One thing that political scientists reliably do is tease out the underlying structure of a nation’s politics and use it to interpret political events as they unfold. One thing that Donald Trump reliably does is flummox political scientists with words and actions that they do not recognize as conventional behavior. But should this disjunction be laid at the doorstep of a cantankerous president, or is it more appropriately seen as simple interpretive failure by those (flummoxed) political scientists? Asked more politely, can the Trump presidency be seen generally as one among several logical results of a political structure recognized consensually by a great many analysts, even as they ignore the inescapable link between structure and outcome?

From one side, the first tweeting president, with a willingness to reach below the belt and a propensity to indulge (frequent) changes of his own mind, offers substantial evidence—bait—for those who prefer the idiosyncratic side of this particular dialectic. But from the other side, the extent to which every presidency is idiosyncratic is precisely the sense in which political scientists have nothing distinctive to say. So perhaps we ourselves should begin by saying what this interpretive effort is and is not. It is an attempt to isolate the broader structure of modern American politics, to ask about the role of that structure in shaping the electoral fortunes of a Trump candidacy and the policy products of a Trump presidency. As such, it cannot be a focus on the important ways in which Donald Trump is different, unique, or truly “Trumpian”.

Rather, it is a focus on the equally important ways in which his candidacy, election, and governance embody familiar, almost predictable, patterns. So it certainly cannot be a projection of this particular president’s impact on societal (or even just political) norms—often more a Rorschach for the anxieties of social scientists than a genuine piece of social science. Which is not to dismiss the specific game-changers that are vaguely visible on the current horizon—perhaps Special Counsel Robert Mueller really will confirm one or another of the alleged smoking guns from the annals of campaign behavior, financial connection, or foreign involvement—but only to say that these cannot well be systematically projected.

In that light, the first section of this particular interpretive effort begins with the structure of American politics in the years following the Second World War, years treated in their time as a period cursed by partisan gridlock and policy dithering, but now recalled nostalgically as a time when politicians could build coalitions and make policy—as well as being a golden age for American political science. Beginning with this period has two clear advantages. On their own terms, these years provide the necessary template for comparisons to a modern successor world. In the process, they demonstrate how an ongoing political structure shapes the electoral outcomes and policy processes of more than one individual president within its era.

The next section then leaps to the most recent quarter-century, from 1992 to the present, asking again about the (changed) structure of American politics, along with its associated electoral pattern and its diagnostic policy process. A contemporary political structure is always more challenging to elicit than one which offers, say, the fifty years of historical perspective informing the first section. Yet the same critical elements—party balance, ideological polarization, and substantive conflict—should be able to connect this modern structure to the electoral contests of its period as well as to the policy-making process that really contributes its diagnostic character.

In the third section, the products of such a comparison thus drop the Trump candidacy of 2016 into a more fully developed framework. A fourth section permits dropping the Trump presidency into this framework. Within it—to cut to the chase—the election of 2016 appears less an anomaly and more as one of a small set of recurrently available alternative outcomes, albeit not the most common variant. Even more to the point, this framework connects the policy-making process of the Trump Administration to the three presidencies that preceded it—those of Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama—again making it look even less like an anomaly and more like a distinguishable part of an ongoing whole.

Our interpretive effort closes with a brief fifth section by asking what such an analysis would imply going forward, especially regarding the 2018 elections.

The Old World of American Political Structure

The first critical aspect of a continuing American politics in the initial postwar years was the one that was most strikingly different from the years before the Great Depression and the New Deal—the appearance and then the institutionalization of a Democratic voting majority nationwide. No serious analyst missed the initial, jarring shift between a solid Republican majority in the 1920s and a huge Democratic edge from 1930 onward.Footnote 1 On the other hand, observers at the time debated its lasting character, and recent research has suggested that this new Democratic majority was not really institutionalized until the early postwar years, beginning with the re-election of President Harry Truman in 1948.Footnote 2

Figure 1 offers the party balance from the National Election Study for this period in both canonical ways, first as an answer to the single question, “Do you think of yourself as a Democrat, a Republican, an Independent, or what?”, then as an answer to the two-fold query probing the strength of attachment among confessed partisans or the partisan leanings of those who deny any such an initial identification.Footnote 3 What emerges for the late New Deal era is a solid Democratic majority, seen at its most basic in figure 1A, where the aggregate edge over the Republicans is impressive, and then with internal distinctions in figure 1B, where the Democrats can nearly dispense not just with all of the Independents but with most of the Leaning Democrats too. This suggests a world in which these Democrats were the default choice to gain national majorities, and such a world was clearly in existence: the Republicans succeeded exactly once between 1932 and 1968 in wresting away the presidency, courtesy of Dwight Eisenhower, exactly twice in that same stretch—1947–1948 and 1953–1954—in wresting away control of Congress.

Figure 1 Party Identification in the Nation as a Whole: The Late New Deal Era

Data: American National Election Studies, University of Michigan, and Stanford University. ANES Time Series Cumulative Data File (1948–2016). Ann Arbor, MI

On the other hand, these bedrock facts are true but extremely misleading when the task is unpacking the larger structure of American politics in this period. For where party identification suggested a huge break with the partisan past, courtesy of the Great Depression and the New Deal, the ideological balance within those parties suggested that it was the New Deal years that had been deviant, with the postwar world returning to an older, quintessentially factional patterning to American party politics.Footnote 4 Congress was the institutional venue that allowed this underlying pattern to surface in an easily measurable fashion, just as Congress was the venue that would confirm the place of factional politics in the making of postwar policy. And there, the policy analyst needed four factions, not two parties, in order to talk about this postwar process of policy-making.

While the number of potential factions was in some sense limitless if the analyst was willing to micro-analyze the partisan clusters of the time, each party could in fact be characterized through one dominant and one secondary faction.Footnote 5 For the Democrats, Northern Democrats were the dominant faction and Southern Democrats the main secondary alternative. For the Republicans—effectively missing in the South—a better distinction was between Regular Republicans in the nation as a whole and Northeastern Republicans as the main secondary alternative. Figure 2 offers these four factions for our chosen years, in essence the late New Deal era, along with their distribution in the short high New Deal that preceded it.

