Sights of soldiers patrolling urban neighborhoods, responding to reported crimes in progress, collecting evidence, and staffing checkpoints on major highways are increasingly common worldwide. Latin America, now the most violent region in the world, is no exception in the trend to militarize law enforcement. In Mexico, for example, more than 67,000 troops have participated in widespread policing operations since 2006 (Ordorica Reference Ordorica2011). In Brazil, the armed forces have helped state governments regain control of urban areas, with soldiers patrolling city streets on nearly 100 days in 2016 (The Economist 2017). In Honduras, the government created the Military Police for Public Order (PMOP) in 2013 to combat drug trafficking and close to 6,000 soldiers take part in joint army-police operations (Secretaría de Defensa Nacional de Honduras 2013). Even countries that historically have lacked a military, like Costa Rica and Panama, are considering proposals to militarize law enforcement.

The involvement of the region’s militaries in domestic security might have been common during military dictatorships, but it had been unusual in democratic regimes. While military regimes relied on their own cadre for internal policing or incorporated the police into the military’s repressive apparatus, as in Argentina, Chile, or Uruguay (Pereira Reference Pereira2005), contemporary democracies tend to have a separation between the roles of police (public safety) and military (national security)—a central element in civil-military relations conducive to civilian control over the military (Dammert and Bailey Reference Dammert and Bailey2005). As the evidence we present suggests, this distinction is increasingly less meaningful in Latin American democracies, where governments have militarized public safety and recast the role of the armed forces for domestic law enforcement purposes.

Despite the prevalence of militarized law enforcement, scholarly, policy, and journalistic attention has mostly focused on a fairly narrow form of militarization—namely when the police take on similarities to militaries—with a fairly narrow geographic range: the United States. Existing research has focused on the prevalence of SWAT teams with military-grade weapons in police departments across the United States (Balko Reference Balko2013; Kraska Reference Kraska2007), whether they have strained police-community relations (American Civil Liberties Union 2014) or had an effect on levels of violence (Delehanty et al. Reference Delehanty, Mewhirter, Ryan and Wilks2017).

While this research constitutes an important first step, it has neglected the prevalence and consequences of other forms of militarization taking place outside of the U.S. With that oversight in mind, we break ground by making five main contributions: 1) unpacking the concept of militarization of law enforcement to accommodate different forms; 2) developing theoretical expectations regarding its consequences in democratic contexts, 3) taking stock of the extent of militarization in Latin America, 4) evaluating whether theoretical expectations about its consequences have played out in the region, and 5) discussing the implications of obviating the lines between national security and public safety—what Tilly (Reference Tilly1992) characterized as external versus internal coercion. We argue that the distinction between civilian and military law enforcement typical of democratic regimes has been blurred in Latin America. We also show that the constabularization of militaries Footnote 1 has had important consequences in the region for citizen security, police reform, the legal order, and the quality of democracy more generally.

Scholarship on the Militarization of Law Enforcement

Inspired by scholarship from Huntington (Reference Huntington1957) and others on military organization and professionalization, toward the end of the 1970s the literature on civil-military relations in Latin America focused on the causes and consequences of military coups, as well as regime dynamics under bureaucratic-authoritarian rule (Fitch Reference Fitch1998; Hunter Reference Hunter1997; Norden Reference Norden1996; Remmer Reference Remmer1989; Stepan Reference Stepan1988). During the third wave of democracy, scholars continued to study civil-military relations with an eye towards the challenges of democratic consolidation and emphasizing civilian control over the military, coup proofing, and the armed forces’ role in regional security (e.g., Arceneaux Reference Arceneaux2001; Jaskoski Reference Jaskoski2013; Pérez Reference Pérez2015b; Pion-Berlin and Trinkunas Reference Pion-Berlin and Trinkunas2010; Rittinger and Cleary Reference Rittinger and Cleary2013). Footnote 2 In parallel, new scholarship emerged on the change in paradigm from national to citizen security, as well as the types and obstacles to police reform (Dammert and Bailey Reference Dammert and Bailey2005; Frühling Reference Frühling, Frühling, Joseph and Golding2003; González Reference González2017; Hinton Reference Hinton2006; Moncada Reference Moncada2009; Ungar Reference Ungar2011).

Despite the vast and rich literature on the military and police in Latin America, academic scholarship has remained relatively silent on the role of the armed forces in domestic security and on the blurring of the line between militaries and police forces under democratic regimes. Instead, recent literature on militarization of law enforcement has mostly adopted a U.S.-centric approach. Most of it corresponds to journalistic accounts drawing attention to the nationwide trend of militarization of local police departments, but several academic studies have documented the adoption of military equipment and tactics by civilian police under the Department of Defense’s 1033 Program (Balko Reference Balko2013; Kraska Reference Kraska2007).

Some authors have equated militarization of police in the United States with better training, discipline, and accountability (Wood Reference Wood2015). A strand of research (den Heyer Reference den Heyer2013) even characterizes the militarization of police as part of a “natural progression in the evolution and professionalization of … policing” (p. 347). Others are less sanguine about the consequences of militarizing the police, finding that the 1033 Program contributes to a higher number of fatalities from officer-involved shootings (Delehanty et al. Reference Delehanty, Mewhirter, Ryan and Wilks2017), undermines police-community relations (Bickel Reference Bickel2013), and fails to enhance officer safety or reduce local crime (Mummolo Reference Mummolo2018).

To the extent that the “police-icizing” or constabularization of the military has been studied, it has been in the limited contexts of U.S. military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq (Kraska Reference Kraska2007) or indirectly as a byproduct of U.S. anti-drug policies during peacetime (Youngers Reference Youngers2000). Whereas existing research has mostly focused on the financial and training assistance that the U.S. military has provided abroad (Youngers Reference Youngers, Youngers and Rosin2004; Isacson and Kinosian Reference Isacson and Kinosian2017) or on rich, country-specific descriptions (Moloeznik and Suárez Reference Moloeznik and Eugenia Suárez2012; Zaverucha Reference Zaverucha2008), the systematic study of the consequences of the most extreme form of militarization—constabularized soldiers—remains scarce. Notable exceptions include Pion-Berlin’s research (2017) on differences in military missions in Mexico and Arana and Ramírez’s (Reference Arana and Ramírez2018) and Trujillo Álvarez’s (Reference Trujillo Álvarez2018) studies on re-militarization in Central America.

Although existing scholarship provides a valuable point of departure, we move forward this relatively underdeveloped research agenda by: 1) defining and developing the concept and types of militarized law enforcement; 2) drawing theoretical expectations for the consequences of militarizing public safety for the quality of democracy regarding citizen security, human rights, police reform, and the legal order; 3) taking stock of militarization in Latin America; and 4) assessing whether theoretical expectations have played out in the region, with an emphasis on the highest degree of militarization: constabularization.

Conceptualizing the Militarization of Law Enforcement

Kraska (2007, 3) defines militarization of police as “the process whereby civilian police increasingly draw from, and pattern themselves around, the tenets of militarism and the military model.” While this definition might reflect the U.S. experience, it does not account for the experience beyond its southern border, where the armed forces themselves conduct law enforcement tasks previously reserved for civilian police.

To address this, we go up Sartori’s (Reference Sartori1970) ladder of abstraction by introducing the concept of “militarized law enforcement,” which can in turn comfortably accommodate different sub-types beyond civilian police. We define militarized law enforcement as the process through which government agencies tasked with providing public safety adopt the weapons, organizational structure, and training typical of the armed forces. This broader definition includes not only civilian police that pattern themselves like militaries (as Kraska’s definition implies), but also paramilitary forces and constabularized soldiers providing domestic public safety.

