Theoretically, the first objectives of the civil rights movement proper could be achieved without Federal action, if the hearts and minds of 200 million Americans were fully attuned to these objectives. But even if everyone wanted to get rid of unemployment and poverty—and practically everyone does—the specific actions toward these ends cannot be formulated, nor fully executed, by 200 million Americans in their separate and individual capacities. This is what our national union and our Federal Government are for, and we must act accordingly.

—A. Philip Randolph, Freedom Budget for All Americans

Within the white majority there exists a substantial group who cherish democratic principles above privilege and who have demonstrated a will to fight side by side with the Negroes against injustice. Another and more substantial group is composed of those having common needs with the Negro and who will benefit equally with him in the achievement of social progress.

—Martin Luther King, Jr. Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?On May 25, 2020, George Floyd, a Black resident of Minneapolis, was arrested by Derek Chauvin, a 44-year-old white police officer, after a local store clerk accused Floyd of attempting to buy cigarettes with a counterfeit $20 bill. While being arrested, Chauvin pinned Floyd to the ground and drove his knee into Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes. Eventually reaching a state of asphyxiation, Floyd laid pulseless for minutes until medical technicians arrived on the scene. Once they arrived, they immediately pronounced Floyd dead.

As news of Floyd’s murder spread across Minneapolis, so, too, did mass demonstrations. Within days, hundreds of thousands of individuals began to take to the street under the banner of “Black Lives Matter,” comprising what the New York Times described as potentially the largest mass movement in American history (Buchanan, Bui, and Patel Reference Buchanan, Bui and Patel2020). Moreover, as protests spread across the country, the interracial bent of the movement soon became apparent. Many political observers began to draw connections to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and whites’ participation in those demonstrations.Footnote 1 Though whites during that era had, early on, expressed many reservations about the latest iteration of the Black Freedom Struggle and the state agitation that came along with it, white public opinion—particularly in the North—began to evolve.Footnote 2 By the mid-1960s, many whites had come to support full civic incorporation of Black people. Indeed, many whites even organized alongside Black people for the expansion of legal and civic rights. However, by the 1960s, white support for the movement had atrophied, scholars evinced a principle-policy gap, or the disconnect between individuals’ political attitudes and their political behaviors (Feldman and Huddy Reference Feldman and Huddy2005; Jackman Reference Jackman1996; Kinder and Mendelberg Reference Kinder, Mendelberg, Sears, Sidanius and Bobo2000).Footnote 3 Consequently, many began to ask the same question that King had asked in 1967, which is “why is equality so assiduously avoided (by whites)?” (King, King and Harding Reference King, King and Harding2010, 4).

But might this time be different? Might the principle-policy gap close? Should we expect whites’ antiracist behaviors to now move in lockstep with their change in antiracist attitudes? With these questions in mind, I seek to provide a theoretical framework that can answer the question under what conditions do whites engage in antiracist behavior? By “antiracist,” I mean political support for the rights of Black people—social, political, economic, or otherwise—ranging from the symbolic to the substantive within the prevailing political order. Racism and capitalism are inextricable, so it is also impossible to analyze antiracism without engaging capitalism. Thus, in my definition of antiracism, I include the clause within the prevailing political order to signify that political actors, while having some degree of agency, do not operate outside of the political-economic structures they find themselves in. Antiracism, like racism, is historically, politically, and socially contingent.

To that end, to understand white Americans’ current antiracist tendencies, I reflect upon how changes to our political-economic order since the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-twentieth century have shaped their efforts to address structural racial injustices. In doing so, I retrieve the thoughts of two of the foremost civil rights leaders from that era: Martin Luther King, Jr. and A. Philip Randolph—both of whom theorized heavily about the role of whites in antiracist struggle, as well as the political-economic order of capitalism under which racism, and by extension, antiracism, operated. King was adamant that the Black Freedom Struggle could not persist without white support—a point he made forcibly in his seminal text, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? Furthermore, in that text, he underscored that forging interracial solidarity would require whites’ recognition of a shared material plight with Black people. As such, King was attuned to the prevailing political-economic forces that shaped political subjectivity and, more specifically, the terms of antiracist politics.

Additionally, Randolph understood the role of class within the Black Freedom Struggle intimately, having founded the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), the first Black labor organization to receive a charter from the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Since Black people were a “working people,” as Randolph often described them, the acquisition of labor rights was, in his view, a fundamental aspect of the Struggle. Moreover, like King, Randolph subscribed to a universalist view of racial justice. I hasten to add that King and Randolph were by no means naïve in believing that recognition of shared material interests between white and Black people could, in itself, foster the types of coalitional politics that they envisioned. They did, however, believe that it was a necessary component (King, King, and Harding Reference King, King and Harding2010; Randolph, Kersten, and Lucander Reference Randolph, Kersten and Lucander2014).

Taken together, I argue that through a close reading of King’s and Randolph’s written works and speeches—particularly after the passage of the Voting Rights Act—it is clear that both men understood the limitations of white sympathy, particularly among those who identify as liberal and who might now be aptly described as comprising the professional-managerial class (PMC) (Ehrenreich Reference Ehrenreich1989). Specifically, they lamented that a large segment of white America would not engage in antiracist behavior beyond symbolic gestures to exhibit their sympathy. This acknowledgment was an enormous impetus behind King’s visionary, though marginalized, Poor People’s Campaign. This interracial, grassroots campaign prioritized solidarity with the white poor and working-class rather than the moral resolve of white professionals. Furthermore, Randolph’s Freedom Budget for All Americans was a comprehensive document and clarion call to the Federal government to eradicate Black poverty and, by extension, white poverty.