Figure 2 Factional Composition of the Two Parties in Congress: The House in the High and the Late New Deal Eras

Data: Leweis, Jeffrey B., Keith Poole, Howard Rosenthal, Adam Boche, Aaron Rudkin, and Luke Sonnet (2017). Voteview: Congressional Roll-Call Votes Database. http://voteview.com

The high New Deal era is helpful in underlining the scale of the partisan earthquake that arrived in the aftermath of the Great Depression. Yet today, its two lonely Congresses of 1935–1936 and 1937–1938 show more clearly the change in factional alignments that succeeded it, since these two Congresses are still the only ones in all of American history to be characterized by Northern Democratic majorities. Beginning in 1938, a longer-lived world (re)emerged, one that would be central to policy-making throughout the immediate postwar years. This new partisan world had two dominant characteristics. First, it featured a partial revival of Republican prospects nationwide. If the Republican Party never recovered its pre-New Deal health during these immediate postwar years, it did reliably cut the aggregate Democratic advantage. But second, this new political era went on to emphasize the importance of the main secondary factions, the Southern Democrats and the Northeastern Republicans, inside their respective national parties.Footnote 6

It was this second aspect of change that would be central to policy-making for the long generation after the Second World War. With social welfare continuing as the dominant policy realm in American national politics, Northern Democrats would continue to square off against Regular Republicans as the left and the right on economic and welfare policy.Footnote 7 Yet victory or defeat for the Northern Democratic faction, and indeed the specifics of most of the policy secured by either side, would be determined by the success of these Northern Democrats in holding their Southern brethren on side or in drawing Northeastern Republicans across the line—just as victory or defeat for Regular Republicans would reside in holding their Northeastern colleagues on side or in attracting Southern Democrats.

On the other hand, that still drastically understates the increasing complexity of the policy bargaining that characterized American politics during these years. For where the high New Deal had centered overwhelmingly on issues of social welfare, these issues were now joined by two other major substantive domains for policy conflict. Foreign affairs moved to the center of American politics during the Second World War and stayed there as the United States became a moving force in the long Cold War that followed.Footnote 8 And civil rights welled up within American society rather than being imposed from the outside, but was likewise intrinsic to policy conflict during the immediate postwar years.Footnote 9

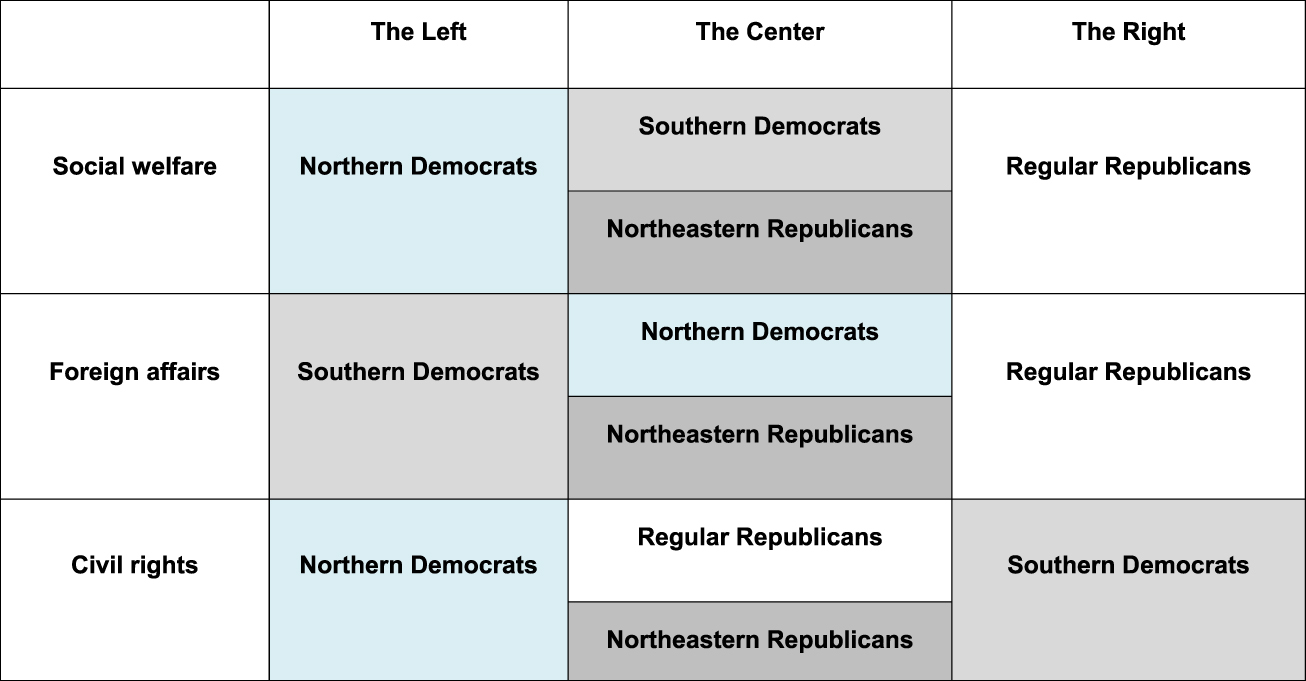

That might have been enough to make the policy-making process additionally complex in a major way. Yet this still understates the complexity of that process, as synthesized in figure 3, because each of these three policy domains aligned the four main party factions in a different fashion. We have already noted that social welfare pitted Northern Democrats (the liberals) against Regular Republicans (the conservatives), with Southern Democrats and Northeastern Republicans as the swing factions. Yet foreign affairs arrayed these factions quite differently, pitting Southern Democrats (the internationalists) against Regular Republicans (the isolationists), with Northern Democrats and Northeastern Republicans in play. And civil rights, famously, pitted Northern Democrats (the integrationists) against Southern Democrats (the segregationists), with Northeastern Republicans and Regular Republicans as the crucial pivots.

Figure 3 Factional alignments in the later New Deal era

What resulted from this political structure was “incrementalism”, a process of constant building and rebuilding of political coalitions and constant adjustment and readjustment of major public policies.Footnote 10 The latter were made and remade as the balance among the four major factions shifted, of course. But it could actually be made and remade without even much change in that underlying balance, because an initiative in one major policy domain would possess inherent implications for coalitions in the other two. One result was that all the major players needed to pursue coalition-building with an eye not just on four factions, but on the array of those four factions in three major policy domains—and on the way that these arrays would interact in response to a major policy gambit within any one.

As complicated as this might seem to the modern eye, the main players came quickly to understand the strategic logic behind it. Norms of behavior that maximized the limited but real gains that could be extracted from this logic followed inexorably. And the resulting dynamic lasted for a very long time.Footnote 11 In passing, this dynamic served as a major demonstration of the power of a newly self-conscious empirical political science, coming to fruition within this late New Deal environment.Footnote 12 At one extreme, its admirers came to view this diagnostic policy process as the genius of American politics, incremental but reliably adaptive.Footnote 13 At the other extreme, its critics complained that too little policy was being made, and that what was being made was wrong.Footnote 14 Yet neither admirers nor critics differed much about the underlying empirical reality of a complex factional politics funneled through an incremental policy-making process.

