seems that the melody of Parti de mal is built in a rather conventional pedes cum cauda musical structure (ABABCDE), which supports the association of this song with the grand chant formal tradition (see Ex. 2). Further examination reveals another, coexisting, formal tendency, which to my ear sounds no less prominent. The main difference between the melodies of the A and B phrases is merely the three initial pitches, while the rest of the melodies of phrases 1–5, as well as most of the seventh phrase, are largely identical throughout. That provides the melody with a characterisation of a ‘narrative’ tune, repeating for (almost) all phrases within the stanza.Footnote 46 Stevens suggests that the melody of Parti de mal may be modelled on ‘simpler songs’, such as crusader lyrics more popular in character or narrative songs set to a repetitive formula.Footnote 47 As in the case of Chevalier, that repetitive musical construction distinguishes Parti de mal from the grand chant melodies documented in high medieval chansonniers.

Ex. 2. Parti de mal e a bien aturné (RS 401), stanza I.

A similar repetitive tendency (with an ABABABC… form) and a coordination between poetic and musical forms are also found in the strophic chanson d'amour El tens d'iver quant vei palir (hereafter El tens d'iver), a third ‘pre-chansonnier’ vernacular lyric of English provenance.Footnote 48 As three of the four extant ‘pre-chansonnier’ songs copied in the second half of the twelfth century bear that unusual characteristic, almost entirely absent in the chansonniers, it is thus my inclination to consider them to be traces of a distinct type of formal construction, perhaps earlier than and different from the grand chant.

Intended audience and function

We have seen that Chevalier and Parti de mal are not only ‘pre-chansonnier’ copies of vernacular songs but that they perhaps also belong to a certain ‘pre-courtly’ type of song. Their shared thematic focus on crusader propaganda raises a question concerning the relationship between the earliest documentation of notated vernacular lyrics and the theme of crusading. In order to explore this relationship, I have examined other extant vernacular songs probably copied during the twelfth century (listed previously in Table 1), and which are mainly found in two different songbooks already discussed: BnF lat. 1139 and GB-Cu Ff.1.17.1.

These song copies are diversely linked to the theme of crusading. Folios 48r–50v of BnF lat. 1139 (probably copied 1100–1120) are devoted to three successive songs that are often thought to be a small unified group,Footnote 49 starting with the macaronic Latin/Occitan song In hoc anni/Mei amic e mei fiel (see Fig. 1). This Christmas song is followed by O Maria, Deu maire, an Occitan paraphrase (textual as well as musical) on the Marian hymn Ave maris stella, highlighting the place of Maria as the patron saint of seafarers, a theme which was obviously familiar to pilgrims and crusaders.Footnote 50 The Latin versus Ierusalem mirabilis that follows paraphrases the same hymn melody, and is the only surviving crusader recruitment song with a probable composition date of the time of the First Crusade (1096–99).Footnote 51

In GB-Cu Ff.1.17.1 there are two further macaronic songs that include both Latin and vernacular verses. The first of these, the strophic polyphonic song Exultemus et letemur (fol. 7r), is the first full song appearing in Figure 2. The second, which is the troped Benedicamus Domino setting Amborum sacrum (fols. 7v–8r), quotes from two Latin hymns: Vexilla regis and Urbs beata Iherusalem. Both hymns were very often celebrated in crusader rites during that period, and they actually reached the status of ‘crusader anthems’, the former for its belligerent take on the cross's place in Christian theology and the latter for its focus on the desirable spiritual reconquest of Jerusalem.Footnote 52 It is their inclusion together in the same Benedicamus Domino setting that strongly suggests a clerical response to the theme of crusading.

