1. Introduction

Philosophers of social science generally agree that individualism is not one but many different theses. They have also come to terms with the fact that these theses do not support each other in a straightforward manner, and some of them are probably untenable. Among the various forms of individualism, in fact, only ontological individualism (OI) seems to be in relatively good shape. Or at least, it is the only individualistic thesis that philosophers have, until recently, found no compelling reason to reject.Footnote 1

According to a suitably vague formulation (we will return to this vagueness later), OI asserts that social objects, properties, or social facts more generally are constituted by individual objects, properties, or facts. The main reason why it is in relatively good shape is probably that OI is nowadays considered harmless: practically no one believes that OI can be used to defend methodological individualism (MI), as some philosophers had once hoped.Footnote 2 And yet, some work in social metaphysics has recently put OI under pressure. Brian Epstein (Reference Epstein2009, Reference Epstein2015), in particular, has challenged OI by means of counterexamples that purportedly show the dependence of (many) social facts on material facts—that is, facts that are not even about humans, let alone individuals. Following Elder-Vass (Reference Elder-Vass2017) and Haslanger (Reference Haslanger2020), I will call it the “materialist” challenge to OI. If the counterexamples are genuine, then OI will have to join MI in the cemetery of superseded philosophical theories.

In this article, I will focus mainly on The Ant Trap (Epstein Reference Epstein2015), where the case for materialism is argued in detail. Granting Epstein his preferred definition of individualism, I will show that the success of materialism depends on the endorsement of a generous conception of social properties and social facts. Against such a conception, I will argue that individualists are committed only to the claim that a particular subset of social properties is individualistically realized—namely, those properties that occur in scientific explanations. And materialists so far have failed to undermine this claim.

A couple of preliminary remarks are due before we start. First of all, this article has a modest goal. I will not try to demonstrate that OI holds; I will merely argue that refuting OI is more complicated than materialists think. Second, my argument is not historical or exegetical: it does not merely point out that materialists misrepresent OI and does not advocate that we return to some mythical primogenial version of individualism. Rather, it suggests that the materialist challenge has been made possible by a shift in the debate—away from the philosophy of science and toward the metaphysics of ordinary objects. Discussions of generic facts and properties have moved to the center of the stage, a significant drift that has changed the nature of the discussion.

I will try to show that the materialist challenge is defused if one pays attention to social science, taking a broadly naturalistic approach to metaphysics. Section 2 introduces the standard arguments in favor of OI, based on supervenience and multiple realization. Section 3 illustrates the materialist challenge. In section 4, I ask whether materialism is just a form of “extended individualism.” Sections 5 and 6 constitute the bulk of the article, where I show that materialism relies crucially on an inflated notion of “social fact” or “social property.” In section 7, I discuss some possible examples of materialistic social science. Section 8 concludes with a few remarks on the state of social ontology and its relation with current and future social science.

2. Individualism, supervenience, and multiple realization

If there is a “received view” in the contemporary philosophy of social science, surely it must be this: OI does not imply MI because social reality supervenes on individual reality without being fully reducible to it (or equivalently, the social is multiply realized at the individual level).Footnote 3 The notions of supervenience and multiple realization capture some powerful intuitions that most individualists share: first, there is no society without individuals; second, if you fix all the individual facts, you also fix all the social facts. At the same time, supervenience emancipates individualism from reductionism: because there is no one-to-one correspondence between social (S) properties and individualistic (I) properties, I-level explanations may fail to adequately account for S-level phenomena, properties, or facts.Footnote 4 Nonreductive individualism thus shares many of the attractions of nonreductive physicalism: just as token identity between psychological and neuro-physiological states is sufficient for physicalism to hold, so it is enough for individualism that token identity between social and individual states holds. But at the level of types, the existence of psychology and social science as independent disciplines is metaphysically justified.