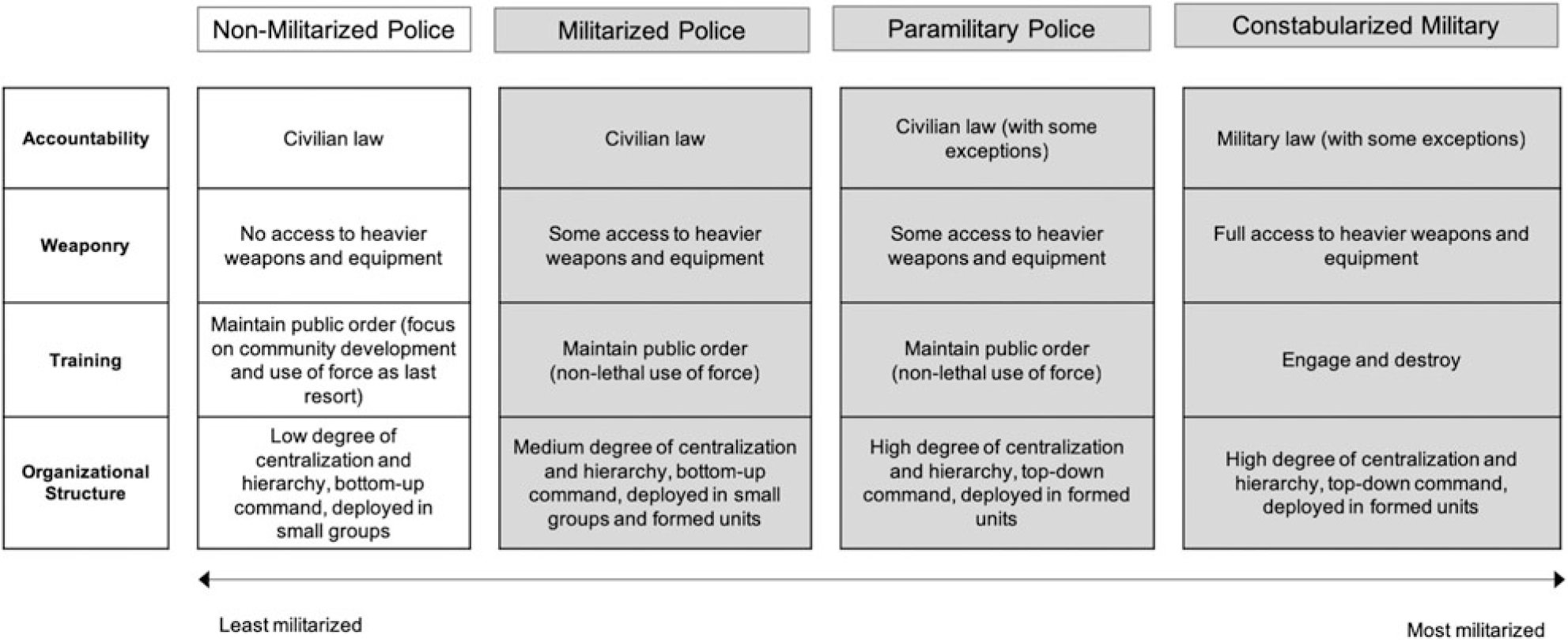

The different types of militarized law enforcement form a continuum in practice (refer to figure 1). On the non-militarized end of the spectrum, civilian police report to a civilian authority and are under the jurisdiction of civilian law. They are trained to use force as a last resort, follow a serve-and-protect directive, tend to be organized in low hierarchy structures, and often focus on community-oriented policing.

Figure 1 Law enforcement types based on degree of militarization

The second type is militarized police, which share some features of their non-militarized counterparts, such as the civilian jurisdiction and low-hierarchy structure, but also rely on some military-grade weapons and gear, military-style formations, and tactics. Examples include the proliferating SWAT teams in local law enforcement in the United States and immediate-reaction units in national and local police forces in Latin America.

The next type moving toward the most-militarized end is the paramilitary police. Though one cannot find a standard gendarmerie-style force, paramilitary forces more organically incorporate practices typical of the armed forces. Although they preserve the non-lethal use of force as their main modus operandi, maintain a serve-and-protect mentality, and are in most cases under the jurisdiction of civilian law, they rely on military weapons and gear, have a more hierarchical structure, operate based on military deployment tactics and units, and some might even report to the Ministry of Defense. Examples include Chile’s Carabineros, Brazil’s Polícia Militar, Spain’s Guardia Civil, and France’s Gendarmerie Nationale.

In the most extreme form of militarization of law enforcement, the armed forces take on public safety tasks themselves, including crime prevention (security patrols); crime fighting (drug crop eradication and interdiction, drug and arms seizures, searches and arrests, evidence gathering and interrogation); and prison security. Constabularized militaries report to the Ministry of Defense, operate under military law, follow a strict hierarchical structure, have full access to the most destructive weapons, and are trained according to an engage-and-destroy directive. Examples of constabularized militaries are the Peruvian armed forces during part of Alberto Fujimori’s rule, and the semi-permanent crime-fighting operations across the national territory by Honduran and Mexican armed forces, among others.

Given that there is no single model for any of the four different types, there may be differences across countries. For example, paramilitary police may be under the Ministry of Defense in some countries but a Ministry of Public Safety or the Interior in others. Additionally, seldom do countries rely on a single type of law enforcement. Rather, depending on the legal framework, multiple types can operate simultaneously (e.g., non-militarized municipal police and militarized state police).

Regional Drivers of Militarization

The militarization of law enforcement in the region has mainly responded to rising levels and violent nature of crime, the appeal of punitive populism amid perceptions of police incompetence and corruption, and incentives created by U.S. foreign policy. Footnote 3 First, with 2.6 million homicides between 2000 and 2016 (Marinho and Tinoco Reference Marinho and Tinoco2017), Latin America is today the most unsafe area in the world outside of a war zone. The deterioration of public safety has been precipitous in places such as El Salvador, Mexico, and Venezuela, where homicide rates doubled or tripled in short periods of time. Not surprisingly, addressing crime has become the number one public concern in most countries in the region (Latinobarómetro 2015).

Organized crime’s levels of sophistication, brutality, and resources have prompted governments to militarize public safety. Criminal organizations in Latin America increasingly rely on weapons typically reserved for militaries, as well as on cutting-edge technology for communication and transportation. The cross-border nature of their operations and their seemingly unlimited resources to bribe officials have changed considerably the tactical power of criminal organizations vis-à-vis civilian law enforcement, which are often poorly paid, trained, and equipped.

Second, punitive populism—when leaders appeal to tough-on-crime approaches for electoral gain—has been fueled by perceptions of incompetence and corruption of civilian police agencies. Compared to the police, militaries are often perceived as more competent, less prone to corruption, and more inclined to put the interests of the country first. The armed forces enjoy greater trust than the police in all but two countries—Chile and Uruguay—where support is roughly the same (Americas Barometer by the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) 2014).

These perceptions have become political incentives that lead to punitive populism, which has increased the role of the armed forces in domestic security. Rather than investing in the more difficult task of strengthening civilian law enforcement institutions—a protracted process often requiring legislative negotiations—an electorally flashy and easily accessible alternative for executives has been to rely on the armed forces. By tapping into fear of crime, such actions have broad cross-class appeal regardless of their effectiveness.

Third, U.S. anti-drug policy abroad has contributed to the constabularization of the military in Latin America. Although the U.S. military is generally barred from participating in domestic law enforcement activities, Footnote 4 it has been fairly active in the region (Weeks Reference Weeks2006). Military assistance has taken the form of funding toward weapons, equipment, training, construction of military bases, and monitoring and interdiction of drug trafficking. In total, between 2000 and 2016 the U.S. Department of Defense provided Latin American and the Caribbean over US$5.5 billion in security aid (Security Assistance Monitor 2017). This aid is often tied to military equipment—such as Blackhawk and Apache helicopters—provided as in-kind assistance for anti-drug efforts. The number of special operations forces training missions to Latin America tripled between 2007 and 2014, and the U.S. currently works with the security forces of all countries in Latin America except Cuba, Venezuela, and Bolivia (Isacson and Kinosian Reference Isacson and Kinosian2017). Overall, the assistance toward the armed forces’ drug eradication and seizures far exceeds the money invested in helping states strengthen civilian institutions (Isacson and Kinosian Reference Isacson and Kinosian2017).

Theorizing the Consequences of Constabularization

Having unpacked the different types of militarization of law enforcement and discussed its drivers in the region, we turn to developing theoretical expectations about political consequences. In particular, we expect differences along four dimensions—accountability, weaponry, training, and organizational structure—to have important consequences for key features of democratic governance: citizen security, human rights, police reform, and the legal order. Footnote 5 Although we expect their consequences to intensify and become more prevalent as the degree of militarization increases, we give special consideration to the consequences of the most extreme type: constabularized militaries.

First, the heavy weaponry, combat training, and tactical organization and deployment that come with militarization will translate into greater disruptive capacity. Since these features of militarization are meant to maximize destructive power, militarized personnel will be more likely than non-militarized counterparts to use excessive force. For example, levels of violence will increase as the type of law enforcement moves away from traditional service weapons—such as Glock pistols—and closer to military weapons—such as submachine guns and assault rifles. Combat training meant to eliminate enemies rather than arrest suspects will also result in greater violence. The centralized, hierarchical organization characteristic of militaries will make personnel all the more effective at maximizing disruption. These features of militarized units, which generate greater destructive capacity, will result in larger numbers of casualties and wounded as the degree of militarization increases.

In the case of constabularized militaries, the combination of military weapons, training based on an engage-and-destroy mentality, and a centralized, hierarchical organization will result in the greatest disruptive capacity conducive to intensifying violence. As Lawson (2018, 1) notes, security personnel enjoy a lot of discretion in “deciding how to handle the situations they encounter.” Given their highly hierarchical structure and centralized management and decision making, involving the armed forces in law enforcement increases the distance (both social and physical) between communities and security personnel, which makes the military more likely to use force compared to civilian law enforcement counterparts that are embedded in the communities (Lawson Reference Lawson2018).

