Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 April 2022

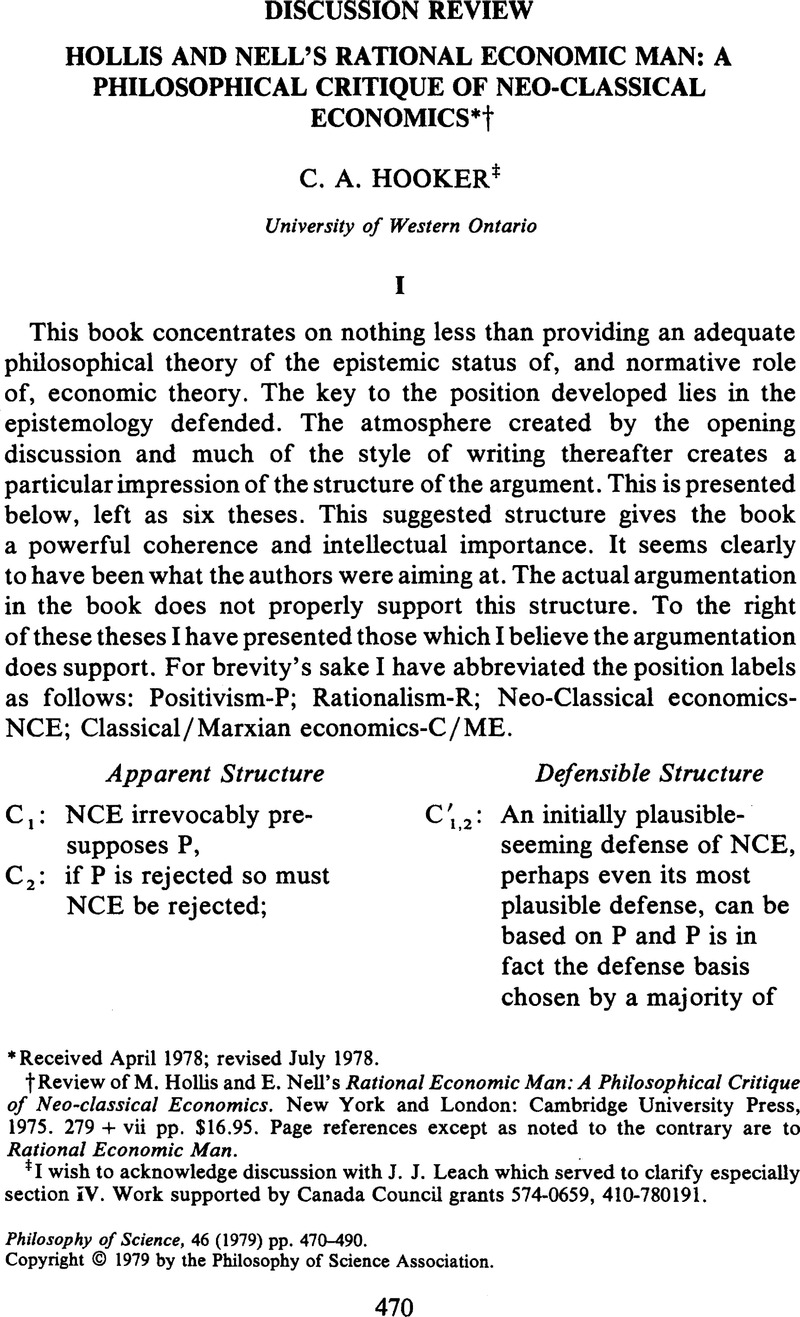

Review of M. Hollis and E. Nell's Rational Economic Man: A Philosophical Critique of Neo-classical Economics. New York and London: Cambridge University Press, 1975. 279 + vii pp. $16.95. Page references except as noted to the contrary are to Rational Economic Man.

I wish to acknowledge discussion with J. J. Leach which served to clarify especially section IV. Work supported by Canada Council grants 574-0659, 410-780191.

1 Though I still could not accept C′4 or the stronger form of C′5, I otherwise find the claims quite acceptable. Space limitations restrict me to a brief sketch of the reasons for my judgements.

The argument of chapters 1–5 only establishes that P is a sufficient (if faulty) basis for defending NCE and that NCE economists have in fact largely resorted to P to defend their position. The stronger, necessity conclusion results from this argument: C4, R entails C/ME, C6. But that R entails C/ME is a stronger claim than C5 and quite clearly a stronger claim than H/N would wish to defend.

Note. C2 might be supported as follows: C3, C4, R cannot (does not) support NCE. There is an ambiguity in the claim, expressed by the parenthesis, which concerns the nature of R for H/N (see below) but, setting this aside, H/N would probably agree to defending C2 in this manner. In Section II, I attack and reject C4 and R, and do so in a way which leads also to a rejection of the last premise here.