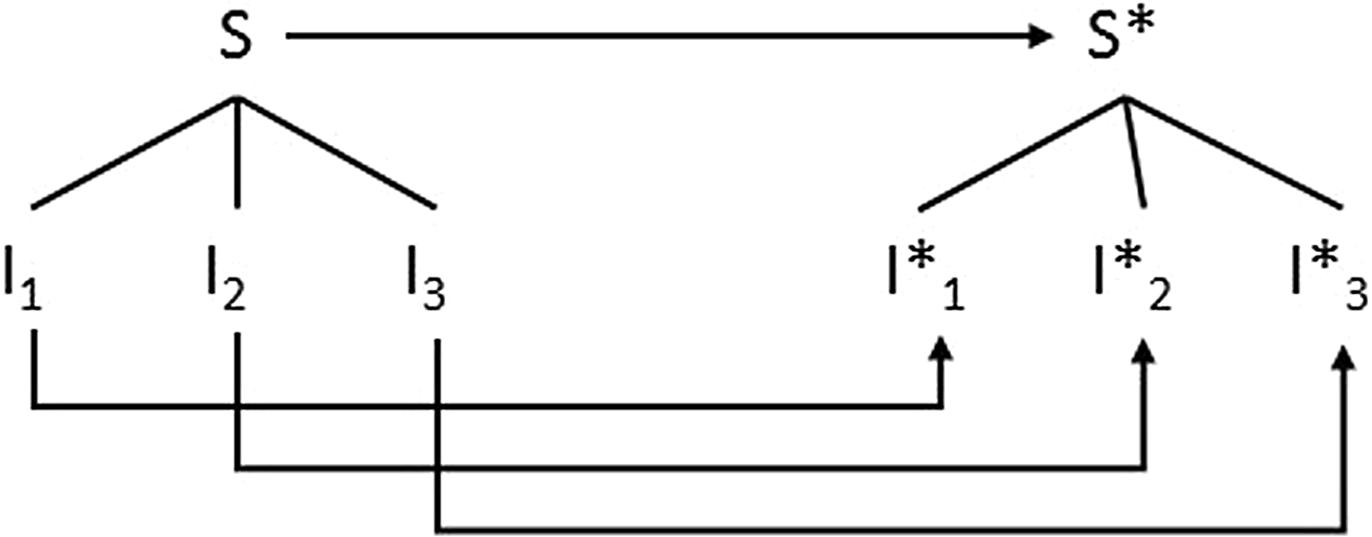

The one-to-many relationship that holds between S-level and I-level properties and laws is usually represented using a version of Jerry Fodor’s (Reference Fodor1974) famous graph (see figure 1). In Fodorian jargon, each S property or law is multiply realizable at the I level.

Figure 1. Multiple realization of S properties and laws (adapted from Fodor [Reference Fodor1974]).

Multiple realization and supervenience make the existence of “holistic” social science not only metaphysically legitimate but also methodologically appropriate. First, we may simply not know enough about the I-level properties to identify genuine causal principles and nomic generalizations. And second, S-level generalizations may capture robust patterns and relations that do not hold at the I level. As Fodor points out, the only way to represent such relations in I language would be to formulate “disjunctive” statements that, however, are not candidates for being proper laws of science.

Because most philosophers nowadays do not subscribe to a covering-law account of scientific explanation, it is advisable to adopt a different terminology from Fodor’s. To be as noncommittal as possible, I will just assume that scientists are interested in the identification of “projectible” properties—the sort of properties that support prediction and explanation (or more generally, inductive inference). Social scientists, in particular, are interested in causal properties, the sort of properties that can be used for policy intervention. So in the remainder of the article, I will speak of robust causal relations and causal properties rather than laws or nomic generalizations. The point to keep in mind—which will play a key role in the argument that follows—is that multiple realization does not concern “generic” properties. It is a thesis about the sorts of properties that are mentioned in the theories of science. Materialists overlook this feature, as we shall see shortly. Before we come to that, however, it is necessary to present the materialist argument in more detail.

3. The materialist argument

The materialist challenge is based on intuitive counterexamples—it focuses on social facts or properties that are not realized by individualistic facts or properties only. Let us start with a simple case: the fact that a piece of paper is a dollar bill (money) depends on its being used as money by the members of a given social group (say, the citizens of the United States). This social fact, however, not only involves a special relationship between the piece of paper and the group members, but it also involves the piece of paper having certain special characteristics—for example, it must have been printed using certain colors, in a certain place, according to specific procedures (those defined, say, by the Federal Reserve). These characteristics are, in fact, what makes a particular piece of paper a token of the type US dollar.

