Governments around the world increasingly militarize law enforcement and launch military campaigns to fight organized criminal groups (OCGs) and to confront major spikes of criminal violence. In countries such as Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, and the Philippines, national governments have declared Wars on Drugs and deployed military forces to fight drug cartels or street gangs and to reclaim subnational territorial control in towns, villages, and marginalized urban neighborhoods. Extensive research shows that the deployment of the armed forces or militarized police forces often fails to reduce crime (Blair and Weintraub Reference Blair and Weintraub2023) and instead stimulates turf wars, resulting in major spirals of homicidal violence and gross human rights violations (Lessing Reference Lessing2017; Flores-Macías Reference Flores-Macías2018; Magaloni and Rodríguez Reference Magaloni and Rodríguez2020; Flores-Macías and Zarkin Reference Flores-Macías and Zarkin2023). But we know less about the consequences of these wars on a key pillar of democracy: press freedom.

In this article we focus on the multiple waves of attacks against journalists in Mexico that took place after the federal government launched a War on Drugs and deployed 45,000 troops in staggered military campaigns to fight drug cartels in the country’s most conflictive regions. While in the twelve years prior to the War on Drugs on average 3.3 journalists were killed per year, during the twelve years when the army was deployed to fight cartels on average 10.2 press workers were murdered annually. This threefold increase in lethal attacks against the local press has turned Mexico into the world’s deadliest country for journalism. Between 2000 and 2019 a staggering number of 156 journalists were killed in Mexico, and in 2019 the country accounted for nearly 25% of the world’s murdered journalists (CPJ 2020). Crucially, nine out of every ten journalists killed are town- and city-level journalists who investigate events in their places of residence. International correspondents and national-level journalists are rarely murdered.

Did the War on Drugs trigger the waves of assassinations of local journalists in Mexico? To address this question, we broaden our lens and focus on criminal wars—the militarized conflicts that take place when states militarily attack drug cartels and other OCGs or when cartels use their private militias to fight rival criminal groups for control over illicit economies and subnational territories (Lessing Reference Lessing2017). Criminal wars involve multiple actors and conflicts: 1) state-cartel military conflicts (e.g., the War on Drugs); 2) inter-cartel armed conflicts (turf wars); and 3) struggles for de facto control of local economies, societies, and governments, and for the reconfiguration of local orders—a phenomenon known as criminal governance (Arias Reference Arias2017). In Mexico, five drug cartels and their private militias went to war in the 1990s (Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2020), but inter-cartel conflicts grew exponentially after the Mexican federal government declared war on the cartels in 2006, leading to the fragmentation of the criminal underworld into over 450 OCGs and to the proliferation of localized turf wars and power struggles across the country (ICG 2022). Twelve years after the onset of the War on Drugs and the multiple conflicts it unleashed, criminal wars in Mexico had resulted in over 150,000 battle deaths and over 60,000 disappearances.

The waves of attacks against local journalists in Mexico are puzzling for two reasons. First, it is unclear why state and criminal actors fighting deadly military conflicts would divert precious resources to selectively murder journalists who are not a party in these conflicts. Second, it is surprising why perpetrators would overwhelmingly attack town- and city-level journalists, whose resources to influence policymaking and spread news are much more limited than those of national journalists. In a context marked by a 98% impunity rate (Article-19 2024), in which practically all assassinations of journalists remain unpunished, it is urgent to understand why attacks are predominantly aimed at silencing local journalism.

Our central argument is that risks of assassination in Mexico grow exponentially for local journalists who reside in and report from states, cities, and towns where national governments deploy the armed forces to fight cartels, particularly when military interventions and state-cartel wars unleash major inter-cartel armed conflicts and power struggles for the reconfiguration of local orders. In these conflicts, local journalists are vulnerable to lethal attacks because of what they do—they are professionals reporting and investigating criminal wars in their places of residence. Drawing on their deep local networks and journalistic investigations, they produce fine-grained information about battlefield dynamics of state-cartel and inter-cartel wars and about the fierce struggles for the control over subnational territories, illicit economies, and local social orders. Their work can expose unwanted information that upsets the balance of power in the criminal underworld and jeopardizes criminal and political actors’ access to extraordinary illicit rents and de facto power. Criminal-political actors will possibly seek to mitigate the risks of unwanted information through lethal violence, punishing local journalists for past publications, or preventing future compromising reports. But local journalists are also at risk because of who they are: their high-profile voice and legitimacy in their towns and cities enable them to challenge de facto criminal-political controls and raise the transaction costs of criminal governance.

In building our argument, we follow a new paradigm of “criminal politics” (Arias Reference Arias2017; Barnes Reference Barnes2017; Durán-Martínez Reference Durán-Martínez2018; Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2020) that sees organized crime as a field of state-criminal networks in which criminal groups collude with state security forces and politicians to operate a wide variety of illicit economies. Because these illicit industries are global chains of local operations, subnational elected and security officials play a major role in the development of the state-criminal networks that control the criminal underworld—the gray zone of criminality (Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2020). When states deploy the military to fight cartels or OCGs and trigger multiple armed conflicts and power struggles, criminal lords and their allies in subnational elected and security offices are at the forefront of these localized criminal wars.

Our focus on local journalism builds on new research that has shifted scholarly attention away from international correspondents and national journalists to local press workers and subnational power and criminal struggles (Hughes and Márquez Ramírez Reference Hughes and Ramírez2018; Carey and Gohdes Reference Carey and Gohdes2021; Hughes and Vorobyeva Reference Hughes and Vorobyeva2021; Salazar Reference Salazar2023). We diverge, however, from this new literature in understanding crime and politics as interrelated rather than independent spheres. Unlike cross-national studies suggesting that subnational authoritarian elites in national democracies murder journalists to prevent the publication of unwanted information about corruption and illicit activities (Carey and Gohdes Reference Carey and Gohdes2021; Hughes and Vorobyeva Reference Hughes and Vorobyeva2021) and unlike important studies of drug violence claiming that drug cartels murder journalists to govern information flows amid turf wars (Holland and Ríos Reference Holland and Ríos2017), in this article we bring the state back in and predict that risks of assassination for local journalists in Mexico heighten when they report on the multiple localized conflicts that the federal government’s War on Drugs unleashed. In line with the “criminal politics” paradigm, we expect subnational elected and military and security officials, in collusion with criminal groups, to play a prominent role in the joint production of violence against the press.

To test our argument, we follow a mixed-method approach by which we first use statistical models to evaluate the effects of the military intervention and the multiple localized conflicts it unleashed on the risks of assassination of journalists. These statistical models help us explain when and where attacks are more likely to take place. To assess why reporting about these conflicts heightened risks of lethal attacks for local journalists and identify the likely perpetrators and their motivations, we use focus groups (FGs) with city and town journalists from six states and interviews with local journalists with international exposure. This qualitative information, together with evidence from in-depth reports from local and international organizations and court sentences, offers important clues to who possibly kills local journalists and why.

For the statistical analysis we rely on the Attacks on Journalists in Mexico (AJM) dataset, which we constructed. A master dataset of 166 journalists killed between 1994 and 2019, AJM compiles information from detailed reports developed by three international NGOs (the Committee to Protect Journalists; Article-19; and the International Press Institute) and a local network of female Mexican journalists (Reporteras en Guardia) (refer to online appendix I). We also draw on detailed data from various official and media sources about the presence and intensity of military deployments as well as the localized conflicts that ensued.