Further, not only will more destructive weapons, training, and organization lead to more wounded and deaths in discretionary contexts, but they will also escalate violence by creating incentives for organized crime to fight back and respond in kind (Lessing Reference Lessing2017; Osorio Reference Osorio2015). Because militarized features result in a greater disruptive capacity, constabularized militaries’ actions will encourage the greatest backlash from organized crime—a rational survival strategy that results in tit for tat escalation, as Lessing (Reference Lessing2013, Reference Lessing2017) has shown in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico. Holding the will to enforce the law constant, militaries’ greater disruptive capacity compared to police will elicit a more violent reaction from organized crime.

Second, in the high-risk, highly-discretionary contexts typical of law enforcement, the greater disruptive power that comes with greater militarization will be conducive to more human rights violations—including warrant-less searches, illegal detentions, torture, and extra-judicial killings. Whereas non-militarized police are trained with an emphasis on developing relations with the community, de-escalating conflict, and exercising restraint on the use of force, constitutional protections will be more difficult to uphold as law enforcement personnel move away from this directive and closer to overwhelming and eliminating an enemy (Dunlap Reference Dunlap1999).

In the most extreme form of militarization—constabularization—military-style training and capacity will make security personnel more prone to treating suspected criminals as a threat to their survival and reacting violently—even in situations that do not require the lethal use of force (Dunn Reference Dunn2001). The centralized, hierarchical organizational structure typical of the military leaves more room for abuse because of the physical and psychological distance they generate vis-à-vis citizens (Willits and Nowacki Reference Willits and Nowacki2014). This does not mean that non-militarized personnel are always respectful of human rights, but that the armed forces’ greater disruptive capacity will result in a comparatively higher prevalence of human-rights abuses.

Third, reforming the less militarized agencies will become harder as the type of law enforcement moves away from non-militarized police and toward constabularization. Because of their popularity among the public and political expediency, Footnote 6 more militarized forms of law enforcement reduce incentives for police reform. Widespread support for tough-on-crime policies increase electoral incentives to further militarization while reducing incentives for channeling necessary resources toward reforming the police (González Reference González2017; Moncada Reference Moncada2009, 432).

In the case of constabularization, the military’s greater disruptive capacity conveys the impression of competence at providing public safety (Bitencourt Reference Bitencourt, Tulchin and Ruthenburg2007; Flores-Macías and Zarkin Reference Flores-Macías and Zarkin2019). Because of constabularization’s popularity, leaders withdrawing the armed forces from the streets come across as soft on crime and risk paying an electoral penalty. Conversely, institution-building of civilian law enforcement agencies does not lend itself to quick public relations gains. Instead, police reform tends to be slow-moving and technically difficult, and requires sustained political commitment, cooperation across party lines, and between national and local authorities. Because of these political incentives and the low hurdles executives face for deploying the military, governments will tend to allocate resources toward military budgets to strengthen domestic public safety, even if non-militarized law enforcement are in desperate need of reform. In short, although constabularization is in part a consequence of ineffective and unreformed police, once adopted, constabularization in turn reduces the incentives for police reform.

Fourth, as the type of law enforcement moves away from civilian legal jurisdictions and becomes subject to military law, the legal framework will less-comfortably accommodate the armed forces’ domestic policing in a democracy (Amnesty International 2017; Dunlap Reference Dunlap1999). In the absence of laws that regulate the military’s domestic law enforcement tasks, militaries in some countries will operate without clearly defined legal boundaries. This can undermine the rule of law and contribute to a sense of impunity whenever the armed forces engage in violations of constitutional protections. While constabularization within the scope of the law provides greater legal certainty to the armed forces’ domestic actions, rarely is the domestic conduct of soldiers as fully and clearly regulated as police action in democratic contexts, especially those with weak institutional settings as in Latin America.

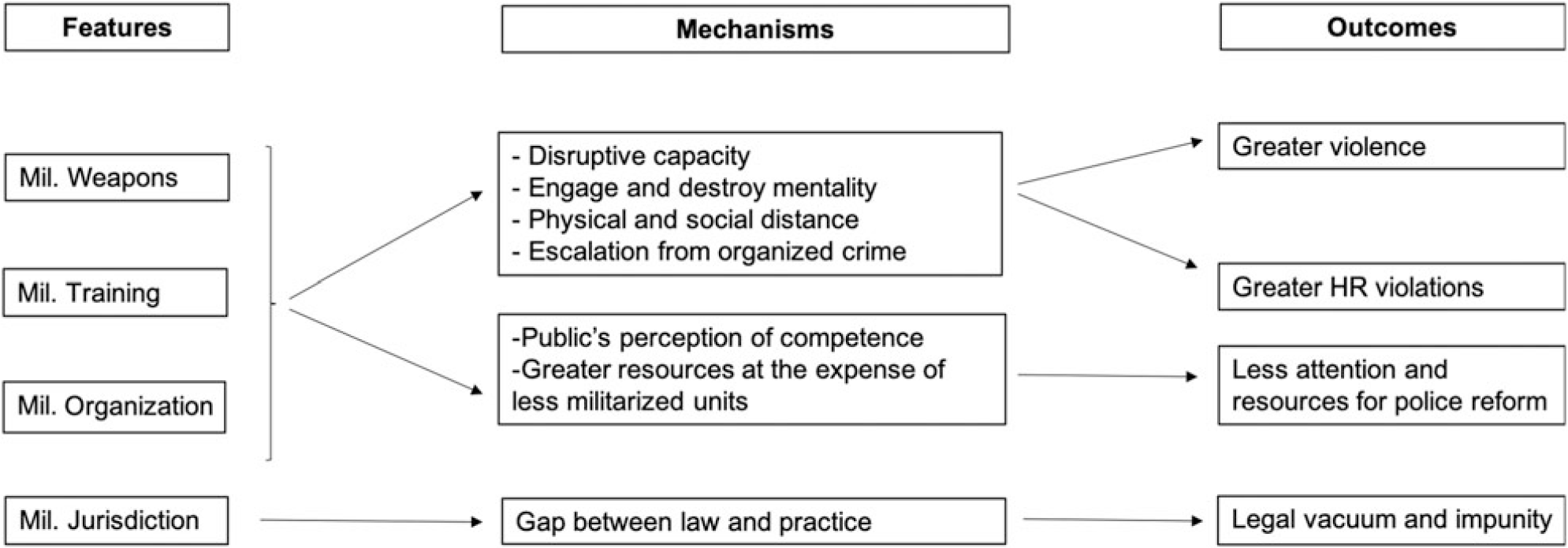

In short, as shown in figure 2, we expect higher levels of violence, greater human rights violations, more difficulty in reforming non-militarized police, and a greater disconnect between law enforcement and the legal framework as the degree of militarization increases. Constabularized soldiers will be more likely to elicit these outcomes than paramilitary police, and they will in turn be more likely among paramilitary police than less-militarized counterparts. Even when units with different degrees of militarization are deployed jointly—e.g., soldiers alongside federal police—we can expect these differences to play out, since their disruptive capacities are different, as are the legal frameworks that regulate their conduct.

Figure 2 Theoretical expectations for increased militarization

Taking Stock of the Militarization of Law Enforcement

We now turn to evaluating these hypotheses about the consequences of militarization based on evidence from Latin America. The first step is to determine the extent to which the phenomenon has taken place in the region, excluding cases of counterinsurgency because historically this has been a task generally reserved for the armed forces. We classify countries based on the highest level of militarization of law enforcement operating within its territory, although in most cases several law enforcement types co-exist (figure 3). For the extreme case of constabularization of the military, we make a distinction between cases of limited constabularization—countries where militaries have performed law enforcement functions in narrow geographic areas for short periods of time—and generalized constabularization—where the armed forces have carried out those functions in a sustained fashion across the national territory. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic effort to take stock of militarization in Latin America.

Figure 3 Highest degree of militarized law enforcement by country

Note: Generated by the authors. See appendix for sources.

Non-Militarized Police

Although examples of non-militarized police remain in the region at the subnational level, as is the case in local or municipal law enforcement, at the national level there is no country that relies exclusively on this type of police. In all countries, national police rely on tactical units with military training, as well as assault weapons, Humvees, and other military gear for their routine daily operations. Even in Costa Rica, where the 1949 Constitution abolished the armed forces, units with military training exist since at least 1983, especially within the Dirección de Inteligencia y Seguridad, which reports directly to the president (González Reference González2008).

Militarized Police

Only two countries in the region rely exclusively on militarized civilian police: Costa Rica and Panama, neither of which has a military. Having abolished its army in 1948, Costa Rica relies on its civilian Fuerza Pública for law enforcement purposes, including crime prevention and investigation, arrests, border control, and prison management. In Panama, the civilian National Police has carried out these functions since the 1989 U.S. military intervention. Additionally, special operation forces like the Antinarcotics Special Forces (FEAN) in Panama and the Unidad Especial de Intervención and Fuerza Especial Operativa in Costa Rica are militarized police units in charge of maintaining public order.

