Every family has an enfant terrible. But as I am a Christian Democrat, I prefer to keep my enfant terrible inside the family and to be able to talk and reason with him.

— Joseph DaulFootnote 1In February 2019, Freedom House downgraded Hungary from Free to Partly Free, referring to “sustained attacks on the country’s democratic institutions by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party, which had used its parliamentary supermajority to impose restrictions on or assert control over the opposition, the media, religious groups, academia, NGOs, the courts, asylum seekers, and the private sector since 2010” (Freedom House 2019). Amonth later the European People’s Party (EPP) suspended the membership of Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Alliance, on the grounds of democratic backsliding. In Poland, Jarosław Kaczyński’s Law and Justice Party (PiS) won a majority of the seats in the October 2015 elections and set out on a similar path. However, unlike Fidesz, the new PiS government did not enjoy a constitution-altering supermajority, and soon clashed with the constitutional court. Four years on, the party retained its majority in the Sejm, but narrowly lost control of the Senate.

Meanwhile in Slovakia, Robert Fico’s Smer – Social Democrats won a majority of the seats in the March 2012 election, but did not go down the same path. Instead, Fico “went out of his way” to demonstrate his commitment to pluralistic democracy (Valášek Reference Valášek2012). Having lost the majority in 2016, Fico quickly struck a deal with the Slovak National Party (SNS) and the ethnic Hungarian Most–Híd (Bridge) party.Footnote 2 The murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée Martina Kušnírová in February 2018 sparked big demonstrations in all major cities, forcing him to resign, but the coalition struggled on. A Financial Times editorial described the victory of the liberal anticorruption activist Zuzana Čaputová in the March 2019 presidential elections as “a ray of hope” and “a cause for celebration in a region where authoritarianism and crony capitalism are sadly becoming the norm” (Financial Times 2019b). Slovakia had been a democratic laggard under Vladimír Mečiar’s leadership (1994–1998), but by 2019 it was among the most democratic post-communist EU member states.Footnote 3

In the Czech Republic, the controversial billionaire and leader of the ANO (“yes”) party Andrej Babiš attracted considerable criticism as prime minister. ANO came first in the October 2017 election, but after failing to win the investiture vote Babiš formed a minority government with the Czech Social Democratic Party that depended on Communist support. Meanwhile the lower house had voted to strip Babiš of his immunity to allow the police to investigate his role in the EU subsidies fraud case associated with the “Stork’s nest”, a subsidiary of his company Agrofert. By 2020 the charges against his family members had been dropped, but the public prosecutor had reopened the subsidy fraud case against Babiš (Politico 2019). Although the prime minister has repeatedly dismissed the charges as a conspiracy, this is a far cry from Fidesz and PiS-style assertions that the judiciary must operate in the interest of the government.

Hungary and Poland are paradigmatic cases of democratic backsliding (Scheppele Reference Scheppele2016, Reference Scheppele2018; Sitter et al. Reference Sitter, Batory, Kostka, Krizsan and Zentai2016; Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2019). However, as the backsliding narrative gained traction, the term has been widely applied to the post-communist region (Cianetti, Dawson, and Hanley Reference Cianetti, Dawson and Hanley2018; Hanley and Vachudova Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018; Pehe Reference Pehe2018; Mesežnikov and Gyárfášová Reference Mesežnikov and Gyárfášová2018; Vachudová Reference Vachudova2019). The early optimism is gone; “the narrative of progress in the region is dead, replaced by democratic backsliding—and even sliding into authoritarianism” (Hanley and Vachudová Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018, 276); “the idea that democracy is backsliding in East-Central Europe is fast becoming the consensus view” (Dawson and Hanley Reference Dawson and Hanley2016, 21).

As Merkel (Reference Merkel2010, 19) pointed out, this optimism was in part based on conceptual stretching. Many scholars applied the democracy label to regimes that were in effect hybrid regimes. We argue that the current “democratic backsliding” narrative is based on a similar kind of conceptual stretching, now erring in the opposite direction. More specifically, some scholars fail to distinguish between backsliding and hollowing out, and between liberal democracy and liberalism.

We set out to rescue the concept as an analytical tool, and then assess to what extent it applies to the four Visegrád states. We define “democratic backsliding” as a process of deliberate, intended action designed to gradually undermine the fundamental rules of the game in an existing democracy, carried out by a democratically elected government, and argue that, by 2020, both PiS and FideszFootnote 4 qualified, whereas no substantial backsliding had (yet) occurred in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. To be sure, corruption scandals, populism, clientelism, polarised political debate, and large-scale demonstrations shook both countries. All four went back on commitments they made when they joined the EU, notably to address discrimination on the grounds of gender and disability (Krizsan and Roggeband Reference Krizsan and Roggeband2018; Grzebalska and Pető Reference Grzebalska and Pető2018). However, when it comes to undermining the fundamental rules of the game in an existing democracy the Czech and Slovak cases remain closer to the Italian “second republic” (ca. 1994–2018) than the radical de-democratization pushed through in Hungary and Poland. The problems in the Czech case—weak parties, low trust in government institutions, fragile coalitions, low party membership (Guasti and Mansfeldová Reference Guasti, Mansfeldová, Guasti and Mansfeldová2018; see also Balík et al. Reference Balík2016, and Vachudová Reference Vachudova2019)—are more a matter of hollowing out than backsliding.

In line with much of the literature on democratization, we focus on agency—and what agents actually achieve. In order to backslide, power-holders need motive, opportunity, and the absence of constraints. We start with a brief review of the literature on democratic backsliding and an operational definition of the concept. The second section maps backsliding in the Visegrád Four, with some comparisons to Mečiar’s Slovakia and Silvio Berlusconi’s Italy. The third section explains variations in backsliding in terms of motive, opportunity, and the strength of opposing or constraining forces. The conclusion assesses the limits to backsliding.

What Is Democratic Backsliding?

The literature on democracy has come full circle since 1989, when Francis Fukuyama predicted “the end of history as such: that is … the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government” (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama1989, 4). The end of communist rule was widely seen as the culmination of Samuel Huntington’s (Reference Huntington1991) third wave of democratisation. Already in 1996 Larry Diamond asked if it was over, while Michael McFaul (Reference McFaul2002) regarded post-communist cases as a fourth wave of transitions, to democracy and dictatorship. The notion of “democratic recession” has been debated (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2015; Merkel Reference Merkel2010), but V-Dem data demonstrate that a wave of autocratization is currently unfolding (Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019).

Much like the over-production of qualifying adjectives to democracy in the 1990s and 2000s (Giebler, Ruth, and Tannenberg Reference Giebler, Ruth and Tanneberg2018), scholars have invented a number of terms to capture its degradation (Daly Reference Daly2019). Democratic backsliding has gained the most traction (Waldner & Lust Reference Waldner and Lust2018; Jee, Lueders, and Myrick Reference Jee, Lueders and Myrick2019), and is most commonly understood as deliberate departure from democracy and the rule of law, or in the words of Nancy Bermeo (Reference Bermeo2016, 6) “the state-led debilitation or elimination of any of the political institutions that sustain an existing democracy” (see also Bugarič & Ginsberg Reference Bugarič and Ginsburg2016; Foa & Mounk Reference Foa and Mounk2017; Levitsky & Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Mechkova et al. Reference Mechkova, Lührmann and Lindberg2017; Pech & Scheppele Reference Pech and Scheppele2017; Sitter & Bakke Reference Sitter, Bakke and Laursen2019). Others have focused on “bad governance” (Carothers Reference Carothers2007, 199), the quality of democracy (Sedelmeier Reference Sedelmeier2014), human rights (Guzman and Linos Reference Guzman and Linos2014), corruption and state capture (Hanley Reference Hanley2014; Ágh Reference Ágh2015), or violations of fundamental EU norms and laws (Müller Reference Müller2015; Sitter et al. Reference Sitter, Batory, Krizsan and Zentai2017).

