In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, unemployment in the United States reached historic levels, with widespread economic insecurity persisting months after the pandemic’s onset. In June 2020, 32% of US adults reported not having $400 on hand for an emergency expense.Footnote 1 By August 2020, 57 million households, or nearly half the country, were reporting serious financial problems (RWJF, Health, and NPR 2020).Footnote 2 How does a major economic shock like the pandemic shutdown affect civic engagement, and can financial resilience mitigate crises’ negative impacts on participation? By analyzing census completion during the early months of the pandemic, this article sheds light on divergent participation trends: large income shocks correspond with decreased participation rates, but only when people lack access to economic safety nets such as government relief policies, unemployment benefits, or household savings.

US residents were asked to complete the decennial census just as national unemployment peaked in April 2020 at 23 million people (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2020): who responds to this constitutionally mandated census has lasting representational and resource consequences. Census completion is a particularly useful lens for understanding the relationship between economic insecurity and civic engagement. Filling out the census form is designed to be a civic act that requires minimal resources; requirements of time, financial cost, knowledge, and access are all streamlined to make participation as easy as possible. Nevertheless, one in four households did not complete the census in 2010, and rates were measurably lower in 2020. Even after a prolonged enumeration period during the pandemic, one in three households still had not completed the census as of September 2020Footnote 3. By minimizing obvious barriers to participation, the census enables an investigation of what additional factors may continue to depress civic engagement, particularly in times of crisis.

Past findings on the relationship between economic shocks and civic action have been mixed. From the standpoint of a resource model of civic engagement (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995), unemployment can increase available time, resources, and issue salience for participation, but it can also heighten financial stress and decrease mental resources available for civic action. I posit that economic shocks like unemployment have heterogeneous effects on civic action based on the availability of protective policies and sources of resilience that insulate from major financial fallout. Greater resilience increases the relative resources available for participation in times of crisis, so protective factors such as access to government relief, unemployment benefits, and savings should reduce any demobilizing effects of economic stress.

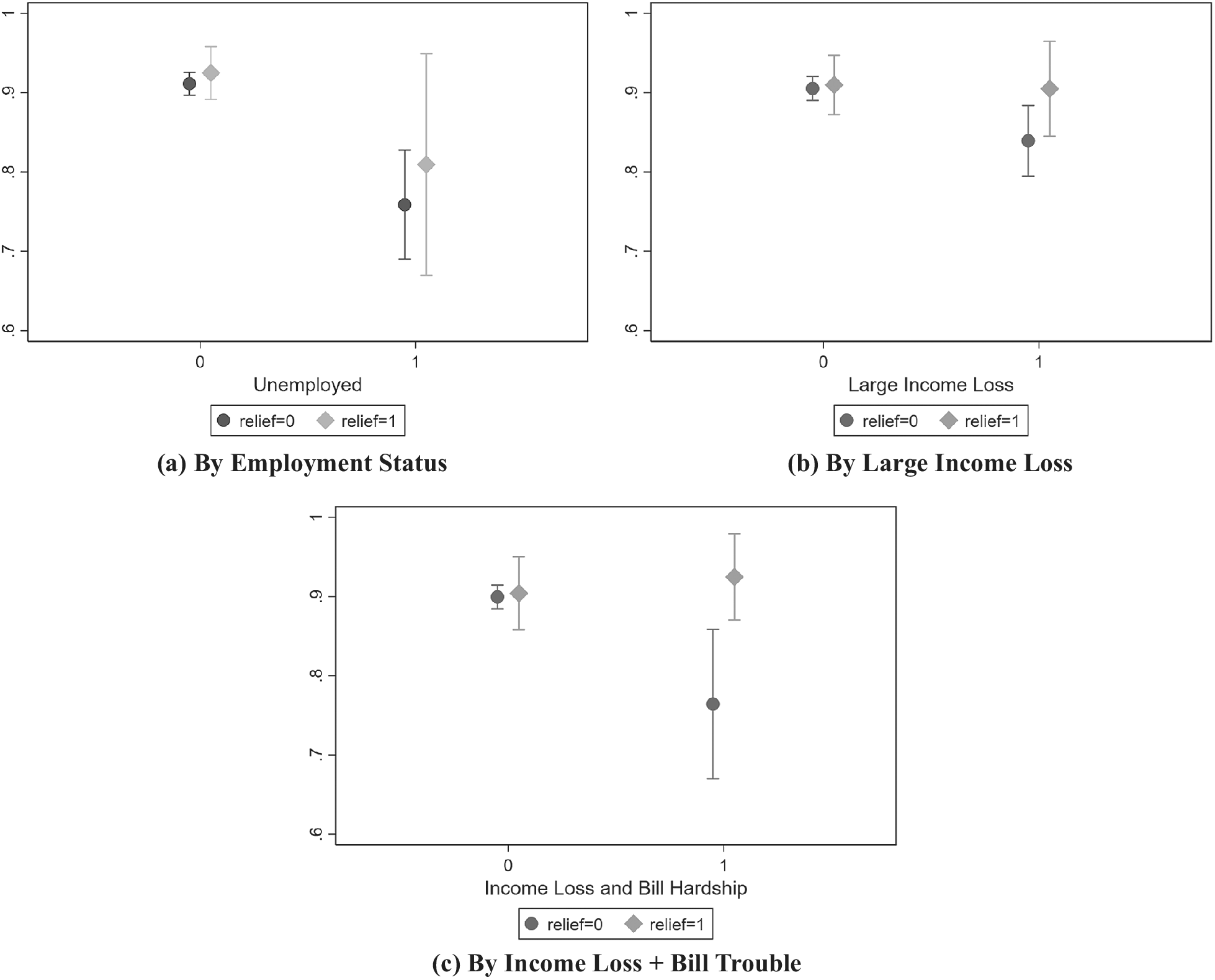

I test the relationship between pandemic-induced economic insecurity and civic action in two ways. First, I use an original national survey to show how economic shocks correlate with lower census completion rates at the individual level. I also show how this negative relationship disappears when individuals experiencing economic shocks have access to local government relief. For example, I find that for US residents most economically affected by the pandemic, the likelihood of having completed the census by June 2020 is 16 percentage points lower than for those who did not experience a large economic shock. Importantly, however, this decrease only exists when economically affected people lack access to state or local pandemic relief programs. For people who experience large economic shocks but who have access to relief policies, census completion rates resemble those of the rest of the population.