The general implication of such examples is that many social facts seem to depend on facts that are not about humans. Clearly, at the level of tokens, these social facts are not identical to individualistic facts. And at the level of types, they do not supervene on (heterogeneous) individualistic facts only: they supervene on individualistic (I) and material (M) facts. In an early article on OI, Epstein generalizes this point to social practices and the membership of social groups:

It is difficult even to conceive of any satisfactory characterization or explanation of a social phenomenon such as a dance or an orchestral performance or a riot, without incorporating physical factors as well as psychological ones. Likewise, physical factors are involved in the determination of membership in groups as well. It is not only the dance and the orchestra and the riot that involve physical factors, but also the holding of the properties being a dancer, being a cellist and being a rioter. If there were no cellos, then regardless what Yo-Yo Ma and the rest of us thought and did, there would be no cellists. (Epstein Reference Epstein2009, 202)

Another example in the same article concerns the outcome of the 2000 US presidential elections: a key institutional fact—that George W. Bush won the election—depended crucially on the count of votes in Florida, which in turn depended on the number of “hanging chads” (partially punched ballot cards) that were not counted by the tabulating machines used in Florida. As Epstein points out,

These physical conditions for membership—the physical characteristics of ballots—do not seem individualistic. That a piece of paper has a certain thickness, or has some kind of hole in it, is not a property of any individual person. And in fact, nearly any group one can think of has such nonindividualistic membership conditions. (Epstein Reference Epstein2009, 203)

In The Ant Trap, finally, Epstein’s chief counterexample is the dependence of facts about a corporation (Starbucks) on nonhuman facts of various kinds. The example is worth quoting in full:

[C]onsider facts about the Starbucks Corporation. On a typical day at Starbucks, pots of coffee are being brewed, baristas are preparing frappuccinos, cash registers are ringing, customers are lining up, credit cards are being processed, banks are being debited and credited, accountants are tallying up expenses, ownership stakes are changing in value, and so on. At least on the face of it, some of these facts about Starbucks fail to supervene on facts about the people and their interrelations. To be sure, the employees are critical to the operation of Starbucks. But facts about Starbucks seem also to depend on facts about the coffee, the espresso machines, the business license and the accounting ledgers.

Consider what we might want to accomplish in a model of some changing property of Starbucks. Suppose we were to model it through some sort of unfortunate event. Suppose, for instance, there is a freak, late-night power spike at a number of Starbucks outlets, causing the blenders and refrigerators to break, the ice to melt, and the milk to spoil. Suppose that event is the last straw for a financially struggling Starbucks, underinsured as it is. So, when the power spikes and its key assets melt down, its assets no longer exceed its liabilities. Overnight, as the owners, employees, and accountants are asleep in their beds, Starbucks goes from being financially solvent to insolvent.

In this example, the transition to insolvency involves property and equipment, not individuals…. At least at first blush, it is not individuals, or phenomena at the “individualistic level,” that explain this social-level transition. (Epstein Reference Epstein2015, 46)Footnote 5

Two points are worth noticing before we proceed. First of all, materialistic counterexamples against individualism do not introduce any “spooky entities” of the sort that originally motivated OI (Hegelian collective minds, Marxian class interests, and the like). Cards, printing machines, and cellos are not particularly mysterious from a metaphysical point of view. Second, notice that the failure of individualism is not universal. There are plenty of S facts that seem to depend on I facts only. Consider racist John, for example. If we understand racism as sheer prejudice against the members of certain ethnic groups, then John’s racism may well be a social fact that is realized by individualistic (psychological) facts only. The reason is that you do not need a certificate for being racist—in fact, you do not even need to be recognized as a racist in order to be it: your attitudes suffice. (The point can be extended to aggregate phenomena and facts, such as “racism is on the rise in the UK.”)

Nonetheless, cases like those mentioned by Epstein are common enough to be taken seriously. Epstein points out that failures of individualism typically occur when status properties are concerned—that is, properties that involve the attribution of a special role or status to nonsocial entities, such as, for example, “being a dollar bill” or “being the winner of the US presidential elections.” These properties are projections of our thoughts onto the world. As such, they “combine” individual properties (e.g., thoughts, attitudes) with material ones (e.g., papers, buildings, people).