Our definition of democratic backsliding rests on four key points. First, like Bermeo, we take movement away from democracy as a starting point. Second, like Waldner and Lust (Reference Waldner and Lust2018, 95), we limit this to gradual, incremental change. Sliding denotes smooth and continuous movement, not rapid democratic breakdown. Third, we regard both democratization and democratic backsliding as open-ended processes that may or may not lead to regime change. Where the process ends—if it ends—is an empirical question, not a part of the definition. Fourth, pace Bermeo, backsliding is elite-driven, and involves successful willful acts by elected power-holders to undermine democracy. Consequently, backsliding is about what power-holders do, not what they would like to do.

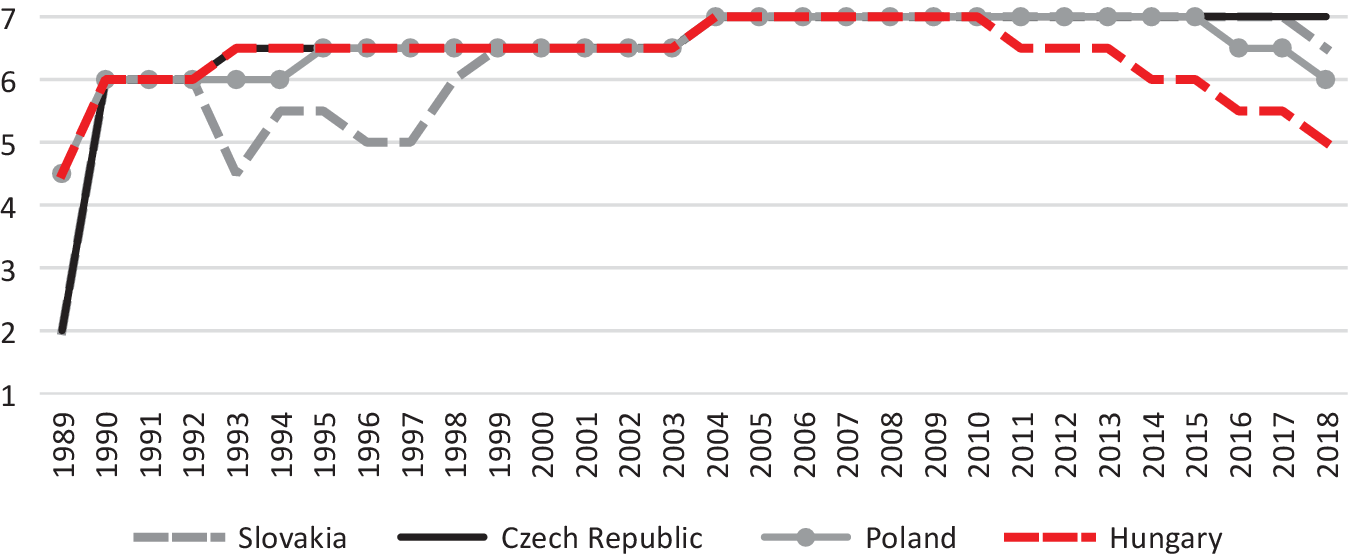

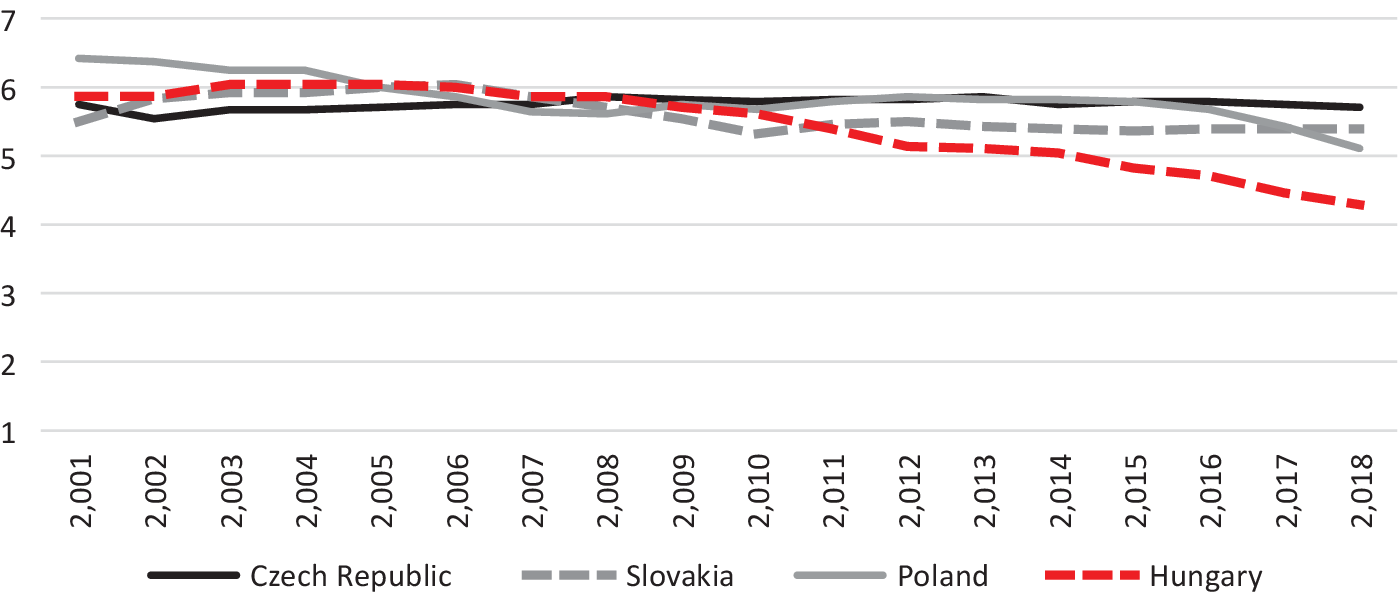

Finally, if democratic backsliding involves movement away from democracy, the definition of democracy matters. We use a mid-range procedural definition (Merkel Reference Merkel, Merkel and Kneip2018, 5–6): democratic backsliding means rolling back liberal democracy. Like the simpler electoral democracy, this entails free and fair elections, universal suffrage, and a free press but also rule of law and constraints on executive power. Liberal democracies thus feature (1) political rights: freedom of expression, association, and assembly; (2) civil liberties: protection of life, liberty, and property; (3) checks and balances, separation of powers between the legislature, executive, and judiciary; and (4) accountability of elected officials (Merkel Reference Merkel, Merkel and Kneip2018, 7–11). Since backsliding is a gradual process, it follows that states can be rated in terms of shades of grey. This is indeed the case for Central Europe (see figures 1 and 2, and Sitter et al. Reference Sitter, Batory, Kostka, Krizsan and Zentai2016). But we reserve the term substantial democratic backsliding for states where the governments have driven the process so far that they no longer fully qualify as liberal democracies.