Where did the presidential candidates who populated that political world come from? The answer involves two quite different places, as befits two very different types of political party. Democratic nominees came directly out of the regular party machinery, especially the old-fashioned organized parties that still occupied the major (competitive but usually Democratic) industrial states, in consultation with a newly muscular labor movement and the burgeoning civil rights organizations.Footnote 15 As such, these nominees were effectively pre-processed for the electoral and policy realms that they would encounter. Harry Truman in 1948 was archetypal, even if he arrived by way of the vice presidency. But so was Adlai Stevenson, who owed his nomination not to the intellectuals whom he charmed but to the Chicago machine, the Illinois party, and organized allies around the country.

Republican nominees were different. Their party too had possessed organized branches in major places before the Great Depression. Afterward, however, they depended on mobilizing issue activists for a world in which their national nominees were likely recurrent losers.Footnote 16 Why, then, did the result not look like the participatory parties of the modern world, which would produce polarized nominees who catered explicitly to this sort of issue activist? Because the formal structure even of this minority party retained enough power over presidential nominations to insist on a nominee who could hope to crack the Democratic majority, as with Thomas Dewey, an apparent shoe-in in 1948, and Dwight Eisenhower, who proved to be the real thing in 1952. Diagnostically, both Dewey and Eisenhower actually defeated the favorite of Republican activists, Senator Robert Taft of Ohio, the true hero of the true believers in that far-off time.

A Parallel Vision of the Modern World?

A parallel description of the modern American political structure—the structure that either produced the Trump presidency or was contradicted by it—must begin by demarcating this modern world, ideally by way of the same general measures used to accomplish this task in the immediate postwar period. A simple and straightforward way to do this is to outline all postwar periods, the ones with a continuing structure that defines them in political terms, by the life of their diagnostic electoral outcomes. For the late New Deal era, this meant a blanketing Democratic dominance of electoral outcomes in the nation as a whole, with only one Republican Presidency and only two one-term congressional deviations. Unified partisan control of the institutions of American national government was the diagnostic and recurrent result.

That pattern was succeeded by one commonly recognized as an era of divided government.Footnote 17 In these years, from 1968 through 1988 with the sole exception of the one-term Carter “accidency”, Republicans always controlled the presidency and Democrats always controlled Congress. Split—not unified—partisan control was thus its diagnostic result. By subtraction, that leaves the years from 1992 to 2018 (and counting), as the putative modern world, if we can assign a partisan pattern that gives these years coherence as well. With hindsight, this too is remarkably easy. Though recall that the pivotal election between the late New Deal era and the era of divided government looked like a simple deviation when it first arrived.Footnote 18 Only a further generation made it clear that 1968 was instead a harbinger and not a deviation.

In the same way, the pivotal election of 1992, terminating the era of divided government and introducing the modern world, looked every bit as anomalous its first time out.Footnote 19 Yet a further twenty-five years makes it too look like part of a similarly coherent era. Partisan volatility with three marker characteristics provides the essence of this coherence: 1) a succession of two-term presidencies that alternate between the parties; 2) unified partisan control of government at the beginning of each such presidency; and 3) a return to split partisan control within each at the first plausible opportunity. A tour through the specific elections that constitute this period may help to make this coherence evident, while underlining the partisan volatility at its electoral core.Footnote 20

• At the start of Bill Clinton in 1992, there was unified partisan control of the elective institutions of American national government, in Democratic hands;

• Under Clinton, there was also split partisan control of American national government, with the presidency Democratic and Congress Republican;

• At the start of George W. Bush in 2000, there was unified partisan control of those elective institutions, but in Republican hands this time;

• Under Bush, there was also split partisan control but in the opposite direction, with the presidency Republican and Congress Democratic;

• At the start of Barack Obama in 2008, there was again unified partisan control, back in Democratic hands;

• Under Barack Obama, there was then split control in the direction opposite the Bush version, with the presidency Democratic and Congress Republican;

• And at the start of Donald Trump in 2016, there was once more unified partisan control, of a duration unknown as this is written.

On the one hand, that is a remarkably kaleidoscopic set of electoral outcomes. Direct historical analogies have to reach all the way back to the 1840s for a counterpart, a historical comparison that only emphasizes the challenge in finding some ongoing structure that can make such a pattern appear logically coherent.Footnote 21 On the other hand, the elements of just such a political structure are in truth impressively (if implicitly) consensual among modern political scientists. It is just that they resist treating those elements as a coherent whole, which leaves these political scientists free to concentrate on the idiosyncratic elements of the Clinton or the Bush or the Obama or—of course—the Trump presidency, rather than on this latter presidency as one of the small set of outcomes that are plausible within an ongoing political structure like that of the modern American world.

Again, no one is likely to confuse Clinton, Bush, Obama, or Trump as individuals, and for some purposes, it is their individual distinctions that matter. Yet a focus on the structural elements that made their presidencies possible and that shaped policy-making during their times in office is what remains central here. But what are these elements of contemporary political structure, the counterparts to those characterizing the immediate postwar years and—we think—the ones frequently saluted by contemporary political scientists who simply do not go on to integrate them into a modern whole? They are, as in the first section of this paper:

• a party balance, one more competitive than in the late New Deal era;

• an ideological polarization, light years away from the depolarized factionalism of that old world;

• a radically simplified substantive content to the policy conflicts of the modern period, as alternative policy domains collapse into one dominant dimension; and

• a process of policy-making frequently lamented as ‘gridlock punctuated by omnibus legislation.’

It is this latter lament that actually helps unify the four modern presidencies to date.

How are these key elements embodied specifically in the modern political world? Under orthodox measures of party balance, the disproportionate Democratic edge of the old world has been reduced but hardly eliminated in the modern era. Figure 4A attests to a modest erosion, accompanied by even smaller gains for Republican identifiers. Within it, figure 4B suggests that strong identifiers have been impressively stable across all these years, while weak identifiers have declined and independent identifiers multiplied, for both parties. Yet these differences, while clear, are also truly modest.Footnote 22 Moreover, the preceding era of divided government had already offered the sternest kind of warning about reading too much into change of this sort. After all, the major point of this intervening period with regard to party identification was that (with the one Carter exception), the lesser party in public preferment should always win the presidency, while the losing (albeit majority) party could expect to see its hold on Congress marginally strengthened.