This point, as we shall see, is important: the way in which S properties are conceived is crucial for the argument to go through. In sections 5 and 6, I will show that Epstein has a particularly generous (or loose) way of identifying S properties, which the individualist should not accept. But before we come to that, it is worth reviewing an obvious, natural reaction to the materialist challenge.

4. Materialism as “extended individualism”

Materialist counterexamples do not introduce any spooky social entities. But one may argue that the rejection of spooky entities (or properties, facts) is the raison d’être of OI. So the claim that S facts supervene upon I facts and M facts should not bother the individualist at all. In fact, one may say that materialism is just another version of individualism—to give it a name, we may call it “extended individualism.”Footnote 6 One may quote paragraphs suggesting that early individualists had something like extended individualism in mind and conclude that the materialist is challenging a straw man:Footnote 7 as Hindriks (Reference Hindriks2013) and Di Iorio and Herfeld (Reference Di Iorio and Herfeld2018) have claimed, extended individualism is ontological individualism after all.

Although I have some sympathy for this reaction, it must be admitted that it is easy to find paragraphs in the writings of individualists that indicate a narrower conception of OI. Daniel Little, for example, defines OI as the doctrine that “social entities are nothing but ensembles of individuals in various relations to one another” (Reference Little1991, 183; emphasis in the original). A key tenet of classic individualism, according to Harold Kincaid, is the view that “individuals exhaust the social world in that every social entity is composed of them” (Reference Kincaid1996, 188).Footnote 8 And according to Keith Sawyer,

Ontological individualism is the stance that only individuals exist; sociological objects and properties are nothing but combinations of the individual participants and their properties. (Sawyer Reference Sawyer2002, 537)

Materialists take these formulations as paradigmatic versions of OI (e.g., Epstein Reference Epstein2015, 21; Haslanger Reference Haslanger2020, 1). The question, according to Hindriks (Reference Hindriks2013) and Di Iorio and Herfeld (Reference Di Iorio and Herfeld2018), is whether they are entitled to define OI this way. Because the matter is partly terminological, one could simply introduce a different label for the position that materialists criticize (“psychologism” or “narrow ontological individualism,” for instance). My view, however, is that the materialist challenge has substantial, rather than merely terminological, import: regardless of who endorses either version of OI, the issue is whether material properties play a significant role in social metaphysics or not. Narrow OI says they do not, and materialists disagree. Our goal is to understand what may justify these standpoints. I will argue that materialist counterexamples fail to refute narrow OI, once the latter is understood—correctly—as a thesis about projecible properties. The reason, in a nutshell, is that materialists help themselves to too many properties. Although some of them undoubtedly are nonhuman, and hence nonindividualistic, the individualist should not grant them all. This will be the main point of this article, which I begin to introduce in the next section.

5. The multiple realization of what?

When they theorize, scientists abstract away from many properties of the objects that populate our ordinary, commonsensical world. The phenomenon of multiple realization helps to explain why: if interesting patterns and robust causal relations are scarce at a given level of description, scientists move to another level in order to formulate better (inductively more powerful) theories. In the cases we are concerned with, several familiar properties are deliberately ignored in the theorizing that takes place at the social level. Some of these properties may pertain to individuals, and some may well be materialistic. But this does not mean that they are all on a par: although some of them play a key role in the constitution of S-level causal relations, others are likely to be completely irrelevant.