Second, I use Google Trends data on unemployment searches to model how higher attention to unemployment predicts lower census completion at the county level, controlling for 2010 completion rates. I find a significant interaction between high unemployment search rates and low financial resilience, as measured by low liquid assets and higher prevalence of service-sector jobs. In counties where unemployment searches are high, low resilience predicts substantially lower census completion rates.

These insights from the pandemic have a broad range of applications for scholars and policy makers. First, the disparities in census completion rates illustrate how acute shocks can contribute to longer and more entrenched cycles of inequality, both in political representation and resource allocation. Second, with high levels of economic insecurity even prior to the pandemic, millions of households are vulnerable to "mundane" crises such as unexpected large expenses, illness, and layoffs.Footnote 4This article lays the groundwork for understanding how these less visible shocks may still depress households’ civic engagement (with impacts on resources and representation) at a time when they arguably need to be most visible to government actors and institutions.

As a result, this article also fosters discussion of what structures may make political institutions accessible during times of crisis when resources (including mental bandwidth) for participation are limited. The pandemic highlights how a range of civic actions—including engagement of city councils, school boards, labor groups, state representatives, and more—can affect what resources are offered to communities in need, how those resources are distributed, and the quality of schools or the working environment experienced daily. The relationship observed here between economic shocks and civic actions like the census calls for deeper thinking about how to make more complex forms of participation accessible even to people experiencing high economic insecurity or acute crisis.

Finally, if economic shocks decrease civic engagement but resilience factors protect against such decreases, what can increase households’ resilience to future financial crises? This article looks at government relief programs, unemployment benefits, job protections, and household savings as sources of resilience. Their connection to positive civic engagement can serve as a springboard for broader discussion of what kinds of protective programs and policies are effective and along what metrics. The focus here on civic engagement suggests that financial resilience not only shapes how one weathers a crisis economically but also may produce a range of downstream behavioral outcomes for scholars to consider.

This article proceeds as follows. First, I provide theoretical motivation for the work. I then discuss heterogeneity in government shutdown policies and in those aimed at mitigating economic damage from the pandemic. Next, I present household- and county-level studies on census completion. I conclude with a discussion of implications for civic participation and representation in the wake of economic shocks.

Insecurity, Resilience, and Civic Engagement

Economic insecurity reflects the degree to which individuals are protected against hardship-causing economic losses (Hacker et al. Reference Hacker, Huber, Nichols, Rehm, Schlesinger, Valletta and Craig2014). It is a related but distinct concept from poverty, in that it measures how vulnerable one is to economic shocks or crisis, regardless of income level. Even before the pandemic-induced economic downturn, high levels of economic insecurity existed in the United States, rendering large numbers of households vulnerable to crisis. Studies from the pre-pandemic period consistently find that 30–40% of US households lacked $1,000 to cover an emergency expense (Hacker Reference Hacker2019; Lusardi et al. Reference Lusardi, Schneider, Tufano, Morse and Pence2011; Roll and Grinstein-Weiss Reference Roll and Grinstein-Weiss2020). In other words, before the pandemic shutdown, one in three US households was one crisis away from being unable to pay the bills, with this insecurity extending well into the middle class (Kaplan, Violante, and Weidner Reference Kaplan, Violante and Weidner2014).

Unemployment and underemployment from the coronavirus pandemic delivered an acute shock to millions of households, many of which were already economically insecure. The pandemic highlights the importance of understanding the relationship between economic shocks and political behavior, including the role that protective policies and other resilience factors play in buffering against negative impacts of a crisis. Here, I draw connections between existing work on economic shocks, resilience, and behavior to generate expectations for how the coronavirus pandemic would affect civic engagement.

Negative Economic Shocks and Resilience

In this article, I use the term economic shock to refer to a sudden income loss at the household level. Economic shocks have been linked to predictable, transient changes in political opinions, but insights into how shocks affect actual behavior have been more limited and less conclusive (Margalit Reference Margalit2019). The experience of unemployment has been shown to shift policy attitudes among the unemployed (Häusermann, Kurer, and Schwander Reference Häusermann, Kurer and Schwander2016; Wehl Reference Wehl2019), as well as among their social networks (Alt et al. Reference Alt, Jensen, Larreguy, Lassen and Marshall2021). In addition to changes in public opinion, research has shown mixed results on the relationship between economic shocks and political behavior. Some work finds that, at low socioeconomic levels, unem ployment corresponds with decreased perceived political efficacy (Scott and Acock Reference Scott and Acock1979) and political engagement (Hunter Reference Hunter2000; Lim and Sander Reference Lim and Sander2013). Individuals facing foreclosure are less likely to vote (Shah and Wichowsky 2019). However, other studies, particularly analyses of state-level unemployment data, find that unemployment is related to increased turnout and participation (Burden and Wichowsky Reference Burden and Wichowsky2014; Cebula Reference Cebula2017). Some work suggests that economic shocks demobilize through a mechanism of reduced trust, whereas other findings propose a linkage between blame attribution and behavior (Levin, Sinclair, and Alvarez Reference Levin, Sinclair and Alvarez2016). Unemployment also fosters withdrawal emotions that may decrease turnout (Aytaç, Rau, and Stokes Reference Aytaç, Rau and Stokes2020), particularly if the experience of unemployment also increases one’s risk of depression (Ojeda Reference Ojeda2015).

In times of crisis, structures at the household, workforce, and policy levels can promote resilience and buffer against negative impacts of an economic shock. Resilience at the household level comes from factors such as the size of one’s liquid assets or savings, access to credit, and social networks that have an ability to provide support during hard times (Hacker et al. Reference Hacker, Huber, Nichols, Rehm, Schlesinger, Valletta and Craig2014). At the workforce level, resilience is stronger where employee protections make sudden layoffs less likely, higher wages enable a higher savings rate, or laid-off workers receive severance compensation from employers. Government policies also can promote resilience by providing unemployment benefits or financial assistance to people experiencing economic shocks. For people with less resilience, economic shocks are more likely to have severe consequences. For example, where government policy offers limited insulation from economic shocks, households turn to debt to weather financial shortfalls (Wiedemann Reference Wiedemann2021a, Reference Wiedemann2021b). Furthermore, if social safety nets are weak and debt is high, people face greater risk that any future shock will result in their going into arrears or bankruptcy (Morduch and Schneider Reference Morduch and Schneider2017).