To causally identify the effects of the military intervention on attacks, we exploit the staggered deployment of federal troops throughout the Mexican territory. Evidence from a wide variety of statistical models confirms that dynamics related to Mexico’s War on Drugs were major drivers of attacks on journalists. Results from difference-in-differences models show that, while levels of violence against journalists were similar before the War on Drugs in militarized and non-militarized states, the probability of a journalist being murdered in a militarized Mexican state between 1994 and 2015 increased by 24% after the federal government ordered a military campaign to fight the cartels in 2006. Our findings underscore that violence against the press was particularly pronounced in states experiencing more intense military campaigns, where more military personnel were deployed. We then assess the likely impact of the localized armed conflicts and power struggles triggered by the intervention, showing that the odds of assassinations increased in municipalities experiencing 1) the use of the cartel decapitation strategy by which the military arrested or killed “kingpins”; 2) the onset of new inter-cartel conflicts; 3) the development of subnational criminal governance regimes; and 4) the highest counts of forced disappearances—a primary governance tool in Mexico’s criminal wars and the operation of illicit economies.

To explain the mechanics of the assassinations, we primarily draw on three FGs that we conducted in partnership with the Mexico Office of Article-19 – an international organization that promotes press freedom worldwide (refer to online appendix II). FG participants identified criminal lords and subnational government officials as the likely perpetrators of attacks and risk mitigation of unwanted information as their main motivation. Although sometimes they described material perpetrators as independent actors, they consistently remarked that perpetrators were embedded in state-criminal networks. Participants identified four logics. First, drug lords and their private militias kill journalists to prevent or punish the publication of unwanted information on battlefield dynamics that may jeopardize their self-preservation in war. Second, criminal lords and subnational police and judicial officials murder journalists to prevent or punish publications that may endanger their political-business survival by exposing the complicit relations that enable the operation of multiple illicit economies, the development of criminal governance regimes, and their access to extraordinary illicit rents. Third, subnational police and judicial officials kill journalists to prevent or punish the publication of information about widespread disappearances and clandestine mass graves, the public exposure of which would put politicians at grave political and judicial risk. Finally, FG participants also suggested that criminal lords and their subnational government associates murder journalists to reassert themselves as de facto local rulers and to show that anyone who questions or fails to comply with criminal governance will be eliminated.

Prevalent Explanations of Lethal Attacks against Journalists

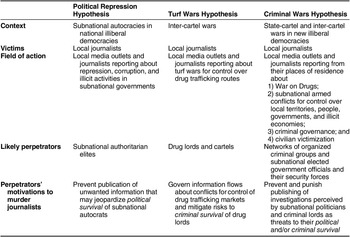

A longstanding tradition in media studies holds that non-democracies and countries experiencing interstate or civil wars are the most lethal places for journalists (Simon Reference Simon2015). New cross-national and subnational research suggests, however, that attacks against the press are more common against local journalists than against national or international journalists (CPJ 2020); in democracies than in non-democracies (Asal et al. Reference Asal, Krain, Murdie and Kennedy2018; Carey and Gohdes Reference Carey and Gohdes2021); and in drug wars than in interstate and civil wars, as “covering politics, crime, and corruption can be equally or more deadly than covering a full-scale war” (CPJ 2023). Scholars have offered two influential explanations: the political repression hypothesis and the turf wars hypothesis. Table 1 summarizes both explanations alongside an alternative path we propose: the criminal wars hypothesis.

Table 1 Prevalent and new explanations of lethal attacks against the press

The Political Repression Hypothesis

Cross-national studies of press freedom have shown that the greatest proportion of journalist killings in the world in the past two decades have taken place in democracies (Carey and Gohdes Reference Carey and Gohdes2021; Hughes and Vorobyeva Reference Hughes and Vorobyeva2021). However, as summarized in table 1, these are not liberal but illiberal democracies, characterized by free and fair elections but ineffective or corrupt security and judicial systems and a weak rule of law. In these national democracies where multiple subnational regions tend to be under the control of strong authoritarian elites, locally elected subnational officials order the assassination of local journalists to prevent the publication of information that reveals their involvement in repression, corruption, or illicit activities (Bartman Reference Bartman2018; Carey and Gohdes Reference Carey and Gohdes2021), and they often get away with murder because impunity prevails (Hughes and Vorobyeva Reference Hughes and Vorobyeva2021). This is an argument about the political survival of subnational authoritarian elites in democracies.

While we acknowledge the importance of recognizing the incentives of subnational authoritarian elites to silence the press in Mexico, an exclusive focus on state actors can overestimate the role public officials play in the assassination of journalists and underestimate the role OCGs play—in collusion with state actors—in violently silencing the press. An exclusive focus on political structures, omitting the impact of the War on Drugs and the multiple armed conflicts it unleashed, would overlook the most severe risks that local journalists face in Mexico.

The Turf Wars Hypothesis

Subnational studies of press freedom in Mexico suggest that the assassination of journalists is intimately related to the country’s inter-cartel wars (Holland and Ríos Reference Holland and Ríos2017). Battling over the control of drug trafficking routes, drug lords order the assassination of journalists to gain control of information flows pertaining to these armed conflicts. They use exemplary lethal violence against journalists to de facto control what gets published, what gets censored, and the framing of the news (Dorff, Henry, and Ley Reference Dorff, Henry and Ley2023). They want journalists to become their mouthpieces or at the very least to practice self-censorship, and they kill those who do not follow their orders or who follow their rivals’ commands (Holland and Ríos Reference Holland and Ríos2017). Although the Mexican government launched a War on Drugs, in this interpretation public authorities have no role in attacking the press; it is all about inter-cartel wars. This is an argument about the criminal survival of drug lords.

While the turf wars hypothesis correctly identifies incentives for drug lords to violently silence the press, an account solely based on cartels’ interests and inter-cartel conflicts underestimates the potential role of government officials and security forces in brutally suppressing information. It overlooks the potential impact of the deployment of the army in the War on Drugs and the likely involvement of subnational government officials in silencing the press. And it underestimates the extraordinary risks associated with reporting about the reconfiguration of local social and political orders associated with criminal wars.

The Criminal Wars Hypothesis: A New Explanation

In developing our own propositions, we follow the literature’s shift from national to subnational political and conflict dynamics and the focus on local journalism. We depart, however, in three important respects. First, we bring the state back in and explore the likely impact that the federal government’s War on Drugs and the resulting multiple turf wars had on assassinations. Second, we go beyond an exclusive focus on turf wars and assess the impact of the multiple armed struggles for criminal and political power. Third, rather than explain attacks against journalists either as a government- or a narco-driven phenomenon, we look at the likely joint production of violence against the press by networks of subnational government officials and criminal lords.

As table 1 summarizes, our central proposition is that local journalists face major risks to their personal safety when they report on criminal wars. As seen in a wide variety of conflicts, from Brazil and Mexico to El Salvador and Guatemala, state-cartel and inter-cartel wars often result in protracted armed conflicts and unusually high levels of civilian deaths and mass atrocities (Flores-Macías and Zarkin Reference Flores-Macías and Zarkin2023). The Mexican government’s decision to declare a War on Drugs against the country’s leading drug cartels, deploy the military to arrest the cartel leaders, and recover subnational territories under the cartels’ control triggered multiple localized turf wars (Calderón et al. Reference Calderón, Robles, Díaz-Cayeros and Magaloni2015), widespread violence (Flores-Macías Reference Flores-Macías2018), gross human rights violations (Magaloni and Rodríguez Reference Magaloni and Rodríguez2020; Flores-Macías and Zarkin Reference Flores-Macías and Zarkin2023), and the reconfiguration of local orders (Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2020). The kingpin strategy triggered major intra-cartel succession disputes and the fragmentation of cartels and their private militias into hundreds of breakaway and new groups that fought for control over drug trafficking routes and new illicit economies that would enable them to remain competitive in the struggle over drug trafficking routes (Calderón et al. Reference Calderón, Robles, Díaz-Cayeros and Magaloni2015; Phillips Reference Phillips2015; Atuesta and Ponce Reference Atuesta and Ponce2017). Executions, torture, and disappearances in these conflicts became widespread. And when cartels engaged in struggles to control new illicit economies centered on the illegal extraction of human or natural resource wealth, they sought to become local de facto rulers and develop subnational criminal governance regimes (Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2020; Lessing Reference Lessing2021).