This distinction between relevant and irrelevant properties is well known to the philosophers who have discussed multiple realization. Larry Shapiro has used corkscrews as a paradigmatic example of functional, high-level kind that may be realized in various ways. As he points out, some physical properties of individual corkscrews are totally irrelevant for the capacity to open bottles:

If differences in constitution suffice to mark differences in kinds of realizations, then we must say that the steel and aluminum waiter’s corkscrews are tokens of distinct kinds of realizations. This conclusion would be too hasty, however. We must first ask what it is about steel and aluminum which contributes to cork removal. Do they differ in their causally relevant properties? They do not. Indeed, it is because they have the same causally relevant properties (for example, rigidity) that each serves so effectively in its role as a waiter’s corkscrew. Steel and aluminum are not different realizations of a waiter’s corkscrew because, relative to the properties that make them suitable for removing corks, they are identical. (Shapiro Reference Shapiro2000, 644)Footnote 9

Examples of this kind may be multiplied at will. Suppose that, as social theorists, we are interested in the relationship between social class and school dropout. Let us further suppose that the relationship between these two macro-variables is, by hypothesis, multiply realized by a variety of micro-mechanisms: some families may not invest in education because they do not believe that it will improve their children’s employability; other families instead may simply lack the money to send their kids to school. Still, there will be other micro-level properties that are completely irrelevant for the realization of the class–dropout relationship. Whether low income is caused by irregular employment or single-parenthood, for example, may be ignored if it does not affect the relationship we are interested in.Footnote 10

The upshot, then, is that only some low-level properties and facts are genuine realizers of the projectible supervenient properties. We can express this idea using Fodor’s diagram (depicted in figure 1). The diagram has a horizontal and a vertical dimension: horizontally, the arrows represent scientific generalizations; vertically, the lines represent “bridge laws,” “correspondence principles,” or “identity relations.” Philosophers nowadays prefer to speak of supervenience, constitution, ontological dependence, grounding, and the like. Still, the important point is that the S predicates represent properties of a special kind: they are the sorts of properties that occur in scientific explanations. They occur in principles such as “ceteris paribus, if the price goes up, the consumption of a commodity goes down” (law of demand), and “ceteris paribus, if the quantity of money increases, the price of commodities goes up” (quantity theory of money). Or to use a Durkheimian example, “during times of socioeconomic change, the rate of suicides is higher among Protestants than among Catholics.” The OI thesis is supposed to apply to these properties, not to any properties whatsoever.

Whereas the friend of OI should be picky about properties, the materialist has an interest in taking a looser attitude. The more S properties the materialist can target, the more likely it will be that some of them turn out to supervene on nonindividualistic properties. One clue that materialists are helping themselves to a wide range of properties is that they tend to talk about OI as a thesis about the supervenience of S facts on I facts. Fact is a generic term, and materialists have a particularly generous conception of S facts, as we shall see shortly.

6. How to be generous about social facts, properties, and objects

The term social fact has a peculiar history in the individualism debate. Durkheim defined social facts as “manners of acting, thinking and feeling external to the individual, which are invested with a coercive power by virtue of which they exercise control over him” (Reference Durkheim1895/1982, 52). For Durkheim, social fact was a technical term (one of the first technical terms of sociology, in fact) and had a clear anti-individualistic connotation. One of Durkheim’s methodological principles for sociology was that S facts are genuinely explanatory. But this principle presupposes a particular conception of social facts: a social fact cannot be a mere aggregate of individual beliefs or behaviors, and it cannot be a mere statistical regularity either. Durkheim claimed that although social facts may show up in statistical correlations—his work on suicide provides several examples—the facts that are relevant for S-level theories must also be causally efficacious. They must explain other S-level facts, as well as I-level facts such as beliefs and behaviors. In general, Durkheim’s conception of social facts was strictly linked with the idea of nonreductionistic social science.

The later literature preserved the term for a while, taking its anti-individualistic connotation for granted. Although it is difficult to identify a precise point in time, things began to change when metaphysicians, not really interested in social science, started to work on this topic. Here, for example, is Greg Currie’s definition of OI, from an article on global supervenience published in the 1980s:

[The global supervenience thesis] says that, whatever complex and reciprocal relations there are between social entities and individuals, it is the totality of individual facts which determines the totality of social facts. (Currie Reference Currie1984, 345)

Currie’s definition of social facts is generous:

Social facts I take, roughly speaking, to be facts about social institutions and roles, and facts about people’s actions, where those actions have a social significance. (Reference Currie1984, 346–47)

It is clear from the context and from Currie’s examples that “social significance,” for him, is not the same as “scientific significance.” The separation of ontological individualism from social science at this point is already underway:

That Smith wanted to vote, that Smith raised his arm, are individual facts about Smith, while the fact that he voted is a social fact about him. For arm raising brought about by the desire to vote does not constitute voting; we need, in addition, a certain social setting. (Currie Reference Currie1984, 347)

Notice that the fact that Smith voted is not a social fact in Durkheim’s sense: it is, if anything, an explanandum rather than an explanans. Arm raising is not the sort of action (or having an arm raised the sort of property) that is likely to occur in a scientific account of voting. No theory in individualistic social science has much to say about arm raising, for the simple reason that arm raising seems to be irrelevant for any interesting generalization that may hold at the S level. Although the raising of my arm constitutes my voting at yesterday’s departmental meeting, it is not something that scientists care about when they theorize about voting.

A generous attitude about social facts and related concepts has since become pervasive in the social ontology literature. Sometimes it becomes manifest as a concern about the ontology of “social objects,” sometimes as talk of generic “social properties.” In most cases, philosophers forget to mention that not every object, property, or fact is relevant for the individualistic project. In fact, it is questionable that individualists should be concerned about the constitution of social objects—especially ordinary objects such as dollar bills or ballot cards. And it is also questionable that they should be concerned with any S or I property whatsoever. They should, on the contrary, be concerned with those properties that are relevant for the formulation of social scientific theories.Footnote 11 Of course, some of these properties may also belong to our commonsensical picture of the world. But they will be relevant for the OI debate only insofar as they are scientifically relevant (projectible).

Kincaid, some time ago, issued a warning about the vagueness of “fact talk” and the importance of paying attention to science:

Talk of “facts” gets clearer if we specify particular theories and their basic categories. Then determination and supervenience hold respectively that the facts about A determine the facts about B in that once all the truths in the theory of A are set, then so are the truths of the theory about B or, in other words, the B truths are fixed by the A truths. (Kincaid Reference Kincaid, John, Marciano and Runde2004, 302)

What sort of cases does he have in mind? “Participation in elections is larger in countries that use proportional electoral systems than in countries that use majoritarian systems” may be an example of such a B truth. “Candidates tend to converge on centrist platforms when they compete in elections with majoritarian systems” may be another one. These are not social facts taken in isolation but facts that are embedded in scientific theorizing. As Hugh Mellor once noticed, “sociology, if anything, is a body of law-like generalizations, not a string of particular social facts” (Reference Mellor1982, 72).

Another way to put it is that loose talk of “social facts” and “individual facts” invites privileging the vertical over the horizontal dimension of Fodor’s graph (see figure 1). It invites focusing on how I properties realize S properties in isolation, so to speak, rather than how I-level causal relations (I→I*) realize S-level relations (S→S*). Ignoring the horizontal dimension is essential for the materialist and is exactly what the individualist should not concede.

To nail this point more clearly, let us have a closer look at one of Epstein’s examples. The electricity peak that sends Starbucks into bankruptcy is not something that is likely to be mentioned in any economic theory because economics abstracts away from the details of individual firms’ production technologies. Its models capture relationships between general properties, such as profit, price, revenue, and various kinds of costs (fixed and variable, average and marginal, short- and long-run costs). Although an explanation of Starbucks’ failure that appeals to a technical problem may be adequate for some purposes, such as a posthumous history of the Starbucks corporation, singular physical events are relevant for social scientific explanations only as triggers of particular causal processes. As far as economic science is concerned, the melting of Starbucks’ material assets is an event that affects the properties revenues, costs, and long-term profitability, which in turn explain or help us predict the subsequent course of events. What really matters is Starbucks’ capacity to generate value for its stakeholders, and value is an individualistic property, according to standard economic theory.Footnote 12

To recap: the goal of theoretical science is to formulate general principles that can be used across a variety of situations. In order to do so, scientific theories often abstract away from several familiar properties of ordinary objects in order to focus on other properties with broad causal and explanatory power. It is during this process of abstraction that material properties are typically dropped in social science theorizing.

Now, materialists may protest that the existence of social scientific theories that refer to projectible material properties cannot be ruled out a priori. This remark is correct, of course, but cuts both ways. For their argument to take off, materialists ought to convince us that material properties are explanatory relevant—namely, that they do or will play a role in social science. Because I do not think that philosophers are in a good position to predict the future of science, I will just comment on how materialism fares with respect to current social science. Although I cannot review every possible case, I will express some skepticism using the most plausible candidates for materialistic social science that can be found in the literature.