In terms of political behavior, the effects of greater financial support so far have been mixed. In the United States, minimum wage increases are linked to higher voter turnout among low-wage workers (Markovich and White Reference Markovich and White2019), but natural resource windfalls correlate with lower turnout, potentially due to contemporaneous declines in educational attainment and increased substance use (Sances and You Reference Sances and You2019). Although exogenous increases in unearned income are not linked to increased rates of voting among recipients, this same unearned income increases voting among the children of low-income recipients, suggesting that the benefits of resilience can accrue across generations (Akee et al. Reference Akee, Copeland, Holbein and Simeonova2020). In Spain, randomized financial support increases the likelihood of voting for incumbents but does not change the overall assessment of government (Bagues and Esteve-Volart Reference Bagues and Esteve-Volart2016). The Mexican conditional cash transfer program Progresa has had little or no effect on either turnout or incumbent vote (Imai, King, and Velasco Rivera Reference Imai, King and Rivera2020). Despite recent advances in research on the impacts of cash windfalls on political behavior, much remains unknown about how shocks and protective factors interact, particularly for political behaviors other than voting.

Economic Stress and Civic Engagement

How does an acute economic shock, particularly for low-resilience households, affect what resources are available for civic participation? The resource model of civic engagement considers how resources such as time, money, and knowledge predict political participation and helps explain gaps in participation by socioeconomic level (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995). Poverty increases both the opportunity costs of political participation and the number of daily tasks that compete with political issues for one’s attention (Rosenstone Reference Rosenstone1982). Recent work on the resource model of civic engagement has found that policies can increase participation by reducing participation costs (Braconnier, Dormagen, and Pons Reference Braconnier, Dormagen and Pons2017) and economic disparities (Baicker and Finkelstein Reference Baicker and Finkelstein2018).

In this article, I do not dispute that resources like time and money matter. Instead, I assert that even when conventional participation barriers like time and monetary cost are minimized, economic shocks still make participation relatively more costly for those affected the most by them. Low-barrier civic actions (such as census completion or voting by mail) still take time from other potentially urgent tasks like job hunting or working side jobs. Furthermore, I assert that economic shocks sap another necessary resource for participation: mental bandwidth.

Under stressful or crisis conditions, one’s attention is redirected to address the stressor, meaning that attention available for civic engagement decreases. Although research on economic insecurity or shocks is more limited, evidence shows that poverty elevates one’s cortisol level, a hormonal indicator of stress (Haushofer and Fehr Reference Haushofer and Fehr2014). Mental tasks such as memory, goal setting, and impulse control—all elements of cognitive function called “executive control”—are disrupted when stress is high (Kim and Diamond Reference Kim and Diamond2002; Shields, Sazma, and Yonelinas Reference Shields, Sazma and Yonelinas2016). This stress response occurs automatically; by increasing the mental bandwidth that one has available for addressing sources of stress, less bandwidth is available to process other incoming information (Brown, Gagnon, and Wagner Reference Brown, Gagnon and Wagner2020). In the case of poverty, the brain is forced to make trade-offs in finite cognitive bandwidth (Mani et al. Reference Mani, Mullanathain, Shafir and Zhao2013), resulting in more short-sighted behaviors that can undermine one’s long-term self-interest (Bickel et al. Reference Bickel, Wilson, Chen, Koffarnus and Franck2016; Shah, Mullainathan, and Shafir Reference Shah, Mullainathan and Shafir2012). Economic insecurity also is linked to behaviors indicative of higher cognitive load, and these effects remain for the economically insecure across socioeconomic levels (Weinstein and Stone Reference Weinstein and Stone2018). It also increases anxiety and risky behaviors; research in public health has found that food insecurity corresponds with lower impulse control (Nettle, Andrews, and Bateson Reference Nettle, Andrews and Bateson2017; Staudigel Reference Staudigel2016).

Much of the existing research on economic insecurity and politics has focused on income security’s effect on political opinion and policy support (Ballard-Rosa, Jensen, and Scheve Reference Ballard-Rosa, Jensen and Scheve2018; Hacker, Rehm, and Schlesinger Reference Hacker, Rehm and Schlesinger2013), such as changes in policy support when people in one’s social network experience insecurity (Newman Reference Newman2014). Work on insecurity in Brazil finds results similar to my expectations in the United States. Poverty and economic insecurity have different relationships with political action: it is insecurity—rather than absolute income level—that corresponds with decreased political engagement (Brooks Reference Brooks2014). A limited number of studies also have begun to test how stress leads to changes in political behavior. Randomly cueing people to think about stressful events correlates with decreased voter turnout (Hassell and Settle Reference Hassell and Settle2017). Thus, messages that have high issue salience may inadvertently demobilize their target audience by making them anxious (Levine Reference Levine2015). So far, the mechanism for these effects is untested.

Recent work on the resource model of civic engagement also suggests that well-designed support systems can temper negative impacts of stress on decision making and behavior. For example, although low socioeconomic status generally correlates with lower levels of protest, well-organized and visible vehicles for political action reduce socioeconomic disparities in participation (Kurer et al. Reference Kurer, Häuserman, Wuest and Enggist2019). This finding echoes research showing that, when people are experiencing stress, policies that streamline procedures and make information more accessible result in higher uptake and better performance (Mullainathan and Shafir Reference Mullainathan and Shafir2013).

Studying census completion rates enables an exploration of less overt ways in which shocks may further depress political participation, even when participation barriers are low. Completing the census is an example of civic engagement in which resources needed to participate are minimized, but where economic shocks would make action costlier for those affected in terms of available time and mental bandwidth. The census by design minimizes many of the conventional barriers to participation (time, cost, knowledge, and the like), and residents respond in minutes based on their preexisting knowledge, without needing to seek information about political issues or candidates. Census completion is even easier than voting by mail in most states: the forms arrive automatically, participation is either online or by mail, and postage is prepaid. Finally, census completion is mandatory; although usually not enforced, the law states that noncompliers can be fined (Legal Information Institute 2020).