Building upon King and Randolph’s insights that recognition of shared class interests was a precondition for whites’ participation in substantive antiracist politics—a process that Randolph believe relied upon a strong alliance with organized labor—I consider the ways in which changes in the capitalist order since the time of their writing have constrained white individuals’ political behavior or, more precisely, their antiracist behaviors. More specifically, I evaluate white antiracism under neoliberal capitalism. While Keynesian capitalism—or, more fittingly, the New Deal order—operated under the assumption that the government played a role in providing labor (workers) with a safety net to protect from the market’s excesses, neoliberal capitalism holds that the state has no such obligation; instead, individuals can, through the development of their human capital, become their own safety net (Brown Reference Brown2015). Unsurprisingly, political elites, increasingly committed to the ideological thrust of a percolating neoliberal order, have, for the most part, dismissed the radical demands outlined in Randolph’s Freedom Budget for All Americans and Martin Luther King’s Poor People’s Campaign (Le Blanc and Yates Reference Le Blanc and Yates2013). How, then, might the radical demands of the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) fare, given that neoliberal capitalism remains hegemonic?Footnote 4

This paper proceeds as follows. First, I provide a brief survey of existing social science research that theorizes the principle-policy gap. The basis of this literature begins with the assumption that whites’ racial attitudes should be predictive of their political behavior. When it is not, this principle-policy gap is often attributed to psychological or sociological forces. I argue, however, that any account of antiracist behavior is incomplete without an analysis of the political-economic circumstances under which individuals operate. Accordingly, I introduce my theory of white antiracism: The privatization of racial responsibility. My theoretical framework considers the conditions under which white individuals’ beliefs in racial egalitarianism—namely white liberals, given that they are likely to harbor such beliefs (as compared to white conservatives)—are likely to predict antiracist behavior, as well as the form this behavior might take.Footnote 5 Given that much of the principle-policy gap research attempts to explain the persistence of racial inequality, particularly in housing and public education, I orient my analysis accordingly. More specifically, given the relentless commodification of both housing and education over the past half-century—coupled with the winnowing of the welfare state and a general undermining of the public good by political elites—education and housing are now viewed as private goods which must be acquired or developed to survive within the neoliberal capitalist order (Brown Reference Brown2015; Eichner Reference Eichner2020). Nevertheless, antiracist concerns have not fallen off the agenda; instead, individuals who express antiracist ideals have been required to consider forms of antiracism that do not inhibit their ability to attain these private goods. As such, I argue that white individuals who harbor antiracist principles will likely engage in antiracist behavior to the extent that it does not impinge upon the attainment of those forms of capital—monetary, human, social, or otherwise—that they perceive as being necessary for survival.

Upon laying out my framework, I also emphasize three conditions that King and Randolph believed were necessary for a successful antiracist project. First, though both men subscribed to the view that any successful movement had to include white Americans, their primary focus was on mobilizing and incorporating poor and working white Americans. For these were individuals with whom a majority of Black people shared a common plight. Neither man, however, downplayed the difficulty of cultivating such a coalition and the potential barrier of white racial prejudice (King, King, and Harding Reference King, King and Harding2010; Randolph, Kersten, and Lucander Reference Randolph, Kersten and Lucander2014). Nevertheless, neither man endorsed the view that white racism was a primordial force, nor did they believe it was immutable. Instead, it was a condition that only political struggle could overcome.

Second, both men had a keen awareness of how "race relations" were, in many ways, a product of the political-economic order and elite governance. In other words, white racism and antiracism alike were products of the material world and the beliefs that individuals hold about the society in which they find themselves. Thus, they believed it was impossible to engage questions of racism or antiracism without grappling with questions of political economy.

Third, and finally, King and Randolph were clear that only the state had the resources and capacity to address the complex problems wrought by capitalism, inter alia joblessness, poverty, access to quality education and housing, segregation, and so forth.Footnote 6 Thus, any successful movement would require getting individuals to recognize their common plight and then directing their needs and concerns upwards at the federal government.

With the framework of the privatization of racial responsibility laid out, I then consider King and Randolph’s insights within the context of our current political moment. In doing so, I argue that elite-driven changes to the political-economic order have made conditions they laid out—solidaristic, interracial politics rooted in material interests and the implementation of state programs to address structural inequalities—difficult to satisfy. Put differently, my theory, the privatization of responsibility, predicts the types of antiracism that white Americans (or, more specifically, white liberal Americans) might engage in, given that King and Randolph’s recommendations have largely gone unheeded.

I conclude by discussing the importance of interracial, class-based politics while also acknowledging the limitations of white racial sympathy, a predominant form of antiracism. Finally, and most importantly, I contend that any successful movement must attack the ideological core of neoliberal capitalism. At the center of this ideological formulation is the notion that the state has no responsibility for securing economic justice—a core demand of the Black Freedom Struggle, past and current—for poor and working people, both Black and others alike.

Prominent Theories of the Principle-Policy Gap

By 1967, King had grown crestfallen that many whites who had enthusiastically supported the first phase of the Civil Rights Movement—the struggle for civil and legal rights—had begun to evince indifference and even hostility towards the movement. As he explained in Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?:

When Negroes looked for the second phase, the realization of equality, they found that many of their white allies had quietly disappeared. The Negroes of America had taken the President, the press and the pulpit at their word when they spoke in broad terms of freedom and justice. But the absence of brutality and unregenerate evil is not the presence of justice. To stay murder is not the same thing as to obtain brotherhood. The word was broken, and the free-running expectations of the Negro crashed into the stone walls of white resistance. The result was havoc. Negroes felt cheated, especially in the North, while many whites felt that the Negroes had gained so much it was virtually imprudent and greedy to ask for more so soon. (King, King, and Harding Reference King, King and Harding2010, 4)

The “disappearance” of white allies once the Black Freedom Struggle began to make more radical, redistributive demands has been the core of much social science research over the past half-century. Although most whites espouse racially egalitarian ideals and reject racism, most remain steadfast in their opposition to a host of social programs that allege to ameliorate such inequalities or, once again, the principle-policy gap. Three prevailing explanations of the principle-policy gap are symbolic racism (or “racial resentment”), realistic group conflict theory, and self-interest.Footnote 7

Symbolic racism is defined as “a blend of anti-black affect and the kind of traditional moral values embodied in the Protestant Ethic” (Kinder and Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981, 416).Footnote 8 Moreover, “symbolic racism represents a form of resistance to change in the racial status quo based on moral failings that blacks violate such traditional American values as individualism and self-reliance, the work ethic, obedience and discipline” (Kinder and Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981, 416). Scholars assert that this belief should manifest most clearly on questions of government assistance to Black people—assistance that most whites find “unfair.” Critically, those in the symbolic racism (or racial resentment) camp make the case that anti-black animus drives white opposition to such programs rather than some perceived material threat and deem such threats largely irrelevant. Thus, in Kinder and Sears’s estimation, whites’ racial resentment towards Black people was the primary driver of their opposition towards racially egalitarian policies or initiatives, rather than self-interested considerations of one’s material standing within the polity (a contention that I will revisit later).