Paramilitary Police

Argentina, Footnote 7 Chile, and Uruguay primarily rely on paramilitary style police forces and have generally refrained from engaging the military in policing activities. In Argentina, the main law enforcement forces are the Federal Police, the Airport Security Police, and the Provincial Police, as well as two paramilitary forces: the National Gendarmerie and the Naval Prefecture. Although the military has provided logistical and technological assistance under joint operations near the borders such as the Operativo Combinado Abierto Misiones (De Vedia Reference De Vedia2016), these civilian police and paramilitary agencies remain in charge of crime-fighting activities such as drug and arms seizures and surveillance (Telam 2017). In Chile, the Carabineros are the paramilitary force legally tasked with the country’s internal law enforcement, including crime prevention, crime fighting, and prison security. Although they had been under civilian control on and off throughout the twentieth century, they remain under civilian control in the Ministry of the Interior since 2011. In Uruguay, president José Mujica (2010‒2015) combined existing forces—including the anti-riot police (Guardia de Granaderos) and the SWAT team (Grupo Especial de Operaciones)—in 2010 to create the paramilitary police Regimiento Guardia Nacional Republicana (Porfilio Reference Porfilio2015). This gendarmerie-style force is engaged in crime prevention, crime fighting, and prison security (El País 2016).

Limited Constabularization of the Military

Four countries in the region involve their militaries in geographically limited law enforcement operations: Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, and Peru. While their governments rely on the armed forces to address drug trafficking and organized crime, military operations tend to be restricted geographically and temporally. In Paraguay, the National Police have generally led efforts to address organized crime, including drug interdiction and drug crop eradication since president Andrés Rodríguez created the National Anti-Drug Secretariat (SENAD) in 1992 (U.S. Department of State 2015). However, beginning with Fernando Lugo’s administration (2008‒2012), governments have at times assigned the armed forces to domestic law enforcement. In particular, the military’s Fuerzas Especiales have participated in SENAD’s anti-drug activities, especially in the areas of Amambay, Concepción, and San Pedro, during the presidency of Horacio Cartes (2013‒2018). Footnote 8

In Peru, the armed forces have been involved intermittently in domestic law enforcement since Alberto Fujimori’s authoritarian rule, especially in areas where Shining Path has been thought to operate. Since 2003, governments have declared the Valley of the Apurímac, Ene, and Mantaro Rivers (the VRAEM region in Spanish), where 70% of Peru’s cocaine is produced, as emergency zones and given the armed forces control over the internal security of the region (Jaskoski Reference Jaskoski2013). In 2016 and 2017 president Pedro Pablo Kuczynski renewed the states of emergency in the several districts of Huancavelica, Ayacucho, and Cuzco (La Razón 2016) and VRAEM region (El Peruano 2016; Perú21 2017) to deploy the armed forces against drug trafficking.

In Bolivia, the armed forces have participated in domestic law enforcement in three broad areas: maintaining internal political order, fighting drug trafficking, and providing citizen security. President Evo Morales (2006‒present) temporarily increased the military’s involvement: on and off since 2009, more than 2,000 members of the armed forces have participated in joint military-police patrols and arrests under Plan Ciudad Segura in cities like La Paz, El Alto, Cochabamba, and Santa Cruz (Ministerio de Defensa de Bolivia 2012). In addition to participating in urban policing, the armed forces have been involved in efforts against contraband activity and drug crop eradication operations in the Cochabamba tropics, los Yungas, and the national parks.

In Brazil, every president has deployed the military to address violence in Rio de Janeiro since the federal government sought to regain control of 20 to 30 favelas in Operation Rio (November 1994‒January 1995) (Donadio Reference Donadio2016). Footnote 9 Recent interventions include the participation of up to 40,000 members of the national army in border security (Agatha Operations) starting in 2011, the temporary occupation of Rio’s favelas in 2014-2015 (Garantia da Lei e da Ordem missions), and the control of public demonstrations, strikes, and prison riots—including president Michel Temer´s (2016‒2018) deployment of troops to the streets of Brasilia to quell protests against him in May 2017 and authorization for the army to take control of public security in Rio de Janeiro in February 2018.

Generalized Constabularization of the Military

In nine countries the armed forces are involved in sustained law-enforcement tasks across the national territory. Excluding counter-insurgency operations, in Colombia the armed forces have been involved in internal order since the 1960s (Leal Buitrago Reference Leal Buitrago2004). In 1998, Andrés Pastrana (1998‒2002) created the First Battalion Against Drug-Trafficking, later institutionalized as the Army’s Counternarcotic Brigade, which led aerial and manual eradication operations, drug seizures, and the destruction of laboratories. By the time Plan Colombia was adopted in 1999, the number of domestic military operations to address drug trafficking reached 977 in 2005 (Schultze-Kraft 2012). In 2011, the Fourteenth Directive from the Ministry of National Defense involved the military in the fight against organized crime (known as BACRIM), through joint operations with the National Police (Llorente and McDermott Reference Llorente, McDermott, Arnson and Eric2014). For example, Operation Troy involved 1,000 members of the National Police and 3,000 soldiers in the Caucasia area (McDermott Reference McDermott2011). Despite the 2016 peace accord with the FARC, the government continues to employ the military in fighting drug trafficking and contraband. Currently 300,000 members of the armed forces work in citizen security activities throughout the country, of which 60,000 have been deployed under Plan Victoria to occupy the former FARC zones of influence (160 municipalities) (Noticias de América Latina y el Caribe 2017).

In the Dominican Republic, the armed forces have participated in repeated operations in urban areas and in joint army-police operations that include security checkpoints, patrolling, and vehicle searches since 2001. In 2013 the Federal Government launched the Plan of Internal and Citizen Security Operations led by the recently created Comando Conjunto Unificado (Donadio Reference Donadio2014). Since then, 2,000 soldiers have participated in joint army-police patrols in several of the country’s main cities, including La Altagracia, San Cristóbal, Santiago de los Caballeros, and Santo Domingo (Paniagua Reference Paniagua2017).

In Ecuador the armed forces’ involvement in domestic law enforcement went from sporadic to semi-permanent. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, Ecuadorian presidents Jamil Mahuad, Gustavo Noboa, and Alfredo Palacio signed executive decrees that allowed the armed forces to temporarily take over security measures in several provinces, including the city of Quito. In 2010 president Rafael Correa (2007‒2017) increased the number of operations and tasks involving the armed forces. Under his 2011 Plan Nacional de Seguridad Integral and the Política de Defensa, the armed forces participated alongside the National Police in domestic law enforcement (Ministerio de Coordinación de Seguridad de Ecuador 2011). In 2011, for example, the military participated in 30,710 crime fighting operations including drug interdiction and arrests, such as Operativo Relámpago (Grupo de Trabajo en Seguridad Regional 2013, 5). In 2014, 52,355 such operations took place in El Oro, Guayas, and Imbabura, among other provinces (Cordero Reference Cordero2014).

In El Salvador, the military played a supporting role in patrols between the 1992 Peace Accords and 2002, but increased its involvement in domestic security afterwards (Aguilar Reference Aguilar2016). Between 2003 to 2006, with Plans Mano Dura (2003) and Súper Mano Dura (2004), they became directly involved in seizures and arrests through joint police-military groups (Grupos de Tarea Antipandilla) and military-only units (Fuerzas de Tarea). Since 2009, the military has also conducted operations related to car theft prevention, arms smuggling, human trafficking, drug trafficking, protection of bus routes and school perimeters, and prison security. Between 2009 and 2014, more than ten specialized groups among the armed forces were created to combat organized crime. Footnote 10 Today, an estimated 39% of El Salvador’s armed forces participate in domestic law enforcement missions: 2,940 in citizen security; 2,575 in the prison system; and 580 in border security (Pérez Reference Pérez2015a).