It appears that the theme of crusading was familiar within the worlds of those at whom these two very different song collections were aimed. Although it is not always the most prominent theme in any given song mentioned here, one might even say that crusading is more prevalent a theme in the small corpus of twelfth-century vernacular lyrics than the theme of love for a woman, probably the most widely recognised characteristic of medieval vernacular poetry. A related tendency is found in early vernacular epics, copied as early as the twelfth century: the heroes of both the Chanson de Roland and Chanson de Guillaume, to give the best-known examples, were understood in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries as proto-crusaders who fought against the Saracens;Footnote 53 and in the Chanson d'Antioche and Les chétifs the deeds of the early crusaders are the main theme.Footnote 54

It is reasonable to posit that the composition of vernacular lyrics such as Chevalier and Parti de mal was aimed at lay audiences, possibly of the knightly class, upon whom sung poetry in Latin might have had a lesser effect. In turn, these songs were written down, demonstrating a certain interest in the cultural world of crusading, with its associations with the knightly class. Given that all these song copies were included in Latin miscellanies or songbooks, we may assume that their intended readers/singers understood Latin at least to some extent, and even that it is more likely that they were clerics.Footnote 55 The inclusion of vernacular items in these books must have had some significance to their intended audiences. I suggest that the promotion of the crusader enterprise, a major endeavour shared by the Latin world as a whole during that period, was among the catalysts in the rise of the motivation to document vernacular lyrics. As Gerhoh of Reichersberg asserted in the mid-twelfth century, ‘the praise of God is also spreading in the mouth of laymen who fight for Christ … the whole earth rejoices in the praises of Christ, in songs in the vernacular as well’.Footnote 56 Gerhoh's ‘mouth of laymen’ is testament to the same urge to spread the crusader zeal through the medium of vernacular song, an urge that seems to have been at least partial motivation for the copying of these songs. While the medium of communication of ‘scattered’ song copies discussed in this article was particularly apt for religious instruction and pastoral care in the high medieval England,Footnote 57 Chevalier and Parti de mal demonstrate how it could have also been exploited for propagandistic aims with some important lay aspects.

In addition to being written in a Romance language and often sharing a crusader orientation, a significant portion of the extant corpus of ‘pre-chansonnier’ vernacular lyrics is preserved in ‘informal’ song copies of low material quality. Such copies, time- and space-saving and easily readable, may have served as vehicles in a larger dissemination endeavour such as the one described in the previous paragraph. A reasonable answer to the question of why only a handful of copies of twelfth-century songs of this kind were preserved is simply that although occasionally written down, such ‘practical’ copies were not intended to last for long, more often being written down in forms such as single leaves and rolls of parchment, booklets and libelli.Footnote 58 The inclusion of Chevalier at the end of Moralia in Iob in D-Ef 8˚ 32 may suggest otherwise, however. The song was perhaps copied from an exemplar that was ‘purely practical’, but its D-Ef 8˚ 32 copy was probably intended to be preserved for posterity. Similarly, all the extant song copies included in this small ‘pre-chansonnier’ repertory of English provenance are available to us only because at a certain point somebody decided that they were worth keeping and inserted them into manuscripts.

The preservation of Chevalier in D-Ef 8˚ 32 surely belongs to the wider phenomenon of the rise of written vernacular monophony during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. As a case study, it attests to several links between the early written tradition for the vernacular lyric in England on the one hand, and the continental chansonnier culture on the other. Other than anticipating the strophic page layout typical of the chansonniers by some decades, Chevalier was composed and copied at a time when early vernacular lyrics to be preserved in the chansonniers – several of which share vocabulary with this crusade song – were already being composed on the continent. Moreover, the crusader theme of Chevalier, as well as its more specific crusading vocabulary, can be found in later northern French songs by the trouvères. At the same time, this song may offer us a glimpse into an earlier pattern of vernacular song production; like several other copies of early vernacular songs coming down to us in manuscripts of British origin, the musical construction of Chevalier is characterised by a higher degree of repetitiveness when compared with the melodies typical of the later grand chant of the chansonniers. That characterisation, as well as some differences in the field of manuscript appearance, enhance the idea that this song belongs to a distinct type, which is rarely preserved in the extant chansonniers, and which might have taken an active role in contemporary propaganda – in this case recruitment for a crusade.