Previous research on census participation has studied which demographics have higher completion rates (Couper, Singer, and Kulka Reference Couper, Singer and Kulka1998) and how the following may affect participation: questions perceived as sensitive (Baum et al. Reference Baum, Dietrich, Goldstein and Sen2019), the mode of completion (Dillman, West, and Clark Reference Dillman, West and Clark1994), and what kinds of messaging boost participation (Dillman et al. Reference Dillman, Singer, Clark and Treat1996; Trujillo and Paluck Reference Trujillo and Paluck2012). A significant opportunity exists to further understand how economic insecurity affects census completion rates.

I expect that if stress induced by economic shocks increases the amount of attention demanded by the crisis (in this case, the coronavirus pandemic and household economic impacts), less mental resources will be available to take action. Time will also be relatively more costly when one has an urgent need to replace lost wages. I expect this to be the case even when the opportunity for civic engagement is designed to be as easy and accessible as possible, as in the case of census completion.

It is possible that other mechanisms may be at work as well. People affected by economic shocks may become more politically disaffected or distrustful of government efficacy, which likely would decrease political engagement. Access to protective factors may not only insulate against financial hardship but would also help maintain faith in government efficacy. Additionally, from a practical perspective, economic insecurity can cause housing instability, and people with less permanent housing are more difficult to reach with political messaging or information that encourages engagement.

Although I do not directly test specific mechanisms, they motivate my observational expectation: economic shocks will correlate with lower civic engagement. However, as stressed by Hacker and colleagues (Reference Hacker, Huber, Nichols, Rehm, Schlesinger, Valletta and Craig2014) in their work on resilience, the presence or absence of protective factors can drive divergent outcomes in the aftermath of an economic shock. Consequently, I also expect that personal, professional, and policy factors that boost resilience will mitigate the adverse effects of economic shock on participation. Resilience in the form of greater economic resources (government support, job sector protections, liquid assets) will buffer against significant financial impacts from an economic shock, leaving one more likely to still have the time and mental resources needed for civic action.

My hypotheses, therefore, are twofold:

-

1. Civic action will be lower for people who experience large economic shocks, compared to similar people who do not experience a large shock.

-

2. In the presence of higher economic resilience, large economic shocks will not correlate with lower civic action.

The 2020 census provides an ideal opportunity to test these hypotheses. Its timing coincided with COVID-19’s initial spread in the United States and the commensurate economic shutdown. The official deadline for census completion was April 1, 2020, and physical census forms were sent to all unresponsive households during the second week of April.Footnote 5 Thus, the US government was requesting peak census engagement from residents just as millions of households were experiencing acute economic shocks.

At a time when the majority of households were working fewer hours or working from home, completing the census in theory should have been even easier than usual. However, based on existing evidence on how stress, particularly economic stress, affects behavior, it is likely that households experiencing high levels of economic hardship and stress during the pandemic would have been more likely to overlook census participation. These same households also may have felt less served by governmental institutions, and they may have been harder to reach at reliable addresses. Together, these factors predict that economic shocks would correspond with lower census completion rates.

Pandemic as an Economic Shock

Shelter-in-place policies were enacted by 45 states by April 8, 2020, affecting more than 96% of the US population.Footnote 6 Seasonally adjusted unemployment peaked in spring 2020 at 25 million residents (US Department of Labor 2020), with millions more experiencing reductions in hours or wages. Even though state and local jurisdictions began relaxing stay-at-home orders and business closures by late April, unemployment rates remained elevated; in August 2020, seasonally adjusted unemployment was still more than twice as high as pre-pandemic rates (8.4 versus 3.5%; see Bureau of Labor Statistics 2020).

Reduced hours, furloughs, and layoffs resulted in a sudden loss of income for millions of U.S. households. In June 2020 I conducted a nationally representative survey that found that 14.7% of adults were currently unemployed, and 20.5% had lost at least half their household income in April 2020, after accounting for unemployment and stimulus checks.Footnote 7 These findings are similar to other national surveys run at approximately the same time (see AP-NORC 2020).

However, not everyone experiencing unemployment saw large reductions in income, and others who remained nominally employed saw large wage reductions. In fact, only 6% of adults remained unemployed in June and thereby experienced a large income shock. By comparison, 14% of adults lost more than half their household income but remained employed, and another 8% of adults became unemployed without experiencing a large net loss of income. Differences in unemployment and lost income are due in part to variations in government policies, job sector, demographics, and random chance, all of which affected how large a net economic shock households experienced in spring 2020. Delays in federal stimulus funds, delayed or nonexistent unemployment benefits, and variations in state and local aid also affected the speed and size of economic relief. Job sectors such as the service industry experienced widespread layoffs, whereas sectors like food processing and grocery sales, which require similar skills and education, were considered essential. Overall, these variations in economic shock and resilience underscore the importance of exploring their relationship with civic action.

This article considers the bundle of programs and policies designed to blunt the impact of pandemic shocks, but that were not uniformly accessible; they include unemployment benefits, stimulus payments, moratoria on evictions and utility shutoffs, and deferment of rent/mortgage payments. At the federal level, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, passed in March 2020, offered two types of economic assistance. Economic Impact Payments (EIPs) provided a one-time stimulus of $1,200 for every adult and $500 for every child in the United States who met the eligibility criteria (IRS 2020), and people receiving unemployment benefits were eligible for an additional $600 per week for 39 weeks (through the end of July 2020). EIP relief, however, arrived unevenly due to logistics of delivering the payments, such as whether the IRS had recipients’ direct deposit information. By May 2020, 42.5% of households reported that they were still waiting for their stimulus checks, with low-income and nonwhite households disproportionately affected (Roll and Grinstein-Weiss Reference Roll and Grinstein-Weiss2020).

Whether one received timely unemployment benefits during the first months of the pandemic involved elements of randomness: delays affected 54% of households who applied. Outdated computer systems designed to detect fraud flagged for further action minor discrepancies such as a full middle name versus a middle initial (see Arnold Reference Arnold2020). Additionally, after the Great Recession, many states made it more difficult to apply for unemployment benefits as an alternative to raising taxes on businesses, and in April 2020 there were many reports from states such as Florida of long wait times and difficulty navigating online application portals. Nationally, only 14% of claims had been paid at the end of March and 47% by late April. Some states processed unemployment payments more slowly than others, with 32 states paying fewer than 50% of claims by late April (and some states paying fewer than 10% of claims; Stettner and Novello Reference Stettner and Novello2020). These delays also affected receipt of CARES Act unemployment payments. Delays in processing claims left millions of households without needed income during the early months of the pandemic (Stettner and Novello Reference Stettner and Novello2020).