Our explanation posits that local journalists are the main victims and local journalism is the main field of action for three reasons. First, because most transnational organized criminal industries are global chains of local operations, control over subnational territories, local governments and societies, and security forces is crucial for anyone who aspires to dominate any illicit economy (Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2020). Successful drug trafficking operations invariably involve collusion between drug lords and governors, mayors, and their security officials. Not all subnational officials collude, but illicit economies cannot prosper without state complicity. Second, criminal wars often entail the outbreak of localized armed disputes over the control of illicit economies and the reconfiguration of local social orders. Third, to remain in business and fulfill their professional duty to inform local societies, local media outlets continue to report the local operations taking place in criminal wars. Crucially, local journalists report on the multiple political and criminal actors involved in drug trafficking operations and armed conflicts occurring in their place of residence, where their proximity to the events combined with their professional investigations gives them access to fine-grained information. This quotidian proximity to the main protagonists and events in criminal wars turns local journalism into a deadly profession. To protect themselves, editors learn how to disclose sensitive information and sometimes even practice self-censorship (Dorff, Henry, and Ley Reference Dorff, Henry and Ley2023), while journalists develop networks of support that enable their reporting (Salazar Reference Salazar2023).

Local reporting about criminal wars entails major risks for journalists because disclosing fine-grained information about these disputes can upset the balance of power in the criminal underworld, jeopardizing some political-criminal actors at the cost of others. Affected drug lords and subnational government officials have independent or joint incentives to mitigate these risks through bribes, threats, and lethal violence. When bribes become too expensive and threats prove inefficient in deterring local journalism from publishing unwanted information (Lawson Reference Lawson2002), they become motivated to use lethal violence as exemplary punishment for past news stories (Carey and Godhes Reference Carey and Gohdes2021) or to prevent future ones (Dorff, Henry, and Ley Reference Dorff, Henry and Ley2023).

Figure 1 identifies the multiple conflicts and power struggles unleashed by the War on Drugs in Mexico and outlines the causal process that explains why investigating specific aspects of these conflicts rendered local journalists vulnerable to lethal attacks. Rather than focus on the impact of a single dimension of Mexico’s criminal wars (e.g., the state’s War on Drugs or inter-cartel wars), we look holistically at multiple dimensions of these wars, from battlefield dynamics in state-cartel conflicts (H1), the state’s use of the “kingpin” strategy (H2) and the intensification of inter-cartel wars (H3), to the reconfiguration of de facto local orders (H4) and civilian victimization (H5). Figure 1 also identifies the causal process that explains why perpetrators were motivated to victimize the local press.

Figure 1 The theoretical path from the war on drugs and the multiple conflicts it unleashed to the assassination of local journalists

Reporting on State-Cartel Wars

For local journalists, the risk of attacks during military interventions stems from two sources. First, federal authorities, military campaign leaders, and members of the military fighting the cartels have powerful incentives to suppress investigations about atrocities committed in the War on Drugs. Under close national and international scrutiny, however, they may be unable to use lethal violence and instead be inclined to prevent publication of revealing local information using bribes or covert repression (Lawson Reference Lawson2002) or even outsourcing lethal attacks to subnational authorities—and then provide them with impunity in federal judicial institutions. Second, in confronting military interventions, drug lords and their lieutenants have strong incentives to conceal information about the logistical operations of war (Durán-Martínez Reference Durán-Martínez2018)—including their places of residence, the acquisition of weapons, and the recruitment of foot soldiers and their military capacity to repel a military crackdown. They may also want to conceal information about their informal partnerships with subnational government authorities who inform them about the details of military campaigns. Because subnational government authorities and drug lords face few constraints on the use of lethal violence, they may be inclined to murder journalists to mitigate risks associated with the publication of compromising information about state-cartel wars. We expect that

H1. Journalists are more likely to be killed after national governments launch military wars against drug cartels, particularly in subnational regions where the armed forces are deployed.

Reporting on the Decapitation Strategy

In the federal government’s War on Drugs, the assassination or arrest of a drug lord, the leader of a private militia, or the plaza chief of a geo-strategic drug-trafficking corridor often leads to major internal succession struggles marked by betrayal, fragmentation, and the violent reconfiguration of alliances within and between cartels and private militias (Calderón et al. Reference Calderón, Robles, Díaz-Cayeros and Magaloni2015; Phillips Reference Phillips2015; Atuesta and Ponce Reference Atuesta and Ponce2017). Because these struggles determine who survives and who rules the criminal underworld, reporting on these conflicts can be highly sensitive. By publishing fine-grained and sensitive information about the parties in conflict, local journalists can influence the balance of power within and between criminal organizations. Cartel leaders, army lieutenants, or plaza chiefs involved in succession struggles are likely to use lethal violence to punish local journalists for publishing or to prevent the publication of information that reveals weaknesses that may render them vulnerable to intra-group factional struggles or to rival OCGs. We expect that

H2. Journalists are more likely to face lethal attacks after the army adopts the kingpin strategy, decapitating cartels by arresting or killing drug lords and leaders of private militias.

Reporting on Inter-cartel Wars

Cartels have strong incentives to control information flows in turf wars and to mitigate risks to their self-preservation. They are particularly concerned about how the press reports on and frames these wars. Information about the outcome of military campaigns, including battle deaths, and territorial control can reveal the relative weakness of a cartel or a militia, rendering them vulnerable to rival attacks. Drug lords will want to control the flow of information about their military power and strategies and their networks of informal subnational government and civilian support. But they may also want to use news outlets as mouthpieces, overstating conflicts in enemy territory to attract national crackdowns and downplaying conflict in their own territories to dissuade interventions (Holland and Ríos Reference Holland and Ríos2017). Reporters, editors, and news outlet owners who resist publishing or manipulating news to serve cartel interests may become the target of lethal attacks (Dorff, Henry, and Ley Reference Dorff, Henry and Ley2023). We expect that

H3. The intensification of inter-cartel wars is associated with increases in the number of journalists assassinated.

Reporting on Criminal Governance

When drug lords and their political allies seek to develop subnational criminal governance regimes, by which they become de facto rulers of local territories, municipal governments, and local societies and economies (Lessing Reference Lessing2021; Feldmann and Luna Reference Feldmann and Luna2022), they have incentives to strictly control information flows in towns, villages, and cities. As Trejo and Ley (Reference Trejo and Ley2020) suggest, in Mexico criminal lords and their state allies use lethal violence against party candidates in subnational election cycles to remove and impose candidates of their own, penetrate municipal governments, and influence the appointment of key personnel in the municipal police, the public registry, and the directorates regulating local economic activities. From these positions of power, they seize control over a wide variety of illicit economies involving the illegal exploitation of human wealth—including criminal taxation, property grabs, and the forced recruitment of young people for labor and sexual exploitation—and of natural wealth—including the looting of forests, mining, water, and agricultural production. To maintain social order, they use selective violence against local leaders and elites, selectively distribute private goods, and sometimes engage in public goods provision (Arias Reference Arias2017).