Figure 4 Party Identification in the Nation as a Whole: The Coming of an Era of Partisan Volatility

Data: American National Election Studies, University of Michigan, and Stanford University. ANES Time Series Cumulative Data File (1948–2016). Ann Arbor, MI

This suggests that ideological polarization must tell a much larger share of the changing structural story of modern American politics, as indeed it does, though its traditional measure still highlights only one part of the change while actually masking the other. The highlighted part is the factional story, or rather, the shriveling of the dissident factions. Seen one way, those previously dissident party factions have indeed been in serious decline. Seen the other way, the two leading factions, Northern Democrats and Regular Republicans, have become correspondingly and increasingly dominant. Such shifts automatically increased ideological polarization nationwide, by undermining the depolarization that once followed from a sharply factionalized politics. Yet this still masks what has happened to both the dominant and the secondary factions in both parties.

For in fact, as those parties have become more ideologically homogenous, they have simultaneously pulled farther apart in their ideological centers, leftward for the Democrats and rightward for the Republicans.Footnote 23 This is the classical meaning of “partisan polarization”, and here, its canonical measure (reproduced in figure 6) is especially good at telling the story. Focusing once more on Congress, that measure attends both to the cross-pressured members, those who were closer to the mid-point of the other party than to their own, and to the stereotypically moderate, who were merely closer to the center of Congress than to the center of their own party.Footnote 24 Figure 6 attests to the decimation of these incipiently bipartisan members after 1992, the beginning of our modern world. Though even that display risks understating the degree of change in ideological polarization because this onward march of partisan separation was now being applied to the changing balance of party factions analyzed at figure 5.

Figure 5 Factional Composition of the Two Parties in the House: The Late New Deal Era and the Era of Partisan Volatility

Data: Lewis, Jeffrey B., Keith Poole, Howard Rosenthal, Adam Boche, Aaron Rudkin, and Luke Sonnet (2017). Voteview: Congressional Roll-Call Votes Database. https://voteview.com/

Figure 6 Partisan Polarization among Public Officials

Fleisher & Bond Reference Fleisher and Bond2004, The Shrinking Middle in the US Congress, p. 437

What the fortunes of these two cohorts imply, jointly and inescapably, is that the mainstream of both parties is now nearly bereft of cross-pressured or even moderate congresspersons. Yet that is still not the whole structural story, for a further, major, knock-on implication of this extensive partisan polarization is that it is stiff enough to annihilate the ideological complexity that characterized the old world, whereby different policy domains—social welfare versus foreign affairs versus civil rights—actually placed the four main factions in differing ideological alignments. Now, in a modern world where there are few cross-pressured or moderate congresspersons surviving, the sitting members obviously stand in the same general relationship to each other on all major policy dimensions.Footnote 25 Ideological polarization has in effect wiped out the differential effects from different substantive contents. Instead, there is just one underlying (and overwhelming) ideological continuum among partisan office-holders: Democrats sharply to the left and Republicans sharply to the right.

Where did this highly—and intransigently—polarized world come from? Two major developments were central to its appearance, central both to breaking up an established order and to producing the modern world of American politics. The first of these was the disappearance of the one-party South, a development much-loved by analysts on its own terms, but with a sting in the tail for those concerned with the issue of ideological polarization. The second was the concentrated (and successful) assault on old-fashioned party rules and party organizations in the name of a much more open and participatory politics. Like the first major contribution, this too came with widely saluted justifications, coupled with the side-cost of greater ideological polarization. Needless to say, in the American South, where these two key developments interacted, their effects were at a maximum.

The disappearance of the “solid” one-party South, and with it the disappearance of a long-established three-party system for the nation as a whole—Northern Democrats, Southern Democrats, and National Republicans—was by itself a sea change in the structure of American politics. It would be a rare scholar who dissented from that particular generalization, and the scholarly debate instead focused on what had driven this change: racial desegregation, economic development, or some specified mix of the two.Footnote 26 Yet at 30% of the nation as a whole, a one-party South had been a huge depolarizing influence on American politics. Since nearly everyone in the region was once in the same party, 30% of the nation was effectively unipolar. When Southern politics came into alignment with national politics, now splitting the South ideologically in the form already characterizing the other 70% of the nation, the country as a whole became invariably and substantially more polarized.

Inside the region, both main aspects of this development were more or less explicitly polarizing, though hindsight makes this look more inevitable than it did in its time. A huge new increment of black Democrats helped guarantee that Southern Democrats would thereafter be national Democrats. Had national Democrats evolved differently, the preferences of this reconstituted Southern increment might have reinforced economic liberalism coupled with cultural moderation, pushing against the tendency for partisan polarization to reduce ideological heterogeneity. Instead, while there were to be fewer Southern Democrats in Congress as a whole, those who surfaced or survived were largely indistinguishable from their Northern colleagues. Across the aisle, there was an equally striking change, in the form of a newly serious geographic faction, namely Southern Republicans. Yet these new Southern Republicans, rather than emerging as a more moderate strand within their own party, entered politics in full—even exaggerated—conformity with the polarized ideological alignment characterizing its non-Southern components.Footnote 27

That was still a regional contribution, however portentous. Yet it occurred in tandem with a second, great, fully national phenomenon, the coming of participatory politics. Symbolized most strikingly by the implosion of the Democratic National Convention of 1968 over issues of participation in internal party affairs, the resulting party reforms were only the most focused part of a much larger movement in the late 1960s and 1970s.Footnote 28 This movement for participatory reform swept away the old institutional framework for delegate selection and presidential nominations. Yet it reached widely and deeply into the conduct of party business more generally. Even then, party affairs were not the limit of its impact, for the reform drive went on to reach the institutions of American national government themselves, most especially with regard to the internal operations of Congress and the internal procedures of the federal bureaucracy.Footnote 29

Analysts had long understood that different party structures were underpinned by different incentive systems—pitting material against purposive incentives, as well as the social groups that could best be mobilized by one versus the other.Footnote 30 But when the focus moves out from party reform to ideological polarization, the point is instead that different incentives also pitted an older preference for compromising policy issues to secure programmatic outcomes against a newer preference for uncompromised policy preferences as a means of stimulating political participation. Said more concretely, different incentives plus different structures pitted the old formal organizations of long-serving party officials against the new social networks of issue activists.Footnote 31 And by the 1990s, the participatory side of this equation—purposive incentives, volunteer structures, and activist networks—was widely triumphant. So, in turn, was a set of new issues and of more extreme ideological positions on them, since this was the combination most conducive to generating the autonomous activism necessary to make such a party system function.

How Does the Trump Candidacy Fit?