There is the outline of a defense of the crucial C4 buried at the end of chapter 6, otherwise it goes unsupported (H/N's admission, p. 162). There and in the subsequent appendix H/N briefly consider a “conceptual pragmatism” which they reject. The suggestion is then made that these two “variants of empiricism” essentially exhaust the epistemic alternatives to R and so R alone survives. This suggestion I find most implausible. Many philosophers have devoted considerable effort to developing a strongly non-E and non-R epistemology. (For my own efforts see Philosophy of Science 42 (1975), 152 and Synthese 26 (1974), 409; 27 (1975), 245. In the latter piece I was especially concerned to show how deep the cleavage with E could be without embracing R.) Perhaps these alternatives all ultimately fail of coherence, as H/N suggest, but this is as yet a long way from being established. I conclude that C 4 is inadequately supported.

C5 is undefended in the text. The closest one gets to C5 in the text is something like: the only viable way to defend C/ME is R. Neither do they argue for this latter claim (except, perhaps, in trivialized form by claiming C3 and C4). All they do is simply adopt R and use its generalized authority to pick out what they consider are the economic truths. Certainly the majority of C/ME proponents have wanted/do want their doctrine to stand on its own non-R feet (because they are, e.g., Marxist materialists).

Equally, C6 remains undefended-at least the portion outside the parentheses. For although they develop arguments in favor of C/ME specifically, they nowhere argue that the field of economic theory is exhausted by NCE and C/ME.

2 H/N evidently find abandoning foundations so distasteful that they cannot resist creating a straw man through caricature. A good example is found on p. 159: “A causal law becomes simply a general statement which it suits us to hang on to. The testing of predictions becomes the occasion for deciding which parts of our theory we are most attached to … Nothing remains independent of our thought. A true belief is true only insofar as it coheres with all others we choose to believe at the time.” The italics are mine. Compare p. 164: “… according to Pragmatism, truth is not objective and cannot be objectively pursued.” Now it is simply false that Pr is committed to these doctrines and naive to believe so. Pragmatists were inspired by an evolutionary, naturalistic realism and it would be an undergraduate exercise to disentangle the truths partially represented in these claims from their overall falsity. I have myself developed a non-foundational, evolutionary epistemology which is explicitly inconsistent with each of these claims and in so doing I think it safe to claim the support of Pierce, Dewey, Quine and other illustrious ones. Moreover, to introduce such claims as consequences of Pr without any attempt at argument or even rudimentary historical exposition is pernicious, a resort to ‘persuasive writing’ that is beneath the dignity of the remainder of the book.

There is no space here to recapitulate a full case for what I have called Evolutionary Naturalistic Realism (ENR)—see references above—suffice to say that the setting is the essentially Darwinian evolution of life, without revelation or any other guaranteed access to the truth, without even any guaranteed accurate conceptual scheme in which to attempt description of the truth. In these circumstances it is surely proper (rational?) to hold everything up to doubt and testing, and this attitude can never be removed. But precisely the evolutionary setting provided means that there is a world independent of human beings and that living in it and describing it with some degree of accuracy are not purely matters of taste. The urgent question is: by what best method can creatures born in evolutionary ignorance proceed? To ignore this serious driving core of Pr is to distort it beyond recognition (or interest). H/N are acute enough logicians to work out the more accurate versions of their remarks. E.g., a fairer version of the penultimate sentence quoted above is: “Though truth is objective, our only criteria of rational epistemic acceptance concern internal relations among claims and the experienced quality of life to which a given body of claims leads.” Though such claims still require lengthy discussion, once the distinction between truth and acceptance is made H/N's mis-descriptions can be seen for what they are.

3 There is an initial version of the argument contained in the paragraph beginning 1/4 from the bottom of p. 160, but this is too shot through with mis-statement to warrant pursuing it (cf. note 2). H/N then proceed:

“To put it more formally, let E be a statement to the effect that experience shows that a revision is needed in our scheme of beliefs; and let L be a statement to the effect that we cannot retain both belief P and belief Q. Can we or can we not revise E and L? If we can, then it is true neither that our beliefs face the tribunal of experience nor that action is needed when they do. If we cannot then it is false that ‘no statement is immune to revision’.” (p. 161) I concede the second alternative of this dilemma. Let us concentrate then on the first alternative.

Consider the second of H/N's claims. Trivially, altering the logic so as to accept “Retain P and Q” is exactly a relevant action. And an extensive action at that, since a revision in the rules of inference would undoubtedly be required. Just such proposals are currently being made by some quantum theorists. But H/N seem too blinkered by their rationalism to even contemplate the possibility of altering the logic as a response to experience. It is on examples such as this that their positive arguments for R founder—see below.