Criminal lords and their allies may be inclined to murder local journalists to prevent the publication of information that shows their de facto control of municipal governments. Shedding light on criminal governance may attract federal intervention and jeopardize the narco-political networks’ hold on de facto local power. Drug lords and their political associates may also use lethal violence to force the press to report news in ways that facilitate de facto criminal rule. They may want local newspapers to report acts of targeted violence—like the assassination of local business owners who dare to refuse to pay criminal taxes—in such a way that the consequences of defiance become common knowledge without necessarily attracting unwanted national attention (e.g., publishing in the back of the paper). We expect that

H4. Journalists are more likely to be killed in municipalities where drug cartels and OCGs, in collaboration with their political associates, have created subnational criminal governance regimes.

Reporting on Disappearances

Disappearances represent the leading human rights violation associated with criminal wars and the operation of illicit economies in Mexico (OSJI 2016). Reporting on disappearances entails heightened risks for two reasons. First, in state-cartel and inter-cartel wars, security forces and drug cartels kill and often hide their rivals (Durán-Martínez Reference Durán-Martínez2018) and civilians in clandestine mass graves (Guillén, Torres, and Turati Reference Guillén, Torres and Turati2018). Because perpetrators seek to conceal victims, journalists challenge de facto rulers and endanger their political or criminal survival when they identify patterns of disappearances or report on clandestine mass graves. Second, because state-criminal networks use disappearances as a tool of criminal governance (e.g., to punish those who fail to pay criminal taxes or to recruit foot soldiers for war), any report on disappearances or clandestine mass graves may jeopardize their ability to rule. We expect that

H5. Journalists face greater risks of assassinations in municipalities with higher counts of disappearances.

The Assassination of Journalists in Mexico: Patterns and Targets of Victimization

Drawing on AJM, an original dataset compiling information from four different national and international sources, we use descriptive data about the main features of the wave of attacks on journalists in Mexico to assess the plausibility of alternative explanations and to visualize the potential of our own argument.Footnote 1

The War on Drugs and the Outbreak of Attacks

Figure 2 plots 166 murders of journalists in Mexico, from 1994 to 2019. The figure unambiguously shows the outbreak of multiple waves of assassinations after the Mexican federal government launched a major war against the cartels in 2005–2007. President Vicente Fox’s “México Seguro” campaign, in which the federal government deployed the military in 2005 to contain a major outbreak of inter-cartel conflict in Tamaulipas (Lessing Reference Lessing2017), served as the war’s prelude. Escalating his predecessor’s strategy, in 2006 President Calderón declared war on the cartels, deployed the military and the federal police to the country’s most conflictive regions, and adopted a “kingpin” strategy to decapitate the cartels. The arrest of multiple cartel leaders and chiefs of their private militias led to the rapid fragmentation of the criminal underworld and the proliferation of turf wars. The renewed deployment of the military to fight these breakaway groups during the later years of Calderón’s presidency and throughout the administration of Enrique Peña Nieto (2012–2018) led to an eightfold increase in violence (Flores-Macías Reference Flores-Macías2018), including multiple waves of journalists’ assassinations.

Figure 2 Assassination of journalists in Mexico, 1994–2019

The time series of attacks suggests four conclusions. First, 2006 was an inflection point in the history of the Mexican press: the beginning of major waves of lethal attacks that turned Mexico into the world’s deadliest country for journalists. Second, the military interventions seem to be the most proximate antecedents of the multiple waves of attacks. This strongly suggests that while the state intervention did trigger multiple inter-cartel wars (Calderón et al. Reference Calderón, Robles, Díaz-Cayeros and Magaloni2015), a narrow focus on turf wars would underestimate the impact of the federal intervention. Third, although inter-cartel wars first broke out in the 1990s (Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2020), in the absence of state-cartel wars there was no corresponding wave of attacks on journalists. Finally, while attacks have taken place in democracy (Salazar Reference Salazar2023), figure 1 shows no evident democratization effect. Mexico transitioned to democracy in 2000 but the wave of assassinations broke out six years into democracy.

Geography of Attacks

Figure 3 displays the geographic distribution of the assassination of journalists across states and municipalities. It reveals that most attacks took place in subnational regions with intense histories of state-cartel and inter-cartel wars, including: 1) the Gulf of Mexico (Tamaulipas, Veracruz, Tabasco) and the Caribbean (Quintana Roo); 2) the Pacific coast (Sinaloa, Michoacán, and Guerrero); 3) the U.S.–Mexico border (Chihuahua); 4) the Central Valleys (Mexico City, State of Mexico, and Morelos); and 5) the South (Oaxaca). In all these regions (except for the South), the military was deployed in at least one state to fight the cartels.

Figure 3 The geography of journalist attacks in Mexico, 1994–2019

A key feature about the geography of attacks is that the majority of assassinations took place in medium and small cities. As figure 4 shows, while 40.59% of the murders did happen in the states’ three most populated and predominantly urban municipalities, including the capital (refer to municipalities ranked first, second, and third), nearly 60% of attacks took place in a wide variety of medium and small cities and towns (refer to municipalities ranked fourth and above). These are municipalities with predominantly urban or semiurban seats but large rural peripheries. Because the headquarters of local media outlets are located in the larger municipalities or the municipal seats of medium or small municipalities, it is safe to conclude that the majority of murdered journalists lived in urban centers. Note, however, that a significant number of them covered events in rural areas outside their municipal seats, where armed groups typically have their security houses, land and natural resources are under fierce dispute, and thousands of bodies are buried in clandestine mass graves.

Figure 4 Journalist attacks by within-state municipal population size (%)

Note: The figure shows the percentage of all journalists killed in Mexico by municipalities ranked by population size within each state.

Targets of Attacks

Consistent with the literature’s new focus on local journalism, 90% of victims in Mexico worked for subnational news outlets, as shown in figure 5. Within subnational regions, 57% worked for city- or town-level outlets and 34% for statewide outlets in the capital cities. Taken together, information from figures 4 and 5 strongly suggests that most lethal attacks are directed at local journalists who cover events in medium and small cities and towns. While most victims worked for daily newspapers, a significant number were also active in local radio programs and had their own digital news platforms. On average, journalists killed worked for 1.47 outlets.

Figure 5 Assassinated journalists by news outlet geographic coverage in Mexico, 1994–2019

Note: Local outlets have their headquarters in medium and small municipalities; regional outlets in state capitals; national media outlets in Mexico City; and international outlets outside Mexico.

As shown in figure 6, the majority (53%) of local journalists killed were reporters, investigative journalists, and photojournalists—who often jointly conduct investigations (Article-19 2024). They are the on-the-ground media personnel who rush to the crime scene after an assassination or a massacre or when a clandestine mass grave is discovered; the ones who chase down the facts from military facilities, public prosecutors’ offices, the police, professional witnesses, and prison guards. But editors and local media owners, who decide what gets reported and published and the framing and prominence of the news (Hughes and Márquez Ramírez Reference Hughes and Ramírez2017; Dorff, Henry, and Ley Reference Dorff, Henry and Ley2023), were also targets of attacks (27%).

Figure 6 Assassinated journalists by occupational rank in news outlet in Mexico, 1994–2019

Murdered journalists worked on substantive areas related to crime, security, and political corruption (Bartman Reference Bartman2018; Hughes and Márquez Ramírez Reference Hughes and Ramírez2018). As shown in figure 7, journalists covering crime and security (31%), politics (25%), corruption (17%), and social movements and human rights violations (10%) comprise over 80% of lethal victims. But their beats were not monothematic; on average, journalists murdered during this period covered 1.83 topics. The Venn diagram in figure 8 plots the different combinations for journalists working on crime and security, politics, and corruption, showing that more journalists were killed working at the intersections of these topics than those covering these topics in isolation.