Although the 1996 Peace Accords ending Guatemala’s civil war led to the creation of the Civilian National Police (PNC), two years later the military began participating in joint operations with the PNC. Since the creation of the Joint Security Force (4,500 soldiers and 3,000 police) in 2000, the military took the lead in the country’s internal security, with the number and types of missions, number of troops, and areas patrolled increasing steadily. President Otto Pérez Molina (2012‒2015) increased the number of domestic security missions assigned to the armed forces—over 116,000 in 2014 alone (Ministerio de la Defensa Nacional de Guatemala, 2014)—and created Fuerzas de Tarea and Special Reserve Corps for Citizen Security. Both forces are assigned to citizen-security tasks including patrolling, checkpoints, raids, highway security, and security patrols to prevent armed attacks on mass transit buses and public schools (Ministerio de la Defensa Nacional de Guatemala 2014). Footnote 11

In Honduras, the armed forces have increasingly participated in domestic law enforcement since Ricardo Maduro’s administration (2002—2006). During his presidency, the armed forces participated in joint operations with police in a small number of municipalities, such as 2003 Operación Libertad, in which 1,000 police and soldiers were ordered to patrol the streets of Tegucigalpa, or in 2004 when over 1,500 police and soldiers travelled aboard city buses to protect the drivers from extortion and violence. The military’s involvement in internal security grew considerably during Porfirio Lobo’s administration (2010‒2014), with over 7,000 soldiers participating every year in public-safety operations throughout the country. Alongside the increase in operations, his government created the Military Police for Public Order in 2013, which is a security task force of nearly 5,000 armed forces with the mission of helping the National Police to maintain order (Poder Legislativo de Honduras 2013). Under president Juan Orlando Hernández (2014‒present) the armed forces participate in an average of 300,000 domestic public safety missions each year (Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional de Honduras 2016).

Although the Mexican armed forces were involved sporadically in drug crop eradication missions throughout most of the twentieth century, by 1998 about 23,000 military personnel participated in anti-drug tasks on a daily basis (Mendoza Reference Mendoza2016, 26). Continuing with this trend, president Vicente Fox’s 2005 Operativo México Seguro involved 18,000 military personnel in drug eradication and capturing kingpins (Mendoza Reference Mendoza2016). However, in December 2006 Felipe Calderón’s (2006‒2012) declaration of all-out war against drug traffickers marked the start of the military’s protracted law enforcement operations in large parts of the territory to address not only drug trafficking but also organized crime more generally. Over 67,000 soldiers work permanently fighting criminal groups in at least twenty-four of the thirty-two Mexican states (Angel Reference Angel2016).

The Nicaraguan military’s law-enforcement tasks primarily take place in most of the countryside, patrolling highways, protecting the coffee harvest, and preventing cattle theft. Beginning in the 1990s, each year during the months of November to February, the military has participated in the Plan de Protección a la Cosecha Cafetalera, which includes joint army-police patrols of the coffee-growing fields. Since 2016, under the Plan Permanente de Seguridad en el Campo, the military maintains a permanent involvement in patrolling, checkpoints, highway security, operations of interdiction, confronting and arresting criminals. In that year, it participated in 92,416 missions in the departments of Boaco, Chontales, Jinotega, Matagalpa, and Rivas (Ejército de Nicaragua Reference Ejército2016).

In Venezuela, the 1999 Plan Nacional de Seguridad Ciudadana involved the armed forces in maintaining internal order and combating organized crime. President Hugo Chávez (1999‒2013) further increased the armed forces’ involvement in law enforcement through Plan Confianza in 2001, Plan Seguridad Ciudadana Integral in 2003, and Plan Caracas Segura in 2008. In 2009 he created DIBISE (Dispositivo Bicentenario de Seguridad), which involved 1,200 National Guard personnel in flashy operations in crime-ridden neighborhoods. The plan also created public safety commands in each state, led by the National Guard. In 2013, president Nicolás Maduro repackaged DIBISE into Plan Patria Segura, which also tasked the armed forces with setting up security checkpoints and patrolling the streets (Donadio Reference Donadio2014). Footnote 12

Evaluating the Consequences of Militarization

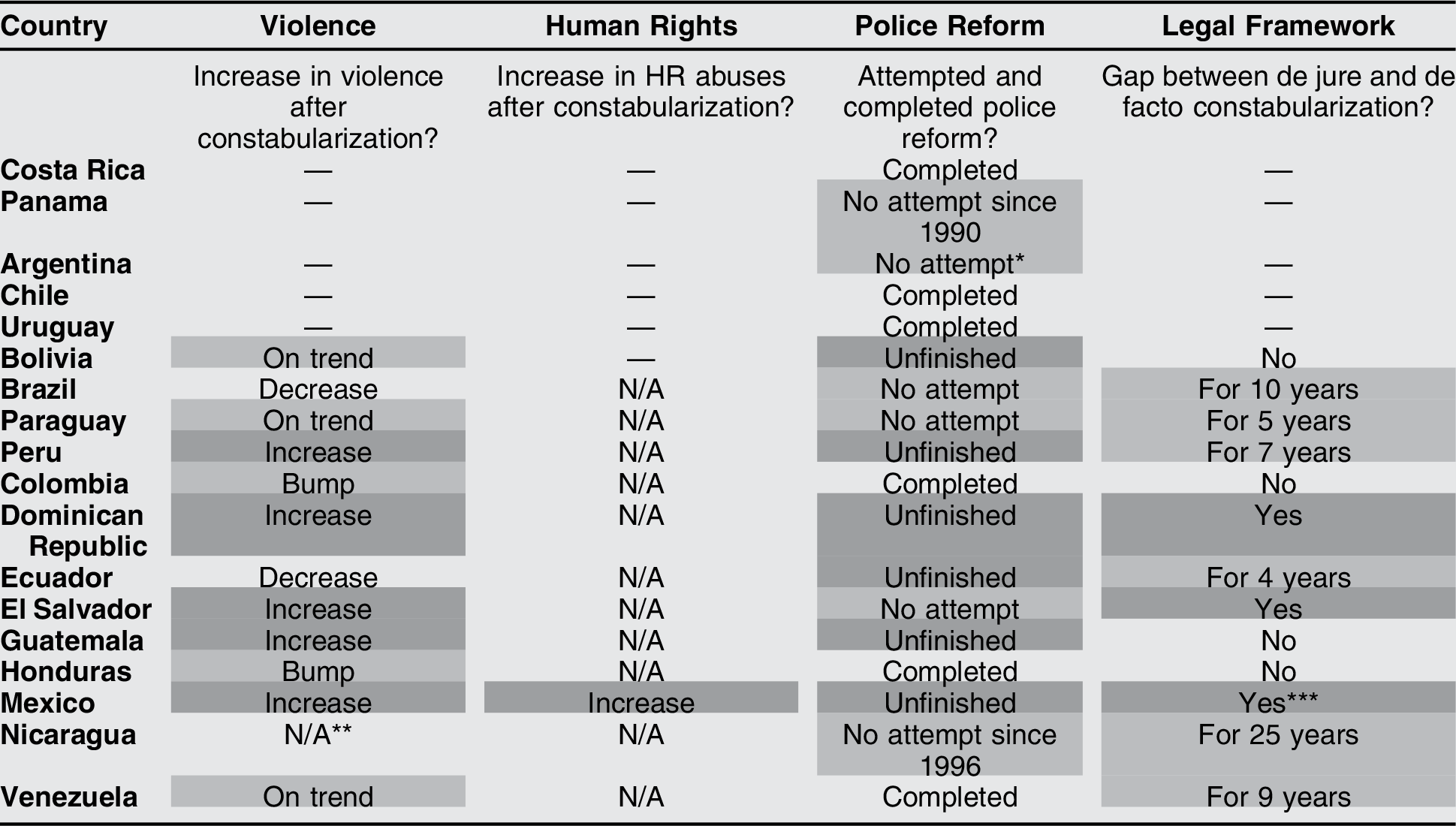

Having determined the extent to which the different types of militarized law enforcement are present, we evaluate whether the theoretical expectations play out in the region. As a first approximation, table 1 shows the extent to which there is cross-national evidence for the main consequences discussed in the theory section. Since different types of law enforcement co-exist in most countries, we emphasize the consequences of constabularization in the empirical analysis because its extreme nature helps uncover the effects of militarization. More generally, however, we expect the theorized consequences of militarization to become more prevalent in countries with higher degrees of militarization.

Table 1 Consequences of constabularization by country

NB: Refer to the online appendix for sources and coding criteria.

* Argentina is conservatively coded as no attempt, but the main subnational police department, the Buenos Aires Police, completed successful reforms in the late 1990s.

** Nicaragua is coded as N/A because the available data begins after constabularization

*** In Mexico a 2019 National Guard law granted the president temporary power to deploy the armed forces for public security purposes under extraordinary situations until the National Guard is fully operational.

Recognizing the generalized lack of data and difficulty in establishing systematic indicators that work across contexts, as well as the fact that militaries are often called on to operate in more challenging environments to begin with—i.e., they are not randomly deployed—the criteria used for this initial evaluation are simple: whether constabularization preceded any increases, bumps, decreases, or no change in levels of violence and human rights complaints, whether police reform at the national level was attempted and completed (regardless of effectiveness), and whether constabularization has taken place outside of the prevailing legal order. Table 1 reflects this coding across countries with the exception of human rights violations, since most countries lack yearly data on human rights complaints against the military that can be evaluated systematically. The exception is Mexico, which is included in table 1. Although yearly data for human rights violations are not available for the cross-national evaluation, a regional discussion follows and further subnational evidence from Mexico is presented in the next section.