Now consider the first consequence which they draw, that our beliefs do not face the tribunal of experience. It is crucial to the evaluation of this claim how one understands the term ‘experience.’ Understood narrowly, we have here to do only with statements of the form “D requires a revision of beliefs,” where D is some observation-decidable description. But such statements can certainly be revised on good grounds without thereby impugning experience as an ultimate constraint on, and guide to, theorizing. (We may, e.g., revise D, revise the conceptual connections between the concepts in D and those elsewhere, and so on.) If we construe ‘experience’ more widely, one possible version of the claim would be “Descriptions of experience are components of rules of acceptance” (and so don't face the tribunal of experience). Under this proposal, H/N's sentence can certainly still be held open to revision, but now it is crucially important to distinguish meta levels in the hierarchy of doctrine. The proposed version of H/N's claim is, let us say, a level 1 claim (statements in scientific theories being level 0 claims). A theory of rational decision making at level 2 allows the revision of this level 1 claim (and under conditions quite familiar to anyone in the trade). Level 2 rules for rational procedure concern the modification of what would ordinarily be called methodological (level 1) rules under persistent failure to deal satisfactorily with problems. Within an evolutionary, naturalist realist (ENR) framework, (see references in note 1) the various levels interact. Thus, so long as we insist upon precision of statement, there is a straightforward (and historically insightful) manner in which to understand the revisability of these sentences without generating H/N's extreme consequences.

The importance of such meta discussions, and of meta doctrine in general, escapes H/N's book. I have had occasion to emphasise, e.g., that the manner in which ENR is emphatically non-empiricist can only be represented at the meta (1) level—see references, note 1. But H/N happily class Pr as a version of empiricism. Also, they resort to arguments of the sort “Let us apply this principle to itself …” in a fashion which entirely ignores this distinction—e.g., at pp. 161, 178. Only a naive notion of acceptance, and hence of revision, e.g., would “urge the seemingly damning results of taking the statement ‘no statement is immune to revision’ and asking whether it is immune to revision.”

4 That decisions are currently made ‘intuitively,‘ without explicit, quantified rules being consciously obeyed, is of course obvious, but (notoriously) not in itself grounds for disbelieving the existence of such. Consider in this connection the development and use of spatial perception, language, even logic; we are only barely beginning to understand the rich internal structures of these human accomplishments—why not for science also? Historically, we have also barely begun upon the enterprises of science and theory of science, yet some impressive progress has been made, and a larger number of people than ever before are devoting their talents to rendering these notions more precise. Certainly H/N offer us nothing substantive in favor of their conclusions.

Moreover, H/N don't take seriously the key Pr notion that all meta levels are open to criticism, are to be experimented with; the difference, in general, being only one of the time-scales involved (cf. ENR references). H/N conclude, e.g., from the availability of three alternative economic models of decision making, that Pr can have no rational grounds for choosing between them (p. 169). The Pr reply is obvious: (it will take longer, but) experience with, i.e., testing, these alternative models will reveal their merits and defects and so lead to some decision among them, or perhaps to another alternative entirely—just as happens with scientific theories themselves. We learn what it is to be rational just as we learn everything else. Again, there is not the space here to enter a detailed discussion of the reasonableness and persuasiveness of this response, but I hope that it will at least be clear that there is a consistent, coherent Pr response.

5 Such evidence includes, e.g., what is known about the evolution of language and the brain and about the diversity of conceptual categories and linguistic structures across languages and the evolution of categories and structures within languages. Though once again detailed presentation here is precluded, the conclusions I draw from such evidence are: (i) language is but one specialized function of a brain/mind whose primary focus is elsewhere: bodily action; (ii) conceptual categories and other linguistic structures are largely and perhaps wholly experimental inventions which have evolved to reflect the particular circumstances faced by particular peoples, and (hence) (iii) languages embody in their structures what amount to contingent theoretical conjectures concerning the nature of reality. From this perspective R can draw no sustenance whatsoever from the appearance within languages of systems of claims which must be classified as ‘strongly true’ within those languages, no matter how ‘self-evident’ and deeply entrenched they may appear to be. Nor, obviously, is ENR/Pr forced to adopt the analytic/synthetic distinction and insist on the empty analyticity of such truths, as P is, for the foregoing perspective on language really undermines that distinction, as well as leading to the representation of the truths as theoretical conjectures. Thus the reasons for rejecting the analytic/synthetic distinction ultimately lie in a theory of language, not in the mere possibility of epistemic dodging, as H/N suggest (cf. pp. 154, 159).

