Published online by Cambridge University Press: 30 January 2009

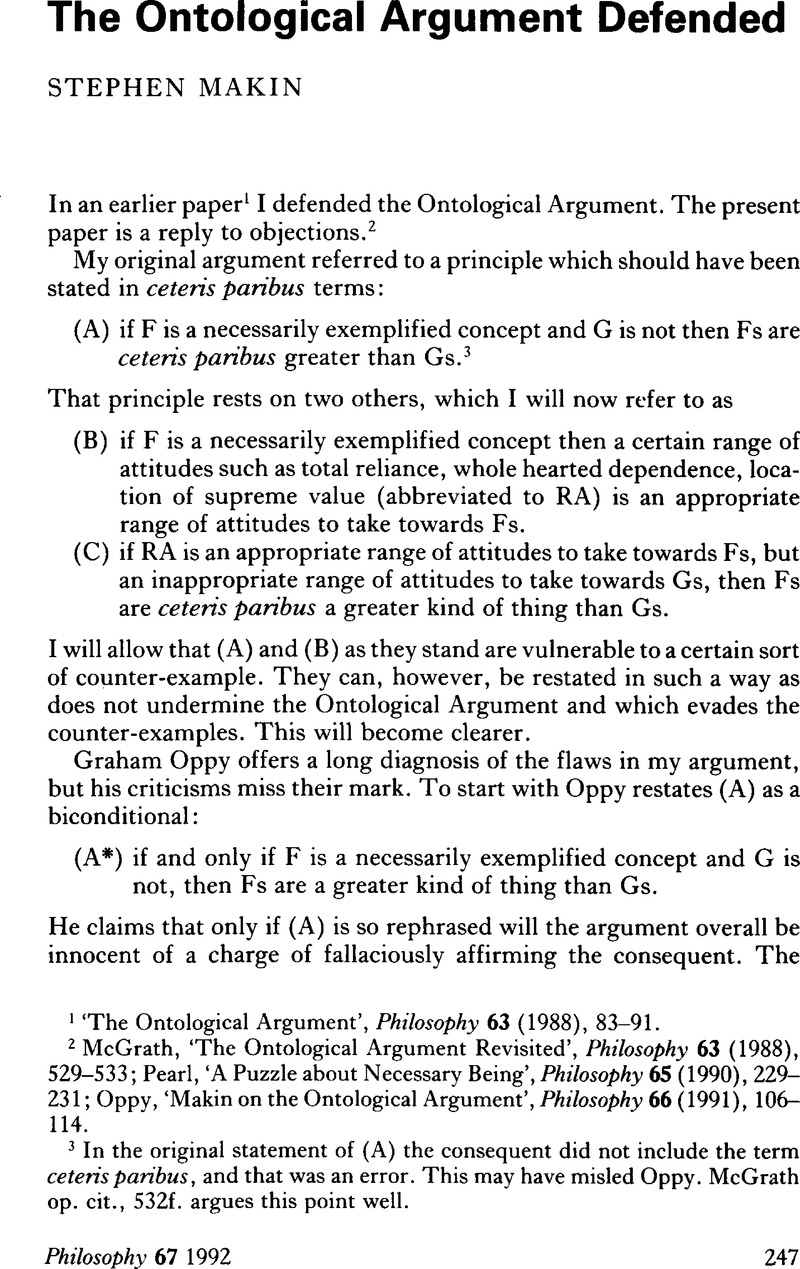

1 ‘The Ontological Argument’, Philosophy 63 (1988), 83–91.Google Scholar

2 McGrath, , ‘The Ontological Argument Revisited’, Philosophy 63 (1988), 529–533CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Pearl, , ‘A Puzzle about Necessary Being’, Philosophy 65 (1990), 229–231CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Oppy, , ‘Makin on the Ontological Argument’, Philosophy 66 (1991), 106–114.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

3 In the original statement of (A) the consequent did not include the term ceteris paribus, and that was an error. This may have misled Oppy. McGrath, op. cit., 532f. argues this point well.Google Scholar

4 Oppy, , op. cit., 112.Google Scholar

5 It is not uncommon for statements that the Ontological Argument will not work to pass as objections to it. Compare McGrath, op. cit., 531Google Scholar: ‘…there appear to be good grounds for thinking that the notion of a necessarily exemplified concept does not make sense. If it did, then one could deduce the existence of something from the mere conception of it, and this seems imposs ible’. But if the Ontological Argument were defensible, then it would not be impossible.

6 I owe notice of this sort of example to Nicholas Denyer, who pointed it out to me some time ago.

7 McGrath, Hence, op. cit., 529Google Scholar says that the concept of the greatest prime number does not make sense, since Euclid has shown that there can be no greatest prime number.