Believe in something, even if it means sacrificing everything.

—Colin Kaepernick for Nike’s “Just Do It” advertisement campaign

Black celebrity activism has a long tradition in American politics. Black actors, artists, musicians, and athletes are said to have a responsibility to use their celebrity platforms to raise the voice and concerns of black people (e.g., Raymond Reference Raymond2015). Some of the most notable examples are black sports activists who used athletics and the playing field to challenge the racist norms of US society. In 1960, three-time Olympic gold medalist Wilma Rudolph declined to attend a celebration in her honor because the event would be segregated. Muhammad Ali refused to enlist in the US Army in 1967 in objection to Vietnam, famously saying, “No Vietcong ever called [him] nigger.” John Carlos and Tommie Smith stood as medal winners on the podium at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico and raised their black-gloved fists in a salute to Black Power as the US national anthem played.

More recently, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement has spawned a new generation of sporting celebrities protesting state violence against black Americans. Players with the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) led pre-game protests in 2016, and later that year, four of the top players from the National Basketball Association (NBA), including LeBron James of the Cleveland Cavaliers, opened the ESPY awards show by addressing the killing of unarmed black people by the police. Also, in 2016, former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick stirred controversy when he and teammate Eric Reid chose to kneel on the sideline during the singing of the national anthem to protest the dramatic killing of unarmed black men by police in American cities like Baltimore and New York, ostensibly in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement (Branch Reference Branch2017).

But, for all that controversy, little attention has been given to the influence of these black athlete activists, or sporting celebrities, on black political action. Although various models account for racial differences in political behavior between black and white Americans—often suggesting black political elites have the potential to empower individual blacks (Dawson Reference Dawson1995; Harris-Lacewell Reference Harris-Lacewell2006), none examine black celebrity activists as a mobilizing force. Although studies on celebrity have shown professional actors, athletes, and artists do have a noticeable influence on a variety of outcomes (Austin et al. Reference Austin, Van de Vord, Pinkleton and Epstein2008; Becker Reference Becker2012, Reference Becker2013), few have thoroughly tested the impact of celebrity on political behavior in general, and much of the existing research has yielded mixed results related to electoral participation. Moreover, sport celebrities “have not generated the same interest as celebrities within the realms of music, film, art, or politics” (Andrews and Jackson Reference Andrews and Jackson2002, 7).

In this article, we argue that accounting for the influence of a specific type of celebrity, black athlete activists, and their influence on a specific audience, black Americans, offers a clear demonstration of the influence that celebrity has on politics. Because sport fans possess or develop affective attachments to sport celebrities, we claim black sport stars who engage in political protest are especially well positioned to influence racial in-group members for at least two reasons: they are credible in-group messengers engaged in issue-congruent activism—that rooted in exposing racial grievances of the group—and their protest action often results in professional consequences. To understand these dynamics, we consider the protest activity of Colin Kaepernick to examine what, if any, influence he has had on contemporary black political engagement (for more on the critical nature of black mobilization, see Chinni Reference Chinni2018). We expand our analysis of political engagement beyond voting to include protest and other modes of political expression because black athletes often encourage protest, boycotts, or action outside of the realm of traditional politics (for a discussion of subtle effects, see Pease and Brewer Reference Pease and Brewer2008).

We first introduce a definition of celebrity that focuses attention on the protest activities of black sport stars. Then, we consider the broader effects of celebrity on economic outcomes, social behaviors, and politics. Next, we describe the protest actions of black sport stars during the Black Power movement as a gateway to our discussion of contemporary cases of black sport activism, foreshadowing our expectations about Colin Kaepernick. The final sections describe the survey data we use to test our expectations and present the findings. The results suggest the protest activity of Colin Kaepernick significantly influences black political action, specifically encouraging action beyond voting, and hint at the influence that he, among other black celebrities, could have potential as a movement leader. We conclude with a discussion of celebrity, sport culture, and race.

Celebrity, Sport, and Politics

The sport industry is a powerful forum for celebrity. The average per game attendance of the five major sport leagues exceeds twenty thousand fans, with the National Football League attracting the highest attendance. Despite the volume of this attention and the claim contemporary celebrities are most likely to emerge from the entertainment or sport industries (Turner Reference Turner2004), not all professional athletes are celebrities. According to Rojek’s (Reference Rojek2001) description of celebrity, Colin Kaepernick may have achieved celebrity in terms of his rank among competitors, but he was not well-known for his “well-knownness” in the way Boorstin (Reference Boorstin2012, 221) conceived of celebrity. Both descriptions highlight the difficulty in defining celebrity: the fleeting nature of fame, as popularized by artist Andy Warhol’s observation that everyone would be “world-famous for fifteen minutes.” Thus, Rojek (Reference Rojek2001), Giles (Reference Giles2000), and Drake and Miah (Reference Drake and Miah2010) correctly emphasize the mediated production of celebrity (e.g., through social media).

Although informative, none of these definitions of celebrity is entirely satisfactory for our purposes. Not even the specific characterization of sporting celebrities as the “product of commercial culture, imbued with symbolic values, which seek to stimulate desire and identification among the consuming populace” adequately captures the unique relationship between sports, politics, and athlete activism for black America (Andrews and Jackson Reference Andrews and Jackson2002). Therefore, to examine the importance of the black athlete activist as a celebrity, we draw on Street’s (Reference Street2004, 438) description of the celebrity politician as an “entertainer who pronounces on politics and claims the right to represent…causes, but who does so without seeking…elected office.” This view of celebrity provides an important context for understanding black athlete activists, or, black sport stars, as celebrity politicians. In addition, this definition best captures celebrities’ ability to engage in public gestures similar to the political protest engaged in by the black sport stars whom we are interested in here (Andrews and Jackson Reference Andrews and Jackson2002; Bryant Reference Bryant2018; Jackson Reference Jackson2014; Miller and Wiggins Reference Miller and Kenneth Wiggins.2004).

Much of what we know about the effects of celebrity is concerned with the economic value of celebrity endorsements, specifically whether contracting celebrity endorsements pays off (Agrawal and Kamakura Reference Agrawal and Kamakura1995; Erdogan Reference Erdogan1999). Several studies indicate the return on investment (ROI) is positive and substantial: celebrity endorsements yield increases in sales, stock returns, and brand credibility (Chung, Derdenger, and Srinivasan Reference Chung, Derdenger and Srinivasan2013; Elberse and Verleun Reference Elberse and Verleun2012; Silvera and Austad Reference Silvera and Austad.2004), with one in five ads around the world featuring a celebrity (Halonen-Knight and Hurmerinta Reference Halonen-Knight and Hurmerinta2010). Commercial brands therefore have an incentive to cut ties with controversial celebrities, because negative information from a celebrity endorsement can facilitate the negative transference of affect to the brand (Sanderson, Frederick, and Stocz Reference Sanderson, Frederick and Stocz2016; White, Goddard, and Wilbur Reference White, Goddard and Wilbur.2009). This explains why many were surprised by the decision of the sport apparel company, Nike, to name in early September 2018 the former San Francisco 49ers quarterback as one of the faces for its 30th anniversary “Just Do It” campaign. Almost immediately, angry, mostly white, customers went to social media to broadcast themselves live destroying the Nike apparel they owned. Even the president of the United States took to Twitter to admonish the company: “What was Nike thinking?” he asked.

This brings us to the question of celebrity and politics, for which there are two possible approaches. One is to consider celebrities as emergent politicians, advocates, and activists. This line of inquiry focuses on sport and celebrity diplomacy, for instance, and considers the role—or folly—of celebrity ascendance across domains (Brockington and Henson Reference Brockington and Henson2015; Hoberman Reference Hoberman1977; Huliaras and Tzifakis Reference Huliaras and Tzifakis2010; Lines Reference Lines2001; Majic Reference Majic2018; Nygård and Gates Reference Nygård and Scott2013; Strenk Reference Strenk1979). The second approach, which we take, is to examine the effects of celebrity on public attitudes and mass behavior. One notable example is Garthwaite and Moore’s (Reference Garthwaite and Moore2013) finding that Oprah’s endorsement of then-presidential candidate Barack Obama yielded an additional one million voters in the 2008 Democratic presidential primary. However, the influence of a mononymous celebrity of such acclaim, like Oprah, may be an outlier. The literature suggests young adults are not only more likely to be politically influenced by friends and family than by celebrities (O’Regan Reference O’Regan2014) but also that celebrities tend to exert the greatest influence on self-efficacy, involvement, and complacency (Austin et al. Reference Austin, Van de Vord, Pinkleton and Epstein2008; Becker Reference Becker2013, Reference Becker2012).

Additional research has suggested that accounting for the extent to which individuals identify with celebrities, as well as the celebrities’ credibility in terms of issue congruence, may reveal more about their influence (Basil Reference Basil1996; Fraser and Brown Reference Fraser and Brown2002). Therefore, if sport fans possess or develop affective attachments to sport celebrities, as some contend, and the public considers celebrities more credible and trustworthy than politicians (Frizzell Reference Frizzell2011), then black sport stars engaged in issue-congruent protest should be well positioned to influence racial in-group members (McClerking, Laird, and Block Reference McClerking, Laird and Block2018).

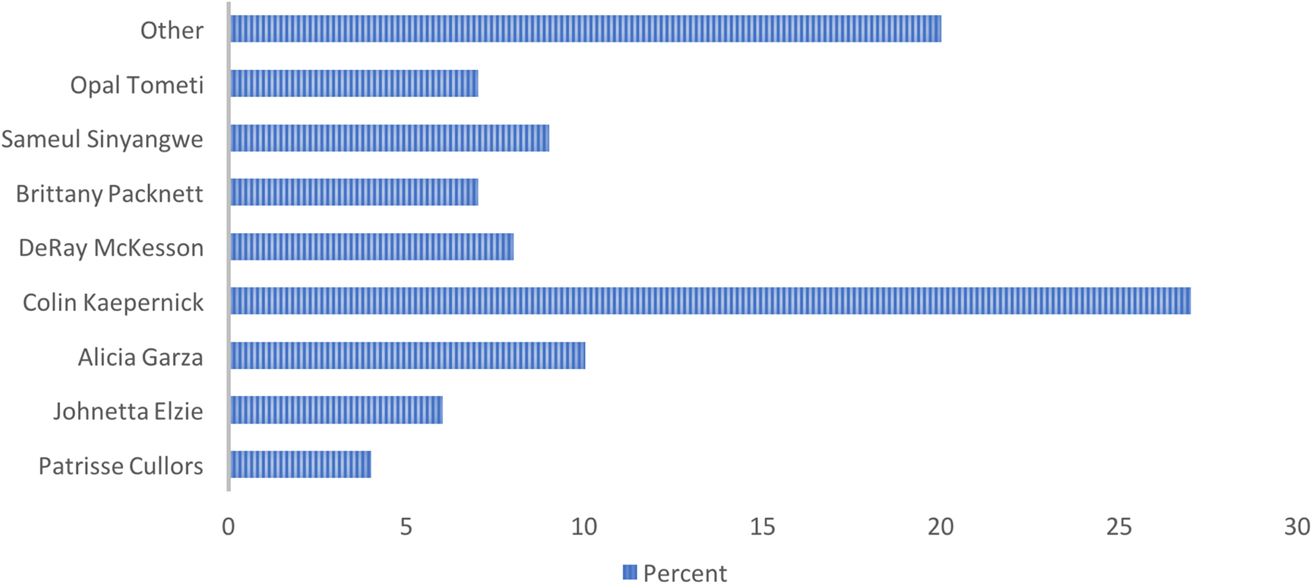

There may be many reasons for the potential influence of black sport stars, but at its core, it may reflect the tendency of black sporting celebrities to engage in race-based protest politics that complement ongoing social movements, such as Black Power or Black Lives Matter, in their efforts to spotlight the unfavorable political, social, and economic condition of black Americans (Leonard and King Reference Leonard and King2009; Raymond Reference Raymond2015). For example, as figure 1 shows, black Americans believe Colin Kaepernick’s protests were an effort to bring attention to police violence, and nearly 80% supported him and other players protesting the national anthem (Intravia, Piquero, and Piquero Reference Intravia, Piquero and Piquero2018). High media visibility or the potential thereof, in addition to political controversy and backlash, may make black athlete activists an ideal source for social and political messaging (see, e.g., Kuklinski and Hurley Reference Kuklinski and Hurley1994). Consider that more than one-quarter of black Americans identified Colin Kaepernick as their top choice to lead the National BLM Movement, ahead of the movement’s cofounders Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi (figure 2).Footnote 1

Figure 1 Attitudes about national anthem protests by race and question wording (source: Baker Reference Baker2018)

Figure 2 Respondents’ top choice to lead a national BLM movement (Reference TilleryTillery n.d.)

Therefore, there are at least two factors fundamental to our understanding of black celebrity athlete activists: the use of celebrity to represent black causes without seeking political office and their ability to appeal to the black community, and often America at large, because of the capital their fame allows them to wield. In addition to the well-documented power of racial group identity—including group-based protection, affect, and receptivity to messengers of the same racial in-group (Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996; Dawson Reference Dawson1995; Huddy Reference Huddy, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013; Tate Reference Tate1994), there is reason to believe that black celebrity activists can have a politically empowering influence on black Americans (for discussion, see Meyer Reference Meyer1995).

Rebellion and Punishment: The Black Athlete Activist as Celebrity Politician

Black sport stars engaged in activism in the athletic arena have long recognized sports as a useful political tool to gain prestige and protest (Strenk Reference Strenk1979). Athletic protests are appealing to black athlete activists because sports are organizational and group based, and black athletes are often well represented among successful athletic competitors (Hartmann Reference Hartmann2003), providing them with the resources to engage in various forms of sports activism (Cooper, Macaulay, and Rodriguez Reference Cooper, Macaulay and Rodriguez2017; Meyer Reference Meyer1995). Moreover, the role of black sport star activism is decidedly different from that of other celebrities, because the athletes’ goal is seldom to shift the movement of which they are a part toward “consensus-style politics,” as Meyer (Reference Meyer1995, 191) contends other celebrities do.

In 1968, for example, during the burgeoning Black Power movement, Harry Edwards helped organize the Olympic Project for Human Rights Protest (OPHR). This effort used the Summer Olympics that year to protest racism and the poverty that affected black communities throughout the United States. The most notable gesture, as mentioned, came from Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who both protested by raising their black-gloved fists as they were standing on the medal stand while the US national anthem played. In the summer of 1967, three black players of the NFL’s Cleveland Browns, including Walter Beach, were interviewed by the Cleveland Plain Dealer about the Hough revolts in Cleveland the previous summer. These demonstrations were led by blacks who felt disenfranchised by limited job opportunities and segregation in the city and resulted in millions of dollars in destruction. Beach said he “sympathize[d] with the residents of Hough, knowing their content and the causes” (Bennett Reference Bennett2013, 176)

Many black athlete activists engaged in individual and collective protest, especially at the collegiate level throughout the 1960s.Footnote 2 With their involvement spanning both college and professional sports in the 1970s and 1980s, there was a shift from ‘shut up and play’ to athlete-activist (Moore Reference Moore2017); many, Edwards (Reference Edwards2017, 38) contends, arrived “in the arena as warriors in the struggle for black dignity and freedom.”

However, what is also important is the extent to which these “revolting black athletes” were threatened with banishment from sports, incarceration, and even death if they used their celebrity capital to challenge white supremacy. Mohammed Ali was unable to box from 1967 to 1970, because no state would give him a license following his refusal to enlist in the army; John Carlos and Tommie Smith were stripped of their gold medals shortly after the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico; and Art Modell, owner of the Cleveland Browns, chided Walter Beach for his comments to Cleveland’s Plain Dealer about the Hough demonstrations and warned him to focus on football rather than social problems (Parrish Reference Parrish1971; Suchma Reference Suchma2005). Beach said he “had a lot of difficulty in football” from that point on; the following summer, the Browns placed and then illegally removed Beach from the waivers list (Bennett Reference Bennett2013, 176). He never again played in the NFL.Footnote 3

That black athlete-activists have often suffered professional consequences for their protest reminds black Americans of the ways in which the white power structures threaten to punish outspoken and esteemed members of their racial in-group. For example, Muhammad Ali’s refusal to enlist in the US Army ignited a sequence of consequential events: the revocation of his passport, the denial of his boxing license, and the forfeiture of his heavyweight boxing title. More recent threats of similar professional penalties for Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling became explicit during a political rally in Huntsville, Alabama, in September 2017 when President Trump foretold the quarterback’s professional fate:

Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, “Get that son of a bitch off the field right now. Out! He’s fired. He’s fired!” You know, some owner is going to do that. He’s going to say, “That guy that disrespects our flag, he’s fired.” And that owner, they don’t know it, they’ll be the most popular person in this country.

Indeed, the NFL league owners took note: Kaepernick was shut out from playing in the NFL the following season. In response, he filed a legal complaint against the league, alleging that teams colluded to deny him employment opportunities because of “his leadership and advocacy for equality and social justice” (Kaepernick v. National Football League, 2017).

Because of the collective identity their protests represent, close consideration of black sport celebrities engaged in activism may refine models of minority political participation. The case of Colin Kaepernick is instructive because his silent protest was anchored in racial solidarity against police violence, and like the experience of Walter Beach and others, after Kaepernick’s contract expired, no other NFL team signed him. His experience may remind black Americans of the ways in which white power structures punish outspoken black celebrities and mobilize in response (Crawford Reference Crawford2018; Hodge et al. Reference Hodge, Burden, Robinson and Bennett2008; Musgrove Reference Musgrove2012; Nunnally Reference Nunnally2012; Warner Reference Warner1977). Kaepernick’s position as a claimant in a lawsuit against the NFL suggests he was harmed by an unfair action taken by the league, which is important insofar as others have argued that the black community mobilizes around controversial black public figures who, they suspect, have been targeted, retaliated against, or harassed by white-dominated institutions in realms such as sports, media, and law enforcement (Russell-Brown Reference Russell-Brown2005).

Black Americans also understood Kaepernick’s protests to be an effort to spotlight American racism and police brutality, which helps explain their overwhelming support, as shown in figure 1, for his and other players’ protests of the national anthem (Intravia et al. Reference Intravia, Piquero and Piquero2018).Footnote 4 Moreover, it is not only the masses of blacks who remain steadfast supporters of Kaepernick; a poll of defensive players from 25 NFL teams revealed that 95% believed Kaepernick “belonged” on an NFL roster (Chiari Reference Chiari2019). The “intensity and ferocity of mainstream American opposition to the demonstration[s]” (Hartmann Reference Hartmann1996, 557) of black sport stars may not be as surprising as it is revealing.

The Case for Colin Kaepernick

The context for the sport activism of Colin Kaepernick was the killing of unarmed black men by police in US cities, including New York City, Baltimore, and Ferguson, Missouri, a suburb of St. Louis. During a preseason game in August 2016 in which Kaepernick was starting, he chose to kneel on the sideline during the national anthem in protest, along with his teammate Eric Reid, which sparked a national debate (Branch Reference Branch2017). Even though other black sport stars were similarly engaged in grassroots activism in response to police brutality (Cooper, Macaulay, and Rodriguez Reference Cooper, Macaulay and Rodriguez2017; Gill Reference Gill2016), the backlash was immediate, and the ire focused almost entirely on Kaepernick.Footnote 5

We focus on the former 49ers quarterback for several reasons. With the aid and abetting of national and social media, the public came to recognize Colin Kaepernick as the celebrity leader of the BLM movement (see figure 1). Second, he is the only athlete in his protest cohort to remain ousted from the profession for his protest action; he also sued the NFL for alleged collusion to deny him professional opportunities on a team. Third, the NFL settled Kaepernick’s lawsuit, giving him damages for collusion. These factors make Kaepernick the most compelling case to search for a relationship between support for celebrity protest action and political engagement at the individual level.

Empowerment by Social Movement: Hypothesis 1

To understand Kaepernick’s political influence, his protest actions must be placed in the broader context of the protest movement he has come to represent: Blacks Lives Matter (BLM), the most prominent campaigner against state-sanctioned violence and racism toward black people (for discussion, see Meyer Reference Meyer1995). Group-based models of politics emphasize the influence of racial group identity on group norms, behavior, and a sense of linked fate (Dawson Reference Dawson1995; Whitby Reference Whitby2007; White, Laird, and Allen Reference White, Laird and Allen2014). Blacks have found great success mobilizing through organizational, group-based resources like the black church, the institutional backbone of black civic engagement. Today, new technologies have allowed different organizational, group-based resources to emerge, enabling movements like BLM in particular to build a powerful grassroots digital presence that can leverage media and Kaepernick’s celebrity voice (Stephen Reference Stephen2014).Footnote 6 Therefore, because group-based models suggest racial group identity is a powerful mobilizer (Dawson Reference Dawson1995), the BLM movement may heighten blacks’ sense of solidarity and ignite group mobilization (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Gurin, Gurin and Malanchuk1981), we offer the following hypothesis:

H1: When considering group-based resources (i.e., racial group identity and the BLM movement), we do not expect that approval of Kaepernick’s protests will independently influence black political mobilization.

Empowerment by Black Athlete Activists: Colin Kaepernick Support Hypotheses

The emergence of a black athlete activists like Colin Kaepernick may nonetheless have an empowering celebrity-elite influence as blacks move between protest and politics (Stout and Tate Reference Stout and Tate2013; Tate Reference Tate1991). Attention to black political empowerment was resurgent but short-lived following the election of Barack Obama as president. At its core, questions of empowerment seized on the familiar puzzle of descriptive representation and its effects on feelings of linked fate, black turnout, trust, and efficacy (e.g., Gilliam and Kaufmann Reference Gilliam and Kaufmann1998). However, highly mediated incidents of racial violence across the country caused an outcry and ignited a social movement, including BLM, which reinforced the view that Obama’s presidency was yet another hollow prize for black representation.

In addition, President Trump’s taste for controversy, aggrandizement, and bold pronouncements of law and order while using explicit racist, sexist, and Islamophobic language raises serious threats to already vulnerable communities; recent research directly connects opposition to Trump, which is characterized by perceptions of racism, to significantly higher levels of political interest and engagement (Towler and Parker Reference Towler and Parker2018). Thus, although BLM’s use of online organizing may be limiting the power of the movement to urge blacks to act—research suggests face-to-face contact is the strongest mobilizer (Gerber and Green Reference Gerber and Green2000)—we believe that the organizational network, specifically its built-in-leaders, such as Kaepernick, represent a mobilizing elite. Moreover, if our theory is correct, Kaepernick should serve as a celebrity figure who compels blacks already identifying with BLM to feel empowered and engage in politics.

In general, we expect attachment to the broader BLM movement will offer blacks a positive reason to engage in politics. We also expect Colin Kaepernick, acting as a black celebrity leader, will further empower blacks, compelling them to act. On the other hand, if approval for Kaepernick’s protest is simply a symptom of group-based politics, blacks who support Kaepernick will not participate in politics any differently from blacks who are less approving once BLM identity is considered. However, if, as we posit, approval for Kaepernick’s protest offers additional motivation beyond traditional factors associated with group-based mobilization, blacks who strongly approve of Kaepernick’s protest will engage at higher rates than others, because Kaepernick’s celebrity protest represents something more to them. Moreover, the influence of Kaepernick approval should only elevate the political action of blacks who also already identify with the Black Lives Matter movement. This leads to our final two hypotheses:

H2: Blacks who strongly approve of Kaepernick’s protest action are significantly more likely to engage in politics even after accounting for linked fate and Black Lives Matter identity.

H3: Black attitudes toward Kaepernick moderate the relationship between Black Lives Matter identity and political engagement, such that blacks who report strong BLM identity and strong approval for Kaepernick’s protest action are the most engaged.

Data, Methods, and Analysis

To test our hypotheses regarding the relationship between Kaepernick approval and political engagement, we turned to the 2017 Black Voter Project (BVP) Pilot Study. The 2017 BVP Pilot Study is an original dataset that we created in the months following the 2016 election. The sample is comprised of 511 black respondents located in six battleground states first identified in the 2011 Multi-State Survey of Race and Politics, all with significant black constituenciesFootnote 7—Georgia, Michigan, Missouri, Ohio, North Carolina and Virginia—as well as the state of California.Footnote 8 Data were collected from March through April 2017, in states where black turnout could potentially swing an election (California was included for comparison). Because of concerns regarding low black mobilization during the 2016 general election, with reports suggesting that black turnout dropped as much as 12% in some battleground states, a focused analysis proves useful in understanding ways to increase the potential political power of black constituencies (Fraga et al. Reference Fraga, McElwee, Rhodes and Schaffner2017; Gillespie and King-Meadows Reference Gillespie and King-Meadows2014). Focusing on battleground states allows conclusions to be drawn about mobilization in black populations instrumental to federal election outcomes. However, although they are informative, these results cannot be generalized to blacks across the entire country.Footnote 9

We rely on two proxies in the BVP Pilot Study to assess support for Colin Kaepernick and the celebrity-driven protest movement with which he has been associated. Respondents were asked, “Based on what you have heard, do you approve or disapprove of Colin Kaepernick’s and other NFL players national anthem protests?” To isolate blacks who expressed the most support for Kaepernick and preserve as much variance as possible in a measure with little disagreement, we coded approval of Kaepernick on a dichotomous scale (0–1), where high values correspond to strong approval of Colin Kaepernick’s protest. To examine the conditional effect of Kaepernick approval on attachment to the broader Blacks Lives Matter movement, we probed respondents’ attitudes toward it: “How closely do you identify with the Black Lives Matter movement?” This measure was coded on a three-point scale (0–1–2) such that higher values corresponded to respondents who identified more closely with the BLM movement.Footnote 10 If our claims are correct, not only will blacks who strongly approve of Kaepernick participate in politics at high rates but also those who strongly identify with BLM will participate in politics at higher rates than blacks who strongly identify with BLM but are not as approving of Kaepernick.

To examine political engagement, we assess whether blacks voted in 2016, their intention to vote in 2018, and their participation in several other political behaviors that go beyond voting, such as signing a petition, boycotting, demonstrating, attending a political meeting, contacting their representative(s), and donating to a political campaign. Although the utility of voting is central to research in political science, recent work suggests that nontraditional political acts beyond voting significantly predict how closely a representative’s actual roll-call vote record aligns with community interests (Leighley and Oser Reference Leighley and Oser.2018). Both voting in 2016 and vote confidence for 2018 were coded on dichotomous scales (0–1), where 0=blacks who did not vote in 2016 and were not confident that they would vote in 2018 and 1=blacks who voted in 2016 or blacks who expressed certainty that they would vote in the 2018 midterm elections. Each political act beyond our measures of voting was coded on a dichotomous scale (0–1) such that 1=participation in such an act within the last 12 months. Specifically measuring political action within the last 12 months eliminates the possibility that our models capture a relationship between political engagement earlier in life and attitudes toward Kaepernick. Moreover, any political participation in the 12 months before the survey would also have occurred after Colin Kaepernick’s protest action became national news, suggesting that the protest action we are measuring occurred at least during (or after) the time his protest was taking place.

In an ideal setting, longitudinal data would allow for a clear understanding of the directional relationship between support for Kaepernick and political engagement; the cross-sectional nature of our data, however, limits our ability to say with certainty whether support for Kaepernick leads to engagement, or vice versa. Still, modeling political engagement in a multiple regression setting allows us to account for other factors associated with a politically active lifestyle, such as political interest and political knowledge. If our results hold in the multivariate setting, we can state with confidence that our proxy for Kaepernick approval is measuring something more than a selection bias. Moreover, additional model specifications (available on request) account for political action sometime in life prior to the last 12 months, which provides additional evidence that the political action we are measuring in the last 12 months is associated with attitudes toward Kaepernick, rather than being a reflection of past political tendencies.Footnote 11

In addition to identification with the BLM movement and support for Kaepernick, we account for several other sociodemographic and political factors that might also be associated with political engagement, including political interest, political knowledge (an index of questions about congressional representation, the vice president, and Supreme Court justices), ideology, and political trust (refer to the online appendix for a full list of variables and coding). Furthermore, earlier research suggests that factors associated with group-based resources are particularly important when examining black political participation. Hence, identity with BLM must be accounted for, along with church participation and broader racial group identity (linked fate), if any significant differences in black political action are to be uniquely associated with Kaepernick’s celebrity.

Black Political Participation: Results and Analysis

Current and historical research on black political participation suggests that group-based resources, along with political and sociodemographic factors, generally explain black political participation. This study assesses whether Colin Kaepernick’s celebrity galvanized black supporters even further, leading to significantly heightened levels of political action. Although Colin Kaepernick is relaying much of the same messages found in many sectors of the black community, such as the BLM movement, does Kaepernick’s celebrity leadership move blacks enough to evoke political engagement?

Before we examine the relationship between support for Kaepernick and political participation, it would be helpful to establish the link between support for his celebrity protests and the BLM movement itself. Although Kaepernick credits the BLM movement for much of his perspective and activism, do blacks who support BLM recognize the same link? Table 1 presents the bivariate relationship between BLM identity and Kaepernick approval and suggests that they do. A full 71% of blacks who strongly identify with BLM also express strong approval for Kaepernick, compared to only 44% of those with weak BLM identity.

Table 1 Approval of Kaepernick’s protest by strength of BLM identity

Note: Relationship significant at χFootnote 2<0.05.

Moreover, the two measures are correlated at 0.23, suggesting they are related within the data of black individual attitudes. This basic relationship not only offers validation for Kaepernick’s anecdotal association with the BLM movement at the individual level but also highlights the need to examine blacks’ support for Kaepernick as it relates to identity with the BLM movement; history suggests that celebrity leaders who emerge from the sports industry often join in an already ongoing social protest.

As we begin to examine the association between support for Kaepernick and black political behavior, our results offer mixed support for our claim that strong BLM identity and approval for Kaepernick are related to political action. Tables 2 and 3 present the bivariate relationship between BLM identity, approval for Colin Kaepernick, and black political engagement.

Table 2 Traditional political participation by Kaepernick approval and strength of BLM identity

Note: Relationship between traditional political participation and BLM ID significant at χFootnote 2< 0.05.

Table 3 Extra-traditional political participation by Kaepernick approval and strength of BLM identity

* Relationships significant at * χ2< 0.10.

At the bivariate level, we find a significant relationship between strong BLM identity and black voter participation as it pertains to turnout in the 2016 general election and confidence that one would vote in the 2018 midterm elections. Yet, support for Kaepernick fails to significantly define blacks who voted in 2016 or who identify as confident voters in the 2018 midterm election. For instance, in the case of turnout in the 2016 general election, 12 percentage points separate the proportion of blacks who strongly identify with BLM from those with a weak attachment, and a 17-point gap separate blacks who strongly identify with BLM for those who express confidence that they would vote in 2018. There is a similar proportion of 2016 voters and of confident 2018 voters who approve of Kaepernick’s protest. Although this may seem surprising, revisiting Kaepernick’s personal politics suggests his influence as a political leader may not be intended for the traditional task of voting. In a November 2016 interview, Kaepernick expressed disgust for both Republicans and Democrats as he explained why he did not cast a vote in the 2016 election (Brinson Reference Brinson2016). Although his decision not to vote garnered much criticism, it does offer some explanation as to why his celebrity leadership may not be associated with black voting behavior.

Therefore, at the bivariate level, how some blacks feel about BLM is significantly associated with voter participation, whereas Kaepernick approval is not. These patterns only hold if we limit political participation to voting. Table 3 displays the bivariate relationship between both Kaepernick approval and BLM identity, and political participation beyond voting.

According to table 3, at least a 20-point gap separates the proportion of blacks who strongly approve of Kaepernick from those who do not when it comes to both signing a petition and participating in a boycott. When it comes to participating in a political demonstration, attending a political meeting, contacting one’s representative, or donating to a political campaign (or cause), at least a 10-point gap separates blacks who strongly approve of Kaepernick from all others. Although less pronounced, similar differences characterize the relationship between BLM identity and political participation beyond voting. Thus, our bivariate results suggest there is a significant association between the way blacks perceive their identity with BLM and their voting behavior, whereas both BLM identity and Kaepernick approval are significantly associated with other political acts beyond voting. Moreover, considering the correlation between BLM identity and Kaepernick support, along with Kaepernick’s indirect connection to the BLM movement at large, we believe that attitudes toward Kaepernick—as a celebrity leader of the movement against police brutality— also moderate the relationship between BLM identity and political engagement. In the next section we present a more rigorous multiple regression analysis to further test these claims.

Multiple Regression Analysis

The next step is to account for alternative explanations when examining the relationship between approval of Colin Kaepernick and political participation, both as expressed in voting and beyond. We engaged in multiple variable regression modeling to account for ideology, partisanship, political knowledge, political interest, political mistrust, approval of former president Obama, and racial group identity (or linked fate), along with various sociodemographic and political measures. At first glance, the bivariate results hold even after accounting for an overabundance of additional factors (refer to tables A1 and A2). Table 4 displays the predicted probability of a black respondent engaging in politics based first on BLM identity and then on their approval of Kaepernick.

Table 4 Change in predicted probability: traditional political participation

* Relationships significant at χ2< 0.05, one-tailed test.

After accounting for other factors, the differences between black approval of Kaepernick and voter turnout remains insignificant (refer to table A1). In other words, variables such as political interest, college education, and BLM identity account for differences in black voting behavior. Moving from a low to high identity with BLM predicts a 9% increase in the likelihood of voting in 2016 and a 12% increase in the likelihood of expressing confidence they would vote in 2018. In the case of voter turnout, identity with BLM, regardless of attitudes toward Kaepernick, predict blacks’ likelihood to vote.

However, when predicting political action beyond voting, strong approval of Kaepernick predicts significantly higher levels of political engagement across the board (refer to table A2). For instance, compared to blacks who do not express strong approval of Kaepernick, individuals who strongly approve are at least 10% more likely to have participated in politics beyond voting in the last 12 months and are 23% more likely to have participated in a boycott (table 5). Furthermore, BLM identity is only significantly associated with contacting one’s political representative. Therefore, support for Kaepernick is a more consistent predictor of nontraditional political engagement (beyond voting) than BLM identity, even after accounting for a host of alternative political explanations and measures of group-based resources.

Table 5 Change in predicted probability: extra-traditional political participation in last 12 months

* Relationships significant at χ2< 0.05, one-tailed test.

At the Intersection of Celebrity and Politics: Kaepernick as a Moderating Force

Our results suggest that, although approval for Kaepernick’s protest is strongly related to BLM identity, each works differently when examining black political behavior. Whereas strong BLM identity is significantly associated with voting, approval for Kaepernick’s celebrity protest movement is significantly associated with other political action such as signing a petition and participating in a boycott. However, attitudes toward Kaepernick may also moderate the relationship between BLM identity and political behavior. Put another way, are blacks who strongly approve of Kaepernick and the BLM movement even more likely to vote, participate in politics in other ways, or both? Thus, this final section explores the moderating effect, if any, that Kaepernick may have on the relationship between BLM identity and political action. To examine whether attitudes toward Kaepernick moderate the power of BLM identity, we constructed an interaction term and added it to our previous model specification (see, e.g., Block Reference Block2011).

A quick glance at the regression results suggests that either our base measures for BLM identity and Kaepernick approval, or the interaction measure, are significant depending on the political participation outcome (refer to tables A2 and A3). However, as many have previously pointed out, the statistical significance (or z-statistic) of a multiplicative interaction term does not indicate whether X has a statistically distinguishable relationship with Y at a particular value of Z (Ai and Norton Reference Ai and Norton2003; Berry, DeMeritt, and Esarey Reference Berry, DeMeritt and Esarey.2010; Brambor, Clark, and Golder Reference Brambor, Clark and Golder2006).Footnote 12 Considering the challenges that arise with correctly interpreting interactions terms, we explore the panels in figure 3, which depict the probability of voting and participating in politics in various ways, by BLM identity and Kaepernick approval.

Figure 3 Predicting traditional political engagement (conditional effects)

Figure 3 presents the probability of voting in 2016 and of expressing confidence in voting in 2018 by BLM identity and Kaepernick approval (refer to table A2). As BLM identity shifts from weak to strong, there is no significant difference in voting behavior between blacks who strongly approve of Kaepernick and those who are less favorable: Kaepernick approval fails to moderate the positive relationship between BLM identity and the likelihood of voting. However, strong approval of Colin Kaepernick elevates the likelihood of other actions above and beyond BLM identity. Figure 4 presents the probability of participating in six political acts: signing a petition, boycotting, demonstrating, attending a political meeting, contacting one’s representative, and donating to a political campaign, by BLM identity and Kaepernick approval (refer to table A3).Footnote 13

Figure 4 Predicting nontraditional political engagement (conditional effects)

With the exception of demonstrating, Kaepernick approval moderates the relationship between BLM identity and political participation in nonelectoral forms of action. (Considering the BLM movement is protest-based, it is not surprising that participating in a demonstration is one area where Kaepernick fails to move the needle beyond movement participation itself.) Moreover, among the nonvoting forms of political action, Kaepernick approval fails to differentiate levels of political participation among blacks with weak (low) identity with BLM, further solidifying our claim that Kaepernick’s role as a celebrity leader offers additional motivation for many blacks who already sympathize with the broader BLM movement.

Discussion

Activism by black professional athletes matters to black political action. Our findings reveal a relationship between the social protests of sport stars like Colin Kaepernick, the corresponding Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, and black political behavior. They generally suggest that black Americans who strongly approved of Colin Kaepernick and were highly identified with BLM were more likely to engage in several acts of nontraditional political engagement. These findings are important to the broader politics of celebrity in the sports industry, especially for what they tell us about the influence of black celebrity elites: our work demonstrates that this black celebrity interaction has the potential to mobilize black Americans to political action.

These results are consistent with other works on celebrity in politics. However, the case of Colin Kaepernick is unique because it allows us to reconsider the relationship between black celebrity activism and black politics. We agree with other scholars who suggest that the credibility of a celebrity and his or her issue congruence may be more important than celebrity itself. As such, our findings suggest that Kaepernick is a legitimate source of protest politics within black communities. In contrast, if Becker (Reference Becker2013) is right, and the public is more receptive to celebrity viewpoints on issues that are less politically salient, then black support for Kaepernick shows a meaningful congruence in the black public–elite interaction on issues typically outside of mainstream white politics: race and racism. One explanation is that black celebrity athletes are aware of threats to the racial group and therefore use their resources to advocate on its behalf.

Many black athlete activists have used their celebrity to call out social and economic injustice, often at great professional costs to their athletic careers. Yet, the political value of their activism is understudied. Our data provide initial evidence supporting the notion that professional athletes like Kaepernick may serve not only as national voices for justice but also as important links between social movements and heightened political engagement. Moreover, black activism that encourages nontraditional engagement beyond voting seems to be even more understudied, even though such actions have equally important political implications as voting.

As previously mentioned, Leighley and Oser (2017) find that the likelihood of issue congruence between constituents and their political representatives significantly increases when individuals participate in ways beyond voting, especially for lower-income individuals. Because this relationship is especially powerful for salient issues, and less-wealthy individuals are already prone to more policy incongruence with representatives, we believe black celebrity leadership like Kaepernick’s may in fact be instrumental to the long-term process of shifting public policy on one of the most salient issues across black America: police violence.

Furthermore, our findings show that approval for Kaepernick is uniquely powerful for blacks who already strongly identify with BLM, leaving us to wonder what influence he could have if he chose to take on an official leadership role in the movement. In addition, understanding Kaepernick as a link to political engagement is important, because underrepresented communities are currently instrumental to any democratic coalition looking for political success in an electorate facing historical polarization. Future studies should continue to explore the role and influence of black professional athletes on prosocial, economic, and political outcomes relevant to black communities, emphasizing the potential for celebrity leadership in an official capacity and examining behavior and attitudes over time.

Lastly, our study highlights a need for greater attention to these broader patterns of black elite–public interaction. The data from the 2017 Black Voter Project (BVP) Pilot Study are novel but also limited. For instance, panel data are ideal for understanding changes in political engagement over time, but no such data measuring black attitudes toward celebrity politics currently exist. Additionally, our dataset was limited to respondents from seven states, albeit states where blacks have a real chance of influencing electoral politics, limiting the generalizability of our results. Nonetheless, our results suggest a powerful relationship between support for Kaepernick’s protest action and black political engagement at the individual level, dynamics that are otherwise underexplored in the main of political science.

Conclusion

It would be easy to conceive of sports as simple social institutions that primarily organize and promote athletic competition, from T-ball to the Olympics. In thinking about sport culture, we often encounter this generalization, which introduces the familiar warning that politics is “out of bounds” in the athletic arena. But this view is at odds with our findings and is generally contradicted by a history in which sports are a regular exchange for nation-building and contentious politics, domestic and abroad. Still, the demand that black athletes “shut up and play” underlies an important question: What counts as acceptable politics in sports?

When the United States decided not to boycott the 1936 Olympic Games in Adolf Hitler’s Berlin as it began to confront the “ugly circumstances” of “Hitler’s anti-Semitic programs” (Kass Reference Kass1976), it placed Jesse Owens and other Olympians in the middle of a geopolitical ordeal that would break out in a world war three years later. But by many accounts, Owens’ achievement of winning four gold medals that year uprooted Nazi ideas of Aryan superiority and frustrated Hitler; one story, which may be apocryphal, holds that the German Führer refused to shake the hand of the black sport star (Watkins Reference Watkins2016). Whatever the case, many agree that the 1936 Olympics were high-charged political theater. In photographs depicting the medal presentation, for instance, Owens can be seen on top of the winner’s podium, with Germany’s Lutz Long behind him, both with their hands raised in their respective salutes to their country and its flag.

Why was Owen’s salute not recognized for its political symbology, while other silent gestures like the raised fists of John Carlos and Tommie Smith, or Kaepernick’s kneeling, are lamented as inexcusably political? The difference is not due to gradients of fame, athletic accomplishment, or even race, but rather to the impact of the hypervisibility black sport stars project to the world through protest. Owen’s salute may have been acceptable because it reinforced the relationship between sports and a liberal democratic ideology, which are supported by routine military participation in big sporting events and singing the national anthem, a tradition that spread across the sport industry amid a wave of post–World War II patriotism. In contrast, protest politics is rejected because its goals and tactics are outside and at odds with formal political systems (see, e.g., Tate Reference Tate1994 17), and because attention to racial or social grievances undermines the vision of national unity that sports propagate.

The empirical findings in this study provide new insight into this dynamic and answer Hartmann’s (Reference Hartmann1996) question about whether black sport activism has a measurable effect. They underscore the importance of recognizing black sport activists as nontraditional elite actors, as celebrities who not only exert uncomfortable pressures on their sport industry but who also have the potential to influence nontraditional political action. Our data show that black sport activism has a measurable effect on the behaviors that have to date been overlooked: nontraditional political behaviors that are no less essential to a functional democracy.

Considerably more work will need to be done to fully determine the influence of athlete activists and other celebrities. For example, although injustice continues to beckon celebrities to use their platform to advocate for a cause, conservative Republicans have also drawn on the capital of black celebrity to help reshape the party’s anti-black image.Footnote 14 Kanye West’s donning of Trump’s “Make America Great Again” trucker hat, for example, opens up new opportunities to examine the power of black celebrity in politics generally and to further explore the juxtaposition that progressive black sports stars, such as Kaepernick, pose to an ever-present mainstream American politics determined to move beyond issues of race.

Supplementary Materials

Tables A1–A4

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719002597