Though it might be possible to exempt logic from this treatment, the more consistent and thoroughgoing position holds the same experimental status for logic as well. And recently there has begun emerging the basis for understanding how logic is itself a theoretical conjecture and what the conditions are under which it might be changed. (See, e.g., my (1978) The Logico-Algebraic Approach to Quantum Mechanics, Vol. II, Reidel and the references therein.) Such considerations undermine any prima facie claim by R that logic or mathematics should be counted in its favor.

H/N's defense of logic and mathematics as founded on necessary truths is found, essentially, on p. 150. It is quite inadequate to the task. Faced with alternative systems of geometry, e.g., as the classic evidence that abstract mathematical systems do not directly capture physical reality, they resort to two responses: (i) there is a real definition of geometry which captures the essence of that concept and precludes alteration of axioms that violate that conception, (ii) the axioms can be conditionalized in the absolute form “In L, A → T,” where L is “our logic” and A and T the axioms and some theorem, thus yielding necessary truths of logic/mathematics. But, re (i), mathematicians have consistently extended the radicalness of the ways in which they have altered Euclid's axioms, what then is to count as a geometry? Any definition looks more and more like a convenience and less and less like an essence-capturing definition. The ancient concept, appropriate to the everyday experience of Homo Sapiens, fragments and diversifies under new problems and theories. To reify it into an essence is just to fossilize past conjecture. And, re (ii), unless “our logic” can be shown to focus in upon a system of necessary truths, the reply carries no force. But precisely the point of drawing attention (earlier) to quantum logic is that there has emerged here a logic, a system of inference, evidently self-consistent on its own terms and irreducibly different from any of the traditional logics (classical, intuitionist, modal, many-valued). In the face of such developments the concept of “our logic” also fractures and diversifies. Though H/N have more to say about logic/mathematics, I do not perceive anything else they say as providing better arguments than those examined above. The ENR/Pr notion of interpreted, applied logic/mathematics as a system of conjectures is left both undefeated and increasingly plausible.

6 Insofar as the mathematical case is plausible, the two cases are importantly unlike. All that is required to be known in the mathematical case is whether or not a certain proof is constructible, independently of what is claimed about the status of the mathematical axioms or the logic employed in the proof. But our only evidence for believing, say, of a system of axioms for economics that they too are necessary truths is that the resulting theory accounts for all relevant phenomena, it is not just a question of a purely ‘internal’ formal construction.

7 Consider for a moment Hoyle and Bondi's ‘steady state’ cosmology. In this theory hydrogen is assumed continuously created throughout space ex nihilo (or anyway ‘ex the quantum vacuum state’). The theory was taken very seriously, indeed it was once favored over rivals, but it has now, alas, largely been abandoned. It was not abandoned because it was found incoherent, but because the weight of evidence went against it. Now suppose we elaborate a little on the notion of spontaneous emergence from the vacuum state; specifically, assume that the material commodities of advanced capitalist economies spontaneously emerge from the vacuum state, perhaps complicated by the requirement that the emergence is blocked or nullified by thoughts deviating from Milton Friedman's line. Of course energy and matter conservation are violated, as they are violated in Hoyle and Bondi's theory and as they were violated in the early quantum theory of Bohr, Kramers and Slater and in many other serious proposals, but this only shows that such principles are not necessary components of our concepts of matter and cause. (Surely?—or will H/N claim divine right to arbitrate on what is serious, coherent science?) One could multiply objections along these lines, but surely this is enough to destroy all such suggestions of a ‘transcendental deduction.'

8 What becomes of the claim that “production necessarily involves the using and using up of materials” in the whimsical world concocted in note 7? And in case it be suggested that there is no production in that world, it would be easy to modify the theory so that each real (i.e., H/N) production was exactly compensated for. And a thousand other ‘counter example worlds’ of this sort suggest themselves for every claim in the foregoing quote.

9 See Lowe, A. (1965) On Economic Knowledge, World Perspectives Vol. 35, New York: Harper and Row. And Heilbronner, R. (1969), (ed.) Economics and the Public Purpose, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.; Prentice-Hall. I myself would want to modify Lowe's model, but it suffices as example here.

10 H/N don't emphasis this, however; e.g., it is missing from the second horn of their dilemma for NCE on p. 240. Could it be that H/N themselves are guilty of ‘abstracting from the essence of reality’ by regarding parenting as mere biological reproduction and education as the mere production of skilled workers?

11 In all fairness, H/N can hardly be blamed for not writing a definitive work on everything. With respect to what they do write, there is no doubt that further criticisms may be made: that the detail of some of their specific attacks on P is dubious, e.g., at pp. 41–2 (a doubtful way to deal with chemical predictions), p. 76 (a non-sequitur), pp. 87–8 (what can the objection be? Refusal to use the predicate calculus?), pp. 89–94 (why can't P also have access to social rules and claim that they entail the following of the maximization rule?) and like criticisms. But these concern only the details in a way which no longer affects the overall thrust of the argument.