So what does American politics look like in this light? At a minimum, there is no reason to believe that the modern era is different from any of the preceding periods in the sense that political actors must seek public office and then public policy within the structural constraints of their own (and not some other) period. For the contemporary period, despite a veritable kaleidoscope of partisan outcomes, these structural constraints are defined by four simple propositions:

• The balance between the two parties within the general public is closer than in the immediate postwar years, or for that matter in the era of divided government. This is true even when party identification is the measure. It is truer—and more realistic—when voting behavior is instead the focus. Figure 7 captures this succinctly.Footnote 32

• The political parties as organizations are just as clearly farther apart than in the late New Deal or the era of divided government. It would have been theoretically possible for the two to move closer together as they became more closely balanced. That is not what happened. Indeed, this effect was strong enough to spread downward to other levels of a federal system and outward to other national institutions besides the legislature.Footnote 33

• The electoral result has been ironic. Voters have an easier time than ever choosing between parties that are ideologically distant. Yet this comes at the price of recurrent public disappointment, as winners prove more committed to the programs of their (non-overlapping) political parties than to the preferences of a voting public, the bulk of which is always to the right of a winning Democrat or the left of a winning Republican.

• Though if this public is constantly disappointed, it also has a quick and easy means of revenge. Or at least, it is easier than ever to respond to disappointment by shifting partisan control of governmental institutions, any or all of them. A close party balance requires relatively little change among these voters—a small shift at the polls, just differential turnout—in order to change partisan control and produce the electoral kaleidoscope that characterizes the period.

Figure 7 Party Balance as Reflected in Voting Behavior: The Presidency, the Senate, and the House Combined

Black bars reflect Republican edge; white bars show Democratic edge; dotted gray bars show an edge of less than 1% either way.

Frances E. Lee, “American Politics is More Competitive Than Ever, and That is Making Partisanship Worse”, Chapter 11 in Daniel J. Hopkins and John Sides, eds., Political Polarization in American Politics (New York: Bloomsbury, 2015), Figure 4–3

Enter Donald Trump, descending the escalator at Trump Tower in New York and offering himself as a candidate for president of the United States.Footnote 34 But where does this anomalous politician—first in the form of the Trump candidacy, then in the form of a Trump presidency—fit into the political structure of the modern United States? From the start, pundits had a terrible time with the Trump candidacy, initially failing to treat it seriously, then doing a collective version of “this can’t be happening”.Footnote 35 Perhaps that is why nearly no one treated the candidacy as one logical product of the continuing structure of modern American politics—not the most common product, to be sure, and one that offered idiosyncrasies galore—but a fairly straightforward outcome if one reasoned back from the four propositions that collectively define the modern political era in the United States.

Consider. In a closely balanced but sharply polarized world, the expected outcomes of presidential nominating politics are a Democratic nominee who is stiffly liberal in ideological terms and programmatically consistent with that ideological orientation, against a Republican nominee who is stiffly conservative in ideological terms and programmatically consistent with that ideological orientation too. In truth, the modern world just gets better and better at producing such candidacies and confirming such nominees. But what if the majority of general election voters reliably resides to the right of one of these nominees and to the left of the other?

In the abstract, such a world could generate an actual centrist party. In practice, the barriers to this particular adaptation are huge.Footnote 36 Institutionally, they include ballot access rules, fund-raising provisions, and existing organizational infrastructure. Behaviorally, they feature the existing ideological activists, who, if they are in some sense the proximate cause of the disjuncture, have proven remarkably adept at amalgamating extreme positions while freezing out incipient contenders who do not buy into the result.Footnote 37 So the obvious—dare we say logical?—alternative to potential nominees who can please their active parties but not the general public comes down to some variant of centrist contender who secured the nomination of one or the other major party.

But centrist in what sense? Here, there are two available options. The leading theoretical alternative would be a partisan aspirant who fell between the two major-party nominees on the grand issues of modern politics, being more moderate than either on both economic and cultural concerns. This, too, simply has not happened, and if the remaining median-voter theorists puzzle abstractly over that cruel concrete fact, behavioral analysts have actually gone a long way toward explaining it. A bit of this puzzle is artifactual. Opinion analysts all too frequently assign those who answer “don’t know”, “not sure”, or “decline to state” to the middle of a distribution, rather than exiling them from the analysis and thereby losing precious N. Less easy to handle are those individuals who offer a moderate answer as a socially acceptable means to say either “I don’t care” or “I hate politics”.

Yet the larger explanation for this lack of an institutionalized centrist alternative is richly developed in theoretical terms and inherent to the actual distribution of policy opinions within the American public. Over and over, analysts find that the general public is not polarized in its policy preferences, which do indeed constitute the classic bell curve. In fact, many preferences have actually become more consensual, not more polarized, over time.Footnote 38 What makes this picture nevertheless consistent with increased partisan polarization is that the parties have increasingly drawn identifiers who lean liberal (for the Democrats) or conservative (for the Republicans), so that neither party is close to being a bell curve at the center of American society. In such a world, the theoretically simplest response to close partisan balance coupled with strong ideological polarization—in the form of a uniformly moderate centrist alternative—is actually very hard to generate.

On the other hand, a centrist option for such a world could in principle be constructed quite differently. To win—and here we begin to close in on the Trump candidacy—such candidates could appeal to those leaning Democratic on one major policy domain, like economic values, while simultaneously leaning Republican on another major domain, say cultural values, or of course vice versa.Footnote 39 This is in effect the main alternative way to speak to the vast American middle, a middle that is neither strongly and consistently liberal nor strongly and consistently conservative. Moreover, this route was under consideration by other incipient candidates well before Donald Trump brought it to life in his own personally idiosyncratic fashion.

The longest-running of these self-consciously middle-of-the-road proto-candidacies, and in that sense the longest-running nomination tease, belongs to Michael Rubens Bloomberg.Footnote 40 Bloomberg, entrepreneur and central figure in the eponymous Bloomberg LP, a finance, media, and software conglomerate, switched from Democrat to Republican when he first ran successfully for mayor of New York City in 2001. Re-elected as a Republican in 2005, he changed his party registration to Independent, campaigned for an amendment to term limits, and then ran successfully for a third term in 2009 as an Independent, albeit on the Republican line.