Levels of Violence

As table 1 suggests, temporary or sustained increased levels of violence followed in six of the nine countries that adopted generalized constabularization. Ecuador (decrease) and Venezuela (on trend) are cases in which constabularization did not precede sharp increases in the homicide rates, and in Nicaragua constabularization preceded the available data. Among the cases of limited constabularization, where the military operated in limited regions and periods of time, the evidence is mixed (with one increase, two on trend, and one decrease, out of four).

The trends in homicide rates shown in table 1 are supported by country-specific accounts regarding the consequences of militarization. Although the armed forces tend to be assigned to more difficult situations than other forms of law enforcement, making it difficult to assess whether they contribute to increased violence, the timing of militarization is consistent with surges in the adoption of tough-on-crime measures. In El Salvador, for example, spikes in homicide rates have followed constabularization under plans Mano Dura and Súper Mano Dura (García Reference García2015). In Honduras, a temporary sharp increase in violent crime took place following constabularization with Operation Freedom in 2003, and another one followed by a surge in troop deployments in 2007. In Mexico, although many factors can contribute to increases in violence, systematic studies suggest constabularization is at least partly responsible for increased violence (Flores-Macías Reference Flores-Macías2018; Merino Reference Merino2011; Osorio Reference Osorio2015).

Human-Rights Violations

Although human rights complaints filed against the armed forces are mostly absent from table 1 given the lack of standardized data for all but one Latin American country, available reports suggest that respect for human rights has deteriorated whenever more militarized forces have become involved in law enforcement. Across the region, constabularized militaries have been prone to conducting extra-judicial executions, crime scene manipulation, warrant-less searches, arbitrary arrests, and enforced disappearances.

Contrary to the view that militaries tend to be more professional than police departments and that their training makes them more respectful of civil liberties (den Heyer Reference den Heyer2013; Wood Reference Wood2015), reports of extra-judicial killings conducted by soldiers are widespread. Because of their greater disruptive capacity, soldiers’ violations tend to be of greater magnitude—often leading to not only disappearances, torture, and arbitrary arrests, but even veritable massacres.

For example, in Venezuela, a human rights NGO (PROVEA), has documented over 700 extrajudicial killings during the Operaciones de Liberación y Protección del Pueblo (Unidad Investigativa sobre Venezuela 2016). In Honduras, there is evidence of military death squads with hit lists (Lakhani Reference Lakhani2017). Reports also document extrajudicial killings in Colombia—with close to eight hundred soldiers convicted and sixteen generals investigated between 2002 and 2008 (Human Right Watch 2015)—and in Guatemala (Plaza Pública 2012). In Mexico, the military have been implicated in a number of massacres—including Tlatlaya in the state of Mexico (refer to the online appendix for Mexico’s human-rights trends). In El Salvador, the Plan Mano Dura and Plan Súper Mano Dura resulted in the arbitrary arrests and disappearance of thousands of young adults believed to be part of gangs (Holland Reference Holland2013). In Honduras, the National Human Rights Commission (CONADEH) has documented torture, kidnapping, and sexual violence perpetrated by the military (Human Rights Watch 2016).

Although systematic regional data is not available, country-specific reports suggest the armed forces have been responsible for widespread abuse wherever they operate. Given the high levels of impunity that characterize the region, and the generally opaque military tribunals that often have jurisdiction over soldiers’ actions, holding the armed forces accountable for these violations remains an elusive task.

Police Reform

A reason governments cite for involving the armed forces is that doing so buys time in order to strengthen civilian law enforcement institutions: while the military provisionally address drug-trafficking, the government can (in theory, although rarely in practice) work on professionalizing the police and rooting out corruption (den Heyer Reference den Heyer2013). This is the rationale behind Guatemala’s gradual adoption of Plan of Operativización in 2017, Mexico’s purge of municipal police forces, and Venezuela’s creation of the new National Police and the Police University (UNES) between 2009 and 2013 (Hanson and Smilde Reference Hanson and Smilde2013), for example.

Although there is variation in the extent of police reform, reforms have generally taken place among countries with no or partial constabularization. Conversely, with the exceptions of Colombia, Honduras, and Venezuela, countries with constabularized militaries have either struggled to carry out police reform or have not attempted reform in spite of needing it. For example, in Ecuador the involvement of the armed forces by decree contributed to the neglect of the 2004 police reform Plan Siglo XXI, which was much less visible than military patrols (Pontón Reference Pontón2007, 50). In Guatemala, recent efforts to reform the National Police have failed, in part due to lack of government funding toward the police given military priorities (Glebbeek Reference Glebbeek and Uildriks2009).

Legal Incompatibility

As table 1 shows, the constabularization of the armed forces has circumvented the prevailing legal order in most countries. In the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and El Salvador, militaries have conducted domestic law enforcement tasks either against legal restriction seeking to prevent this practice or without laws regulating it. In the Dominican Republic and El Salvador militaries’ semi-permanent involvement in domestic security contravenes constitutional restrictions requiring declared states of exception. In Mexico, the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional in 2018 the Interior Security Bill that sought to formalize the use of the military in public security.

Table 1 also shows several countries in which governments circumvented the legal order for years until legislation was modified. In Brazil (2004), Ecuador (2014), Nicaragua (2015), Peru (2010), Paraguay (2013), and Venezuela (2011), governments either modified the constitution or secondary legislation to legalize the intervention of the armed forces in domestic security. The legal disconnect brought about by constabularization has undermined the rule of law precisely by the same agency who was tasked with upholding it.

Evidence from Mexico

Whereas the previous section presented a region-wide evaluation, this section relies on sub-national evidence from Mexico to further assess the theoretical expectations. Mexico is useful to illustrate the consequences of militarization because of its generalized constabularization of the military since 2006, coexistence of myriad police forces that vary in their degree of militarization and span the spectrum found within Latin America, and fairly typical levels of violence for Latin America. Additionally, we can leverage a joint operation (Culiacán-Navolato) between the military and the federal police in Sinaloa state that began in 2008—for which we have information on confrontations and number of participating personnel (police and military)—to put our hypotheses to test.

First, regarding violence, systematic studies by Flores-Macías (Reference Flores-Macías2018), Merino (Reference Merino2011), and Osorio (Reference Osorio2015) suggest that Mexico’s constabularization has resulted in greater violence compared to the police. As Lessing (Reference Lessing2013, Reference Lessing2017) has shown, this policy has encouraged organized crime to respond in kind, including the formation of squadrons of hitmen with military-grade weapons, equipment, and tactics, especially in contexts of generalized corruption and impunity. This does not mean that violence would have remained at pre-constabularization levels in the absence of constabularization, since there are many causes behind the increase (Yashar Reference Yashar2018). Rather, as Flores-Macías (Reference Flores-Macías2018) shows using a synthetic control method to address endogeneity, the increase would have been less steep—a 17-point difference in the homicide rate, on average.