To assess who experienced delayed unemployment benefits, I turned to the Understanding America Study (UAS), a tracking survey conducted by the University of Southern California that follows US attitudes and behaviors related to the coronavirus pandemic and was weighted to be nationally representative. I used UAS data from Wave 7, collected June 10–July 8, 2020, which surveyed 6,346 individuals and was the first wave to measure delays in unemployment benefits. For respondents or their spouses who applied for benefits, I coded whether the household had started receiving benefits or was still waiting. I excluded from the analysis applicants who were rejected because they were determined to be ineligible.

Education and second-generation immigrant status predict delays in receiving unemployment benefits; timely receipt of benefits do not correlate with other demographic characteristics (table 1, column 1). Here, college education may correlate with workforce sector or one’s facility in navigating the benefits application; country of family origin may correlate with job sector or names more likely to be flagged for minor spelling differences. These mixed results suggest that a combination of random and nonrandom factors resulted in the timely receipt of unemployment benefits.

TABLE 1 Delayed Unemployment Benefits and Economic Hardship

Notes: Column 1: logit model (odds ratios); likelihood receiving UI if unemployed; column 2: logit model (odds ratios); likelihood have $400 for emergency; column 3: OLS model; likelihood will run out of money in 3 months (100-pt scale); t statistics in parentheses. Robust standard errors clustered by state; population weights.

+ p < 0.10, ∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001

Importantly, delays in unemployment payments correlate with increased financial stress (table 1, columns 2–3). On a 100-point scale, households already receiving benefits reported being 9 points less likely to run out of money in the next three months, compared to those still waiting for benefits. Those waiting for benefits also were twice as likely to not have $400 on hand for an emergency expense.

State policy differences further contributed to variations in how much economic support households received during the pandemic shutdown. The size of some state unemployment payouts meant that, with the additional CARES Act payments, unemployment benefits replaced most of—or sometimes even more than—a household’s lost wages; other households felt larger reductions in income. Furthermore, some states provided additional benefits for residents not covered by existing policies; California, for example, provided undocumented residents up to $1,000 per household in pandemic assistance (CDSS 2020). Finally, variations in local policies led to further heterogeneity in the degree of economic crisis that households experienced during the pandemic. Local policies sometimes included provisions enabling deferment of rent or mortgage payments, as well as moratoria on evictions and utility shutoffs due to lack of payment.

Overall, although nearly one-quarter of the US workforce experienced layoffs in March and April 2020, financial impacts varied, as did households’ resilience in the face of economic shocks. Sources of resilience included both the household’s existing resources and the availability of policy protections. As this analysis shows, lower income households and households with delayed financial support suffered higher levels of economic stress and a greater sense of urgency to find additional resources in the shutdown’s aftermath. Households with more financial resources and those that received timely unemployment support were less likely to experience acute economic impacts.

These empirical data are supported by qualitative descriptions of US residents’ pandemic experiences, which I collected from 1,259 individuals across the country in April and May 2020.Footnote 8 Although respondents were recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk, participants—who skewed younger and lower income than the general population—in some ways were more typical of those affected most by the pandemic. Respondents were also more likely to be white and with higher education than a population-representative sample, meaning experiences of nonwhite and lower-education individuals were likely underrepresented (Levay, Freese, and Druckman Reference Levay, Freese and Druckman2016).

Even if the sample was a unique subset of the US population, the variation in the pandemic experiences described by respondents with different levels of net lost income brings further understanding to the trends observed in the UAS data. Respondents with no lost income described minimal economic problems; their responses did not indicate high levels of stress from the pandemic. Respondents who experienced reduced work hours but only small income shocks reported some stress and economic impacts; at the same time, they also mentioned factors that contribute to economic 13 resilience, such as receiving unemployment benefits, having a second income, or being able to live with family while unemployed. Finally, for those reporting large income shocks, the impacts they described—as well as their level of anxiety—were most pronounced. In this group, people frequently mentioned unemployment benefits that were insufficient or had not yet arrived, elevated stress levels, and income losses caused by work in the service sector. A random subset of responses from each subgroup is presented in the online appendix.

Household Economic Shocks and Relief Policies

Data and Methods

First, I explore the relationship between economic shocks, resilience, and census completion using an original YouGov survey of 2000 US adults. The survey was run during the first week of June 2020 and was weighted by region, gender, age, race, and education to be representative of the US adult population. The key outcome in this study is household census completion.Footnote 9

Respondents were asked a set of questions about pandemic-related economic shocks (see the online appendix), including whether their household had lost more than half their income in April 2020 and whether the household was behind on rent/mortgage and on bills for basic expenses (all compared to the same time in 2019). These data indicate that 20.5% of US households earned less than 50% of their normal income in April 2020, and 6% of households report significant financial hardship, saying they were behind on their rent/mortgage payments and bills for basic expenses. I use these metrics as measures of who in the population is experiencing a large economic shock as a result of the pandemic.

Additionally, YouGov provided data on employment status, which enabled identification of which respondents were unemployed; as stated earlier, 15% of respondents were listed as unemployed or temporarily laid off at the time of data collection. Although I expected that unemployment would show similar results whether or not it was caused by the pandemic, low pre-pandemic unemployment rates suggest that most participants listed as unemployed likely lost their jobs as a result of the pandemic.Footnote 10

In this study, I also moved beyond unemployment to investigate whether the availability of government policies, intended to mitigate economic impacts of a crisis, correlated with higher rates of civic engagement. To test this, I asked respondents whether their household was allowed to pause or reduce rent/mortgage payments during the pandemic.Footnote 11 This question was asked in the context of a federal moratorium on evictions, which initially was to last until September 2020 and was later extended. Some states and local jurisdictions offered stronger protections. The federal protection did not automatically apply to tenants; instead, tenants had to meet eight eligibility criteria and proactively provide their landlord with a signed declaration that they met these criteria. Although this order applied to an estimated 86% of renter households that earned less than $100,000, the burden was on the renter to declare eligibility to protection. In the absence of such declaration, evictions continued, with 43,526 filings by October 2020 in 17 cities being monitored (Benfer Reference Benfer2020).