7. Materialistic social science?

Economics is the science of the production and distribution of wealth. As Kincaid (Reference Kincaid, John, Marciano and Runde2004) has pointed out, it is not outrageous to think that physical objects may play a role in a discipline of this sort. But, he continues, “deciding what these physical entities are and how they should be conceived is a substantive economic issue” (Reference Kincaid, John, Marciano and Runde2004, 302). Take technology, for example. Economists define technology in a very abstract fashion, as encompassing any humanly controlled factor that contributes to economic growth, apart from labor and investments. The rationale behind this definition is that technology comes in many different guises, but for the purposes of economic theorizing, its material realizations are largely irrelevant: what really matters is whether technology generates efficiency gains. Thus, in the Oxford Dictionary of Economics (Black, Hashimzade, and Myle Reference Black, Hashimzade and Myles2009), technology is identified with knowledge, and in the influential New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (Mokyr Reference Mokyr, Steven and Lawrence2008), it is identified with propositional knowledge. The case turns out to be unfriendly to the materialist after all. Not only is it entirely possible that the relevant properties (the growth-producing properties) have little materiality, but a mass of work in economics supports the idea that equating technology with knowledge only invokes properties of individuals.

Now, materialists could say that current economics is not a good guide to the identification of projectible properties. They could claim, for example, that ignoring the material properties of social objects leads to weak theorizing or to bad explanations of social phenomena and events. This strategy must be handled with care, however: it is not enough to point out that some social scientific theories have a patchy predictive record, for instance, for we already know that the generalizations of the special sciences are not exceptionless. In a sense, this is the price we are willing to pay when we move up one level in the scale of explanation, from a fundamental to a special science (cf. Fodor Reference Fodor1974). What anti-individualists must do, if they are serious, is show that introducing material predicates would result in an improved social science—that it would endow social theory with more predictive and manipulative power, simplicity, wider scope of application, and so forth.

Can social science help the materialist? Economics is not, after all, the only science that deals with technology. Sociologists have a long-standing interest in this field, and some of them have been willing to assign a central role to nonhuman entities and properties. The best-known and discussed example is actor-network theory (ANT), an approach developed by Michel Callon, Bruno Latour, and their collaborators since the 1980s (e.g., Callon Reference Callon and Law1986; Latour Reference Latour1993, Reference Latour2005; Law Reference Law and Turner2008). The central idea of ANT is that social processes in modern societies are constituted by interactions between human and nonhuman objects. Natural entities (rivers, microbes) and technological artifacts (railways, nuclear plants) are represented as nodes of a network that also includes human actors. The fundamental ontology of ANT elides the distinction between human and nonhuman reality, assigning “agency” to each and every element of the network.

Is ANT a genuine example of materialistic social science? The proponents of ANT, unfortunately, have repeatedly claimed that ANT should not be evaluated by the standards used for traditional scientific theories. ANT does not aim at formulating causal generalizations, to begin with, but starts from the presumption that every social event is unique. Because networks are constantly changing, no theoretical generalizations are possible.Footnote 13 ANT is better conceived as a methodology commending a certain way of looking at social processes. It is a heuristic for the construction of case studies rather than a theoretical framework pursuing broad explanatory goals.

A devoted materialist may still criticize ANT for not being ambitious enough. There are enough regularities in the social world to suspect that relatively stable causal mechanisms are operative, and such mechanisms may comprise both human and material elements. Elder-Vass (Reference Elder-Vass2017), for example, has claimed that such an ontology is internally coherent and backed up by empirical studies of “cognitive distributed systems.”Footnote 14 Admittedly, however, this research program is at an early stage of development: it offers some case studies and an ontology providing guidance from the background—but little scientific theory in between. Until a reasonably precise, generalizable account of nonhuman and human interaction is developed, it is hard to say what role nonhuman properties should play in a materialistic social science. Will they play the role of mere “triggers,” as in the Starbucks case? A subordinate role as “scaffoldings” for human cognitive faculties, along the lines suggested by the literature on extended cognition? Or will they provide general principles upon which the explanation of different social phenomena can be built?