While symbolic racism locates white opposition to racially egalitarian policies in the often-unconscious prejudices they hold towards Black people, realistic group conflict theory argues that white Americans reject actions or situations wherein their standing as the dominant racial group is threatened (LeVine and Campbell Reference LeVine and Campbell1971). Thus, according to scholars in the realistic group conflict camp, instead of conceiving white self-interest as a reflection of one’s individual economic and material standing, it should be conceptualized at the level of the racial group. Through this group-centric orientation, self-interest becomes a driver of whites’ opposition to racially egalitarian policies (Bobo Reference Bobo1983; Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996; Dixon, Durrheim, and Tredoux Reference Dixon, Durrheim and Tredoux2007).

Finally, though the discussion of self-interest within the symbolic racism-versus-realistic group conflict is mainly centered around the conceptual meaning of self-interest and its measurement, some scholars have argued that this debate largely misses the point. More specifically, Green and Crowden (Reference Green and Cowden1992) suggest that while self-interest might have mixed predictive validity within the context of measuring public opinion or attitudes, its effects are much clearer when assessing actual political behavior. For instance, while the authors find mixed evidence for the role that self-interest plays in shaping white individuals’ attitudes towards busing, self-interest seems to be much more critical in shaping white people’s behaviors regarding the issue. Put another way, self-interest may not shape how white Americans think, but it does shape the way they act (Green and Crowden Reference Green and Cowden1992). Indeed, many researchers have pointed to the fact that when policies are presented in a way that makes individuals feel implicated, self-interest tends to have a greater effect on political behavior (Lau and Heldman Reference Lau and Heldman2009; Tedin Reference Tedin1994; Weeden Reference Weeden2016; Weeden and Kurzban, Reference Weeden and Kurzban2017), consistent with Green and Crowden’s findings on white behavioral opposition to busing.

Despite research that has underscored the importance of economic self-interest in motivating political behavior, its centrality within the study of white political behavior and racial inequality more broadly has still not been embraced and, to some degree, is still considered ancillary to racial resentment (Mansfield and Mutz Reference Mansfield and Mutz2009; Mutz Reference Mutz2018; Sides, Tesler and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2019). Complicating matters further is the difficulty in disentangling the effect of self-interest from political ideology and racial resentment. Given that racial resentment and conservative ideology among white individuals is highly correlated (Feldman and Huddy Reference Feldman and Huddy2005), and conservative whites are also more inclined to reject egalitarian policies altogether, how decisive, then, is self-interest in and of itself? “After all,” as Green and Crowden (Reference Green and Cowden1992) note, “those who engage in antibusing activity are typically unsympathetic to the goals of school desegregation” (492). What, then, do we make of those who harbor antiracist sentiments but might not engage in antiracist behavior?

Though each of the theories I reviewed provide useful insights regarding why white individuals are unlikely to engage in antiracism, I argue that they each take for granted the terms of our current political-economic order of neoliberal capitalism and, thus, are limited in their ability to fully theorize white antiracism. This is particularly true if we consider the persistence of the principle-policy gap within the domains of housing and public education. While it is the case that many white individuals argue that they not only support, but in many cases desire more racially egalitarian communities and schoolhouses (Underhill Reference Underhill2019; Warikoo Reference Warikoo2016), the fact remains that even the most liberal white individuals fail to follow through on their antiracist sentiments. This could well be a case of white individuals simply presenting themselves as good white people (Sullivan Reference Sullivan2014). However, because my analysis is necessarily concerned with the materialist foundation of antiracism, I examine the material (rather than purely psychological) conditions that might help us make sense of white antiracism. To do so requires reviewing the connection between race and capitalism—which produces racial disparities in the process—as well as how individuals perceive housing and public education under the neoliberal capitalist economy and how these perceptions, in turn, inform white Americans’ antiracist proclivities within the context of both.

Considering the Political-Economic Terms of White Antiracism

I make two key assumptions about white antiracism in this paper. The first is that individuals are not and cannot be naturally antiracist. By naturally, I mean that whether individuals will engage in antiracist behavior depends on the particularities of the political and social conditions about which they must make decisions. Here, I take a cue from Fields and Fields (Reference Fields and Fields2012), who argue that racism is not an attitude that individuals simply possess but rather is a behavioral response to the social construction of “race.” Similarly, antiracism is not a trait of individuals but is best understood as a political or social expression that must be evaluated in political and social contexts. The second assumption I make is that the existence of antiracist principles does not necessarily predict antiracist behavior. And even when individuals might engage in antiracist behavior, the type of activity that an individual executes will be heavily conditioned by the material conditions they face. For instance, an individual might support the ideals of an antiracist organization and would like to make a monetary donation to help it achieve its goal; however, if this individual is paid a wage that is at or below subsistence level, then the likelihood of them engaging in this particular antiracist behavior concomitant with their antiracist principles will likely be low. Accordingly, my privatization of racial responsibility predicts the conditions under which we might expect white Americans to engage in antiracist behavior, as well as what kinds, given political-economic context.

Racism, “Race,” Capitalism and the Production of Racial Inequalities

The term “racial inequality” has somewhat of a redundant quality. As many historians and theorists of “race” have argued, if we are to conceive of race not as a force of nature but as a social and political phenomenon, then we must understand its function as an ideological formulation (Doane Reference Doane2017; Fields Reference Fields1990; Fields and Fields, Reference Fields and Fields2012; Nash Reference Nash1962). Of course, the ideological function of racism has been to naturalize the idea that not only are there distinct human races but also that there is a clear political, economic, and social hierarchy to which racial designations should correspond. These orders, however, are necessarily unequal and cut against the supposed ideals of American equality. Racism operates to smooth over this apparent contradiction by ordaining Black individuals as naturally inferior and, thus, deserving of a lower political, social, and economic standing relative to white individuals. In the U.S. context, the ideological charge of white supremacy has, depending upon the time and place, been made either explicitly (through, for instance, racial slavery or the regime of Jim Crow) or implicitly, such as color-blind ideologies (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2017; Gans Reference Gans2012). Taken together, though racism has been a consistent organizing principle throughout American history, racial ideologies have been quite protean—bending, weaving, and morphing in response to what is required to sustain the capitalist, neoliberal racial order (Dawson and Francis Reference Dawson and Francis2016).