In 2008, he resisted the entreaties of a “Draft Bloomberg” movement but announced that he would endorse a non-partisan alternative to the Democratic and Republican nominees for president, arguing, despite his own obvious reticence, that neither party had the comprehensive answers necessary to solve American problems.Footnote 41 No such independent option emerged. The “Draft Bloomberg” movement surfaced again in 2012 but was denied once more by its chosen candidate, who this time endorsed the incumbent president, Barack Obama. Finally in 2016, the elusive candidate mounted a conscious exploratory operation of his own, ostensibly motivated by the nightmare scenario of a fall campaign featuring Donald Trump versus Bernie Sanders. While he was reported to be reinforced by the judgment that he himself was best able to appeal to moderate and centrist voters, Bloomberg ultimately disbanded the exploratory effort and endorsed Hillary Clinton.Footnote 42

Without an actual nominating campaign, we cannot use policy promises from this three-contest scenario to classify the incipient candidate, though Bloomberg does stand as one plausible incarnation of an aspiringly centrist policy mix, being, in his case, an economic conservative but a cultural liberal. The closest pre-Trump embodiment of the opposite mix, combining economic reform with cultural conservatism, was probably Charles Elson “Buddy” Roemer III, Democratic member of the House of Representatives from Louisiana from 1981–1988, Democratic Governor of Louisiana from 1988–1992, unsuccessful Republican candidate for re-election in 1992, and occasional Republican candidate for various other offices thereafter—until a quixotic run for president in 2012, first as a Republican and then as an Independent.Footnote 43

Unlike Bloomberg, Roemer had an actual policy record, always featuring campaign finance reform and vigorous attacks on “the interests”, coupled with tough stands on street crime and welfare fraud, though the balance differed with the office being sought and the stage of his own career. In 2012, he announced a run for the Republican nomination for president, a gambit hampered from the start by aggressive attacks on fellow Republicans as “bought and paid for” and by his own inability to raise funds. He shifted briefly to an attempt at the presidential nomination of the Reform Party, the skeletal remains of the Ross Perot campaigns. Roemer moved on quickly, however, to an effort to get the nomination of a new citizen organization, “Americans Elect,” which promised an open national primary where all members could run or nominate and where a sequence of three such rounds would settle the nomination. Among a huge array of initial possibilities, Roemer actually came first in the membership survey of favorability. Yet even his showing never rose above derisory, and the organization eventually gave up on any actual primary.Footnote 44

Roemer’s announcement in 2011, on his way to this peripatetic effort, that he appreciated the values of both the Occupy Movement and the Tea PartyFootnote 45 is perhaps as extreme an example of mixing ideological positions as any candidacy seeking to escape a polarized two-party politics—until President Trump put together a different but equally idiosyncratic mix in 2016. Donald John Trump was originally a real estate developer and hotel magnate who became a reality TV star in more recent years. The combination gave him a ready public audience for occasional political utterances, and he expressed at least a curiosity about running for president in 1988, 2000, 2004, and 2012, as well as for governor of New York in 2006 and 2014.Footnote 46 While he never actively pursued any of these, he did file an exploratory committee to allow him to run for the presidential nomination of the Reform Party in 2000. Along the way, he, like Bloomberg and Roemer, switched party affiliations intermittently, from Democratic to Reform to Democratic and then to Republican in 2009. Footnote 47

Trump did finally run for (and win) both the Republican nomination and the presidency in 2016, so that unlike Bloomberg or Roemer, he had far more actual programmatic promises to locate him with regard to the two major parties. These offered a truly eclectic mix of policy preferences.Footnote 48 Trump ran to the right of his own party, the Republicans, on immigration and crime. He conformed to its orthodox positions on abortion (where he had once been pro-choice), on taxation, and on governmental spending. He veered well left of his party when he promised sweeping infrastructure investment and broad healthcare reform without cuts to the major insurance programs of Medicare and Social Security. And he travelled all the way over to the labor part of the Democratic coalition on foreign trade and protectionism.

How Does the Trump Presidency Fit?

That combination was sufficient to disturb (and in some cases repel) party officials and public office-holders from his own party on the way to the nomination.Footnote 49 Yet it was obviously not sufficient to derail his drive for the presidency, and various individual pieces of his campaign program were afterward judged to have been effective in adding specific elements to his voting constituency.Footnote 50 So Donald John Trump differed from most other ideologically unorthodox candidates, and indeed from all but forty-four other human beings, not just by standing for election but by actually becoming President of the United States. As a result, a version of the same question that could be asked about his candidacy should be asked about his presidency to date: how does the Trump presidency fit into the ongoing structure of American politics?

Journalistic complaints to the contrary, the political structure of the modern American world does possess a clear process of policy-making, with an equally clear patterning to the result. So setting that out is the first task of this analytic section. Within this composite process, President Trump has brought numerous personal idiosyncrasies to his conduct of the office, and these may seem more striking than those of his three immediate predecessors, not just in possessing a specific career in reality TV but also because he was generally much farther from politics as a profession when he secured the office. But does the combination—an ongoing structure, an idiosyncratic personality—suggest a nascent new era in American politics, or does it instead embody patterns of policy-making common to presidencies from 1992 through 2018?

The story of policy-making in an era of close party balance and strong partisan polarization, one with kaleidoscopic shifts in partisan control of the major institutions of American national government, can—despite its surface complexity—again be easily summarized. Though let us begin this time by considering the absent elements in this process, the ones that defined national policy-making in the preceding postwar years. Among these, the major geographic regions that once demanded a constantly incremental process of policy-making are simply gone, with the result that any factional successors no longer line up in different ideological positions on different major issues.

So are the giant cross-partisan and cross-institutional coalitions that followed inexorably from a static pattern of split partisan control during the period of divided government. In this second postwar period, policy-making was different from the earlier postwar years, thanks to the absence of those great (and incremental) regional factions. Yet increasingly polarized parties had to face the fact that they might never be able to govern on their own, even if they increasingly disliked the opposition. Democrats would always hold Congress. Republicans would always gain the Presidency. As a result, both parties still had powerful incentives to build the giant coalitions characteristic of this second postwar period, thereby dealing themselves into all major policy outcomes.

In the modern period, however, in the absence of factional building-blocks or facilitative election outcomes, there are just two great polarized parties facing each other without mediating groups or mediating incentives. What follows, logically and ineluctably, are long periods of gridlock and stasis, broken by sharp spikes of policy-making. Despite some confusing statements and contradictory signals from the man himself, the actual legislative record of the Trump administration has served well at putting concrete policy examples into this abstract model of the policy-making process in our time.

Normal legislative politicking of the modern sort cannot generate the constant policy increments of the earliest postwar years. There are no sizable blocs left within either party that can regularly be attracted to the other on an ad hoc basis. Normal electoral politicking of the modern sort will likewise not generate the consistent record of grand coalitions that occurred during the era of divided government. Electoral incentives now run in the opposite direction, where the most attractive strategy is often to prevent the other party from legislating until the next turn in the electoral kaleidoscope. Accordingly, gridlock can indeed be used to describe the “steady state” for modern American politics.