Figure 1 Freedom in the World. Range 1–7 (inverted scale)

Figure 2 Nations in Transit. Range 1–7 (inverted scale)

Because research on Central Europe has used the term for various problems associated with real-life democracy, it is important to be clear about what democratic backsliding is not. First, it is not about low turn-out, weak links between parties and civic society, declining party membership, electoral volatility, fragile government coalitions, or low trust. Such quality-of-democracy problems are better captured by Peter Mair and Béla Greskovits’ concept hollowing out (Mair Reference Mair2013, 1; Greskovits Reference Greskovits2015, 28–29; see Buštíková and Guasti Reference Buštíková and Guasti2017 for an alternative concept). Second, democratic backsliding is not about backlash against economic or social liberalism, or the strength of populism (see e.g., Rupnik Reference Rupnik2007, 17–18; Krastev Reference Krastev2007, 56–67; Gati Reference Gati2007). Populist parties in government may well be more likely to initiate backsliding, but precisely therefore, populism should not be part of the definition. Neither should policies on gay marriage, sex education, abortion, or immigration (Dawson and Hanley Reference Dawson and Hanley2016, Reference Dawson and Hanley2019; Hanley and Vachudová Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018; Krastev Reference Krastev2016). As the Austrian and Italian experience shows, there is a difference between pursuing illiberal policies and breaking the rules of the game (see e.g., Rosenberger Reference Rosenberger, Ihl, Chéne, Vian and Waterlot2003; Urbinati Reference Urbinati2011). Only the latter constitutes democratic backsliding.

As we define it, democratic backsliding involves both formal and informal erosion of democracy along at least one of the three dimensions that are central to liberal democracy: political rights, free elections, and the rule of law. There is no single recipe: democratic backsliding can involve degradation on all three dimensions at the same time, sequentially, or even in isolation.

The most obvious form of democratic backsliding is restricting classical political rights: freedom of expression and assembly. Freedom of expression requires independent media. A government can exercise control of the media—print, broadcast, and online—directly through regulation and oversight, or more indirectly, e.g., by using state advertising to support government-friendly media. Freedom of assembly and association is fundamental for interest aggregation and articulation. A government can undermine independent civil society organizations, churches, universities, theatres, etc. through regulations and financial incentives (e.g., legislation, registration and reporting requirements, special tax or audit burdens), but also by informal or illegal practices.

Second, free and fair elections are the sine qua non of democracy. As Patrick Dunleavy (Reference Dunleavy1991) pointed out, winners are not simply awarded a prize. They win the power to change the conditions for the next race. Such changes are inevitably controversial; to qualify as backsliding they must be sufficiently one-sided and severe as to limit free and fair elections. A government can limit contestation by excluding specific parties or lists, through unfair campaign rules or media access, by abusing government resources for party campaigns, or even vote buying (Mares and Young Reference Mares and Young2019). Moreover, they can redesign the electoral system to disadvantage the opposition by changing constituencies, electoral thresholds, or formulas (in PR systems), or even electoral systems, and taking control of oversight institutions.

The third dimension of democratic backsliding reflects the importance of the rule of law as a fundamental component of (liberal) democracy; it requires horizontal separation of powers between the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary. Limiting the legislatures’ power to debate, amend or review laws, and hold the executive to account, can—if taken to extremes—limit democracy. This includes the “lock-in” of policies through constitutional reform, barring an alternative majority from reversing them in the future. The executive can take control of public administration through personnel purges, nepotism, clientelism, or corruption, and thus blur the boundaries of party and state. In the EU, the most serious charges center on member states’ undermining judicial independence. Governments can employ a range of measures to do this, including unilateral changes in the scope, remit, and competence of the constitutional court or lower courts; rules and procedures for judicial review; procedures for appointing judges; personnel purges; and even ignoring or unconstitutionally overturning court rulings or suspending the constitution.

Assessing Democratic Backsliding in the Visegrád Four, 2010–2019

There is broad scholarly consensus that substantial democratic backsliding has been going on since 2010 in Hungary and since 2015 in Poland. Both governments increased political control of the media and curtailed the freedom of civil society, distorted the electoral process, and limited the power and independence of the judiciary. Although acquisition of media by local oligarchs and corrupt dealings between politics and business caused concern also in the other two Visegrád states, developments in the Czech Republic and Slovakia were closer to Silvio Berlusconi’s Italy than Viktor Orbán’s Hungary. This is reflected in democracy indices, including Polity IV, Freedom House (figure 1), Nations in Transit (figure 2) and Bertelsmann Transformation Index (Merkel Reference Merkel, Bakke and Peters2011, 65–67, 69).Footnote 5 Their trajectories in the 1990s differed, with the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland as frontrunners and Slovakia as a laggard. Freedom House downgraded Slovakia from Free (as a part of Czechoslovakia) to Partly Free in the first year of independence, citing “the government’s mistreatment of ethnic minorities and its crackdown on the independence of the media” (Freedom in the World 1993–1994, 88).Footnote 6 Slovakia under Mečiar was described as belated transition, or in Soňa Szomolányi’s (Reference Szomolányi1999) terms, on a “winding road” to democracy.

In this section, we map democratic degradation since 2010. To flesh out the discussion of what qualifies as backsliding and help explain the lack of substantial backsliding in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, we also describe an earlier failed attempt to rig the Czech electoral system and the actions of the third Mečiar government (1994–1998). The Hungarian case is outlined first along each of the three dimensions. As the most extreme case, it serves as a benchmark for the other three.

Backsliding on Political Rights: Free Media and Independent Civil Society

The new 2010 Fidesz government earned widespread criticism for legislation and government practices that curtailed the freedom of the press. Much like Mečiar before it, and PiS after it, Fidesz turned state-run media into a veritable government propaganda machine by populating editorial boards and oversight organs with their own people (Lebovič Reference Lebovič, Bútora, Mesežnikov and Bútorová1999, 23; Nations in Transit, Hungary country reports, 2011–2018, and Poland country reports 2015–2018). However, while private broadcasters in Slovakia tended to support the anti-Mečiar opposition and independent newspapers continued to operate, Orbán’s allies took control of most national and regional newspapers. The leading daily Népszabadság was liquidated in a hostile takeover in 2016, and the last remaining opposition daily of any stature, Magyar Nemzet, folded in 2018. Although the building of a Fidesz-loyal media empire through (ab)use of state funds had already started under the first Orbán government (1998–2002) it was not until the 2010s that Fidesz was in a strong enough position to significantly reduce media pluralism (Bátorfy and Urbán Reference Bátorfy and Urbán2020, 49ff.). PiS followed Fidesz’s tactic of using state advertising money and subsidies to support pro-government media and to punish critical media, but was unable to proceed as far as Fidesz in terms of ownership restructuring because a substantial share of Poland’s print media was foreign-owned.

While state-run media remained quite balanced, acquisitions of newspapers and media companies by local oligarchs and investment groups caused concerns in the Czech Republic and Slovakia (Lyman Reference Lyman2014). Just as its owner Andrej Babiš entered politics in 2013, the Agrofert group bought MAFRA, one of the biggest Czech publishing houses. In Slovakia, the Penta group (linked to high-level corruption in the “Gorilla files”) bought a large share of Petit Press in 2014, but later sold down to a minority position. In both cases editors of flagship newspapers resigned in protest. An audio clip posted anonymously on Twitter in 2017 suggested that there were reasons for concern, as Babiš was caught on tape colluding with a journalist from one of the MAFRA newspapers to smear political opponents (Kmenta Reference Kmenta2017, 32, 40, 263; Kopeček Reference Kopeček, Kopeček, Hloušek, Chytilek and Svačinová2018, 126–27). Yet Czech media remains pluralist, and mainly driven by profit motives (Jirák & Köpplová Reference Jirák, Köpplová, Lorenz and Formánková2019). In Slovakia, Kuciak’s murder sent shock waves through the political landscape and caused Freedom House (2019) to reduce Slovakia’s freedom of expression score. Kuciak had been working on an article on embezzlement of EU funds and alleged links between Italian mafia and top Smer politicians. This came on top of a generally bad relationship between Fico and the media, with the prime minister calling journalists “filthy anti-Slovak prostitutes.” Fico resigned amid large protests in March 2018. Marián Kočner, a Slovak businessman suspected of links to organized crime, was indicted for having ordered the murders in 2019 and stood trial as the present article went to press.

Moving beyond the media, Hungary went far beyond its three neighbors when it came to attacking civil society. The most blatant measure, which contributed to Fidesz’s suspension from the EPP, was the so-called “Stop Soros” law of 2018, which criminalized NGO activities that could be seen as supporting asylum applicants (the European Commission subsequently referred this to the European Court of Justice). This was preceded by a series of measures that limited the independence of universities (2017), restricted religious organizations (2011), and stigmatized NGOs that receive foreign funding (2017). The government also carried out a series of “information campaigns” against George Soros, the EU, and the UN, where the Hungarian-born U.S. billionaire was portrayed as being bent on destroying Hungarian ethnic homogeneity (Batory and Svensson Reference Batory and Svensson2019; Benková Reference Benková2019). In 2019 Central European University was expelled from the country, when a law prohibiting the enrolment of new students took effect (Corbett and Gordon Reference Corbett and Gordon2018; Enyedi Reference Enyedi2018). The Czech Republic and Slovakia saw no comparable measures, but in Poland the turn toward Hungarian-style illiberal democracy hit civil society in 2016 with new laws that that limited access to public funds, established a government-controlled National Institute for Freedom (attached to the prime minister’s office) to distribute funds, and criminalized discussions of Polish individuals’ role in the holocaust. These measures were widely seen as an effort to limit the independence of PiS-critical civil society (Helsinki Foundation 2017).

Backsliding on Free and Fair Elections: Rules, Finance, and Procedures

Like most liberal democracies, all four Visegrád states have amended their electoral laws. As in many other European cases, controversies arose over party finance. Unlike other EU states, however, the Fidesz and PiS governments took control of the electoral process. The Hungarian reform of 2011 was an extreme case of unilateral, tailor-made, electoral reform. Before the 2014 election, the government made substantial changes to the electoral system and campaign financing rules, without consulting the opposition. While keeping the mixed electoral system, it reduced the number of seats, increased the share contested in single member districts, introduced a first-past-the-post system for these constituencies, redrew constituency boundaries, and changed the appointment rules for the electoral commission. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe criticized both the 2014 and 2018 elections as free but not fair, giving the governing party an undue advantage (OSCE 2014, 2018). This was based on Fidesz’s manipulating the electoral system to serve its own interests; blurring the boundaries between state and party; restricting the room for political debate; and preventing voters from making informed choices. This was as much about political control of the process as the biased electoral law. New campaign finance rules gave rise to frivolous parties with names suspiciously similar to major opposition parties. The government and its allies controlled the media as well as public advertising space (Nations in Transit 2018). Before the 2018 election, Fidesz even passed a billboard law against political ads outside the official campaign period, while allowing government “public interest” ads (in effect, government/party propaganda). Fidesz probably would have won under the old system, but secured a supermajority thanks to the new laws.

In Poland, the biggest problem in terms of free and fair elections was the government’s taking control of the oversight of the electoral process, by making sure the National Electoral Office was appointed unilaterally by PiS in 2018 (Nations in Transit, Poland, 2018, 7). Outgoing Electoral Commission president Wojciech Hermeliński described this as “a return of the electoral commission to the times of the Polish People’s Republic” (Financial Times 2019b). Previous electoral reforms—before almost every election between 1991 and 2005—had been adopted by majorities that transcended the government-opposition divide (Benoit and Hayden Reference Benoit and Hayden2004).

The Czech Republic and Slovakia have had their fair share of controversies over electoral reforms (Charvát et al. Reference Charvát2015), but no Fidesz-style attempt to take control of the entire process. In Slovakia, Mečiar’s Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS) certainly wished for a majoritarian or a mixed system, but the two much smaller junior coalition partners refused. In the end, even the attempt to skew competition by raising the electoral threshold for alliances backfired: the opposition registered their alliances as parties, won the election and reversed the controversial parts of the reform (Lebovič Reference Lebovič, Bútora, Mesežnikov and Bútorová1999, 31–33). Having won the 2012 election, Fico was in the position to change the electoral system for parliamentary elections unilaterally, but chose not to.Footnote 7

Czech scholars have long advocated a more disproportional electoral system to make it easier to form stable governments. Petr Fiala (Reference Fiala, Novák and Lebeda2004), political science professor and present chairman of the Civic Democrats, is but one. In 1998 his party entered into the much criticized “opposition agreement” with the Social Democrats, in which the two rivals agreed to change the electoral system of the lower house from PR to majoritarian. However, they failed to use their constitution-altering majority before the death of a senator deprived them of this power, and their subsequent attempt to circumvent the Constitution by making the PR system less proportional was struck down by the Constitutional Court on President Havel’s initiative (Roberts Reference Roberts2003). The ruling sent an important signal: to change the electoral system, you first have to win a constitutional majority in both chambers. In 2017, Andrej Babiš was therefore well aware that his “dream” of a parliament with 101 MPs elected according to the first-past-the-post system was just a dream. He made clear on election night that it was “not a priority,” and it was not even part of ANO’s program (Babiš Reference Babiš2017; Info.cz 2017; Kopeček Reference Kopeček, Kopeček, Hloušek, Chytilek and Svačinová2018, 132).

Finally, Czech president Miloš Zeman’s appointing of a technocratic government in 2013 against the will of the parliamentary majority has been widely interpreted as an attempt to turn the country’s parliamentary democracy into a semi-presidential system (Brunclík and Kubat Reference Brunclík and Kubát2017; Dawson & Hanley Reference Dawson and Hanley2016; Hanley and Vachudová Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018). However, it turned out that the Czech president had no real power to aggrandize, and the attempt was easily contained. This episode is thus not an example of backsliding; it showed that democratic checks and balances worked.

Backsliding on Rule of Law: Executive and Judiciary Power

Attacks on checks and balances, the independence of the judiciary, and control of public administration were key elements of backsliding in Hungary and Poland. Both governments used parliamentary procedures to decrease debate and scrutiny of new legislation. Fidesz used its two-thirds majority to introduce a new constitution, limited the power of the constitutional court, and populated state institutions with its own people, all under the pretext of (post-communist) reform (Zemandl Reference Zemandl2017). The 2011 constitution (like the earlier mentioned electoral law) was pushed through as a private member bill, requiring a minimum of debate and scrutiny. The government’s subsequent use of constitutional amendments and “Cardinal Laws” (which can only be changed by a super-majority) drew sharp criticism from the EU Commission president (European Commission 2013). In 2011 the Commission censured the government for prematurely terminating the term of the president of the Supreme Court and lowering the compulsory retirement age for judges from 70 to 62, thus opening the way for 274 new appointments (Batory Reference Batory2016a). At the same time, a new system was put in place for the appointment of judges and allocation of cases, concentrating power in the hands of the president of a new National Judicial Office—Tünde Handó, whose husband was a member of the small Fidesz leadership circle. In 2019 Handó was appointed to the Constitutional Court.

Judicial reform is the one area where PiS matched—and even surpassed—Fidesz in terms of ambition and speed (Pech and Scheppele Reference Pech and Scheppele2017; Pech and Wachowiec Reference Pech and Wachowiec2020). Although the Polish government lacked the supermajority to lock in changes through constitution reform, it made up for this by using its parliamentary majority to pass four laws on judiciary reform in 2017. It prematurely terminated the term of the president of the Supreme Court and lowered the compulsory retirement age for judges, resulting in the replacement of 40% of the Supreme Court judges. Following the example of Fidesz, and before that, Mečiar, PiS used its power to install its own people in important public positions in the civil service, state intelligence, the general prosecutor’s office, state companies, and bodies involved in state procurement (Galanda, Földesová, and Benedik 1999, 85; Nations in Transit, Poland, 2016, 2, 2017, 4; Nations in Transit, Hungary 2018, 2). The law on the National Council of the Judiciary—the oversight organ—granted a parliamentary majority the right to appoint the members. President Andrzej Duda vetoed the original bills on the Supreme Court and the National Council of the Judiciary amid large-scale protests; however, the EU and the Venice Commission found that even the revised laws threatened juridical independence, separation of powers, and the rule of law (Nations in Transit country reports, Poland, 2018, 2). In November 2019, the European Court of Justice ruled that the National Council of the Judiciary lacked the independence to safeguard the independence of the judiciary; in 2020 Judge Paweł Juszczyszyn was suspended on reduced pay for seeking to implement the ECJ verdict (Pech and Kelemen Reference Pech and Kelemen2020).

Rule of law and separation of powers is perhaps where Mečiar’s Slovakia deviated most from the backsliding template of the last decade. Although the Constitutional Court was an important counter-majority force (Kosař, Baroš, and Dufek Reference Kosař, Baroš and Dufek2019, 446), the government did not seek to control the court by replacing its members. It just ignored rulings it did not like. Unlike Fidesz and PiS, Mečiar did not have a “tame” president. He therefore tried to curb presidential power in every way possible, including stripping the president of powers that were not granted by the constitution, slashing his budget and staff, and with the help of the State Intelligence Service, even kidnapping his son (Freedom House country report, Slovakia, 1995–1996, 419).

As 2019 came to an end, the independence of the judiciary and the Constitutional Court in the Czech Republic and Slovakia was not under government attack, and popular trust in the independence of courts was on the rise (EU Justice Scoreboard 2019). This is not to say that there were not controversies. In Prague, Babiš was accused of putting pressure on police investigating the “Stork’s Nest” case, and of replacing the minister of justice to ensure that he would not be prosecuted. If that was his intention, it did not work: the chief public prosecutor reopened the case in December 2019 (Politico 2019). Meanwhile in Slovakia, the parliament failed to nominate any candidates to succeed the nine judges whose term expired in February 2019. Fico, a lawyer by profession, had his eyes set on the Constitutional Court presidency. He did not even get the support of his coalition partners. This was no government attempt to disable the court; on the contrary, Smer Prime Minister Peter Pellegrini criticized his own party caucus for failing to nominate the necessary number of candidates (TASR 2019). Although appointment of Constitutional Court judges became more politicized in both countries, this is a far cry from the kind of attack on the judiciary seen in Hungary and Poland. In the Czech Republic, it was the opposition on the center-right (which controlled the Senate) that used the opportunity to get back at president Zeman by turning down a candidate whose professional credentials nobody doubted (Januš 2019).

Explaining Backsliding: Motive, Opportunity, and Opposition

This section turns to why Hungary and Poland have been backsliding since 2010 and 2015; why Smer did not initiate backsliding in 2012; and why there was little substantial backsliding in the Czech Republic. The core argument is that democratic backsliding requires motive, opportunity, and the absence of constraints. If backsliding involves deliberate acts by democratically elected governments to undermine the fundamental rules of liberal democracy, it is a policy choice. And policies need motives. The classical party politics literature focuses on politicians’ quest for power in order to implement policies, as well as power for its own sake or for the sake of enrichment. But in order to achieve their goals, parties must win office. In unicameral parliamentary systems, like those of Hungary and Slovakia, this means winning a simple parliamentary majority in a single election. In bi-cameral or (semi-)presidential systems, it involves the somewhat more difficult task of winning in multiple arenas—as is the case in Poland and the Czech Republic. In addition, many constitutions require super-majorities for constitutional change—a two-thirds parliamentary majority in Hungary, the same plus an absolute majority in the Senate in Poland, a three-fifths majority in Slovakia, and the same in both houses in the Czech case. Finally, the most important constraints are the opposition parties, which might threaten defeat in the next election; domestic courts, which might rule new laws unconstitutional; and the EU, which might impose costs on governments that break fundamental EU rules and values.

Motive: Populism, Policy, and Power

One ideological factor unites Orbán, Kaczyński, Fico, and Babiš—populism. All four lead more or less populist parties. In the Hungarian and Polish case, they draw heavily on ethnic nationalism, and paint their main opponents as the heirs of the pre-1989 communists and apparatchiks. PiS and Fidesz thus qualify as fully populist in the sense of claiming to represent the pure and true people against the corrupt elite (Taggart Reference Taggart2000). Both subscribe to a “winner takes all” approach to democracy (not unlike that of Mečiar). Whereas mainstream democratic parties see themselves as the temporary custodians of limited power, these leaders interpreted their victories as a mandate to exercise absolute power. Careful reading of the rhetoric and action of Viktor Orbán and Jarosław Kaczyński showed this well before their winning power in 2010 and 2015 respectively (Lendvai Reference Lendvai2017; Szczerbiak Reference Szczerbiak2016; Financial Times 2016). Only after winning re-election in 2014, with a new constitution and tailor-made electoral system, did the Hungarian prime minister set out what he labelled an “illiberal” ideology as an alternative to liberal democracy (Orbán Reference Orbán2014). In Poland, Kaczyński played up his ideological kinship with Orbán after the election victory, no doubt partly to ensure that the two would protect each other against any action from the EU (which requires a unanimous vote among the other member states to suspend aspects of a country’s membership). In terms of policy, Fidesz and PiS followed the classic populist recipe, rapidly introducing policies that were widely described as Christian national, populist, or socially conservative, and economically protectionist, with the added proviso that those advocating alternatives to these policies would be against the true will of the nation. Populist ideology and policy could therefore be assigned a large role in motivation for backsliding.

Smer and ANO represent a different kind of populism—one that is more centrist and technocratic (Učeň Reference Učeň2007; Buštíková and Guasti Reference Buštíková and Guasti2018), even if lack of tolerance and restraint is striking in these cases too. To be sure, Fico did not shy away from nationalist rhetoric. Yet his attempt to use the migration crisis in the 2016 electoral campaign backfired, partly because of competition from the extreme right Kotleba party.Footnote 8 While Babiš qualifies as a populist in terms of his rhetoric directed against corrupt and incompetent traditional party elites (Hanley and Vachudova Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018), he had an even weaker ideological agenda than Fico, and is manifestly not a Czech nationalist (Kopeček Reference Kopeček, Kopeček, Hloušek, Chytilek and Svačinová2018, 97, 129–132). Although he is on record as admiring Orbán’s “untrammelled authority” (Hanley and Vachudová Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018, 282), neither Babiš nor Fico reject liberal democracy. In 2013, Babiš outsourced the compiling of a program to a public relations company (Bakke Reference Bakke and Malnes2017). If he aspired to weaken democratic checks and balances, he also followed his Hungarian role model in playing this down until he could secure full power. ANO thus comes closer to the West European center-right populism found in Italy: in the words of Dalibor Roháč (Reference Roháč2017), “by far the most pressing risk facing the Czech Republic is not authoritarianism, but rather following a path similar to that of Italy under Silvio Berlusconi’s successive governments.” In contrast, when comparing Berlusconi and Orbán, Körösényi and Patkós (Reference Körösényi and Patkós2015) distinguished between the former’s liberal populism and the latter’s illiberal populism.

The Babiš-Berlusconi parallel draws attention to the second set of motives for democratic backsliding—to hold on to power. Europe is full of career politicians for whom gaining office is the measure of success. In a few cases, their motivation is also to protect economic interests or accumulate wealth. Rent-seeking and corruption has been a problem in all four Visegrád states: in the 1990s privatization and restitution of state property offered ample opportunities for corruption, and after EU accession Structural Funds played similar role (Gassebner, Lamla, and Vreeland Reference Gassebner, Lamla and Vreeland2012; Sitter and Bakke Reference Sitter, Bakke and Laursen2019; Guasti and Mansfeldová Reference Guasti, Mansfeldová, Guasti and Mansfeldová2018; see also Dvořáková Reference Dvořáková2012). Hungary provides the clearest example of what Bálint Magyar (Reference Magyar2016) labelled the “post-communist mafia state”: distributing EU funds to supporters in more or less corrupt schemes was the central element in Fidesz’s effort to build a supportive oligarchy and a “new national middle class.” Critics described the relationship between the ruling elite and its oligarchs as reverse state capture, where Fidesz set up corruption networks and secured political control of the prosecutor’s office to ensure that it went unpunished (Nations in Transit, Hungary country report 2018, 12). In 2018, Forbes rated Orbán’s childhood friend, the gas fitter Lőrinc Mészáros, as the richest individual in Hungary (Index 2019). This gave rise to an extreme version of the office-seeking party: the far right Jobbik party built its electoral campaign in 2018 around the promise that if Fidesz lost the election, its leaders and oligarchs would be prosecuted.

In the Czech Republic and Slovakia, practically all government parties have been involved in corruption scandals. In Slovakia, some of the HZDS oligarchs that had benefited from government control of the National Property Fund allegedly transferred their allegiance to Robert Fico’s Smer when they realized that HZDS was a spent force (Vagovič Reference Vagovič2016, 7). Corruption associated with public procurement has been rampant. As in the other three states, abuse of EU agricultural funding was an endemic problem (New York Times 2019); the murder of Slovak journalist Jan Kuciak in 2018 was linked to his investigation of organized crime and corruption associated with such funds. In the Czech Republic, a party finance scandal brought down the second Václav Klaus government, and oligarch links with the Civic Democrats and the Social Democrats are well documented (Klíma Reference Klíma2015). In Italy, Berlusconi famously used political power to protect and enhance his media and financial empire (Ginsborg Reference Ginsborg2004); according to Kopeček (Reference Kopeček, Kopeček, Hloušek, Chytilek and Svačinová2018, 95) one of Babiš’ motives for entering politics was precisely to protect his economic interests. Accusations of embezzlement of EU subsidies marred his premiership. When the European Commission in 2019 found him in breach of EU conflict of interest rules and threatened to suspend EU funding, this prompted the “Million Moments for Democracy” civic group to organize demonstrations attended by some 250,000 people. The crowds demanded Babiš’ resignation and that Agrofert be cut off from EU funds (Reuters 2019).

The Polish case is less clear cut, because most of the high-profile corruption cases are linked to party finance rather than personal enrichment. Poland’s dollar-billionaires do not have the close links to the party elite that Mészáros has to Fidesz. The country ranks third, after Romania and Hungary, on OLAF’s 2017 list of investigations of misuse of EU funds (European Anti-Fraud Office 2018), but still had the best score on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index of the Visegrád four in 2018. Whereas the quest for wealth and power carries more explanatory weight in the Czech and Slovak cases, and Fidesz’s motivation draws on both, in the Polish case the motivation for backsliding thus appeared to be linked more strongly to ideology and policy.

Opportunity: Elections, Majorities, and Super-Majorities

If backsliding involves deliberate acts by democratically elected governments to undermine the fundamental rules of liberal democracy, its starting point is an electoral victory. The biggest obstacle to democratic backsliding is that political parties with this kind of political agenda rarely win power in free elections in liberal democracies. Indeed, neither Fidesz in 2010 nor PiS in 2015 ran on platforms that even hinted at the radical de-democratization they would pursue. Both Orbán (1998–2002) and Kaczyński (2006–2007) had previously served as prime ministers in coalition governments. Fidesz’s 2006 and 2010 election campaigns centered on economic issues such as unemployment, wages and pensions, and the need for a change of government. In 2010, Fidesz’s victory came on the back of economic crisis, corruption scandals, and dissatisfaction with the economic transition. The MSzP also suffered government fatigue after two terms in power, particularly after a leaked speech in which Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány admitted lying about the economy in the 2006 campaign (Sitter Reference Sitter, Bakke and Peters2011). Likewise, PiS won the 2015 elections on populist socio-economic issues, in this case increased child benefits and lower retirement age. Moderate PiS politicians like Beata Szydło fronted the party during the campaign, while the controversial party chairman Jarosław Kaczyński assumed a backstage role (Szczerbiak Reference Szczerbiak2016; Markowski Reference Markowski, Guasti and Mansfeldová2018). Like Fidesz, PiS benefitted from a fragmented set of rivals and an unpopular incumbent government. The functional equivalent of Gyurcsány’s “we lied” speech was the “Waitergate” scandal, which involved indiscretions of top government politicians caught on tape in fancy Warsaw restaurants. The key factor that turned a 38% plurality into a majority in 2015 was the failure of the divided left and the extreme right to win any seats. In 2019, facing a better organized opposition, PiS won the lower house, but lost control of the senate.

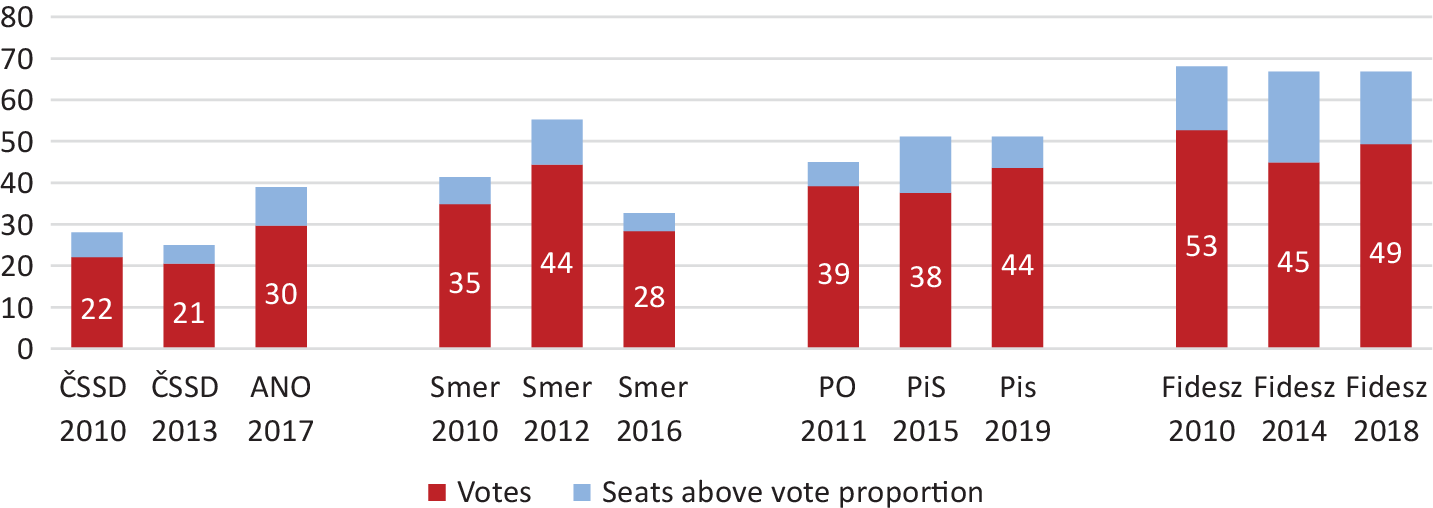

The surprise in the Hungarian 2010 election was not the Fidesz victory, but that 53% of the vote gave the party a two-thirds majority in parliament. In 1990, with an emergent six-party system, the combination of a mixed electoral system and the two-thirds threshold for constitutional change looked like a reasonable safeguard. By the end of 2006, Fidesz had absorbed large parts of the other three “bourgeois” parties and was left almost alone in opposition to the re-elected MSzP-SzDSz coalition. Winning executive office is a necessary condition for democratic backsliding; a parliamentary majority makes it easier; but control of a super-majority in 2010 rendered Fidesz unstoppable. When the government secured re-election in 2014 and 2018, its illiberal program was much clearer. But by then the party had taken control of state (and much private) media and made the electoral system more disproportional (Batory Reference Batory2016b). Without the ability to adopt a new constitution and amend it as it saw fit, reform the judiciary, change the electoral law, and lock in future changes through Cardinal Laws, Fidesz’s backsliding project would have been much more difficult to sustain. Although many of the laws that centralized government power over the media and civil society were adopted as ordinary laws, Fidesz’s super-majority meant that the chances of the president or the Constitutional Court reversing laws that involved democratic backsliding were slim.

Smer, PiS, and ANO never had Fidesz’s exceptional opportunity. Smer’s landslide victory in 2012 raised fears that Fico might follow in Orbán’s footsteps (Spiegel 2012). Like Fidesz, it won the election on a campaign that focused on socio-economic issues and presented Smer as the guarantor of stability, helped by a corruption and surveillance scandal (the “Gorilla files,” which involved the 2002–2006 center-right coalition, and, as it later turned out, Fico as well). But Fico took another course and invited all the other parties to coalition talks. They declined. Although Smer did not have the two-thirds super-majority needed to change the Constitution unilaterally, it had the power to change the electoral system. Yet Fico declared that there would be no major changes in the electoral system without opposition agreement (Spáč Reference Spáč2014). One interpretation is that Fico did not aim to backslide. Another is that he had intended to concentrate power (Mesežnikov Reference Mesežnikov2015), but backed down after losing the presidential election to Andrej Kiska in 2014. Whatever his motivation, electoral reform was risky. Given high electoral volatility, no party could be certain of its future support. Even if Fico followed Orbán’s example and introduced a majoritarian electoral system, it might backfire. This became abundantly clear in 2017, when regional governors were elected with a first-past-the-post system: Smer lost every single contest. Indeed, the victory of the rainbow coalition against HZDS in 1998 had shown what a united opposition could achieve. Slovakia’s experience with backsliding under Mečiar seems to have put Slovak society into a perpetual state of alarm, where any sign of power concentration triggers a counter-reaction. This was the case when the liberal Zuzana Čaputová beat Smer-supported Maroš Šefčovič in the March 2019 presidential election.

The Polish and Czech cases direct attention to the role of the second chamber. After its 2015 victory, PiS lost no time in emulating Fidesz. However, its backsliding came off to a much more difficult start because it did not win constitution-altering powers. This left the Constitutional Court in a stronger position to fight back, and the EU in a better position to defend the Polish judiciary. In the meantime, the European Commission had also learned some lessons about the limited effect of cautious handling of backsliding, and equipped itself with the new Rule of Law Framework (Sitter and Bakke Reference Sitter, Bakke and Laursen2019). PiS’ loss of the senate in 2019 made it more difficult even to pass ordinary legislation. The Czech case is simpler, because there was no majority power for ANO to abuse. In 2017 the party won seventy-eight of two hundred seats in the lower house, and as per 2020 it controlled only seven of eighty-one senators. This was not merely a result of the vote distribution in a given year, but a systemic feature of the Czech system. Because elections to the Senate are held over a staggered period, with one-third elected every other year, and constitutional change requires three-fifths majorities in both houses, even a landslide election is very unlikely to give any party constitution-altering power. Moreover, the senate’s two-round run-off system favors centrist candidates. In addition, because PR elections to the lower house are written into the Constitution, electoral system change is difficult, as the failed attempt in the 1998–2002 period to introduce a majoritarian system showed. Whether Babiš is a Berlusconi or an Orbán was a moot point as long as he lacked the power to emulate Fidesz.

Opposition: Will, Power, and Strategy

Our analysis of motive and opportunity suggests that democratic backsliding can be a vicious cycle. For a strongly motivated party, a single opportunity to alter the constitution and change the rules of the game can yield new opportunities for further backsliding. Fidesz’s democratic backsliding during the 2010–2014 parliament gave it the control of the electoral process and the media dominance it needed to secure further super-majorities with lower shares of the vote in 2014 and 2018 (figure 3). It was no accident that the first steps taken by Fidesz and PiS involved efforts to limit the powers of the judiciary. The contrast between Fidesz’s successful takeover of the judiciary and the struggle between the PiS government and the Polish constitutional court during the 2015–2019 parliament illustrated the role of one of the three actors best placed to oppose or constrain democratic backsliding. To the extent that democratic backsliding involves breaking the national constitution, the most direct constraints on backsliding rest in the hands of the national constitutional court (Kosař, Baroš, and Dufek Reference Kosař, Baroš and Dufek2019). Two other constraints—the opposition and the European Union—operate more indirectly.

Figure 3 Shares of votes compared to shares of seats, V4 elections 2010–2019

If democratic backsliding is ultimately about the offending party retaining power, the “democratic opposition” can be a constraint on backsliding. In contrast to actual authoritarian regimes, or even “competitive authoritarianism” (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2002, Kelemen Reference Kelemen2017), democratic backsliding involves a risk that the backsliding government loses an election. In the end, Mečiar’s backsliding project failed primarily because the other parties united against him, although EU pressure helped (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2005). In 2010 and 2015 Orbán and Kaczyński benefitted from a fragmented opposition to an extent that Babiš and Fico never did. But majoritarian systems—even gerrymandered ones—are vulnerable to changes in opposition strategy. In 2006, Berlusconi lost the election with a tailor-made electoral law (which the constitutional court eventually declared unconstitutional in 2013). On October 13, 2019, PiS met a milder version of Berlusconi and Mečiar’s fate when Kaczyński’s party lost control of the senate. The very same day, Fidesz lost the Budapest mayoral race to a united opposition. In the 2014 and 2018 elections opposition disunity played directly into Orbán’s hands, making the limits to free and fair elections less relevant. Although Orbán could easily dismiss the policy importance of Gergely Karácsony’s Budapest victory, his mayoral election drove home a more important political message: short of a fully blown “competitive authoritarian” model, democratic backsliding is an open-ended and potentially reversible process. Until the end of 2019, backsliding in Hungary and Poland had been possible partly because the weakness and disunity of the opposition removed a significant constraint on Orbán and Kaczyński—the threat of electoral defeat.

Finally, for EU member states, the EU itself represents a potential constraint on backsliding. As of 2020, however, the EU had failed to live up to expectations that it might limit or reverse democratic backsliding (Sedelmeier Reference Sedelmeier2017, Sitter and Bakke Reference Sitter, Bakke and Laursen2019). Part of the problem lay in the EU’s limited policy tools. But, as Daniel Kelemen (Reference Kelemen2017) argues, the main problem was one of political will—among governments that were sympathetic to Fidesz and PiS, among MEPs from the European People’s Party, and among EPP-appointed Commissioners. The EU’s ultimate sanction—suspension of important aspects of EU membership under the procedure laid out in Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union—requires unanimity among the remaining member states. This was not merely a matter of Poland and Hungary protecting each other. When EU ambassadors voted informally on whether to consider an Article 7 move against Poland in 2017, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Croatia voted against, while Austria, Romania, Italy, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Slovenia, the UK, and Bulgaria abstained. Likewise, ordinary mechanisms for dealing with states that break EU laws proved inadequate because the Commission opted for a two-track strategy of admonishing Fidesz but choosing infringement procedures that allowed the government to make minor amends. The dismissal of judges was dealt with as a matter of age discrimination, which allowed the Hungarian government to compensate the dismissed judges rather than reinstate them (Batory Reference Batory2016a). Even after the Commission adopted the Rule of Law Framework in 2014, Polish prime minister Beata Szydło simply dismissed the Commission’s Rule of Law Recommendations (European Commission 2017). However, in 2018 and 2019 the European Court of Justice found the dismissal of Polish constitutional and ordinary judges by way of early retirement in breach of EU law, this time also citing the negative effect on the independence of the judiciary. As in the case of the fragmented opposition, the very cautious approach the EU took to dealing with democratic backsliding in the decade following Fidesz’s 2010 victory removed an important potential constraint on backsliding in this crucial period. However, after a decade’s experience, the Commission began to explore new ways of constraining backsliding, including linking EU funding to compliance with the rule of law (Scheppele, Pech, and Keleman Reference Scheppele, Pech and Daniel Kelemen2018; Sitter and Bakke Reference Sitter, Bakke and Laursen2019).

Conclusion: Containing the EU’s Enfants Terribles

Democratic backsliding is a serious problem both for the states where it occurs and for the EU. But the situation is not as desperate as some commentators would have it. As of 2020, Hungary had clearly crossed the line and left liberal democracy behind. The PiS government in Poland had gone far down a similar track, but the EU had woken up to the danger. The Commission began to explore new policy tools for dealing with rule-of-law violations, such as withholding EU funding. On the other hand, although the Czech Republic and Slovakia had serious problems with corruption and media freedom, they remained a long way away from the serious and substantial democratic backsliding seen in Poland and Hungary. In terms of freedom of association, free and fair elections, centralization of executive power, and independence of the judiciary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia remained more or less ordinary liberal democracies—albeit featuring some of the problems that made Italy a “difficult democracy.” Babiš and Zeman might have dreamt about, and even attempted, abusing power, but the same charge was levelled against Boris Johnson. As in the British case, they ran up against institutional constraints. As Timothy Garton Ash (Reference Ash2019) soberly put it in October 2019:

Only in Hungary, however, has the erosion of democracy gone so far that it is difficult to envisage even the best-organized opposition party winning a national election anytime soon. Everywhere else in the region there are still regular, free, and relatively fair elections. As in America, as in Britain, as in every other imperfect democracy—and which is not imperfect?—the challenge throughout Central Europe is to find the party, the program, and the leaders to win that next election. They have our problems now.

If the Hungarian and Polish cases show the seriousness of backsliding, the Czech and Slovak cases demonstrate that the situation is far from desperate. The Hungarian case was exceptional. Fidesz’s ability to change the regime was contingent on a “perfect storm” that combined a parliamentary super-majority with a weak constitution, a supportive president, a fragmented opposition, an over-cautious European Commission, and a protective EU-level political party. Fidesz’s two-thirds majority allowed it to circumvent all constitutional safeguards, while parts of the opposition and many actors at the EU-level failed to appreciate the real danger of democratic backsliding. By 2020, the situation in Poland was serious, but somewhat more precarious. PiS not only lacked extraordinary constitution-altering powers, but had lost control of the senate. It faced a more assertive European Commission. Whereas Fidesz enjoyed a considerable degree of protection due to its status as a member of the European People’s Party, PiS had no political shield. The adage than once (Mečiar) is an accident, twice (Orbán) is a coincidence, and three times (Kaczyński) suggests a pattern does not quite hold in this case. Although the PiS government pushed through measures that amounted to serious democratic backsliding, the conditions for further backsliding were much less favorable there than in Hungary, independent media and civil society were stronger, and its opponents were better organized (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2019).

The Czech and Slovak cases, moreover, show the limits to backsliding that lack of opportunity and strong opposition might provide. Whatever their motives, Babiš and Fico (after 2016) did not have the parliamentary majority to embark on serious backsliding, let alone the power to change the constitution. There is nothing to suggest that they will win such a majority in the near future. Opposition parties mobilized against efforts to centralize power, and people took to the streets in huge numbers. Coalition partners refused to go along with initiatives that could have led to backsliding. If anything, Slovak politics seems to have been “inoculated” by the Mečiar experience: parties and voters respond quickly to punish potential backsliders. Although the two governments showed sympathy and support for their backsliding neighbors (notably when they joined with Italy to block Frans Timmermans’ appointment as Commission President in July 2019), careful analysis of domestic politics and political institutions should allay any fears that these two countries might be pushed down the illiberal path if the EU acts too strongly against Poland and Hungary. Consequently, the risk that the “hollowing out” of democracy that these two states had experienced by early 2020 might develop into serious democratic backsliding hinges both on domestic institutions, political parties’ strategies, the voters’ reactions, and on the EU’s will and capacity to address the backsliding problem in Poland and Hungary.

The overall conclusion from comparing the four cases is that democratic backsliding is more precarious than much of the recent literature suggests. This is not to play down the seriousness of backsliding in Poland and Hungary. From a liberal democratic point of view, both cases are of course very problematic. Neither is this to trivialize the problems of corporate interests, corruption, and inequality in any of the four states. Nevertheless, democratic backsliding poses a serious policy dilemma for the EU: confronting Poland and Hungary might push one or both out of the EU; but accommodating backsliding undermines the credibility of EU’s commitments to its own constitutional values, and might encourage others to follow the “illiberal” path. Yet taken together, the Visegrád Four suggest that it might not be easy for other EU member states to follow Hungary’s path. As Poland ran up against the EU’s limits, it saw the specter of a future choice between a return to liberal democracy or acceptance of relegation to a second-tier status in the EU, or even expulsion. Even more significantly, the Czech and Slovak cases show that it can be difficult for politicians that are even suspected of harboring “illiberal” plans to win elections. Even when they do, they face strong institutional constraints. Babiš and Fico are no Orbáns or Kaczyńskis, but even if they were, the illiberal path is strewn with more obstacles than was the case for Orbán in 2010. Orbán might have inspired imitators, but the defenders of liberal democracy have also learned their lessons.