Figure 7 Assassinated journalists by topic of reporting in Mexico, 1994–2019

Figure 8 Thematic intersections in reporting by journalists assassinated in Mexico, 1994–2019

Note: Numbers are journalists assassinated.

Criminal Wars and Violence against the Press: Quantitative Tests

To quantitatively assess the impact of the War on Drugs and the conflicts it unleashed, we use information from the AJM dataset. Our dependent variable is a count of journalists killed in each state- or municipality-year. Because the federal government launched military campaigns using states as the relevant jurisdiction for interventions (Flores-Macías Reference Flores-Macías2018), we use states as units of analysis to evaluate the impact of the military intervention on attacks. However, because this meso-level intervention triggered multiple local-level conflicts, we also use municipalities as units of analysis.Footnote 2

State-Level Data

Our theoretical story begins with the War on Drugs and the government deployment of the armed forces and the federal police in joint operations to fight drug cartels. The federal intervention took place in staggered military campaigns, beginning in 2006 in Michoacán, President Calderón’s home state. This staggered deployment of the military across states continued for the remainder of the Calderón administration (2006–2012) and throughout Peña Nieto’s (2012–2018), covering large swaths of the country’s territory. Following Flores-Macías (Reference Flores-Macías2018) and Atuesta (Reference Atuesta, Atuesta and Madrazo2018), we test for the impact of military presence (the launching of a military campaign) and military intensity (boots on the ground). We test for different sources because there is disagreement about the exact timing and extent of the military interventions.

Military presence. The deployment of federal troops as part of the Military intervention in the War on Drugs is our primary treatment (H1). We use three different versions of this variable to assess the robustness of our results to alternative measures. In our main operationalization, a state-year takes on a value of one if a military campaign took place in any month of that year, as reported by the Office of the Mexican President and recorded by Flores-Macías (Reference Flores-Macías2018). These massive operations, in which the military played a leading role, involved the deployment of around 45,000 troops across multiple states, as well as dozens of aircraft and hundreds of vehicles for aerial and ground patrols. In these campaigns officials established checkpoints on federal and state highways to control drug trafficking operations and built new military garrisons in multiple regions of each state. We use two alternative measures drawing on the Ministry of Defense (SEDENA) reports on military operations and on confrontations between state security forces and criminal groups, including the number, date, and place of casualties and arrests, as reported by CIDE’s Drug Policy Program (Atuesta Reference Atuesta, Atuesta and Madrazo2018). We use the date when clashes between state security forces and armed criminal groups were first reported as a proxy for the start date of the federal intervention in each militarized state.

Military intensity. We use SEDENA information on the number of troops involved in each military operation, as reported by Atuesta (Reference Atuesta, Atuesta and Madrazo2018). Reports suggest wide variation in the number of military personnel deployed across states: whereas the “Operativo Conjunto Tamaulipas-Nuevo León” deployed 10,562 agents, the “Operativo Conjunto Chihuahua” only deployed 227 officers. Because this information is uneven, we also test for Atuesta’s (Reference Atuesta, Atuesta and Madrazo2018) own alternative measure of intensity, which supplements SEDENA data with open press sources.

Confounders. Although our statistical models control for all time-invariant characteristics, we employ time-varying covariates used in other studies to explain criminal violence (Calderón et al. Reference Calderón, Robles, Díaz-Cayeros and Magaloni2015; Flores-Macías Reference Flores-Macías2018; Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2020). Our state level models include the subnational level of criminal violence, measured as the Homicide rate (in the previous year); state capacity, measured in terms of Debt- and Tax-to-GDP ratios; economic development, as captured by GDP per capita; government coordination, operationalized as Vertical political fragmentation (a dummy variable that indicates whether the governor and the president belong to different parties); and levels of social development, measured in terms of Educational attainment (in years).

Municipal-Level Data

To assess the impact of the multiple localized armed conflicts (H2 and H3), local power struggles (H4), and disappearances (H5) we use municipal-level data.

To measure the Decapitation of a criminal organization by federal forces, we code a municipality-year as one if a drug leader or a private army lieutenant is killed or arrested in that municipality or in a neighboring municipality, as reported by Calderón et al. (Reference Calderón, Robles, Díaz-Cayeros and Magaloni2015). We use this operationalization because drug cartels and other OCGs tend to operate in clusters of adjacent municipalities—what happens in one municipality affects their neighbors too.

To measure Inter-cartel wars, we use battle deaths per 1,000 population in inter-cartel conflicts. Based on a systematic review of three Mexican newspapers, this variable measures conflict-related murders in wars between rival criminal organizations, which we retrieved from the Criminal Violence in Mexico (CVM) dataset (Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2020), covering the 1995–2012 period.

Because criminal governance in Mexico’s 2,447 municipalities is hard to measure, we follow Trejo and Ley (Reference Trejo and Ley2020), who suggest that cartels often develop subnational criminal governance regimes in municipalities where drug lords have previously murdered party candidates and local government officials. We use the total number of attacks on party candidates and local government officials in the previous three years as a proxy for Criminal governance because these attacks increase during municipal election cycles (which occur every three years) as power rotation opens up the door for the development of subnational criminal regimes (Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2020) and because the criminal colonization of municipalities is a multi-stage phenomenon that takes several years to materialize. We show that our results are robust to attacks in the past two-, three-, four-, and five-year periods. Our indicator measures a common path by which OCGs and their political allies establish de facto criminal governance, but it does not tell us much about how they regulate social life.

To measure Disappearances, we use an official count of people reported as disappeared by municipality.Footnote 3

Our municipal-level analyses control for two plausible alternative explanations: indiscriminate criminal violence and state capacity. First, we include the Homicide rate (in the previous year) to test the alternative hypothesis that journalists are killed for reasons unrelated to their professional activity (Bartman Reference Bartman2018). Second, because it is possible that subnational regions with a more robust rule of law are better able to deter violence against journalists (Carey and Gohdes Reference Carey and Gohdes2021), we control for the number of Public prosecutors per 10,000 population.

Empirical Strategy

Isolating the causal effect of warfare dynamics on the assassination of journalists is difficult because other factors may simultaneously affect both the multiple localized military conflicts triggered by the federal military intervention and the likelihood of attacks on the press. Similarly, the militarization of public security may occur where journalists are at higher risk in the first place. To overcome these methodological challenges, we first run a series of generalized difference-in-differences (DID) models, exploiting the staggered deployment of federal forces into some (but not all) Mexican states. Instead of simply relying on cross-sectional comparisons, in our empirical strategy the difference in average pre-treatment murders between militarized and non-militarized units is subtracted from the difference in average post-treatment outcomes between treated and control units. Such a design allows us to control for all time-invariant state characteristics that may be correlated with lethal attacks on journalists and for conflict levels common to all Mexican states in a given year. DID models do not require that the number of journalists killed is the same in militarized and non-militarized regions, but their plausibility rests on the parallel trends assumption, which we address in the next section and in online appendix VI. Our primary strategy for modeling the assassination of journalists leverages the timing of the deployment of the army across Mexican states and the intensification of criminal wars across municipalities.