The upshot is that debates about OI look suspiciously like debates about the future of social science. Implicitly, they are also debates about the standards of explanation that social science must satisfy. Some are happy with historical or singular explanations, whereas others believe that a future materialistic social science will be able to produce more robust causal explanations. Perhaps singular case studies that mention nonprojectible material properties or facts may coexist with other forms of explanation based on general, systematic theorizing. A science of this kind needs rigorous criteria to evaluate its claims and ensure that they capture real properties and relations in the social world. In any case, arguments like Epstein’s are bound to fail: the fate of materialism is inextricably entangled with the explanatory successes (and failures) of social science rather than with developments in social metaphysics.

8. Concluding remarks

The philosophical community is divided by an increasingly deep rift between those who think that metaphysics can (and in some cases should) be done independently of science and those who think that science should be our primary source of information about the world. Work on the ontology of ordinary objects tends to belong to the first camp, and social ontology has been steadily moving in this direction. Although the ontology of ordinary objects may be of independent interest, however, its contribution to our understanding of social reality is by no means obvious. This article has focused in particular on ontological individualism. I have argued that OI is primarily a thesis about the relation between the properties that feature in scientific theories. Hence, ordinary objects and their properties are relevant to OI only insofar as they belong to the explanatory framework of social science.

In spite of naturalists’ reminders (e.g., Kincaid Reference Kincaid, Zahle and Colin2014), this point has been almost forgotten in the literature. Perhaps individualists are the victims of their own argumentative strategy. If all S properties (or facts) supervened on I properties (facts), then obviously all S theories would supervene on I theories. But asserting the antecedent (“all S properties supervene on I properties”) opens a gap that materialists can exploit. It is sensible, then, to remember that individualism is first and foremost a thesis about projectible properties, not about facts or properties “in isolation.” We must be selective about the sorts of properties that count, and we must pay attention to social science when we look for counterexamples.

The key question is: What kind of projectible properties are multiply realized, and how? The whole point of focusing on S-level properties is that they capture patterns that do not hold or hold in a much more cumbersome way at any lower level. So we should expect S theories to abstract away from many lower-level properties. The materialist cannot just pick one of these properties and say, “It is not individualistic.” Individualism is in trouble only if the relevant S properties are projectible in virtue of their being instantiated in some material property. Or symmetrically, only if the causal, explanatory power of some S properties is not grounded in any I properties.

A key assumption has tacitly informed the whole discussion so far, namely, that scientific explanations rely on general or generalizable causal theories. This is not an innocent assumption, and the materialist may want to challenge it. There are multiple understandings of “theory” in social science, as well as disagreements about the concept of explanation. Some materialist programs in social science invoke alternative notions of explanation and explicitly shy away from claims of generality. Others are more optimistic about the prospect of uncovering general causal mechanisms that cut across the human–nonhuman divide. But it is fair to say that these attempts have produced interesting philosophical reflections, some empirical case studies, and limited systematic theorizing so far.

Such a perspective, in any case, presupposes a serious engagement with social science to assess its ambitions and successes and to guide its future progress. Naturalists should certainly welcome such a project and should encourage serious philosophers to carry it along in collaboration with scientists.Footnote 15 Until materialistic social science comes into being, we have only scant evidence against OI. Metaphysical speculation indicates that material properties might be causally relevant, but only successful (explanatory) social science can establish that they are.

Acknowledgments

I’m grateful for the hospitality of the members of the Department of Philosophy at Erasmus University Rotterdam, where this article was originally conceived. Previous versions have been presented at the 2018 meeting of the International Society for Social Ontology in Boston, at the University of Barcelona, and at the University of Belgrade. I thank the members of these audiences; three anonymous referees; and especially Filippo Contesi, Brian Epstein, Frank Hindriks, Harold Kincaid, Richard Lauer, and Julie Zahle for their comments and suggestions. This research was funded by the Department of Philosophy “Piero Martinetti” of the University of Milan under the project Departments of Excellence 2018–2022 awarded by the Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR).