A March 2015 United Nations report on the war in Syria found that six percent of the population of 22 million had been killed or injured, some 80 percent lived in poverty, and the majority of children no longer attended school. Footnote 1 Satellite images show a country literally “plunged into darkness” with 83 percent of lights gone out, Footnote 2 and some 200 cultural heritage sites damaged or destroyed. Footnote 3 While the Islamic State (ISIS)’s crimes gain notoriety, the regime of Bashar al-Assad remains responsible for the lion’s share of civilian deaths. Escaping atrocities from imposed starvation to indiscriminate barrel bombs, more than 7.6 million have become internally displaced and 4.1 million externally displaced, as of this writing. Footnote 4 While Europe struggles to resettle a fraction of refugees, the resource-strapped counties on Syria’s borders buckle under a deluge whose political implications remain undetermined.

Observing these horrors, dignitaries denounce “senseless” tragedy. Footnote 5 Seeking to make sense of it, political scientists often turn to general concepts such as authoritarian survival and subtypes of civil war. Theories derived from these and other categories elucidate complex conflict dynamics. Yet they leave us to wonder how Syrians themselves understand the tumult remaking their country. That echoes an earlier tradition of structurally oriented scholarship on Syrian authoritarianism, the bulk of which treated citizens’ experiences of politics as epiphenomenal to regime institutions and policies rather than objects of study in their own right. Such gaps were conditioned by limited access to Syrians’ frank reflections on politics. An unprecedented outpouring of self-expression since 2011, however, invites a different kind of analysis.

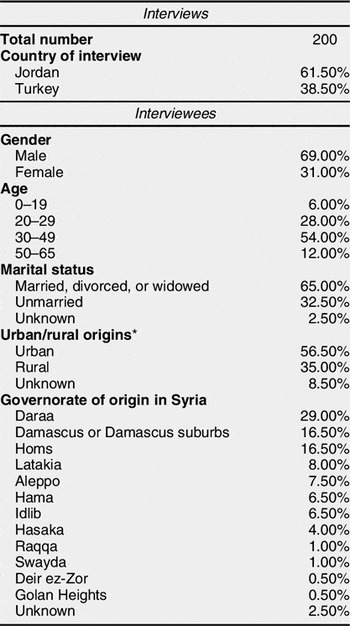

Probing one form of self-expressive evidence, I conducted open-ended interviews with 200 Syrians during 3.5 months of ethnographic fieldwork in Jordan (2012, 2013) and Turkey (2013). I find that individuals’ narratives coalesce into a collective narrative whose arc emphasizes change in the sources, functions, and consequences of political fear. Descriptive analysis of these narratives offers a window into the citizen-level processes by which regimes endure despite popular discontent, rebellions gain momentum notwithstanding repression, populations habituate to horror, and nations confront profound insecurity. More specifically, it offers three kinds of insight for understanding Syria and other cases of destabilized authoritarianism. First, analysis of personal narratives allows us to learn not only about the present, but also about a past obscured by citizens’ prior reluctance to speak about politics. Footnote 6 Ordinary people’s newfound willingness to tell their stories is akin to the opening of an archive into social attitudes and experiences under repressive rule; we should use it to reconsider what we thought we knew as well as what we still hope to uncover. Second, study of testimonials offers a special angle on questions of identity. To the degree that individuals make sense of themselves and their world by situating themselves in stories, Syrians’ narratives reveal how political fear shapes their understanding of what it means to be Syrian. Finally, analysis of the act of narration, no less than narratives’ content, displays processes of political agency and change. When authorities use fear to silence subjects, their talking about fear—articulating its existence, identifying its sources, describing its workings—is a form of defiance. Examining stories thus allows us to witness both an exercise in meaning making within a revolution and a revolutionary practice, in and of itself.

Experiences of fear in Syria might be as varied as are parties to the conflict. Due to dangerous conditions inside the country, I limit my focus to those who have become refugees outside it. Using a snowball sampling, I followed multiple entry points into different social networks to reach interviewees who varied by age, class, and home region. Nevertheless, like the refugee population at large, Footnote 7 the overwhelming majority of people I met were Sunni Muslims who supported the rebellion against Bashar al-Assad.

Personal narratives might contain omissions or misrepresentations, or might harden into social scripts. These complexities also exist with written documents, however, and can similarly be mitigated by critically comparing multiple sources. Footnote 8 Actors’ self-understandings provide vital insight into motivation and decision-making, which ultimately form the micro-foundational basis for social explanation. Footnote 9 It is especially important for the task of representing refugees due to dominant practices that render them “speechless.” Liisa Malkii argues that the desire to showcase refugees’ universal humanity often privileges pictures of their bodies at the expense of their words. As an alternative, she calls for a “historicizing humanism” that acknowledges displaced persons’ “narrative authority, historical agency, and political memory.” Footnote 10

Putting those elements at the forefront, I build on the work of Kristen Monroe, Elisabeth Wood, and others who demonstrate the value of oral history interviews for political science. Footnote 11 I begin by discussing how scholarship on contemporary Syria has been limited by ordinary people’s reluctance to speak about politics. I then explore four experiences of political fear that emerge in stories from Syrian opponents of Assad rule. I conclude with the argument that political fear offers a new lens on the evolving contours of what it means to be Syrian. Beyond Syria, I call for continued descriptive analysis of personal narratives as a tool for uncovering the social processes that stabilize or destabilize authoritarianism, for rethinking national identity, and for recognizing the changes that revolutions produce, whether or not they overthrow regimes.

Syrian Politics and Syrian Voices

Most foundational research on Syrian politics has adopted a structural orientation in general and a political economic focus, in particular. Several classic works trace the mid-century rise of rural and minority communities in the army and Baath party, social conflict before and after the Baath’s 1963 coup, and institutionalization of a “presidential monarchy” since Hafez al-Assad’s seizure of power in 1970. Footnote 12 These scholars scrutinize the Assad regime’s use of cross-sectarian alliances and a populist social contract to build allies, as well as its maneuvering of the party, state apparatus, and domination of the economy to establish social and political control. They trace how these elements, cemented by a pervasive security apparatus, defeated major domestic challenges in the 1980s. Together, these works paint an analytical portrait of an authoritarianism that appeared impressively stable, despite failure to produce economic growth commensurate with its burgeoning population. Footnote 13

Analyses of Assad’s succession by his son Bashar in 2000 largely sustained this structural and political economic orientation, probing what did or did not change under the popular young president. Footnote 14 Scholars describe how, despite initial suggestions of political reform, Bashar centered his agenda on neoliberal modernization and privatization. Some traced how this opening to global capitalism garnered middle-class enthusiasm for new consumer comforts. Footnote 15 Others argued that it redoubled collusive regime/business networks that bared conspicuous corruption and rendered the regime increasingly narrow and elitist. Footnote 16 Political economy research also documented inflation, unemployment, crumbling infrastructure, and welfare cuts, noting how they deteriorated living conditions for much of the population, Footnote 17 and especially the regime’s traditional peasant and worker clientele. Footnote 18

This indispensible scholarship made vital contributions to “demystifying” Syria Footnote 19 by painting a rich portrait of the social, economic, and institutional forces that buttressed authoritarian rule. Yet it did not typically address the experience of citizens living under it, apart from that which could be inferred from macro-relationships of power. This might have been due to the questions and explanatory perspectives that these works prioritized, but was also a product of the difficulty of accessing citizens’ perspectives in a country in which no opinion polls existed, state and self-censorship was the norm, Footnote 20 and few citizens discussed politics outside private homes. Footnote 21 Consequently, just as structurally-oriented researchers labored to make sense of unreliable statistics, Footnote 22 so did those exploring Syrian society inventively cope with data limitations. In this context, Lisa Wedeen broke new ground by scrutinizing the cult of Hafez al-Assad, as well as transgressions of it, such as political jokes and cartoons. In this way, she traced how citizens came to comply with permissible lines of speech and behavior although they did not believe in them. Footnote 23 Subsequently examining a new consumer culture under Bashar, Wedeen concluded that many aspiring Syrians were not simply acting “as if” they supported the system, but had become genuinely invested its ideology of the “urbane good life.” Footnote 24

This and other works circumvented constraints on free speech in Syria to create an invaluable window into the society component of state-society relations. Anthropologists and cultural scholars did likewise. Delving into Syrian film, literature, and television, they investigated both their subversive political content and their role in reflecting and shaping popular attitudes. Footnote 25 They also studied artists’ relationships with the regime as a larger window into citizens’ navigation of the incentives and restrictions that it imposed. Footnote 26 In this way, analysis of creative production offered something of a proxy for the difficult-to-reach voices of ordinary people freely discussing their thoughts about life under Assad rule. Yet it remained a proxy.

The uprising that began in 2011 transformed this situation. In what one report called a “renaissance of freedom of expression,” Footnote 27 Syrians of different backgrounds have come to speak about politics with unprecedented openness. Scores now regularly take to social media and especially Facebook, unbanned in February 2011, to share their views. Dozens of new publications, websites, and television and radio stations offer forums for commentary, discussion, and story telling. Footnote 28 An explosion of art, including painting, graffiti, banners, caricature, song, theater, dance, satire, and creative writing, engages political themes. Footnote 29 Hundreds of thousands of works of filmmaking, ranging from documentation on cell phones to semi-professional productions, do likewise. Footnote 30 First-person essays and diaries offer intimate glimpses of individual lives. Footnote 31 Beyond these works, journalistic coverage reveals the extent to which Syrians, even in the regime-controlled capital, are willing to be interviewed with candidness unimaginable just five years ago. Footnote 32

Though many of these expressive forms extend cherished traditions, a revolution has occurred in the sheer volume of production, its scale and speed of circulation, and its expressly political content. Footnote 33 A few political scientists have made use of such sources as data for analysis or new questions for research. Reinoud Leenders scrutinizes Syrians’ YouTube footage for slogans, imagery, tactics, social relationships, and motivations that help explain the uprising’s onset. Footnote 34 Wedeen draws on fieldwork in Syria, conversations with displaced Syrians, and analysis of film and television to account for the ambivalence of Syria’s two largest cities toward the protest movement. Footnote 35 While these works give primary place to Syrians’ self-expression and observed lives, much of the research on the current conflict instead centers on generalized concepts or processes. Applying social movement theory, several works examine the revolt’s emergence and spread in terms of opportunity, threat, networks, framing, information technology, and the escalatory effects of repression. Footnote 36 Assuming the perspective of authoritarian durability, others highlight the regime’s failure to “upgrade” without alienating important social constituencies. Footnote 37 Alternatively, others credit the regime’s success in adapting its survival strategies once a national revolt came underway. Footnote 38 Attentive to within-country variation, some scholars scrutinize the role of subnational regionalism, Footnote 39 divergent economic interests, Footnote 40 or sectarian/cross-sectarian ties Footnote 41 in shaping the conflict’s uneven unfolding. Situating Syria in larger security debates, others ask what literature on civil war can teach us about this case Footnote 42 or how Islamic fundamentalism and geopolitics affect its dynamics. Footnote 43

All of these factors shape dynamics in Syria. However, they do not bring us closer to ordinary Syrians’ experiences than did research under the pre-2011 constraints. Moreover, the factors that they emphasize are sometimes quite distant from those of greatest salience to people living the conflict. This is what I found in carrying out interviews with 200 Syrians in Jordan and Turkey (refer to table 1).

Table 1 Interviewees: Basic demographics

* Urban status is accorded to governorates’ capital cities, as well as Qamishlo and all Damascus suburbs, given their dense populations and/or proximity to densely populated areas. Other locales are regarded as rural.

My interviews, nearly all in Arabic and most audio-recorded, ranged from twenty-minute one-on-one conversations to group discussions involving several individuals over hours, to life histories recorded over days. I asked interlocutors to recount their experiences in Syria’s current upheavals, including their thoughts on politics before 2011 and their subsequent experiences with protest, war, and displacement. My aim was to uncover how individuals make sense of their country’s political reality and themselves as actors within it. I find that a theme of striking prominence across these interviews, echoing abundant print, audio, and visual sources, is political fear. What might political scientists learn if we, moving inductively from Syrians’ self-understandings rather than deductively from theoretical frameworks, give this factor primary place in our analysis?

Four Types of Fear in Syria

Corey Robin defines political fear as “a people’s felt apprehension of some harm to their collective well-being … or the intimidation wielded over men and women by governments or groups.” Footnote 44 In political science today, the most sizable research program on fear appears to be political theory examinations of contemporary Western society, focusing on the linkage between fear and liberalism Footnote 45 or consumer capitalism, Footnote 46 or anxieties about terrorism or foreigners, especially since 9/11. Footnote 47 Exploring the contemporary Middle East, I find very different political fears. My research does not allow me to isolate fear from other factors that influence how individuals act politically or tackle the thorny question of how such individual-level emotional states aggregate to impact collective outcomes. However, it can offer a new way of mapping conflicts such as that in Syria. Conventional analyses dissect the Syria war in terms of its major political players or periodize it according to military or diplomatic turning points. By contrast, I plot the rebellion as four types of fear patterning the lived experience of those who have championed it. Analytical distinction between these types can elucidate the range of political circumstances and processes contained in the single affect that people feel—and articulate—as fear. They offer an emotional lens on the trajectory from durable authoritarianism to mass protest, militarization of conflict, and protraction of instability, though these and other fears might occur or recur in other sequences, as well. The following discussion uses Syrians’ narratives to illustrate.

Silencing Fear

Autocratic leaders’ threats to punish citizens for political transgressions can generate a silencing fear that encourages submission to their coercive authority. Observers of Latin American dictatorships described how surveillance, intimidation, and detentions produced general climates of insecurity and compliance. Footnote 48 Likewise under Hafez al-Assad, Volker Perthes noted that security forces “deeply penetrated society” and “succeeded in conditioning the behavior of most Syrians.” Footnote 49 An exception that proved the rule was the period from 1976–82, when various associations agitated for human rights and the Muslim Brotherhood violently attacked regime targets. Authorities responded by killing, imprisoning, or disappearing tens of thousands of citizens, as well as flattening entire sections of the town of Hama. Footnote 50

The terror that the 1980s “events” inflicted upon the population cannot be overstated. Hushed awareness of that repression, as well as political imprisonment and torture thereafter, admonished people of the danger of challenging the regime. One man from Daraa described this implanting of fear in terms that echoed Syrian novelist Zakaria Tamer’s allegory about citizens as a once-proud tiger broken by a shrewd master:

Hafez al-Assad tamed the Syrian people by using security and military rule. It was like you have a wild animal that you want to make a pet. This turned Syria into a big farm … He killed political life. Footnote 51

A twenty-something from Homs explained how citizens were tamed from their earliest years:

He programmed us. You’re six years old in school and look at the notebook, and you’re looking at a picture of Hafez al-Assad. You enter the classroom and see Hafez al-Assad’s photograph. You go outside and chant, “With our blood and with our souls we’ll protect you, O Hafez.” They start from the time you’re born. Footnote 52

Bashar’s assumption of power generated hopes for change. In an opening known as the “Damascus Spring,” activists spearheaded forums for debate and petitions urging reform. Footnote 53 Some found that a major challenge was their compatriots’ trepidation of engaging in politics. As Radwan Ziadeh reflected on that period, “My goal throughout was to help whittle away at the wall of fear that kept the Syrian people from rising up in demand of their rights.” Footnote 54 That fear was not unfounded: within months, the government brought the political opening to an end with arrests, closures, and malicious rhetoric.

Though many aspects of public life took on a different façade under Bashar, the regime’s refusal to accommodate opposition or human rights did not. Photographs of the president and ubiquitous party or security installations reminded citizens of the regime’s watchful eyes. “You get scared just walking by the Baath headquarters,” a university student said of Aleppo. “Outside there are guards with weapons. The windows are closed and you have no idea what’s going on inside. It’s like a ghost house.” Footnote 55 Armed agents brought this intimidation to the street-level. “A single security officer could control a town of 20,000 people holding only a notebook, because if he records your name, it’s all over for you,” a lawyer remarked. Footnote 56

Whether or not the regime actually wielded this capacity for repression, the fact that many believed it did rendered it a felt reality with important effects. No less powerful, citizens’ worry about covert regime collaborators created a hazy air of suspicion. “Nobody trusted anyone else,” a rural dentist explained. “If anyone said anything out of the ordinary, others would suspect he was an informant trying to test people’s reactions.” Footnote 57 A young man joked, “My father and brothers and sisters and I might be sitting and talking … And then each of us would glance at the other, [as if to think] ‘Don’t turn out to be security!’ By God, it’s just like George Orwell’s 1984.”Footnote 58 Syrians I met expressed little doubt that the surest way to invite the state’s wrath was to discuss politics. A man from rural Daraa explained:

We don’t have a government. We have a mafia. And if you speak out against this, it’s off with you to bayt khaltu—“your aunt’s house.” That’s an expression that means to take someone to prison. It means, forget about this person. He’ll be tortured, disappeared. You’ll never hear from him again. Footnote 59

If speaking about politics invited punishment, silence was the rational strategy for survival. Again and again, Syrians told me that they were raised on the warnings “Whisper! The walls have ears” and “Keep your voice low.” A man from Deir ez-Zor added, “In Syria, there was no such thing as ‘What is your opinion?’” Footnote 60 Another from the Damascus suburbs was more adamant. “We didn’t even mention the name ‘Bashar Al-Assad,’” he said. “Fear was that constant.” Footnote 61 Another agreed: “Even if you wanted to say something you’d stop yourself, because you’d see everyone around you was intimidated and silent. If you spoke, you’d stick out, and nobody would want anything to do with you.” Footnote 62 Apprehension was particularly acute for writers struggling to avert the shifting redlines defining tolerated speech. “No feeling overpowers Syrian journalists more powerfully than fear,” a writer asserted in an exposé titled Book on Fear. Footnote 63

For citizens living in and molded by this political environment, fear was not simply a regime strategy. It could also be deeply formative of their sense of self and being in the world. A disposition to silence might even become a second nature carried beyond the homeland, as explained by one man who left Syria as a child:

When you meet somebody coming out of Syria for the first time, you start to hear the same sentences. That everything is okay inside Syria, Syria is a great country, the economy is doing great … It’ll take him like six months, up to one year, to become a normal human being. To say what he thinks, what he feels … Then they might start … whispering. They won’t speak loudly. That is too scary. After all that time, even outside Syria you feel that someone is listening. Footnote 64

Fear narrowed a sense that change was possible, and hence the perceived need to fight for it. “The regime ‘cuts our wings’ and dictates the limits of our dreams,” a writer penned. “By fear, oppression, ignorance, corruption, the ‘system’ has become the only possibility … the graveyard of ambition, of ideas, of innovation, of hope.” Footnote 65 A young man from Hama added, “A Syrian citizen is a number. Dreaming is not permitted.” Footnote 66 Still, this silencing fear was not absolute, as various forms of subversion revealed. Wedeen thus notes that Assad’s “nontotalizing” authoritarianism was less frightening than Sadam Husayn’s Iraq. Footnote 67 Yet she also explains why it was difficult to assess how afraid Syrians really were: to admit that one submitted out of fear would contravene the cult of Assad, in whose language Syrians knew to demonstrate fluency.

It is thus only now, after the grip of silencing fear has loosened, that researchers are able to investigate fully how Syrians experienced it in the past. One element that such research can explore is the ways in which the fear chiseled by the collective memory of traumatic events may have faded over time. A thirty-something from Hama alluded to this process:

[Our parents’] generation lived through Hama. My aunt was pregnant at the time. My parents took her to the hospital. They had to stop at checkpoints on the way and saw corpses lined along the road.

My father carries that sight inside him until now. Whenever we’d watch anything on TV related to politics, he’d say, “Turn off the television!” He couldn’t even bear to watch a political TV show. That’s how afraid he was.

My generation is also afraid—but not like them. I now say to my father, “Why were you silent all of those years?” We say this to their entire generation. Footnote 68

A man of about the same age, also from Hama concurred. “We are ‘the copy of the copy,’” he said. “We didn’t get the original fear. We just took a copy of it from our families.” Footnote 69 Continued research on these and other processes can investigate the manifold ways in which the regime instilled silencing fear and people responded. It can gauge how fear varied by class, residence, and other factors, theorize its enduring legacy for individual subjectivities and political culture, or probe possibilities for its reemergence in new forms or due to new impetuses.

Surmounted Fear

The inverse of silencing fear is surmounted fear. In terms of the truism that fear provokes fight or flight, silencing fear motivates flight into disengagement, whereas surmounted fear empowers the fight for political voice. Fear is surmounted, rather than silencing, when one is aware of potential punishment for political transgressions, but musters the courage to act anyway. Footnote 70

The notion of surmounted fear undergirds Syrians’ description of the uprising as “breaking the barrier of fear.” Variations on that saying are so ubiquitous that the “start of demonstrations” and “collapse of fear” sometimes appear to be nearly synonymous references. Footnote 71 That collapse was not inevitable. Footnote 72 Syrians I met said that they were elated by the uprisings that forced authoritarian presidents to resign in Tunisia and Egypt in early 2011. Still, many believed that Syria would remain a “kingdom of silence” immune to the region’s revolutionary tide. Footnote 73 Gradually, however, the mood shifted. Observers noted Syrians’ daring to broach political topics. Footnote 74 A spontaneous protest in the Damascus market emboldened bystanders, as did vigils in solidarity with revolts elsewhere in the region. Footnote 75 Syrian exiles online called for a “Day of Rage” to launch revolution on March 15. A few localities witnessed demonstrations, but armed personnel quickly suppressed them.

Meanwhile, in the southern province of Daraa, security forces arbitrarily arrested some 15 children after anti-regime graffiti appeared on the wall of their school. Footnote 76 Relatives beseeched the provincial police chief for their release and he dismissed them with a vulgar insult. Against this backdrop, a mass demonstration took shape during which security personnel killed two protestors. As protests continued and grew that week, a shift set in that one participant described as an awakening:

Something took shape in the minds of young people. It was as if they were sleeping and a new culture woke them … [People asked themselves]: ‘Why can’t there be change here? … Why should we allow a small group of people to rule us? We can pay the price.’ Footnote 77

Casualties continued, news spread, and communities across the country held demonstrations of their own. The regime’s response, offering some conciliatory measures while applying violent repression and denouncing protestors, brought more oppositionists to the streets. Within weeks, a popular uprising called for the regime’s overthrow.

Raymond Hinnebusch and Tina Zintl present a persuasive account of the structural circumstances that drove many Syrians to want change, but acknowledge that structure only takes us so far in explaining the popular upsurge. “Agency,” they add, “is crucial to understanding what tipped the balance.” Footnote 78 In discussing what personally tipped them to protest, people whom I met highlight the degree to which they experienced agency and the surmounting of fear as one and the same. In lieu of a full analysis of the diverse and contingent mechanisms that propelled that shift, I present the narratives of three individuals describing their participation in demonstrations. The first, B.D., is a mother in her mid-thirties, ethnically Kurdish and from Aleppo:

Oppression was residing in us. It was part of our life … like air, sun, water. We didn’t even feel it. … And then you—in one second, in one shout, one voice—you blow it up. You defy it and stand in front of death … You have an inheritance and after thirty years, you slam it on the ground and shatter it.

I encouraged my sister’s children to come with me [to demonstrations]. I felt that, if they didn’t try that experience, they’d be missing the real meaning of life … At first their voices were timid. But every time they repeated the chant “the people want the downfall of the regime,” their voices got louder. The sound rose until you heard it echo between the buildings. All the people living in the buildings came out to see what was going on.

Don’t even imagine that it was easy to go out to a demonstration. No amount of courage allows you to just stand there and watch someone who has a gun and is about to kill you. We—as a people—were certain that they were going to kill us. Fear didn’t go away because we knew that there was death. But still, this incredible oppression made a young man or a young woman say “God is Great” … And when those words are said, you and 200 other people are ready to call out … Your voice gets louder … You shudder and your body rises and everything you imagined just comes out. Tears come down. Tears of joy, because I broke the barrier. I am not afraid, I am a free being. Your voice gets hoarse. Sadness and happiness and fear and courage … they’re all mixed together in that voice, and it comes out strong. Footnote 79

In the second testimonial, C.J., a twenty-something man from Daraa, describes watching his town’s first demonstration as it marched in his direction:

When I first saw the demonstration, it was a weird feeling … Nothing like that had ever happened before. Until then, we’d only had pro-regime demonstrations. …

The demonstration started. As we were chanting, my brother was taking photographs with his cell phone. The police caught him and put him in their car. Then the entire crowd attacked the car. They dragged him out and the police ran away ….

[Then] the first two martyrs were killed. The second day there was a funeral procession. We didn’t expect anyone to participate, because of the killing … But we went to the funeral and more than 150,000 people attended. People came from all the surrounding villages.

Every group had its own reasons. But in general, people are under pressure … Everyone agreed that the regime is criminal, [but] we were afraid to go out. Then the chance came to us … If we lost it, does that mean we’d never be able to go out again? Also, we knew that if we went back, the regime would come and arrest all the young people who went out the first day. They’d all die in prison … So there was no choice. We entered a road with no return. Footnote 80

The final narrative is from N.H., a business school graduate from the Damascus suburbs, in his mid-twenties. He describes his anticipation before his first protest:

I was waiting for March 15th like I was waiting for a date. … The number of people signed up for the Facebook page [The Syrian Revolution Against Bashar al-Assad] reached 12,000. I imagined 1,000 would show up.

I started meeting with a guy who became one of the first activists in my town. Let me call him Nizar … He told me I needed to have a specific role [and] bought me a camera. We bought a shirt and made a hole in the pocket. We put the camera in and I wore a jacket over it. He told me that, as soon as I got to the protest, I should turn the camera on. When I saw an opportunity to record, I could open my jacket.

I’ll never forget March 15th as long as I live … The first person to start shouting was a man. Word spread that he was from the regime and was encouraging people so that they could then arrest us. Then this girl spoke out. Her dad had been arrested in 1982. She shouted, “God, Syria, freedom, and nothing more!”

No one joined her. To be honest, I was scared. Everyone was watching. But Syrians always feel affected by the bravery of a woman. A woman is not braver than me, so I joined in. My voice got louder and louder. The chanting made me forget all about the camera.

Then the security cars came … I withdrew. I felt a sort of fear. I moved back and watched. The security forces arrived and started to beat people … I began to feel sad. I hated the world. I hated the situation. I hated life. I felt sadness. Sadness for why things are the way they are: why don’t we have plans, why don’t we have organization, why, why, why … Damn, how those guys were chanting for the benefit of the entire nation and beaten up. What if it was me who had been beaten up instead … and everyone was just looking at me, doing nothing? I wanted to drink water, to walk away, to leave.

[I came home] and thought for hours: “This is a revolution, this is what happens in a revolution. I could get beat up and I could die. This is for a goal. Either I accomplish the goal or I die.” I put pressure on myself. “This is a corrupt regime. You shouldn't expect anything else from it.” … I visited Nizar. He encouraged me: “You need to toughen up and be aware.”

Going out [to the next demonstration], I bid my mother and father farewell … I didn’t think I was going to return home again … [But] if I don’t sacrifice and other people don’t sacrifice, the revolution is dead. If someone else is going to sacrifice, he needs to feel my presence. There needs to be unity. Footnote 81

These rebellion supporters bring common themes to the fore. All admit that, aware of the danger of dissent, they never ceased to be afraid. Nonetheless, various factors helped them act through or despite that fear. The first speaker describes the emotional relief of vocalizing dissent long held privately. The second indicates a rational calculation that the risks of protest were indistinguishable from those of staying on the sidelines, while its benefits would never be higher. The third highlights interpersonal factors that emboldened risk-taking, including an encouraging mentor and norms of masculinity. All testimonials converge in suggesting that protest was no simple task of revealing concealed preferences. Footnote 82 Rather, it was a transformative actualization of a political agency that had been suppressed. The process of surmounting fear entailed both a sober readying oneself for the possibility of death and an auto-emancipation that was visceral in its power. In this context, disappointing oneself by withdrawing from a protest could cause profound despondency, while succeeding to chant felt, as another woman told me, like hearing one’s own voice for the first time. Footnote 83

The testimonials also indicate how this intimately personal awakening was socially embedded. One’s shouts gained power by mingling with others; in the first speaker’s telling, the collective cry was so mighty that it rebounded on the walls and beckoned others to join. Demonstrations embodied a Durkheimian “collective effervescence” that generated a euphoric energy. Overwhelming passion brought the third speaker to forget his camera and spurred a crowd to attack a police car to free the second speaker’s brother. Adding to these psychological and social processes were ethical impetuses. Regime repression against unarmed protestors triggered a sense of indignation and obligation that compelled people to act. The second speaker notes that thousands attended the funeral to honor the revolt’s first martyrs, even though they anticipated repression. The final speaker judged that, if others paid a high price, he had a duty to do likewise. Indeed, he would later spend months in prison for his activism.

These narratives suggest that revolt became possible when people came to see silencing fear not as immutable, but as an impediment that they could overcome. Further work, building on relevant research in social movement theory, Footnote 84 can continue to explore the emotional, social, moral, and cognitive processes that produce this change. The more we learn about these processes, the better will be our overall understanding of what fear is and how it functions. Footnote 85 Such understanding can help us rethink conventional theories of rebellion that treat fear as an indicator of the costs and risks of collective action. Guided by protestors’ self-understandings, we can explore how fear, and overcoming fear, is not merely a response to external conditions, but also constitutive of actors’ internal sense of self.

Semi-Normalized Fear

Silencing fear and surmounted fear are two sides of the same coin of subjugation and rebellion. In both cases, fear clearly directs decision-making insofar as it is grounded in a tight linkage between expected harms and awareness of the behaviors that avert or hasten them. When danger becomes relentless or extremely unpredictable, however, such clarity disappears. The result might be a new semi-normalized fear. On the one hand, arbitrary danger offers no escape. On the other, that very inescapability renders fear the backdrop of daily life. As long as people must fulfill basic needs, they have no alternative but to become accustomed to terror.

Scholars have dubbed this duality the “trivialization of horror,” Footnote 86 “banalization of fear,” Footnote 87 “normalization of the abnormal,” Footnote 88 “permanent cohabitation with death,” Footnote 89 or “fear as a way of life.” Footnote 90 If silencing fear is an externally imposed weight and surmounted fear an internally mobilized courage, semi-normalized fear is one’s behaviorally practiced navigation of conditions of persistent threat. As with other fear types, semi-normalized fear presents people with a choice between submission and defiance. What individuals must accept or resist is not the actors who generate fear, however, as much as the feeling of fear itself.

Semi-normalized fear came to large swaths of Syria as demonstrations spread and regime forces killed, imprisoned, or tortured tens of thousands. Though mass nonviolent demonstrations dominated the revolt through summer 2011, citizens took up guns increasingly over time. Army defectors began offensive operations under the banner of the Free Syrian Army (FSA), and eventually hundreds of disparate brigades pushed Assad’s forces from rebellion strongholds. The regime responded by intensifying to artillery, airpower, and missiles. Footnote 91 It committed massacres in some places and scorched earth “rampant destruction” in others. Footnote 92 Independent human rights investigations judged regime actions, especially large-scale military assaults on restive communities, to constitute crimes against humanity. Footnote 93 In January 2012, the al-Qaeda-linked Nusra Front announced its formation. This and other Islamist groups, many enlisting foreign fighters, used superior funding and organization to expand their influence over what began a primarily civic, national uprising. Footnote 94 By summer 2013, armed rebels had gained control of some 60 percent of Syrian territory. ISIS emerged from the Nusra Front and imposed its brutal rule on towns that it seized.

For civilians living under these conditions, war ushered in a new experience of fear that was simultaneously petrifying and quotidian. My interlocutors described shelling and bombardment as ru‘ab—terror. They explained how families would crouch together during nighttime raids, listening to blasts and wondering where explosives would hit next. In my interviews, it was women who discussed these horrors in the most bodily, sensory terms. Many emphasized the element of sound, as did members of one family from rural Idlib:

Mother: The first time we heard the sounds of planes and shelling, we women were so afraid that we cried … You’d keep hearing it in your head even when it wasn’t there anymore.

Daughter-in-law: Until now, whenever I hear the sound of a plane I get so scared that I have to go to the bathroom!

Daughter: I was in the hospital giving birth to my son, and I needed to have an operation. I was on [the operating table] and heard the planes. I was more afraid of bombing than the pain of surgery. Footnote 95

Syrians insisted that more frightening than death was the prospect of arrest. Independent investigators accused the regime of torturing detainees “on an industrial scale” aimed less at extracting information than at terrifying communities when mutilated bodies returned home. Footnote 96 People I met saw death by bullets as more merciful than the starvation and torture that they regarded as synonymous with imprisonment. As one expressed it, “I pray to God: ‘Please let them kill me instead of taking me alive.’” Footnote 97 Another terror worse than death was retribution against loved ones. “The regime understood that people were ready to die,” an FSA officer explained. “So it tried to get at them by taking revenge on their families … Before executing any plan, we started calculating: If the regime is going to reach an area, who is considered symbols of the opposition? We would try to get their whole family out.” Footnote 98

This violence was terrorizing, yet also normalized in several ways. First, people claimed that mortal danger became routine. “Everyone is mashrua‘ shaheed—a ‘martyr project’ or ‘martyr-in-the-making,’” a man originally from the Golan Heights explained. “Whoever demonstrates is a martyr, and whoever holds him is a martyr, and whoever washes him is a martyr, and whoever cries for him is a martyr, and whoever buries him is a martyr.” Footnote 99 Killing became so ordinary that death from old age or illness seemed exceptional. A man from Idlib exclaimed, “It has been so long since I heard that someone died from natural causes!” Footnote 100

Second, awareness of violence produced new kinds of knowledge. Many conveyed this by referencing the ways that even children became familiar with the weapons of war. “My three-year-old can tell the difference between different missiles and rockets,” a mother from Aleppo said. Footnote 101

Third, repression became integrated into the timetable of life. A woman from Latakia explained that loyalist militias raided houses every Thursday and Friday. Neighborhood residents stayed with relatives elsewhere on those days to avoid encounters that could result in arrest, or worse. Footnote 102 A predictable schedule of violence also directed medical relief, as a physician from Homs described:

Most massacres occurred after Friday prayers. Some people were going to die and some were going to get hurt, but people still went out to demonstrations … We’d go to the hospital and wait. This was every Friday, every Friday, every Friday.

The demonstration would begin. A little while later, a pick-up truck would arrive at the hospital loaded with people. We’d fill all the hospital beds and then line people on the floor to examine them. We couldn’t let people stay at the hospital, because security agents were going to come [and] arrest the injured people and those treating them. So we provided … necessary first aid and immediately sent them back to their homes.

During the rest of the week, we’d prepare pseudonyms … We had to notify the security forces of the names of our patients, so we’d use the names of dead people. That’s how we worked. Footnote 103

Fourth, violence was assimilated into geography, leaving few places unmarked by death. “People couldn’t reach cemeteries, so they buried bodies wherever they could,” a man from Palmyra mentioned. “Parks and backyards became cemeteries. Someday the land will talk about all those who are buried in it.” Footnote 104 An FSA fighter described how zones of warfare and everyday affairs existed adjacently. People adapted as if to streets closed for construction:

Here is one street in town. We block it with stones from both sides. On the other street, people are shopping or going for a walk as if nothing is happening. You find people smoking water pipes, drinking coffee, talking, stuff like that. At the same time, shelling never stops. Over there, tanks and mortars are firing, but people just avoid that street. Footnote 105

Fifth, normalized terror was apparent in an immunity, professed or real, to the shock of violence. A young man from the Idlib countryside describes that accommodation:

In the beginning, people were so scared from the sound of explosions. Then it became totally normal. In the summer, it was hot, and there was no electricity. What could people do? They went out on the roofs, even though there was shelling and this exposed them. Footnote 106

The FSA fighter from Idlib expressed similar sentiments:

In the beginning, one or two people would get killed. Then twenty. Then fifty. Then it became normal. If we lost fifty people, [we thought], thank God, it’s only fifty!

Last year, they shelled the market area on Eid al-Fitr [the holiday marking the end of Ramadan]. People left the market. A half an hour later, everyone returned and went back to buying and selling.

I can’t sleep without sounds of bombs or bullets. It’s like something’s missing.

For rebellion supporters whom I met, the major cause of semi-normalized fear was regime violence. Nevertheless, that fear did not buttress the regime’s coercive authority as in decades past. Before the uprising, the threat of punishment—manipulated with greater, but not absolute, discrimination—encouraged most people to submit to power. For many, application of violence during the revolt had the opposite effect. Primarily, the excessive character of violence undermined the regime’s legitimacy. “In our eyes, the regime collapsed with the first bullet that it shot at demonstrators,” a fighter asserted. Footnote 107 At the same time, the arbitrariness of violence suggested that there was no prospect of amnesty. If you were going to be punished regardless, why not rebel?

An activist who held two passports but chose to remain based in Syria shrugged that people either accepted the potential of dying at anytime or, provided they had the means, fled the country. Most of my interlocutors had chosen escape and were recalling experiences before doing so. Their descriptions were likely colored by memory and the context of speaking to a foreign researcher. They may have exaggerated danger to justify, to themselves or me, having left. Nevertheless, descriptions of semi-normalized fear from interviewees with years in exile were nearly indistinguishable from those that I collected from new refugees or people who continued to live in Syria but happened to be traveling outside it. Analysis of their stories can contribute to research on civil wars that, Wood argues, has given relatively little attention to social processes such as the transformation of actors and norms. Footnote 108 Voices from Syria suggest that one important social process in cases of intrastate violence is habituation to fear. Future research can examine the impact of this experience of fear upon political ideas and practices, as well as its implications for the postwar period.

Nebulous Fear

Semi-normalized fear ends when direct threat of violence is escaped. Relocated to safety, however, war survivors continue to cope with injury, trauma, death of loved ones, destroyed property and livelihoods, impoverishment, or displacement. These and other torments mark the loss of some aspects of their once-stable world without offering new permanency to replace them. They can thus give rise to a nebulous fear of an indeterminate future. Such fear remains acute as long as conflict persists and individuals speculate about what will become of their communities, nation, state, and the reality that they once called home. Scrutiny of Syrians’ expressions of nebulous fear offers a fresh angle on uncertainty as a variable in political decision-making. It shows it to be not only a circumstance complicating rational calculations, but also a factor destabilizing actors themselves.

Among Syrians I met, one strand of nebulous fear centered on the fate of the uprising. Some who championed revolution feared that the toll of brutality was undermining its greatest achievements. A man from Raqqa observed:

What we fear now is this phase of moving into the unknown. I fear people losing their sense of helping each other. Some people are so desperate and hungry, they’re closing in on themselves, focusing on what they can get for their own families. That goes against the solidarity we had at the start. Footnote 109

Those who sacrificed for the goals of freedom and dignity also expressed fear that their rebellion was being hijacked by foreign agendas. An activist from Amouda was one of many who pointed to radical Islamist groups as the main source of that fear:

I went out, I was arrested, I worked, I demonstrated … And then ISIS or some other group comes, and little by little they … steer the revolution in the wrong direction … You did all these things for the revolution, and you see that things are only getting worse … Fear of the regime was broken. But then there started to be fear of the revolution itself. Footnote 110

Many Syrians blamed the rebellion’s going astray on what they called “political money.” Echoing what I heard repeatedly, an FSA officer asserted that external patrons’ funding of different rebel groups was the main cause of rebels’ fragmentation. He repeatedly used the word ya’as—“despair” as he described the state of the conflict in 2013:

Many countries have interests in Syria, and they are all woven together like threads in a carpet. Qatar and Turkey support the Muslim Brotherhood and want them to take over in Syria. Saudi Arabia does not want the Muslim Brotherhood. The Gulf countries are terrified of Iran. Israel is worried about the Golan. We don’t know where this leading. All we know is that we’re everyone else’s battlefield.

If there is not a decisive change soon, there is going to be total chaos in this country … Most of the calls I get are from Syrians desperate for aid of one kind or another. What can I tell them? Many times, I don’t even answer the phone. There are times I wish I could forget. When I just want to take my wife and kids and go somewhere and raise my family. Footnote 111

This speaker’s words revealed the blurred line between the geopolitical machinations of states and the anguish of ordinary people who live their consequences. He feared succumbing to hopelessness. For another former activist, that had already come to pass:

There is no longer a role for revolutionaries. Now there is only armed struggle or relief work … First there was fear [of the regime], then there was terror [of violence], and then the next stage is indifference. Life and death become the same … and you just don’t care anymore. Footnote 112

Another activist added that prolonged uncertainty was undoing the very sense of personhood that her surmounting of fear had helped actualize:

One day I was visiting a doctor. She asked me to relax because I was very tense. I realized at that moment that I’d forgotten how people relax.

I believe [everyone] forced to leave Syria is like us. We can’t find ourselves. Myself, as a person, I forget her features … It’s like I’m watching what is happening from behind glass. I can’t feel my surroundings, because my feelings are still in Syria. Most Syrians are suffering the same feeling … We’re tired, and we can’t bear any more blood. We’re afraid. We’re afraid for Syria. We’re scared about the long term. Where will we end up? Where is the country heading? Footnote 113

A young fighter in hospital after a leg amputation similarly expressed how identity and politics melded in feelings of uncertainty and grief:

You lose the fact that you used to be a person. If we could be sure that we’d succeed in the end, then I’d have no regrets. Without that, I don’t know.

I think back to the beginning … what we lived those days can never be repeated. It’s impossible to feel that again. We felt like we were doing the greatest thing in the entire world.

We know that freedom has a price. Democracy has a price. But maybe we paid a price that is higher than freedom and higher than democracy. There is always a price for freedom. But not this much. Footnote 114

The longer violence has lasted, the higher that price has climbed. A chemical weapons attack killed hundreds of civilians one night in August 2013. Improvised barrel bombs dropped from helicopters continue to kill many more. In January 2014, 55,000 photographs were released evidencing systematic torture and starvation in regime prisons. Footnote 115 One exiled Syrian articulated how that newsbreak, recorded in history as another landmark of war, was experienced by many Syrians as the most personal of fears:

The most difficult part of the torture pictures … is not … the decomposed flesh, the starved bodies …or even the knowledge that the torture is both widespread and systematic. These things have always been elements of our Syrian reality … What is so difficult that I do not think we have the strength to overcome, is the fear that some of these pictures may show us the body of someone we know and we hope is still alive. Footnote 116

Looking Ahead

A conversation on Facebook in fall 2013 captured, with pride, sadness, and bitter humor, the tremendous changes in political fear that Syrian oppositionists have experienced in just five years:

Post: The most important and beautiful thing about the revolution was that people rid themselves of fear and the words, “Whisper, the walls have ears” … The most difficult thing today is that the … old fear has returned, except that it is fear not from the regime, but a different party.

Comment: Yeah, that’s true. But there are no more walls left, anyway. Everything’s gone. Footnote 117

These words reveal a trajectory from a silencing fear planted from above, to a surmounted fear powered from within, to adaptation to unremitting danger, and then to anxiety about an uncertain future. These four experiences of fear mirror the chronological flow of recent history in Syria, yet also indicate the potential for reversals. In the exchange above, the first commenter’s dismay about the new “party” generating old fears refers to ISIS. Such was echoed in an Amnesty International report on life in ISIS-governed territories, tellingly titled Rule of Fear. Footnote 118 It was also made clear to me in January 2014, when I mentioned “the barrier of fear” to an activist from northern Syria who unhesitatingly responded: “You mean fear of ISIS, right?”

That reaction illustrated how much had changed, yet not changed, in areas slipped from regime control. Some civilians living under ISIS would muster the courage to protest what they viewed as a new form of tyranny, sometimes using methods that they had used against Assad. Footnote 119 They thus once again transformed silencing fear into surmounted fear. At the same time, violence by and against ISIS normalized yet another wave of terror. In June 2014, ISIS seized parts of western Iraq and declared it, in addition to thousands of miles of Syrian territory under its grip, an Islamic caliphate. That September, a U.S.-led coalition began airstrikes on ISIS targets. “We don’t know who’s bombing us anymore,” one civilian told a reporter. “There are way too many airplanes in the sky; it seems as if they need a traffic police officer to coordinate their flights.” Footnote 120

Voices such as these typically make it into mainstream political science only as anecdotal illustrations on the sidelines of hypothesis testing. I have sought to show why descriptive analysis of such sources deserves more serious consideration. Such data carry limitations as do all data, as well as complications particular to their inter-subjective nature. Navigated with careful and critical triangulation, however, analysis of personal testimonials can enrich our understanding of motivation, decision-making, and what is at stake in processes of popular mobilization and political transition.

Such analysis makes a contribution to three realms of inquiry, in particular. First, when regimes that suppress free speech are unsettled, citizens’ stories offer information with which one may both examine the transitional processes underway and reexamine scholarly interpretations of the past. No observer of Syrian politics since the 1970s would deny the significance of political fear in the Assad order. However, most relegated it to the background of studies centered on other factors. For example, Perthes and Wedeen converge in arguing that Syrians’ submission to Hafez al-Assad ought not be read as endorsement of his legitimacy. Perthes’ structural analysis attributed acquiescence largely to pressures for material survival. Footnote 121 Wedeen’s poststructuralist critique added that the regime’s “disciplinary-symbolic power” schooled citizens in public dissimilation. Both scholars concurred that conditions rendered “depoliticization,” “indifference,” and “cynical apathy” Syrians’ most salient political attitudes. Footnote 122 Wedeen’s later research on the Bashar era noted that some of that indifference became replaced with a neoliberal “aspirational consciousness” that produced stronger enthusiasm for the president.

These and other essential works go far in elucidating the complex multidimensionality of life in Assad’s Syria. Testimonials from Syrian rebellion supporters, however, suggest that they might have underestimated the role of simple fear in filling the “gap” between Syrians’ internal misgivings about their political system and their external submission to it. Correspondingly, fear, rather than depoliticization, was one of the most significant obstacles to protest for those who opposed Assad rule. As such, early protestors did not labor to convince fellow citizens to care about politics or even, primarily, to believe in their capacity to make a difference. Rather, those who joined the first demonstration in Daraa chanted, “No more fear!” Footnote 123 Oppositionists’ narratives suggest that political apathy might have been less a primary driver of behavior than a façade of fear. That is, subjected to silence, citizens might have transformed a degrading “personal thwarting”—which Theodore Kemper identifies as central to fear Footnote 124 —into the more tolerable detachment that outsiders observed as indifference. Further research can explore this and other questions as they use newly available self-expressive data to confirm or reconsider what we thought we knew about the lived experience of authoritarianism in Syria. This might show that apathy was just one of manifold ways of coping under Assad rule; the catalogue of “citizen survival strategies” was likely even longer than that of the “authoritarian regime survival strategies” that have received so much scholarly attention.

Second, descriptive analysis of testimonials offers a special window into identity. Narrative theories of identity propose that people come to be who they are and make sense of what has happened to them by locating themselves in stories. Footnote 125 Narratives of rebellion supporters illustrate how fear has been central in constituting their understanding of themselves as Syrians. Attention to their changing experience of fear can be a lens for gauging how their identities have evolved under the tumultuous conditions of the past years. No less, attention to variation in fear across Syrian society offers a rubric for comparing the heterogeneous identities that comprise it. Voices from social groups not represented in my interview sample—namely regime supporters—relay other fears, such as the apprehension that Assad’s fall will lead to chaos, loss of national sovereignty, Islamic fundamentalist takeover, or genocidal revenge. Footnote 126 Future research can explore how these fears are compatible with the typology that I outline, or perhaps amend it. Regardless, that many Syrians on opposing sides of the war share the experience of living politics through the prism of fear intimates a potential common ground that is lost in media emphasis on sectarian divides. Footnote 127 It suggests that enduring resolution to the current conflict might lie less in demographic formulas or territorial partition than in design of a political system in which no citizen is afraid. Observers who pronounce the demise of the Syrian nation-state ought not to discount the experience of political fear as something that binds Syrians, and the yearning to be free from fear as the starting point for the imagining of a new Syrian polity. Footnote 128

Finally, analysis of narratives illustrates how articulation of fear is itself a political process. Wedeen observed that Syrians’ repetition of regime rhetoric produces “acts of narration that are depoliticizing.” Footnote 129 No less, Syrians’ telling of their own stories produces new narratives that are both politicized and politicizing. In recounting how they cope with or defy fear, Syrians are deciphering the pressures and constraints that structure their environments, tracing the events that delineate their lives, and determining their paths as political agents. They are also refusing the collective silence that buttressed authoritarian rule for decades. This comes to light not only in my interviews, but in countless other examples of self-expression, as well. “I know this place will never be the same,” novelist Samar Yazbek wrote after nation-wide protests shook Syria on March 25, 2011. “Fear no longer seems as automatic as breathing.” Footnote 130 Others would pen similar observations. “Before Syrians’ battle was against their leaders, it was against fear,” writer Dima Wannous explained. Footnote 131 “No matter what happens now … Syria is already irreversibly, fundamentally changed. Syrians have found their voice,” an anonymous journalist asserted. Footnote 132 Another writer agreed: “Every drop of blood, every tear, every chant, every video, every tweet, every word … They are the sounds of our selves breaking free.” Footnote 133

The process of breaking free remains ongoing. To the degree that individuals continue to narrate the experiences undergirding that process, however, they help us understand the changing the nature of political authority, agency, and identity under tumultuous circumstances. Descriptive analysis of such data is especially valuable for investigation of authoritarian regimes unsettled by uprisings or war. Such cases are characterized both by new uncertainty in political conditions and new access to the voices of ordinary citizens. We should use the latter to help us make sense of the former. Listening to narratives from the field not only offers insight into how and why people revolt against oppressive rulers. It is also a chance to bear witness to rebellion in action.

Supplementary Materials

Online Appendix

-

General discussion on sampling

-

Identifying interviewees

-

Conducting interviews

-

Transcription and translation

-

Interpretive analysis

-

Data and confidentiality