Unless otherwise noted, we test our hypotheses by estimating the following Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) equation:

where

![]() $ {y}_{st} $

is the count of journalists assassinated in any given state (or municipality) and year or a dummy variable indicating whether a journalist was assassinated in each unit-year;

$ {y}_{st} $

is the count of journalists assassinated in any given state (or municipality) and year or a dummy variable indicating whether a journalist was assassinated in each unit-year;

![]() $ {T}_{st} $

is a variable that indicates our treatments (e.g., militarization at the state level and decapitation or inter-cartel wars at the municipal level);

$ {T}_{st} $

is a variable that indicates our treatments (e.g., militarization at the state level and decapitation or inter-cartel wars at the municipal level);

![]() $ {\mathbf{X}}_{\mathbf{st}} $

is a vector of time-varying covariates; and

$ {\mathbf{X}}_{\mathbf{st}} $

is a vector of time-varying covariates; and

![]() $ {\unicode{x03B4}}_s $

and

$ {\unicode{x03B4}}_s $

and

![]() $ {\unicode{x03B3}}_t $

correspond to geographic and year fixed effects, respectively. We use this specification to test for H1–H5 and document the robustness of our findings to alternative model specifications in online appendix IV. We leverage recent advances in the methodological literature to estimate a dynamic DID model exploiting the staggered timing of the militarization across states.

$ {\unicode{x03B3}}_t $

correspond to geographic and year fixed effects, respectively. We use this specification to test for H1–H5 and document the robustness of our findings to alternative model specifications in online appendix IV. We leverage recent advances in the methodological literature to estimate a dynamic DID model exploiting the staggered timing of the militarization across states.

Results

Military Intervention

Primary measure of military presence. We begin by testing the impact of the War on Drugs using our primary measure of military presence retrieved from Flores-Macías (Reference Flores-Macías2018). Consistent with H1, the results in table 2 suggest that joint military operations in the War on Drugs dramatically increased journalists’ vulnerability to lethal attacks. Models 1–3 employ the state-year count of journalists assassinated as the outcome, whereas models 4–6 use a dummy indicating whether one or more journalists were killed in a specific state during a given year. Models 1 and 4 include no covariates, while Models 2 and 5 incorporate time-varying controls to further mitigate confounding the treatment. Finally, Models 3 and 6 replace the dummy variables for each year with a linear time trend. While all these approaches wash out time trends, our preferred specifications include time fixed effects (Models 2 and 5), which allow nonlinear yearly shocks.

Table 2 The impact of militarization on attacks on journalists by Mexican State, 1994–2015

Note: Entries are coefficients from OLS regressions. Standard errors clustered at the state level in parentheses.

+ p<0.1

* p<0.05

** p<0.01

*** p<0.001.

Regardless of the specification, we find that journalists were disproportionately targeted in militarized states relative to non-militarized ones. Our results are statistically significant and substantively strong. Models 1–3 indicate that joint operations in militarized states increased the count of journalists assassinated by between 0.55 and 0.70. This represents a differential increase of around four times the sample mean, and over one standard deviation. Models 4–6 show similar information, but the transformation of the outcome into a binary variable permits a more direct interpretation. Coefficients in columns (4) through (6) show that militarized operations substantially boosted the murder of journalists by between 21 and 27 percentage points.

Our identification strategy relies on the parallel trends assumption that changes over time in control units offer a good counterfactual for changes that would have occurred had states not been militarized. We examine the plausibility of this assumption through placebo tests to check that the effect of the joint operations on the assassination of journalists is statistically insignificant before the deployment of federal troops. If our argument is correct and joint operations disproportionally affected militarized states, our treatment should only have an effect after the deployment.

Following Sun and Abraham’s (Reference Sun and Abraham2021) procedure for estimating dynamic treatment effects, figure 9 plots the placebo tests by year before and after the militarization strategy to show the size of its impact in the context of parallel trends. The graph indicates that the effect was indistinguishable from zero and without any detectable pattern before the War on Drugs, implying that prior to the deployment of federal troops the assassination of journalists in militarized and non-militarized states followed the same trend. Yet we find that right after the treatment comes into effect—when the military campaigns are launched—the impact of militarization on attacks on journalists becomes positive and significant, lending confidence to the assumption that without militarization the trends in the outcome would have likely remained the same in both groups.Footnote 4 The magnitude of the average treatment effect is substantial: once the treatment kicks in, it increases from -0.04 to 1.02.

Figure 9 Effect of militarization on the murder of journalists over time

Alternative measures of military presence. We employ two alternative measures of military presence reported by SEDENA and CIDE. One important difference between these two sources is that whereas for CIDE 25 out of 31 states had been militarized by 2012, for SEDENA only 11 out of 31 states were. Despite these important differences, statistical models show that the deployment of the army increased the number of journalists assassinated by 0.41–0.44 when using official SEDENA data and by 0.18–0.20 when employing CIDE information (refer to online appendix IV, table A.IV.b). Both sets of results are statistically significant, constituting a 12.5%–175% increase of the sample mean and 34%–83% of the standard deviation.

Military intensity. Using information about military intensity (boots on the ground) adds more nuance. The results suggest that lethal attacks against journalists rise as the number of state security forces deployed in military operations increases (refer to online appendix IV, figure A.IV.a). Specifically, official SEDENA data indicate that, compared to contexts without operations, states with the largest number of recorded military troops show an additional 0.32 journalists killed (p < 0.05). The magnitude of the effect is even stronger when we complement official data with press information. Moving from the minimum number of troops to the maximum is equivalent to an extra 0.43 journalists killed (p < 0.001). Military campaigns do increase risks of attacks but risks for journalists are even greater in states with more boots on the ground.

Cartel Decapitation

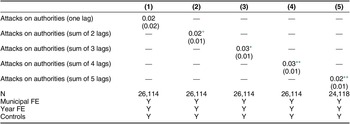

Using municipalities as units of analysis, we next investigate whether the decapitation of drug cartels and their private militias increased the odds of attacks against journalists (H2).

Our findings, summarized in table 3, show that the use of the kingpin strategy contributed to creating the context in which journalists were assassinated. Model 1 indicates that in municipalities affected by the killing or arrest of drug lords or their lieutenants, the average number of journalists murdered disproportionately increased by 0.029, which represents over 15 times the dependent variable sample mean and more than half of its standard deviation—a statistically significant and substantially large shift. Model 2 reports that the removal of at least one cartel leader is associated with a two-percentage-point increase in journalist assassinations.

Table 3 Cartel decapitation and inter-cartel wars predict attacks on journalists by Mexican municipality

Note: Entries are coefficients from OLS regressions with standard errors in parentheses. All models control for the number of Public Prosecutors per 10,000 population. Models 1 and 2 also control for the municipal Homicide rate in t-1.

+ p < 0.1

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01

*** p < 0.001.

Inter-cartel Wars

We now use municipalities as units of analysis to test for the impact that the intensification of inter-cartel wars (H3) had on attacks against the press.

As reported in table 3, our results also show that inter-cartel wars heightened the risk of attacks. Model 3 suggests that moving from a municipality without inter-cartel wars to one with the maximum violence is associated with an increase in the number of journalists assassinated of 0.05, a value 25 times greater than the sample mean or one standard deviation. Model 5, in turn, suggests that moving from the minimum level of drug-related violence to the maximum increases the risks of assassination for journalists by five percentage points.Footnote 5 Models 4 and 6 alternatively replace the continuous treatment for a binary indicator of inter-cartel violence, which can be interpreted as switching the treatment on and off. The result is substantively and statistically similar: the odds of attack against the press are greater in municipalities experiencing inter-cartel wars than in those that do not.

Criminal Governance

The War on Drugs stimulated a major reconfiguration of local power. We suggested in H4 that journalists reporting on how cartels developed subnational criminal governance regimes were vulnerable to attacks.