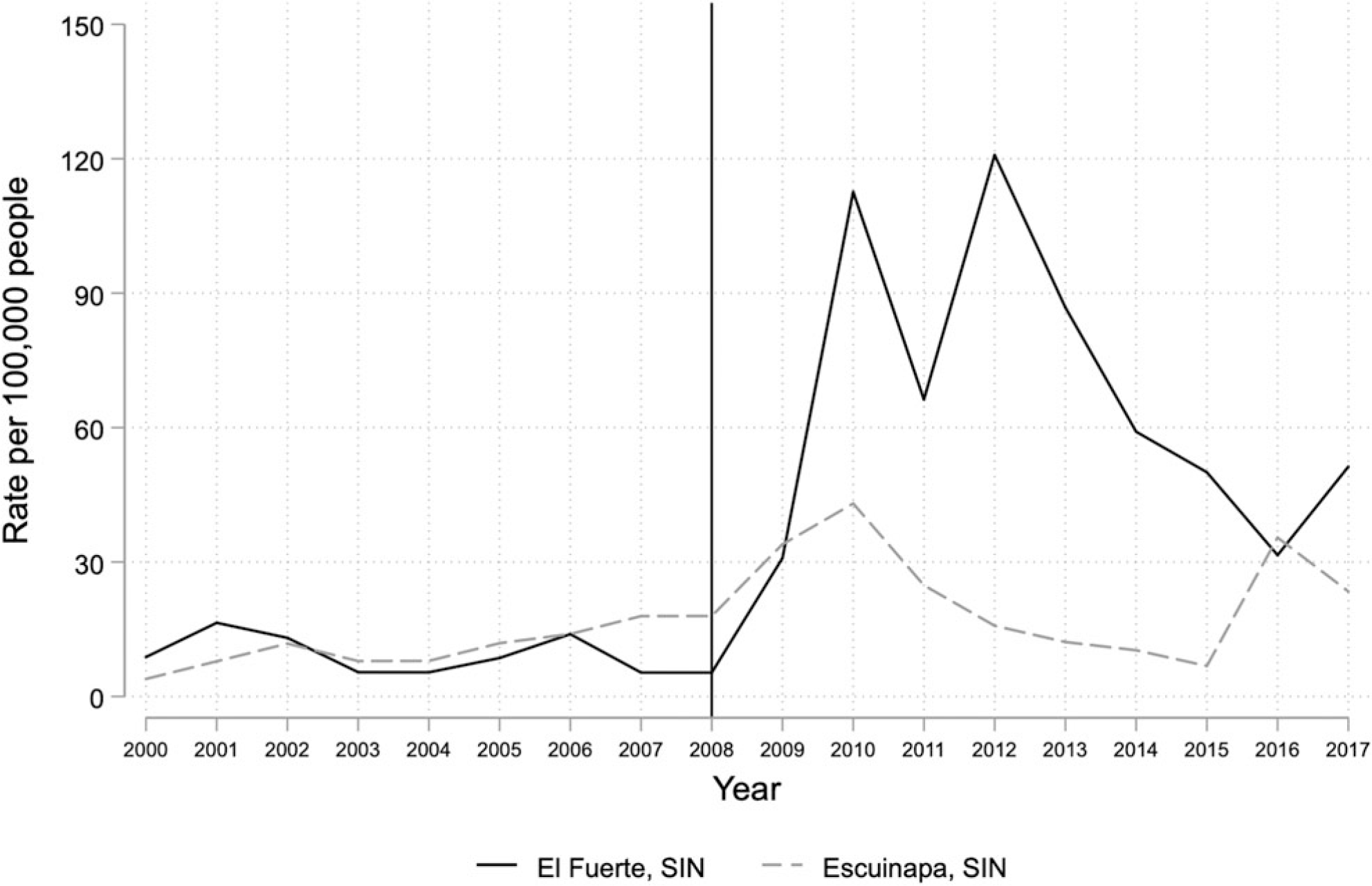

We contribute additional evidence to these authors’ findings by leveraging subnational evidence from a joint operation between the military and the federal police in Sinaloa state for which we obtained data through a series of freedom of information requests. To isolate the effect of militarization and account for the difficulty of the mission and context, we compare two municipalities that closely match in their homicide rates, socioeconomic characteristics, and presence of organized crime until the joint operation began in 2008. Footnote 13 Though both municipalities experienced increases in violence after 2008, as seen in figure 4, our controlled comparison suggests that the homicide rate per 100,000 people increased more in the municipality (El Fuerte) that was treated with military presence.

Figure 4 Homicide rate in comparable municipalities with and without military presence

Note: The vertical black line indicates the start of the Culiacán-Navolato operation.

Providing additional evidence for militarization’s greater disruptive capacity, Pérez Correa, Silva, and Gutiérrez (Reference Pérez2015) show that, during encounters with suspected criminals in 2014, the ratio of civilians killed per soldier killed was fifty-three for the army and seventy-four for marines, compared to seventeen for federal police. That the armed forces’ ratios are considerably higher than the ten to fifteen range suggests excessive use of violence (Chevigny Reference Chevigny and Huggins1991). Regarding the killed-to-wounded ratio, between 2007 and 2014 that of the federal police was 4.8 and the military’s was 7.9. Moreover, according to the National Survey of Population Deprived of Liberty, 74% of people detained by soldiers reported suffering some form of physical violence, almost 15 percentage points more than those detained by other civilian security forces (Ortega Reference Ortega2018).

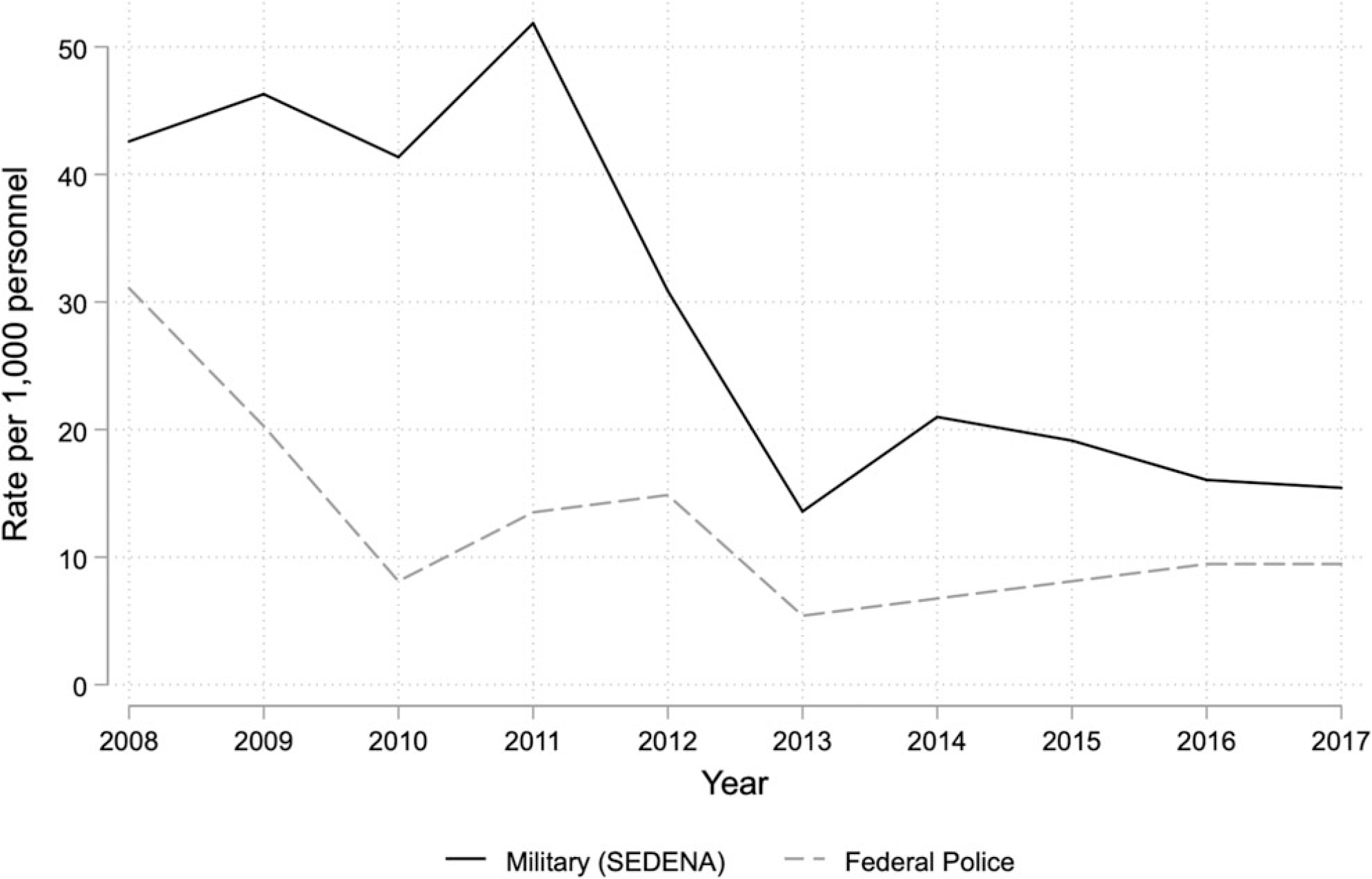

Second, regarding human rights, evidence from Mexico suggests that constabularized soldiers engage in more violations than police. According to Amnesty International (2016), the Mexican military routinely resort to torture, sexual violence, and other violations. Between 2007 and 2016, more than 13,100 cases of abuse against the armed forces were filed with the National Human Rights Commission (refer to the online appendix for details), more than twice the 5,423 filed against the federal police. A similar pattern holds if we look at rates: the rate of complaints against the military grew significantly once soldiers were deployed for public safety purposes—reaching forty-one complaints per 1,000 soldiers in 2011 compared to twenty-one for federal police.

To further test our hypothesis, we again leverage the joint operation between the military and the federal police in Sinaloa. The joint participation in the same operation helps address the concern that soldiers may typically be assigned to more difficult missions than police. Since the federal police does not provide information on officer deployment at the local level, we rely on data made available through press releases on the number of personnel participating in the joint operations that began in 2008. As shown in figure 5, on average, over twice as many complaints of human-rights abuses per 1,000 personnel were filed against soldiers compared to the federal police, even though both were deployed jointly.

Figure 5 Rate of human rights complaints by security force in Sinaloa

Beyond differences in abuses between soldiers and federal police, we also leverage Mexico’s federal system to compare abuse rates between other types of militarized security forces, namely the less militarized municipal police and the more militarized state police. While ideally one would have information on deployment and abuses for all state and municipal police forces in the country, we obtained data for two low-violence states Aguascalientes and Yucatán—and two high-violence states—Nuevo León and Coahuila. Examining both violent and non-violent contexts helps account for differences in difficulty of missions. Footnote 14

Overall, we find that the more-militarized state police generate more abuse complaints than less-militarized municipal police, regardless of whether they operate in high or low violence contexts. Between 2010 and 2016, state police generated 3.2 more complaints per 1,000 police officers in Nuevo León and 2.7 more in Coahuila than their corresponding municipal police. Footnote 15 Similarly, state police in Yucatán and Aguascalientes generated 1.7 more complaints than their municipal police.