Variation in state and local policies—and even whether the renter or homeowner’s dwelling had a federally backed mortgage—affected the availability of household protections. The patchwork of policies introduced significant variation in access to housing relief. Importantly, in many cases households had to have knowledge of these policies to proactively take advantage of their protections. My measure of housing relief captured the combined result of available local relief and its awareness, which I termed “access.”

In my survey, 24% of renters and 11% of homeowners said their household had access to payment relief. For households that lost more than half their income, reported rates of relief access rose to 26% for homeowners and 39% for renters. Because I did not have respondents’ location data, I could only measure self-reported knowledge of local relief policies. There is the possibility that ignorance of available housing relief might correlate both with economic shocks and civic engagement. I attempted to address this possibility in two ways. First, if the subgroup that did not report access to relief included people who had need and available relief but were unaware of it, this should dilute observed differences in census completion between the relief and nonrelief groups in my model.

In addition, variables that would raise concerns that reporting access to relief was driven by education, financial status, or political interest were not significantly correlated with the relief measure (table 2, column 1). Conversely, characteristics likely to correspond with the greater need of aid (person of color, renter) predicted substantially higher rates of relief knowledge. Importantly, these variables alone did not appear to predict census completion (see the online appendix table A4), helping reduce concerns of omitted variable bias in the subsequent analysis of census completion.

TABLE 2 Correlates of Reported Access to Housing Relief

Notes: Exponentiated coefficients; t statistics in parentheses; robust standard errors clustered by state.

+ p < 0.10, ∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001

I drew on Household Pulse Survey (HPS) data to further validate my measure of economic relief. The HPS is a Census Bureau product launched in response to the pandemic; I used Week 13 data, collected from August 19 to August 31, 2020, because it is the first wave to measure respondents’ use of stimulus funds to cover recent spending needs.Footnote 12 Federal, state, and local stimulus payments represent another policy that potentially insulates people from the pandemic’s economic shock. Using data from more than 62,000 respondents, I modeled how economic and demographic variables predict the likelihood of having used stimulus funds to cover expenses within the last week (online appendix table A1). I then used the coefficients and the same variables in the YouGov dataset to predict YouGov respondents’ likelihood of using stimulus funds.Footnote 13 Table 2, columns 2–3, shows that increased likelihood of using stimulus funds correlates strongly (in significance and magnitude) with reporting access to relief.Footnote 14 This suggests that people aware of relief programs were more in need of economic support.

YouGov respondents receive redeemable points for participation. Participation is often motivated by interest in the survey questions, and respondents often have higher political interest than the national average. Therefore, despite being nationally representative on key demographics, this sample in some ways represents a hard test for my hypotheses: given above-average political interest, we would expect census completion to be higher in this sample than for the national average and for completion rates to be less affected by economic shocks. Indeed, the reported census response rate of the sample is 87% in June 2020, compared to a contemporaneous national average under 60%. Even so, I still found significant interactions between economic shocks and insecurity, as described next.

Results

For this analysis I ran a series of logit models on the YouGov data assessing the relationship between economic shocks, access to economic relief (resilience), and census completion. Figure 1 presents main findings, and table A2 in the online appendix shows full models. Models control for observable characteristics that might correlate with access to or knowledge of housing relief policies: gender, age, education, income, race, ideology, political interest, renter status, and state. I operationalize economic shocks in three ways: respondent unemployment, a household income loss of 50% or more, and difficulty paying rent/mortgage plus a large income loss (considered indicative of a severe economic shock). Unemployment is the only key independent variable measured at the individual (not household) level. I expect this to underestimate observed differences by employment status, because households where other members were unemployed are still coded as employed if the respondent has a job. Otherwise, analysis is focused at the household level.Footnote 15

Figure 1 Predicted Probabilities of Census Completion, by COVID Impacts and Relief Policy

Note: The online appendix provides model coefficients (table A2) and number of respondents in each cell (table A3).

In a model without interaction terms, people experiencing unemployment are half as likely to complete the census as the employed, holding all else constant (significant at 99%). However, although current employment and higher income both predict higher likelihood of higher completion, the interaction effect is not significant. The relationship between access to housing relief and census completion becomes increasingly significant as economic shocks are more tightly operationalized. For people who lost over half their income, there is a significant difference in predicted probabilities of census completion for those who do and do not have access to housing relief (Figure 1b).Footnote 16

The difference in census completion between those with and without access to housing relief is even more pronounced when we look at those who experienced a significant economic shock: those who lost more than half their income and are behind on bills, including mortgage/rent (Figure 1c). This group is 14 points less likely to complete the census compared to respondents who did not experience a large shock. However, when this group has access to reduced or deferred payments, census completion is no different than the comparison group—a 16-point difference compared to those experiencing economic shock without access to housing relief.Footnote 17 In all three analyses, there is no statistically significant difference in census completion rates for the economically secure group between those with and without access to housing relief.

Although access to housing relief is correlated with observable characteristics such as race, age, and renter status, the nearly identical results for respondents with and without access to housing relief in the comparison group temper concerns that awareness of relief itself is driving results. If, for example, higher knowledge about relief policies and census completion both correlate with higher political interest, or if states with relief policies also have more effective census completion campaigns, we would expect those reporting access to housing relief to show elevated census response rates even when they did not have an economic crisis. Omitted variable bias may still come from factors correlated with housing relief, economic shock, and census completion, but such variables are less common. Bandwidth for processing new information in times of crisis is a possible example, because people under economic stress who do not or cannot access information about pandemic aid are also less likely to seek information about census completion. However, such an omitted variable would underscore an overarching theme of this article: that protective policies buffer against negative effects of shocks but only if people have access to them—and access requires both program availability and awareness. Under high stress, even small barriers can make access and engagement more difficult. Overall, results in figure 1 indicate that access to policies that protect households from the full brunt of economic shocks correlate with normal levels of civic engagement, but that economic shocks absent these protections correlate with lower civic action.