Racism and capitalism are inextricable and, thus, are mutually constitutive. As a result, one cannot analyze the persistence of racism and its inequalities without also taking stock of how capitalist development produces, absorbs, and, ultimately, underwrites racial ideologies and the behaviors such ideologies engender. As geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore reminds us, though, capitalism is not static, meaning that an adequate analysis of how racism creates inequalities within capitalism must consider the terms of the order at the time of examination. In other words, “If the order is different,” Gilmore argues, “then so are the causes” (Gilmore Reference Gilmore2007, 20).

But while the terms of the capitalist order will ebb and flow—leading racism to have different causal pathways depending on capitalist development—the overarching function of racism, the legitimation of inequality, particularly between races, is consistent. Thus, for example, though the legal system operates as the stabilizing force of capitalism, both by institutionally inscribing hegemonic understandings of the political and social world and, if necessary, coercive force, “laws change, depending on what, in a social order, counts as stability, and who, in a social order, needs to be controlled” (Gilmore Reference Gilmore2007, 12). With this in mind, I transition to an analysis of how housing and public education operate under our current political-economic order while also considering the ways in which racial ideologies pervade both and, consequently, produce (and reproduce) racial inequalities.

Housing and Racism

The housing question has plagued American politics throughout much of its history. At our current political juncture, however, the question of housing access—or so-called “affordable housing”—is front and center within political discourse. In municipalities across the country, large and small, rural and urban, coastal or heartland, providing decent housing for all individuals irrespective of their ability to pay has evaded even the most seemingly progressive locales. Although one’s racial designation does not necessarily insulate them from the issue of housing deprivation, racism has made it such that Black people are, by and large, more likely to find themselves in such a state relative to white individuals (Taylor Reference Taylor2019).

The origins of current housing racial disparities are primarily due to post-World War II housing policy, wherein homeownership became a lofty ideal pushed by the federal government and a critical macroeconomic policy goal driven by political elites (Madden and Marcuse Reference Madden and Marcuse2016; Stein Reference Stein2019). With American capitalism suffering from both an ideological and foundational crisis in the wake of the Great Depression, the extension of homeownership to Americans, who without federal assistance would not have had the means to own property, served as a way for elites to restore confidence in American capitalism (Forrest and Hirayama Reference Forrest and Hirayama2015). In short, homeownership was a policy initiative aimed at restoring the capitalist order.

Of course, in the process of restoring order vis-à-vis the extension of homeownership to many Americans, elites also fortified the racial order through well-known exclusionary tactics such as redlining and blockbusting (Rothstein Reference Rothstein2017). Still more, even when formal barriers to inclusion were dismantled, real estate firms engaged in what Taylor (Reference Taylor2019) calls "predatory inclusion," or extending homeownership to Black Americans under terms unlikely to provide the benefits afforded to white homeowners (such as the accretion of wealth through an increase in property values). Given these racist affairs, many Black Americans have had to resort to public housing under a political-economic order where federal commitments to public housing have been tepid at best (Smith Reference Smith2012).

Public Education and Racism

Historically, public education and the housing question have been interlocked issues. Researchers have demonstrated that because political elites have long understood schooling as a local matter, its organization has necessarily been provincial (Walsh Reference Walsh2018). But while it is the case that public education issues often operate at the local (or statewide) level, like housing, it is often shaped directly by macroeconomic concerns at the federal level (Labaree Reference Labaree1997, Reference Labaree2008, Reference Labaree2012; Collins Reference Collins2019). As a result, to understand how and why public schools remain a site of contestation of racial inequalities, we must first consider how such inequalities came to be and, second, how the terms of our current order reinscribe these inequalities.

As Labaree explains, though it is often taken for granted that the primary purpose of public school is to equip individuals with the credentials necessary for upward social (and, hence, economic) mobility, this has not always been the case (Labaree Reference Labaree1997, Reference Labaree2008, Reference Labaree2012). For much of American history, schooling has served a social rather than a purely economic function (Labaree Reference Labaree1997, Reference Labaree2008, Reference Labaree2012). That has changed significantly, however, over the past half-century (Bowles and Gintis Reference Bowles and Gintis2012; Labaree Reference Labaree1997, Reference Labaree2008, Reference Labaree2012).

Indeed, explicit racist exclusion—or prohibiting Black children from attending schools alongside white students—has been commonplace throughout American society, as have Black Americans’ efforts to combat it. However, as Labaree suggests, though Black opponents of school segregation initially underscored the psychologically deleterious effects of racial exclusion, beginning around the mid-twentieth century, they pivoted to a more explicitly economic argument—contending that segregation relegated Black children to inferior schools; thus, undermining their capacity for economic mobility (Bowles and Gintis Reference Bowles and Gintis2012; Walsh Reference Walsh2018). In so doing, and however inadvertently, they underscored the economic dimensions of education, which would become the predominant frame of education during the latter half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first (Bowles and Gintis Reference Bowles and Gintis2012; Labaree Reference Labaree2012). Education credentialing, then, has increasingly become a process by which individuals seek to acquire a competitive advantage.

I have briefly traced how racism and capitalism have operated hand in hand to produce racial inequalities in housing and public education that persist despite political efforts to alter that reality. Now that we are aware of how racism and capitalism interact to cause these inequalities, I pivot to considering how capitalism and antiracist sentiments are mutually constitutive. Simply put, if we cannot understand the function of racism without investigating the terms of the capitalist order, then the same must be true for antiracism.

Once again, I operate under the assumption that white individuals are not naturally antiracist (or racist). This means that some white people will engage in antiracist behaviors at certain times, while others may not. The question, once again, becomes under what conditions might white individuals engage in antiracist behavior, particularly within the context of housing and public education. Thus, I argue that we must evaluate how housing and public education operate under today’s neoliberal capitalist order. Though racial inequalities in housing and public education are not new, the mechanisms that produce these inequalities, particularly since King and Randolph wrote about these disparities, have changed. I will now pivot to discussing how housing and public education operate under neoliberal capitalism, reinscribing what Dawson and Francis call the neoliberal racial order (Dawson and Francis Reference Dawson and Francis2016).

Housing under Neoliberal Capitalism

Though housing has long been commodified in the United States, its value-form has changed markedly over the past half-century (Madden and Marcuse Reference Madden and Marcuse2016). As scholars have explained, as corporate profits began to fall in the 1960s—a process that accelerated in the face of an inflation “crisis” that gripped the nation during most of the 1970s—real estate became a means to create new wealth (Madden and Marcuse Reference Madden and Marcuse2016; Stein Reference Stein2019). Meanwhile, elite support for state programs to address persistent inequalities began to wane (Doling and Ronald Reference Doling and Ronald2010; Ronald, Lennartz and Kadi Reference Ronald, Lennartz and Kadi2017). This two-pronged move—the growth of what Stein calls “the real estate state” (Stein Reference Stein2019) and devolution, or the state’s winnowing commitment to social programs (Brown Reference Brown2015)—ultimately turned housing or, more fittingly, homeownership into a form of “asset-based welfare” (Donald and Ronald Reference Doling and Ronald2010). As Doling and Ronald (Reference Doling and Ronald2010) explain, “The principle underlying an asset-based approach to welfare is that, rather than relying on state-managed social transfers to counter the risks of poverty, individuals accept greater responsibility for their own welfare needs by investing in financial products and property assets which augment in value over time” (165). “Housing in national welfare systems,” they continue, “the position of housing in national welfare systems, then, is much more complex than its role simply as providing physical shelter” (166). Housing, under neoliberal capitalism, has become what Madden and Marcuse (Reference Madden and Marcuse2016) describe as a hyper-commodity.

With housing doubling as a form of asset-based welfare, individuals and their families with the means to do so purchase homes with the expectation that it will not only provide a place for them to live, but will also serve as an asset whose monetary value will grow appreciably—providing material security in the process. Of course, whether individuals have access to this commodity will depend heavily upon their class position and racial status. Consequently, homeownership might be reasonably interpreted as a form of asset-based welfare that is heavily class-skewed (towards middle-income families and above) and racialized, with Black Americans being less likely than white Americans, on average, to enjoy the economic benefits of homeownership. This fact means that in the absence of federal social programs to provide adequate housing for those unable to become homeowners—a disproportionate number of Black—the inequalities produced by the intersection of racism and capitalism will likely continue unabated.

Public Education under Neoliberal Capitalism

I have thus far explained how racial ideologies have historically operated within the realm of public education, underwriting evident racial inequalities that persist to this day. And, as I have argued, these inequalities persist despite antiracist efforts to the contrary. So why is it that racial disparities persist even when individuals, particularly white liberals, profess racially egalitarian ideals and subscribe to the view that Black and white children should have access to good schools?

In considering this question, I again argue that we must consider how the terms of the neoliberal capitalist order inform individuals’ understanding of schooling and, consequently, how they interact with it. Like housing, education is viewed by large swaths of the population as a commodity that must be acquired in the face of an order where many individuals fear downward mobility, especially given a weak social safety net (Eichner Reference Eichner2020). As Labaree (Reference Labaree2012) explains, “gone is the notion that schools exist to promote civic virtue for the preservation of republican community; in its place is the notion that schools exist to give all consumers access to a valuable form of educational property” (40). Referring to this process as “educational consumerism,” Labaree goes on to describe this arrangement as “the sum of the choices about education that individual patterns and children make, based on the social and economic benefits that they will gain personally by attaining higher levels of schooling and acquiring the associated credentials” (81).

Given these political-economic conditions, it is clear that many white individuals are in somewhat of a conundrum. Making education and housing more equitable would likely mean eschewing decisions based upon their expected payoff in the market. And since markets are, by their very nature, unequal, and because both the arenas of housing and public education have been shaped by racism, a commitment to the order as it stands will necessarily mean the perpetuation of the racial status quo. However, as Eichner (Reference Eichner2020) explains, families often cannot dictate the terms of the political order. Consequently, their decisions are in many ways circumscribed by market forces. In sum, families may be “free to choose,” as Milton Friedman (Friedman and Friedman 1980) intoned while pitching the political-economic benefits of a market economy, but as Adam Kotsko (Reference Kotsko2018) warns, choosing wrong can mean real material costs. How, then, might white individuals who harbor antiracist principles engage in antiracist behavior? I now turn to my theory, the privatization of racial responsibility, to make that assessment.

The Privatization of Racial Responsibility: A Theoretical Framework for Contemporary White Antiracism

The privatization of racial responsibility illuminates the notion that white individuals, particularly those who identify as liberal and comprise the PMC, are likely to make antiracist commitments that are symbolic rather than material in nature. This, I argue, is a result of the material cost structure associated with the terms of the neoliberal capitalist order. To be sure, some scholars have argued that antiracism has not been affected by neoliberal capitalism but is a product of it (Reed Reference Reed2017; Reed Reference Reed2018).Footnote 9 Indeed, while it may be the case that antiracism has taken on a largely symbolic form over the past half-century, I argue that such expressions of antiracism must be explained, rather than subject to speculation. To wit, while it may be the case that many white individuals in the PMC are often inclined to more symbolic or expressive forms of antiracism, this behavior must be explained by considering the terms of the political-economic order under which individuals operate. As I have argued, white liberals’ antiracism commitments are often juxtaposed with their material considerations, such as creating the “best” future for their children. For, as Kinder and Sanders (Reference Kinder and Sanders1996) remind us, “it is the family, not the community and certainly not politics, that occupies the energy and attention of most Americans” (51). Seen through this lens, we should expect that white liberal PMC’s racial commitments will be highly symbolic because they do not perceive these symbols as antithetical to their family’s material or social position or, more concisely, their familial capital.

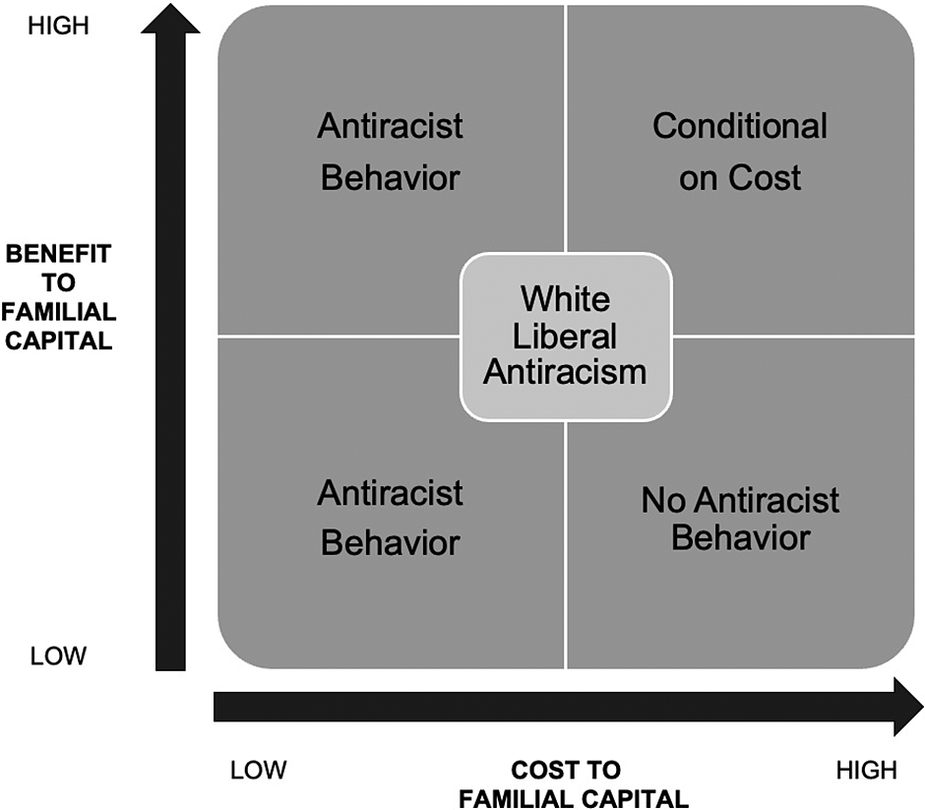

Thus, white liberals’ commitments to racial justice depend upon the degree to which they believe an initiative or policy will threaten their familial capital. This formulation requires us to know the costliness of an act relative to one’s familial capital.Footnote 10 Figure 1 provides a rough assessment of how white PMCs might perform antiracism under neoliberal capitalism. As the matrix suggests, there is one obvious circumstance under which we might expect liberals to support an act of racial justice: when it is relatively low-cost to one’s familial capital. Here, we might imagine a white liberal family electing to place a “Black Lives Matter” sign on their front lawn, tweeting positively about the Movement for Black Lives, or even making a small donation to a local civil rights organization. All reflect a principled act but do not at all implicate one’s familial capital. So while these might be principled acts, they do not get at the core of durable racial inequalities. For as King reminds us, these types of gestures are limited in bringing on the kinds of politics necessary to alter the structure of our political-economic order.

Figure 1 Relationship between white liberals’ familial capital and their antiracist behavior

The top-left quadrant reflects situations in which a white liberal family might support a political act that will provide a clear material benefit but at little to no cost. An example of this might be voting for a progressive candidate who includes addressing racial inequality as one of their campaign commitments and other social issues that are politically important to the family (such as increasing school funding, for instance). Under such a scenario, they can satisfy their own material needs and their principled commitments to racial justice without necessarily having to shoulder any material costs directly. In other words, these are circumstances under which Black people might be inadvertent beneficiaries of an act or policy, even if they are not the foremost consideration. Warikoo (Reference Warikoo2016) also explains that many white individuals support diversity initiatives, particularly within higher education, because they believe it will allow them to relate better with different “racial groups,” making them more appealing on the job market. In such cases, white individuals view “diversity” as beneficial (so long as it does not come at their expense). Under each scenario, durable racial inequalities might be ameliorated, though the extent to which racial gaps might be closed is questionable.

When white liberals perceive an act of antiracism as being costly to their familial capital while rendering few or no material benefits, we should expect the initiative to be met with opposition. The battle over residential zoning laws encapsulates this phenomenon. Many white liberal enclaves are often antagonistic towards changing zoning laws in a way that might lead to greater neighborhood density (Geismer Reference Geismer2017; Trounstine Reference Trounstine2018). On the one hand, this maneuver tends to preserve individuals’ social status (and thus, familial capital) but, on the other hand, perpetuates racial inequality. Therefore, while supporting greater density might be moral, embracing such an initiative is often perceived as requiring an undue degree of material sacrifice. This situation leaves racial inequality firmly entrenched.

When white liberals view an initiative as both costly and beneficial, they will engage in antiracist behavior conditional on the act’s perceived cost. For example, let us imagine that a local school district proposes a $200 million bond issue to pay for technology and infrastructure improvements. Passage of the bond will mean an increase in property tax, with higher-earning families expected to shoulder a higher cost burden. Although white liberal families with children in local public schools stand to benefit from the bond’s passage, they may not feel the effort is worth the increase in property taxes. Thus, under this scenario, they might opt for the status quo—in this case, a rejection of the bond issue. If, on the other hand, they believe that the proposed benefits of the bond vis-à-vis an improvement to their child(ren)’s education (and, by extension, their familial capital), then they might very well be inclined to support it.

In sum, we might then derive a handful of propositions regarding when white liberals might engage in antiracist behavior under the neoliberal political-economic order:

-

• If an antiracist initiative comes at a small or no cost to one’s familial capital, then they will engage in antiracist behavior.

-

• If an antiracist initiative comes at a high cost while offering no benefit to one’s human familial capital, then they will not engage in antiracist behavior.

-

• If an antiracist act initiative at a high cost but also offers a high degree of benefits to one’s familial capital, then they will engage in antiracist behavior if the cost does not outweigh the benefit.

-

• If an antiracist initiative provides benefits to one’s familial capital, and is low cost, then they will engage in antiracist behavior.

To reiterate, each of the following propositions operates under the assumption that individuals are operating under the political-economic conditions of neoliberal capitalism. In other words, if these conditions were to change, then this theoretical account should be revaluated. As it stands, however, I argue that white liberal antiracism will take the form of white sympathy given these current circumstances. In the following section, I reflect upon what this might mean at our present political juncture.