Yet the term should be used with care. For despite generalized laments about its blanketing character, policy continues to get made. Moreover, it may not even be made on a more limited scale than it was in the past. After all, George W. Bush did rebuild the national security apparatus of the United States in its entirety, surely the biggest such rebuilding since creation of the institutional machinery for pursuing the Cold War in the immediate postwar years.Footnote 51 And Barack Obama reconstructed an entire healthcare regime—one-sixth of the U.S. economy—surely the biggest such reconstruction since Medicare and Medicaid under Lyndon Johnson.Footnote 52 To cap off these particular examples, an aggregate analysis of major policy initiatives across the entire postwar period likewise does not make the modern world look comparatively laggard.Footnote 53

Table 1 Policy productivity by political era

Source: Mayhew Reference Mayhew2005, 51-73 and 207-213, as updated on the author’s website

On the other hand, this policy does get made differently, through a recurrent process of policy-making unlike those characterizing the immediate postwar years or the successor period of divided government. Its dominant pattern and signature product was actually isolated early in the modern period, even before the larger political structure of the period had itself been recognized. This signature product was “omnibus legislation”, whereby extended gridlock is unpredictably but unfailingly interrupted by major spikes of policy-making, driven by the build-up of pressures for governmental action.Footnote 54 The fact that this modern form of legislative production tends to be both large and temporally compressed discourages analysts from thinking about it as an integral part of an overall process, but so it is.

There are three recurrent drivers to this. Sometimes these spikes are the result of a consensual crisis, as with 9/11 for George W. Bush or the Great Recession for Barack Obama. Other times spikes can instead be the result of an unavoidable reauthorization, as with raising the debt ceiling or producing a new budget to fund an inevitably changing government. Still other times they can be the simple product of a collective build-up of policy wishes so intense as to precipitate what is politely recognized as omnibus legislation—really a giant log-roll pulling all these pent-up demands into one legislative spasm. Though note that the appearance of any one of these inescapable stimuli ordinarily provides what is known among the major players as a legislative “Christmas tree”, the opportunity to link other ongoing policy demands to the underlying deadline.

The three major policy initiatives of the Trump administration to date are in this sense archetypal examples of these policy spikes. For the moment, however, in a world with the underlying political structure of our time, the prior point is that this overall story of policy-making has been essentially the same for every one of the four modern presidents. A few leading examples may help to underline the commonality to this diagnostic pattern:

• For Bill Clinton, the new pattern was introduced with the first major bill of the Clinton presidency, his Omnibus Deficit Reduction Act of 1993, passing the House by a vote of 218-216, which masked a partisan split of 218-41 among Democrats and a theretofore remarkable division of 0-175 among Republicans.

• For George W. Bush, the pattern arrived with his opening tax cuts of 2001, to be confirmed in his tax cuts of 2003, passing the House by a vote of 231-200, but with Republicans going 224-1 and Democrats splitting opposite at 7-199.

• For Barack Obama, his opening stimulus program of 2009 absolutely lit up this diagnostic background, with a final House tally of 244-188, broken down as 244-11 among Democrats but 0-177 among Republicans.

In any case, in less than the full run of a single Congress, Donald Trump has actually managed to generate a major example of each of the generic forms of policy spike that respond to this ongoing background in the modern era, though only two of them were a success while the third was a dramatic failure. The first major policy win came on tax reform.Footnote 55 Once more, the House passed legislation, 224-201, covering a Republican split of 224-12 and a Democratic split of 0-189. And this time, the Senate passed legislation as well, however narrowly, with a tally of 51-48, covering a perfect Republican split of 51-0 and a perfect Democratic counterpart of 0-48. That was an obvious continuity stretching all the way back to the first major legislative win of the first-term Clinton presidency.

While most commentators failed even to connect the pure partisan vote that passed this tax reform package to an ongoing pattern inaugurated by Bill Clinton and reinforced by George Bush and Barack Obama, they did at least acknowledge its party-line character. A student of omnibus legislation should also have noticed, however, that Congress, working on tax reform almost up to Christmas itself, once again converted a major policy initiative into the true national Christmas tree:

• The tax proposals themselves were comprehensive and diverse, including provisions affecting individual tax rates, state and local tax deductions, and the child tax credit.

• Yet these served additionally as a framework on which Congress could hang such further, disparate, but major “ornaments” as educational incentives, repeal of the individual insurance mandate under Obamacare, and permission to drill for gas and oil in the the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.Footnote 56

• Moreover, it was these ornamental provisions, not the central substance of the legislation, that held a congressional Republican majority together behind the total package.

That still left an array of pending items with the potential to create a further policy spike in the new year: an extended operating budget to prevent governmental shut-down, reauthorization of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), a substitute for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, disaster aid for the victims of recent hurricanes and wildfires, along with funding for an announced attack on the opioid epidemic.Footnote 57 One or another item on this list might still fall by the wayside, despite practical (and sometimes statutory) deadlines plus real constituency support; DACA would be the one that met this fate. Yet all were obvious grist for another major policy spike, being powerfully unlikely to be pursued in a vacuum, that is, in disregard of the other items on the list. And this one would exemplify a second generic type of spike in the modern world, the one impelled by a giant log-roll.

The centerpiece was to be a new, two-year operating budget for the federal government, a project previously left for dead in the face of the Trumpian incarnation of the modern pattern of American policy-making. Yet 2018 instead brought one largely shared bipartisan driver toward a new budget, in the form of a succession of governmental shutdowns, risks of governmental shutdowns, and threats of governmental shutdowns, where the major players could no longer be sure who the public would blame for the next such (mis)adventure.Footnote 58 The main further driver was then actually—and ironically—the complete polarization of policy preferences for any new budget. Republicans overwhelmingly wanted to escape the spending strictures that they themselves had extracted from then-President Obama in 2011, so that they could do a major increase in military spending. While Democrats, never enthusiastic about fiscal constraints, were even more desirous of escaping their strictures, in the name of a major increase in domestic spending.

The resulting one-point-three-trillion-dollar spending bill was excoriated from both ends of the ideological spectrum. Nancy Pelosi, House Minority Leader, held the floor for an entire day to condemn it for failing to include reform or at least reauthorization of DACA. The House Freedom Caucus, the last organized support for the Obama-era concern with the fiscal impact of federal budgets, denounced the agreement and provided the largest single bloc of opposing votes.Footnote 59 Still, the bill passed even the House comfortably, 256-167, losing the most liberal Democrats on the left and the most conservative Republicans on the right while securing majorities of both parties. With the same general profile, the Senate was anticlimactic, raising only the question of whether one or another Senator would exercise their personal prerogative to delay it for a few further days.