Third, several attempts at reforming the federal police have failed since the constabularization of the military in 2006, in part because of the popularity and political expediency of constabularization compared to the difficulty, financial cost, and slow pace of professionalizing the police. Although the government has made some progress toward improving quality among police, constabularization has taken away the urgency of reform. Deadlines to adopt police certification systems have been postponed multiple times. Rather than deepening control mechanisms to address corruption and increase transparency and providing the necessary resources to professionalize the police, the federal government has relied on administrative reorganization, such as trying to unify police under a single chain of command (mando único) (Moloeznik and Suárez Reference Moloeznik and Eugenia Suárez2012) or dismantling the Ministry of Public Safety and folding its federal police under the Ministry of the Interior (Meyer Reference Meyer2014, 20).

The rollout of the National Gendarmerie in 2014 is a case in point. President Peña Nieto originally envisioned this force as complementing the federal police by adding between 40,000 and 50,000 paramilitary personnel and relieving the armed forces. Instead, due to the difficulty in recruiting and training police, the military remained on the streets and a small force of 5,000 members was incorporated into the existing federal police as its seventh division rather than the stand-alone gendarmerie that was planned (Meyer Reference Meyer2014, 20).

Further, while public safety expenditures have grown considerably over the last decade, governments have faced strong incentives to channel resources toward the constabularized armed forces. Between 2005 and 2019, governments increased the armed forces’ budget by MX$69.6 billion—three times the increase assigned to the federal police. Moreover, although as a candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador promised to return the military to the barracks, once in office he expanded the army’s budget by 15 percentage points and cut that of the federal police by 5.5 percentage points. Footnote 16 In the end, the appeal of militarized solutions was such that a new paramilitary National Guard—two-thirds of whom will be soldiers—will entirely replace the federal police by January 2021.

Fourth, Mexico’s armed forces regularly conducted domestic law enforcement operations outside of the prevailing legal order and in clear violation of the Constitution, as confirmed by the Supreme Court’s 2018 decision to overturn the Interior Security Bill aimed at regulating the use of the military for law enforcement purposes. This de facto state of emergency undermined legal certainty for both the armed forces and victims of abuses by the military.

The difficulty of prosecuting members of the armed forces has contributed to impunity and the lack of reparation toward victims. The 2011 murder of 29-year-old Jorge Otilio by the military in Monterrey is illustrative. On his way to work, soldiers opened fire on his vehicle and wounded him. As he stepped out of his vehicle, soldiers fired six additional bullets to his head point blank. Unaware that security cameras were recording them, the soldiers misrepresented the facts in their report and tried to incriminate him by planting a weapon. When Otilio’s family brought the case before a civilian court, the judge referred the case to a military tribunal instead. However, the tribunal claimed it had no jurisdiction because the soldiers were performing police duties. The case bounced back and forth between civilian and military jurisdictions for years because of the lack of legal clarity (Rea Reference Rea2013). Footnote 17

As Amnesty International has highlighted, this legal uncertainty has contributed to the generalized impunity the armed forces have enjoyed during domestic policing operations: “Despite the extraordinarily high number of complaints of sexual violence against women committed by the armed forces, the Army informed Amnesty International in writing that not one soldier had been suspended from service for rape or sexual violence from 2010 to 2015” (2016). This is due to the military conducting parallel investigations that interfere with those of civilian prosecutors and because of the difficulty in getting soldiers to appear before civilian courts (Suárez-Enríquez 2017). Whereas the police also enjoy high levels of impunity in Mexico, the greater violence with which the armed forces operate make the consequences of impunity greater.

Conclusion

This research made several contributions to our understanding of militarization as Latin America’s new law enforcement reality: we unpacked the concept and types of militarized law enforcement; developed theoretical expectations about its consequences for citizen security, police reform, the legal order, and the quality of democracy more generally; and evaluated them with evidence from Latin America and Mexico in particular. It showed that the separation between militaries and public safety that gained traction with the end of military dictatorships is being reversed. Because of rising crime, perceptions of military competence, and U.S. incentives, a majority of countries have engaged in the constabularization of the military, and nine have done so in a generalized fashion across the national territory—including countries with relatively low levels of violence, such as Ecuador and Nicaragua. Further, although the lack of systematic data makes cross-national comparisons challenging and the potential for endogeneity should be taken seriously, the findings suggest that increases in violence and human rights violations, unfinished police reform, and disconnect between the military’s domestic operations and the legal order have tended to follow constabularization. Although further cross-national and country-specific research is required to improve our understanding of militarization’s consequences in Latin America, by conceptualizing its different types, taking stock of its prevalence, and systematically generating and beginning to evaluate theoretical expectations, this article constitutes an important first step toward this end.

The prevalence of these outcomes in countries with constabularized militaries has important implications for Latin American democracies. High levels of violence undermine support for democracy (Arias and Goldstein Reference Arias, Goldstein, Arias and Goldstein2010, 2). They contribute to the notion that authoritarian forms of government might be preferable to address the country’s problems. Across the region, 33% of respondents consider that addressing rampant violence justifies a military coup, a worrisome share considering the region’s low support for democracy and rising support for authoritarianism (Latinobarómetro 2015). In Guatemala, for example, people consider military governments to be more effective at controlling crime than democratic ones (Bateson Reference Bateson2010). Moreover, the sustained reliance on the armed forces can further erode confidence in civilian authorities and re-empower the military, which is ultimately damaging for democracy.

The military’s human rights violations also undermine the quality of democracy, especially when accountability mechanisms are lacking. Whenever militaries operate outside of the legal framework, we can expect abuses to go unpunished. Compared to widespread police impunity typical in the region, not only is the magnitude of abuses greater because of the military’s disruptive capacity, but the sense of impunity resulting from high stakes military operations also strengthens anti-democratic attitudes among the population. Moreover, building effective and trusted police agencies will likely be postponed as long as the armed forces remain involved in law enforcement. The implication of hindering police reform is that constabularization will perpetuate itself as a policy course at the expense of potentially better alternatives.

Constabularization has reversed progress made in civil-military relations regarding the de-militarization of public life since the region’s democratization, which highlighted the importance of separating internal versus external coercion. Although military rule might seem part of a bygone era, reminders of the perils of military intervention are still present today. In Venezuela, the military participated in a failed coup in 2002, and in Honduras the armed forces ousted president Manuel Zelaya in 2009. These examples show how the armed forces continue to pose a threat to democracy in the region (Pion-Berlin and Martínez Reference Pion-Berlin and Martínez2017, 4): democracy is far from consolidated and blurring the line between national defense and public safety opens the door to military rule.

In light of these considerations, and since there is little evidence that involving the military in law enforcement has reduced the levels of drug production, trafficking, or consumption (Kennedy, Reuter, and Riley Reference Kennedy, Reuter and Riley1993; Moreno-Sánchez, Kraybill, and Thompson Reference Moreno-Sánchez, Kraybill and Thompson2003), governments would be well-advised to pay attention to, in addition to comprehensive judicial and police reform, long-term factors–including income inequality, education, and employment opportunities–that have been documented as causes behind the wave of criminal violence in the last two decades (Pérez Reference Pérez2015). Otherwise, moving soldiers out of the barracks and into the streets can further undermine the rule of law and increase levels of impunity—one of the primary reasons why people commit crimes (Kleiman Reference Kleiman1993). This is the paradox of constabularizing the military in the region: while it remains a highly popular policy in Latin America, it appears to be ineffective at best and counterproductive at worst.

The phenomenon of using the military for law enforcement is extending to other parts of the world—especially with the rise of democratically elected populist leaders—which makes the study of how civil-military relations affect democracies all the more pressing. In the Philippines, president Rodrigo Duterte has engaged the military in the country’s anti-drug effort, and the levels of violence have skyrocketed (Moore Reference Moore2017). In Indonesia, President Joko Widodo has directed the armed forces to participate in joint operations with the police (Jakarta Globe 2017). Although conditions are different regarding institutional constraints in these countries, the Latin American experience should inform efforts to militarize law enforcement elsewhere.

Supplementary Materials

-

I. Coding Criteria for the Consequences of Constabularization

-

A. Violence

-

B. Human Rights

-

C. Police Reform

-

D. Legal Order

-

-

II. Supplemental Sources for the Section “Taking Stock of the Militarization of Law Enforcement,” by Country

-

III. Sources for the Section “Evidence from Mexico”

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719003906