King and Randolph on The Political Limitations of White Sympathy

Both King and Randolph understood the political limitations of racial sympathy.Footnote 11 While many whites are often sympathetic to Black Americans’ calls for racial equality, this sympathy does not translate to supporting radical political projects that would significantly improve the plight of poor and working people. One reason for this is because political solidarity and political allyship are not coterminous. As King wrote in Community, “A true alliance is based upon some self-interest of each component group and a common interest into which they merge.” Thus, while King (Reference King, King and Harding2010) understood and was willing to concede that “within the white majority there exists a substantial group who cherish democratic principles above privilege and who have demonstrated a will to fight side by side with the Negroes against injustice” (allyship), he also knew that “another and more substantial group is composed of those having common needs with the Negro and who will benefit equally with him in the achievement of social progress” (solidarity) (52-53). In other words, the types of antiracist behavior that whites will engage in are a function of both their beliefs about racial equality in principle and their class position. King and Randolph both understood, then, that if whites were to engage in antiracist behavior, it would likely be a function of not only their moral views about Black people but of their material interests by nature of their class interests.

Let us take seriously King’s formulation that some white people will occupy the role of ally, while others might find themselves in solidarity with Black people due to common material interests. Antiracism makes room for both manifestations. Allowing for variation in antiracist behavior will enable us to typify different expressions of antiracism across both time and space.

Accordingly, I argue that any analysis of antiracism should include, within it, a class analysis. In applying this framework to the study of white antiracism, I consider the behaviors of both working-class whites and those who comprise the PMC. I argue that, under neoliberal capitalism, whites PMCs are more likely to engage in antiracism than are working-class white individuals. Given the purported “Great Awokening” of white Americans over the past five years (Yglesias Reference Yglesias2019)—and in the wake of Floyd’s police-murder, in particular—such a dynamic may seem obvious. Still, I want to argue that such politics is a break from historical precedent. I contend that, due in large part to their class position, white PMCs tend to engage in the kinds of antiracist politics that accord with (or at least does not come in conflict with) their class interests. Thus, white PMCs’ antiracism manifests chiefly as symbolic commitments to racial justice.

King, specifically, was aware of the limits of sympathy rather than solidarity. Indeed, King observed that:

A true alliance is based upon some self-interest of each component group and a common interest into which they merge. For an alliance to have permanence and loyal commitment from various elements, each of them must have a goal from which it benefits and none must have an outlook in basic conflict with the others. (King, King, and Harding Reference King, King and Harding2010, 159)

Though he was by no means dismissive of whites who evinced genuine sympathy towards the efforts of Black people to secure freedom, he knew that doing politics required identifying similarities in material conditions which would serve as the foundation of interracial solidarity. To this end, King saw a natural alliance between those engaged in the labor struggle and those fighting for Black freedom. To wit, King intoned that:

The two most dynamic movements that reshaped the nation during the past three decades are the labor and civil rights movements. Our combined strength is potentially enormous. We have not used a fraction of it for our own good or for the needs of society as a whole. If we make the war on poverty a total war; if we seek higher standards for all workers an enriched life, we have the ability to accomplish it, and our nation has the ability to provide it. If our two movements unite their social pioneering initiative, thirty years from now people will look back on this day and honor those who had the vision to see the full possibilities of modern society and the courage to fight for their realization. (King and Honey Reference King and Honey2012, 120)

Similarly, Randolph expressed reservations about building a movement based upon the sympathetic attitudes of whites who did not necessarily feel compelled to engage in the types of political struggles that Randolph believed were part and parcel of any legitimate efforts to achieve Black Freedom. Randolph, even more so than King, was adamant that labor struggles needed to be driven by those who were, in fact, most implicated by the degrading forces of the capitalist order. Hence, he argued that:

It is well-nigh axiomatic that while white and Negro citizens may sympathize with the cause of striking miners or auto-workers or lumber-jacks, the fact remains that the miners, auto-workers and lumber-jacks must take the initiative and take responsibility and take risks themselves to win higher wages and shorter hours. By the same token, white liberals and labor may sympathize with the Negro’s fight against Jim Crow, but they are not going to lead the fight. They never have, and they never will. (Logan Reference Logan2001, 133)

Taken together, both men were unequivocal in their views that white antiracism should be predicated upon material solidarity—rather than racial sympathy—and organized around labor rights. This view, of course, meant bringing white workers into the fold. Thus, it is to the white working class that I will now turn.

The White Working Class and the Weakening Foundations of Solidarity

It has become commonplace to treat working white people as irredeemably racist—captured by the racist ideologies that the Republican Party, in particular (though by no means exclusively) has relied upon to build electoral coalitions in the “post-Civil Rights Era” (Haney-Lopez Reference Haney-López2014; Mason Reference Mason2018; Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2019). But neither King nor Randolph believed that racial prejudice was a congenital or otherwise inherent trait of individuals. On the contrary, both men acknowledged that racism was, without question, a powerful force in shaping American politics, without submitting to the view that it was a permanent, indestructible construct. To wit, King noted that:

Racism is a tenacious evil, but it is not immutable. Millions of underprivileged whites are in the process of considering the contradiction between segregation and economic progress. White supremacy can feed their egos but not their stomachs. They will not go hungry or forego affluent society to remain racially ascendent. (King, King, and Harding Reference King, King and Harding2010, 161, emphasis added)

Randolph’s views on the racism of the white working-class mirrored King’s. He argued that it was necessary to remember that race prejudice was a learned behavior rather than a metaphysical phenomenon (Randolph, Kersten, and Lucander Reference Randolph, Kersten and Lucander2014). Thus, successfully combatting race prejudice meant successfully changing the material circumstances in which individuals found themselves.Footnote 12

This latter point is critical, for it implies that the only way to reduce race prejudice is to alter the conditions that exacerbate the perpetuation of race prejudice. In other words, the causal pathway is such that material conditions change human practices, which shapes attitudes, not the other way around. As King explained:

It doesn’t mean that we will change the hearts of people, but we will change the laws and habits of people, and once their habits are changed pretty soon people will adjust to them just as in the South they’ve adjusted to integrated public accommodations. I think in the North and all over the country people will adjust to living next door to a Negro once they know that it has to be done, once realtors stop all of the block busting and panic peddling and all of that. When the law makes it clear and it’s vigorously enforced we will see that people will not adjust but they will finally come to the point that even their attitudes are changed. (King and Washington Reference King and Washington1991, 389)

We can observe King’s view that changing hearts and minds should not be the aim of antiracist politics. Instead, those committed to emancipatory politics should be focused on changing the structures that shape human behavior, which can, in turn, lead people to update their attitudes.