Vulnerability to County-Level Economic Shocks

Data and Methods

I now turn to county-level data to assess whether these household patterns in civic action are replicated at a national level. Do economic shocks correlate with lower census completion, and does greater resilience temper this relationship? For a nationwide analysis, unemployment offers a useful (albeit rough) proxy for measuring economic shocks; in the absence of financial resilience, it represents an unexpected and potentially large change in household well-being. However, it is difficult to obtain public data on unemployment with sufficient geographic granularity to be useful.Footnote 18

Therefore, to enable a more comprehensive analysis of unemployment shocks, I turn to Google Trends search data. Google Trends provide data on the relative popularity of search terms across time and geographic area.Footnote 19 Likely not everyone (or even a majority) who searched for “unemployment” was laid off. The search term more precisely measures topical interest, rather than the unemployment experience itself. However, national searches for “unemployment” increased 25-fold between early and late March 2020 as stay-at-home orders and widespread layoffs occurred; related terms such as "furlough" and "laid off" simultaneously showed similar but much smaller increases (see Figure 2; state-level trends are shown in the online appendix). Although this suggests that millions of people who did experience job cuts turned to Google for information, the measure has a high degree of noise that makes it more challenging to find significant results.

Figure 2 Trends in Google Search Terms, February 25 to June 6, 2020

Note: Google Trends daily data compiled and recalibrated to show search volume relative to the overall highest daily rate (100).

Google does not make trend data publicly available at the county level, but DMA (Nielson media market-level) data are available. For this study, I acquired DMA-level relative Google search rates for the term "unemployment" (rates averaged over March 25–April 25). There are approximately 200 DMAs in the United States, many of which cross state boundaries. I analyze my data at the county level, so all models include two-way clustering by DMA and state.

As in the household-level analysis, I operationalize both economic shock ("unemployment" searches) and two main county-level measures of resilience. First, I use the estimated percentage of households that are liquid asset poor (without sufficient liquid assets to subsist at the poverty level for three months without income). This metric is part of the Prosperity Now Scorecard and is calculated using data from the 2017 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households and the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) 2014 Panel, Wave 2. I expect counties to be more affected by economic shocks when fewer people have sufficient liquid assets to cover an emergency.

I also use prevalence of service-sector jobs, as reported in the 2018 American Community Survey (ACS), as a measure of one’s vulnerability to pandemic shocks. The service sector was disproportionately impacted by layoffs during the shutdown, and service-sector workers are often less financially resilient to shocks than the average worker due to fewer protections or benefits. For example, low-wage service jobs that depend on tips may have smaller unemployment benefits, and not all service workers are eligible for full unemployment benefits (workers in the gig economy, some noncitizens, and so on).

I also consider median household income as a rough measure of resilience. Here, I assume that higher earnings can provide greater resilience in the face of economic shocks: better access to credit, potentially higher savings, more financially stable social networks, and so on (Hacker Reference Hacker2019). However, with economic insecurity shown to extend into the middle class, income is limited in the ability to tightly identify resilience and thus is only used as a robustness check.

The dependent variable is the 2020 county census completion rate as of June 6, 2020.Footnote 20 The June 6 date corresponds with timing of household reminders sent in May, as well as the timeframe of my YouGov survey. To account for systematic differences in counties across time that may drive different completion rates, all models also include counties’ final 2010 completion rates. The difference between the 2020 completion data and 2010 final completion rates for every county is illustrated in the online appendix (figure A1).

My theory predicts that as attention captured by unemployment increases, counties with less economic resilience (fewer liquid assets, higher percentage of service-sector jobs, and lower median income) will show lower census completion rates, as compared to less vulnerable counties and counties with fewer unemployment searches. To control for other county-level factors, I use 2018 ACS 5-year estimates of variables including= gender, race, age, education, logged population, percent residents who are citizens (given concerns about citizenship questions biasing response rates), broadband access (since census completion was first available online), and greater housing tenure (since higher housing instability may increase difficulty in being reached by census officials).Footnote 21 I also include a six-point 2013 urban–rural scale developed by the CDC. All models include state fixed effects.

Results

First, it is illustrative to assess what factors predict census completion a decade ago in the absence of a national pandemic and economic shutdown. Similar to other forms of civic engagement (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995; Rosenstone Reference Rosenstone1982), we see that race and income correlate with 2010 census completion rates (table A4). Completion rates are higher when counties are wealthier, whiter, more populous, and have better internet connectivity. Counties that are older and more female also have higher completion rates. Perhaps less expected is that controlling for other factors, including prevalence of long-term residents, a higher percentage college graduates correlates with lower completion rates. Percentage of residents who are citizens is also marginally significant.

Recognizing these underlying differences in propensity to participate, how does economic insecurity predict census completion during the pandemic? Figure 3 illustrates predicted census completion rates in early June 2020 based on the interaction of unemployment searches and (a) low liquid assets and (b) the prevalence of service-sector jobs. The underlying models are presented in table 3, which also provides the interaction of unemployment and median household income as a robustness check.

Figure 3 Predicted Census Completion by Frequency of Unemployment Searches

Note: See table 3 for model coefficients.

TABLE 3 Census Completion (June 2020) by Unemployment Searches and Insecurity

Note: Two-way clustered standard errors by state and DMA; state fixed effects.

+ p < 0.10, ∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001

These results show support for my hypotheses. The interaction between high unemployment searches and measures of resilience correlates with lower census completion in June 2020. Similar trends exist when using alternative search terms ("furlough" and "laid off") or April census completion dates (see tables A5–7 in the online appendix for robustness checks). The models estimate that economically insecure counties with high unemployment searches have census response rates that are at least 15 points lower than other counties, controlling for 2010 response rates. While not causally identified, the results support my hypotheses.

Importantly, where unemployment searches are low, neither variations in assets nor percentage of service-sector jobs predict variation in the census completion gap. This suggests that insecurity alone is not predictive of reduced participation. Rather, it is in combination with economic shocks—or, at minimum, attention paid to economic shocks—that economic insecurity predicts decreased engagement.