Using lethal attacks on mayors and party candidates as a proxy for criminal governance, table 4 shows that political assassinations in the two, three, four, and five previous years are strong predictors of heightened risks of attacks against the press. Models 2–5 show that criminal governance is a statistically significant and substantively important driver of attacks on journalists. The results indicate that municipalities with histories of assassination of local government officials and party candidates, where drug cartels and other OCGs often developed subnational criminal governance regimes, were more likely to experience lethal attacks on journalists than municipalities where there was no criminal governance. In our preferred model, encompassing the political assassinations in the three previous years, each additional attack on local government officials and party candidates is associated with an increase of 0.03 journalists assassinated. Moving from the minimum to the maximum number of political assassinations entails an additional 0.24 journalists murdered.Footnote 6

Table 4 Criminal governance and the murder of journalists by Mexican municipality, 1995–2012

Note: Entries are coefficients from OLS regressions with standard errors in parentheses.

+ p < 0.1

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01

*** p < 0.001.

Disappearances

The War on Drugs and the multiple struggles it unleashed led to a major wave of forced disappearances and reporting on disappearances, we conjectured, should heighten risks for journalists (H5).

Table 5 confirms that the number of disappearances correlates with greater violence against journalists. Specifically, each additional disappearance is associated with an additional 0.0014372 journalists murdered, which means that moving from the minimum (0) to the maximum (411) number of municipality-year disappearances increases the number of journalists assassinated by 0.59. This is a substantively meaningful association given that the number of journalists assassinated by municipality-year ranges from 0 to 3 with a mean of 0.002 and a standard deviation of 0.049.Footnote 7 , Footnote 8

Table 5 Disappearances and the assassination of journalists by Mexican municipality, 1995–2012

Note: Entries are coefficients from OLS regressions with standard errors in parenthesis.

+ p < 0.1

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01

*** p < 0.001.

The Mechanics of Attacks: Qualitative Evidence

While the quasi-experimental models help us explain when and where journalists are more likely to be attacked, they tell us little about who does it and why. To understand the mechanics of attacks we used FGs for two reasons.Footnote 9 First, FGs are social rather than individualistic sources of information that mirror the inter-subjective processes through which our understanding of phenomena are produced (Cyr Reference Cyr2019). We were particularly interested in group-level dynamics to assess journalists’ collective sense of the nature of criminal wars (e.g., Are these war zones?), the perpetrators’ motivations for the attacks, and how the reporters’ own perspectives are constructed through conversations with their colleagues. We were interested in consensuses and disagreements. Second, FGs provide a safe environment to collect data on sensitive issues, offering a platform for collective support where difficult but common challenges can be discussed openly among individuals facing similar experiences. Respectful and sensitive discussions with at-risk journalists who have lived through the tragic experience of losing a colleague are crucially important.

We held three small FGs with a total of ten local journalists from six different states in June of 2022. Each session included three or four participants because we wanted to provide sufficient time for a meaningful dialogue among professionals who had abundant information and rich journalistic experiences. We leveraged years of collaboration with the Mexico Office of Article-19 and their extensive network of connections with town and city-level journalists in Mexican dangerous zones. FGs were held online to ensure participants’ geographic diversity and safety, as some were living in state-sponsored security houses for journalists facing imminent threats to their lives. Following our theory and statistical findings, we organized the FGs around three topics: risks of reporting on 1) the War on Drugs and the multiple localized conflicts it unleashed; 2) criminal governance; and 3) state-criminal collusion and gross human rights violations. To gain a broader perspective, we complemented our FGs with in-depth interviews with three award-winning local journalists with extensive international exposure and with a U.S. foreign correspondent.

Context: Criminal Wars

All FGs started with a question about the journalists’ identity and the context in which they worked: Do you consider yourselves to be “war journalists”? Most participants rejected this characterization—they reserved that identity for international war correspondents—but they unflinchingly described their fields of action as “war zones” and the conflicts they covered as “uncommon wars” that are “hard to describe.” A participant from the metropolitan area of Guadalajara (Jalisco) claimed that he did not live in and report from a war zone, but he conceded that all other participants did.

Group discussion led to a consensus across groups: war zones are subnational regions where the armed forces and OCGs engage in military combat for “territorial control” and where OCGs and their private armies fight other groups for the control over “criminal taxation,” “illicit economies,” and “political spaces.” Speaking from a state-sponsored security house for journalists at risk, a reporter who has worked in northern Guerrero thus described her local context: “Those of us who report on shootouts and massacres from cities that have been seized by OCGs and where citizens are kept hostage in their own towns and are prevented from free transit; those of us who report on forced disappearances in cities that have become massive cemeteries; those of us who have been held at gunpoint and whose families have been kidnapped; those of us who have lived through these experiences must recognize that we do work in areas that bear no other name than a war zone.”Footnote 10 A senior photographer from Acapulco, Guerrero, who has survived several assassination attempts and who had previously lived in a state-sponsored security house, concurred with this assessment. The description of a single-day journey in which he took photo images of 42 dead bodies in multiple shootouts in Acapulco led him to conclude: “We may not name it as such, but I do work in a war zone.” In an in-depth interview Patricia Mayorga, a Chihuahua-based award-winning journalist, thus put it: “This is not a conventional war, but armed groups in the Sierra Tarahumara are fighting for territorial control and for control over natural resources. There is no ceasefire.”

Participants across FGs noted the high-caliber weaponry used in criminal wars and the military training that criminal foot soldiers receive. An experienced reporter from Zitácuaro, Michoacán, explained that “OCGs and their militias use the same military weapons as the Mexican armed forces.” A photojournalist concurred: “OCGs use armored fighting vehicles, drones, and high caliber machine guns in Michoacán.” A reporter from Jalisco explained that there “cartels use clandestine security houses to train young sicarios (hitmen) into foot soldiers for war.”

FG participants were unanimous about one specific feature of these “uncommon wars”: unlike interstate wars and internal armed conflicts, in which parties to the conflict can be identified, in criminal wars lines of demarcation are blurry. An investigative journalist from Veracruz shared that in her town “it is hard to tell who is shooting the bullets; state-criminal collusion makes it simply impossible to know who pulls the trigger.” Another journalist from Veracruz noted that in these conflicts “it is hard to tell whether the police are the good or bad guys because some of them work for criminals levying criminal taxes.”

Micromotives: Why Are Journalists Killed?

Self-preservation in war. We asked participants in FGs whether and why the War on Drugs and the multiple turf wars it unleashed had heightened risks of assassination for journalists. They identified three motivations that drove criminal lords and their lieutenants to use lethal violence against the press.

First, cartels use selective violence against the press to increase the social and political costs of the federal military intervention and provoke a public backlash. A senior journalist from Sinaloa reminisced that the military intervention in 2008 by which the military arrested Alfredo Beltrán Leyva, the leader of the most powerful private militia of the Sinaloa Cartel, led to a major spiral of violence. After the detention “the Sinaloa Cartel issued an order to their members and to their private militias to kill anyone with a military or a police uniform. The cartel also attacked civilian populations and journalists.” A journalist from Guerrero concurred: “[Cartels] kill local journalists to elevate the costs of the military intervention” and “to signal to the state that, if the armed forces don’t back off, their private militias are ready to kill anyone, just as they did with a journalist.” They kill journalists to deter military interventions in their turf.

Second, cartels attack the press more directly when journalistic reports affect the local balance of power in the criminal underworld, particularly following the decapitation of their group. A former colleague of Javier Valdez, the iconic local editor of Ríodoce in Sinaloa who was assassinated in 2018, recalled that Valdez’s murder took place in the midst of a bitter internal leadership conflict, following the arrests of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán in 2014 and 2016. Ríodoce had published an interview with Dámaso López—a former commander of the Sinaloa judicial police who had become one of the Sinaloa Cartel’s leading sicarios and a contender against the Chapitos, El Chapo’s children—that infuriated his enemies. Subsequently, Valdez penned a series of articles about the López clan, in which he quoted anonymous cartel members saying that Dámaso’s son “was good for socializing but not for business, let alone to succeed his dad or El Chapo” (Valdez Reference Valdez2017). A week after the article’s publication, a group of sicarios under López Jr.’s command brutally murdered Valdez. As one of them confessed: “We had to kill the journalist from Culiacán because he had published something that the bosses from Eldorado [López Jr.’s place of residence] did not like” (Proceso 2018). They murdered Valdez to punish him for publishing compromising information but also to signal López Jr.’s resolve to kill in order to survive in war.

Third, cartels and their lieutenants attack the press when journalists disclose information about war developments that can render them vulnerable to their rivals. A journalist from Jalisco explained that disclosing information about “recruitment houses where young men were trained into sicarios” was particularly sensitive, and a reporter from central Veracruz spoke about the risks of reporting about the “safe houses” that have proliferated in Mexico’s criminal wars, where criminal lords take refuge and where OCGs pile up their weapons and other illicit goods and where they keep people they abduct in the conflict. A photojournalist from Veracruz spoke about the high risk of reporting about “clandestine mass graves, where state security forces and armed groups” intentionally hide their enemies’ bodies.

Business survival. Participants across FGs noted heightened risks when they reported on armed conflicts over the control of illicit economies beyond drug trafficking. As a reporter from Jalisco put it, “these are fierce disputes for businesses, illicit rents, and territories.” Local journalists spoke about the dangers of reporting about “criminal taxation” (e.g., Jalisco, Michoacán, Veracruz, and Morelos); “land grabs and population displacement to control arable land and natural resources” (e.g., Chihuahua); and control of “convenience stores and supermarkets and basic supplies in towns and villages” (e.g., Guerrero and Morelos). A reporter from Morelos noted that “in the past, if you did not report on security issues or drug trafficking you faced few risks. But now it is different because you face major risks even when reporting on a social protest for water resources or against a mining company … or against the opening of a supermarket … . Any of these actions may be affecting the interest of the narcos.” A Guerrero reporter shared receiving threats when he reported that a large mining company in the city of Iguala paid criminal taxes. The veteran journalist from Sinaloa who described the assassination of Javier Valdez amid intra-cartel conflicts concluded that criminal lords and their subnational government partners kill journalists “to conceal corruption” and to safeguard the state-criminal complicit networks that give their participants access to extraordinary illicit rents in multiple illicit economies. Drug lords and government officials implicated in illicit economies care deeply about local reports. As a local journalist from Veracruz shared with Article-19 (2024), some days “the plaza chief asks about the content of the next day newspaper” but others it is “the police that want to know about the headlines or the frontpage photos.”

Political-criminal survival. Participants in FG2 and FG3 concurred that risks of attack for local journalists grow exponentially when OCGs, in collusion with subnational authorities, seek to de facto control local territories, illicit economies, people, and local governments. Establishing control over criminal taxation or the looting of natural resources often entails the use of high coercion and gross human rights violations to elicit compliance. Participants across groups consistently suggested that because elected officials face the gravest risks of political backlash and criminal prosecution, they are often the masterminds of attacks against the press but delegate operations to OCGs and their foot soldiers.

Patricia Mayorga, the distinguished local journalist who worked with the iconic journalist Miroslava Breach killed in 2018, reported that she and Miroslava were in great danger after they reported that the leader of the “Salazar” clan, a local ally of the Sinaloa Cartel, had appointed his closest relatives as party candidates for several municipalities in the Sierra Tarahumara in southern Chihuahua. Their report forced the parties to replace the candidates. The Salazars nonetheless were able to seize control over the municipalities and their police forces, displacing thousands of indigenous villagers from their land and monopolizing the looting of the forests and other natural resources. After Breach published articles showing how the Salazar clan had done this, the Salazar hitmen working with a local mayor killed her (Colectivo 23 de Marzo 2019). They did it, Mayorga says, to silence Miroslava and the press in the Tarahumara.

In a FG that only convened journalists from different parts of Veracruz, all participants agreed that the state’s major wave of assassinations of journalists began as local journalists started reporting on hundreds of clandestine mass graves, where subnational government officials and the Zetas disposed of the bodies of their enemies. Because local officials and the Zetas wanted to keep these atrocities away from the public eye, they were ready to silence anyone who dared to investigate disappearances. As a photojournalist from Veracruz observed, “the outbreak of the wave of disappearances and the proliferation of mass graves marked an inflection point for journalism in Veracruz; to this day those of us who report on [these topics] continue to face great dangers.”

Likely Perpetrators

In a context of widespread impunity, in which very little is known about the perpetrators of lethal attacks against the press, the journalists’ voices represent crucial information. FG participants and participants in in-depth interviews were unanimous about the likely perpetrators of attacks. A journalist from northern Guerrero aptly summarized the consensus: “[Subnational] government officials and drug cartels murder journalists.” Local journalists from nine states named governors, state attorneys, secretaries of public security, state police chiefs, and mayors and their police chiefs as directly responsible for the killings. Others named specific cartels, drug lords, and their private militias. Whether motivated by self-preservation in war or by business or political-criminal survival, all of them insisted that public officials and OCGs often acted jointly in silencing the press.

Several influential investigations support the FG consensus about state-criminal collusion in the assassination of local journalists (refer to online appendix IX). A path-breaking “macro-criminality” study of the assassination of 20 local journalists in Veracruz during the administration of Governor Javier Duarte (2010–2016) concludes that there are strong indications of the likely collusion of subnational government officials and OCGs in silencing the press (Article-19 2024). The study suggests that Governor Duarte and his Secretary of Public Security and the secretary’s special police forces, the state’s Attorney General and the judicial police, and mayors and their police forces, in collusion with the Zetas or the New Generation Jalisco Cartel (CJNG), dominated illicit economies and were possibly implicated in the attacks against local journalists for publishing unwanted information. An award-winning investigation of the assassination of Veracruz journalist Regina Martínez concludes that when Martínez was murdered, one colleague confirmed that she had been investigating a former state attorney general’s business partnership with the Zetas, the former private militia of the Gulf Cartel, in the operation of the retail drug trade in Veracruz’s capital city (Corcoran Reference Corcoran2022). A major investigation by a multinational consortium of journalists prompted a Chihuahua court to sentence a mayor and a local cartel’s chief of sicarios for the concerted assassination of Miroslava Breach (Colectivo 23 de Marzo 2019).

Macro Outcomes: Silencing Society

In all FGs participants suggested that in exercising criminal governance, subnational authorities and criminal lords seek to create “silence zones” in which local fine-grained information remains private and is prevented from reaching the public arena. As our FG participants from Veracruz shared, in 2015 Moisés Sánchez, the highly respected director of the town-level news outlet La Unión: La Voz de Medellín, was assassinated for exposing deep corruption by the Medellín mayor—a municipality co-governed by drug cartels and the state governor, where the mayor enjoyed absolute impunity to kill (Article-19 2024). Because local journalists like Sánchez are high-profile public figures in their localities, their assassination is intended to instill “fear,” “terror,” and a social “psychosis” that paralyzes local societies and precludes resistance to criminal governance. As Ibarra’s (Reference Ibarra2023) influential investigation shows, local journalists are victimized not only for exposing but for publicly defying injustices, corruption and power abuse, and for demanding an end to impunity. This is consistent with Hughes and Márquez Ramírez’s (Reference Hughes and Ramírez2018) important finding that journalists facing the most severe risks of attacks are those who believe that their role is to oversee power and support social change.Footnote 11

Conclusion