To that end, it is impossible to understand the racial attitudes of the white working class without an account of the structural changes to our political-economic order since the late 1960s. Though racism was undoubtedly at play, so, too, was political-economic restructuring. As I have already mentioned, one of the critical characteristics of neoliberal capitalism has been the growing prevalence of non-union jobs. Unsurprisingly, then, a central feature of neoliberal capitalism has been declining union membership across the board, but especially within the white working class. Figure 2 calls attention to this fact. Here, we can observe the declining union membership of white workers during the neoliberal era. This finding has important implications for antiracist politics. As political scientists Paul Frymer and Jake Grumbach (Reference Frymer and Grumbach2021) show, union membership moderates white prejudice, heightens class consciousness, and, by extension, prospects for interracial solidarity.Footnote 13 In the absence of unions or similar institutions that can articulate a class program around which white workers can coalesce, they are likely to be drawn to racist appeals, particularly those made by Republican elites. These data comport quite well with King’s observation that we must address structural conditions to change people’s political attitudes. They also lend credence to King and Randolph’s contention that any successful antiracism program must engage with labor and its potential to organize the white working class.

Figure 2 White working class union membership 1968–2016

Note: I identify the “white working class” as those white respondents who, on the ANES, identified their social class as either average working, working, or upper working class.

Source: American National Election Survey (ANES).

Conclusion

As Randolph explained in the Freedom Budget, addressing economic oppression was a task too large for individuals, despite whatever good intentions they might have (Randolph Reference Randolph1966).Footnote 14 In addition, Randolph understood that the federal government had both a cultural and ideological function, noting that “its policies and programs exert the most powerful single influence upon economic performance and social thinking” (Randolph Reference Randolph1966, 2).

However, at our current political juncture, the conditions required for successful antiracist politics, as articulated by King and Randolph, are not being met. In an era of neoliberal capitalism, Black-white alliances are not necessarily predicated upon similar material needs. Additionally, state efforts to secure economic justice for poor and working people are weak. Elites of both parties often frame demands to expand the social welfare state as pollyannaish, fortifying the common-sense interpretation of the United States as a zero-sum society. Consequently, those who allege to be antiracists—namely white individuals—are expected to “give up” their privilege, lest they be deemed hypocritical. All of this is transpiring while many, particularly in the PMC, have a (real or imagined) “fear of falling,” as Ehrenreich (Reference Ehrenreich1989) once noted. What are the terms of antiracism under these political conditions? It means that current white antiracism, then, is markedly different than during the time of King and Randolph’s writings and must be analyzed in light of these political-economic changes. At our current political moment, Antiracism’s predominant form is racial sympathy rather than political solidarity rooted in similar material interests. And since neoliberal capitalism is necessarily antagonistic towards most working people’s needs—a disproportionate number of whom are Black—its preservation will, as a matter of course, mean that racial inequality will mainly continue unabated. This is the consequence of relying on individuals—rather than the federal government—to rectify a structural issue, racial oppression, as Randolph (Reference Randolph1966) forcefully argued.

Contra to the warnings of Randolph, on July 9, 2020, Betsy Hodges, the former mayor of Minneapolis—the location of George Floyd’s murder—penned an op-ed in the New York Times questioning white liberals’ willingness to make sacrifices on behalf of historically marginalized communities. Hodges (Reference Hodges2020) stated that “white liberals, despite believing we are saying and doing the right things, have resisted the systemic changes our cities have needed for decades.” She also indicted white liberals for “preserving white comfort at the expense of others.” She went on to describe Minneapolis’ politics in zero-sum terms, claiming that white liberals’ preferences for symbolic rather than structural changes to the status quo disadvantage “communities of color” through “the hoarding of advantage by mostly white neighborhoods.” Accordingly, Hodges located the solution to racial inequality in white liberals’ ability to “find ways to make our actions match our beliefs this time around,” rather than settling for symbolic gestures. Thus, in Hodges’s view, the fate of racial equality rests heavily in the hands of the white liberal Americans, an illustration of the privatization of racial responsibility.

There are limitations to such an arrangement. While a growing number of white PMCs may be identifying as liberal and, as a result, aligning themselves with the Democratic Party, the terms of our political-economic order will likely render radical politics unattainable. Given the precarity of even middle-class life, expecting individuals to sacrifice their material assets for principled causes does not seem politically realistic. As Harrison and Bluestone (Reference Harrison and Bluestone1993) state, “few of us will bet our homes, our cars, or our jobs. We are all gamblers to some extent, but we value basic security even more” (175). Simply put, a neoliberal political-economic order that is relentlessly competitive and zero-sum in nature undermines the potentiality of interracial, solidaristic racial politics. As such, any form of progressive politics—antiracist or otherwise—must strike at the core of what Hall and O’Shea (Reference Hall and O’Shea2013) identified as “common-sense neoliberalism” and what Randolph (Reference Randolph1966) described as the “social thinking” of how our society should operate—which is an inherently political question.

Some have questioned whether white liberals are genuinely committed to racial equality or if their leftward turn is simply indicative of "expressive” partisan proclivities (Blow Reference Blow2020; Chudy and Jefferson Reference Chudy and Jefferson2021). But whether their antiracist expressions are genuine or performative is neither here nor there.Footnote 15 White PMC’s class interests are often incompatible with the radical demands of the Black Freedom Struggle and, as a result, can serve as a barrier to more substantive change.Footnote 16 For if an alliance is to have “permanence and loyal commitment from various elements,” as King once reminded us, “each of them must have a goal from which it benefits and none must have an outlook in basic conflict with the others” (King, King, and Harding Reference King, King and Harding2010, 159).

What about the white working class? Given the weakening institutional channels that might help cultivate the types of solidaristic politics that King and Randolph outlined, a growing segment of the white working class seems politically and socially out of reach. Thus, absent radical changes to the neoliberal capitalist order that continues apace, if and when white Americans engage in antiracist behavior in the era of Black Lives Matter, it will likely manifest as expressions of racial sympathy rather than material solidarity—a result of the privatization of racial responsibility—despite King and Randolph’s warnings about the limitations of such politics, particularly as it pertains to the success of the Black Freedom Struggle.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Candis Watts Smith and John Aldrich of Duke University, as well as participants of the Triangle Intellectual History Seminar for their very detailed feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript. He is also grateful for the very generative comments offered by each of the reviewers during the revision process. But above all, the author would like to thank Martin Luther King, Jr. and A. Philip Randolph for fighting tirelessly for Black freedom and justice for working people everywhere.