In the process, yet unsurprisingly in the modern policy world—imagine tacking solar panels onto the Civil Rights Act of 1964 or opioid addiction onto the Environmental Policy Act of 1969—a set of major policy concerns were variously addressed, managed, or driven off into the future. The federal debt ceiling was raised, exiling that always-contentious matter until well after the November elections; the two-year scope of this budgetary log-roll went on to guarantee that no one would have to endure such contentious budgetary politics until comfortably into the successor Congress; the possibility of a governmental shutdown (or even the realistic threat of same) was likewise shipped off into the future; a second substantial contribution to CHIP, a program quite popular at the state level, was thrown in for good measure; and funding for those recent hurricane and tornado disasters was at last provided on a major scale.

Modern presidents often try consciously to manipulate this modern pattern of legislative production in one further way, by capitalizing on the sudden appearance of unified partisan control at the beginnings of their administration. Polarized partisan divisions remain as sharp as ever, but for a brief stretch they appear as if they might allow legislating anyway. For Presidents Clinton and Obama, these stretches were very brief, a single term of unified government, followed by the recapture of at least one house of Congress by the other party for the next six years. For President Bush, the policy earthquake that was 9/11 stalled off the prospect of a first-term crash, though it did forcibly redirect policy-making (toward national security) in the process. And for President Trump, their lineal successor, the same perceived need to capitalize on this opportunity was a driving force behind his opening healthcare initiative.

This time, however, the initiative was a failure; in the end the necessary generalized pressures for change were simply not there.Footnote 60 Too much of the congressional Republican Party was committed to the complete repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA, commonly called Obamacare). Too much of the congressional Democratic Party saw no need to adjust anything. The handful of Republicans who preferred reform but not repeal, most especially in the Senate, found few allies in their own party. And far too few Democrats were inclined to invest in the minutiae of reform.

The House still managed to pass legislation in the conventional modern form, 217-213, covering a Republican split of 217-20 and a Democratic split of 0-193. Yet the Senate fell just short, with a vote of 48-51 covering a Republican split of 48-3 and a Democratic split of 0-48. An aroused general public might have made a difference—it might have given this initiative a chance to be the opening policy spike of the new administration—but if that public had not been powerfully aroused by the original need for the ACA, it was even less aroused by the alleged need to undo it.

How Far Should These Analogies Go?

Donald Trump did not create the contemporary structure of American politics. Indeed, with a prior career outside conventional politics, he did not even shape what he encountered, though nothing in that history guarantees that he will not make just such a contribution going forward. In the meantime, he was one product of an established electoral structure, while he inherited an established process of policy-making, one on characteristic display in his three diagnostic struggles over healthcare, tax reform, and budgeting. In the aftermath of those struggles, there is little reason to expect domestic politics to generate another major policy spike—external shocks are always quite another matter—until after the midterm elections in November of 2018. So we can in principle close, for good or ill, with the next sure structural element in the fortunes of his administration, namely his first mid-term.

Non-stop prognostication in the coverage of modern American politics means that various professional analysts have been attempting to divine the 2018 outcome for almost as long as this president has been in office. So a closing interpretive effort should confine itself to looking backward at the pattern of election outcomes in this modern world, applying any such pattern to the ongoing structure of modern politics. In effect, this is a search for analogies and their limits, specifying possibilities but eschewing pointed predictions. In that light, and to repeat, the electoral outcomes accompanying a modern American political structure can be simply summarized.

Each of the modern presidencies to date has been a two-term affair, though their operations have been heavily colored by the loss of at least one house of Congress in subsequent elections. For the two Democrats, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, this loss was rapid: one congressional term of unified partisan control was all they got, so the institutionalized public discontent of our current political world caught them at its first opportunity. For the first of two Republicans, George W. Bush, that loss was pushed into the second term, though it is hard to escape the hypothesis that electoral delay was greatly facilitated by 9/11 and thus by a perceived need on the part of the general public to rally behind a national response.

A straightforward extrapolation from this modern world to 2018 would be discouraging for the Trump White House. Or at least, there does not appear to be anything on the scale of 9/11 to provide respite from the inexorable implication of a relentless modern analogy: the loss of partisan majorities in one, the other, or both congressional houses. The specifics required to realize this analogy remain demanding. While a small net partisan loss would be sufficient to shift control of the Senate, even this small loss would have to be realized in a contest where there are 24 Democratic seats (plus two Independents who caucus with them) up for election but only eight Republican counterparts. Conversely, while a much larger shift would be required to change control of the House, currently 247 Republicans over 188 Democrats, a shift on that scale was in fact accomplished in all three counterpart elections, 1994, 2006, and 2010.

Though in the end, this analogical outcome may have a silver lining for the President himself. Or at least, the early loss of unified partisan control had no serious effect on the re-election of Clinton and Obama. And their successor, Donald Trump, is in some ways the best prepared of the four modern presidents to deal with an analogous outcome, in that his mix of policy promises on the way to the White House contained enough contrary propositions to allow him to resurrect some while jettisoning others. What will remain true of a Trump presidency after 2018, regardless of the election outcome, is an underlying picture of modern American political structure: close party balance, galloping partisan polarization, an easy public facility for registering a change of mind, yet reliable disappointment with the resulting partisan shifts. These are not the details of legislative politicking. But they are its recurrent—shaping—influences.

To summarize, increasing partisan polarization created both programmatic space and a potential constituency for off-diagonal candidates, those who do not neatly fit into the issue alignments characterizing activsts in the modern American party system. Donald Trump is not the first, nor will he likely be the last, to attempt to pick and choose from the normal arsenals of both parties in order to appeal to voters who are neither doctrinaire liberals nor doctrinaire conservatives. For Trump as for all three of his immediate predecessors, however, once he had secured the nomination, a different but equally powerful set of macro-patterns kicked in: close party balance, reliable public disappointment with any result, ease of changing partisan control in response. The resulting process of policy-making, first recognized in the 1990s and increasingly familiar since then, brought imperatives all its own, and the Trump presidency—as exemplified in healthcare, taxation, and budgeting—could not escape its version of the same continuing strictures from that process.

Put differently and to return to the dominant analogy of our time, if one had asked the authors before the 2014 mid-term about who would win the presidency in 2016, the answer would have been the Republican nominee. The modern electoral pattern and its structural underpinnings would have pointed toward that general outcome. Donald Trump, as unusual a candidate as he was and as much as the Repbulican establishment appeared to dislike him, did not break the pattern. Russian meddling, Democratic infighting, FBI decisions, populist rhetoric, the ubiquity of the twitter-sphere—and on and on—put idiosyncratic details into an overarching result. One of these, or many other details of the time, might yet prove important in historical hindsight. Yet in the end macro-patterns and macro-structures put Donald Trump within reach of the presidency and then constrained him as president, despite his best idiosyncatic intentions.