Implications

When economic shocks occur, protective factors—be they personal, like higher income, or policies like unemployment benefits and housing relief—play a role in boosting the resilience of economically insecure households (Hacker et al. Reference Hacker, Huber, Nichols, Rehm, Schlesinger, Valletta and Craig2014). This article suggests that factors that buffer against economic shocks may also buffer against decreases in civic engagement. At the household and county levels, economic shocks interact with resilience factors to predict census completion. In the absence of financial safety nets, economic shocks correlate with lower census completion rates; however, census completion is higher with access to sources of resilience, such as pandemic relief, liquid assets, and job protections.

Although the data presented here do not enable testing of the causal mechanism, past research suggests that, by helping smooth or reduce economic shocks, resilience factors enable individuals to have more resources (time, money, or mental bandwidth) for civic engagement. When resilience translates into housing stability, information and mobilizing messages can reach people more easily. When receiving protective policies, individuals also may maintain a stronger trust in government institutions. In total, when resilience is higher, participation levels remain stable under shocks that otherwise correlate with disengagement.

It is worth noting that this article may underestimate the prevalence of longer-term consequences of the pandemic’s economic impacts. In my national survey conducted in early June 2020, I found that 6% of adults experienced a large income loss and were also behind on bills and rent. As unemployment benefits ended and eviction moratoria expired, more households were being exposed to the full force of under- or unemployment when deferred bills came due. Recent survey data support this assessment, showing that 43% of U.S. residents continue to be affected economically by the pandemic. Among those still affected, 75% expect to need at least 6–12 months to recover financially (AP-NORC 2021).

Beyond the pandemic’s immediate impacts, this article’s insights into civic engagement during times of crisis are relevant for at least four important streams of political science and policy knowledge. First, my finding that economic shocks and low financial resilience correlate with lower household- and county-level census completion means that short-term disparities in the pandemic’s economic toll may be codified into longer-term disparities. Even absent a national economic crisis, low income and economically insecure populations are less likely to complete the census (based on 2010 data). If the pandemic’s uneven economic impact drove further differences in census participation, the individuals and communities most affected by the pandemic in 2020 may be systematically undercounted in the census. Because the census count is used to determine political representation and allocation of federal resources for the next 10 years, short-term decreases in civic engagement during an acute economic shock may result in a decade of lower financial support and government responsiveness. These disadvantages may make the same individuals more vulnerable to further crises in the future, perpetuating cycles of unequal resources and representation.

Second, census completion is only one example of civic engagement, and pandemic layoffs are only one example of economic shock. Even absent a national crisis, millions of US households are one adverse event away from economic crisis. Prior to the pandemic, an estimated 30–40% of households in the United States reported not having $1,000 in savings for an emergency. An emergency medical expense, an unexpectedly large utility bill, property damage, a major car repair, one-time government fines or fees—although not capturing the news headlines as the pandemic did—commonly occurred in the privacy of homes across the country prior to the pandemic, and they will continue to occur after the pandemic has subsided. This article sheds light on how these less visible household-level crises may affect civic engagement broadly, both beyond census completion and the pandemic context. With high numbers of households living on the financial edge— including significant portions of the middle class—and high variability in household resilience given the limits of US social policy, there is great value in continuing to study how economic shocks affect civic action, and the role of resilience in mitigating disengagement.

Furthermore, economic insecurity is not a US-specific phenomenon. Compared to the United States, many countries in the global north have an even greater share of wealthy households living with little savings for emergencies. In countries like Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, and Spain, this wealthy "hand-to-mouth" sector of the population is larger than the countries’ poor populations similarly living on the financial edge (Kaplan, Violante, and Weidner Reference Kaplan, Violante and Weidner2014). Future research may explore how economic shocks interact with resilience in comparative contexts to affect the economically insecure, particularly given variations in countries’ social safety nets.

Third, this article demonstrates that economic shocks and limited resilience still correlate with lower participation rates, even when civic engagement requires few resources of political knowledge, time, and money. The pandemic illustrates how civic action is arguably more important for the economically insecure during times of crisis, given the potential benefits of additional government visibility and support. Beyond census completion, pandemic-era engagement with city and county officials had the potential to shape community priorities in distributing millions of dollars in CARES Act assistance to local governments. Primary and general elections determined representation from local to national levels. Debates among school boards, unions, and local political leaders shaped choices about remote or in-person learning, with heightened consequences for more vulnerable populations. Yet, at a time when civic engagement had the potential to shape resource distribution and health with direct impacts on the economically insecure, this article suggests that economic shocks from the pandemic may have made participation harder for those with the most at stake.

If time is relatively more costly for people experiencing crisis, and mental bandwidth for civic action is limited due to financial stressors, this presents the question of how to make civic engagement—from participation in local government to voting and advocacy—accessible even for people with limited resources and in times of crisis. For example, many states expanded access to voting by mail in the 2020 general election in light of pandemic health concerns. More than three in four voters were eligible to vote by mail in the 2020 general election, with record-setting turnout. Future research likely will show whether greater access to the ballot box helped close persistent socio-economic disparities in turnout rates (Bonica et al. Reference Bonica, Grumbach, Hill and Jefferson2020), exacerbated turnout differences by further mobilizing high-propensity voters (Berinsky Reference Berinsky2005; Enos and Fowler Reference Enos and Fowler2014) or left relative turnout levels mostly unchanged (Barber and Holbein Reference Barber and Holbein2020). However, as many states now move to scale back voting accessibility, a large question for researchers and policy makers is what initiatives will make political participation more inclusive for individuals facing acute crises, rather than more difficult, and why. Insights here from census completion rates and elsewhere from the voting literature can be applied to a broader range of civic activities, where the economically insecure have traditionally been underrepresented but where their interests are arguably even more salient (local governance, school boards, unions, tenant and homeowner groups, etc.).

Finally, this article considers the role of resilience in mitigating negative effects of economic shocks. Broad, ongoing research questions include these two: How do income savings programs, access to low-interest credit, and financially stable social networks affect downstream civic engagement at the household level? Are there wider political and representational impacts of stimulus plans, unemployment insurance, and job protections that have been overlooked thus far? My findings that greater resilience correlates with higher participation underscore the value of further research into sources of resilience and their consequences for civic engagement.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592721002024.

Acknowledgements

The author is sincerely grateful to four anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of the manuscript and detailed feedback. The project described in this article relies on data from survey(s) administered by the Understanding America Study (UAS), which is maintained by the Center for Economic and Social Research at the University of Southern California (USC). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of USC or UAS.